Hassani S. Mathematical Methods: For Students of Physics and Related Fields

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

380 Flux and Divergence

where in the last integral we have emphasized the dependence of various quan-

tities on location and time. Now, if Q is a conserved quantity such as energy,

momentum, charge, or mass,

10

the amount of Q that crosses S outward (i.e.,

the flux through S) must precisely equal the rate of depletion of Q in the

volume V .

global or integral

form of continuity

equation

Theorem 13.2.5. In mathematical symbols, the conservation of a conserved

physical quantity Q is written as

dQ

dt

= −

##

S

J

Q

· da, (13.21)

which is the global or integral form of the continuity equation.

The minus sign ensures that positive flux gives rise to a depletion,and

vice versa. The local or differential form of the continuity equation can be

obtained as follows: The LHS of Equation (13.21) can be written as

dQ

dt

=

d

dt

##

V

#

ρ

Q

(r,t) dV (r)=

##

V

#

∂ρ

Q

∂t

(r,t) dV (r),

while the RHS, with the help of the divergence theorem, becomes

−

##

S

J

Q

·da = −

##

V

#

∇ · J

Q

dV.

Together they give

##

V

#

∂ρ

Q

∂t

dV = −

##

V

#

∇ · J

Q

dV

or

##

V

#

(

∂ρ

Q

∂t

+ ∇ ·J

Q

)

dV =0.

This relation is true for all volumes V . In particular, we can make the volume

as small as we please. Then, the integral will be approximately the integrand

times the volume. Since the volume is nonzero (but small), the only way that

the product can be zero is for the integrand to vanish.

Box 13.2.4. The differential form of the continuity equation is

∂ρ

Q

∂t

+ ∇ · J

Q

=0. (13.22)

local (differential)

form of continuity

equation

10

In the theory of relativity mass by itself is not a conserved quantity, but mass in

combination with energy is.

13.2 Flux Density = Divergence 381

Both integral and differential forms of the continuity equation have a wide

range of applications in many areas of physics.

Equation (13.22) is sometimes written in terms of ρ

Q

and the velocity.

This is achieved by substituting ρ

Q

v for J

Q

:

∂ρ

Q

∂t

+ ∇ · (ρ

Q

v)=0

or

∂ρ

Q

∂t

+(∇ρ

Q

) · v + ρ

Q

∇ · v =0.

However, using Cartesian coordinates, we write the sum of the first two terms

as a total derivative:

∂ρ

Q

∂t

+(∇ρ

Q

) · v =

∂ρ

Q

∂t

+

∂ρ

Q

∂x

,

∂ρ

Q

∂y

,

∂ρ

Q

∂z

·

dx

dt

,

dy

dt

,

dz

dt

=

∂ρ

Q

∂t

+

∂ρ

Q

∂x

dx

dt

+

∂ρ

Q

∂y

dy

dt

+

∂ρ

Q

∂z

dz

dt

=total derivative=dρ

Q

/dt

=

dρ

Q

dt

.

Thus the continuity equation can also be written as

dρ

Q

dt

+ ρ

Q

∇ · v =0. (13.23)

Historical Notes

Aside from Maxwell, two names are associated with vector analysis (completely

detached from their quaternionic ancestors): Willard Gibbs and Oliver Heaviside.

Josiah Willard Gibbs’s father, also called Josiah Willard Gibbs, was profes-

sor of sacred literature at Yale University. In fact the Gibbs family originated in

Warwickshire, England, and moved from there to Boston in 1658.

Gibbs was educated at the local Hopkins Grammar School where he was de-

scribed as friendly but withdrawn. His total commitment to academic work together

with rather delicate health meant that he was little involved with the social life of

the school. In 1854 he entered Yale College where he won prizes for excellence in

Latin and mathematics.

