Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

272 GREEK CITIES

Thymele), and the abaton. The buildings have been largely destroyed, leaving only foundations.

With one exception, they do not impart as lively a picture of the activities that went on here as

do the inscriptions and literary texts. The exception is the tholos, with its mysterious, intriguing

foundations: six concentric rings of tufa (a volcanic stone) with doors in the inner rings, creat-

ing a maze in the inner three passages. Cuttings in the stone suggest wooden steps led from the

main floor down into this crypt. The purpose of this unique maze, indeed of the entire building,

remains uncertain. The tholos was certainly prestigious: surviving architectural pieces show a

high quality of work. According to the building accounts, inscribed on stone, construction lasted

over thirty years, payment being dependent on a steady trickle of donations. But faith was kept,

the building completed. One popular view interprets the crypt as a home of the god’s sacred

snakes, but a leading specialist on Epidauros, R. A. Tomlinson, prefers to identify the tholos

as a funerary monument for Asklepios as a mortal (in contrast to the temple, which honored

Asklepios as a god).

The theater

The best-preserved structure at Epidauros lies not inside the sanctuary, but nearby: the theater,

designed by Polykleitos (not to be confused with the fifth century BC sculptor of the same name)

and erected in the later fourth century BC (Figures 17.3 and 17.4). Theatrical performances were

religious rituals for the Greeks, so it is not surprising that this sacred center should have one. The

theater accommodated ca. 14,000 people, a testimony to the broad regional appeal of these festi-

vals. The curved seating, or cavea, was built against a hillside and occupied more than a half circle.

Figure 17.3 Plan, Theater, Epidauros

THE LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD 273

Stone seating gave the form regularity, the site permanence. Several passages allowed spectators

access to seats. The horizontal diazoma divides the cavea into upper and lower halves, with the

upper half steeper than the lower. Vertical stairways are found throughout, with twice as many in

the upper half. At the base of the cavea lies the circular orchestra; here the chorus performed, chant-

ing and dancing. Beyond lay the stage building, or skene, a platform for the solo actors (the proskene)

with a backdrop. In the Greek theater, the skene is not attached to the cavea, but is separated by

passageways on either side, parodoi, marked here at Epidauros by post and lintel doorframes. The

Romans would later attach the skene to the cavea, now reduced to a half circle, thereby creating a

unified architectural structure. Through time, with solo actors dominant in Greek and Roman the-

ater, the stage building with its vertical backdrop became increasingly elaborate. Because the skene

at Epidauros has survived only in foundations, the stage building is better appreciated elsewhere,

such as at Priene (for the Classical–Hellenistic type) and Aspendos (the Roman type).

PRIENE: A SMALL GREEK CITY

The city of Priene, located in south-west Turkey near the Aegean sea, is justly famous as an unusu-

ally well-preserved example of a Late Classical–Hellenistic city plan. It was never an important

town, however, and its population was small, perhaps only 4,000. Despite its size, the city man-

aged to equip itself with the public buildings characteristic of Greek city-states, including those

necessary for democratic government. In the late Hellenistic period, its prosperity faded and, to

the great fortune of archaeologists, the buildings were never replaced. As a result of this modest

destiny, Priene shows us an ancient Greek city in a comprehensive way that richer, much rebuilt

centers such as Athens cannot (Figure 17.5).

Figure 17.4 Theater, Epidauros. The stage building is modern

274 GREEK CITIES

The building history of Priene is striking, for the city occupied two different sites in the Mean-

der River valley. Although the existence of the early town, founded by Greek emigrants in the

Iron Age, is attested from literary sources and coins, the exact location has never been identified;

it must lie buried deep in accumulated silt. Indeed, as the river carried eroded earth down from

the hills, the shoreline was continually shifting westward, and the town found itself more and

more inland. In the middle of the fourth century BC the citizens of Priene decided to move closer

to the seacoast. Magnificently situated on a bluff overlooking the Meander River and, in the dis-

tance, the Aegean Sea, with a protecting mountain looming behind, this second Priene makes a

dramatic impression on visitors.

