Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 16

Athens in the fifth century BC

The fifth century BC marked the high point of Athens, with extraordinary achievements in litera-

ture, architecture, and visual arts matched by political power and wealth. Its only rival for lead-

ership of the Greek world was Sparta, always militarily strong. This dominance would be brief.

Although Athens continued as an intellectual center in the fourth century BC and indeed beyond,

defeat at the hands of the Spartans in 404 BC and the dissolution of her empire at the end of the

long Peloponnesian War ended both her power and the profits reaped from the states once sub-

ject to it. In this chapter we shall examine the major material remains of fifth century BC Athens

– the building program on the Acropolis and the Classical Agora – and explore how the Acropolis

monuments, in particular, served to enhance the prestige of the city in this its century of glory.

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

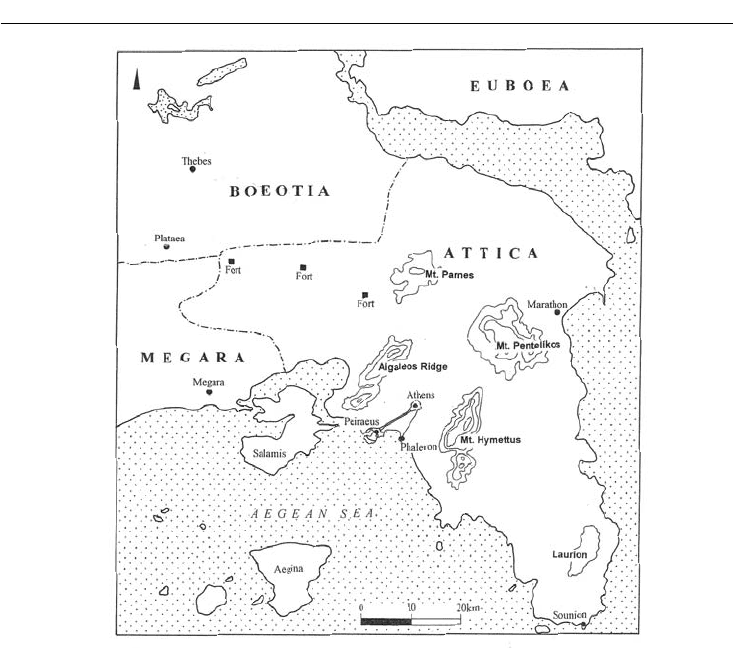

When the Persians retreated after their defeats at Salamis and Plataea, the Athenians returned

to rebuild their city, sacked in 480 BC. Although the Persians had been defeated, no one knew

whether they would regroup and attempt conquest once again. In this climate of uncertainty,

the Athenians decided a strong set of fortification walls was needed. The leading statesman of

the time was Themistokles, whose far-sighted promotion of shipbuilding in the 480s (paid with

silver mined at Laurion, in south-east Attica) had saved Athens from annihilation at the Battle

of Salamis. Under his guidance new walls were quickly erected around Athens and its port of

Peiraeus. Any available stone was used for the lower portions of the walls, including pieces from

destroyed buildings and even sculpted funerary stelai; the upper reaches were made of mud

brick. During the following decades town and port were linked by the Long Walls, a corridor of

parallel walls, with a third wall reaching eastwards to protect the secondary harbor at Phaleron

(Figure 16.1).

Precautions against a Persian return were also undertaken on a larger stage. The Delian League,

formed in 478 BC, was a coalition of states under the leadership of Athens that maintained a large

navy, with states contributing either ships or money. The member states tended to be the coastal

and island cities of the Aegean and the Sea of Marmara. The sacred island of Delos, centrally

located, was selected as the site of the League’s treasury. Periodic battles with the Persians did

Early Classical period: ca. 480–450 BC

High Classical period: ca. 450–400

BC

ATHENS IN THE FIFTH CENTURY BC 253

take place, notably along the south coast of Turkey and in Egypt, but the Persians never seriously

threatened the mainland of Greece or the Aegean islands. Indeed, a formal peace may have been

concluded with the Persians in the middle of the century. Nevertheless, Athens tightened her

grip over the member states, gradually transforming the League into an Athenian empire. The

Persian menace may have receded, but Sparta and her allies presented new challenges. Member

states no longer had the option of furnishing ships. Only money was accepted: a tribute, not a

contribution. Pretences of equality were further stripped when, in 454 BC, the treasury of the

League was moved from Delos to Athens.

