Kasaba R. The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 4, Turkey in the Modern World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

labelled by architectural historians as the First National Style,

7

it combined

Ottoman forms and stylistic motifs with European design principles, building

types and construction techniques. Under the leadership of three prominent

practitioners and educators, Vedat Bey (1873–1942), Kemalettin Bey (1870–1927)

and the Levantine Italian architect Guilio Mongeri (1873–1953), architects exten-

sively applied this hybrid style to the programmatic requirements of a modern

state and modern urban life, not unlike its counterparts in Europe, such as

neo-classicism and Gothic Revival. Banks, offices, hotels, cinemas and other

public, urban structures were built in this style, first for the Young Turks and

subsequently for the Kemalist Republic.

In most of these buildings, classical Ottoman architectural elements (espe-

cially wide overhanging eaves, domes, pointed arches and ornate tile dec-

oration) were used as overt stylistic statements of Turkish identity applied

onto what were otherwise conspicuously ‘European’ buildings designed along

academic Ecole des Beaux Arts principles (symmetry, axiality and classic tri-

partite fac¸ade compositions) and Western construction techniques (steel and

reinforced concrete, in particular). Large public buildings such as Vedat Bey’s

Central Post Office (1909) or Kemalettin Bey’s Ministry of Endowments office

block in Sirkeci (1912–26) represent the most canonic, technologically advanced

and programmatically complex examples of this style, while numerous more

anonymous buildings, not just in Istanbul and Ankara but in many provin-

cial cities of Anatolia, testify to its pervasiveness and remarkable range of

experimentation. Although essentially academic and revivalist in its premises,

it is the modern self-consciousness of this style – its desire for national self-

representation and historical agency – that makes it ‘modern’. Reacting against

the stylistic plurality and eclecticism of the late nineteenth century (whenIstan-

bul was the scene of construction in a wide range of architectural styles, from

neo-classicism to art nouveau), the First National Style was a new patriotic

programme that sought to demonstrate the viability of classical Ottoman

forms and motifs, not only as the source of a ‘Turkish’ national expression in

architecture, but also as the source of a ‘modern’ style for the early twentieth

century with all its technological advances.

The predominance of this style in the design of practically all major public

buildings of the 1920s in the new capital city, Ankara, inevitably strengthens

its associations with the birth of the new nation. Particularly symbolic in

this respect is the modestly proportioned First National Assembly Building

7 Not to be confused with the Second National Style of the 1930sand1940s, which sought

inspiration from the vernacular traditions of the wooden Ottoman/Turkish houses.

424

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

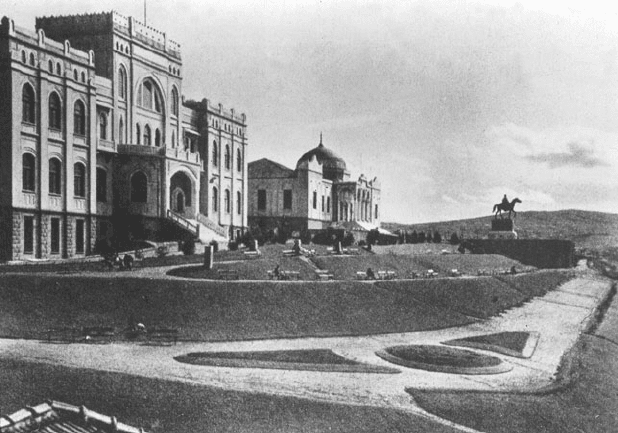

Fig. 16.1 Ottoman revivalist First National Style buildings in Ankara: Turkish Hearth

Building (1927–30) and Ethnography Museum (1926) by Arif Hikmet Koyuno

˘

glu

[photograph from the author’s collection]