Figure 17.5 City plan, Priene

THE LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD 275

With the river actively continuing to bear silt, even in their second location the people of

Priene found themselves farther and farther from the sea, their economic prospects fading. A

widespread destruction deposit indicates a damaging blow in the late second to early first centu-

ries BC, possibly connected with the violent revolt of Mithridates VI, king of Pontus, against the

Romans in 88–85 BC. Habitation dwindled, and the town would never recover.

The plan of the city refounded in the fourth century BC can be understood clearly both in

overall scope and in details, thanks to excavations conducted by the German Archaeological

Institute notably in 1895–98. The fortifications mark the perimeter, walls of neatly cut ashlar

blocks that can still be followed for most of their length, tracing the curve of the bluff on which

the city is located. In addition, the defense system incorporated the mountain behind. The layout

of the town within the walls features streets at right angles in accordance with the principles of

planning associated in the Greek world, at least, with the fifth century BC urbanist, Hippodamus

of Miletus. Hippodamus left no writings; his work was commented on by various ancient writers,

notably Aristotle in his book Politics. Hippodamus was described as having “invented the division

of cities” and “cut up Peiraeus,” the port of Athens. These divisions were not only physical but

also social. A city of ten thousand, Hippodamus proposed, should be divided into three classes

(artisans, farmers, and warriors), its land into three parts (sacred, public – to provide food for the

warriors – and private). The “cutting up” of Peiraeus appears to refer to physical division, with

the finds of inscribed boundary stones from the fifth century BC indicating different planned

districts. But Peiraeus has a varied topography; the grid plan was applied only to its flat central

section, it seems, not to its hilly areas.

At Periene, as in Peiraeus and most other planned Greek cities, the Hippodamian rules are

not scrupulously followed. The agora, for example, does not straddle precisely the axis of the

main east–west street, and the stadium, carved into a restricted space on the lower hillside,

could only fit on the diagonal. In addition, the city proper lies on sloping ground; this too neces-

sitated adjustments. The east–west streets, more-or-less level, permitted wheeled vehicles,

but the north–south paths were too steep; steps were often added. As in many Aegean

villages before the advent of the motor car, foot traffic, animal and human, must have

predominated.

The open-air rectangle of the agora or city center is neatly defined by stoas on all four sides.

The precise geometric form of this planned public space, characteristic of newly founded cities

in Greco-Roman antiquity, contrasts with the irregular, ever-changing urban centers that devel-

oped gradually over the centuries, such as the Athenian Agora. The stoas themselves are simple

structures, but inside their sheltered colonnades a great variety of activities took place: legal

affairs, government offices, shops, perhaps shrines, and simply meeting and chatting; and they

always offered good shelter during a cold winter rain or on a hot summer day.

Stoas also served as architectural screens hiding diverse buildings behind; with their uniform

line of columns, they preserved the harmonious appearance of the public square. Here at Priene,

the eastern stoa masks a small temple, probably dedicated to Zeus; and behind the western stoa

lay a meat and fish market. Nestled against the hill behind the impressive north or Sacred stoa

stands one of Priene’s best preserved buildings, the Bouleuterion or Council Chamber (Figures

17.6 and 17.7). The bouleuterion looks like a small indoor theater. Almost square in outline, it

has steeply rising rows of stone benches on three sides, seating for an estimated 640 people, and

on the fourth side, between two doorways, a recess lined with stone benches for the presiding

officials. In the center of the room stood a small altar used for the sacrifices performed at the

beginning of each meeting. The wooden roof has not survived. Because of the width of the

building, 14.3m, the roof needed the additional support of pillars set inside the room.

