Kasaba R. The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 4, Turkey in the Modern World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

Fig. 16.18 Kanyon Tower residences/shopping mall in Istanbul (2001–6) designed by Jerde

Partnership/Tabonlıo

˘

glu Architects and Arup Engineers

[photograph by the author]

and international experience, has elaborated a formalism and high-tech expres-

sionism illustrated by such projects as his Dikmen Valley ‘bridge’ in Ankara

(1996), commercial centre for Vakıf Real Estate Investment Company also in

Ankara (2000–1) and his highly controversial S

¨

uzer Plaza tower, known as the

‘Skyframe’ (G

¨

okkafes) in Istanbul (1991). Likewise, Ragıp Buluc¸(b.1940) has

worked with the contemporary universal language of glazed malls and atria,

as in the case of his Atakule shopping mall in Ankara (1989), with an observa-

tion tower containing a rotating restaurant. Do

˘

gan Tekeli and Sami Sısa, the

designers of the highly acclaimed Lassa tyre factory in

˙

Izmit in the 1970s, have

continued their mastery of industrial buildings and large-span structures with

such recent projects as the Eczacibas¸ı pharmaceutical plants in Luleburgaz

(1992), the Antalya airport international terminal (1998) and the Metrocity

tower residences/shopping mall in Istanbul (1997–2003), the popularity of the

latter to be eclipsed three years later by the adjacent Kanyon Tower shopping

mall designed by Jerde Partnership/Tabanlıo

˘

glu Architects and the structural

engineers of Arup Associates (see fig. 16.18). The mastery of cutting-edge

464

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

technology, new materials and advanced construction systems has dramati-

cally increased, making it no longer surprising for Turkish architects/design

firms to work with complex programmes and technologically challenging

structures such as airports, concert halls and auditoria. The Sabiha Gokc¸en

airport in Istanbul (2000–1) and the Bilkent University concert hall in Ankara

(1998–9) by Erkut S¸ahinbas¸ are two award-winning examples.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the appeal of postmodernism has also

prompted architects such as Merih Karaaslan to seek new approaches to resi-

dential architecture by breaking the monotony of the conventional apartment

block with formal playfulness and the use of colour. Even the older generation

of well-established architects, such as Behruz C¸ inici (b. 1932) and S¸evki Vanlı

(b. 1926), has experimented with new forms, historical and contextual quo-

tations and a generally more colourful architecture, as in the case of C¸ inici’s

higher-end Platin Residences in Istanbul (1994–9). The architecture of hotels

and holiday villages has emerged as a major category parallel to the expan-

sion of the tourism sector after 1980. Tuncay C¸ avdar (b. 1934) has attracted

both praise and criticism for his exuberant holiday villages along the south-

ern coast of Turkey near Antalya, combining the international language of

‘playful postmodern vacation architecture’ with the local climate and archi-

tectural iconography of the Mediterranean. The hotels of Ahmet I

˘

gdırlıgil

(b. 1955) in the Bodrum peninsula, where he resides and works, continue to

display the Aegean stone vernacular traditions in a kind of contemporary

regionalism.

Since the 1990s, a younger generation of Turkish architects has achieved

remarkable success in transcending traditionalist, regionalist and/or postmod-

ernist clich

´

es, as well as the clich

´

es of an international corporate architecture,

in favour of beautifully crafted work that can be contextual and universal at the

same time. The recognition of such work by the annual National Architecture

Awards (Ulusal Mimarlık

¨

Od

¨

ulleri) of the Turkish Chamber of Architects and the

publication of anthologies such as the Architectural Yearbooks by Kolleksiyon, a

leading furniture/interior design firm, have substantially increased the visibil-

ity of quality design in architecture. Among these, Han T

¨

umertekin’s (b. 1958)

B-2 House in Ayvacık, C¸ anakkale overlooking the Aegean, the recipient of the

prestigious A

˘

ga Khan Award in 2004, stands out. This small weekend house

for an urban client is a minimally simple yet conceptually sophisticated design

sensitively situated in the landscape. The same tectonic qualities, celebration of

textured materials, working with the landscape and an overall minimalist mod-

ern sensibility can be seen in the residential designs of Nevzat Sayın (b. 1954),