According to tradition, before the Battle of Plataea, the Greek city-states had taken an oath

never to rebuild the temples destroyed by the Persians in 480 BC: “Of the shrines burnt and

overthrown by the barbarians I will rebuild none, but I will allow them to remain as a memo-

rial to those who come after of the impiety of the barbarians” (Wycherley 1978: 106, from

Lycurgus, Against Leokrates 80–81). Conspicuous among these ruins were the sacred buildings on

the Athenian Acropolis, the cult center of Athens. By the middle of the fifth century, however,

the Athenians decided to rebuild. The sentiment sworn in the Oath of Plataea seemed irrelevant:

the Persian threat had diminished, and more significantly, Athens had become a major power.

Under the leadership of Perikles, the leading statesman from ca. 461 to 429

BC, the Athenians

expressed their city’s greatness in a major reconstruction of the sanctuary to Athena on the

Acropolis.

Figure 16.1 Attica

254 GREEK CITIES

Athenian ambitions did not go unchallenged. Opponents in central and southern Greece,

including such economic centers as Corinth, persuaded Sparta to lead their cause. War broke out

in 431 BC: the Peloponnesian War. This confrontation between Athens and Sparta and their allies

lasted until 404 BC, ending with a Spartan victory and occupation of Athens and the pulling down

of the Athenian walls. But the war had exhausted Sparta as well; it was unable to capitalize on its

success. In 394 BC, Athens, now freed of Spartan tutelage, rebuilt its walls under the leadership

of Konon and regained a measure of its former importance.

THE ATHENIAN ACROPOLIS

Settlements were usually located with an eye for defense, as we have seen. Coastal towns might

take advantage of peninsulas surrounded by the sea. For cities both coastal and inland, a hill

or mountain top, easily fortified, was desirable; indeed, the term “acropolis,” or “high city” in

Greek, was commonly used throughout the Greek world to designate such a feature. The Acrop-

olis at Athens is thus by no means unique among naturally protected locations in the Greek

world, but it is the best known.

The Athenian Acropolis is a natural broad-topped hill rising 90m above the city below. In the

distance, the plain in which the city lies is enclosed by mountains, sacred elements in the land-

scape – Mount Hymettus with its double horned peak (south-east), Mount Pentelikos (north-

east), Mount Parnes (north-west), and the Aigaleos ridge (west) – and the Aegean Sea (south).

The earliest known use of the hilltop dates to the Bronze Age. Features of the Mycenaean citadel

can still be seen, including a stretch of Cyclopean masonry belonging to the fortification wall.

Only in the Archaic period did the primary function change from fortress to religious sanctu-

ary, with the worship of Athena predominating. During medieval and early modern times, the

Acropolis became a fortified village, the ancient buildings adapted for new needs. Drawings by

western European travelers show us the Acropolis clustered with houses. With the naming of

Athens as the capital of modern Greece in 1833, an intense interest arose in rediscovering the

appearance of the city in Classical times: the newly created country wished to identify itself with

ancient glory. The Acropolis was soon stripped of its medieval and Ottoman accretions; the

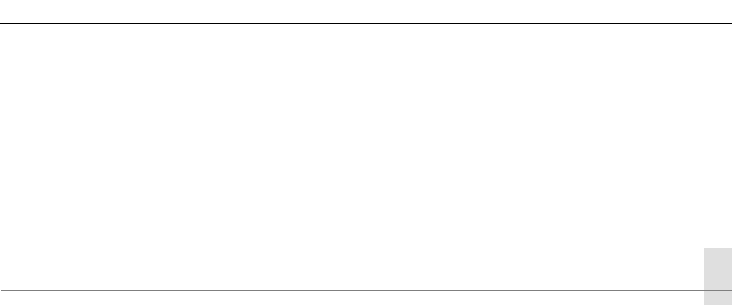

four buildings that dominate the Acropolis today – the Parthenon, the Propylaia, the Temple of

Athena Nike, and the Erechtheion – are all products of the Periklean building program of the

second half of the fifth century BC (Figures 16.2 and 16.3). Major excavations followed in the

later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with Greek and German archaeologists exploring

down to bedrock in order to clarify the architectural history of the site. Reconstruction and con-

servation of the ancient buildings continue to the present day, tasks all the more urgent with the

increasingly destructive air pollution and acid rain of modern industrialized Athens.

