Hatano Y., Katsumura Y., Mozumder A. (Eds.) Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter - Recent Advances, Applications, and Interfaces

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

170 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

Both provide, due to parity violation, a sensitive measure of the interactions of the muon spin with

its environment (Walker, 1983; Roduner, 1988, 1993; Kempton et al., 1991; Fleming and Senba,

1992;

Smigla and Belousov, 1994; Mozumder, 1999; Percival et al., 1999; Johnson et al., 2005).

Studies

on muon interactions with matter in the gas phase are relevant to the elds of atomic,

nuclear, and particle physics; as well as radiation chemistry, hot-atom chemistry, and studies of lin-

ear energy transfer (LET), which is the average energy released per unit path length due to ioniza-

tion

and excitation processes as shown in Mozumder, 1999.

To

maximize the lifetime of materials used in the reaction vessels for applications of radiation,

radiation chemistry in the gas phase needs to be understood. The main purpose of this section is to

review

the thermalization effects and radiation chemistry of positive muons in the gas phase.

There

are some differences in the thermalization processes of electrons and heavy charged par-

ticles in the gas phase, affecting the LET and hence affecting the nature of the radiation effects

involved. The extent of carrier gas decomposition due to ionizing radiation is a strong function of

the absorbed energy density of the incident radiation, with higher LET radiation causing decom-

position of the medium, while low LET radiation leads to little or no decomposition. Differing

LETs and stopping distances can give rise to differences in measured yields of products shown in

Mozumder

(1999).

8.1.2 Muon polarization and itS MeaSureMentS

The initial spin polarization of the μ

+

, at observation times, splits into three principal environments,

depending

on the nature of the stopping medium:

•

Paramagnetic muonium (Mu ≡ μ

+

e

−

) with polarization P

Mu

(Walker, 1983; Smigla and

Belousov,

1994).

•

Diamagnetic molecules, including molecules (like MuH, in water, shown in Percival et al.,

1999 or in hydrocarbons, shown in Kempton et al., 1991) and molecular ions, AMu

+

, where

A

is the molecule of the carrier gas (Johnson et al., 2005), with polarization P

D

.

• Muoniated

free radicals like CH

2

MuCH

2

(Walker, 1983), with polarization P

R

.

In the realm of radiation chemistry, it is important to be able to distinguish between these different

environments (P

Mu

, P

D

, and P

R

) and the timescale of their formation, provided by measurement

of their differing spin precession frequencies in a transverse magnetic eld (TF) (Walker, 1983;

Smigla and Belousov, 1994; Kempton et al., 1991; Percival et al., 1999) or by RF-μSR measurements

in

the work of Johnson et al. (2005).

In

contrast to conventional magnetic resonance studies, where bulk spin polarization is a con-

sequence of differing Boltzmann populations in high magnetic elds, in muon techniques (collec-

tively called μSR) the muon polarization is intrinsic to the probe, and is a direct consequence of

the nuclear weak interaction. Throughout this work, an external static magnetic eld (such as in TF

muon methods) is taken along the positive z-direction B

⃗

= (0, 0, B). The initial muon-spin direction

at

time t

0

= 0 is specied by the direction cosines:

ˆ

( , , ),S

0

cos cos cos= α β γ

0 0 0

(8.1)

where α

0

, β

0

, and γ

0

are the angles between the initial spin and the x-, y-, and z-axes, respectively.

Depending on which component of the muon-spin polarization is measured at observation time,

one can consider the following two congurations separately. In the rst, called the longitudinal

detector/eld conguration, the expectation value of the z component of the muon spin

σ

z

µ

/2

is

the observable quantity, where

σ σ σ σ

µ

µ µ µ

= ( , , )

x y z

represents the Pauli spin matrices for the positive

muon. The second is the transverse detector/eld conguration in which the expectation value of

Muon Interactions with Matter 171

the complex muon-spin polarization in the xy plane,

σ σ σ

µ

µ µ+

= +

x y

i ,

is relevant at observation time,

where

σ

µ

+

is the muon-spin raising operator.