(initially the CUP headquarters, today the Museum of the War of Indepen-

dence) designed in 1917 by

˙

Ismail Hasif Bey, an architect who died in the War

of Independence. Paintings depicting the opening day of the First National

Assembly in 1920 feature the building as the iconic backdrop to this heroic,

historical event. Other First National Style buildings were constructed in a

very short time in the same part of ‘old Ankara’ around the National Square

(Ulus Meydanı) below the Citadel. Among them is the Ankara Palas (1924–6),

the joint work of Vedat and Kemalettin, who produced an ornate hotel with

the latest technical infrastructure and modern conveniences to host the higher

bureaucrats and foreign dignitaries of the new Republic. Also notable are the

‘Ottoman’, ‘Agricultural’ and ‘Business’ bank buildings (1926–9) of Guilio Mon-

geri, as well as a group of representative public buildings by the younger Arif

Hikmet Koyuno

˘

glu, lined along the avenue to the south: the Ministry of For-

eign Affairs (1927), Ethnography Museum (1926) and Turkish Hearth Building

(1927–30), which collectively display the ornate aesthetics of this style, with its

marble fac¸ades, tile decoration, Ottoman domes and ‘crystalline’ column cap-

itals with muqarnas details (see fig. 16.1). Similarly detailed First National Style

425

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

buildings proliferated in other cities of Republican Anatolia, such as Izmir,

Konya, K

¨

utahya and Sivas among others, as government ‘palaces’ (h

¨

uk

¨

umet

kona

˘

gı), schools, post offices and other public buildings.

To this day, one of the most contentious topics in the historiography of

modern Turkish architecture is the status and appropriateness of the First

National Style as the aesthetic expression of a new, secular and modern repub-

lic at a time when the new regime was seeking to dissociate itself from its

Ottoman/Islamic past through a series of radical Westernising reforms. Many

architectsand architectural historians, having internalised the modernist biases

of the Republic after 1931, tend to see this style as a ‘temporary aberration’

at best, dismissing its academic premises and historical references as anath-

ema to the revolutionary modernism of the Kemalist project. Yet, far from

being an anachronistic architecture, the First National Style was in fact a

most appropriate expression of the volatile transition period from empire to

republic. Its Ottoman stylistic references applied to modern building types

were effectively ‘double-coded’, capable of signifying both the glories of an

Ottoman/Islamic past (necessary for national pride) and the new realities of

a society in transformation. What eludes the modernist critics of this style is

that in the late 1920s old allegiances to religion, the sultan, Istanbul and aca-

demic traditions of art and architecture coexisted with new allegiances to the

nation, Atat

¨

urk, Anatolia and the modernist currents originating in Europe,

for artists and architects just as for everyone else. As many scholars point out,

in this period religion remained a powerful force for national mobilisation,

and the nation was conceptualised as a kind of secular religion.

8

Symptomatic

in this respect are the Atat

¨

urk portraits of this period, showing the national

hero in his Gazi outfits (the word gazi signifying a ‘fighter for faith’) wearing

the kalpak headgear (rather than the ‘panama hat’ he preferred after 1931)and

sometimes displaying overt references to the religious and aesthetic codes of

Islamic miniature painting.

9

Overall, the 1908–31 period marks the emergence of a modern artistic

and architectural culture (encompassing the totality of institutional practices,

schools, exhibitions, publications and organisations, all of them informed

8 Most significantly by S¸erif Mardin: see his Religion and Social Change in Modern Turkey

(Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989); and ‘The Just and the Unjust’, Deadalus

3 (Summer 1991).

9 As for example in a 1923 painting by Tahirzade H

¨

useyin titled Gazi Mustafa Kemal Pas¸a

Hazretleri, representing Atat

¨

urk’s portrait as surrounded by angels and border illumi-

nations like those used in miniature paintings of the Prophet Muhammad’s life. For a

reproduction of the painting see G. Elibal, Atat

¨

urk ve resim heykel (Istanbul:

˙

Is¸Bankası

K

¨

ult

¨

ur Yayınları, 1973).

426

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

by a new nationalist self-consciousness). One important development

underscoring the new era, for example, was the rise of Muslim/Turkish artists

and architects to influential leadership positions formerly held by Armenians,

Greeks or Europeans. In the painting studios of the Imperial Academy of Fine

Arts in Istanbul (Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi Alisi, established in 1882), the primary

institution for the training of artists and architects until the end of the early

Republican period, the academic instruction of Salvatore Valeri and Warnia

Zarzecki gave way to the modernist teachings of the 1914 generation. Like-

wise, the Armenian sculpture teacher Oskan Yervant Efendi retired in 1908

and was replaced by

˙

Ihsan

¨

Ozsoy (1867–1944) and the German-educated Nijad

Sirel (1897–1957). Meanwhile, in the architectural studios, Vedat Bey (trained in

the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris) succeeded Alexander Vallaury as the head of

the architecture section. The other leading architect of the Ottoman revivalist

First National Style, Kemalettin Bey (trained in Charlottenburg Technische

Hochschule in Berlin), taught architectural courses to engineering students in

the Civil Service School of Engineering (Hendese-i M

¨

ulkiye Mektebi, estab-

lished in 1884) and also trained many young architects throughout his dis-

tinguished career as the chief architect/restoration expert of the Ministry of

Endowments (Evkaf Nezareti).

