Higgins R.A. Engineering Metallurgy: Applied Physical Metallurgy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

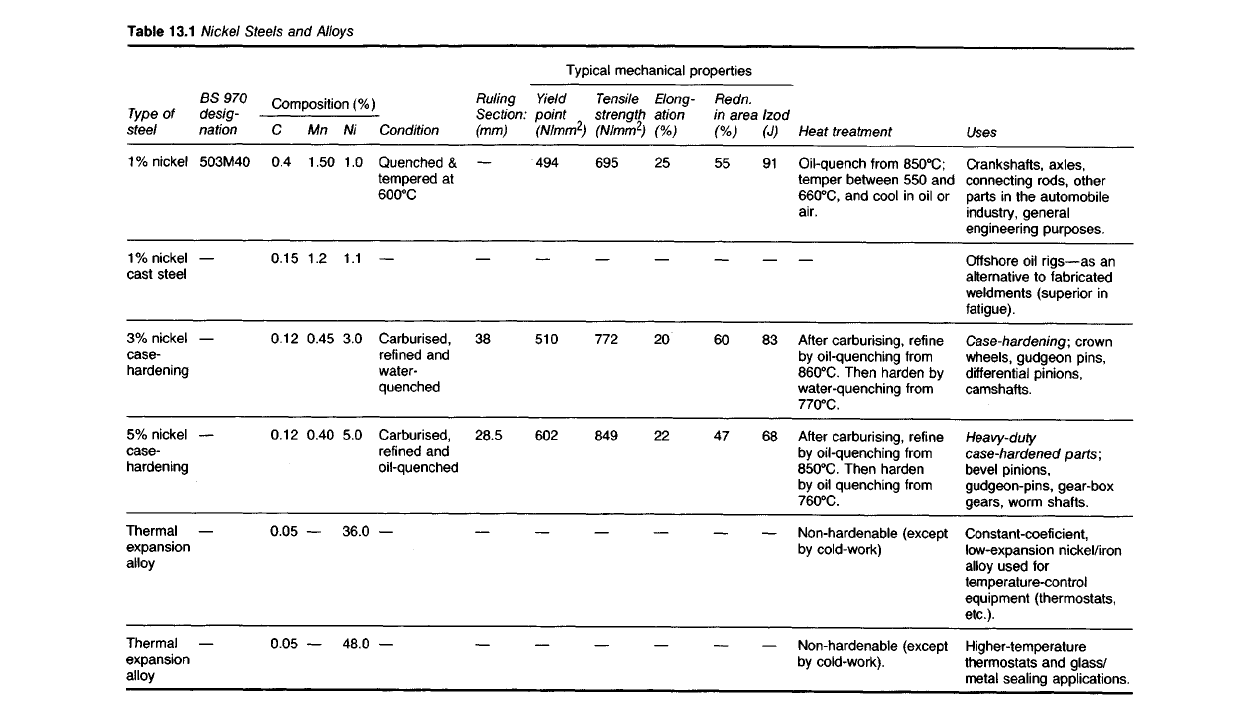

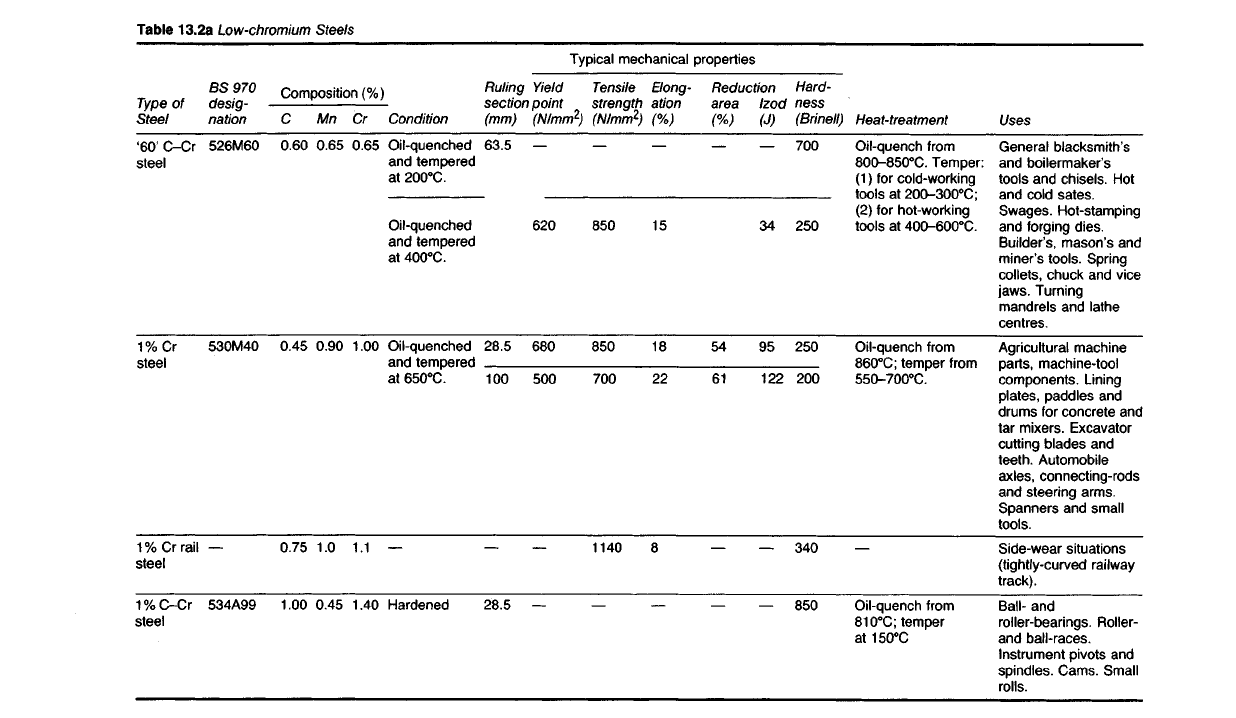

Table

13.1

Nickel

Steels and Alloys

Uses

Crankshafts, axles,

connecting rods, other

parts

in the automobile

industry,

general

engineering purposes.

Offshore

oil rigs—as an

alternative to fabricated

weldments (superior in

fatigue).

Case-hardening;

crown

wheels, gudgeon pins,

differential pinions,

camshafts.

