Houze Robert A., Jr. Cloud Dynamics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1.2 Cloud Types Identified Visually 19

wider area). Or it may be the upper-level leading or trailing canopy of a nimbo-

stratus cloud. A common form of cirrostratus is the leading canopy of a frontal

cloud system (as can be seen in satellite pictures such as those shown below in

Sec. 1.3.3). A common feature of cirrostratus is the halo produced as the sun

shines through the layer of ice particles (Fig. 1.17).

1.2.5 Orographic Clouds

Air moving over or around hilly or mountainous terrain often influences cloud

formation. Many of the basic cloud genera and species already described can be

forced, triggered, or enhanced orographically. For example, mountain ranges are

typically preferred locations for fog, stratus, stratocumulus, cumulus, and cumu-

lonimbus, and they affect the structure and precipitation of nimbostratus clouds

associated with weather systems such as fronts. Valleys between mountains often

favor fog occurrence. In addition to the modification of the cloud types that may

occur anywhere, there are cloud forms that are uniquely associated with topogra-

phy, and Chapter 12 is devoted to the dynamics of these truly orographic clouds.

As mentioned above, the lenticularis species describes some of these cloud forms.

Lenticular clouds form when air flows over a mountain. If the mountain is in the

form of an isolated peak, a cap cloud may form directly on the top of the mountain

(Fig.

1.18).18

Lenticular clouds may also form downwind of the peak. An example

of this phenomenon is shown in Fig. 1.19, where the lenticular cloud downwind of

the peak has the shape of a horseshoe.

For

reasons to be discussed in Chapter 12, the lenticular clouds in Fig. 1.18and

1.19are a type of wave cloud. If the wave clouds are associated with a long quasi-

two-dimensional mountain ridge rather than an isolated peak, the wave clouds

may be in the form oflong cloud bands. Figure 1.20 shows wave clouds associated

with the Continental Divide of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. The main ridge

18 These disk-shaped clouds over the tops of mountains appear to account for many reports of

"flying saucers." The first modern report of a flying saucer

(1947)

was made over Mt. Rainier,

Washington, where spectacular displays of lenticular clouds over the summit are sometimes seen.

Figure 1.16 Cirrus spissatus with virga (i.e., precipitation falling out of the cloud but not reaching

the ground). Seattle, Washington. (Photo by Steven Businger.)

Figure 1.17 Cirrostratus with halo. Seattle, Washington. (Photo by Arthur

L. Rangno.)

Figure 1.18 Cap cloud over Mount Rainier, Washington. (Photo by Peter Thomas.)

Figure 1.19 Horseshoe-shaped cloud (Turusi) in lee of Mt. Fuji, Japan. (Photo taken in

1930 by

Masanao Abe.)

Figure 1.20 Looking upwind at a lee-wave cloud band (foreground) in Boulder, Colorado. Stacks

of lenticular clouds give the band a bumpy appearance. In the distance is a wave cloud band capping

the Continental Divide, which is the main orographic barrier. The mountains in the foreground, which

appear larger in the photo, are actually smaller foothills. (Photo by Dale R. Durran.)

