Hughes M.P., Hoettges K.F. (Eds.) Microengineering in Biotechnology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

l

The characteristic times to polarize the membrane from the

outside or the inside are well separated in the spectrum.

l

The resulting forces on the particles are larger due to the

Clausius–Mausotti factor but also because larger electric fields

can be applied without generating heating and convective

flows.

l

Positive and negative DEP can both be induced for different

excitation frequencies.

In AC electrokinetic techniques, measurement or separation are

based on the cell motile response to the electric field and thus

uncontrolled pressure or thermally induced flow (and for smaller

particles Brownian motion) can be considered as noise. For cell

sized particles the observable measurement noise in terms of

Brownian motion can be neglected at room temperature and

clearly does not depend on the liquid conductivity.

In ROT, other sources of measurement uncertainty exist,

although not directly related to solution conductivity. Rotation

rate can be influenced by adhesion between the cell and substrate

or by dipole–dipole interactions of nearby cells. At low frequency,

ROT measurements are also complicated by electroosmosis effects

whereby the electric field rotates the double layer and hence the

fluid around the particle.

4.4.2. AC Dielectric

Spectroscopy

In AC dielectric spectroscopy, it is more difficult to answer the

question of medium composition based only on the electrical prop-

erties of the sample because the detection circuit plays an important

role in the determination of the sensitivity of the instrument.

Although a low conductivity medium increases the separation

between the two Maxwell-Wagner dispersions in the spectrum

as shown in Fig. 7.10, the resistance of the detection volume

could well reach the M range. This has number of important

consequences:

l

Higher Johnson noise is expected for low conductivity media.

l

Measurement in the MHz range circuits for high impedance

values are difficult to implement; the electronic and sensor are

much more sensitive to parasitic capacitances.

l

The fraction of conductive current in the system is significantly

reduced whereas the dielectric current increases.

l

To evaluate the total drop in permittivity in a low conductivity

medium, data have to be acquired over a frequency band about

twice as broad to find the low and high frequency values of the

suspension permittivity and conductivity.

l

If the cell to be measured is only present in the measurement

electric field for a few milliseconds, then measurements done

at the lower end of the frequency spectrum will be not have

time to reach equilibrium.

166 Gawad et al.

This comparison between the two approaches seems to indicate

that for AC dielectric spectroscopy, using low conductivities is not

as beneficial as it is in the case of AC electrokinetics.

5. Cell

Manipulation in

Streams

Isolation and positioning of cells in a microfluidic channel by means

of micromanipulation is essential if one is to obtain consistent results

from the device. To reproducibly measure the particle electrical

properties the system must be able to transport the sample solution

precisely to and through specific locations within the chip. By redu-

cing the fluidic channel dimensions, sequential tracking of each

particle passing through the system detection area is made possible.

The flow rate should be held constant over the duration of the

experiment. Accurate speed control and the option to stop or

reverse the flow are desirable functionalities and are relatively

easy to implement using external pressure or flow controllers. By

varying the cross-section of the flow channel consecutive system,

components (e.g., DEP focusing, impedance detection, sorting)

can be integrated along the pathway that the cells take through the

device, each requiring locally different flow and particle speeds.

A number of liquid pumping mechanisms applicable to micro-

systems are described in the literature, which can be separated into

bulk and surface effects. Pressure-driven flow (PDF) is the simplest

implementation for bulk techniques. The driving pressure can be

generated outside of the chip with pumps or pressure regulators

connected by short lengths of small bore tubing to minimize the

compliance of the fluidics of the system as well as maintain sufficient

flow in the sample supply tube to minimize sedimentation effects. A

simple and precise method consist of priming the system and adjust-

ing the height of a water column either up-stream or down-stream

of the chip. Other techniques have been developed to exert pressure

directly on the liquid inside the chip using piezoelectric pumping

(35), centrifugal force (36), or thermal expansion (37).

