Kasaba R. The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 4, Turkey in the Modern World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

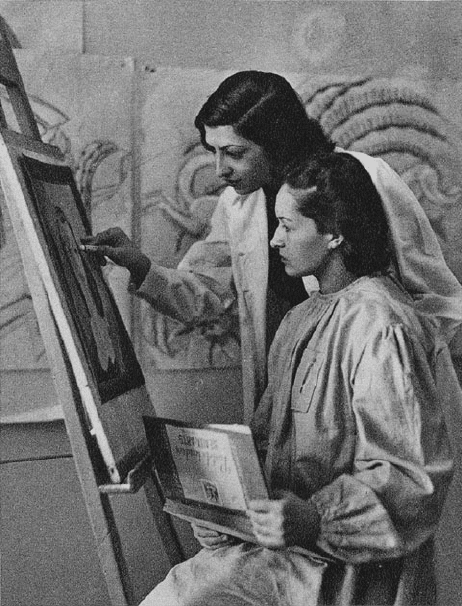

Fig. 16.3 Women artists, photograph from La Turquie Kemaliste 29 (February 1939)

[postcard from the author’s collection]

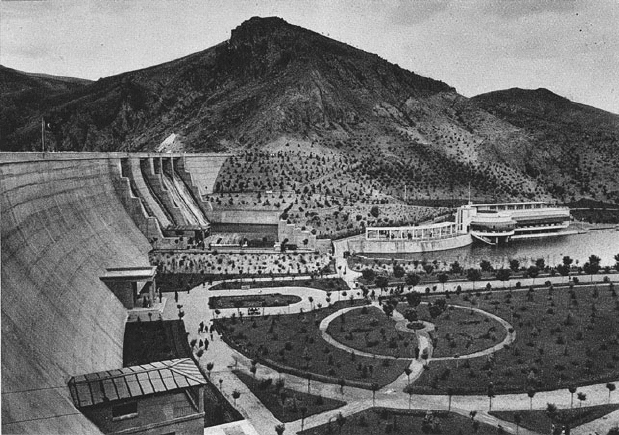

in the mid-1930s: the C¸ ubuk dam, the large urban park and artificial lake of the

‘Youth Park’ (Genc¸lik Parkı) and the Atat

¨

urk Model Farm and Forest (Atat

¨

urk

Orman C¸ iftli

˘

gi), collectively aiming at not only the ‘greening’ and beautifica-

tion of the city against the adversities of a barren land and an arid climate,

but also providing secular public spaces where the norms of ‘civilised’ public

behaviour and recreation could be displayed (see fig. 16.4). Beyond Ankara, the

construction of railway stations, schools and factories (including such Repub-

lican icons as the S

¨

umerbank factory towns in Kayseri and Nazilli) were the

most significant architectural extensions of the Kemalist project of modernity

into Anatolia.

The construction of Ankara as a modern capital out of the roots of an

insignificant Anatolian town is itself an episode of epic proportions, achieved

434

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

Fig. 16.4 C¸ ubuk Dam, public park and restaurant outside Ankara (1930–6)

[postcard from the author’s collection]

largely through the work of German, Swiss and Austrian architects and

planners who introduced modernism to Turkey under the rubric of ‘New

Architecture’. Of these, Swiss architect Ernst Egli and the German-Jewish

Bruno Taut were particularly influential as teachers at the Academy and as

the designers of major higher education buildings in 1930s Ankara, such as the

canonic

˙

Ismet Pas¸a Girls’ Institute (1930) and the Faculty of Humanities (1937)