Heavy-duty

case-hardened

parts;

bevel pinions,

gudgeon-pins, gear-box

gears, worm shafts.

Constant-coefi cient,

low-expansion nickel/iron

alloy used for

temperature-control

equipment (thermostats,

etc.).

Higher-temperature

thermostats and glass/

metal

sealing

applications.

Heat treatment

Oil-quench

from

850

0

C;

temper between 550 and

660

0

C,

and cool in oil or

air.

After

carburising, refine

by

oil-quenching

from

860

0

C.

Then

harden by

water-quenching

from

770

0

C.

After

carburising, refine

by

oil-quenching from

850

0

C.

Then harden

by

oil quenching

from

760

0

C.

Non-hardenable (except

by

cold-work)

Non-hardenable (except

by

cold-work).

Typical mechanical properties

Izod

(J)

91

83

68

Redn.

in area

(%)

55

60

47

Elong-

ation

(%)

25

20

22

Tensile

strength

(N/mm

2

)

695

772

849

Yield

point

(N/mm

2

)

494

510

602

Ruling

Section:

(mm)

38

28.5

Composition

(%)

Condition

Quenched &

tempered at

600

0

C

Carburised,

refined

and

water-

quenched

Carburised,

refined and

oil-quenched

Ni

1.0

1.1

3.0

5.0

36.0

48.0

Mn

1.50

1.2

0.45

0.40

C

0.4

0.15

0.12

0.12

0.05

0.05

BS 970

desig-

nation

503M40

Type

of

steel

1% nickel

1% nickel

cast steel

3% nickel

case-

hardening

5% nickel

case-

hardening

Thermal

expansion

alloy

Thermal

expansion

alloy

but these have been largely replaced by nickel-chromium; nickel-molyb-

denum or nickel-chromium-molybdenum steels.

13.25 Nickel reduces the coefficient of thermal expansion of iron-

nickel alloys progressively, until with 36% nickel expansion is extremely

small. Invar' (36Ni; C-less than 0.1) was developed originally for accurate

measuring tapes used in land surveys. In 1920 C. E. Guillaume received

the Nobel Prize for Physics in recognition for its invention. It was also used

for pendulum rods in master clocks and similar alloys are now employed for

such diverse applications as the lining of tanks in vessels carrying 'liquid

natural gas' and in the many types of thermostat in modern heating

equipment.

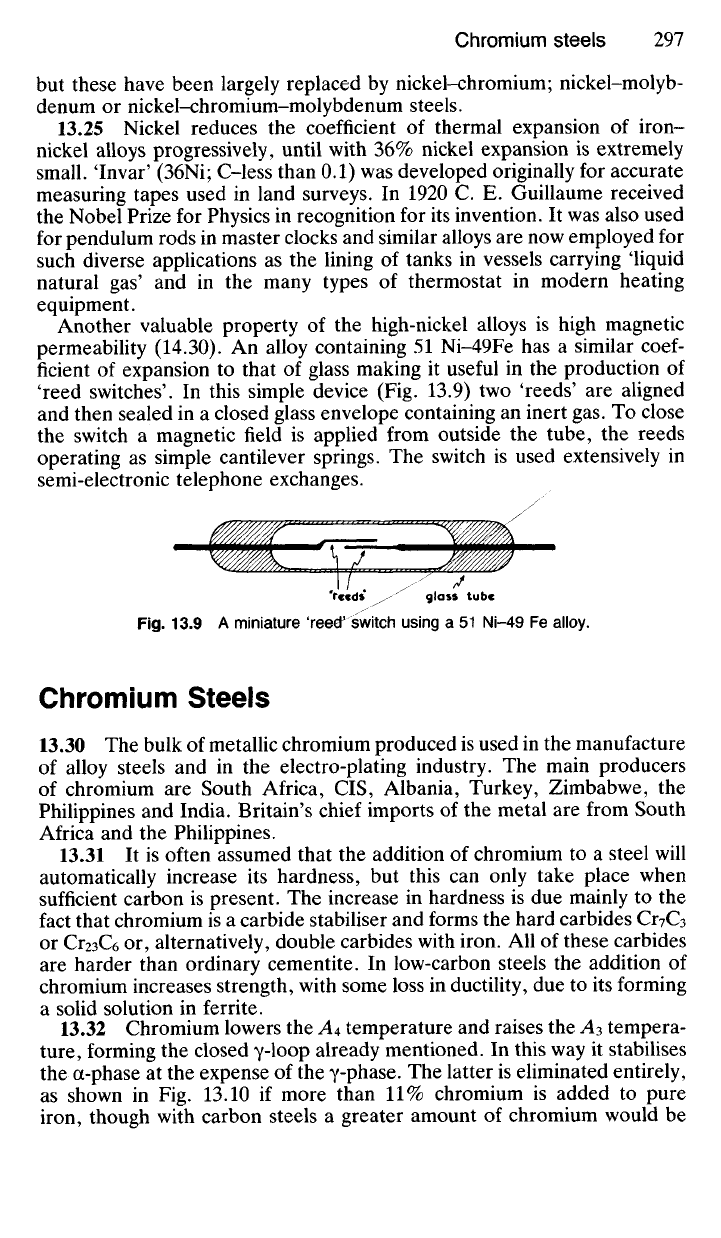

Another valuable property of the high-nickel alloys is high magnetic

permeability (14.30). An alloy containing 51 Ni-49Fe has a similar

coef-

ficient of expansion to that of glass making it useful in the production of

'reed switches'. In this simple device (Fig. 13.9) two 'reeds' are aligned

and then sealed in a closed glass envelope containing an inert gas. To close

the switch a magnetic field is applied from outside the tube, the reeds

operating as simple cantilever springs. The switch is used extensively in

semi-electronic telephone exchanges.

Fig.

13.9 A miniature 'reeef switch using a 51 Ni-49 Fe alloy.

Chromium Steels

13.30 The bulk of metallic chromium produced is used in the manufacture

of alloy steels and in the electro-plating industry. The main producers

of chromium are South Africa, CIS, Albania, Turkey, Zimbabwe, the

Philippines and India. Britain's chief imports of the metal are from South

Africa and the Philippines.

13.31 It is often assumed that the addition of chromium to a steel will

automatically increase its hardness, but this can only take place when

sufficient carbon is present. The increase in hardness is due mainly to the

fact that chromium is a carbide stabiliser and forms the hard carbides Cr

7

C

3

or O23C6 or, alternatively, double carbides with iron. All of these carbides

are harder than ordinary cementite. In low-carbon steels the addition of

chromium increases strength, with some loss in ductility, due to its forming

a solid solution in ferrite.