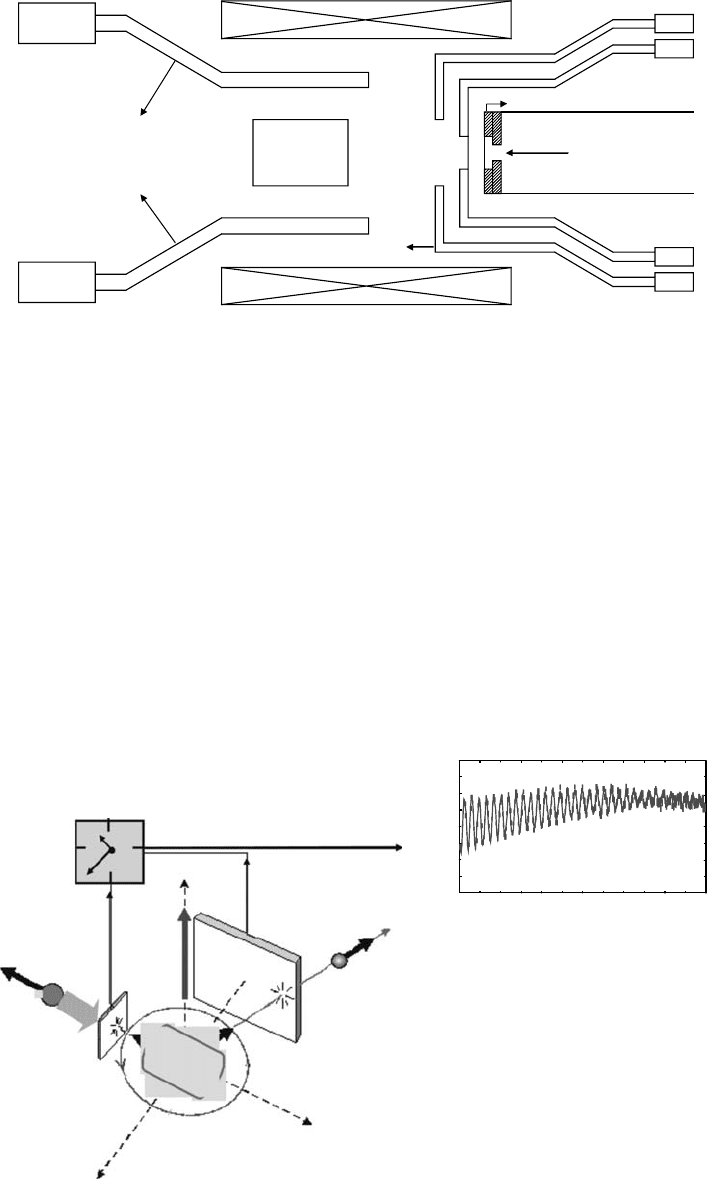

Muon beams enter and stop in the sample vessel. Detectors in coincidence detect muons entering

the sample and positrons emitted when the stopped muons decay. Positron detectors are arranged

around

the sample vessel (Figure 8.1).

In

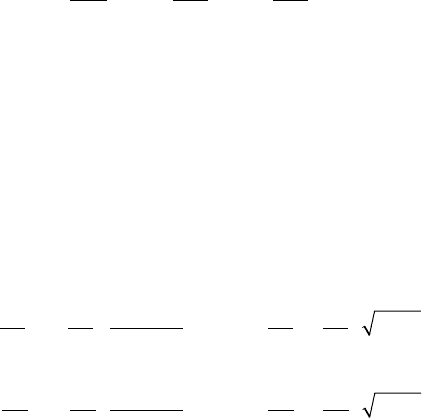

a μSR experiment at a continuous beam facility in the time-differential mode, the elapsed

time between the stop of each muon registered through a muon coincidence (and with a time to

digital converter, TDC) and the detection of its decay positron (stopping the TDC) is measured,

and the data are collected and binned in a histogram of counts as a function of time (Figure 8.2).

In the transverse detector/static eld conguration, the probability of detecting the decay positron

in a given direction varies as the expectation value of the complex muon-spin polarization in the

xy plane oscillates in the magnetic eld. Thus, μSR histograms obtained from each positron detec-

tor contain oscillations in the muon decay spectrum, and these oscillations correspond to the time

dependence

of the muon polarization.

PMT

PMT

Target

vessel

Forward

detector

PMT

PMT

PMT

PMT

Beam pipe

Collimators

Muons

Magnet

Magnet

Backward detector

Figure 8.1 A schematic of the setup for μSR experiments.

Electronic clock

Spin-polarized

muon beam

Muon

detector

H

e

+

μ

+

Sample

Positron

detector

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0

–0.2

–0.1

0.0

0.1

0.2

Asymmetry

Time (μs)

Figure 8.2 A schematic of the setup for TF-μSR experiments.

172 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

Each histogram has the following form:

N t N e A t b

t

( ) ( ) ,

/

= +

+

−

0

1

τ

µ

(8.2)

where

N

0

is an overall normalization that depends on a number of factors, such as the solid angle of the

positron

detectors and the number of stopped muons

b represents random accidental (background) events

τ

μ

= 2.197μs (the muon lifetime)

A(t) represents the “asymmetry,” which represents the μSR signal of interest, and is similar to

free

induction decay (FID) in magnetic resonance

The

asymmetry parameter includes contributions from all muon environments, paramagnetic

Mu and free-radical species, as well as diamagnetic species:

A t A t w t

i i i i i

( ) exp( )cos( ),= − +Σ λ ϕ (8.3)

where

A

i

is the initial amplitude of the muon fraction i in a given environment

λ

i

is the relaxation rate of the muon spin in that environment

w

i

is the corresponding precession frequency

φ

i

is the initial phase for this fraction

The diamagnetic muon relaxation rate is invariably slow enough to be ignored in studies of Mu

reactivity.