Microfabricated chips allow the use of negative dielectrophor-

esis (nDEP) as a method to control the trajectories of particles and

cells within the fluidic microchannel. Pairs of planar, overlapped

top and bottom electrode strips are used to produce high electric

field gradients within the liquid. The resulting force on the particle

is proportional to the gradient of the electric field intensity squared

and to the particle polarizability. In nDEP particles tend to move

toward regions of lower electric field intensity. The electrodes are

designed with a defined angle to the flow direction (Fig. 7.11).

When entering the locally generated electric field, the particles

moving under the influence of the PDF are subject to the nDEP

Impedance Spectroscopy, Optical Analysis of Single Biological Cells 167

force acting perpendicular to the electrode strips. The Stokes force,

from the fluid, can be separated into two components. The first,

parallel to the electrodes, tends to move the particles along the

electrodes edge. The second, perpendicular to the strip electrode,

tends to push the particle into the electric field gradient and oppose

the DEP force until the particle arrives at an equilibrium position a

certain distance from the electrode edge. If the Stokes force is too

large and force equilibrium is not reached, the particle will enter the

electric field deeper and potentially cross the nDEP barrier.

A discussion of the nDEP and Stokes force on a particle as a

function of the barrier angle to the fluid flow is given by Du¨rr

et al.(38) and Schnelle et al. (39), using the expressions

F

DEP

¼

27

32

p

2

"

1

Re½

~

KR

3

U

2

rms

h

3

; [13]

F

Stokes

¼ 6pRv: [14]

The particles are deflected by the barrier for F

DEP

4

F

Stokes

sin ,

which gives a maximal speed v

max

Fig. 7.11. Schematic of the chip bottom half structure showing the different electrodes

functions and the electric and fluidic interface. A number of electrodes are unexploited or

redundant in the impedance spectroscopy design, but can be used in other applications.

168 Gawad et al.

v

max

¼

9p"

1

Re½

~

K

64

R

2

U

2

rms

h

3

sin

; [15]

where R is the particle radius, U

rms

is the root mean square of the

electric voltage applied between the electrodes, and h is the chan-

nel height.

In current chip designs, the fluidic channel is wider in the nDEP

regions (100–200 mm) than in the detection part of the system in

order to reduce the flow speed and applied nDEP electric field. The

nDEP electrode are 8 mm wide, which is a compromise between

limitations of fabrication technology, the need for a high electric

field gradient, and minimization of Joule heating in the channel.

A vertical component of the DEP force is also observed. Its effect

is particularly visible on particles whose trajectories are initially close

to the bottom surface of the channel. As the particles get close to the

bottom electrode edge, they are swiftly pushed upward in the flow

and their speed increases as they enter faster flow lines. As they move

to faster lines, the particles experience a larger Stokes force and enter

the barrier field more deeply and thus end up more centered. The

final particle equilibrium position and particularly its height in the

channel is thus a function of the Stokes, sedimentation, and nDEP

forces. The estimated time constant for this effect is observed for the

acceleration of slow particles as they move from the channel walls to

the central flow axis and is on the order the order of a 100 ms. It

should be in principle similar to what is observed in DEP-FFF (40).

Figure 7.11 shows the layout of a typical microfluidic chip

including a DEP focusing area followed by a pair of measurement

electrodes placed between ground shielding electrodes in a nar-

rower channel section. A set of electrodes is added at the exit of the

measurement channel to allow sorting of the particles toward one

fluidic outlet or the other based on their measured properties (41).

To accommodate different chip fluidic configurations, the

fluidic access to the chip or ‘‘holes’’ are defined on a grid with

the possibility for three inlets and three outlets. Figure 7.12

shows dual inlet and triple inlet configurations illustrating the

flexibility of the fluidic system.

ab

Fig. 7.12. Dual input (a) and sheath flow (b) options demonstrating the flexibility of the fluidic setup for pressure-driven

flow control. (Images courtesy of N. Demierre and U. Seger.)

Impedance Spectroscopy, Optical Analysis of Single Biological Cells 169

6. Chip Fabrication

Process

Several techniques may be used to produce capillary channels in

the micrometer size range, but in order to be able to accurately

position electrodes on opposed channel walls the aligned sandwich

technique was used.