Josiah Willard

Gibbs 1839–1903

Remaining at Yale, Gibbs began to undertake research in engineering, writing a

thesis in which he used geometrical methods to study the design of gears. When he

was awarded a doctorate from Yale in 1863 it was the first doctorate of engineering

to be conferred in the United States. After this he served as a tutor at Yale for

three years, teaching Latin for the first two years and then Natural Philosophy in

the third year. He was not short of money however since his father had died in

1861 and, since his mother had also died, Gibbs and his two sisters inherited a fair

amount of money.

From 1866 to 1869 Gibbs studied in Europe. He went with his sisters and spent

the winter of 1866–67 in Paris, followed by a year in Berlin and, finally spending

1868–69 in Heidelberg. In Heidelberg he was influenced by Kirchhoff and Helmholtz.

Gibbs returned to Yale in June 1869, where two years later he was appointed

professor of mathematical physics. Rather surprisingly his appointment to the pro-

fessorship at Yale came before he had published any work. Gibbs was actually

382 Flux and Divergence

a physical chemist and his major publications were in chemical equilibrium and

thermodynamics. From 1873 to 1878, he wrote several important papers on ther-

modynamics including the notion of what is now called the Gibbs potential.

Gibbs’s work on vector analysis was in the form of printed notes for the use of

his own students written in 1881 and 1884. It was not until 1901 that a properly

published version appeared, prepared for publication by one of his students. Using

ideas of Grassmann, a high school teacher who also worked on the generalization of

complex numbers to three dimensions and invented what is now called Grassmann

algebra, Gibbs produced a system much more easily applied to physics than that of

Hamilton.

His work on statistical mechanics was also important, providing a mathematical

framework for the earlier work of Maxwell on the same subject. In fact his last

publication was Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics, which is a beautiful

account putting statistical mechanics on a firm mathematical foundation.

Except for his early years and the three years in Europe, Gibbs spent his whole

life living in the same house which his father had built only a short distance from the

school Gibbs had attended, the college at which he had studied, and the university

where he worked all his life.

Oliver Heaviside caught scarlet fever when he was a young child and this

affected his hearing. This was to have a major effect on his life making his childhood

unhappy, and his relations with other children difficult. However his school results

were rather good and in 1865 he was placed fifth from 500 pupils.

Academic subjects seemed to hold little attraction for Heaviside, however, and

at age 16 he left school. Perhaps he was more disillusioned with school than with

learning since he continued to study after leaving school, in particular he learnt the

Morse code, and studied electricity and foreign languages, in particular Danish and

German. He was aiming at a career as a telegrapher and in this he was advised

andhelpedbyhisuncleCharles Wheatstone (the piece of electrical apparatus the

Wheatstone bridge is named after him).

Oliver Heaviside

1850–1925

In 1868 Heaviside went to Denmark and became a telegrapher. He progressed

quickly in his profession and returned to England in 1871 to take up a post in

Newcastle upon Tyne in the office of the Great Northern Telegraph Company which

dealt with overseas traffic.

Heaviside became increasingly deaf but he worked on his own researches into

electricity. While still working as chief operator in Newcastle he began to publish

papers on electricity. One of these was of sufficient interest to Maxwell that he men-

tioned the results in the second edition of his Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism.

Maxwell’s treatise fascinated Heaviside and he gave up his job as a telegrapher and

devoted his time to the study of the work. Although his interest and understanding

of this work was deep, Heaviside was not interested in rigor. Nevertheless, he was

able to develop important methods in vector analysis in his investigations.

His operational calculus, developed between 1880 and 1887, caused much con-

troversy. Burnside rejected one of Heaviside’s papers on the operational calculus,

which he had submitted to the Proceedings of the Royal Society, on the grounds that

it “contained errors of substance and had irredeemable inadequacies in proof.” Tait

championed quaternions against the vector methods of Heaviside and Gibbs and

sent frequent letters to Nature attacking Heaviside’s methods. Eventually, however,

his work was recognized, and in 1891 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Whittaker rated Heaviside’s operational calculus as one of the three most important

discoveries of the late nineteenth Century.

