Kasaba R. The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 4, Turkey in the Modern World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

Fig. 16.9 Early examples of squatter houses (gecekondu) on the urban fringes of Ankara:

the legacy of massive migration from rural Anatolia to major cities starting in the 1950s

and continuing in the following decades

[photograph by the author]

lifestyles, consumer goods and middle-class wealth, all captured by the DP

slogan of ‘becoming Little America’. As miles of new roads and highways

were constructed (acquiring a status analogous to railways in the RPP era),

agriculture mechanised and cities expanded, Turkey rapidly became a classic

case for modernisation theories in social science, affirming the latter’s linear

models of development.

33

Although the DP was swept out of power by the 1960

military coup, the socio-economic transformations of the DP era continued

into the next two decades. Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the DP decade

is the phenomenal urbanisation unleashed by massive migration from rural

areas and the subsequent growth of squatter settlements around major cities,

Ankara and Istanbul in particular (see fig. 16.9). For the first time, masses

of people came in contact with the ambivalent experiences of modernity. As

large migrant populations encountered the seemingly endless possibilities,

lifestyles, aesthetic norms and high cultures of modern life in cities, they also

33 Especially D. Lerner, The Passing of Traditional Society (New York: Free Press, 1958)and

B. Lewis, The Emergence of Modern Turkey (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968).

444

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

began to be shaped by a profound awareness of their own exclusion from these

things, preparing the ground for successive social upheavals.

The 1950s marked a conspicuous departure from the cultural politics of the

early Republican period. The switch from

´

etatist to more liberal economic

policies was reflected in the cultural scene by an accompanying shift from

state to private sponsorship of arts and architecture. Private clients, especially

banks, businesses and corporations, began to emerge as the primary patrons

sponsoring art exhibitions, organising architectural competitions and com-

missioning artists and architects. While the art galleries of banks and foreign

cultural missions played a pioneering role in the early 1950s, the proliferation

of private galleries had to wait until the 1970s. Nonetheless, this period saw

the gradual development of an art market in Turkey in the capitalist sense, in

stark contrast to the ideologically motivated state art exhibitions of the early

Republican period. As art education dispersed beyond the traditional confines

of the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul and the Gazi Teachers’ College in

Ankara into various fine arts departments of new universities, cutting-edge

artistic developments began happening outside these institutions altogether,

in rapidly multiplying private studios. Many art historians and critics observe

that the individuality of the artist emerged as a major force in this period, in

contrast to the predominance of groups or schools in the early Republican

period.

34

The disintegration of Group D at the same time that the painter Nuri

˙

Iyem opened the first individual art show in 1946 is symbolic in this respect.

Like in many other countries after the Second World War, a pervasive

‘Americanism’ can be observed in the Turkish architectural scene of the 1950s,

especially after the construction of the canonic Istanbul Hilton hotel in 1952–5

(see fig. 16.10). Widely published in international architectural magazines of

the time and designed by the US corporate firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merril

(with Sedad Hakkı Eldem as the local collaborating architect in Turkey), the

Istanbul Hilton best represents the aesthetic and ideological shifts of the post-

Second World War era. As Annabel Wharton and others have observed, to

enter the Hilton was to gain admission to ‘a little America’,

35

the paradigm of

the benevolent and democratic capitalist society that the DP regime embraced

as model. In Turkey as elsewhere, the 1950s ushered in a corporate ‘interna-

tional style’ in the form of steel-frame high-rises, glazed curtain-walls and

an abstract fac¸ade aesthetic of repeating modules expressive of high modern

efficiency. Largely derived from the work of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and

34 Renda, ‘Modern trends in Turkish painting’, p. 240.

35 A.Wharton, Building the Cold War: Hilton International Hotels and Modern Architecture

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), p. 22.