20 1 Identification of Clouds

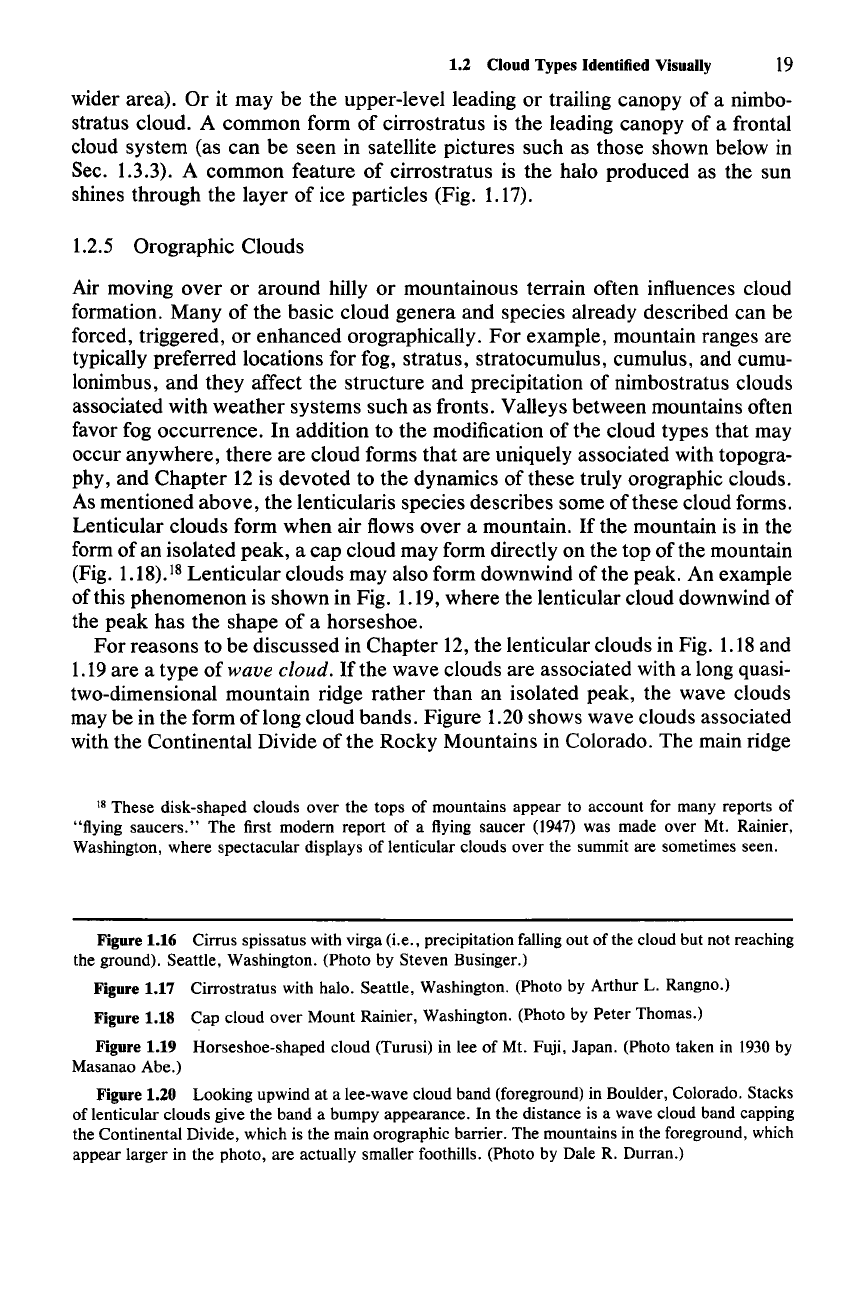

Figure 1.21 Looking upwind at a lenticular wave-cloud band (foreground) forming in the lee of the

Continental Divide, which is in the distance, far beyond the foothill mountains seen in the foreground.

Boulder, Colorado. (Photo by Dale R. Durran.)

is in the background, and a wave cloud capping the ridge can be seen in the

distance. The mountains in the foreground are actually smaller foothills. Over

these foothills is a wave-cloud band. Large stacks of lenticular clouds can be seen

at several locations along the band. Sometimes the wave-cloud bands in the lee of

a ridge can have the appearance of a smooth bar (Fig. 1.21). Often a series of

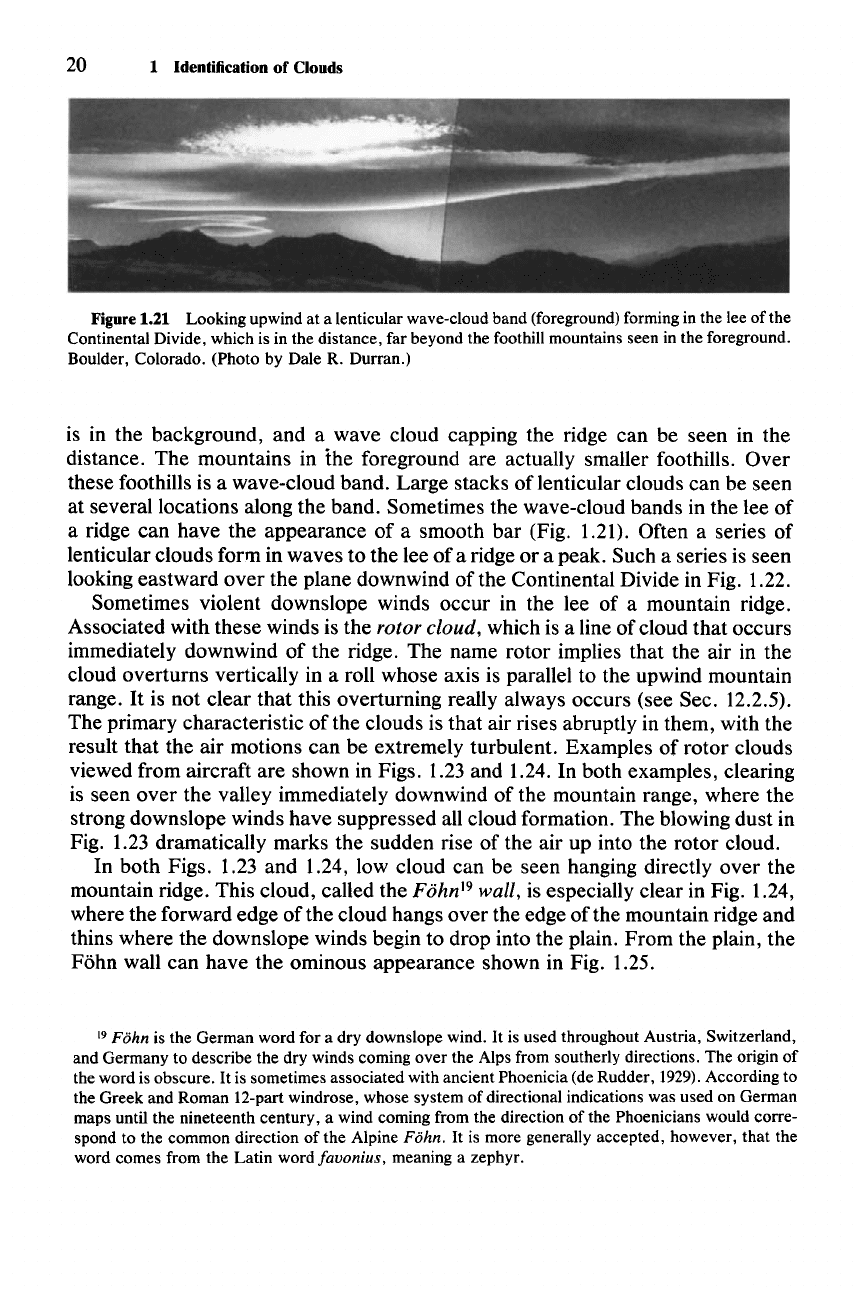

lenticular clouds form in waves to the lee of a ridge or a peak. Such a series is seen

looking eastward over the plane downwind of the Continental Divide in Fig. 1.22.