13.3 Problems 383

Heaviside seemed to become more and more bitter as the years went by. In 1908

he moved to Torquay where he showed increasing evidence of a persecution complex.

His neighbors related stories of Heaviside as a strange and embittered hermit who

replaced his furniture with granite blocks which stood about in the bare rooms like

the furnishings of some Neolithic giant. Through those fantastic rooms he wandered,

growing dirtier and dirtier, with one exception: His nails were always exquisitely

manicured, and painted a glistening cherry pink.

13.3 Problems

13.1. Using (13.6) find the flux of the vector field A = kx

2

ˆ

e

z

through the

portion of the sphere of radius a centered at the origin lying in the first octant

of a Cartesian coordinate system.

13.2. Using (13.6) find the flux of the vector field A = y

ˆ

e

x

+3z

ˆ

e

y

− 2x

ˆ

e

z

through the portion of the plane x +2y −3z = 5 lying in the first octant of a

Cartesian coordinate system.

13.3. A vector field is given by A = r. Using (13.6) find the flux of this

vector field through the upper hemisphere centered at the origin. Verify your

answer by calculating the flux using (the much easier) spherical coordinates.

13.4. Find the flux of the vector field A = x

2

ˆ

e

x

+ y

2

ˆ

e

y

+ z

2

ˆ

e

z

through the

portion of the plane x + y + z = 1 lying in the first octant of a Cartesian

coordinate system.

13.5. Using (13.6), find the flux of the vector field A = kr/r

3

through the

upper hemisphere centered at the origin. Verify your answer by calculating

the flux using spherical coordinates.

13.6. Find the flux of the vector field A = y

ˆ

e

y

+ a

ˆ

e

z

through the portion of

the paraboloid z = b

2

− x

2

− y

2

above the xy-plane.

