Heiman G. Basic Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

28 CHAPTER 2 / Statistics and the Research Process

In our studying example, we’d have an ordinal scale if we assigned a 1 to students who

scored best on the test, a 2 to those in second place, and so on. Then we’d ask, “As

study times change, do students’ ranks also tend to change?” Or, if an experiment com-

pares the conditions of first graders to second graders, then this independent variable

involves an ordinal scale. The key here is that ordinal scores indicate only a relative

amount—identifying who scored relatively high or low. Also, there is no zero in ranks,

and the same amount does not separate every pair of adjacent scores: 1st may be only

slightly ahead of 2nd, but 2nd may be miles ahead of 3rd.

A third approach is to use an interval scale. Here each score indicates an actual

quantity, and an equal amount separates any adjacent scores. (For interval scores, re-

member equal intervals between them.) However, although interval scales do include

the number 0, it is not a true zero—it does not mean none of the variable is present.

Therefore, the key here is that you can have less than zero, so an interval scale allows

negative numbers. For example, temperature (in Celsius or Fahrenheit) involves an in-

terval scale: Because 0° does not mean that zero heat is present, you can have even less

heat at 1°. In research, interval scales are common with intelligence or personality

tests: A score of zero does not mean zero intelligence or zero personality. Or, in our

studying research we might determine the average test score and then assign students a

zero if they are average, a ⫹1, ⫹2, and so on, for the amount they are above average,

and a ⫺1, ⫺2, and so on, for the amount they are below average. Then we’d see if more

positive scores tend to occur with higher study times. Or, if we create conditions based

on whether participants are in a positive, negative, or neutral mood, then this indepen-

dent variable reflects an interval scale.

Notice that with an interval scale, it is incorrect to make “ratio” statements that com-

pare one score to another score. For example, at first glance it seems that 4°C is twice as

warm as 2°C. However, if we measure the same physical temperatures using the Fahren-

heit scale, we would have about 35° and 39°, respectively. Now one temperature is not

twice that of the other. Essentially, if we don’t know the true amount of a variable that is

present at 0, then we don’t know the true amount that is present at any other score.

Only with our final scale of measurement, a ratio scale, do the scores reflect the true

amount of the variable that is present. Here the scores measure an actual amount, there

is an equal unit of measurement, and 0 truly means that none of the variable is present.

The key here is that you cannot have negative numbers because you cannot have less

than nothing. Also, only with ratio scores can we make “ratio” statements, such as “4 is

twice as much as 2.” (So for ratio, think ratio!) We used ratio scales in our previous

examples when measuring the number of errors and the number of hours studied. Like-

wise, in an experiment, if we compare the conditions of having people on diets consist-

ing of either 1000, 1500, or 2000 calories a day, then this independent variable involves

a ratio scale.

We can study relationships that involve any combination of the above scales.

REMEMBER The scale of measurement reflected by scores may be nominal,

ordinal, interval, or ratio.

Continuous versus Discrete Scales

A measurement scale may be either continuous or discrete. A continuous scale allows

for fractional amounts; it “continues” between the whole-number amounts, so decimals

make sense. The variable of age is continuous because someone can be 19.6879 years

old. On the other hand, some variables involve a discrete scale, which are measured

only in whole amounts. Here, decimals do not make sense. For example, whether you

2

The Characteristics of Scores 29

are male or female or in first or second grade are discrete variables because you can be

in one group or the other, but not in-between. (Some variables may seem to involve

fractions—such as shoe size—but they are still discrete variables, because smaller divi-

sions are not possible and, again, there is no in between.)

Note: when a discrete variable has only two possible categories or scores, it is called

a dichotomous variable. Male/female or living/dead are dichotomous variables.

Usually researchers assume that nominal or ordinal variables are discrete and that

interval or ratio variables are at least theoretically continuous. For example, in-

telligence tests are designed to produce whole-number scores. But, theoretically, an

IQ of 95.6 makes sense, so intelligence is a theoretically continuous (interval) vari-

able. Likewise, it sounds strange if the government reports that the average family

has 2.4 children because no one has .4 of a child. However, it makes sense to treat

this ratio variable as if it is continuous, because we can interpret what it means if

this year the average is 2.4 children, but last year the average was 2.8. (I’ve heard that

a recent survey showed the average American home contains 2.5 people and 2.7

televisions!)