The parameters of interest (A

i

, λ

i

, and w

i

) are extracted from ts of Equations 8.2 and 8.3 to

experimental data and give information, respectively, on Mu formation, kinetics, and hyperne

interactions

(in Mu or muoniated radicals), depending on the focus of a given experiment.

The

total (nonrelativistic) Hamiltonian describing the isotropic hyperne and Zeeman interac-

tions

of the muon and electron spin (in Mu) with an external magnetic eld B

⃗

=

(0,0,B) is given by

H

z z

= −

+

+

⋅

ω

σ

ω

σ

ω

σ σ

µ

µ

µ

2 2 4

0e

e

e

, (8.4)

where

σ⃗

e

represent the Pauli spin matrices for the electron

ω

0

/2π is the Mu hyperne frequency

the quantity ω

e

is dened by ω

e

= γ

e

B in terms of the gyromagnetic factor γ

e

of the electron

γ

e

/2π= 28.02421GHz/T

the

quantity ω

μ

is dened by ω

μ

= γ

μ

B in terms of the gyromagnetic factor γ

μ

of the muon

The energy eigenvalues ħω

1

, ħω

2

, ħω

3

, and ħω

4

are labeled in the decreasing order in the low

eld

regime:

ω

ω ω

γ γ

γ γ

ω

ω ω

µ

µ

1

0 0

2

0 0

2

4 2 4 2

1= +

−

+

, = − +

+ ,x x

( )

( )

e

e

ω

ω ω

γ γ

γ γ

ω

ω ω

µ

µ

3

0 0

4

0 0

2

4 2 4 2

1= −

−

+

, = − −

+x x

( )

( )

.

e

e

Muon Interactions with Matter 173

The energy eigenstates ∙1〉, ∙2〉, ∙3〉, and ∙4〉, corresponding to the energy values ħω

1

, ħω

2

, ħω

3

,

andħω

4

, labeled in the decreasing order in the low eld regime, can be expressed as superposition

of

the Mu spin basis set ∙α

μ

α

e

〉, ∙α

μ

β

e

〉, ∙β

μ

α

e

〉, and ∙β

μ

β

e

〉 as

1

2

3

4

1 0 0 0

0 0

0 0 0 1

0 0

=

−

s c

c s

α α

α β

β α

µ

µ

µ

e

e

e

ββ β

α α

α β

β α

β β

µ

µ

µ

µ

µe

e

e

e

e

≡

U , (8.5)

where

c and s are positive parameters dened by

c

x

x

s

x

x

2

2

2

2

1

2

1

1

1

2

1

1

=

+

+

=

−

+

and

in

terms of the reduced magnetic eld

x

B

B

B= =

+

.

0

0

0

with

e

ω

γ γ

µ

By solving the above equation for ∙α

μ

α

e

〉, ∙α

μ

β

e

〉, ∙β

μ

α

e

〉, and ∙β

μ

β

e

〉, one obtains

α α

α β

β α

β β

µ

µ

µ

µ

e

e

e

e

=

−

1 0 0 0

0 0

0 0

0 0 1 0

s c

c s

≡

−

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

1

U . (8.6)

Assuming ϕ

αα

(t), ϕ

αβ

(t), ϕ

βα

(t), and ϕ

ββ

(t) are the Mu spin states that coincide, at t = 0, with ∙α

μ

α

e

〉,

∙α

μ

β

e

〉, ∙β

μ

α

e

〉, and ∙β

μ

β

e

〉, respectively. By using the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, one

canwrite

φ

φ

φ

φ

αα

αβ

βα

ββ

ω

ω

ω

( )

( )

( )

( )

t

t

t

t

U

e

e

e

i t

i t

i

=

−

−

−

−

1

1

2

1

2

33

4

3

4

0 0 0

0 0

0

11

22 23

32 33

t

i t

e

G t

G t G t

G t G

−

=

ω

( )

( ) ( )

( ) (tt

G t

)

( )

,

0

0 0 0

44

α α

α β

β α

β β

µ

µ

µ

µ

e

e

e

e

(8.7)

where

G t e

i t

11

1

( )

= ,

− ω

G t s e c e

i t i t

22

2 2

2 4

( ) ,= +

− −ω ω

G t cse cse G t cse cse

i t i t i t i t

23 32

2 4 2 4

( ) ( ) ,= − , = −

− − − −ω ω ω ω

G t c e s e G t e

i t i t i t

33

2 2

44

2 4 3

( ) ( )= + , = .