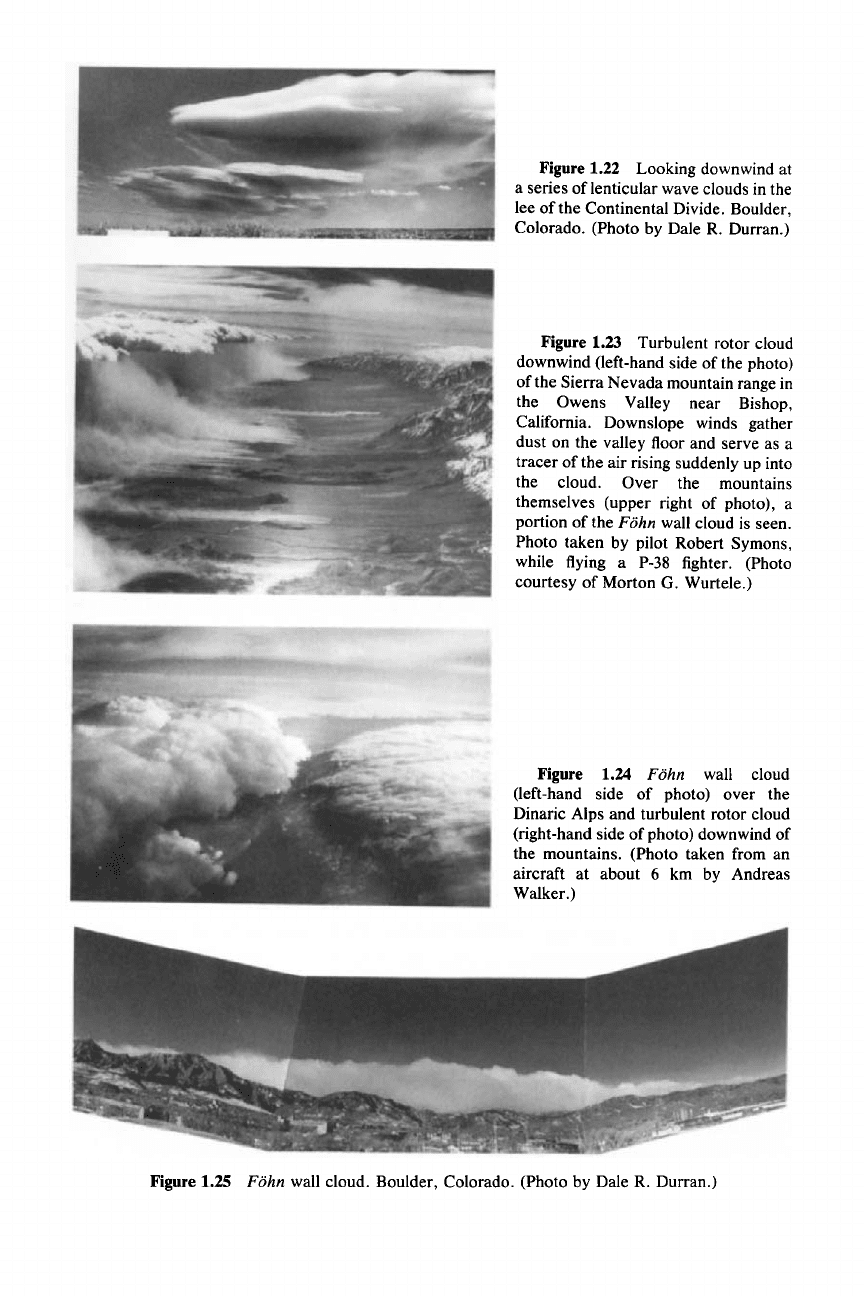

Sometimes violent downslope winds occur in the lee of a mountain ridge.

Associated with these winds is the

rotor cloud, which is a line of cloud that occurs

immediately downwind of the ridge. The name rotor implies that the air in the

cloud overturns vertically in a roll whose axis is parallel to the upwind mountain

range.

It

is not clear that this overturning really always occurs (see Sec. 12.2.5).

The primary characteristic of the clouds is that air rises abruptly in them, with the

result that the air motions can be extremely turbulent. Examples of rotor clouds

viewed from aircraft are shown in Figs. 1.23 and 1.24. In both examples, clearing

is seen over the valley immediately downwind of the mountain range, where the

strong downslope winds have suppressed all cloud formation. The blowing dust in

Fig. 1.23 dramatically marks the sudden rise of the air up into the rotor cloud.

In both Figs. 1.23 and 1.24, low cloud can be seen hanging directly over the

mountain ridge. This cloud, called the

Fohn'? wall, is especially clear in Fig. 1.24,

where the forward edge of the cloud hangs over the edge of the mountain ridge and

thins where the downslope winds begin to drop into the plain. From the plain, the

Fohn wall can have the ominous appearance shown in Fig. 1.25.

19 Fohn is the German word for a dry downslope wind. It is used throughout Austria, Switzerland,

and Germany to describe the dry winds coming over the Alps from southerly directions. The origin of

the word is obscure.

It

is sometimes associated with ancient Phoenicia (de Rudder, 1929).According to

the Greek and Roman 12-part windrose, whose system of directional indications was used on German

maps until the nineteenth century, a wind coming from the direction of the Phoenicians would corre-

spond to the common direction of the Alpine

Fohn.

It

is more generally accepted, however, that the

word comes from the Latin wordfavonius, meaning a zephyr.

Figure 1.22 Looking downwind at

a series of lenticular wave clouds in the

lee

ofthe

Continental Divide. Boulder,

Colorado. (Photo by Dale R. Durran.)

Figure 1.23 Turbulent rotor cloud

downwind (left-hand side of the photo)

of the Sierra Nevada mountain range in

the Owens Valley near Bishop,

California. Downslope winds gather

dust on the valley floor and serve as a

tracer of the air rising suddenly up into

the cloud. Over the mountains

themselves (upper right of photo), a

portion of the Fohn wall cloud is seen.

Photo taken by pilot Robert Symons,

while flying a P-38 fighter. (Photo

courtesy of Morton G. Wurtele.)

Figure 1.24 Fohn wall cloud

(left-hand side of photo) over the

Dinaric Alps and turbulent rotor cloud

(right-hand side of photo) downwind of

the mountains. (Photo taken from an

aircraft at about 6 km by Andreas

Walker.)

Figure 1.25 Fohn wall cloud. Boulder, Colorado. (Photo by Dale R. Durran.)