respectively. A third major figure, the Austrian architect Clemenz Holzmeis-

ter, designed the entire governmental complex and the presidential residence

(1930–2) in the austere, official modernism known as ‘the Ankara Cubic’. It is

important to note that these German-speaking architects proposed the Ankara

Cubic not as an imported European modernism, but as a regionalist discourse

responsive to the climate, terrain and local materials of central Anatolia. They

were more ‘conservative’ in their work and discourse than the young Turkish

architects who internalised all the aesthetic and constructional canons of the

European Modern Movement, especially asymmetrical compositions of cubic

volumes with horizontal and vertical elements, unadorned surfaces, horizon-

tal band windows, continuous sills, cantilevering balconies, round corners

and, in many cases, flat roofs even when it was not technically possible to

435

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

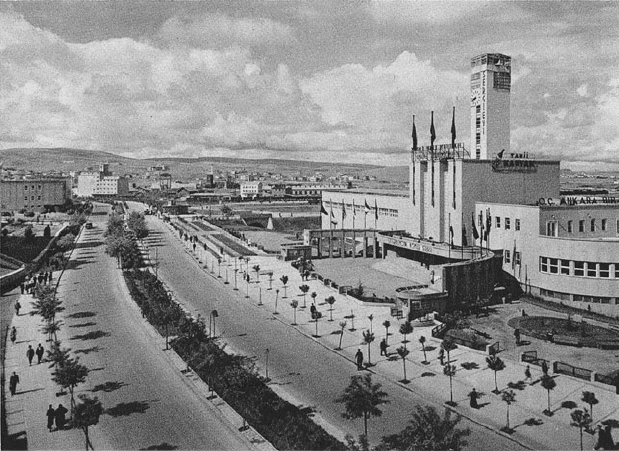

Fig. 16.5 The building of Ankara as the new capital city with the new Exhibition Hall

(Sergievi) designed by S¸evki Balmumcu to the right (1933)

[postcard from the author’s collection]

properly insulate them. Although Turkish architects had little access to major

state commissions in this period, exceptional accomplishments such as the

Ankara Exhibition Hall (1931–3)byS¸evki Balmumcu (see fig. 16.5) or the Min-

istry of Foreign Affairs residence (1933–4) by Seyfettin Arkan testify to a rapidly

maturing Turkish modernism.

After the 1926 modernist curricular reforms in the Academy, the archi-

tectural section graduated an entire generation of modernist Turkish archi-

tects who became active in professional organisations. Gathered around the

Fine Arts Association in Istanbul, they started publishing their professional

journal Mimar in 1931, renaming it Arkitekt three years later.

21

The writings

and projects published in this journal became the primary venues for pro-

moting the universalism and scientific claims of the Modern Movement and

its defining principles of rationalism and functionalism. In the absence of

21 Two more architectural journals started publication in the early Republican period: Yapı

in Istanbul after 1941;andMimarlık, the journal of the Turkish Society of Architects

(later the Chamber of Turkish Architects) in Ankara after 1944. See G. B. Nalbanto

˘

glu,

‘The Professionalisation of the Ottoman/Turkish architect’, Ph.D. thesis, University of

California (1989), pp. 150–7.

436

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

major public commissions (which typically went to the foreign architects),

young Turkish modernists such as Zeki Sayar, Abidin Mortas¸, Seyfettin Arkan

and Behc¸et

¨

Unsal turned their attention to residential architecture (mesken

mimarisi), designing the canonic ‘cubic’ villas and apartments of the 1930s with

their flat roofs and unadorned volumetric compositions. However, given the

poor state of the building industry, the formidable costs of reinforced con-

crete construction, shortages of skilled workmanship and the absence of any

large-scale low-cost, rationalised and industrialised housing production, these

modernist experiments remained limited to a handful of well-crafted individ-

ual houses for the Republican elite. The question of mass housing, one of the

central preoccupations of interwar modernism in Europe, did not become a

major item on the Turkish architectural agenda until after the Second World

War.

In art, the paradigmatic Group D, the closest movement in spirit to the

modernist avant-garde in Europe, was formed in 1932 and the journal Ar started

its publication as the group’smajor voice.Among the founding members of the

group were painter, art critic and group spokesman Nurullah Berk (1904–82),

other painters such as Cemal Tollu (1899–68), Bedri Rahmi Ey

¨

ubo

˘

glu (1913–

75), Sabri Berkel (1907–93), Zaki Faik

˙

Izer (1905–88) and Abidin Dino (1913–93),

and the sculptor Z

¨

uht

¨

uM

¨

urido

˘

glu (1906–92). Influenced by Andre Lhote and

Fernand Leger in Paris, the artistic premise of Group D was a critique of

Impressionism and the introduction of Cubist and Constructivist currents to

Turkish art. However, it is debatable to what extent Group D constitutes an

‘avant-garde’. The idea of a modernist avant-garde, as it historically emerged in

Europe in the 1910s and 1920s as a radical and subversive challenge to established

artistic norms, was, by definition, outside official ideology. It was an exaltation

of individual creativity, not of the collective; an exploration of the abstract and

universal, not of the figurative and the local. Group D, on the other hand, was

a product of the Kemalist period, when art was expected to have a larger social

function, and national idealism above and beyond individualistic experiments.