− − −ω ω ω

It should be noted that the matrix [G

jk

(t)] is a unit matrix at t = 0: G

jk

(0) = δ

jk

.

174 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

The state in which the spin points in the positive x-direction at time t = 0 is given by

ψ α β

µ µ

( ) ( ).0

1

2

=

+ (8.8)

In magnetic elds <200G, both w

12

and w

23

(w

ij

= w

j

− w

i

) are easily observable, but w

14

and w

34

,

whose parentage is mainly the “singlet” state, are comparable to ω

0

, too fast to be seen, and hence

are averaged to zero by the experimental time resolution. The difference in frequency between

w

12

and w

23

vanishes in elds ∼10G, such that only a single frequency, w

Mu

, is observed. In this limit,

Equation 8.7 reduces to the simple result of coherently precessing “triplet” Mu (Equation 8.3) with

the “Larmor precession,” v

Mu

= 1.39MHz G

−1

. At such a low eld, the diamagnetic Larmor preces-

sion frequency, v

μ

= 13.55kHz G

−1

, cannot be seen over the short time range but shows up charac-

teristically over longer time ranges and at elds ∼20 G. At slightly larger magnetic elds, the spectra

show the fast oscillations and slower beat frequency characteristic of two-frequency Mu precession,

dened by Equations 8.9 and 8.10, and reecting allowed transitions between muon-electron energy

states

in a magnetic eld (Roduner, 1993):

v v v v v A A

12

2 2

1 2

1

2

= − − + +

+

( ) ( ) ,

/

e eµ µ µ µ

(8.9)

v v v v v A A

23

2 2

1 2

1

2

= − + + +

−

( ) ( ) .

/

e eµ µ µ µ

(8.10)

where

v

e

is the electron Larmor frequency

v

μ

the muon Larmor frequency of the coupled two-spin system, with A

μ

the corresponding

muonium

hyperne frequency

The

total Mu amplitudes are most easily found in weak elds, <10G, giving a single amplitude,

while

the diamagnetic amplitudes are usually found from larger elds (Ghandi et al., 2004).

Since

knowing the absolute muon polarization is important, studies are usually rst carried out

in the same sample vessel with a standard sample, usually N

2

for gas phase studies, since the abso-

lute polarizations for N

2

are well established over a wide range of densities as shown in Kempton

et al. (1991). Comparison of the ratio of measured muonium/diamagnetic amplitudes with these

known fractions in N

2

provides a determination both of the diamagnetic signal due to muon stops in

the cell window and walls of the sample vessel, as well as the total muon asymmetry correspond-

ing to the full polarization. The measured amplitudes in the samples of interest are then corrected

according

to established procedures (Roduner, 1993):

P

A A

A A

D

D W

S W

=

−

−

( )

( )

, (8.11)

and

P

A

A A

Mu

Mu

=

−

2

( )

,

S W

(8.12)

Muon Interactions with Matter 175

where

A

D

is the diamagnetic amplitude

A

W

is the sum of the wall and window amplitude

A

S

is the amplitude of the standard (N

2

)

A

Mu

is the muonium amplitude

The

factor 2 in Equation 8.12 accounts for non-observed singlet muonium.

The

initial stage of the energy loss process of any ion in matter is known as the Bethe–Bloch

ionization (Inokuti, 1971; Walker, 1983; Senba, 1988; Roduner, 1993; Smigla and Belousov, 1994;

Pimblott and LaVerne, 1997; Mozumder, 1999; Hatano, 2003; Senba et al., 2006). After passing

through the entrance window of the target cell (Figure 8.1), muons entering the sample still have

the MeV kinetic energies noted earlier, many orders of magnitude higher than those of chemical

interest. Most of this initial energy is dissipated in ionization and excitation processes, described

by the Bethe–Bloch stopping-power formula for −dE/dX (Walker, 1983; Senba, 1988; Smigla and

Belousov, 1994; Mozumder, 1999; Hatano, 2003; Senba et al., 2006). During this regime, there is

no

loss of muon polarization.