Glass substrates were used (100 mm in diameter and 700 mm

thick, Schott-Guinchard, Switzerland). The wafers are optically

polished to l/10 for Ø 5 mm and the surface roughness is speci-

fied below 5 A

˚

.

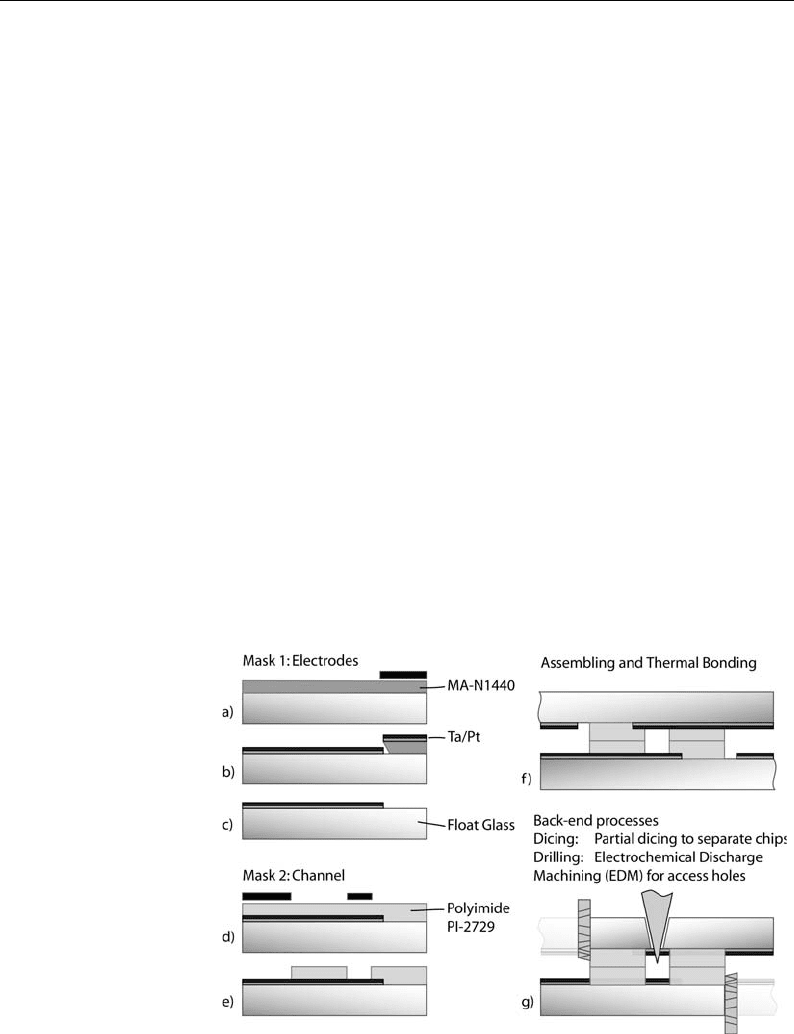

The first deposited layer consists of a thin metal film structure

which is patterned by lift-off using either a reversible photoresist

the AZ-5214 (Clariant) or the ma-N1440 (micro resist technol-

ogy) which does not require an inversion bake (Fig. 7.13a). The

sputtered electrode material consists of tantalum or titanium

(20 nm), as an adhesion layer, and platinum (200 nm) as the active

electrode material (Fig. 7.13b). Both layers were sputtered in

vacuum using a Balzers 450. The deposition rate is set to

0.3 nm s

–1

. Lift-off is done in an ultrasonic acetone bath at

25C, followed by an isopropanol rinse (Fig. 7.13c).

A thick photosensitive polyimide precursor (PI 2729,

Dupont) is used to define the channels. It is spun over the pat-

terned electrodes at a final speed of 4,000 rpm. A preliminary

Fig. 7.13. Process flow for the microfluidic chip. (a–c) Patterning of the microelectrodes

by lift-off. (d–e) Patterning of channel walls with photosensitive polyimide precursor.

(f) Sealing of the channels by flip-chip alignment of the patterned wafer structures and

thermal bonding. (g) Double side partial dicing to separate the chips and provide

electrode contact access. Electrochemical discharge machining is used to open the

access holes.