In 1914, to accommodate female art students, a sister school to the Academy

was established (Inas Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi) under the directorship of Mihri

M

¨

us¸fik Hanım (1886–1954), a talented artist and colourful personality, ‘some-

times veiled, sometimes elegantly dressed in high heels and straw hats adorned

with flowers–aliving testimony to the mixture of the alaturka and the

alafranga’, as one art historian puts it.

10

In 1926, the two schools were com-

bined and the Academy formally approved the admission of girls. Equally

significant was the institutionalisation of the new practice of working with

nude models after 1917, an unprecedented step in a traditional and predomi-

nantly Muslim society. The foundation of the Society of Ottoman Painters in

1909 (Osmanlı Ressamlar Cemiyeti), the publication of its magazine Osmanlı

Ressamlar Cemiyeti Mecmuası and the initiation of more systematic annual art

exhibitions in the Imperial Lyc

´

ee of Galatasaray are also important milestones

in modern Turkish art. With the end of the empire in 1921, the Society of

Ottoman Painters renameditself the Society of Turkish Artists (T

¨

urk Sanatc¸ılar

Birli

˘

gi) and opened its first exhibition in Ankara in 1923 on the occasion of the

proclamation of the Republic.

10 Tansu

˘

g, C¸a

˘

gdas¸T

¨

urk sanatı,p.137.

427

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

As is frequently pointed out by art historians, successive modern currents

from Europe were introduced to Turkey only after the eclipse of their initial

critical force in Europe. At a time when all traditional conceptions of art

were being radically shaken in Europe by the avant-garde currents of Cubism,

Futurism, Dada and Constructivism, the Impressionism of the 1914 generation

was as ‘modern’ as Turkey got in the midst of her own turmoil during the

disintegration of the empire. This ‘time lag’ does not mean, however, that a

linear historical trajectory based on European developments should be the

only yardstick against which Turkish artists can be viewed and judged. Rather,

the significance and contributions of each generation acquire meaning only in

the context of the specific historical circumstances of Turkey. It is in this sense

that Impressionism in painting and the Ottoman revivalist First National Style

in architecture can be seen as the ‘first moderns’ in Turkey, even when their

‘modernity’ was a belated one by European standards and chronologies.

By the late 1920s, however, the demise of the ‘first moderns’ was already

under way. In painting, a new group of younger artists was challenging the

Impressionism of the 1914 generation, which, they claimed, had itself become

an academic tradition rather than a critical, new current. This group of artists,

including prominent painters such as Refik Epikman (1902–70), Mahmut Cuda

(1904–87), Elif Naci (1898–1988) and Turgut Zaim (1906–74) gathered around

the Association of Independent Painters and Sculptors (M

¨

ustakil Ressam ve

Heykeltras¸lar Birli

˘

gi, established in 1929), representing a wide range of artistic

trends irreducible to a common denominator. They acknowledged the influ-

ence of European avant-garde currents such as Cubism, experimented with

these influences in landscape, figure and still-life paintings, and at the same

time sought inspiration in the Anatolian folk sources of Turkish culture – a

trend that would turn into a major nationalist programme in art after 1931.

In architecture, a series of major curricular reforms launched at the

Academy of Fine Arts in 1926 prepared the ground for the final demise of

the First National Style. The school was renamed, in modern Turkish, G

¨

uzel

Sanatlar Akademisi, and was relocated to one of the shore palaces along the

Bosporous under the directorship of the painter Namık

˙

Ismail. An Austrian-

Swiss architect, Ernst Egli, was appointed as the head of the architectural

section where the curriculum was radically redesigned, replacing the classical

Beaux-Arts model with the rationalist and functionalist precepts of Euro-

pean modernism already on the rise in Europe. Younger architects infatuated

with modernism cast aside the teachings of Vedat Bey and Guilio Mongeri.