Emre Arolat (b. 1963) and S¸evki Pekin (b. 1946), among others. These architects

465

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

have also designed many large, complex industrial programmes, offices and

corporate buildings which are executed with a level of quality detailing that has

only recently become possible in Turkish construction scene. Nevzat Sayın’s

G

¨

on leather factories (1994–5) and Emre Arolat’s Istanbul Textile and Apparel

Exporters’ Association offices (1999–2000) are two notable examples. In 2006

Arolat’s design for the Dalaman airport won the prestigious Emerging Archi-

tecture Awards of the London-based Architectural Review, further testifying to

the increasing maturity of contemporary Turkish architecture.

The connection established with the rest of the world in matters of art and

architecture is the single most important and visible accomplishment of the

period. A more confident Turkey is no longer limited to importing interna-

tional trends, but has started in the direction of becoming an exporter of artistic

and architectural production and a recognised participant on the global scene.

One very important development in this period has been the appearance of

large corporate design, engineering and construction firms such as MESA

and STFA, entering the free-market economy with full force and forming

the fourth major sector of Turkish economy alongside textiles, tourism and

finance. These firms have not only built extensive housing and public works

projects within the country, but have also undertaken big commissions abroad,

especially in the Middle East, Gulf States, Russia and other republics of the

former Soviet Union. Equally significant has been the progressive integration

of Turkey into a global art and design network, parallel to the country’s rekin-

dled prospects for EU membership and the concomitant efforts to refashion

Istanbul as a ‘world city’ worthy of international attention. In architecture,

professional organisations and private-sector sponsorship have been effective

in inviting international celebrities such as Peter Eisenman, Bernard Tschumi

and Zaha Hadid to Turkey, culminating in Istanbul’s colourful hosting of the

UIA World Architecture Congress in 2005.

In art, the organisation of international exhibitions and events under the

leadership of competent curators such as Vasıf Kortun and Beral Madra, espe-

cially the institutionalisation of the Istanbul Biennale since 1987, has dramat-

ically elevated the image of Turkish art abroad and increased its connections

with the international art market. Historical buildings such as the church of

St Irene and the Baths of Haseki Sultan and Ottoman industrial buildings such

as the historical Feshane were used as temporary settings for Biennale exhi-

bitions throughout the 1990s. The foundation of Sanart in Ankara in 1992 as

the resourceful organiser of international art symposia and exhibitions has

also been significant. An even more spectacular boost to Turkey’s visibility has

been the opening of major private museums in Istanbul with the wealth of the

466

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

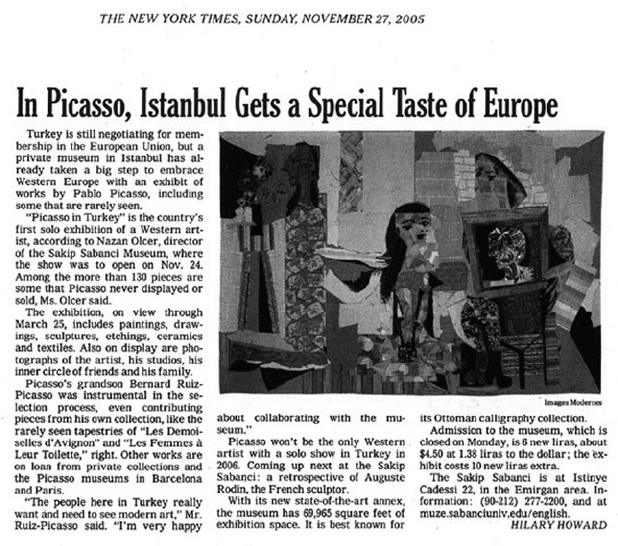

Fig. 16.19 New York Times article on the Picasso Exhibition in Sabancı Museum Istanbul, 27