In

a low density gas, this is followed by a regime of cyclic charge exchange with moderator “M”

beginning

around 100

keV

for the positive muon and described by

µ

µ

σ

σ

+ +

+ −

+ → +

+ → + +

M Mu M

Mu M M e

10

01

(8.13)

with average electron capture (σ

10

) and loss (σ

01

) cross sections, together with those for elastic and

inelastic energy moderation, determining the outcome as shown in the works of Fleming and Senba

(1992), Kempton et al. (2005), and Senba et al. (2006). In this regime, lasting down to an energy

E

min

∼ 10 eV, the muon undergoes many cycles in less than 1 ns (at 1 atm in the gas phase) as

described in Fleming and Senba (1992); Senba et al. (2006), emerging as either a bare μ

+

or as the

Mu atom, prior to entering its third thermalization stage, from E

min

to k

B

T. Near the end of the cyclic

charge-exchange regime while the muon slows down, one cycle of charge exchange caninvolve

a series of complex collisions, including (1) the electron capture collision by the muonto form

muonium (Mu), (2) repeated spin exchange collisions with paramagnetic species, during the time

the projectile is in the neutral Mu state. This is when there are most likely secondary electrons pres-

ent in the radiation track, and (3) an electron loss collision by Mu to form μ

+

again.

The times taken by positive muons to slow down from initial energies in the range of ∼1 MeV, to

the energy of the last muonium formation, approximately 10eV, at the end of cyclic charge exchange,

have been measured in the pure gases H

2

, N

2

, Ar, and in the gas mixtures Ar-He, Ar-Ne, Ar-CF

4

,

H

2

-He, and H

2

-SF

6

as shown by Senba et al. (2006). At 1atm pressure, these slowing-down times,

in Ar and N

2

, vary from 14ns at the highest initial energy of 2.8MeV, to 6.5ns at 1.6MeV. Similar

variations were seen in the gas mixtures, depending also on the total charge and nature of the mix-

ture consistent with Bragg’s additivity rules. The slowing-down times were also used to determine

the

stopping powers, dE/dX, of the positive muon in N

2

, Ar, and H

2

, at kinetic energies near 2MeV.

The results demonstrated that the positive muon and proton have the same stopping power at the

same projectile velocity, as expected from the Bethe–Bloch formula (Hatano, 2003). The energy of

the rst neutralization collision that forms muonium (hydrogen), which initiates a series of charge-

exchanging collisions, was also calculated for He, Ne, and Ar. The slowing-down times through

the rst two regimes are controlled by the relevant ionization and charge-exchange cross sections,

whereas the nal thermalization regime is most sensitive to the forwardness of the elastic scatter-

ing cross sections in the low density gas phase. In this regime, the slowing-down times (to kT) at

nominal pressures are expected to be less than or similar to 100ns. In this nal stage of energy loss,

176 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

Mumay undergo hot-atom reactions and the μ

+

as well may continue to form Mu by charge exchange

and/or form muon molecular ions, MMu

+

, both in competition with elastic and inelastic scattering.

Although most studies of diamagnetic and muonium (Mu) fractions formed in low pressure gases

have used transverse eld-μSR (TF-μSR) that provides information on sub-microsecond radiation

processes, these studies have recently been extended to the microsecond timescale using the tech-

nique

of time-delayed radio frequency muon-spin resonance (RF-μSR) in Johnson et al. (2005).

In

the RF technique, a static magnetic eld, B, is applied collinearly with the muon-spin polar-

ization, with an oscillating B

1

eld applied transversely to it. Similar to NMR, adjusting the static

eld strength and RF frequency to meet the resonance condition for the system causes the probe

spin polarization to experience a torque and precesses about the B

1

eld for its duration. μSR data

are

collected with and without the RF eld. The experiment alternates between the two conditions,

typically every 10s, to identify the effect of the RF eld on the system and reduce the effects due to

equipment

instability (Johnson et al., 2005).

Results

obtained with inert gases (nitrogen and noble gases) at pressures higher than 1atm estab-

lished the validity of the TF-μSR results, proving that formation of these species is due only to

prompt processes (sub-nanosecond timescale) resulting from charge-exchange and thermalization

processes from keV to epithermal energies. The result was also consistent with the view that the

diamagnetic environment is due to a muon molecular ion, MMu

+

, and not a bare μ

+

. The coupling

between the μ

+

and the gas suggested that the MMu

+

molecular ion is a stable species with no con-

version to a bare μ

+

. In addition, this work showed that the RF-μSR technique provides polarization

fractions in good accord with those obtained using conventional transverse-eld muon-spin reso-

nance

measurements. This is a result that will no doubt be exploited in the years to come.

8.1.3 free-radical forMation in the gaS phaSe

The identity (i.e., the molecular structure) of muoniated free radicals is usually unambiguous,

provided hyperne constants can be determined by TF-μSR or RF-μSR, and avoided level

crossing (μALCR). The spin polarization of the muon beam is perpendicular to the applied

magnetic eld for the TF-μSR experiments, perpendicular during the RF radiation and RF-μSR

experiments, and parallel to the eld for avoided level crossing-μSR (ALC-μSR) experiments

(Roduner, 1988, 1993; Smigla and Belousov, 1994). Positron counters are positioned appropri-

ately in each case.