170 Gawad et al.

adhesion promoter dipping (VM-651, Dupont) is used to prevent

edge detachment of the polyimide layer at development. A soft

bake step of 5 min at 60C followed by a 5 min at 100Cis

performed prior to the layer exposure. Photolithography is done

in hard contact mode and the exposure parameters are 40 s at 10

mW cm

–2

(MA-6, Karl-Suss, Fig. 7.13d). The polyimide devel-

opment process (Fig. 7.13e) is repeated three times in a cycle of

three consecutive baths of 100% developer (DE6180, Dupont),

50–50% developer and rinse mixture and 100% rinse (RI9180,

Dupont), 30 s in each bath and maintaining constant agitation.

A final rinse is performed in a fresh rinse solution and development

is checked optically. As two identical wafers will be put face-to-face

to build a complete chip, the polyimide layer on each chip repre-

sents half of the final channel height.

The alignment of the two facing wafers is performed with a

bond aligner (BA-6, Karl-Suss), with an estimated alignment

precision of 2–3 mm. The thermal bonding (SB-6, Karl-Suss,

Fig. 7.13f) of the facing polyimide layers is done under a tool

pressure of 5 bars and by ramping the temperature to 200C

for a bake of 30 min in air and followed by 300CinN

2

for 1h

(Fig. 7.14). The first bake is performed in order to degrade the

photo-package with oxygen, as it is known to migrate to the

polyimide surface and prevent adhesion between the two layers.

At higher temperature, an inert atmosphere is maintained to pre-

vent oxidation of the polyimide, which is otherwise observed as

darkening of the polymer layer after bonding.

Another aspect of the polyimide–polyimide bonding process is

the significant degassing and consequent volume reduction that

occurs during curing. The thickness of the layer after the thermal

Fig. 7.14. Two bonded wafers containing 21 chips. Dicing and drilling are then performed

to obtain individual functional devices.

Impedance Spectroscopy, Optical Analysis of Single Biological Cells 171

bonding procedure is only 50% of the originally spun precursor.

Degassing is responsible for the formation of bubbles at the inter-

face between the polyimide layers. To allow these byproducts to

vent, a venting grid is used around the fluidic channels. The design

of this grid is such that measurement and DEP electrodes are

covered by polyimide everywhere except in the channel and elec-

trical contact areas. The final operations consist of the back-end

processes performed in a grey room and include partial chip dicing

in order to access the electrode contacts on each side of the chip

and electrochemical discharge machining to drill the fluidic access

holes (Fig. 7.13 g) (42).

The electrochemical access hole drilling process is shown in

Fig. 7.15. With the wafer scale polyimide bonding, this operation

represents one of the most critical step in the chip manufacturing

a

b

Fig. 7.15. Principle of glass electrochemical etching (a) and view of a microfluidic chip

with electrochemically etched access holes (b). The chip is placed in a 30% NaOH

solution. Electrical discharges are produced at a tip of a steel electrode which etches the

glass at a rate of 20 mms

–1

.

172 Gawad et al.

as glass debris and other particles can enter and obstruct the

microfluidic channels. Ultrasonic and PDF cleaning using differ-

ent liquid viscosities can be used in cases where debris has entered

the channels and generally permits 100% recovery of the chips.

Alternative techniques would be required in order to indus-

trialize this process, allowing mass production of such devices. A

possible approach would be to define the channel walls on a single

wafer and to drill holes on the second prior to bonding.

6.1. Experimental

Setup

A fluidic block composed of two mechanical parts is used to hold

the chip in the center of the amplification electronics circuit board

Fig. 7.16. The bottom part of the block is screwed to the printed

circuit board and allows for precise placement of the chip. Two

interface connectors each with 15 gold plated spring contacts

(Samtec, 1 mm pitch) are used to contact the top and bottom of

the platinum electrodes. Compared to other techniques, such as

wire bonding or soldering, replacing the chip in the setup is very

fast, requires no tools, and gives excellent reproducibility.