November, 2005

[

c

New York Times; reprinted with permission]

country’s top industrialists turned patrons of art and culture. The Rahmi Koc¸

Museum of Industry, converted from the old industrial buildings of Ottoman

shipyards along the Golden Horn, opened in 1994 as Turkey’s first technology

museum. The Sabancı Museum in Emirgan, which opened in 2002 featuring

the Sabancı family’s calligraphy collection and a rich selection of late Ottoman

and modern Turkish paintings, has drawn international attention with the

opening of a Picasso exhibit in the summer of 2005, another important ‘first’ for

Turkey (see fig. 16.19). The latter was attended by the Turkish public in record-

breaking numbers, a rather unprecedented event in a country where modern

avant-garde art has historically been viewed with nationalist contempt.

The crowning achievement of the cultural promotion campaign on the eve

ofthe EU’s acceptance ofTurkey’s candidacy was theinauguration ofThe Istan-

bul Modern in December 2004 as the country’s first museum of modern art.

467

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

The elegantly modern and spacious galleries, caf

´

e and gift shop of the Istanbul

Modern, all contained in a simple reinforced concrete frame building, one of

the existing warehouses of the Galata harbour, were designed by Tabanlıo

˘

glu

Architects. Spectacularly located at the entrance to the Bosporus, the Istan-

bul Modern has done more for Turkey’s image abroad than years of official

government publicity programmes. The permanent exhibitions feature a rep-

resentative national collection of late Ottoman and Republican Turkish artists,

most of them from the collections of another leading industrialist family, the

Eczacıbas¸ı Foundation. A busy schedule of thematic exhibits and retrospective

shows is currently in the works under the leadership of the talented curator

Rosa Martinez. Acknowledging this new liveliness of the art scene in Istanbul,

a 2005 article in the New York Times observed, albeit with the familiar orientalist

overtones, that ‘contemporary art is now blooming among the minarets’.

49

The vitality of the cultural scene in Istanbul does give a glimmer of hope

in these troubled times, supporting the desired compatibility of a predomi-

nantly Muslim country with the culture, aesthetics and politics of modernity.

The liveliness, energy and plurality of the art/architectural scene since the

1980s have done a lot to challenge the authoritarianism and doctrinaire posi-

tion of traditional Republican cultural politics, not to mention its elitism.

Today, compared to their early Republican counterparts, both the producers

and the consumers of art and architecture come from different classes, cul-

tures and political persuasions, working with a multiplicity of aesthetic codes

from the low to the high end. Examples of beautifully designed and crafted

architectures, built with cutting-edge technologies and high-quality materi-

als, coexist with technically substandard, aesthetically banal and environmen-

tally unsustainable buildings that make up the majority of the urban fabric in

most Turkish cities. Internationally acclaimed art shows in the Istanbul Mod-

ern or other private art galleries in Istanbul address an elite audience while

more traditional, poorer crowds flock into public places such as Minyat

¨

urk –

an architectural theme park which opened along the Golden Horn in 2004

(see fig. 16.20).

Yet there are also legitimate reasons for concern, such as the potential pitfall

of a standardless relativism, where ‘anything goes’ in an increasingly aggressive

free market. Already, the overproduction and fast consumption of artistic and

architectural ideas and trends have become matters of concern for critics.

50

In

the workings of the art/architectural market, the organisation of exhibitions

49 New York Times, 28 August 2005.

50 See for example, B. Madra, ‘1997 ve sonrası ic¸in c¸a

˘

gdas¸ sanata ilis¸kin d

¨

us¸

¨

unceler’, Arrede-

mento Dekorasyon (February 1997 and March 1997).

468

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

Fig. 16.20 Minyat

¨

urk: architectural theme park along the Golden Horn (2004) with scale

models of architecture from Seljuk, Ottoman and modern Turkish periods

[photograph by the author]

or the commissioning of architects for big projects, there is frequently a con-

spicuous absence of a theoretical position, a clear ideological stance or even a

consistency in the selection of names. Like everywhere else in a rapidly glob-

alising world, the critical edge of cultural production in Turkey can be quickly

blunted by market imperatives. One needs to look no further than the recent

eagerness of the conservative ‘Islamist’ AK Party government to generously

open up Istanbul’s precious real estate to international corporate developers

for new commercial, residential and tourism projects, such as the highly con-

troversial proposal for two high-rise towers in Istanbul, dubbed the ‘Dubai

Towers’ in reference to the Gulf capital behind them. As many commentators

point out, the ‘programmatic dimension’ of Turkish modernity, which has

shaped and reshaped the country since the proclamation of the Republic, also

embodies a ‘destructive dimension’ that continues to erase the traces of its

own history and its own collective memory.