The precession frequency of the spin in the TF-μSR varies as a function of the strength of the

magnetic eld and the electronic environment, through the hyperne interaction. At high magnetic

elds where Zeeman states are sufciently separated, only two transitions, v

12

and v

34

, are observ-

able (Roduner, 1988, 1993). Fourier transformation of the time spectrum shows three frequency

peaks, two of which correspond to the generated radical (v

12

and v

34

) and one to muons in a dia-

magnetic environment (v

d

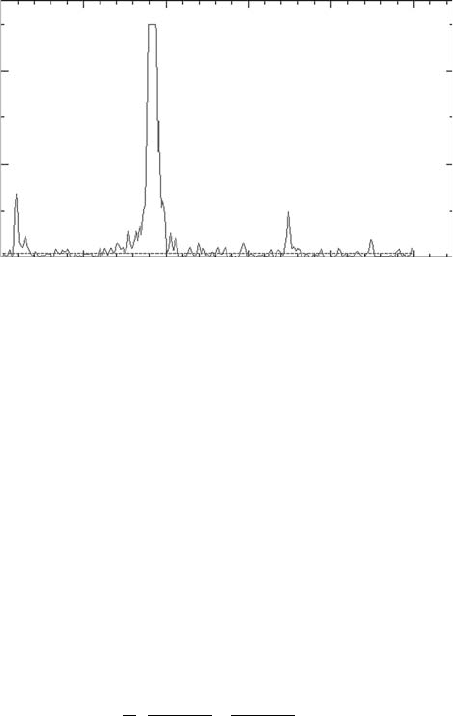

). The spectrum in Figure 8.3 is due to the muoniated ethyl radical in CO

2

(Cormier

et al., 2008).

At

high magnetic elds all energy transitions degenerate to only two, and the associated two

frequencies can be used to determine the muon hyperne coupling constant (HFC), A

μ

according

to

(Roduner, 1988, 1999):

ν ν

µ µij

A= ± ½ ,

(8.14)

where ν

μ

is the muon Larmor frequency. The HFC is proportional to the unpaired spin density at

the

nucleus.

It

is possible to observe “delayed species” that are formed up to 1 μs following muon implanta-

tion using ALC-μSR, and this makes it feasible to study samples with low concentrations of the

free-radical precursors. The spin states in large magnetic elds are the products of the unpaired

Muon Interactions with Matter 177

electron and the nuclear Zeeman states; consequently, the muon spin is time independent and the

asymmetry is independent of the applied magnetic eld. At different values of the applied mag-

netic eld, near-degenerate pairs of spin states can be mixed through the isotropic and anisotropic

components of the hyperne interaction. The muon polarization oscillates between the two mix-

ing states of the avoided crossing. This results in a resonant-like change in the asymmetry as the

magnetic eld is swept. There are three kinds of resonances, classied by the selection rule ∣ΔM∣=

0, 1, and 2, where M is the sum of the quantum numbers for the z components of the muon and

nuclear spins.

In the case of isotropic environments (∣ΔM∣ = 0), once the muon HFC is known using the TF-μSR

technique, proton HFC (A

p

) or the hyperne coupling constants of other spin-active nuclei can be

obtained

from ALC-μSR measurements through the following equation (Roduner, 1988, 1993):

B

A A A A

LCR

p

p

p

e

=

−

−

−

+

1

2

µ

µ

µ

γ γ γ

, (8.15)

where

B

LCR

is the magnetic eld on resonance

γ

p

and γ

e

are the proton and electron gyromagnetic ratio, respectively

In ALC-μSR experiments, the muons are injected into the sample with their spin parallel to the

magnetic eld. The integrated number of positrons emitted in the forward and backward directions

with regard to the incoming muon beam is measured as a function of the applied magnetic eld.

The muon polarization is proportional to the experimental asymmetry. In contrast to TF-μSR, there

is no limit on the number of muons in the sample at one time; consequently, it is possible to run at

a high incident muon rate. The eld is scanned in a series of small steps. It is possible to do both

TF-μSR and ALC-μSR experiments on the same spectrometer, just by moving the counters and

changing the beam polarization. Sometimes a modulation eld (∼80G) is applied to compensate for

the background. This gives the resonance a differential lineshape; however, this is only useful for

studies

of isotropic environments where the resonances are not very wide.