445

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

Fig. 16.10 Istanbul Hilton Hotel (1952–55), designed by the US corporate firm Skidmore,

Owings & Merril with Sedad Hakkı Eldem as the local collaborating architect

[courtesy of the late Sedad Hakkı Eldem; Aga Khan Programme, MIT]

his disciples in the US (such as his canonic Seagram Building in New York,

1954–8), this style epitomises the rise of the US as a world power after the Sec-

ond World War. The Emek office tower, the so-called ‘skyscraper’ (g

¨

okdelen)

in Ankara (1959–64) designed by Enver Tokay, is one of the first examples of

such steel-frame, curtain-wall high-rises in Turkey. Equally influential upon

the architectural scene in Turkey were the later works of Le Corbusier (such as

his Unit

´

e d’Habitation in Marseille, 1948), as well as the Le Corbusier-inspired

‘tropical modernism’ of Latin American and Caribbean architects (such as the

work of Oscar Niemeyer in Brazil), all of which were published extensively in

Turkish architectural journals. Following the Istanbul Hilton, other significant

projects such as the Istanbul City Hall (1953) by Nevzat Erol, the Anadolu Club

on B

¨

uy

¨

ukada (1959) by Turgut Cansever and Abdurrahman Hancı and the

Lawyers’ Cooperative Apartments in Mecidiyekoy, Istanbul (1960) by Haluk

Baysal and Melih Birsel represent the best and most sophisticated syntheses of

these multiple international influences.

36

36 See S. Bozdo

˘

gan, ‘Democracy, development and the Americanization of Turkish archi-

tectural culture in the 1950s’, in S. Isenstadt and K. Rizvi (eds.), Modernism and the Middle

East (Seattle: University of Washington Press, forthcoming).

446

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

Fig. 16.11 Turkish Pavilion at the Brussels International Expo (1958) designed by Utarit

˙

Izgi, Muhlis T

¨

urkmen, Hamdi S¸ensoy and

˙

Ilhan T

¨

ureg

¨

un, dismantled after the Expo

[courtesy of Burhan Do

˘

ganc¸ay]

In 1958, Turkey participated in the Brussels International Exposition (Expo

’58) with an elegantly designed modern pavilion that earned the country sub-

stantial praise within international architectural media (see fig. 16.11).

37

Con-

ceived as a showcase of Turkey’s newfound confidence as a NATO ally in the

Cold War context, as well as its artistic/architectural commitment to new

international trends in post-Second World War modernism, it was designed

by Utarit

˙

Izgi (1920–2003) and his three colleagues Muhlis T

¨

urkmen, Hamdi

S¸ensoy and

˙

Ilhan T

¨

ureg

¨

un, with the collaboration of Bedri Rahmi Ey

¨

ubo

˘

glu,

a former member of Group D and Turkey’s most prominent modern painter

and mural artist. The two main components of the design, the transparent

glass box of the main exhibition space and the smaller teak-wood and glass box

of the restaurant/caf

´

e, a modern reinterpretation of the traditional ‘Turkish

37 On the story of this pavilion see S. Bozdo

˘

gan, ‘Paradigme de la modernit

´

eturqueen

Europe: le pavillon turc’, in M. DeKoonig and R. Devos (eds.), L’architecture moderne

`

a

l’Expo ’58 (Brussels: Dexia/Mercatorfonds, 2006).

447

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

house’, were connected by a 50-metre wall covered by the colourful abstract

mosaics of Bedri Rahmi Ey

¨

ubo

˘

glu featuring stylised motifs from Anatolian

landscape and folklore. The incorporation of the latter as a defining ele-

ment of the main design concept was a superb example of ‘the synthesis

of the arts’ – a distinctly 1950s idea of collaboration between architecture and

the plastic arts ‘for the mutual benefit of both’, as Utarit

˙

Izgi explained it.

38

The incorporation of paintings, mosaic murals and abstract sculpture into

architecture was already a well-established trend in modern culture generally,

especially in Latin American modernism with results that captured the imagi-

nation of Turkish architects and artists through the 1960s. That the demount-

able modular components of the pavilion, including the mosaic panels of

Ey

¨

ubo

˘

glu, were brought back to Istanbul after Expo ’58 only to be abandoned

to neglect, oblivion and eventual loss is one of the tragic episodes in Turkish

modernism.