51

51 Ali Cengizkan, Modernin saati (Ankara: Mimarlar Derne

˘

gi, 2002).

469

s

˙

ibel bozdo

˘

gan

Conclusion

At the risk of oversimplification, it is possible to look at the history of mod-

ern Turkish art and architecture in the Republican period in terms of two

parallel but contradictory processes. On the one hand, since its institution-

alisation under the ideological auspices and patronage of the Kemalist state,

modern artistic/architectural production in Turkey has come a long way in

emancipating itself from official cultural politics, towards a relatively more

‘autonomous’ status. Especially since the 1980s, artists and architects are cater-

ing to an increasingly diverse private clientele and focusing increasingly more

on specific professional and disciplinary concerns (such as matters of form,

style, cutting-edge technologies, media, market etc.) rather than on the single

ideological mission of giving form to modern/national Turkish identity. On

the other hand, also since the 1980s, in the context of the increasing polarisa-

tion of Turkish culture and politics between the secular/nationalist old guard

and their liberal and/or Islamist challengers, art and architecture often find

themselves pulled back into the centre of politics once again, often with sur-

prising new alignments that defy traditional definitions of progressive versus

conservative, left versus right, modernist versus traditionalist etc.

For example, it is not without a certain amount of irony that in their effort

to market Istanbul as a world city, it is the conservative, Islamist municipal-

ity of Istanbul that is taking bold initiatives to invite the international stars

of contemporary architecture to tackle the city’s formidable urban, environ-

mental, ecological and aesthetic problems (as in the case of two interesting

and insightful recent projects by Zaha Hadid and Ken Yeang for the Kartal

and B

¨

uy

¨

ukc¸ekmece districts of Greater Istanbul respectively), while the ‘mod-

ernist’ architectural establishment is putting up an ideologically motivated

nationalist opposition to such initiatives, declaring them ‘an insult to Turkish

architects carrying the blood of the great master Sinan’.

52

This is not to say

that the new architectural/urban proposals of the AK Party are without seri-

ous problems. On the contrary, the haste and eagerness with which Istanbul

and coastal Turkey are being opened up to new construction, commercial

development and global tourism, often with little regard for their social and

environmental impacts, are indeed troubling. Yet, rather than launching a

constructive, expertise-based critique of the projects themselves, the reaction

often takes the form of an ideologically charged anti-globalisation, anti-Islamist

52 Declaration by the Turkish Chamber of Architects, Ankara, 7 April 2006.

470

Art and architecture in modern Turkey

discourse, anachronistically evoking the isolationist nationalism of the early

Republic.

A concluding observationcould be that while individualtalent and creativity

have never been lacking in modern Turkey, as a collective enterprise Turkish

artistic/architectural culture has mostly been framed by larger political, ideo-

logical and economic agendas that have blunted its creative and critical edge.

Between serving the authoritarian secular nationalism of the early Republic,

on the one hand, and offering commodified postmodern ‘pastiche’ for today’s

global market (including ‘Islamic’ identity statements), on the other, there has

been very little room for more nuanced, alternative, critical positions in art

and architecture. It is only in the 1950s and 1960s, when the official cultural

politics of the early Republican regime was somewhat relaxed and the dual

forces of global capitalism and political Islam had not yet risen up, that art and

architecture seems to have enjoyed a brief period of precisely such an opening.

It is a period to which we cannot help but look back with a certain amount of

nostalgia today.