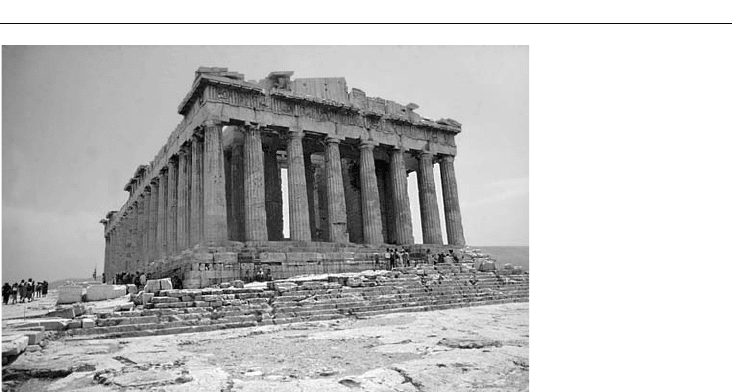

The Parthenon: architecture

The Parthenon, or Temple to Athena Parthenos, Athena in her aspect as warrior maiden, is

the earliest and most important building of the Periklean refurbishing of the Acropolis (Figure

16.4). Although a Doric temple, the Parthenon incorporates several Ionic features, a fusion suit-

able for an empire that now reached across the Aegean to East Greece, the heartland of Ionic

architecture. Its architects were Iktinos and Kallikrates, but its complex sculptural decoration

was the work of Pheidias, who also served as overseer of the entire Acropolis building program.

Built between 447 and 438

BC, the Parthenon was the third temple on the site, replacing a smaller

ATHENS IN THE FIFTH CENTURY BC 255

temple from the mid-sixth century BC and a second, larger building, under construction when

the Persians sacked the Acropolis in 480 BC. Preservation of the Parthenon long after the end

of pagan religion was ensured by the conversion of the temple first into a Christian church,

later into a Muslim mosque. In 1687, however, its center was destroyed in an explosion, when

an artillery shell from attacking Venetians hit gunpowder stored there by the Ottomans. Much

Figure 16.2 Plan, the Acropolis, Athens, fifth century BC

Figure 16.3 The Acropolis (reconstruction), Athens, fifth century BC

256 GREEK CITIES

of the surviving sculptural decoration was removed to Britain in the early nineteenth century

by Lord Elgin; purchased by the government, the sculpture entered the collections of the Brit-

ish Museum. The Parthenon itself has undergone various restorations in modern times, most

recently from the 1980s to the present.

The builders of the Parthenon took advantage of the preparatory work done for the late

Archaic temple destroyed by the Persians. In particular, they reused much of the foundation

platform. Because the new temple was somewhat larger than its predecessor, adjustments had

to be made. The temple lies over the sharp southward slope of the Acropolis bedrock, so on the

south, especially, the foundations had to be built up in many courses in order to provide a level

surface for the temple.