Another such unfortunate episode involves the distinctly modernist

Kocatepe Mosque project of Vedat Dalokay (1960) which, if built, could have

been the paradigmatic architectural monument of the DP years, when a new

reconciliation with Islam occurred. A conspicuous relaxation of the radical

secularism of the early Republic provided a favourable context for reintro-

ducing mosque design as an important architectural problem worthy of pro-

fessional attention. Dalokay’s design innovatively reinterpreted the central-

domed classical Ottoman mosque typology, using the cutting-edge technol-

ogy of a thin-shell concrete roof structure. Although the foundations were laid

out in 1963, the design remained controversial. The construction was halted

and the project shelved officially as a result of technical and programmatic

difficulties. The more plausible explanation, however, is the perennial tension

between secularists and Islamists in Turkey, the latter longing for the aesthetic

and formal symbols of traditional Islam, not its modernised versions. Over

the next two decades (1967–87), a very different Kocatepe Mosque was built

on the same site, in the form of a stone and marble-faced replica of a classical

Ottoman mosque, testifying to the strong symbolic charge of mosque design

in a country that still does not seem to have fully come to terms with secular

modernity.

While regaining the importance it had lost to Ankara during the early

Republic, Istanbul experienced the most dramatic and comprehensive mod-

ern urban transformations in this period. The extensive demolitions and new

construction carried out in the 1950s were conceived as a major project of

38 Utarit

˙

Izgi, Mimarlıkta s

¨

urec¸: kavramlar, ilis¸kiler (Istanbul: Yapı End

¨

ustri Merkezi, 1999).

448

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

Fig. 16.12 Prime Minister Adnan Menderes reviewing the model for the Golden Horn

Bridge, 1957; architect Sedad Hakkı Eldem to his left and mayor Fahrettin Kerim G

¨

okay to

Eldem’s left

[courtesy of the late Sedad Hakkı Eldem]

political legitimacy and public relations under the personal directive of Prime

Minister Adnan Menderes (see fig. 16.12). The wide Vatan and Millet Avenues

cutting through the old fabric of the historical peninsula and the shore road

along Marmara Sea connecting the tip of the historical peninsula to the airport

in the west still bear the legacy of Menderes’s ambitious urban interventions

(see fig. 16.13). Equally significant in terms of its consequences for Istanbul’s

urban fabric was the introduction of a new and soon-to-be-pervasive architec-

tural typology: the high-rise slab-block apartment, which was initially used for

cooperative housing schemes financed by credit from the newly established

Emlak Bank. Among the first examples are the Levent and Atak

¨

oy housing

schemes, which resolved issues of site planning, rational unit design and con-

struction quality with relative success. However, with the exception of a hand-

ful of such well-designed housing projects, mostly for the middle and upper

classes, most apartment blocks built in Istanbul and other Turkish cities in the

following decades were lesser examples, replacing aesthetic concerns with the

priorities and profit motives of the developer in a lucrative housing market.

Especiallyafter the landmark ‘condominium legislation’(KatM

¨

ulkiyetiKanunu)

of 1965 (which allowed ownership of individual units or flats within a multi-

unit apartment building), the early modern residential fabric of most cities was

rapidly torn down and replaced by newer, higher, developer-built multi-unit

449

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

Fig. 16.13 Demolitions and urban modernisation in Istanbul in the 1950s

[courtesy of

˙

Ipek Akpınar and Ara G

¨

uler]

apartments, turning the dwelling unit into a commodity – a financial asset

and a source of revenue. The speculative apartment boom of the next few

decades became the notorious symbol of the sterility, banality and repetitive-

ness of modern architecture and urbanism, turning major Turkish cities into

‘concrete jungles’, as it is often put in common parlance.