22 1 Identification of Clouds

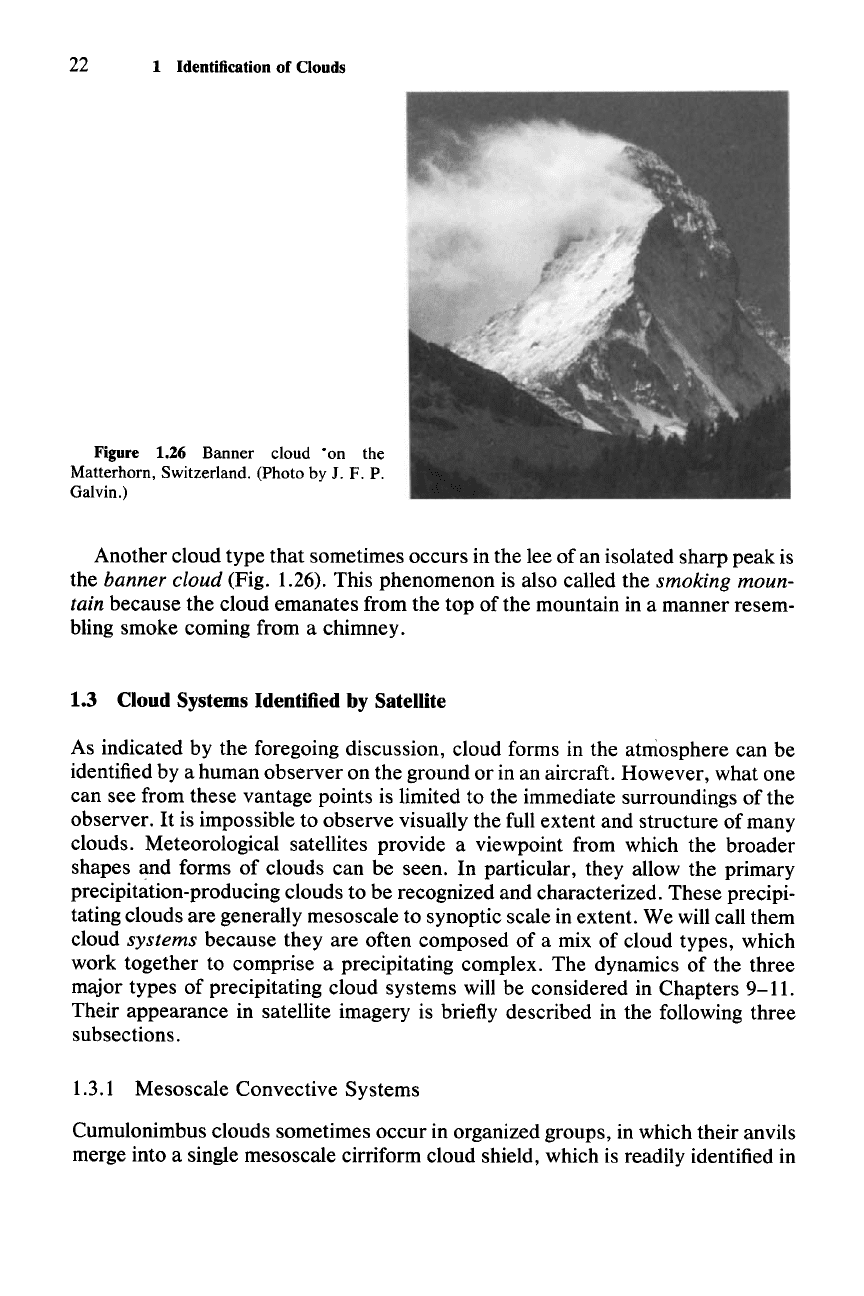

Figure 1.26 Banner cloud "on the

Matterhorn, Switzerland. (Photo

by J. F. P.

Galvin.)

Another cloud type that sometimes occurs in the lee of an isolated sharp peak is

the banner cloud (Fig. 1.26). This phenomenon is also called the smoking moun-

tain because the cloud emanates from the top of the mountain in a manner resem-

bling smoke coming from a chimney.

1.3 Cloud Systems Identified by Satellite

As indicated by the foregoing discussion, cloud forms in the atmosphere can be

identified by a human observer on the ground or in an aircraft. However, what one

can see from these vantage points is limited to the immediate surroundings of the

observer.

It

is impossible to observe visually the full extent and structure of many

clouds. Meteorological satellites provide a viewpoint from which the broader

shapes and forms of clouds can be seen. In particular, they allow the primary

precipitation-producing clouds to be recognized and characterized. These precipi-

tating clouds are generally mesoscale to synoptic scale in extent. We will call them

cloud systems because they are often composed of a mix of cloud types, which

work together to comprise a precipitating complex. The dynamics of the three

major types of precipitating cloud systems will be considered in Chapters

9-11.

Their appearance in satellite imagery is briefly described in the following three

subsections.

1.3.1 Mesoscale Convective Systems

Cumulonimbus clouds sometimes occur in organized groups, in which their anvils

merge into a single mesoscale cirriform cloud shield, which is readily identified in