The ground plan of the Parthenon departs from the typical in a few important respects (see

Figure 16.2). The colonnade consists of eight columns on the short sides and seventeen on the

long sides, an expansion of the usual Doric column count that imparts rather the feeling of a

massive Ionic temple. Following the standard Greek procedure of building temples from the

outside in, the colonnade would have been the first portion of the temple erected. From the east,

one passed through a truncated porch (prostyle hexastyle, or six columns, with the end two being

placed in front of the wall ends) into the cella, home of the gold and ivory cult statue made by

Pheidias. A two-storied Doric colonnade, supporting a gallery on the upper floor, framed the

statue behind as well as on the sides in a U-shaped formation. Recent research of Manolis Kor-

res has revealed that the east wall of the cella contained windows on either side of the doorway;

the cella and the cult statue were hence better lit than previously thought. A second room lay

adjacent to the cella on the west. This room, entered from the truncated porch on the west, was

called the Parthenon, the chamber of the virgin, but apparently served as a treasury rather than

as the home of a cult statue. Two, or perhaps four, Ionic columns held up the roof. Since the

proportions of Ionic columns could be taller and slenderer than Doric, there was no need for a

second tier in order to reach the roof beams.

The elevation of the temple follows the arrangement expected for the Doric order. Since

no expense was spared, the temple was decorated with sculpted metopes on all four sides, and

sculpted pediments. Unusual, however, is the addition of a sculpted frieze, an Ionic feature, high

inside the colonnade, on the top of the exterior walls of the cella, the Parthenon, and the two

truncated porches.

Figure 16.4 The

Parthenon, seen from

the west

ATHENS IN THE FIFTH CENTURY BC 257

Also unusual are the deviations from strict vertical and horizontal lines and proportional

arrangement, the so-called “refinements.” The stylobate, for example, is not flat, but curves

slightly from the center down to the four corners, as if four people held a sheet by its corners,

billowed it up into the air, then pulled it down slowly. The centers of the long sides are some

10cm higher than the corners. Other “refinements” include the thickening of the corner column

one-fortieth more than the normal column diameter; corner contraction, that is, the setting in

from the corner, in this case a distance of ca. 0.60m, of the corner columns on the short sides;

the slight tilt inward of the columns; the upward tapering of the columns; the leaning inward of

the long walls of the cella; and the slight outward tilt of the entablature and pediments. All of

these variants are measurable and sometimes can be verified with the naked eye. Many have been

observed on earlier and later temples, in particular Doric rather than Ionic, but nowhere else

have they all been combined as here. The precise carving of the appropriate blocks must have

required much additional time. Why the bother?

The purpose of these deviations has been much debated. Vitruvius, the Roman architect, who

had consulted a book about the Parthenon by Iktinos and Karpion, proposed that the architects

compensated for anticipated optical illusions. Since a long horizontal line seems to sag, it should

look perfectly horizontal if its middle is raised. Modern commentators have made other sugges-

tions. Perhaps the curve of the stylobate is actually perceived as more pronounced, a deliberate

exaggeration that makes the stylobate appear larger than it really is. A third interpretation, which

correlates well with intellectual trends in Classical Athens, favors the tension created between

expectations and appearances: one expects straight lines, but sees (or senses) curves and tilts.

The lines of the building thus never quite explain themselves. The building remains a mystery

that the viewer cannot stop contemplating. The correct answer or answers may be impossible

to find, but in any case, the abundant use of refinements is a mark of the sophistication of the

design of this great temple.

The Parthenon: sculptural decoration and the cult statue

The sculptural decoration of the Parthenon was not simply famously beautiful; it had important

messages to impart. As typical for ancient Greek temples, the exterior carried the figural deco-

ration. The interior was reserved for the cult statue, without additional imagery. The sculpture

illustrated themes that concerned both the city, its patron goddess, Athena, and its religious prac-

tices, and the continuing need for the forces of order and civilization to fight for victory. Absent

are any pictures of the rulers or prominent citizens of Athens. This last feature, a characteristic

of Classical Greek art, contrasts strongly with, for example, the art of the Ancient Near East and

Egypt, in which the divinity and the monarch are habitually shown in beneficial partnership.

This lavish and complex program of sculpture took some time to complete. The metopes were

the first component of the sculptural decoration to be carved, from ca. 447 to 442 BC, followed

by the frieze and the cult statue (both finished by 438 BC, along with the building itself), and finally,

the pedimental sculptures (by 432 BC). This, and other details of the construction of the Parthenon,

we know from building accounts, inscriptions carved on stone which recorded for public appre-

ciation sources of money and exactly for what it was spent.