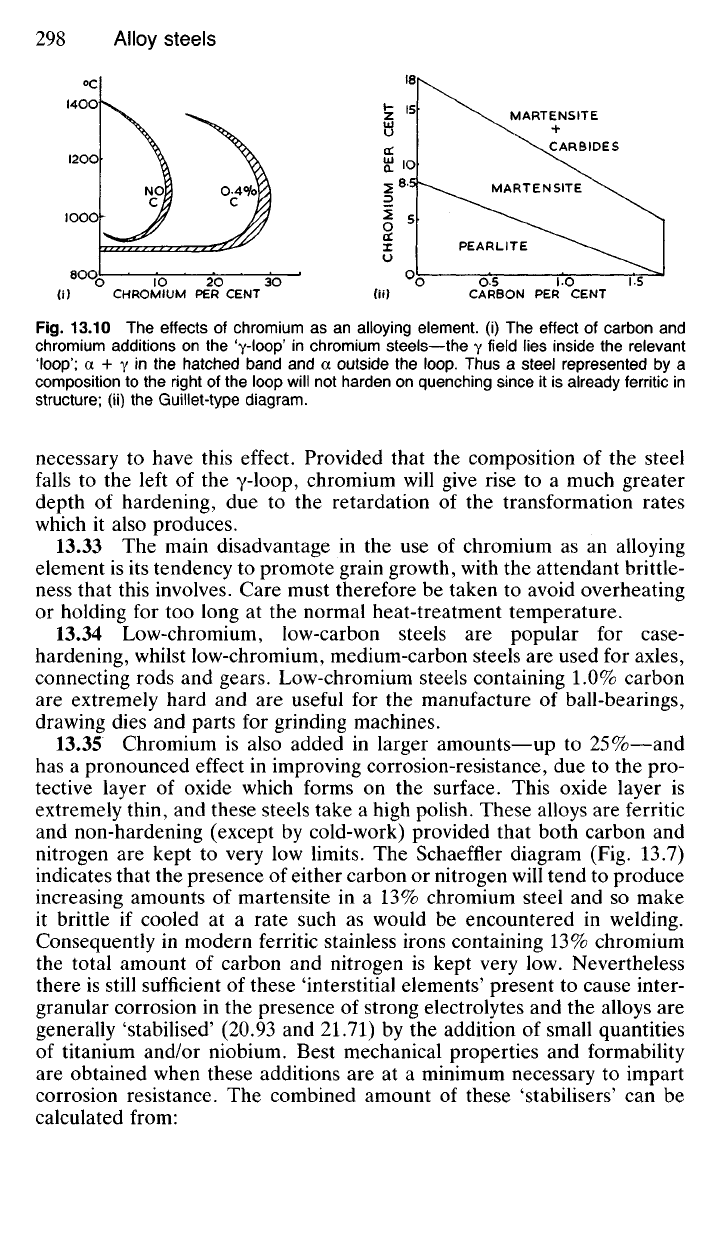

13.32 Chromium lowers the

AA

temperature and raises the A3 tempera-

ture,

forming the closed y-loop already mentioned. In this way it stabilises

the a-phase at the expense of the y-phase. The latter is eliminated entirely,

as shown in Fig. 13.10 if more than 11% chromium is added to pure

iron, though with carbon steels a greater amount of chromium would be

'reeds

glass tube

Fig.

13.10 The effects of chromium as an alloying element, (i) The effect of carbon and

chromium additions on the yioop' j

n

chromium steels—the y field lies inside the relevant

'loop';

a + Y in the hatched band and a outside the loop. Thus a steel represented by a

composition to the right of the loop will not harden on quenching since it is already ferritic in

structure; (ii) the Guillet-type diagram.

necessary to have this effect. Provided that the composition of the steel

falls to the left of the y-loop, chromium will give rise to a much greater

depth of hardening, due to the retardation of the transformation rates

which it also produces.

13.33 The main disadvantage in the use of chromium as an alloying

element is its tendency to promote grain growth, with the attendant brittle-

ness that this involves. Care must therefore be taken to avoid overheating

or holding for too long at the normal heat-treatment temperature.

13.34 Low-chromium, low-carbon steels are popular for case-

hardening, whilst low-chromium, medium-carbon steels are used for axles,

connecting rods and gears. Low-chromium steels containing 1.0% carbon

are extremely hard and are useful for the manufacture of ball-bearings,

drawing dies and parts for grinding machines.

13.35 Chromium is also added in larger amounts—up to 25%—and

has a pronounced effect in improving corrosion-resistance, due to the pro-

tective layer of oxide which forms on the surface. This oxide layer is

extremely thin, and these steels take a high polish. These alloys are ferritic

and non-hardening (except by cold-work) provided that both carbon and

nitrogen are kept to very low limits. The Schaeffler diagram (Fig. 13.7)

indicates that the presence of either carbon or nitrogen will tend to produce

increasing amounts of martensite in a 13% chromium steel and so make

it brittle if cooled at a rate such as would be encountered in welding.

Consequently in modern ferritic stainless irons containing 13% chromium

the total amount of carbon and nitrogen is kept very low. Nevertheless

there is still sufficient of these 'interstitial elements' present to cause inter-

granular corrosion in the presence of strong electrolytes and the alloys are

generally 'stabilised' (20.93 and 21.71) by the addition of small quantities

of titanium and/or niobium. Best mechanical properties and formability

are obtained when these additions are at a minimum necessary to impart

corrosion resistance. The combined amount of these 'stabilisers' can be

calculated from:

CHROMIUM PER

CENT

CHROMIUM PER CENT

oc

MARTENSITE

CARBIDES

MARTENSITE

PEARLITE

CARBON PER CENT

When carefully refined stainless irons contain no more than 0.01% each

of carbon and nitrogen the above formula indicates a total requirement of

titanium and niobium of no more than 0.28%.

As the Schaeffler diagram indicates, it is far easier to stabilise a ferritic

structure in those stainless irons containing 17-26% chromium and less

than 0.1% carbon.

Ferritic stainless irons are used widely in the chemical engineering indus-

tries.