The top part is made of PEEK, which is resistant to solvents

and bleach (Fig. 7.17). It provides L-shaped conduits to the chip

fluidic apertures and the top side electrical connections to the chip.

The fluidic contact is made watertight using miniature o-rings.

The tubing connection to the fluidic block uses standard NPT 28

1/16 connectors. Additionally, an aperture is made in the center

of the top block for non-fluorescent illumination of the chip.

Fig. 7.16. The chip is placed in the PEEK electro-fluidic interconnection block. The top

and bottom electrical connections are provided by two rows of 15 spring-loaded

contacts. Optical access and transmissive illumination are provided through holes in

the printed circuit board and block.

Impedance Spectroscopy, Optical Analysis of Single Biological Cells 173

A rotary valve selects the different washing or priming liquids,

which are contained in pressurized bottles. Additionally, a motor-

ized syringe pump is used for fast purging of the whole line with

high pressure and proved very useful in case of channel clogging.

The tubing inner diameter in the sample path is 120 mm, while it is

1 mm for the purging and washing liquids. The sample holder

tubing to the fluidic block is made as short as possible in order to

avoid cell sedimentation in the tubing. The holder supports stan-

dard 5 ml falcon tubes and provides sample agitation functionality to

avoid sedimentation as well as optional temperature control. A valve is

placed just before the fluidic block to select between cleaning liquid

and sample. An inlet-side waste provides for a way to quickly purge

the entry lines without having to remove the chip. Pressure control of

the sample tube is provided by a high-precision pressure regulator

(Marsh-Bellofram), with full scale pressure of 10 psi (0.7 bar), for ten

turns. The regulator allows precise control of the fluid flow and is

sufficient to stop the flow and particles even in the smallest part of the

microchannel. The time constant of the system fluidics is estimated

to be below 0.2 s. The height and level of the liquid in the

collection vials is set so as to produce a small back-flow when

atmospheric pressure is applied on the sample.

7. Measurements

and Results

The primary aim of this section is to demonstrate that such a

system can discriminate particles according to their dielectric and

optical properties. We illustrate the efficacy of the system with the

Fig. 7.17. Fluidic setup. The different washing liquids are either volume or pressure

driven. The desired liquid or sample can be directed to the fluidic block through rotary

valves. Miniature o-rings provide quick and water-tight fluidic connection to the chip.

Waste vials are available before or after the chip for tube purging and fast sample

injection.

174 Gawad et al.

example of algae species discrimination. However, to test the

system sensitivity, a number of preliminary experiments based on

simple non-biological models are regularly performed. These steps

are useful in defining or verifying a number of measurement para-

meters such as particles’ flow speed, filters, or gain settings, which

influence the measurements.

The calibration test is performed on the impedance spectro-

scopy instrument using beads of three different sizes, with diameters

of 4.0 mm, and 6.0 mm (Duke scientific), and 5.14 mm (Molecular

probes), which are mixed in the same sample tube. In Fig. 7.18,

they are designated as 4, 5.14, and 6 mm beads. The coefficient of

variation (CV) of the particles measured with a commercial FACS,

the microfabricated impedance chip and those given by the bead

manufacturers are summarized in Table 7.1.

Sub-micron size differentiation using calibrated polystyrene

beads is thus easily achieved with such a system.

A number of measurements have previously demonstrated the

application of such a system in the field of haematology and

immunology. Published work also shows differentiation between

red blood cells and red blood cell ghosts fixed with glutaraldehyde

at various concentrations (43).

More recently, preliminary data using the impedance spectro-

scopy flow cytometry system shows the possibility of discrimina-

tion between neutrophils (granular, 12–15 mm diameter, multi-

lobed nucleus), lymphocytes (5–10 mm, large nucleus), and

monocytes (12–18 mm, U-shaped nucleus). Lymphocytes can be

Fig. 7.18. Size-calibrated bead data as measured in PBS at 3 MHz using the integrated

impedance sensor. Simple analysis of the signal shape of the dots outside the three main

clouds showed they were due to doublets and were discarded for CV calculations.

Impedance Spectroscopy, Optical Analysis of Single Biological Cells 175