471

17

The novel in Turkish: narrative tradition

to Nobel prize

erda

˘

gg

¨

oknar

Introduction: historical context and literary periods

An ongoing debate persists about the literary canon in Turkey. Does Turkey

actually have such a canon? If so, what merits inclusion? What are the texts

that might establish the canon? The debates are pertinent to this survey in that

they attempt to describe not only the characteristics of literature in Turkey,

but to catalogue the mix of figures, images and tropes at play in that literature.

As a framework for a literary survey, the canon is useful for tracking a pro-

gression of genres and themes, for identifying local and foreign influences, and

for revealing a projected ‘reader-citizen’. The audience of any canon is in one

respect the ‘nation’, imagined or otherwise. Furthermore, as a body of texts

that are models of form and content, the canon is one way to determine the

changing cultural logic of a national tradition as well as the sites of its politi-

cal and ideological power. (It hardly bears emphasis that literary production

in Turkey is political.) In a context of traditional narratives transformed by

European influences, the Ottoman and Turkish novel functioned to mediate

contradictory forces and to open up new sites of identification. There is per-

haps no better anthropological or aesthetic artefact with which to read social

change, to gauge resistance and to trace the scars of history and ideology on

local populations than the novel. In the process of ‘reading’ modernity, pol-

itics and the novel together, this survey compiles a running commentary of

texts that constitute one possible canon of the Turkish novel.

1

Most of these

works still await translation into English. Where translations are available or

forthcoming, the English title appears before the Turkish.

When the narrative form of the novel first appeared in Ottoman cities in

the 1860s it confronted other forms of traditional narrative that had been in

1 The criteria for this selection aretextsofaesthetic merit that establish or subvert dominant

ideologies, introduce influential changes in narrative form or structure and/or introduce

influential changes in content, character and subject matter.

472

The novel in Turkish

existence for centuries such as mystical verse romances (mesnevi) and oral epics

(destan), the Karag

¨

oz shadow play and meddah storyteller improvisations, Turk-

ish commedia dell’arte (orta oyunu) and minstrel (

ˆ

as¸ık) tales, as well as Qur’anic

and sufic parables. These traditional forms have influenced the genre of the

novel in Turkish to the present day. After an incubatory period of translations

from the French, Ottoman novel writing targeted an urban readership and

was influenced by romantic and realist genres often concerned with social and

ethical issues. Debates until the turn of the century revolved around whether

fiction should concentrate on the aesthetic (‘art for art’s sake’) or have a social,

didactic purpose. In either case, the novel articulated social representations

that were clearly vehicles of modernisation and self-reflection for members of

Ottoman society.

In the late nineteenth century, Ottoman novels appeared in serial in daily

papers as authors sought to entertain, educate or warn the populace through

consciousness raising about social issues. By the early 1910s, the novel became

overtly politicised and was used as a vehicle for intellectual debates con-

cerning state and society. Novelists were also often journalists, politicians,

poets and historians (even today, authors in Turkey are rarely bound to a

single genre). Increasingly, the novel was used as a didactic tool for matters

of poverty, education and the social position of women. In the 1920s and

1930s, the Republican novel was used as a vehicle of nationalisation through

the early decades of the nation-state before giving way (with ever-increasing

literacy rates) in the 1950s and 1960s to a focus on Anatolian social conscious-

ness and the plight of the villager. The attention of authors and their works

moved from the city to the countryside. Ideology played as significant a role

as aesthetics (with major exceptions) in much canonised literature. In the

1970s, however, the concentration on collective, national problems and real-

ities gave way to individual concerns that included feminism, marginalised

voices and victims of state violence. This trend grew even stronger towards

the end of the century as authors revisited modernising projects with irony

and even indifference. Future-oriented movements for progress had reached

an impasse, and after the 1980 military coup, the focus on national realities

turned to fantasy, the imagination, pre-national Ottoman history and, gen-

erally, to an emphasis on form and aesthetic style over content and social

engagement. Currently, the novel in Turkish appears to be working to cap-

ture the broadest possible spectrum of content and form as novelists and their

publishers proliferate. Nothing is sacred to the youngest generation of artists,

and the novel is the art form that is establishing this axiom in the wake of the

‘Turkish Nobel’.

473