REMEMBER Whether a variable is continuous or discrete and whether it is

measured using a nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio scale are factors that de-

termine which statistical procedure to apply.

To help you remember the four scales of measurement, Table 2.6 summarizes their

characteristics.

Type of Measurement Scale

Nominal Ordinal Interval Ratio

Quality Relative Quantity Quantity

quantity

No No Yes Yes

No No No Yes

To identify To judge who is To convey the To count the

males and 1st, 2nd, etc., in results of number of

females as 1 aggressiveness intelligence and correct answers

and 2 personality tests on a test

Telephone Letter grades Checkbook balance Weight

numbers

Elementary Individual’s Distance

Social Security school grade standing relative traveled

numbers to class average

TABLE 2.6

Summary of Types of

Measurement Scales

Each column describes the

characteristics of the scale.

What Does the

Scale Indicate?

Is There an

Equal Unit of

Measurement?

Is There a True

Zero?

How Might the

Scale be Used

in Reasearch?

Additional

Examples

■

Nominal scales identify categories and ordinal

scales reflect rank order. Both interval and ratio

scales measure actual quantities, but negative

numbers can occur with interval scales and not

with ratio scales.

■

Interval and ratio scales are assumed to be continu-

ous scales, which allow fractional amounts; nominal

and ordinal scales are assumed to be discrete scales,

which do not allow fractional amounts.

continued

A QUICK REVIEW

30 CHAPTER 2 / Statistics and the Research Process

STATISTICS IN PUBLISHED RESEARCH: USING STATISTICAL TERMS

You have already begun to learn the secret language found in published research.

You’ll frequently encounter such terms as relationship, independent and dependent

variable, condition, or statistic. Also, that phrase “as a function of” is common. Often

it is in the title of a graph, so seeing “Agility as a Function of Age” indicates that the

graph shows the relationship between scores that measure participants’ ages and

Y scores that measure agility. The phrase is also used in the title of reports. For exam-

ple, “Anxiety When Dating as a Function of Introversion Level” indicates that the

researcher wondered if people are more or less anxious about going on a date, depend-

ing on the particular (given) amount of introversion that they exhibit.

The reason that published research seems to involve a secret language is because many

details are left out. Implicitly it is assumed that the reader of a report (you) has taken a

statistics course and so understands the terminology of statistics and research. This means

that most of the terms that we’ll discuss are seldom defined in published reports. There-

fore, for you to understand research and apply statistical procedures (let alone understand

this book), these terms need to become part of your everyday vocabulary.

X

As you proceed through this course, however, don’t let the terminology and details ob-

scure your ultimate purpose. Keep things in perspective by remembering the overall

logic of research, which can be summarized by the following five steps:

1. Based on a hypothesized law of nature, we design either an experiment or a corre-

lational study to measure variables and to observe the predicted relationship in the

sample.

2. We use descriptive statistics to understand the scores and the relationship in the

sample.

3. We use inferential procedures to decide whether the sample accurately represents

the scores and relationship that we would find if we could study everyone in the

population.

PUTTING IT

ALL TOGETHER

MORE EXAMPLES

If your grade on an essay exam is based on the num-

ber of correct statements you include, then a ratio

scale is involved; if it is based on how much your

essay is better or worse than what the professor

expected, an interval scale is involved; if it indicates

that yours was relatively one of the best or worst

essays in the class, this is an ordinal scale (as is

pass/fail, which is dichotomous); if it is based on the

last digit of your ID number, then a nominal scale is

involved. If you can receive one grade or another, but

nothing in between, it involves a discrete scale; if frac-

tions are possible, it involves a continuous scale.

For Practice

1. Whether you are ahead or behind when gambling

involves a _____ scale.

2. The number of hours you slept last night involves

a _____ scale.

3. Your blood type involves a _____ scale.

4. Whether you are a lieutenant or major in the army

involves a _____ scale.

5. A _____ scale allows fractions; a _____ scale

allows only whole amounts.

Answers

1. interval 4. ordinal

2. ratio 5. continuous; discrete

3. nominal

Chapter Summary 31

4. By describing the scores and relationship that would be found in the population,

we are actually describing the behavior of everyone in a particular group in a par-

ticular situation.