Increasingly, these new modernists characterised the First National Style as

modernism’s stylistic and anachronistic ‘other’, which had to be left behind

428

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

in order to capture the Zeitgeist of the modern age. Prominent intellectuals

such as Ahmet Has¸im criticised Ottoman revivalist buildings as ‘a reactionary

architecture (m

¨

urteci mimari)’.

11

Influential art historians such as Celal Esat

Arseven celebrated the arrival of the ‘New Architecture’ (Yeni Mimari)asthe

European Modern Movement was then called, characterising the curricular

transformations at the Academy as the emancipation of the architect from ‘the

stifling of talent by classicism’ and hailing the progressive redefinitionof the dis-

cipline of architecture ‘in response to contemporary needs and mentalities’.

12

The newly founded Society of Turkish Architects in Ankara (T

¨

urk Mimarlar

Cemiyeti, 1927) and the Fine Arts Association in Istanbul (G

¨

uzel Sanatlar Birli

˘

gi,

1928) became the breeding grounds of the young, modernist and anti-academic

crusade in architecture, which effectively aligned itself with the revolutionary

zeal of Kemalism. By 1931, the triumph of the ‘NewArchitecture’was complete.

With the more unequivocally secular and Western-oriented cultural politics

of the Republic firmly established, artists and architects sought to dissociate

Republican works from any references to the country’s Ottoman/Islamic past.

Today the physical fabric of Ankara bears the traces of this decisive shift around

1930 in the style of architecture employed for its public buildings. The First

National Style buildings of the 1920s are located in the older section of the city

to the north, while the austere German and Central European modernism of

the 1930s characterises the newer southern extension of the city, appropriately

called Yenis¸ehir or ‘the new city’.

Art/architecture and the state: 1931–50

The series of radical institutional reforms in the late 1920s, which were carried

out under the personal directive of Atat

¨

urk, collectively amounted to a total

civilisational shift from a traditional order grounded in Islam to a modern,

Western and secular one. The revolutionary self-consciousness of Kemalism,

the founding ideology of the Republic, is most evidentin its self-representations

referring to the image of the French Revolution. One especially remarkable

example is the 1933 painting by Zeki Faik

˙

Izer titled

˙

Inkılap Yolunda (On the

Path of the Revolution) (see fig. 16.2). With overt allegorical references to the

1830 Eug

`

ene Delacroix painting Liberty Leading the Nation, it is a portrayal of

the Kemalist Revolution as a popular insurgence of the Turkish people against

11 A. Has¸im, Gurabahane-i laklakan (Ankara: Turkish Ministry of Culture, 1981 [1928]),

pp. 154–7.

12 C. E. Arseven, Yeni mimari (Istanbul: Agah Sabri K

¨

ut

¨

uphanesi, 1931), which was adapted

from Andre Lurcat, L’Architecture (Paris: Rene Hilsum, 1929).

429

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

Fig. 16.2

˙

Inkılap Yolunda (On the path to revolution), by Zeki Faik

˙

Izer (1933)

[courtesy of Sadi

˙

Izer; reproduced from G

¨

ultekin Elibal, Atat

¨

urk ve Resim Heykel (Istanbul:

˙

Is¸ Bankası K

¨

ult

¨

ur Yayınları, 1973)]

the darkness and anachronism of Turkey’s ancien r

´

egime. The painting suggests

a violent national upheaval (soldiers, bayonets and flag), guided by Mustafa

Kemal himself and equipped with scientific knowledge and youthful energy

(books, torchlight and young people in Western clothes). Mustafa Kemal’s own

words were no less allegorical when he characterised ‘civilisation’ as ‘a sublime

force, which pierces mountains, crosses the skies, enlightens and explores

everything from the smallest particle of dust to the skies’.

13

Furthermore, in

his eyes it was a matter not of choice but of necessity to follow this ‘sublime

force’, represented in the real world by the social and material progress of the

West.