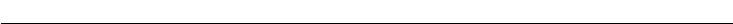

The metopes

All ninety-two metopes contained sculpture. Many were destroyed or damaged in the

explosion of 1687, but enough have survived to give a good idea of subject matter and

258 GREEK CITIES

style. The metopes illustrated the combats of Lapiths vs. Centaurs, Gods vs. Giants, Greeks

vs. Amazons, and probably Greeks vs. Trojans, all allegories for the battle of Order vs. Chaos,

Civilization vs. Barbarism – which for fifth century BC Greeks specifically meant their conflict

with the Persians. The styles vary, indicating

that the design and execution of the metopes

was done by several artists, but all display the

optically realistic treatment of the human body

developed first in late Archaic sculpture and

vase painting (Figure 16.5).

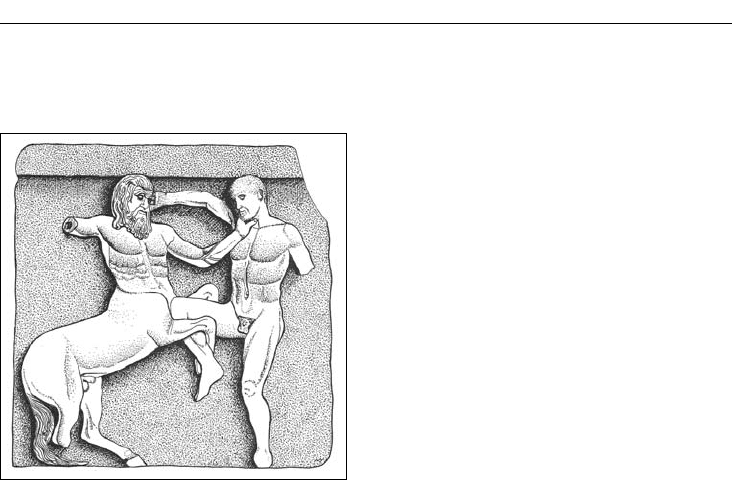

The frieze

The frieze, far better preserved than the other

sculpture, records the procession during the

Panathenaic Festival that led through the city up

to the Acropolis, with the aim of presenting a

newly woven, brightly colored peplos to dress the

venerable cult statue of Athena Polias, Athena

as patron goddess of the city. The Panathenaia,

the most important religious festival of Athens,

was held every year in mid-August (in our cal-

endar) to celebrate the birthday of Athena. Every fourth year a grander version took place, the

Great Panathenaia. The centerpiece of this quadrennial procession was a monumental peplos

displayed like a sail on a ship pulled on a wheeled cart. At the base of the Acropolis the giant pep-

los was then taken down from the ship and carried up to be hung in a temple as a backdrop until

replaced in the next Great Panathenaia. In the time of Pausanias at least, the ship was parked

nearby until the next festival, on view for tourists.

The frieze measures 160m in total length, ca. 1m in height. It shows only portions of the pro-

cession; the ship, for example, is lacking. The scenes are clear enough, even if the exact under-

standing of who is doing what, and when, has been much debated. Horses and riders, all young

men, gather on the west side, then advance, picking up speed, along both long sides, the north

and the south (Figure 16.6). At the east end of the long sides, other participants in the procession

appear, men carrying hydriae, or water jars; officials; women; and sheep and cows for sacrifice.

On the east side, in the presence of seated gods the peplos is displayed, a folded cloth (although

perhaps originally painted with gods battling giants, the subject always woven into the peplos).

This frieze would have been difficult to see, placed high up in the shadows of the narrow

colonnade. Nevertheless the sculptors took no short cuts. Some aids were granted the viewer:

the frieze was thicker at the top than at the bottom, and the figures would have been painted

bright colors. Otherwise, the artists worked to please Athena. Details of bodies and clothes are

precisely carved. The composition is sophisticated and varied; participants in the procession are

shown in a great variety of poses, with overlapping in particular of horses and riders. How differ-

ent from the stately, repetitious procession of tribute bearers at Persian Persepolis!