5. By describing the behavior of everyone in a particular situation, we are describing

how a law of nature operates.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

1. The group of all individuals to which research applies is the population. The

subset of the population that is actually measured is the sample.

2. Usually, participants are selected using random sampling so that all scores in the

population have the same chance of being selected. The sample should be

representative. By chance, however, a sample may be unrepresentative.

3. A variable is anything that, when measured, can produce two or more different

scores. Variables may be quantitative, measuring a quantity or amount, or

qualitative, measuring a quality or category.

4. A relationship occurs when a change in scores on one variable is associated with a

consistent change in scores on another variable.

5. The term individual differences refers to the fact that no two individuals are identical.

6. Because of individual differences and external influences, relationships can have

varying strengths.

7. The “given” variable in any relationship is designated the variable, and we describe

a relationship using the format “changes in as a function of changes in .”

8. Descriptive statistics are used to organize, summarize, and describe sample data,

and to predict an individual’s score using the relationship with . Inferential

statistics are for deciding whether the sample data actually represent the relation-

ship that occurs in the population.

9. A statistic is a number that describes a characteristic of a sample of scores, sym-

bolized using a letter from the English alphabet. A statistic is used to infer or

estimate the corresponding parameter. A parameter is a number that describes a

characteristic of a population of scores, symbolized using a letter from the

Greek alphabet.

10. A study’s design is the particular way in which the study is laid out.

11. In an experiment, we manipulate the independent variable and then measure

participants’ scores on the dependent variable. A specific amount or category of

the independent variable is called a condition, treatment, or level.

12. In a correlational study, neither variable is actively manipulated. Scores on both

variables are simply measured and then the relationship is described.

13. In any type of research, if a relationship is observed, it may or may not mean that

changes in one variable cause the other variable to change.

XY

XY

X

32 CHAPTER 2 / Statistics and the Research Process

14. The four scales of measurement are (a) a nominal scale, in which numbers name

or identify a quality or characteristic; (b) an ordinal scale, in which numbers

indicate rank order; (c) an interval scale, in which numbers measure a specific

amount, but with no true zero; or (d) a ratio scale, in which numbers measure

a specific amount and 0 indicates truly zero amount.

15. A continuous variable can be measured in fractional amounts. A discrete variable

is measured only in whole amounts. A dichotomous variable is a discrete variable

that has only two amounts or categories.

KEY TERMS

as a function of 19

condition 23

continuous scale 28

correlational study 25

dependent variable 23

descriptive statistics 20

design 22

dichotomous variable 29

discrete scale 29

experiment 22

independent variable 22

individual differences 17

inferential statistics 21

interval scale 28

level 23

nominal scale 27

ordinal scale 27

parameter 22

participant 14

population 13

ratio scale 28

relationship 15

sample 13

statistic 21

strength of a relationship 17

treatment 23

variable 14

REVIEW QUESTIONS

(Answers for odd-numbered problems are in Appendix D.)

1. (a) What is a population? (b) What is a sample? (c) How are samples used to

make conclusions about populations? (d) What are researchers really referring to

when they talk about the population?

2. What do you see when (a) a relationship exists between two variables? (b) No

relationship is present?

3. What does the strength of a relationship refer to?

4. What pattern in the Y scores will produce a weaker relationship?

5. What are the two aspects of a study to consider when deciding on the particular

descriptive or inferential statistics that you should employ?

6. What is the difference between an experiment and a correlational study?

7. What is the difference between the independent variable and the conditions of the

independent variable?

8. In an experiment, what is the dependent variable?

9. What is the general purpose of all research, whether experiments or correlational

studies?

10. (a) What are descriptive statistics used for? (b) What are inferential statistics used

for?

11. (a) What is the difference between a statistic and a parameter? (b) What types of

symbols are used for statistics and parameters?

Application Questions 33

12. (a) Define the four scales of measurement. (b) What are continuous and discrete

variables? (c) Which scales of measurement are usually assumed to be discrete

and which are assumed to be continuous?

APPLICATION QUESTIONS

13. A student named Foofy (who you’ll be taking statistics with) conducted a survey.

In her sample, 83% of mothers employed outside the home would rather be home

raising children. She concluded that “the statistical analyses prove that most

working women would rather be at home.” What is the problem with this conclu-

sion?