13.7. Derive Equation (13.9).

13.8. Find the flux of the vector

A =

6ka

2

y

x

2

+ y

2

+ a

2

ˆ

e

x

+

3ka

2

z

y

2

+ z

2

+4a

2

ˆ

e

y

+

2ka

2

x

√

x

2

+ z

2

+9a

2

ˆ

e

z

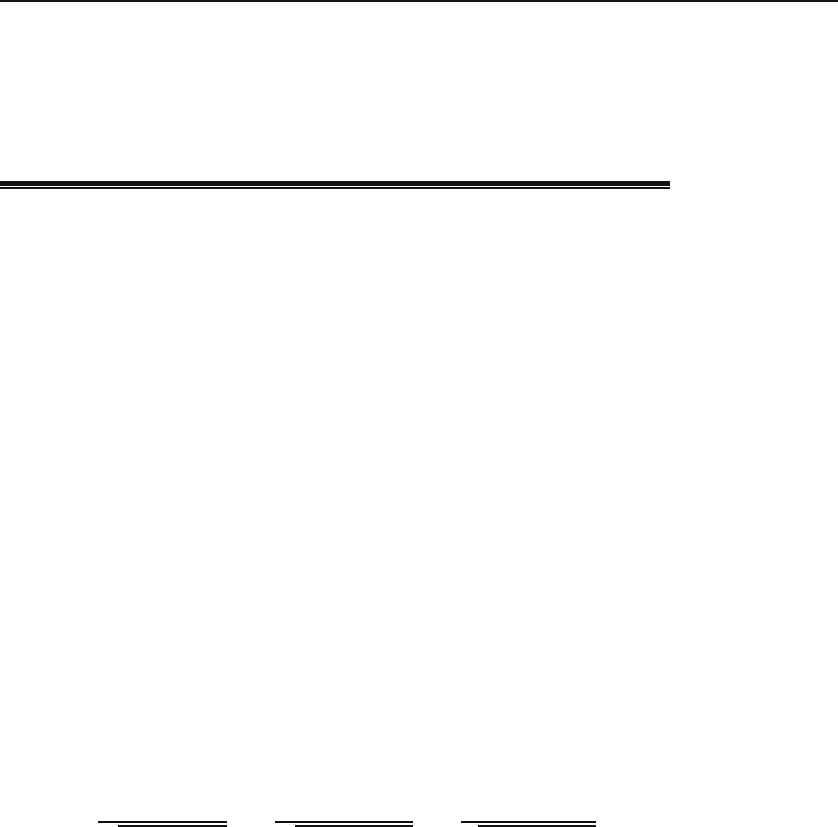

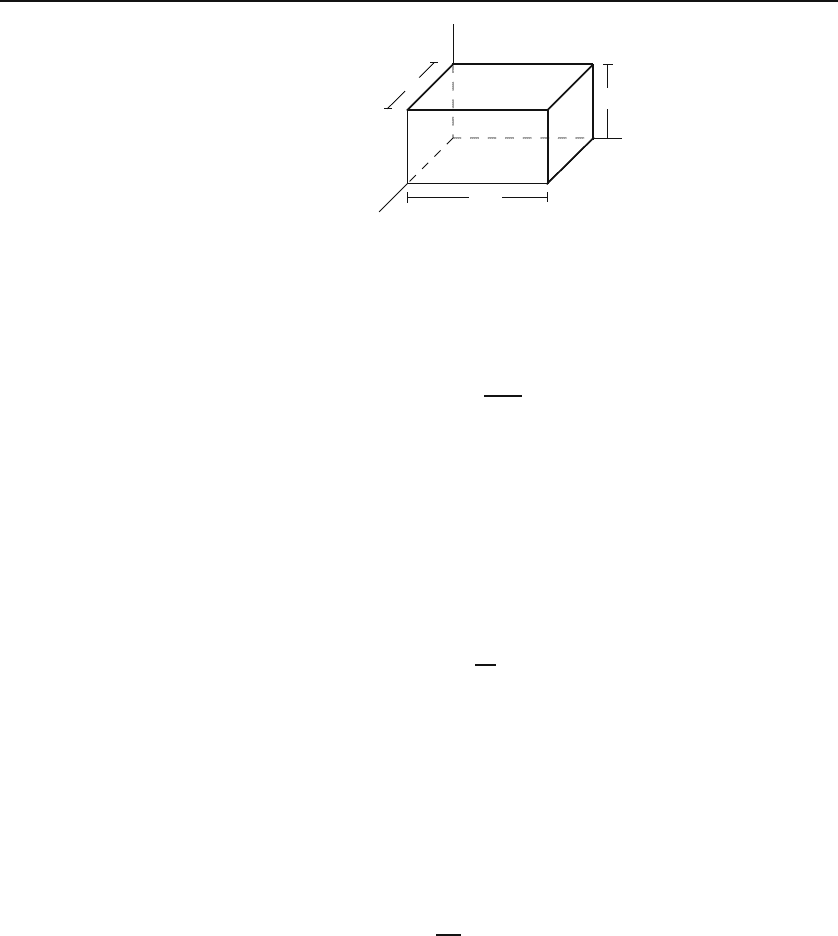

through the surface of the box shown in Figure 13.8:

(a) by integrating over the surface of the box; and

(b) by using the divergence theorem and integrating over the volume of the

box.

13.9. The gravitational field of a certain mass distribution is given by

g(x, y, z)=−kG

,

(x

3

y

2

z

2

)

ˆ

e

x

+(x

2

y

3

z

2

)

ˆ

e

y

+(x

2

y

2

z

3

)

ˆ

e

z

-

,

where k is a constant and G is the universal gravitational constant:

(a) Find the mass density of the source of this field.

(b) What is the total mass in a cube of side 2a centered about the origin?

384 Flux and Divergence

x

y

z

2a

3a

a

Figure 13.8: The box of Problem 13.8.