Like most artists and architects of the 1930s, Group D members also aligned

themselves with the RPP programme and contributed paintings to the

˙

Inkılap

Exhibitions organised by the state.

After 1935, Burhan Toprak succeeded the late Namık

˙

Ismail as the head of

the Academy of Fine Arts and a new set of appointments were made, marking

the predominance of European educators. More than two hundred foreign

artists and experts fleeing from the Nazi rise to power in Germany and Aus-

tria were invited to Turkey in this period, most of them playing key roles in

the establishment of Turkish higher education, both in the arts and in almost

437

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

every field of the sciences and the humanities. The painting section of the

Academy was given over to Leopold Levy with some Group D members as

his assistants. Bruno Taut replaced Ernst Egli as the head of the architectural

section, and the sculpture section was entrusted to Rudolph Belling, both

Taut and Belling having formerly worked in the radical Arbeitrats f

¨

ur Kunst in

Weimar Germany prior to the Nazi takeover of the arts. In the same years, the

architectural curriculum of the School of Engineering also underwent mod-

ernist reforms under the leadership of the Swiss-educated Turkish architect

Emin Onat (1908–61). Two other prominent architects of the early Republic,

the Austrian Clemenz Holzmeister and the German Paul Bonatz, also taught

in the School of Engineering, which was transformed into Istanbul Technical

University in 1944.

While the majority of the foreignprofessors teaching and working in Turkey

were Jewish refugees or opponents of the Nazi regime, the Turkish govern-

ment also officially contacted the Third Reich for visiting professors. The overt

admiration for German nationalism and its cultural production became evi-

dent in the official art and architecture of the state in the late 1930s and early

1940s. The monumental and ‘classical’ modernism of the Grand National

Assembly by Clemenz Holzmeister, the winner of an international competi-

tion in 1937, bears testimony to the strong relationship between architecture

and state power. The Ankara railway station by S¸ekip Akalın (1937) and the

TCDD State Railway headquarters by Bedri Uc¸ar (1941) are other important

examples of this monumental architecture, often featuring imposing stone

fac¸ades and symmetrical entrances with colossal colonnades rising to the entire

height of the building (see fig. 16.6). In the fall of 1942, Paul Bonatz brought

the Neue Deutsche Baukunst Exhibition, featuring the work of Albert Speer

and the architecture of the Third Reich, to an admiring Turkish audience.

The German influence on the Turkish arts of the 1930s is also evident in the

Atat

¨

urk and Victory monuments in Ankara, Samsun and Afyon by the German

sculptor Heinrich Krippel, and especially in the paradigmatic G

¨

uven Monu-

ment in Kizilay Square in Ankara (1935) by Anton Hanak and Josef Thorak.

With conspicuous similarities to Nazi state art, the latter features a sculp-

tural relief of Atat

¨

urk with a serious, frowning expression and flanked by

four naked, muscular youths, all resting against a granite wall atop a granite

base.

The ultimate nationalist state monument of the Republic, however, is

Atat

¨

urk’s mausoleum, or the Anıtkabır, perched on the Rasattepe hill in

Ankara, and designed by Emin Onat and Orhan Arda (1942–55). The result

of an international competition following the death of the national hero, the

438

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

Fig. 16.6 Opening of the Ankara railway station (1937) designed by S¸ekip Akalın

[Foto

˘

graflarla Yeni Ankara Garı, official photo album, author’s collection]

Anıtkabır is, in effect, a religious precinct adopting a temple form and a proces-

sional alley (see fig. 16.7). It is a potent monument to the Republican recasting

of the nation as a secular religion. Iconographic references to pre-Islamic

Anatolian civilisations, such as the Hittite lions along the processional axis

and decorative quotations from folk art and the coloured and gold mosaic

kilim motifs on the ceiling of the entrance portico make this design a perfect

built manifesto of the nationalist Turkish history theses promoted around

the same time. These theses traced the historical and linguistic origins of

the Turkish people to Central Asia and to successive migrations to Anatolia,

thereby giving a new nationalist significance to artistic/architectural refer-

ences to prehistoric Anatolian civilisations, Central Asian monuments and

other pre-Islamic structures.

22

Particularly significant were Hittite motifs and

figures which, to this day, constitute powerful symbols of secular Republican

nationalism.

22 A most paradigmatic work applying Turkish history theses to history of art and architec-

ture is C. E. Arseven, T

¨

urk sanatı (Istanbul: Milli E

˘

gitim Matbaası, 1928). This nationalist

text was central to art history and archaeology education in Istanbul and Ankara Uni-

versities, based on the founding ideas of Austrian and German scholars such as Heinrich

Gluck andKatharina Otto-Dorn, as wellas their TurkishstudentssuchasOktay Aslanapa.