1.3 Cloud Systems Identified by Satellite 23

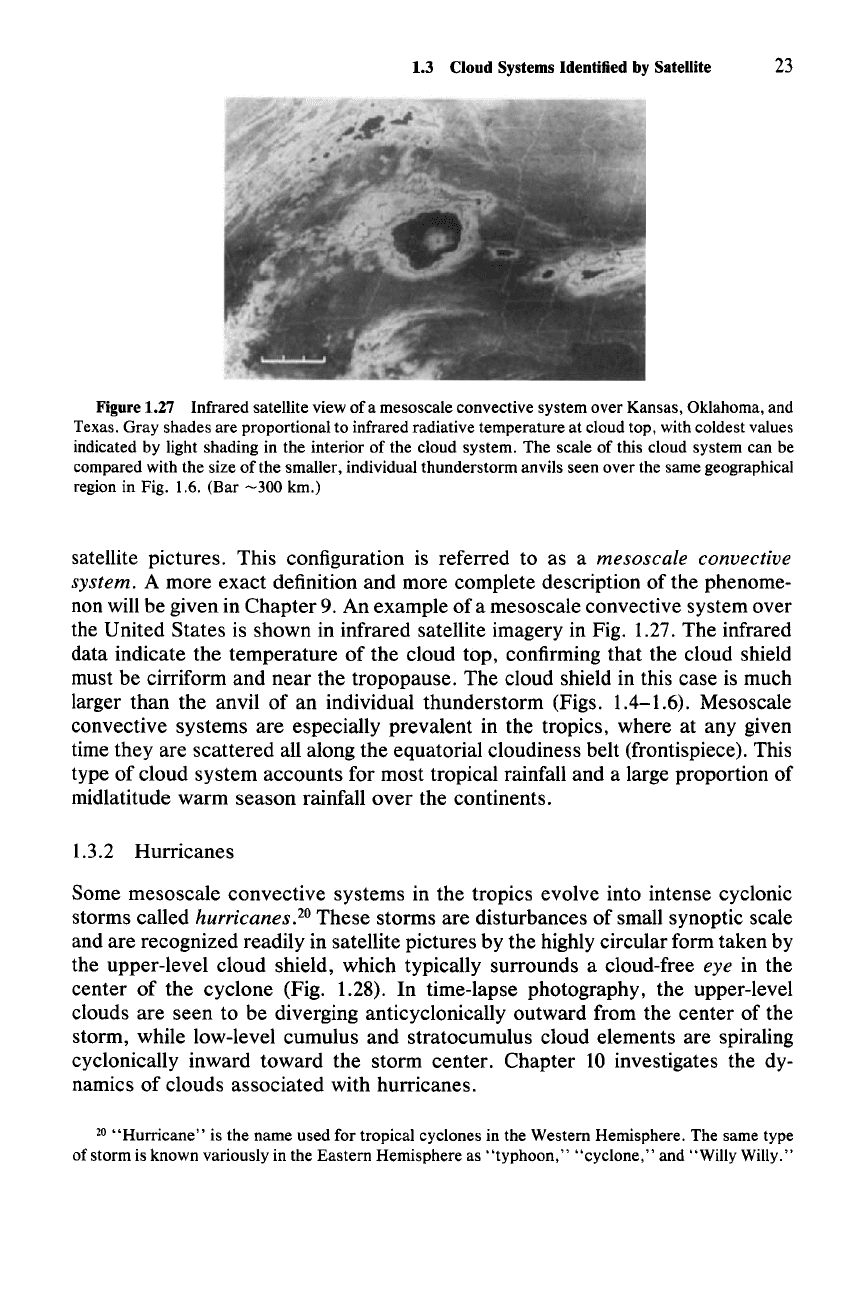

Figure 1.27 Infrared satellite view of a mesoscale convective system over Kansas, Oklahoma, and

Texas. Gray shades are proportional to infrared radiative temperature at cloud top, with coldest values

indicated by light shading in the interior of the cloud system. The scale of this cloud system can be

compared with the size

ofthe

smaller, individual thunderstorm anvils seen over the same geographical

region in Fig. 1.6. (Bar

-300

km.)

satellite pictures. This configuration is referred to as a mesoscale convective

system.

A more exact definition and more complete description of the phenome-

non will be given in Chapter 9. An example

of

a mesoscale convective system over

the United States is shown in infrared satellite imagery in Fig. 1.27. The infrared

data indicate the temperature

of

the cloud top, confirming that the cloud shield

must be cirriform and near the tropopause. The cloud shield in this case is much

larger than the anvil

of

an individual thunderstorm (Figs. 1.4-1.6). Mesoscale

convective systems are especially prevalent in the tropics, where at any given

time they are scattered all along the equatorial cloudiness belt (frontispiece). This

type of cloud system accounts for most tropical rainfall and a large proportion of

midlatitude warm season rainfall

over

the continents.