Lower-grade alloys are used for domestic purposes such as stainless-

steel sinks; and in food containers, refrigerator parts, beer barrels, cutlery

and table-ware. The best-known alloy in this group is 'stainless iron', con-

taining 13% chromium and usually less than 0.05% carbon. Recently

British Steel have developed a similar alloy ('Hyform 409') for the manu-

facture of corrosion-resistant motor-car exhaust systems. This contains

12%

chromium which gives optimum formability whilst still retaining

adequate corrosion resistance. Nitrogen and carbon are kept to a minimum

and titanium is added as a stabiliser. Such an exhaust system would outlast

many made in the usual mild steel. It will be up to 'consumer pressure' to

back British Steel in this venture—otherwise we will continue to get the

rotten cars we deserve.

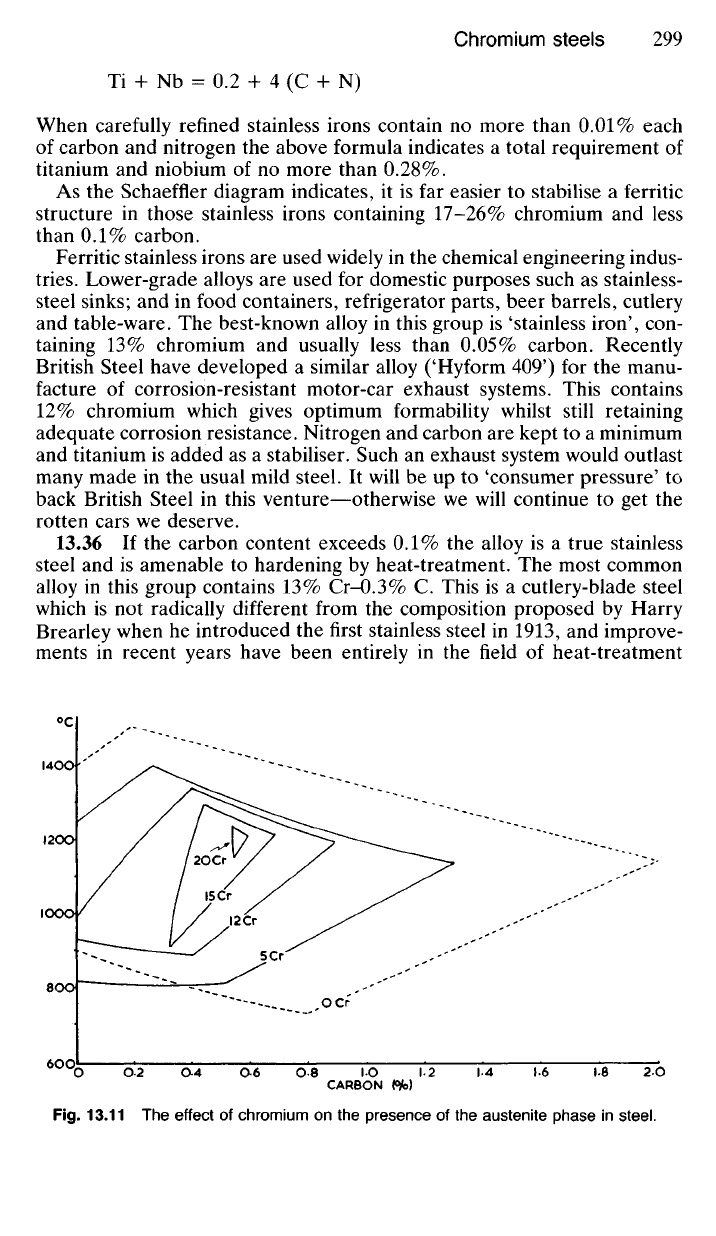

13.36 If the carbon content exceeds 0.1% the alloy is a true stainless

steel and is amenable to hardening by heat-treatment. The most common

alloy in this group contains 13%

Cr-0.3%

C. This is a cutlery-blade steel

which is not radically different from the composition proposed by Harry

Brearley when he introduced the first stainless steel in 1913, and improve-

ments in recent years have been entirely in the field of heat-treatment

0

C

CARBON (Ph)

Fig.

13.11 The effect of chromium on the presence of the austenite phase in steel.

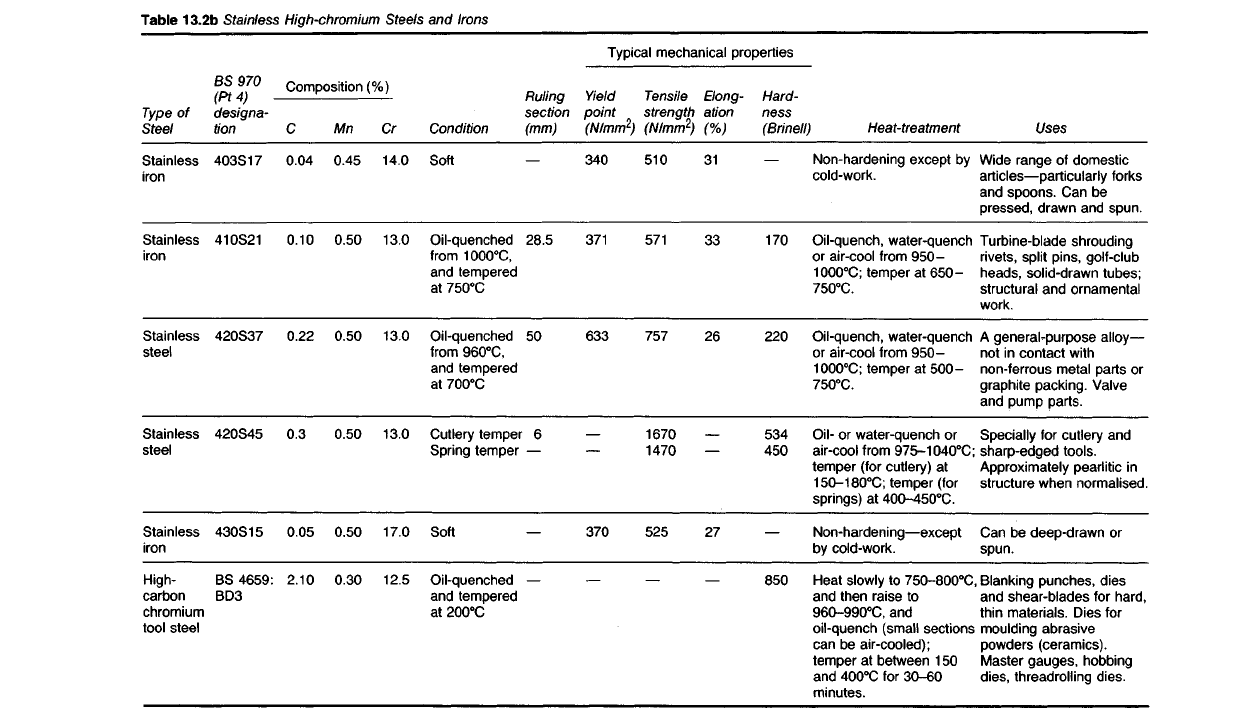

Table

13.2a

Low-chromium Steels

Uses

General blacksmith's

and boilermaker's

tools

and

chisels.