276 GREEK CITIES

Figure 17.7 Bouleuterion, interior (reconstruction), Priene

Figure 17.6 Bouleuterion, Priene

THE LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD 277

Below the agora on the side opposite the bouleuterion lie the gymnasium and the stadium,

cut into the south slope of the bluff in the second century BC. Because of the steep terrain, the

stadium has a truncated plan, with seating on the north (city) side only. Fragments of the stone

starting line, an addition of the Roman period, still exist, with cuttings that once held an elaborate

starting mechanism, a rig of posts and cords that assured a simultaneous start for all eight run-

ners. The gymnasium is noteworthy for unusual features preserved in the rooms on the north

side of the court. The central hall served as a schoolroom for boys, many of whom carved their

names on the walls. Over 700 names can still be read; for example, “The place of Epikouros son

of Pausanias.” Next to the lecture hall was a washroom. Stone basins placed on either side of

the doorway served for rinsing feet, a row of basins along the rear walls of the room for hands

and faces.

Up the hill from the bouleuterion one reaches the theater. Built early in the city’s existence, it

preserves its Hellenistic Greek character despite some modifications in the Roman period (Fig-

ure 17.8). In Greek fashion as seen at Epidauros, the cavea is larger than a semicircle, although

the rear section is truncated at the sides, and is separated from the skene by parodoi. But some

features in this theater differ from Epidauros. Five stone armchairs, perhaps reserved for priests,

line the orchestra. The stage building consists of two parts, a high raised platform in front, the

proskene (proscenium), and an even taller portion behind. The façade below the proskene is

decorated with twelve columns that mark off a series of doors and panels, an effective backdrop

for Classical plays performed in the orchestra by the chorus and solo actors. In the post-Classical

theatrical tradition, the chorus lost much of its importance. The prominence of the solo actors

was emphasized by placing them on top, not in front, of the proskene. For all spectators except

the dignitaries in the front row armchairs, the view would have been immeasurably improved.

Figure 17.8 Theater (reconstruction), Priene

278 GREEK CITIES

To the west of the theater lie the remains of the Temple of Athena, the most important shrine

of the city. Its terrace above the north-west corner of the agora dominates Priene, but only the

foundations and five re-erected columns survive to indicate the temple’s original dimensions. The

temple is Ionic, not surprising considering that the architect, Pytheos, denounced the Doric order

with its intractable corner triglyph problem as incurably defective. The ground plan is standard,

provided with the standard pronaos, cella, and opisthodomos; in contrast, the surrounding colon-

nade differs from the expected, consisting of only eleven columns on each of the long sides instead

of the normal thirteen. The proportions of the temple were much admired, and indeed Pytheos

wrote a book about them (which has not survived). The temple is also of note for its distinguished

patron. Alexander the Great, when he passed through in 334 BC, offered to finance the construc-

tion in return for the privilege of making the dedication. The Prienians gratefully accepted.

Below the temple, the main street continues westward from the agora to the main residential

area of the town. The paved street, which slopes gently downward, has a good-sized drain run-

ning down its center. Off it on either side lie the foundations of numerous houses. These discov-

eries, together with the Athenian houses (above, Chapter 16) and the roughly contemporaneous

examples from Olynthos and Delos, give us a good picture of the home life of the solid citizen

in ancient Greece.