13.10. The gravitational field of a certain mass distribution in the first octant

of a Cartesian coordinate system is given by

g(x, y, z)=−

GM

a

3

re

−(x+y+z)/a

,

where r is the position vector, M and a are constants, and G is the universal

gravitational constant.

(a) Find the mass density of the source of this field.

(b) What is the total mass in a cube of side a with one corner at the origin

and sides parallel to the axes?

13.11. The electrostatic potential of a certain charge distribution in Cartesian

coordinates is given by

Φ(x, y, z)=

V

0

a

3

xyze

−(x+y+z)/a

,

where V

0

and a are constants.

(a) Find the electric field E = −∇Φ of this potential.

(b) Calculate the charge density of the source of this field.

(c) What is the total charge in a cube of side a with one corner at the origin

and sides parallel to the axes? Write your answer as a numerical multiple of

0

V

0

a.

13.12. The electric field of a charge distribution is given by

E =

E

0

a

4

xyze

−(x+y+z)/a

r.

(a) Write the Cartesian components of this electric field completely in Carte-

sian coordinates.

(b) Calculate the volume charge density giving rise to this field.

(c) Find the total charge in a cube of side a whose sides are parallel to the axes

and one of whose corners is at the origin. Write your answer as a numerical

multiple of

0

E

0

a

2

.

13.3 Problems 385

13.13. The velocity of a physical quantity Q is radial and given by v = kr

where k is a constant. Show that if the density ρ

Q

is independent of position,

then it is given by

ρ

Q

(t)=ρ

0Q

e

−3kt

where ρ

0Q

is the initial density of Q.

Chapter 14

Line Integral and Curl

Last chapter introduced the concept of flux and the surface integral associated

with it. Flux uses the directional property of a vector field to have it pierce an

element of area. The directional property can also naturally assign a varying

direction along a line. One can consider how a vector field changes direction

as it moves along a curve in space. This change can also lead to a new kind of

integration and differentiation of vector fields. The integration leads to the no-

tion of a line integral and the associated differentiation to the concept of curl.

14.1 The Line Integral

The prime example of a line integral is the work done by a force. Consider

the force field F(r) acting on an object and imagine the object being moved

by a small displacement Δr. Then the work done by the force in effecting this

displacement is defined as

ΔW = F(r) ·Δr,

where it is assumed that F(r) is (approximately) constant during the displace-

ment.

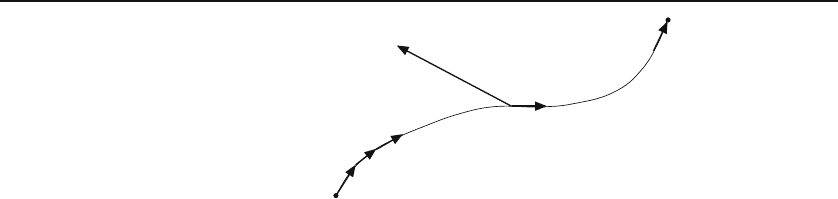

To calculate the work for a finite displacement, such as the one shown

in Figure 14.1, we break up the displacement into N small segments, cal-

culate the work for each segment, and add all contributions to obtain W ≈

N

i=1

F(r

i

) · Δr

i

. The approximation sign can be removed by taking Δr

i

as

small as possible and N as large as possible. Then we have

line integral

defined

W =

#

P

2

P

1

F(r) · dr ≡

#

C

F ·dr, (14.1)

where C stands for the particular curve on which the force is displaced. This

equation is, by definition, the line integral of the force field F.Inthispartic-

ular case it is the work done by F in moving from P

1

to P

2

. Of course, we can

apply the line integral to any vector field, not just force. In electromagnetic

388 Line Integral and Curl

P

1

Δ r

1

Δ r

3

Δ r

2

Δ r

N

Δ r

i

P

2

F(x

i

, y

i

, z

i

)

Figure 14.1: The line integral of a vector field F from P

1

to P

2

.

theory, for example, the line integrals of the electric and magnetic fields play

a central role.