As in architecture, a closer look at the artistic production of 1950–80 reveals

an increased awareness of international artistic trends after the opening of the

country to the outside world. Aided by new ties with the US and post-war

Europe, Turkish painters and sculptors closely followed American abstract

expressionism, as well as surrealist, fantastic, pop art and other emerging

trends, producing artwork ranging from the merely derivative to the highly

original. In fact, Turkey itself was no longer the exclusive location of modern

Turkish art. Some of the best work was produced by Turkish artists living and

working abroad, such as Fikret Mualla (1904–69) and Abidin Dino (1913–93)in

Paris, the traditional art capital of the world, and Burhan Do

˘

ganc¸ay (b. 1925),

and Erol Akyavas¸(1932–99) in New York, the new centre of the art world after

the Second World War. Most importantly, these expatriate artists were no

longer sent abroad by the state to learn the latest techniques and bring them

back for application to national themes. They were often self-exiled artists

450

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

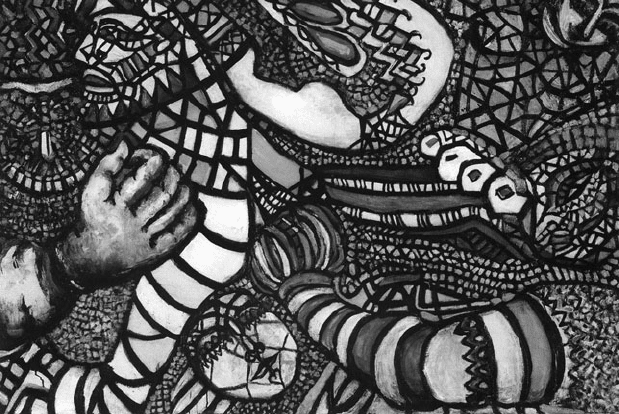

Fig. 16.14 Fahrelnissa Zeid, Soyuta kars¸ı m

¨

ucadele, oil on canvas, 1947

[Eczacıbas¸ı Collection, Istanbul Modern, Istanbul]

contributing to an international artistic culture, a culture that transcended

national boundaries and cultural codes. This does not mean, however, that

they left behind all native inspirations and home influences. Most of them

continued to carry the aesthetic inspiration of folk and popular arts as well

as of Islamic calligraphy and two-dimensional miniature paintings into their

modern abstract compositions, as, for example, in the work of Fahrelnissa

Zeid (1901–91), an accomplished female artist whose unique and fascinating

life spanned big Western metropolises such as Paris, London and Berlin as

well as traditional centres of Islamic art such as Istanbul and Baghdad (see

fig. 16.14).

The first important abstract paintings in modern Turkish art were produced

in this period by artists like Zeid, as well as her son Nejad Devrim (1923–95)

and others such as Mubin Orhon (1924–81), Selim Turan (1915–94) and Hakkı

Anlı (1906–91). While the works of these pioneers are of historical significance,

abstract artistic trends flourished in Turkey after the 1950s, with the work of

younger painters such as Adnan C¸ oker (b. 1927) and Adnan Turanı (b. 1925), and

sculptors such as

˙

Ilhan Koman (1921–86) and Kuzgun Acar (1928–76). Yet, as

many art historians/critics observe, the primacy of figurative approaches was

451

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

never fully shaken in Turkey, even in the heyday of abstract trends.

39

Some

artists tried abstract compositions in the 1950s, only to return to figurative

compositions in the 1960s. Others produced highly original work by which they

defied any sharp binary opposition between abstract and figurative painting.

The expressive brush-strokes of Omer Uluc¸(b.1931), the figure-ground plays

in the paintings of Orhan Peker (1927–78) and the abstract rhythmic patterns

of floating birds, autumn leaves or cityscapes of Devrim Erbil (b. 1937) stand

out, among others.