The pediments

With this lively scene from the Panathenaia, the frieze offered worshippers a connection with

the actual religious life of the city. In the pediments, the sculptors returned to mythology, the

Figure 16.5 Parthenon, South Metope no. xxxi

ATHENS IN THE FIFTH CENTURY BC 259

favorite source of subject matter. Unlike the metopes, with their allegorical treatment of recent

Greek history, the pediments show episodes from the distant mythical past of Athens. In depict-

ing regional legend, they resemble the east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, with the

fateful chariot race about to begin. All pedimental figures were completed on the invisible back

side as well as the front, another testimony to the reverential attitude of the artists toward work

done for this temple.

Only a small number of the pedimental figures were decently preserved when Lord Elgin

stripped the Parthenon of sculpture. Because these pieces are so few, the original appearance of

the pediments eludes us. Pausanias noted only the basic subjects, not the complete cast of char-

acters or their arrangement in the triangular space. Furthermore, the explosion of 1687 seriously

damaged the sculpture. Drawings made earlier, in 1674, by French painter Jacques Carrey help,

but they are not as precise as we might wish; in any case by Carrey’s time some portions, notably

the center of the east side, had already disappeared.

In the important position over the main entrance to the temple, the east pediment depicted

the distinctive birth of Athena: she emerged fully armed from the head of her father, Zeus, when

he was knocked on the head by Hephaistos. Zeus and Athena must have been shown in the now

vanished center. The miraculous event, so important for the city of Athens, was witnessed by

divinities arrayed on either side of Zeus and Athena, standing, sitting, or even reclining to fit the

height of the pedimental space diminishing into the corners. These deities represented the other

cults of Athens welcoming Athena within their midst.

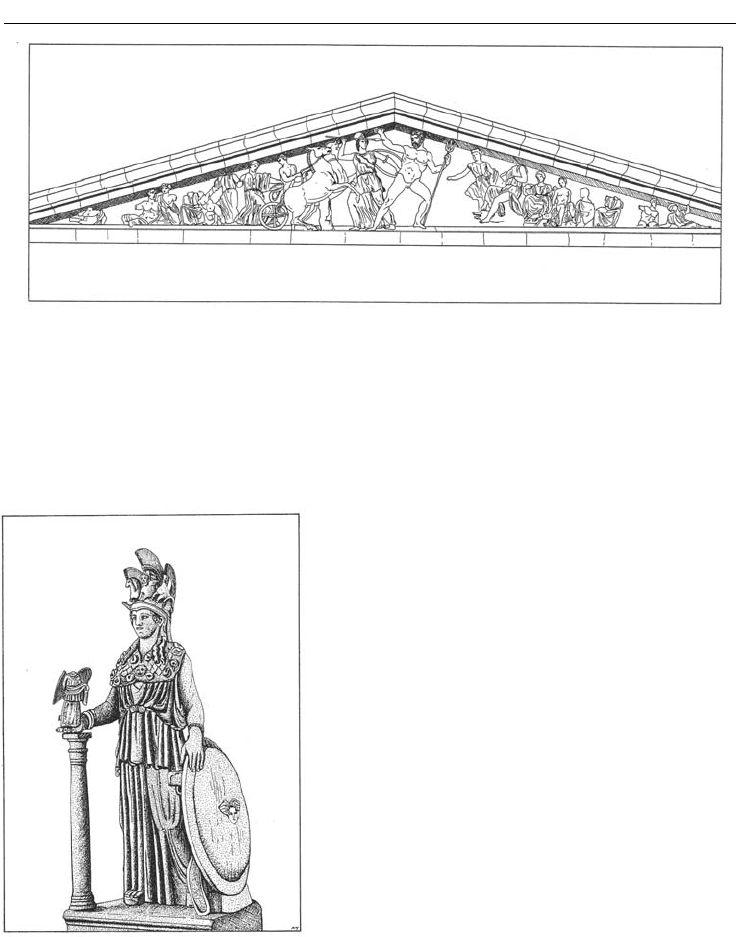

The west pediment showed Athena’s victory in her contest with Poseidon for the position

of patron deity of the city (Figure 16.7). A miracle was required of each. When Poseidon struck

the ground with his trident, water had bubbled forth – salt water, appropriate for the god of the

sea. Athena then created an olive tree on the barren Acropolis, a feat that was life-sustaining

for humans at least, in contrast with the salt water spring. The miraculous olive tree may have

occupied the center of the pediment, with an excited Athena and Poseidon stepping back on

either side, the event witnessed by gods, goddesses, horses and chariots, and perhaps families

prominent in the legendary origins of the city.