Despite

the superiority of μSR to characterize free radicals (Dilger et al., 1997) and their

electronic structure in the gas phase (polyatomic radicals are generally not amenable to study by

electron spin resonance in the gas phase), gas phase studies of free radicals over the last 10 years

were not very productive. However, there has been an important study on the mechanism of the

muoniated

ethyl radical formation in the gas phase by Percival et al. (2003).

v

34

500400300200

Frequency (MHz)

0

2×10

–4

4×10

–4

Fourier power

1000

v

12

Figure 8.3 The TF-μSR spectra of ethyl radical in a low concentration ethene in supercritical CO

2

at 305K

at

85 bar.

178 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

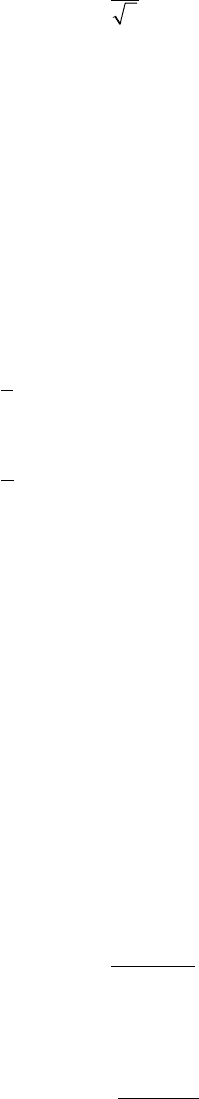

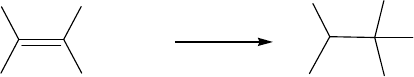

The study tackled the following questions: Is muonium formation the rst step, followed by

addition to the alkene (Figure 8.4)? Or is there an ionic process, such as muon attachment to give

a cation, followed by electron addition? The work in reference Percival et al. (2003) explored such

questions by studying how the spin polarizations of the incident muons were transferred to the

radical product. It was possible to t the TF-μSR signal amplitudes with a model involving a single

reaction step—Mu addition to ethene. However, the rate constant deduced from the model t was

signicantly higher than the literature value for a thermal reaction (Garner et al., 1990), as deter-

mined by direct study of Mu decay in low partial pressures of ethene. The conclusion was that at

partial pressures above 1bar, the reaction (Figure 8.4) occurs before the incoming (beam) muons

are fully thermalized, that is, via a hot-Mu reaction. Comparing the experimental rate constant for

Mu + ethene with the predictions of canonical variational transition state theory (Villa et al., 1998)

suggested that Mu would have an effective temperature of about 2000K, that is, ∼0.25eV kinetic

energy. Using the reactive cross section from the thermal reaction (Garner et al., 1990) and adjusting

for epithermal energies, as shown by Senba et al. (2000), led to 4000K as an estimate of an effec-

tive reaction temperature (∼0.5eV). The rst-order muonium decay rate is 7–50 × 10

9

s

−1

, depending

on ethene pressure, and therefore the reaction timescale is of the order 10–100ps. This meant Mu

could still be epithermal; tens of picoseconds after energetic muons entered the gas at pressures

below 10 bar. This is consistent with expectations based on measurements of muon thermalization

in low pressure gases by Senba et al. (2006), where the slowing-down time to ∼10eV is of the order

of 10ns at 1 bar.

8.2 muon radiation Chemistry in moleCular liQuids

There is consensus about the mechanism of muon thermalization in the gas phase, due to the sim-

plicity of the low density gas phase interactions. However, structures are more complex in the liquid

phase and there is no consensus regarding radiation chemistry in molecular liquids. There have

been several theoretical and experimental studies of liquid muon radiation chemistry over the last

10

years, especially in muonium formation in liqueed inert gases.

The

spatial distribution of electron–muon pairs in superuid helium (He-II) was determined the-

oretically for reconstructing the muonium (Mu) formation probability by Kosarev and Krasnoperov

(1999). It was shown that because a gap is present in the excitation spectrum of He-II, the thermal-

ization time of muons and secondary electrons increases with decreasing temperature. As a result,

the average distance in the electron–muon pairs increases and, correspondingly, the muonium for-

mation rate decreases (Kosarev and Krasnoperov, 1999). Such theoretical predictions of radiolysis

effects in molecular liquids during muon thermalization were later put on rm ground using the

technique of muon-spin relaxation in frequently reversed electric elds (Eshchenko et al., 2000,

2001,

2002, 2003). Such experiments proved that the excess electrons liberated in the μ

+

ionization

track converge upon the positive muons and form Mu atoms. This process was shown to be cru-

cially dependent upon the electron’s interaction with its environment (i.e., whether it occupies the

conduction band or becomes localized) and upon its mobility in these states (Eshchenko etal., 2000,

2001). The characteristic lengths involved are quite long and in the range of 10

−6

−10

−4

cm; the char-

acteristic times range from nanoseconds to tens of microseconds. At the nanosecond timescale, the

Mu+

H

H

α

Mu

H

β

H

β

H

HH

H

•

•

Figure 8.4 Reaction of the muonium with ethene to produce the muon-substituted ethyl radical.