Within this progressive model of history, many artists and intellectuals

subsumed the term ‘culture’ under the broader term ‘civilisation’, defining

the latter as an irresistible process of social evolution in which scientific and

technological development assumed a historical agency. In a 1933 article titled

‘Culture and Civilization’in the magazine Kadro, Yakup Kadri Karaosmano

˘

glu,

the leading novelist and political figure of the early Republican period, rejected

Ziya G

¨

okalp’s earlier distinction between the two terms in favour of a new,

13 Atat

¨

urk’

¨

un s

¨

oylev ve demec¸leri, vol. II (Ankara: T

¨

urk Tarih Kurumu, 1959), p. 212.

430

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

unified concept of contemporary civilisation.

14

Grounded in scientific and

technological progress, this new concept of civilisation was also expected to

be the basis of the cultural and artistic regeneration of the nation. In the early

1930s, many authors articulated this necessary relationship between the desired

new art/architecture of the Kemalist Revolution, and the new technological

epoch. Echoing and sometimes directly translating from the discourse of the

modernist avant-garde in Europe, Turkish artists and architects wrote that

the source of inspiration for this new art/architecture could no longer come

from classical styles, monuments and traditions, but had to be found in the

machines, automobiles, ocean liners and aeroplanes of the modern age.

15

Although Turkey in the 1930s was far from being anywhere near reaching the

aspired-to ‘machine age’, the utopian image of a modern and industrialised

Turkey was exalted by the visual culture of the Republic. Endlessly reproduced

in official Republican publications, factories, railways, dams, trains, planes and

industrial buildings acquired an unprecedented artistic appeal. In terms of this

revolutionary emphasis on industrial development and on the linking of art

with politics, many parallels can be drawn between early Republican Turkey

and the Futurist and Constructivist fascination with the technological and

industrial icons of the modern age in Fascist Italy and Soviet Russia.

Yet the cultural politics of the early Republic also contained certain ambi-

guities and complexities specific only to the Turkish experience. Most sig-

nificantly, there were two ‘civilizational others’ against which a national cul-

ture was expected to assert itself. Not only was Turkey’s own traditional

Ottoman/Islamic past portrayed as standing in the way of progress, but the

highly individualistic, materialist and cosmopolitan lifestyles of the capitalist

West were also declared to be enemies of the kind of nationalism, idealism and

populism that the RPP sought to create. Western civilisation was the model to

be emulated for scientific and technological progress, but this idealised ‘civilisa-

tion’ had to be grounded in the country’s native soil and national morals. Con-

sequently, having already rejected Ottoman/Islamic precedents, early Repub-

lican nationalism instead turned to Anatolia’s folk culture and the pre-Islamic

heritage of the Turks. As the theories, forms and techniques of European

modernism infiltrated artistic and architectural production in Turkey, Ana-

tolian themes, folkloric motifs and nationalist symbols also became central

preoccupations of the Turkish cultural scene.

14 Y. K. Karaosmano

˘

glu, ‘K

¨

ult

¨

ur ve medeniyet’, Kadro 15 (1933).

15 For example, B. Asaf, ‘Neden sanatsızız?’, Kadro 13 (1933); A. Ziya, ‘Yeni sanat’, Mimar 2

(1932).

431

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

The entire artistic and architectural culture of the 1931–50 period can be

viewed as an arena in which this profound tension played itself out and artists

explored ways of ‘nationalising the modern’ or ‘modernising the national’,

depending on how one chooses to characterise it. The cultural discourse of

the period was dominated by the desire to show the world that the terms

‘national’ (meaning ‘Turkish’) and ‘modern’ (meaning ‘Western’) were not

really antagonistic if Turkish artists could rid themselves of the contaminating

elements of oriental Islamic culture. As the prominent painter Nurullah Berk

put it, ‘the modernity, compositional simplicity, rationalism and harmony of

Turkish art’ were celebrated as qualities distinguishing it from the oriental

character of ‘Arabic, Persian and Indian art’.

16

Many other Turkish scholars

and intellectuals, such as the art historian/critic Celal Esat Arseven or the

archaeologist Ekrem Akurgal, articulated the same theme, pointing out the

differences between Central Asian/Anatolian Turkish art and the art of other

Islamic cultures, and explaining how Turkish art was closer to the humanistic,

rational and tectonic conceptions of Western art, from its origins in classical

antiquity to its modern industrial phase.