The most general way to calculate a line integral is through parametric

equation of the curve. Thus, if the Cartesian set of parametric equations of

the curve is

x = f(t),y= g(t),z= h(t),

then the components of the vector field A will be functions of a single variable

t obtained by substitution:

A

x

(x, y, z)=A

x

f(t),g(t),h(t)

!

≡ F(t),

A

y

(x, y, z)=A

y

f(t),g(t),h(t)

!

≡ G(t),

A

z

(x, y, z)=A

z

f(t),g(t),h(t)

!

≡ H(t),

and the components of dr are

dx = f

(t) dt, dy = g

(t) dt, dz = h

(t) dt.

Then the line integral of A can be written as

line integral in

terms of the

parametric

equations of the

curve

#

C

A ·dr =

#

C

(A

x

dx + A

y

dy + A

z

dz)

=

#

b

a

,

F(t)f

(t)+G(t)g

(t)+H(t)h

(t)

-

dt, (14.2)

where t = a and t = b designate the initial and final points of the curve,

respectively. Other coordinate systems can be handled similarly. Instead of

giving a general formula for these coordinate systems, we present an example

using cylindrical coordinates.

Example 14.1.1.

Consider the vector field given by

A = c

1

zϕ

ˆ

e

ρ

+ c

2

ρz

ˆ

e

ϕ

+ c

3

ρϕ

ˆ

e

z

,

where c

1

, c

2

,andc

3

are constants. We want to calculate the line integral of this

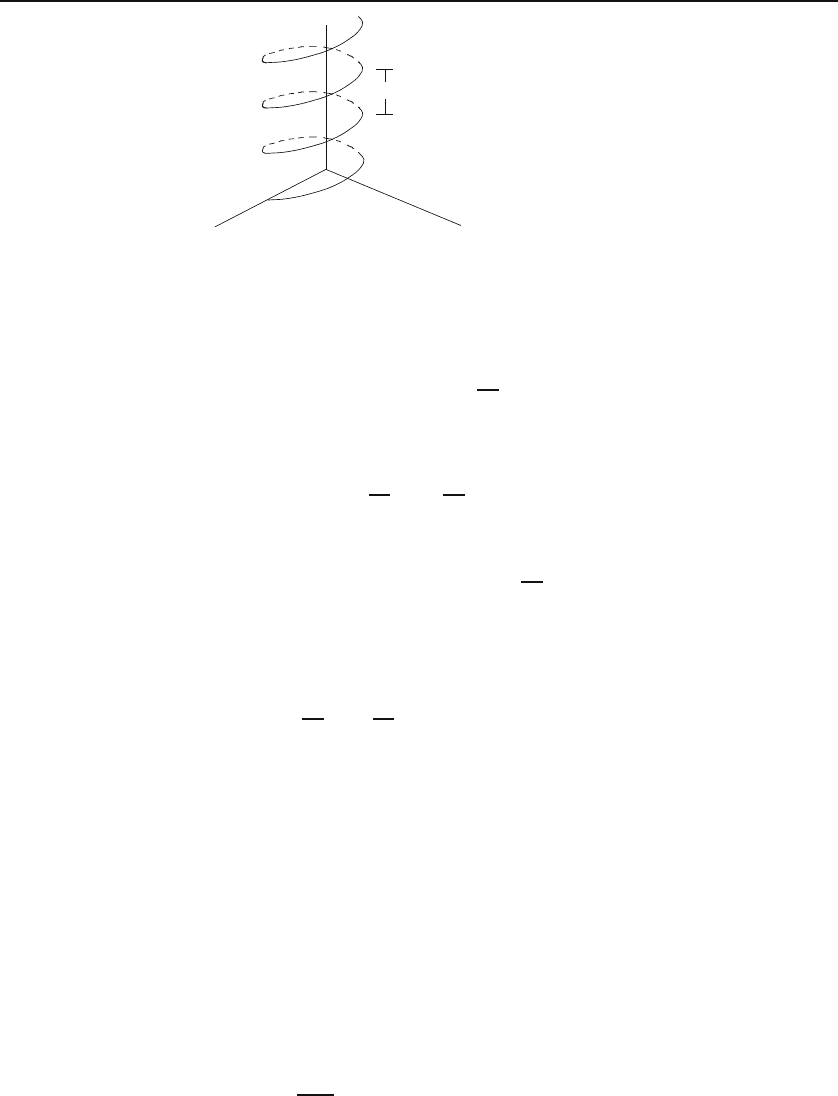

field, starting at z = 0, along one turn of a uniformly wound helix of radius a whose

14.1 The Line Integral 389

x

y

z

b

Figure 14.2: The helical path for calculating the line integral.

windings are separated by a constant value b (see Figure 14.2 ). The parametric

equation of this helix in cylindrical coordinates is

ρ ≡ f (t)=a, ϕ ≡ g(t)=t, z ≡ h(t)=

b

2π

t.

Notice that as ϕ = t changes by 2π, the height (i.e., z) changes by b as required.

Substituting for the three coordinates in terms of t in the expression for A,weobtain

A ≡F(t), G(t), H(t) =

c

1

b

2π

t

2

,c

2

a

b

2π

t, c

3

at

.

Similarly,

dr = dρ, ρ dϕ, dz = f

(t),f(t)g

(t),h

(t)dt =

0,a,

b

2π

dt,

so that

#

C

A · dr =

#

b

a

,

F(t)f

(t)+G(t)g

(t)+H(t)h

(t)

-

dt

=

#

2π

0

(

0+c

2

a

2

b

2π

t + c

3

b

2π

at

)

dt = πab(c

2

a + c

3

).

Example 14.1.2. Consider the vector field A = K(xy

2

ˆ

e

x

+ x

2

y

ˆ

e

y

). We want

to evaluate the line integral of this field from the origin to the point (a, a)inthe