1.3.2 Hurricanes

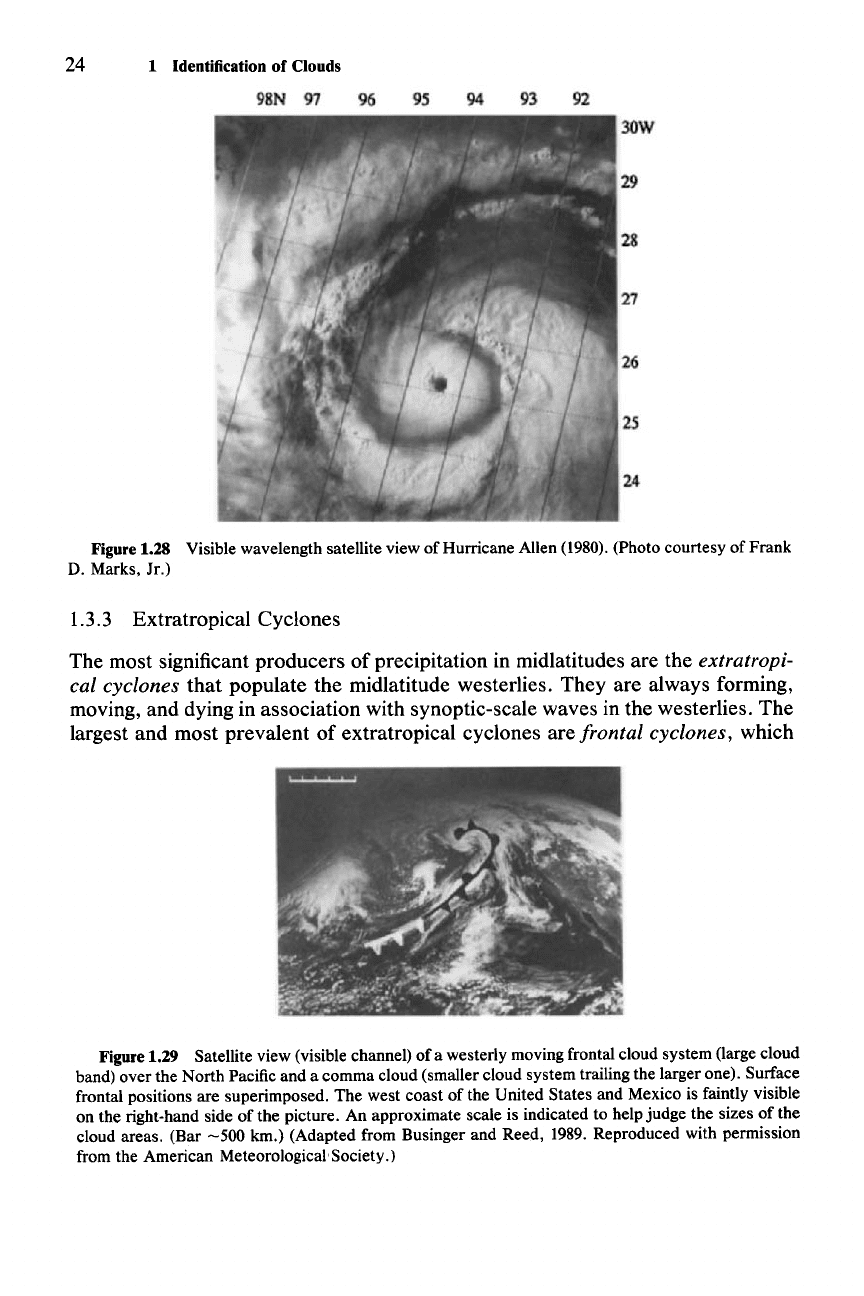

Some mesoscale convective systems in the tropics evolve into intense cyclonic

storms called

hurricanes.20 These storms are disturbances of small synoptic scale

and are recognized readily in satellite pictures by the highly circular form taken by

the upper-level cloud shield, which typically surrounds a cloud-free

eye in the

center of the cyclone (Fig. 1.28). In time-lapse photography, the upper-level

clouds are seen to be diverging anticyclonically outward from the center of the

storm, while low-level cumulus and stratocumulus cloud elements are spiraling

cyclonically inward toward the storm center. Chapter 10 investigates the dy-

namics of clouds associated with hurricanes.

20

"Hurricane"

is the name used for tropical cyclones in the Western Hemisphere. The same type

of storm is known variously in the Eastern Hemisphere as

"typhoon,"

"cyclone," and "Willy Willy."

24 1 Identification of Clouds

Figure 1.28 Visible wavelength satellite view of Hurricane Allen (1980). (Photo courtesy of Frank

D. Marks,

Ir.)

1.3.3 Extratropical Cyclones

The most significant producers of precipitation in midlatitudes are the extratropi-

cal cyclones that populate the midlatitude westerlies. They are always forming,

moving, and dying in association with synoptic-scale waves in the westerlies. The

largest and most prevalent of extratropical cyclones are frontal cyclones, which

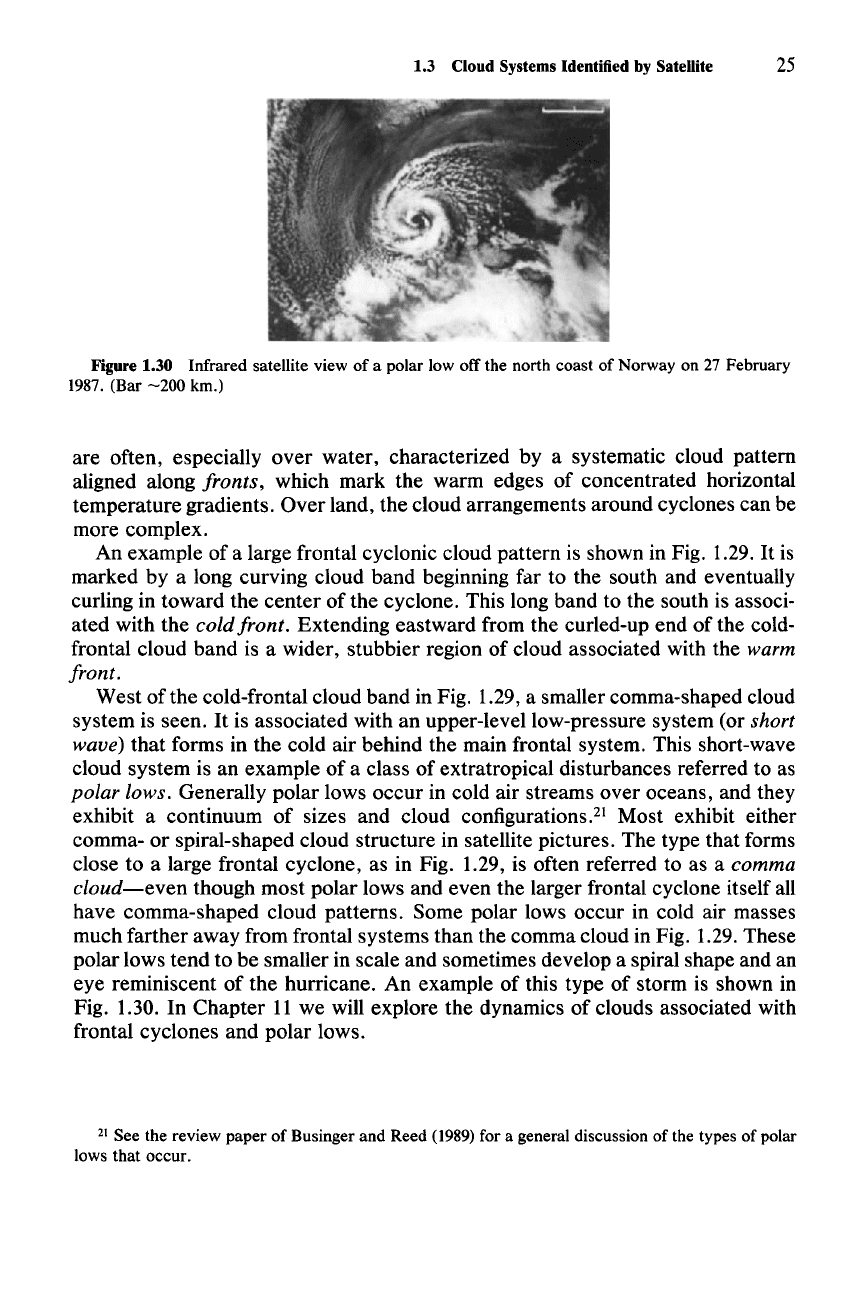

Figure 1.29 Satellite view (visible channel) of a westerly moving frontal cloud system (large cloud