14. In study A, a researcher gives participants various amounts of alcohol and then

observes any decrease in their ability to walk. In study B, a researcher notes the

various amounts of alcohol that participants drink at a party and then observes any

decrease in their ability to walk. (a) Which study is an experiment, and which is a

correlational study? Why? (b) Which study will be best for showing that drinking

alcohol causes an impairment in walking? Why?

15. Another student in your class, Poindexter, conducted a survey of college students

about their favorite beverage. Based on what the sample said, he concluded that

most college students prefer carrot juice to other beverages! What statistical argu-

ment can you give for not accepting this conclusion?

16. In each of the following experiments, identify the independent variable, the condi-

tions of the independent variable, and the dependent variable: (a) Studying

whether scores on a final exam are influenced by background music that is soft,

loud, or absent. (b) Comparing freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors with

respect to how much fun they have while attending college. (c) Studying whether

being first born, second born, or third born is related to intelligence. (d)

Examining whether length of daily exposure to a sun lamp (15 minutes versus

60 minutes) alters self-reported depression. (e) Studying whether being in a room

with blue walls, green walls, red walls, or beige walls influences the number of

aggressive acts produced by adolescents.

17. List the scales of measurement, starting with the scale that provides the most pre-

cise information about the amount of a variable present and ending with the scale

that provides the least precise information.

18. Using the terms sample, population, variable, statistics, and parameter,

summarize the steps a researcher follows, starting with a hypothesis and

ending with a conclusion about a nature.

19. For the following data sets, which show a relationship?

Sample A Sample B Sample C Sample D

XY XY XY XY

110 2040 1320 9271

110 2042 1319 9377

110 2240 1318 9377

220 2241 1317 9575

220 2340 1315 9674

330 2440 1314 9773

330 2442 1313 9871

34 CHAPTER 2 / Statistics and the Research Process

20. Which sample in question 19 shows the strongest relationship? How do you

know?

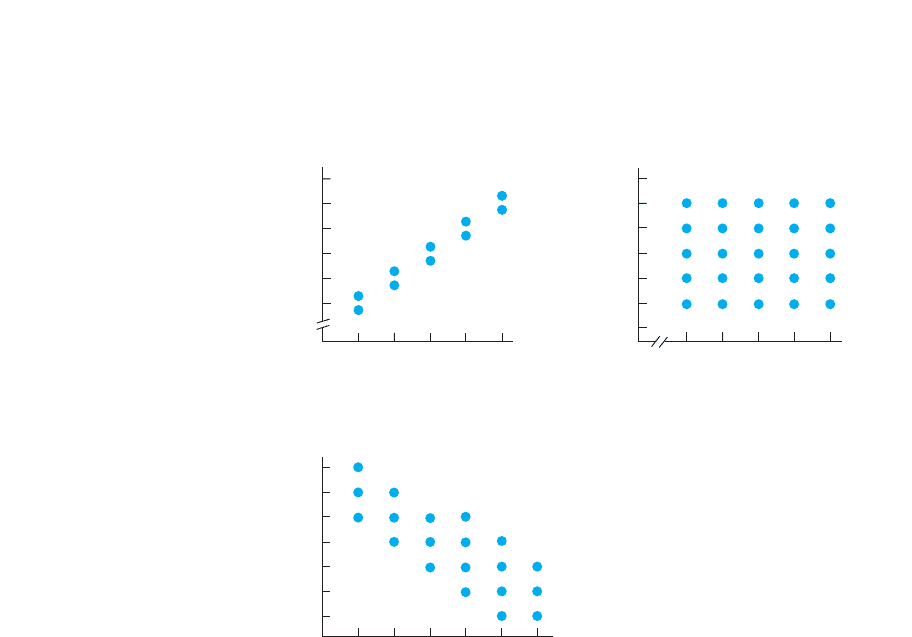

21. Which of the graphs below depict a relationship? How do you know?

15 20

Age scores

Weight scores

150

140

130

120

10

160

170

25

80 100 110

IQ scores

Age scores

40

30

20

10

90

50

60

120

70

7

Shoe size

Speed scores

20

15

10

8

25

30

35

Study A

Study B

Study C

5

5

0

9

0

0

10 11 12

22. Which study in question 21 demonstrates the strongest relationship? How do you

know?