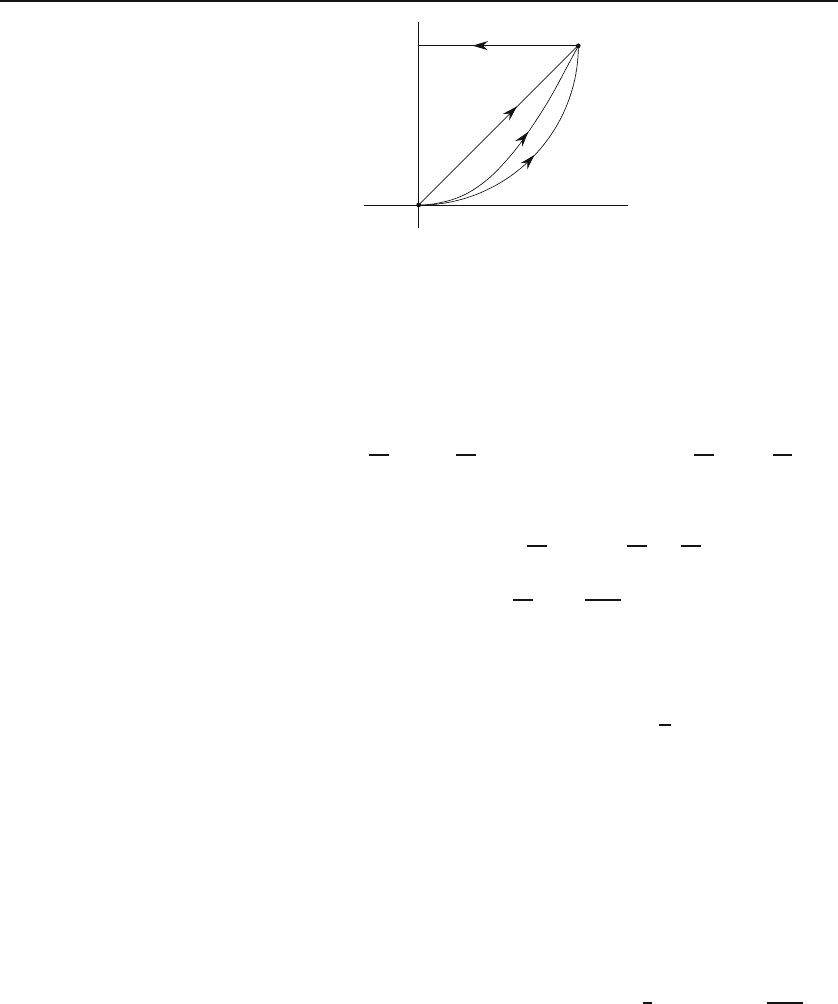

xy-plane along three different paths (i), (ii), and (iii), as shown in Figure 14.3. Since

the vector field is independent of z and the paths are all in the xy-plane, we ignore

z completely.

The first path is the straight line y = x. A convenient parameterization is x = at,

y = at with 0 ≤ t ≤ 1. Along this path the components of A become

A

x

= Kxy

2

= K(at)(at)

2

= Ka

3

t

3

,A

y

= Kx

2

y = K(at)

2

(at)=Ka

3

t

3

.

Furthermore, taking the differentials of x and y,weobtaindx = adt and dy = adt.

Thus,

#

C

A · dr =

#

(a,a)

(0,0)

(A

x

d

x

+ A

y

d

y

)=K

#

1

0

.

a

3

t

3

!

adt+

a

3

t

3

!

adt

/

=2Ka

4

#

1

0

t

3

dt =

Ka

4

2

.

390 Line Integral and Curl

x

y

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

(a, a)

(iv)

Figure 14.3: The three paths joining the origin to the point (a, a).Path(iv)isto

illustrate the importance of parameterization.

Although parameterization is very useful, systematic, and highly recommended,

it is not always necessary. We calculate the line integral along path (ii)—given by

y = x

2

/a—without using parameterization. All we have to notice is that all the y’s

are to be replaced by x

2

/a [and therefore, dy by (2x/a) dx]. Thus,

A

x

= Kxy

2

= Kx

x

2

a

2

= K

x

5

a

2

,A

y

= Kx

2

y = Kx

2

x

2

a

= K

x

4

a

.

The line integral can now be evaluated easily:

#

(a,a)

(0,0)

(A

x

d

x

+ A

y

d

y

)=K

#

a

0

x

5

a

2

dx +

x

4

a

2x

a

dx

=3K

#

a

0

x

5

a

2

dx =

Ka

4

2

.

Finally, we calculate the line integral along the quarter of a circle. For this calcu-

lation, we return to the parameterization technique, because it eases the integration.

A simple parameterization is

x = a −a cos t, y = a sin t, 0 ≤ t ≤

π

2

,

with dx = a sin tdt and dy = a cos tdt. This yields

A

x

d

x

+ A

y

d

y

= K[(a − a cos t)a

2

sin

2

t]a sin tdt+ K[(a − a cos t)

2

a sin t]a cos tdt

= Ka

4

[(1 − cos t)(1 − cos

2

t)+(1− cos t)

2

cos t]sintdt

= Ka

4

(1 − 3cos

2

t +2cos

3

t)sintdt.

This is now integrated to give the line integral:

#

(a,a)

(0,0)

(A

x

d

x

+ A

y

d

y

)=Ka

4

#

π/2

0

(1 − 3cos

2

t +2cos

3

t)sintdt

= Ka

4

−cos t

π/2

0

+cos

3

t

π/2

0

−

1

2

cos

4

t

π/2

0

=

Ka

4

2

.

The fact that the three line integrals yield the same result may seem surprising.

However, as we shall see shortly, it is a property shared by a special group of vector

fields of which A is a member.