band) over the North Pacific and a comma cloud (smaller cloud system trailing the larger one). Surface

frontal positions are superimposed. The west coast of the United States and Mexico is faintly visible

on the right-hand side of the picture. An approximate scale is indicated to help judge the sizes of the

cloud areas. (Bar

-500

km.) (Adapted from Businger and Reed, 1989. Reproduced with permission

from the American MeteorologicalSociety.)

1.3 Cloud Systems Identified by Satellite 25

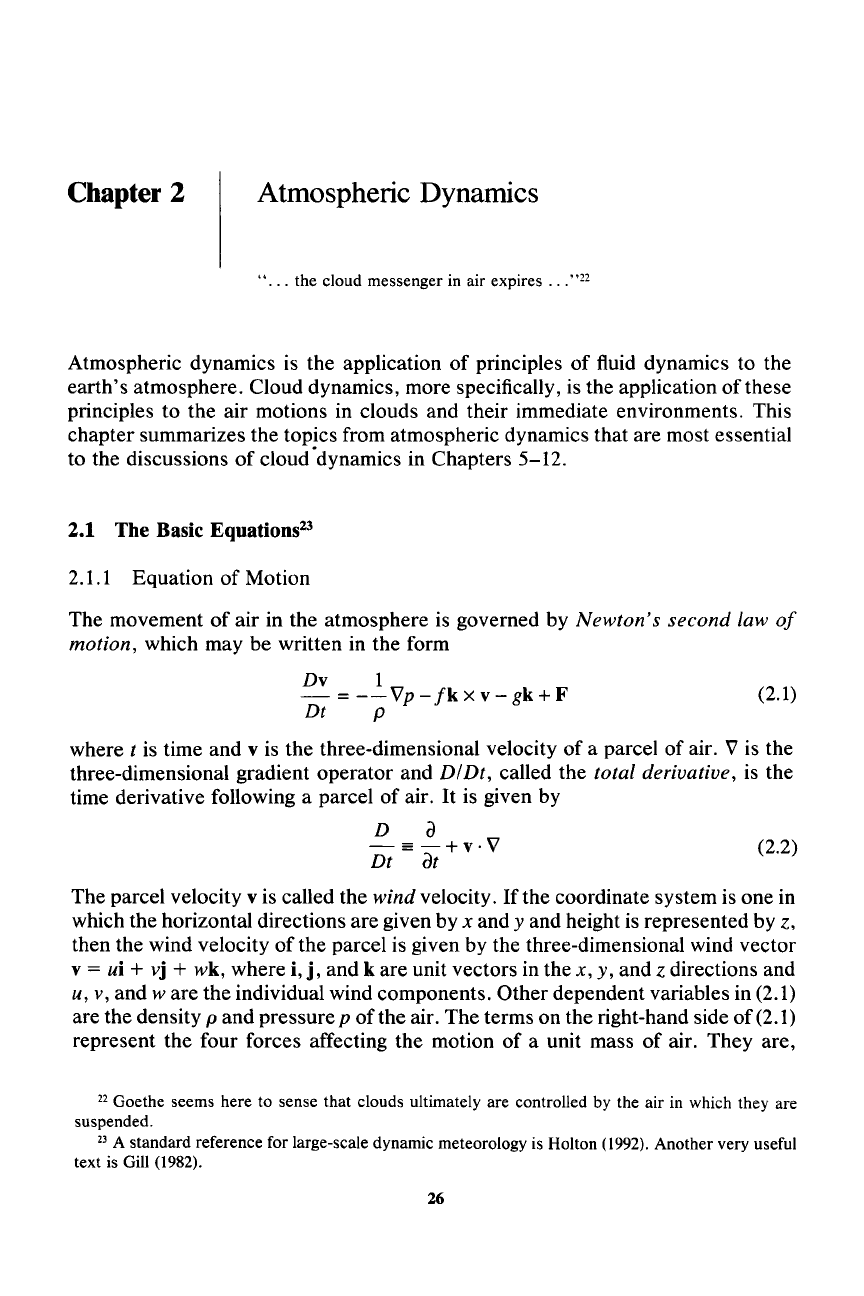

Figure 1.30 Infrared satellite view of a polar low off the north coast of Norway on 27 February

1987. (Bar

-200

km.)

are often, especially over water, characterized by a systematic cloud pattern

aligned along

fronts, which mark the warm edges of concentrated horizontal

temperature gradients. Over land, the cloud arrangements around cyclones can be

more complex.

An example of a large frontal cyclonic cloud pattern is shown in Fig. 1.29.

It

is

marked by a long curving cloud band beginning far to the south and eventually

curling in toward the center of the cyclone. This long band to the south is associ-

ated with the

cold front. Extending eastward from the curled-up end of the cold-

frontal cloud band is a wider, stubbier region of cloud associated with the

warm

front.

West

ofthe

cold-frontal cloud band in Fig. 1.29, a smaller comma-shaped cloud

system is seen.