Hot

and cold sates.

Swages. Hot-stamping

and forging dies.

Builder's, mason's

and

miner's tools. Spring

collets,

chuck

and

vice

jaws.

Turning

mandrels

and

lathe

centres.

Agricultural

machine

parts,

machine-tool

components. Lining

plates, paddles

and

drums for concrete

and

tar

mixers. Excavator

cutting blades

and

teeth. Automobile

axles, connecting-rods

and steering arms.

Spanners

and

small

tools.

Side-wear situations

(tightly-curved railway

track).

Ball-

and

roller-bearings. Roller-

and ball-races.

Instrument pivots

and

spindles. Cams. Small

rolls.

Heat-treatment

Oil-quench

from

800-850

0

C.

Temper:

(1)

for cold-working

tools

at 200-300

0

C;

(2) for hot-working

tools

at 400-600

0

C.

Oil-quench

from

860

0

C;

temper from

550-700

0

C.

Oil-quench

from

810

0

C;

temper

at

150

0

C

Typical mechanical properties

Hard-

ness

(Brinell)

700

250

250

~200

340

850

Reduction

area Izod

(%)

(J)

34

54

95

61

122

Elong-

ation

15

18

22

8

Tensile

strength

850

850

700

1140

Yield

point

(N/mm

2

)

620

680

500

Ruling

section

(mm)

63.5

28.5

100

28.5

Condition

Oil-quenched

and tempered

at

200

0

C.

Oil-quenched

and tempered

at

400

0

C.

Oil-quenched

and tempered

at

650

0

C.

Hardened

Composition

(%)

C

Mn Cr

0.60

0.65 0.65

0.45

0.90 1.00

0.75

1.0 1.1

1.00

0.45 1.40

BS

970

desig-

nation

526M60

530M40

534A99

Type

of

Steel

'60'

C-Cr

steel

1%Cr

steel

1%

Cr

rail

steel

1%C-Cr

steel

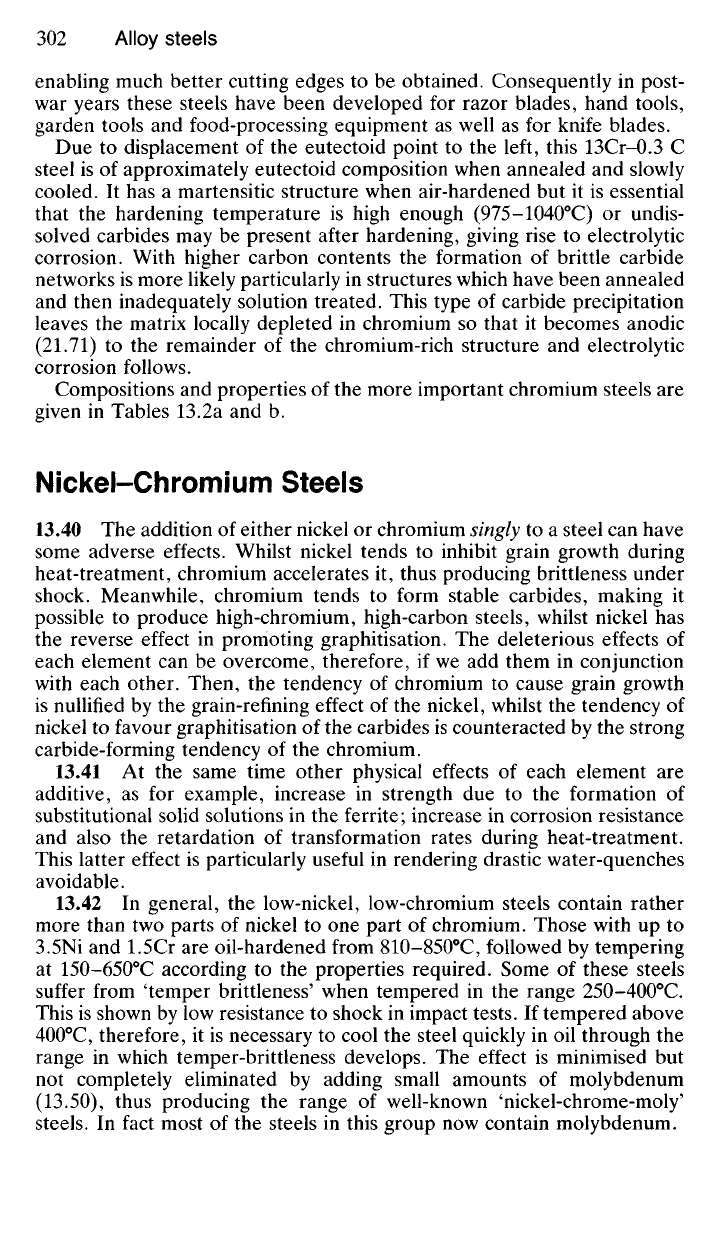

Table

13.2b Stainless

High-chromium

Steels and Irons

Uses

Wide range of domestic

articles—particularly

forks

and spoons. Can be

pressed,

drawn and spun.

Turbine-blade shrouding

rivets,

split

pins, golf-club

heads, solid-drawn tubes;

structural

and ornamental

work.

A

general-purpose alloy—

not

in contact with

non-ferrous

metal parts or

graphite packing. Valve

and pump parts.

Specially for cutlery and

sharp-edged tools.

Approximately

pearlitic in

structure

when normalised.

Can be deep-drawn or

spun.

Blanking punches, dies

and shear-blades for hard,

thin

materials. Dies for

moulding abrasive

powders

(ceramics).