Figure 16.6 Parthenon, West Frieze, Slab II, nos. 2–3

260 GREEK CITIES

The cult statue

The final piece of sculptural adornment was the cult statue itself, a work of Pheidias. This colos-

sal chryselephantine statue of Athena disappeared in late antiquity, but the detailed descrip-

tion left by Pausanias, statuettes that roughly copy it

(Figure 16.8), and depictions on coins provide evi-

dence for a reconstruction. With its complex array

of victory imagery, the statue, as indeed the entire

temple, was a reminder that Athena led the Greeks to

triumph against the Persians. The goddess stood ca.

12m high. She wore a peplos and her armor: a breast-

plate and a triple-crested helmet, and with her left

hand she held a spear and shield. A snake lay curled by

her left foot, just inside the shield. In her outstretched

right palm, supported on a column, she held a statue

of Nike, winged victory, her offering to the city. The

colossal Athena was a vehicle for display of allegori-

cal myths appropriate for Greek victory: the Greeks

fought Amazons on the outside of the shield; gods

pitted against giants, possibly painted, on the inside;

and Lapiths vs. centaurs on the thick edge of her san-

dals. An unusual scene, in contrast, appeared on the

statue’s base: the birth of Pandora, attended by gods.

After Prometheus had stolen fire for humans against

the will of the gods, Zeus in anger had Pandora cre-

ated and sent to earth, carrying with her a box filled

with all possible miseries. The box once opened,

the evils escaped, becoming an ineradicable part of

human existence. Here in the Parthenon, the appearance of Pandora seems intended as a caution

to the Athenians in their hour of triumph.

Like the later Zeus of Olympia, the statue was made of a skin of ivory and costume of thin

sheets of gold fitted onto a wooden framework. The gold, weighing 44 talents (= approx.

1,120kg), belonged to the city, was inventoried every four years by the state treasury, and could

Figure 16.7 Parthenon, West Pediment (reconstruction), after the drawings of Carrey (1674) and

Quatremère de Quincy (1825)

Figure 16.8 The Varvakeion Athena, a

marble statuette; a Roman copy of

the Athena Parthenos. National

Archaeological Museum, Athens

ATHENS IN THE FIFTH CENTURY BC 261

be removed for safe-keeping. Pheidias was accused of stealing some of this precious material.

Whether true or simply slander, he left Athens for Olympia, where he made the statue of Zeus.

Where he ended his days is unknown. Whatever the truth of his complex life, his sculpture

– votives for the Acropolis, the complex program conceived for the Parthenon, and the cult

statue for Olympia – has stood as a benchmark for Classical Greek art in its grandeur, nobility of

expression, and precision of execution.