23. In question 21, why is each relationship a telltale sign that a law of nature is at

work?

24. (a) Poindexter says that Study A in problem 21 examines age scores as a function

of weight scores. Is he correct? (b) He also claims that in Study C the researcher

is asking, “For a given shoe size, what speed scores occur?” Is he correct?

(c) If the studies in question 21 were conducted as experiments, in each, which

variable is the independent variable and which is the dependent variable?

Application Questions 35

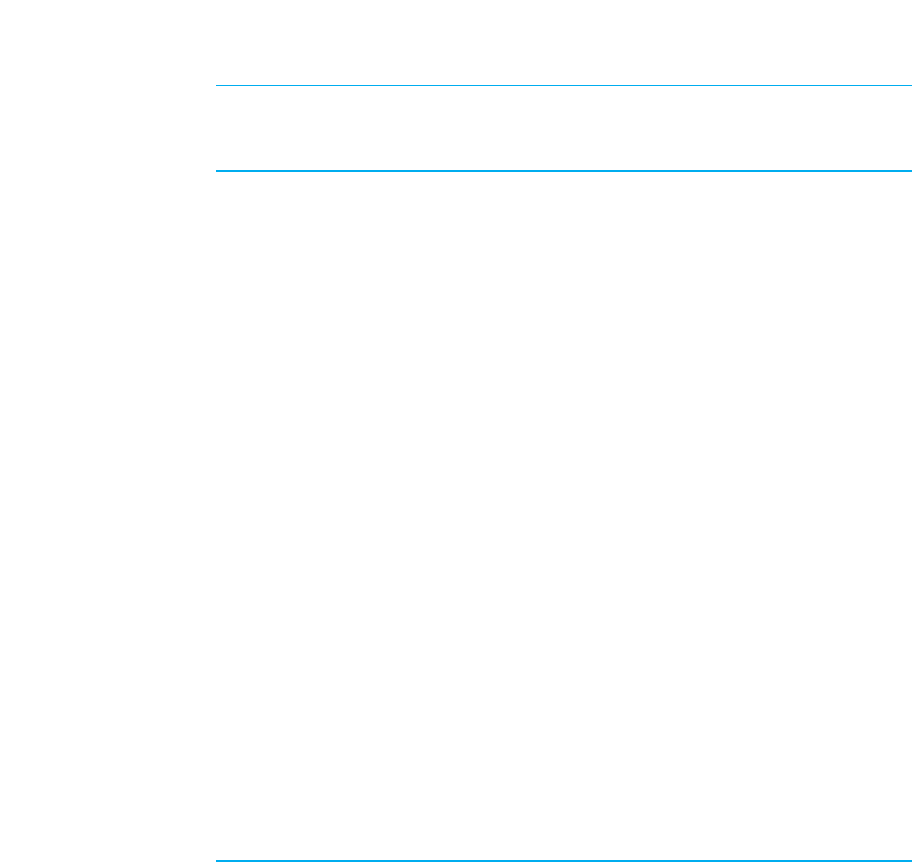

25. Complete the chart below to identify the characteristics of each variable.

Qualitative Continuous, Type of

or Discrete, or Measurement

Variable Quantitative Dichotomous Scale

Gender ________ ________ ________

Academic major ________ ________ ________

Number of minutes before ________ ________ ________

and after an event

Restaurant ratings ________ ________ ________

(best, next best, etc.)

Speed (miles per hr) ________ ________ ________

Dollars in your pocket ________ ________ ________

Change in weight (in lb) ________ ________ ________

Checking account balance ________ ________ ________

Reaction time ________ ________ ________

Letter grades ________ ________ ________

Clothing size ________ ________ ________

Registered voter ________ ________ ________

Therapeutic approach ________ ________ ________

Schizophrenia type ________ ________ ________

Work absences ________ ________ ________

Words recalled ________ ________ ________

36

So, we’re off into the wonderful world of descriptive statistics. Recall that descriptive

statistics tell us the obvious things we would ask about the relationship and scores in a

sample. Before we examine the relationship between two variables, however, we first

summarize the scores from each variable alone. Then, two important things that we

always wish to know are: Which scores occurred, and how often did each occur? The

way to answer this is to organize the scores into tables and graphs based on what are

called frequency distributions. In this chapter, you’ll see how to create various kinds of

frequency distributions and how to use a frequency distribution to derive additional in-

formation about the scores.