Even a cursory survey of the art and architectural publications of the 1930s

reveal a passionate preoccupation with giving form to the Kemalist

˙

Inkılap

(Revolution), with extensive debates on what constituted its appropriate artis-

tic and architectural expression (

˙

Inkılap Sanatı and

˙

Inkılap Mimarisi respec-

tively). Revolution was the keyword, and revolutionary regimes elsewhere in

the worldofferedinspiring models. A Russian painting and sculpture exhibition

opened in Ankara in 1934 to an enthusiastic reception. Some Turkish artists

observed the organic link between the Italian avant-garde artists/architects

and Mussolini’s fascist revolution with admiration throughout the 1930s. Rev-

olution and the Arts was the theme of the first

˙

Inkılap Exhibition in Ankara

in 1933, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the Republic.

17

This exhi-

bition, and similar ones in subsequent years, featured paintings depicting the

accomplishments of Kemalist reforms and nation building, especially scenes

of agriculture and industry, railways, modern women, school children and

educational reforms. Most significant in the popularisation of art under the

auspicesof the RPP’sofficialideology wasthe establishmentof People’sHouses

16 N. Berk, Modern Painting and Sculpture in Turkey (New York: Turkish Information Office,

1955).

17 This exhibition was inspired by the Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista of 1932 in Italy,

celebrating the tenth anniversary of Mussolini’s march into Rome. Turkish architect

Aptullah Ziya visited the exhibition and wrote about the need to emulate what the

Italians accomplished in creating an art/architecture of their revolution.

432

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

(Halkevleri) in 1932 and the publication of its journal

¨

Ulk

¨

u (Ideal) after 1933.

With branches in every major Anatolian town, the People’s Houses served as

cultural centres for arts, drama, music, sports, popular education and popular

indoctrination designed to foster a Republican generation committed to the

ideals of the

˙

Inkılap.

18

The singular most defining feature of this period was the absolute and

almost exclusive predominance of state patronage and official ideology in mat-

ters of art, architecture and culture.

19

The contents of the official propaganda

publication La Turquie Kemaliste, published primarily for foreign observers and

international publicity, illustrate the importance of exhibitions, museums, the

‘new architecture’, archaeology, modern painting and sculpture for displaying

the cultural accomplishments of the young Republic (see fig. 16.3). The idea of

a National Painting and Sculpture Museum was finally realised in this period,

when the government converted one wing of the Dolmabahc¸e palace for this

purpose in 1937. A programme of annual state painting and sculpture exhibi-

tions (devlet resim ve heykel sergileri) was institutionalised also in 1937, at which

awards were given out and selected works acquired for the permanent state

collection. Throughout the early Republican period, these state-sponsored

exhibitions remained the only venue for many artists to display their work to

the public. Many art historians characterise this as ‘the primary handicap of

modern Turkish painting and sculpture’, depriving it of constructive exchange

with critical opinions, and hence from the real creative dynamics that govern

the arts in the capitalist world.

20

The dependence upon the state is even more obvious in the case of architec-

ture, which, as a technical profession different from the plastic arts, has always

depended on a powerful clientele to flourish. In the conspicuous absence of an

autonomous bourgeoisie class in Turkey, the state was the primary client for

the profession until the 1950s, while public buildings representative of the state

constituted the only major design commissions. Government buildings and

municipal offices, railway stations, post offices and perhaps most representa-

tive of the ideological programme of the RPP, schools and People’s Houses,

are the most characteristic building types of this official architecture. Also rep-

resentative are the three major infrastructure projects of Republican Ankara

18 For the significance of the People’s Houses in the architectural culture of the period see

N. G. Yes¸ilkaya, Halkevleri, ideoloji ve mimarlık (Istanbul:

˙

Iletis¸im, 1999).

19 For an overview of the relationship between politics and culture in this period, see

Bozdo

˘

gan, Modernism and Nation Building;D.K

¨

oksal, ‘Art and Power in Turkey: Culture,

Aesthetics and Nationalism during the Single-Party Era’, New Perspectives on Turkey 31

(Fall 2004).

20 Tansu

˘

g, C¸a

˘

gdas¸ Turk sanatı,p.218.

433