439

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

Fig. 16.7 Anıtkabir, Atat

¨

urk’s mausoleum (1942–55), designed by Emin Onat and Orhan

Arda – the ultimate nationalist monument of modern Turkey

[photograph by the author]

If pre-Islamic history served to locate national identity in a distant, mythical

past, the vernacular folk culture of Anatolia offered another timeless source

for Turkishness, and rapidly became the central trope of the artistic and archi-

tectural culture of the period. Between 1937 and 1944, a travel programme for

artists was established by the RPP under the auspices of the People’s Houses.

It was intended to encourage artists to travel in Anatolia and paint the land-

scapes, houses, peasants, costumes, colours and folkloric characteristics of

Anatolian towns and villages. Similar nationalist programmes, ethnographic

studies and field research were carried out in many fields during this period,

particularly that of music. The Hungarian composer B

´

ela Bart

´

ok and his Turk-

ish colleagues travelled from village to village, collecting folk songs and tunes

that would be the primary ingredients in the making of a modern Turkish

music along Western lines.

23

In 1932, the art department of the Gazi Teachers’

College was established in Ankara, ending the Istanbul Academy’s monopoly

23 See A. A. Saygun, Bela Bartok’s Folk Music Research in Turkey (Budapest: Akademia Kiado,

1976).

440

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

of art education and soon becoming an important centre in the proliferation

of ‘Anatolian themes’ in Turkish art. As a major theme in Republican cultural

discourse, Ankara was portrayed as the embodiment of the youth, idealism,

patriotism and purity of the Kemalist

˙

Inkılap, in contrast with the old, imperial

and cosmopolitan Istanbul.

With the intensification of nationalist sentiments, Republican art critics,

novelists and intellectuals increasingly criticised the internationalism of the

modernist avant-garde, as well as the credo of ‘art for art’s sake’ in the late

1930s. Ali Sami Boyar’s essays in

¨

Ulk

¨

u are representative in this respect. ‘Before

paintings of magnolias and chrysanthemums’, he wrote, ‘we need paintings

that will depict our national legends.’

24

Likewise, writing in the illustrated

Republican weekly Yedig

¨

un, Peyami Safa attacked Cubism as ‘an aggressive

counter-cultural tendency, born out of post-war hysteria and cut off from any

ties to habit and tradition’.

25

Almost echoing the Nazi condemnation of the

avant-garde as a ‘degenerate art’, Halide Edip Adıvar saw the Cubist paintings

of Picasso as the expressions of a ‘psychologically disturbed mind’ and ‘cubic

architecture’ as a pathological phenomenon that ‘disturbs the eye’.

26

In his 1934

novel Ankara, Yakup Kadri Karaosmano

˘

glu described the coldness, sterility and

feeling of alienation embodied by a modern ‘cubic house’.

27

Addressing the

‘homelessness’ of modern lives, H

¨

useyin Cahit Yalc¸ın lamented the prolifera-

tion of ‘cubic apartments’, which, he observed, ‘have turned us into nomads

without home and a hearth’.

28

In this climate, the call for a ‘national art’ (milli sanat) and a ‘national archi-

tecture’ (milli mimari) became the motto of the most prominent artists and

architects of the early Republic, including the Group D members who had

initially introduced modernist trends such as Cubism, Purism, Expressionism

and Constructivism to Turkey. Distancing themselves from abstract, formalist

and individualist conceptions of art, they joined the academic establishment in

education and internalised the RPP ideology in practice. Prominent members

of the group such as Bedri Rahmi Ey

¨

ubo

˘

glu, Nurullah Berk and Cemal Tollu

adapted cubist techniques to Anatolian themes and folkloric motifs, produc-

ing what one art critic calls ‘a peasant cubism’ (k

¨

oyl

¨

u kubizmi).

29

Along the

same lines, the paintings of Turgut Zaim display a distinct Turkish ‘na

¨

ıve’

24 A. S. Boyar, ‘Sanat varlı

˘

gımızda resmin yeri’,

¨

Ulk

¨

u 5 (1934), p. 398.

25 P.Safa,‘BizdeveAvrupa’dak

¨

ubik’, Yedig

¨

un 8, 188 (1936), p. 8.