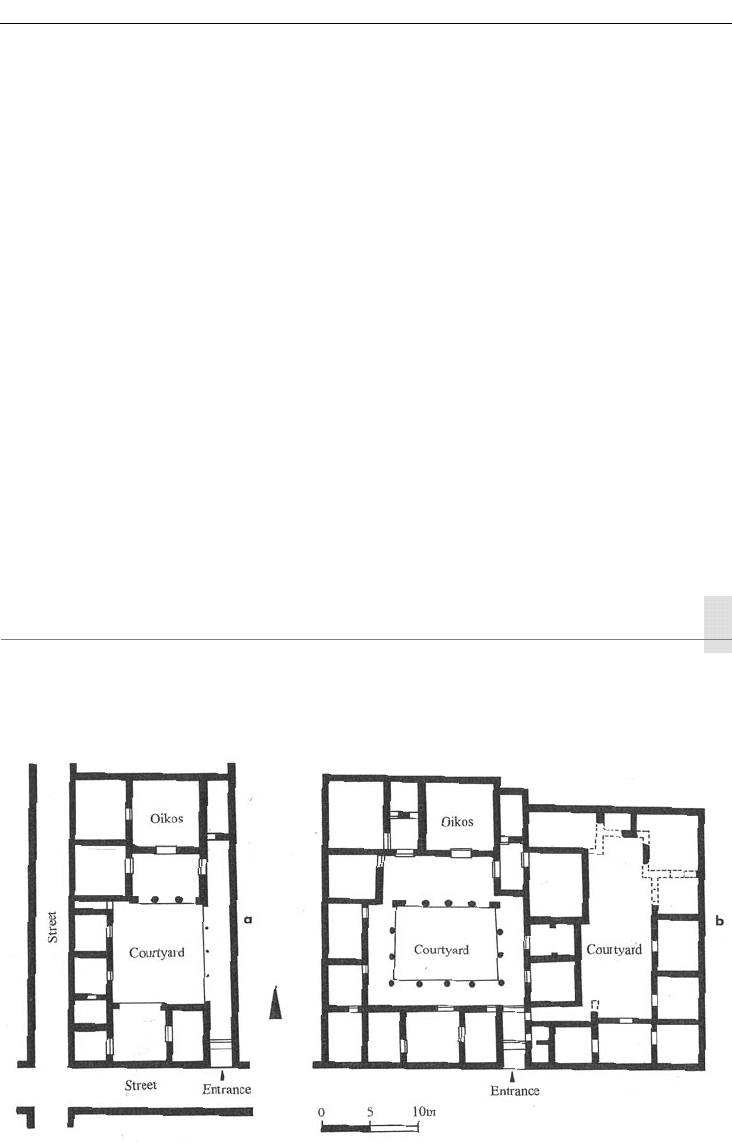

As in other Greek cities, at Priene the houses consisted of a central courtyard lined by colon-

naded porches and rooms behind (Figures 17.9 and 17.10). But here the rooms at the rear end of

the court are emphasized: the roof line is higher, and consequently the columns of the porch are

taller, more prominent. This architectural unit of a porch plus main room recalls the megaron of

Bronze Age Trojan and Mycenaean architecture.

OLYNTHOS: HOUSES

Additional information about Greek houses has come from Olynthos in northern Greece; with

over 100 houses excavated, this constitutes the biggest sample yet known. Olynthos flourished

Figure 17.9 Plans, House no. 33, Priene: (a) Phase 1-West; and (b) Phase 2

THE LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD 279

from 432 BC until its destruction by Philip II in 348 BC; final abandonment occurred in 316 BC.

Excavations were conducted in four seasons from 1928 to 1938 by David Robinson of Johns

Hopkins University. With building foundations nicely preserved, the city layout emerges clearly,

as do the plans of individual homes. The well-exposed urban plan makes us think of Priene, and

indeed the population of the two towns was roughly the same. In contrast with Priene, however,

religious buildings are lacking and public buildings are few; no doubt the excavators did not

explore the appropriate places.

Certain aspects of the housing recall Priene. Blocks of adjacent houses sharing walls are neatly

arranged along straight streets, laid out in parallel lines. Houses are similarly hidden from the

street by an enclosure wall, and inside, the courtyard is the focus. But there are differences. The

normal shape of the Olynthian house is square, not rectangular (Figure 17.11). Moreover, behind

the court lies a portico, the pastas, an intermediate space between the court and the small rooms

behind. Also distinctive is the andron, or men’s dining room. This, the most elaborate room of

the house, frequently decorated with a floor mosaic, was set apart from the other rooms, with

entrance often through a smaller anteroom. Here the man of the household received his guests;

together they ate while reclining on benches set alongside the walls. Ancient Greek society per-

mitted considerable freedom for men, but respectable women were restricted to the house and

family, for whose maintenance and well-being they were responsible. Wives would not join these

dinner parties. The only women present might be musicians and other entertainers.