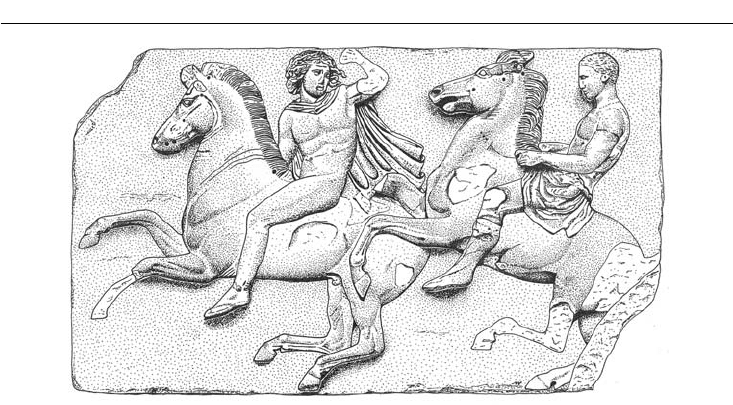

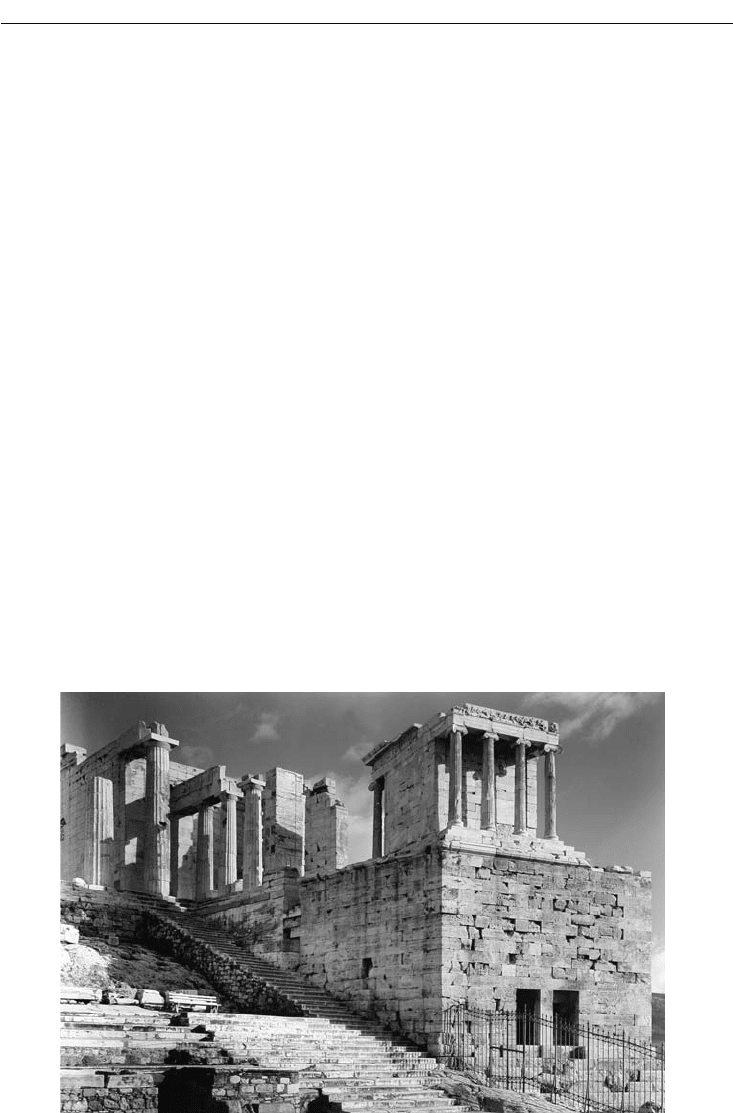

The Propylaia

When the construction of the Parthenon was coming to an end, attention turned to the entrance

to the Acropolis. Here, on the west end of the rock, a new monumental gateway was built, the

Propylaia (Figure 16.9). Mnesikles, the architect, worked on the building from 437 to 432 BC

on the eve of the Peloponnesian War, at which point work stopped even though the finishing

touches had not yet been applied.

In ground plan, the Propylaia consists of a main hall on the west–east axis, which gives access

to the Acropolis, and flanking chambers on the north-west and south-west. The main hall is built

on two main levels, reflected in the original two-part roofing, with the east section somewhat

higher than the west. A cross-wall marks the point where the east section begins; it is pierced by

five passageways, with the central one, a ramp, being the widest. On the west and east exteriors,

the Propylaia displays the Doric order, with a wider spacing for the central ramp, but three pairs

of Ionic columns, tall and slender, line the west portion of the central passageway. One can still

see some of the ceiling coffers, the marble blocks carved with squares, one inside the other, that

were placed over the cross-beams as ceiling decoration.

The side chambers of the Propylaia differ, the north from the south, creating an asymmetrical

plan. A small room on the north-west, provided with benches and wall paintings, served as a rest

Figure 16.9 Propylaia, south-west wing, as restored, and Temple of Athena Nike with bastion, from

north-west