Among the more eccentric and original of contemporary Turkish artists

of this period, Y

¨

uksel Arslan (b. 1933) and Mehmet G

¨

ulery

¨

uz (b. 1938) made

distinguished reputations for themselves outside Turkey, especially with their

unique styles in illustrations and line drawings. Trained in Paris in the 1970s

and also involved with theatre and stage design, Mehmet G

¨

ulery

¨

uz is a prolific

illustrator of metamorphosing figures and ink sketches of half-human, half-

animal creatures bordering on the grotesque, as can be seen in his highly

acclaimed later work in New York. Y

¨

uksel Arslan’s work embodies an intense

intellectual content informed by philosophers and books as well as fantastic

and erotic imagery, and was enthusiastically received by Andr

´

e Breton and

the surrealists in Paris, where he exhibited his work in 1961. The paintings of

Cihat Burak (1915–94) and Erol Akyavas¸(1932–99), both of whom trained as

architects, also contained surrealist overtones and dreamy and metaphysical

collapsing of spaces. Yet, rather than arising out of the artist’s inner psyche,

desires and fears as surrealist art was defined in the West, their works were

intimately connected to their own cultural context. Cihat Burak’s fantastic

images of urban life and urban landscapes, for example, were informed by

his familiarity with and passion for Istanbul. The surrealist feeling of Erol

Akyavas¸’s earlier compositions, on the other hand, gradually gave way to his

later creative engagement with Islamic arts, especially after 1980. Likewise,

another highly accomplished artist, Burhan Do

˘

ganc¸ay (b. 1925), first painted

the walls, graffiti and posters of New York, gradually moving towards abstract

compositions inspired by torn strips of paper peeling away from walls, but also

alluding to calligraphic script.

After the military coup of 1960 brought ‘the DP decade’ to an end, democ-

racy was restored in 1961 with a relatively liberal constitution, after which the

Turkish political and cultural scene displayed a plurality of ideas, programmes,

political parties, popular tastes and artistic/architectural styles. A very impor-

tant feature of this period was the emergence of the Turkish left as a major

39 Tans¸u

˘

g, Ca

˘

gdas¸T

¨

urk sanatı,p.268.

452

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

force in politics, society and culture and the proliferation of socialist views,

especially among students, intellectuals and professionals, until their eventual

suppression by the military coups of 1971 and 1980. Unsurprisingly, a number

of Turkish artists also sympathised with the left and adopted versions of Social

Realism in this period. Following the earlier work of Nes¸et G

¨

unal (b. 1923)

in this genre,

˙

Ibrahim Balaban (b. 1921) painted poor peasants, bare-footed

children, toiling workers and farmers with big hands and sun-baked faces,

attracting the personal acclaim of Mehmet Ali Aybar, the leader of the newly

established Turkish Workers’ Party. At the same time, a highly politicised

Chamber of Architects and left-leaning architectural students became active

in questioning the role of the architectural profession and its relationship to

society at large.

After 1960, following developments in international architectural culture,

modern Turkish architecture entered a pluralist period, with a range of new

experiments highly critical of the legacy of the 1950s and of the formal vocab-

ulary and prevailing canons of international style. Once again the examples

of American architects, especially the ‘organicism’ of Frank Lloyd Wright,

the ‘new monumentality’ ideas of Jose Louis Sert and Louis Kahn and the

New Brutalism of Louis Kahn and Paul Rudolph, were the primary inspira-

tions for the Turkish architectural production of the 1960s and 1970s. Organic

forms and modular systems were employed to fragment the prismatic boxy

aesthetic of high modernism. The ‘brutalist’ aesthetic of exposed concrete,

brick or wood offered textured surfaces to replace the slick fac¸ades of glass,

metal and polished materials. The architectural school of Middle East Tech-

nical University (1962–3), designed by Altu

˘

g and Behruz C¸ inici (b. 1932), is a

well-crafted example of these trends, as is the work of S¸evki Vanlı (b. 1926),

who established a prolific practice in Ankara along similar precepts. The estab-

lishment of Middle East Technical University (METU) in Ankara was itself a

new challenge to the traditional hegemony of the Academy of Fine Arts and

Istanbul Technical University in the education of Turkish architects. Unlike

the French and German systems upon which the latter were originally based,

METU’s curriculum was modelled on American examples, with Louis Kahn’s

University of Pennsylvania directly involved in its foundation.

40

Most conspicuously, the early Republican quest for a ‘national style’ in archi-

tecture was abandoned in this period. The word ‘nationalism’ was replaced

with ‘regionalism’, as the marker of architects’ desire to ground modern archi-

tecture in a local context, sensitive to the topography, materials, climate and

40 A. Payaslıo

˘

glu, Barakadan kampusa 1954–1964 (Ankara: METU Publications, 1996).

453