Before we get to that, however, here are some terms and symbols you’ll encounter in

this chapter.

NEW STATISTICAL NOTATION

The scores we initially measure in a study are called the raw scores. Descriptive statistics

help us to “boil down” the raw scores into an interpretable, “digestible” form. There are

several ways to do this, but the starting point is to count the number of times each score

occurred. The number of times a score occurs is the score’s frequency, symbolized by

the lowercase f. (Always pay attention to whether a symbol is upper- or lowercase.) If we

count the frequency of every score in the data, we create a frequency distribution. A

distribution is the general name that researchers have for any organized set of data. As

you’ll see, there are several ways to create a frequency distribution, so we will combine

the term frequency (and f ) with other terms and symbols.

Frequency Distributions

and Percentiles

3

GETTING STARTED

To understand this chapter, recall the following:

■

From Chapter 1, how to calculate proportions and percents.

■

From Chapter 2, the four types of measurement scales.

Your goals in this chapter are to learn

■

What simple frequency, relative frequency, cumulative frequency,

and percentile are.

■

How bar graphs, histograms, and polygons are created.

■

What normal, skewed, bimodal, and rectangular distributions are and how to

interpret them.

■

How relative frequency and percentile are obtained using the area under the

normal curve.

Simple Frequency Distributions 37

In most statistical procedures, we also count the total number of scores. The sym-

bol for the total number of scores in a set of data is the uppercase . An of 10 means

we have 10 scores, or means we have 43 scores. Note that is not the number

of different scores, so even if all 43 scores in a sample are the same score, still

equals 43.

REMEMBER The frequency of a score is symbolized by . The total number

of scores in the data is symbolized by .

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO KNOW ABOUT FREQUENCY DISTRIBUTIONS?

Presenting data in a graph or table is important for two reasons. First, it answers our

question about the different scores that occurred in our data and it does this in an

organized manner. You’ll also see that we have names for some commonly occurring

distributions so that we can easily communicate and envision a picture of even very

large sets of data. Therefore, always create a table or graph of your data. As the saying

goes, “A picture is worth a thousand words,” and nowhere is this more appropriate than

when trying to make sense out of data. Second, the procedures discussed here are im-

portant because they are the building blocks for other descriptive and inferential statis-

tics. (You will be using what you learn here throughout the remainder of this book.)

As you’ll see, we can organize data in one of four ways: using each score’s simple

frequency, relative frequency, cumulative frequency, or percentile.

SIMPLE FREQUENCY DISTRIBUTIONS

The most common way to organize scores is to create a simple frequency distribution.

A simple frequency distribution shows the number of times each score occurs in a set

of data. The symbol for a score’s simple frequency is simply . To find for a score,

count how many times the score occurs. If three participants scored 6, then the

frequency of 6 (its f ) is 3. Creating a simple frequency distribution involves counting

the frequency of every score in the data. One way to see a distribution is in a table.

Presenting Simple Frequency in a Table

Let’s begin with the following raw scores. (They might measure a variable from a cor-

relational study, or they may be dependent scores from an experiment.)

14 14 13 15 11 15 13 10 12

13 14 13 14 15 17 14 14 15

In this disorganized arrangement, it is difficult to make sense out of these scores. See

what happens, though, when we arrange them into the simple frequency table shown in

Table 3.1.

We have several rules for making a frequency table. Start with a score column and an

column. The score column has the highest score in the data at the top of the column.

Below that are all possible whole-number scores in decreasing order, down to the lowest

score that occurred. Thus, the highest score is 17, the lowest score is 10, and although

no one obtained a score of 16, we still include it. Opposite each score in the column is

the score’s frequency: In this sample there is one 17, zero 16s, four 15s, and so on.

f

f

ff

N

f

N

NN 5 43

NN

Score

17 1

16 0

15 4

14 6

13 4

12 1

11 1

10 1

f

TABLE 3.1

Simple Frequency

Distribution Table

The left-hand column identi-

fies each score, and the right-

hand column contains the

frequency with which the

score occurred.