Master

gauges,

hobbing

dies, threadrolling dies.

Heat-treatment

Non-hardening except by

cold-work.

Oil-quench, water-quench

or

air-cool

from

950-

1000

0

C;

temper at 650-

75O

0

C.

Oil-quench, water-quench

or

air-cool

from

950-

1000

0

C;

temper at 500-

750

0

C.

Oil- or water-quench or

air-cool

from

975-1040

0

C;

temper

(for cutlery) at

150-180

0

C;

temper (for

springs)

at

400-450

0

C.

Non-hardening—except

by

cold-work.

Heat slowly to

750-800

0

C

1

and then raise to

960-990

0

C,

and

oil-quench (small sections

can be air-cooled);

temper

at

between

150

and

400

0

C

for

30-60

minutes.

Typical mechanical properties

Hard-

ness

(Brinell)

170

220

534

450

850

Elong-

ation

(%)

31

33

26

27

Tensile

strength

(N/mm

2

)

510

571

757

1670

1470

525

Yield

point

(N/mm

2

)

340

371

633

370

Ruling

section

(mm)

28.5

50

6

Condition

Soft

Oil-quenched

from

1000

0

C,

and tempered

at

750

0

C

Oil-quenched

from

960

0

C,

and tempered

at

700

0

C

Cutlery

temper

Spring

temper

Soft

Oil-quenched

and tempered

at

200

0

C

Composition (%)

Cr

14.0

13.0

13.0

13.0

17.0

12.5

Mn

0.45

0.50

0.50

0.50

0.50

0.30

C

0.04

0.10

0.22

0.3

0.05

2.10

BS 970

(Pt

4)

designa-

tion

403S17

410S21

420S37

420S45

430S15

BS

4659:

BD3

Type

of

Steel

Stainless

iron

Stainless

iron

Stainless

steel

Stainless

steel

Stainless

iron

High-

carbon

chromium

tool steel

enabling much better cutting edges to be obtained. Consequently in post-

war years these steels have been developed for razor blades, hand tools,

garden tools and food-processing equipment as well as for knife blades.

Due to displacement of the eutectoid point to the left, this 13Cr-0.3 C

steel is of approximately eutectoid composition when annealed and slowly

cooled. It has a martensitic structure when air-hardened but it is essential

that the hardening temperature is high enough (975-1040

0

C) or undis-

solved carbides may be present after hardening, giving rise to electrolytic

corrosion. With higher carbon contents the formation of brittle carbide

networks is more likely particularly in structures which have been annealed

and then inadequately solution treated. This type of carbide precipitation

leaves the matrix locally depleted in chromium so that it becomes anodic

(21.71) to the remainder of the chromium-rich structure and electrolytic

corrosion follows.

Compositions and properties of the more important chromium steels are

given in Tables 13.2a and b.

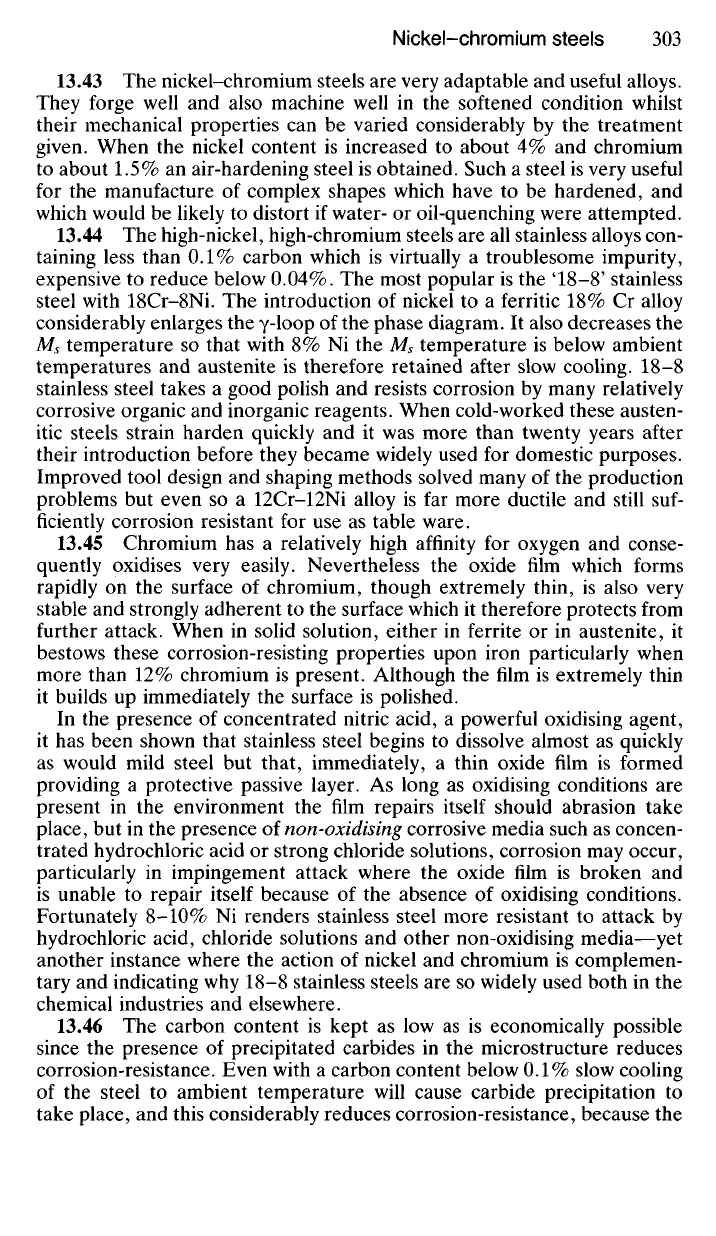

Nickel-Chromium Steels

13.40 The addition of either nickel or chromium singly to a steel can have

some adverse effects. Whilst nickel tends to inhibit grain growth during

heat-treatment, chromium accelerates it, thus producing brittleness under

shock. Meanwhile, chromium tends to form stable carbides, making it

possible to produce high-chromium, high-carbon steels, whilst nickel has

the reverse effect in promoting graphitisation. The deleterious effects of

each element can be overcome, therefore, if we add them in conjunction

with each other. Then, the tendency of chromium to cause grain growth

is nullified by the grain-refining effect of the nickel, whilst the tendency of

nickel to favour graphitisation of the carbides is counteracted by the strong

carbide-forming tendency of the chromium.