It

is associated with an upper-level low-pressure system (or short

wave)

that forms in the cold air behind the main frontal system. This short-wave

cloud system is an example of a class of extratropical disturbances referred to as

polar lows. Generally polar lows occur in cold air streams over oceans, and they

exhibit a continuum of sizes and cloud configurations." Most exhibit either

comma- or spiral-shaped cloud structure in satellite pictures. The type that forms

close to a large frontal cyclone, as in Fig. 1.29, is often referred to as a

comma

cloud-even

though most polar lows and even the larger frontal cyclone itself all

have comma-shaped cloud patterns. Some polar lows occur in cold air masses

much farther away from frontal systems than the comma cloud in Fig. 1.29. These

polar lows tend to be smaller in scale and sometimes develop a spiral shape and an

eye reminiscent of the hurricane. An example of this type of storm is shown in

Fig. 1.30. In Chapter

11

we will explore the dynamics of clouds associated with

frontal cyclones and polar lows.

21 See the review paper of Businger and Reed (1989) for a general discussion of the types of polar

lows that occur.

Chapter

2 Atmospheric Dynamics

.....

the cloud messenger in air expires

...

"22

(2.1)

(2.2)

Atmospheric dynamics is the application of principles of fluid dynamics to the

earth's

atmosphere. Cloud dynamics, more specifically, is the application

ofthese

principles to the air motions in clouds and their immediate environments. This

chapter summarizes the topics from atmospheric dynamics that are most essential

to the discussions of cloud ·dynamics in Chapters

5-12.

2.1 The Basic Equations-'

2.1.1 Equation of Motion

The movement

of

air in the atmosphere is governed by

Newton's

second

law

of

motion, which may be written in the form

Dv

1

- =

--Vp-

fk

x

v-

gk+F

Dt P

where

t is time

and

v is the three-dimensional velocity of a parcel of air. V is the

three-dimensional gradient operator and DIDt, called the total derivative, is the

time derivative following a parcel of air.

It

is given by

D a

-=-+v·V

Dt

at

The parcel velocity v is called the wind velocity. If the coordinate system is one in

which the horizontal directions are given by

x and y and height is represented by z,

then the wind velocity of the parcel is given by the three-dimensional wind vector

v

= ui + vj + wk, where i,

j,

and k are unit vectors in the x, y, and z directions and

u, v, and

ware

the individual wind components. Other dependent variables in (2.1)

are the density

p

and

pressure p

of

the air. The terms on the right-hand side of (2.1)

represent the four forces affecting the motion of a unit mass of air. They are,

22 Goethe seems here to sense that clouds ultimately are controlled by the air in which they are

suspended.

23 A standard reference for large-scale dynamic meteorology is Holton (1992). Another very useful

text is Gill (1982).

26

2.1 The Basic Equations 27

respectively, the pressure-gradient, Coriolis, gravitational, and frictional acceler-

ations.

The

quantity g is the magnitude of the gravitational acceleration,

whilefis

the Coriolis parameter

211

sin

<1>,

where

11

is the angular speed of the earth's

rotation and

<I>

is latitude.

2.1.2 Equation of State

The thermodynamic state of dry air is well approximated by the equation

of

state

for an ideal gas, written in the form

(2.3)

(2.6)

where

R

d

is the gas constant for dry air and T is temperature. When air contains

water vapor, this equation is modified to

p=pRdTv (2.4)

where Tv is the virtual temperature, given to a good degree of approximation by

Tv

"" T( 1+

O.61qv)

(2.5)

where qv is the mixing ratio of water vapor in air (mass of water vapor per unit

mass of air).

2.1.3 Thermodynamic Equation

Changes of temperature

of

a parcel of air are governed by the First

Law

of

Thermodynamics, which for an ideal gas may be written as

DT

Dtx .

c

-+p-=H

v Dt Dt

where

if

is the heating rate, c, is the specific heat of dry air at constant volume, T

is temperature, and a is the specific volume

p-I.

The first term on the left of (2.6) is

the rate of change

of

internal energy of the parcel, while the second term is the

rate at which work is done by the parcel on its environment. With the aid of the

equation of state (2.4), the First

Law

(2.6) may be written in the form

DT

Dp .

c

--a-

= H (2.7)

P Dt Dt

where c

p

is the specific heat of dry air at constant pressure.

It

is often preferable to

write the First

Law

in terms of the potential temperature,

(2.8)

where K = R

d

/ c

p

,

R

d

is the gas constant for dry air (the difference between the

specific heats at constant pressure and volume), and

p is a reference pressure,

28 2 Atmospheric Dynamics

usually assumed to be 1000 mb. In terms of

(),

(2.7) takes the simple form

DO

.

-=

'Je

Dt

(2.9)

(2.10)

where

~=:p(~rH

In cloud dynamics,

iI

includes the sum of heating and cooling associated with

phase changes of water, radiation and molecular diffusional processes. Under

adiabatic (isentropic) conditions,

(2.9) reduces to

(2.11)

DO

-=0

Dt

For

cloud dynamics, the form '(2.11) is often not useful, since the latent heat of

phase change and/or radiation may render the in-cloud conditions nonisentropic.

When the only phase changes are associated with condensation and evaporation

of water, the First Law (2.7) can be written as

DT

Dp Dqv

c

--a-=-L--

p Dt Dt Dt

(2.12)

where contributions to the specific heat and specific volume from water vapor and

condensed water have been neglected. With the aid of (2.8), (2.12) can be written

as

(2.13)

DO

L Dqv

=-----

Dt

cpTI

Dt

where qy is the mixing ratio of water vapor (kilograms of water per kilogram of

air),

L is the latent heat of vaporization, and

TI,

called the

Exner

function,

is

defined as

(2.14)

A useful quantity in this case is the

equivalent

potential

temperature

(}e, defined as

the potential temperature a parcel of air would have if all its water vapor was

condensed and the latent heat converted into sensible heat. Integration of (2.13)

shows that, as long as the air is

saturated,

the equivalent potential temperature is

(2.15)

where

qys(T,p) is the

saturation

mixing

ratio, defined as the value of the mixing

ratio when air at temperature

T and pressure p is saturated, and the integral in