26 H. E. Adıvar, ‘Tatarcık: b

¨

uy

¨

uk milli roman’, Yedig

¨

un 12, 305 (1939), pp. 12–13.

27 Y. K. Karaosmano

˘

glu, Ankara (Istanbul:

˙

Iletis¸im, 1981 [1934]), pp. 124–5.

28 H. C. Yalc¸ın, ‘Ev ve apartman’, Yedig

¨

un, 11, 265 (1938), p. 5.

29 S. Tansu

˘

g, T

¨

urkresmindeyenid

¨

onem (Istanbul: Remzi Kitabevi, 1995), p. 86.

441

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

genre with his highly stylised and idealised paintings of peasant women and

children, Anatolian landscapes, mud-brick houses and poplar trees, folk arts

and crafts, kilims and copper pots.

30

Zaim also designed stage-sets for the pro-

ductions of the National Theatre, where the ballets, symphonies and operas

of Turkish composers inspired by Anatolian folk-tunes were performed. In

1940 the New Group of painters, formed by Nuri

˙

Iyem (1915–2005), Avni

Arbas¸(1919–2003), Selim Turan (1915–94) and Abidin Dino (1913–93), intro-

duced a new sociological content to Turkish art. Supported by the writings of

prominent sociologist and intellectual historian Hilmi Ziya

¨

Ulken, these artists

painted not just peasants and rural themes, but also the urban poor, workers

at the docks and many other subjects reflecting the social realities of the

country.

In architecture, Sedad Hakkı Eldem (1908–88) assumed the leadership of

the quest for a national architecture that was to emerge out of the native

soil, traditions and materials of the country, and would flourish directly under

the sponsorship of the state.

31

In 1934, he established a National Architecture

Seminar at the Academy dedicated to documenting the surviving examples

of traditional ‘Ottoman/Turkish houses’, which Eldem saw as the only viable

source of a national architecture movement. Inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s

prairie houses and very familiar with the work of modernist architects in Paris

and Berlin, Eldem saw the traditional wooden yalıs and konaks of Istanbul as

thoroughly rational and functional designs in terms of their plan types, con-

structional principles and programmatic layout.

32

He argued that the ‘Turkish

house’ was already ‘modern’ in its functional and constructional logic, and

hence the only viable source of the desired New Architecture. Through the

1930s, he built many villas and yalıs for the Republican elite, reinterpreting the

traditional wooden Turkish house in modern materials. His canonic Tas¸lık

Coffee House in Istanbul (1948, demolished in the 1980s), a reinforced con-

crete replica of a late seventeenth-century wooden yalı, was the ultimate built

manifesto of his ‘national architecture’ programme (see fig. 16.8). Ironically,

by the time it was built, the cultural climate in Turkey was already shifting in

parallel with the transition to a multi-party system in 1945 within the overall

post-war dynamics of the world at large.

30 The genre of painting popularised by Turgut Zaim was later continued in the work of

his daughter Oya Kato

˘

glu, another prominent Turkish painter.

31 S. H. Eldem, ‘Milli mimari meselesi’, Arkitekt (1939); S. H. Eldem, ‘Yerli mimariye do

˘

gru’,

Arkitekt (1940).

32 See S. H. Eldem, T

¨

urk evi (Istanbul: Tac Vakfı, 1984); also S. Bozdo

˘

gan, S.

¨

Ozkan and

E. Yenal, Sedad Hakkı Eldem: Architect in Turkey (Singapore: Concept Media, 1987).

442

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

Fig. 16.8 Tas¸lık Coffee House (1948) by Sedad Hakkı Eldem, a modern reinforced

concrete replica of a seventeenth-century wooden house, the Amcazade H

¨

useyin Pas¸a

Yalısı on the Bosporus; a canonic example of Second National Style in architecture

[Sedad Hakkı Eldem Archives, Istanbul]

Diversification of the scene: 1950–80

With the landslide election victory of the Democrat Party (DP) in 1950,a

new era opened up in modern Turkish history, marking the end of the RPP’s

hegemony over politics and cultural life. Turkey’s incorporation into the world

capitalist system led by the US after the Second World War, the onset of more

liberal economic policies, the modernisation of agriculture and the beginning

of migration to big cities constitute the backdrop for important developments

in art and architecture in this period. Closer ties with the US were forged

through the Marshall Plan in 1947, and Turkey’s geo-political position as an ally

of the West was ratified with her NATO membership in 1952. In the following

decade, Turkish society became increasingly more interested in American

443