13.41 At the same time other physical effects of each element are

additive, as for example, increase in strength due to the formation of

substitutional solid solutions in the ferrite; increase in corrosion resistance

and also the retardation of transformation rates during heat-treatment.

This latter effect is particularly useful in rendering drastic water-quenches

avoidable.

13.42 In general, the low-nickel, low-chromium steels contain rather

more than two parts of nickel to one part of chromium. Those with up to

3.5Ni and 1.5Cr are oil-hardened from 810-850

0

C, followed by tempering

at 150-650

0

C according to the properties required. Some of these steels

suffer from 'temper brittleness' when tempered in the range 250-400

0

C.

This is shown by low resistance to shock in impact tests. If tempered above

400

0

C,

therefore, it is necessary to cool the steel quickly in oil through the

range in which temper-brittleness develops. The effect is minimised but

not completely eliminated by adding small amounts of molybdenum

(13.50),

thus producing the range of well-known 'nickel-chrome-moly'

steels.

In fact most of the steels in this group now contain molybdenum.

13.43 The nickel-chromium steels are very adaptable and useful alloys.

They forge well and also machine well in the softened condition whilst

their mechanical properties can be varied considerably by the treatment

given. When the nickel content is increased to about 4% and chromium

to about 1.5% an air-hardening steel is obtained. Such a steel is very useful

for the manufacture of complex shapes which have to be hardened, and

which would be likely to distort if water- or oil-quenching were attempted.

13.44 The high-nickel, high-chromium steels are all stainless alloys con-

taining less than 0.1% carbon which is virtually a troublesome impurity,

expensive to reduce below 0.04%. The most popular is the

'18-8'

stainless

steel with 18Cr-8Ni. The introduction of nickel to a ferritic 18% Cr alloy

considerably enlarges the y-loop of the phase diagram. It also decreases the

M

s

temperature so that with 8% Ni the M

s

temperature is below ambient

temperatures and austenite is therefore retained after slow cooling. 18-8

stainless steel takes a good polish and resists corrosion by many relatively

corrosive organic and inorganic reagents. When cold-worked these austen-

itic steels strain harden quickly and it was more than twenty years after

their introduction before they became widely used for domestic purposes.

Improved tool design and shaping methods solved many of the production

problems but even so a 12Cr-12Ni alloy is far more ductile and still suf-

ficiently corrosion resistant for use as table ware.

13.45 Chromium has a relatively high affinity for oxygen and conse-

quently oxidises very easily. Nevertheless the oxide film which forms

rapidly on the surface of chromium, though extremely thin, is also very

stable and strongly adherent to the surface which it therefore protects from

further attack. When in solid solution, either in ferrite or in austenite, it

bestows these corrosion-resisting properties upon iron particularly when

more than 12% chromium is present. Although the film is extremely thin

it builds up immediately the surface is polished.

In the presence of concentrated nitric acid, a powerful oxidising agent,

it has been shown that stainless steel begins to dissolve almost as quickly

as would mild steel but that, immediately, a thin oxide film is formed

providing a protective passive layer. As long as oxidising conditions are

present in the environment the film repairs itself should abrasion take

place, but in the presence of non-oxidising corrosive media such as concen-

trated hydrochloric acid or strong chloride solutions, corrosion may occur,

particularly in impingement attack where the oxide film is broken and

is unable to repair itself because of the absence of oxidising conditions.

Fortunately 8-10% Ni renders stainless steel more resistant to attack by

hydrochloric acid, chloride solutions and other non-oxidising media—yet

another instance where the action of nickel and chromium is complemen-

tary and indicating why 18-8 stainless steels are so widely used both in the

chemical industries and elsewhere.

13.46 The carbon content is kept as low as is economically possible

since the presence of precipitated carbides in the microstructure reduces

corrosion-resistance. Even with a carbon content below 0.1% slow cooling

of the steel to ambient temperature will cause carbide precipitation to

take place, and this considerably reduces corrosion-resistance, because the

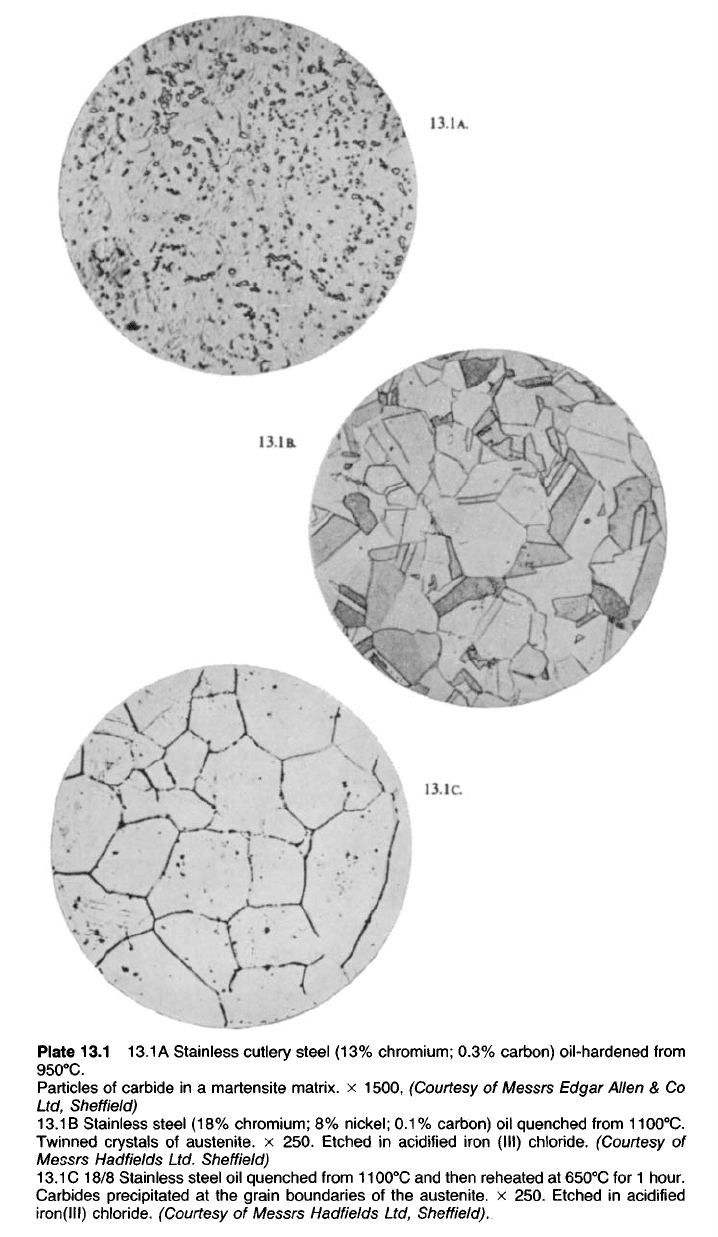

Plate 13.1

13.1

A Stainless cutlery steel (13% chromium; 0.3% carbon) oil-hardened from

950

0

C.