Muon Interactions with Matter 179

thermalization timescale is similar to the gas phase thermalization time but the longer timescales

are

much longer than in the gas phase.

In

general, there have been two types of theoretical (computational) modeling of muon thermal-

ization in molecular liquids. One type is based on electron number density calculations (Kosarev

and Krasnoperov, 1999; Gorelkin et al., 2000) and is similar to the kinetic theory of plasma, while

the other one is based on a stylized initial track structure comprised of many ion pairs, where

the trajectory of each charged particle is followed under the competing inuences of Coulomb

forces and Brownian diffusion (Siebbeles et al., 1999, 2000). Both types of studies are limited to

the low permittivity liquids, where Coulomb forces are long range. The later works of Siebbeles

et al. (1999, 2000) were on liquid hydrocarbons that had accessible electron mobility and electron

thermalization distances. The former works were on liquid rareed gases by Gorelkin et al. (2000)

and Kosarev and Krasnoperov (1999). The studies on liquid hydrocarbons suggested that delayed

muonium formation could account entirely for the missing polarization or lost fraction (Siebbeles

etal., 1999, 2000), P

L

= 1−P

Mu

−P

D

in the absence of free-radical formation, as opposed to the inter-

action of Mu with solvated electrons in the spur from the muon radiation track. For liquids with no

unsaturated bonds, P

R

= 0 because free radicals are not formed. For most saturated hydrogenated

materials, P

L

has been found to be similar in magnitude to P

Mu

according to Walker et al. (2003a,b).

Such theoretical studies set the stage for both experimental and more advanced theoretical inves-

tigation of muon radiolysis effects. The theoretical extension is certainly necessary, in particular a

computational study where the track structure and radiation chemical kinetics simulation would be

extended to include charge cycling, muon trapping as RMu where R is the alkyl radical, and the

effect of the R group on trapping, hot muonium formation, and hot muonium reactions.

There have been preliminary experimental tests carried out by Walker et al. (2003a,b) of the theo-

retical predictions of the radiolysis processes in hydrocarbons performed by Siebbeles et al. (1999,

2000). In the experiments that were carried out by Walker et al. (2003a,b), instead of using Equations

8.6 and 8.7, which is the most accurate way to study the diamagnetic and Mu fraction, the computer-

tted A

D

values were converted to fractional muon yields, P

D

, using P

D(x)

= (A

D(x)

/A

D(water)

) × 0.62, based

on the diamagnetic yield in water of 0.62. Although such a method does not give a denitive test of the

delayed muonium formation predicted by Siebbeles et al. (1999, 2000), the experimental results suggest

that muonium forms on a much shorter timescale than the proposed delayed mechanism (microseconds)

for a fraction of formed Mu. Certainly a more accurate measurement of both diamagnetic and muonium

fractions, a study of magnetic and electric eld dependence and the effect of scavengers on both Mu and

diamagnetic fractions, and RF-μSR investigation of liquid hydrocarbons are needed as denitive tests

of the theoretical studies by Siebbeles et al. (1999, 2000). Such studies are also useful to distinguish

between the spur and hot-atom models in liquids. Indeed, if electron–muon (or muoniated molecular

ion) recombination has a signicant role in muonium formation, the muonium amplitude in a transverse

magnetic eld could be magnetic eld-dependent. Such investigations along with the measurements of

muon polarizations as a function of electric eld, RF, and laser frequencies and delay times will be use-

ful to shed light on mechanism of muon thermalization in molecular liquids.

Two things that are agreed upon regarding the muon thermalization process in liquids between sci-

entists (radiolysis model proponents such as Roduner, 1988; Kosarev and Krasnoperov, 1999; Percival

et al., 1999; Siebbeles et al., 1999; vs. hot-atom model proponents such as Walker, 1983; Walker et al.,

2003a,b) are that (1) the initial stage of the thermalization is ionization and excitation, and (2) the charge-

exchange process (Equation 8.8) follows the established understanding of radiolysis in molecular liq-

uids, where, when a charged particle (except for electrons of energy >100MeV) is being thermalized, it

loses energy by ionizing and exciting the molecules of the medium (Salmon, 2003).

The question now is, what is the thermalization process after this initial stage? There are two

schools of thought. One suggests the nal thermalization steps are only due to hot-atom reactions

of Mu* that determine the nal diamagnetic and muonium fractions proposed by Walker (1983)

and Walker et al. (2003a,b). The other school of thought is based on ionic processes that may arise

at the end of the radiation track (Eshchenko et al., 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003; Ghandi et al., 2007).