Particles of carbide in a martensite matrix, x 1500, (Courtesy of Messrs Edgar Allen & Co

Ltd, Sheffield)

13.1 B Stainless steel (18% chromium; 8% nickel; 0.1% carbon) oil quenched from 1100

0

C.

Twinned crystals of austenite. x 250. Etched in acidified iron (III) chloride. (Courtesy of

Messrs Hadfields Ltd. Sheffield)

13.1

C 18/8 Stainless steel oil quenched from 1100

0

C and then reheated at 650

0

C for 1 hour.

Carbides precipitated at the grain boundaries of the austenite. x 250. Etched in acidified

iron(lll) chloride. (Courtesy of Messrs Hadfields Ltd, Sheffield).

13.1c

13.1a

13.1A.

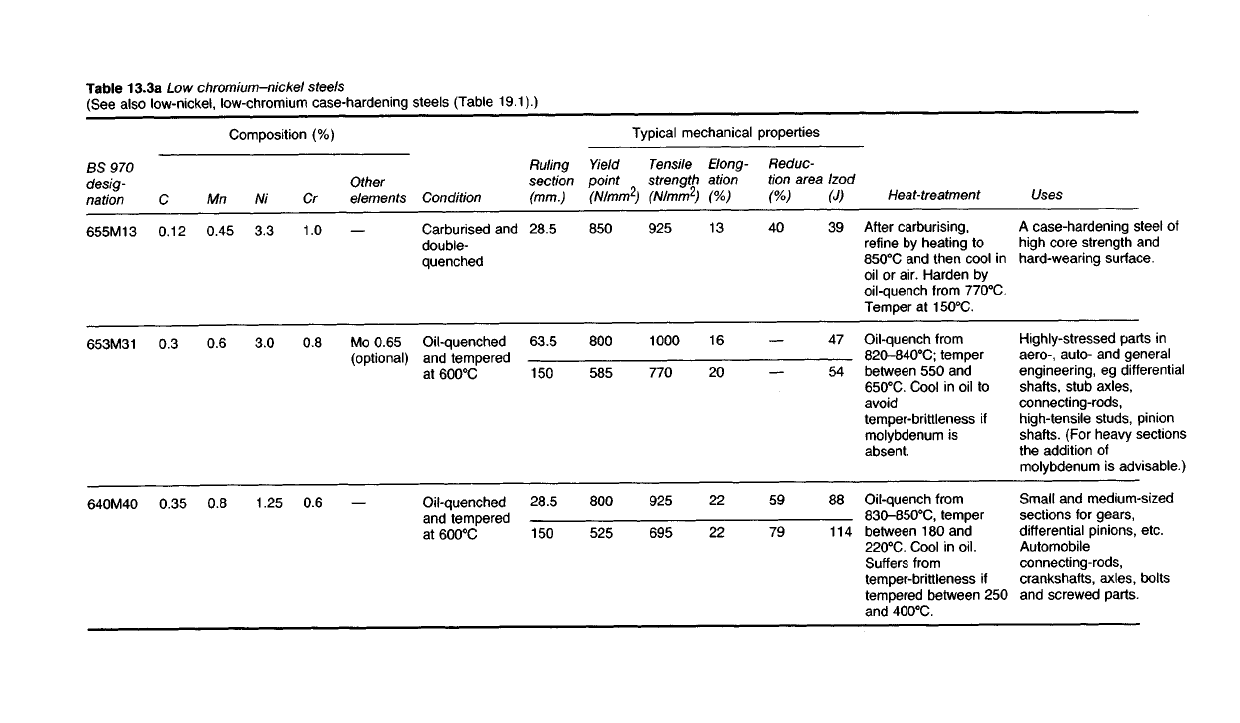

Table 13.3a Low chromium-nickel

steels

(See

also low-nickel, low-chromium case-hardening steels (Table 19.1).)

Uses

A

case-hardening steel of

high core strength and

hard-wearing surface.

Highly-stressed parts in

aero-, auto- and general

engineering, eg differential

shafts,

stub axles,

connecting-rods,

high-tensile

studs, pinion

shafts.

(For heavy sections

the addition of

molybdenum is advisable.)

Small

and medium-sized

sections for gears,

differential pinions, etc.

Automobile

connecting-rods,

crankshafts, axles, bolts

and screwed parts.

Heat-treatment

After

carburising,

refine

by heating to

850

0

C and then cool in

oil or air. Harden by

oil-quench

from

770

0

C.

Temper at 150

0

C.

Oil-quench from

820-840

0

C;

temper

between

550 and

650

0

C. Cool in oil to

avoid

temper-brittleness if

molybdenum is

absent.

Oil-quench

from

830-850

0

C,

temper

between

180 and

220

0

C. Cool in oil.

Suffers

from

temper-brittleness if

tempered between 250

and 400

0

C.

Typical

mechanical properties

Izod

(J)

39

47

88

114

Reduc-

tion

area

(%)

40

59

79

Elong-

ation

13

16

20

22

22

Tensile

strength

(N/mm

2

)

925

1000

770

925

695

Yield

point

(N/mm

2

)

850

800

585

800

525

Ruling

section

(mm.)

28.5

63.5

150

28.5

150

Condition

Carburised and

double-

quenched

Oil-quenched

and tempered

at

600

0

C

Oil-quenched

and tempered

at

600

0

C

Composition (%)

Other

elements

Mo

0.65

(optional)

Cr

1.0

0.8

0.6

Ni

3.3

3.0

1.25

Mn

0.45

0.6

0.8

C

0.12

0.3

0.35

BS

970

desig-

nation

655M13

653M31

640M40