Figure 17.10 House no. 33 West (reconstruction), Priene

280 GREEK CITIES

As for the food, ancient Greek meals might well strike us as dull, simple, and lacking in variety.

For one thing, tomatoes, peppers, and potatoes, mainstays of modern Mediterranean cooking,

had not been introduced. New World plants, they were brought to Europe by Spanish explorers

of the sixteenth century. Meals included bread, eggs, cheese, soup, cooked cereals, fish (espe-

cially dried and salted fish) but rarely meat; garlic, onions, beans and lentils, nuts and olives; olive

oil (also used for frying); for dessert, figs and other fruits,

and cakes, sweetened with honey (neither sugar cane nor

the sugar beet were available). Wine, a staple drink, was

routinely diluted with water, five parts water to two parts

wine, with the water politely poured first into the krater,

or mixing bowl; sometimes other, to us incredible, sub-

stances were added, such as sea water and even chalk or

powdered marble. As today, certain places were famous

for their specialties. The wine of the east Aegean was

especially praised, from Rhodes, Knidos, Samos, Chios,

and Lesbos. These islands and cities, and Thasos in the

north Aegean, exported wine in large plain clay trans-

port amphoras of distinctive shape (Figure 17.12). Often

their handles were stamped while the clay was still wet.

These stamps, which are widely found in east Mediter-

ranean archaeological sites, give valuable information

about manufacturers, public officials, and dates.

Floor mosaics

Floor mosaics were a characteristic feature of later Greek and then Roman cities, both in private

houses and in public buildings. The floor mosaics from Olynthos are among the earliest from

the Greek world. Floor mosaics, designs created by, first, colored pebbles and, later, cut pieces

of stone set into cement, originated in the late fifth century

BC at Olynthos and Corinth, becom-

ing popular in the fourth century BC. Earlier mosaics have been discovered at such Iron Age

towns as Ziyaret Tepe (south-east Turkey) and Gordion, but these Neo-Assyrian and Phrygian

Figure 17.12 Transport amphoras from

the Athenian Agora: (a) Chian, fourth

century BC; and (b) Rhodian, third

century BC

Figure 17.11 House plans, Olynthos

THE LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD 281

examples did not have direct descendants. Why the fashion arose in Greece in the later Classical

period is not clear.

Mosaics fall into two groups according to the type of material used, pebbles and tesserae. For

pebble mosaics, the earlier of the two types, naturally shaped and colored pebbles were used to

make the picture, sometimes with baked clay or lead strips added as outlines. By careful juxtapo-

sition of the colors, images could be shaded. In this the craftsmen making mosaics were follow-

ing the artistic conventions already developed for prestigious mural painting in which volume

and depth of space were indicated by shading, that is, by contrasts of light and dark achieved

by the manipulation of different tones of color. Although the pebble mosaics of Olynthos are

important, the finest known series comes from Pella, the capital of ancient Macedonia.

During the early Hellenistic period, pebbles were replaced by tesserae, cut pieces of stone,

glass, or terracotta of various colors. By the second century BC, craftsmen could even cut pieces

1mm square; the mosaic technique that utilized such tiny pieces was called opus vermiculatum. With

tesserae, shading could be controlled with greater precision. Tessellated mosaics were costly,

however, because the laying of a mosaic floor demanded considerable time. Nevertheless, mosa-

ics continued in popularity as floor decorations for the houses of the wealthy and certain public

spaces (such as walkways under porticoes) through the Roman Empire – and in late antique and

Byzantine times, notably in churches, for wall and ceiling decoration, and, in some regions such

as Jordan, for floors.

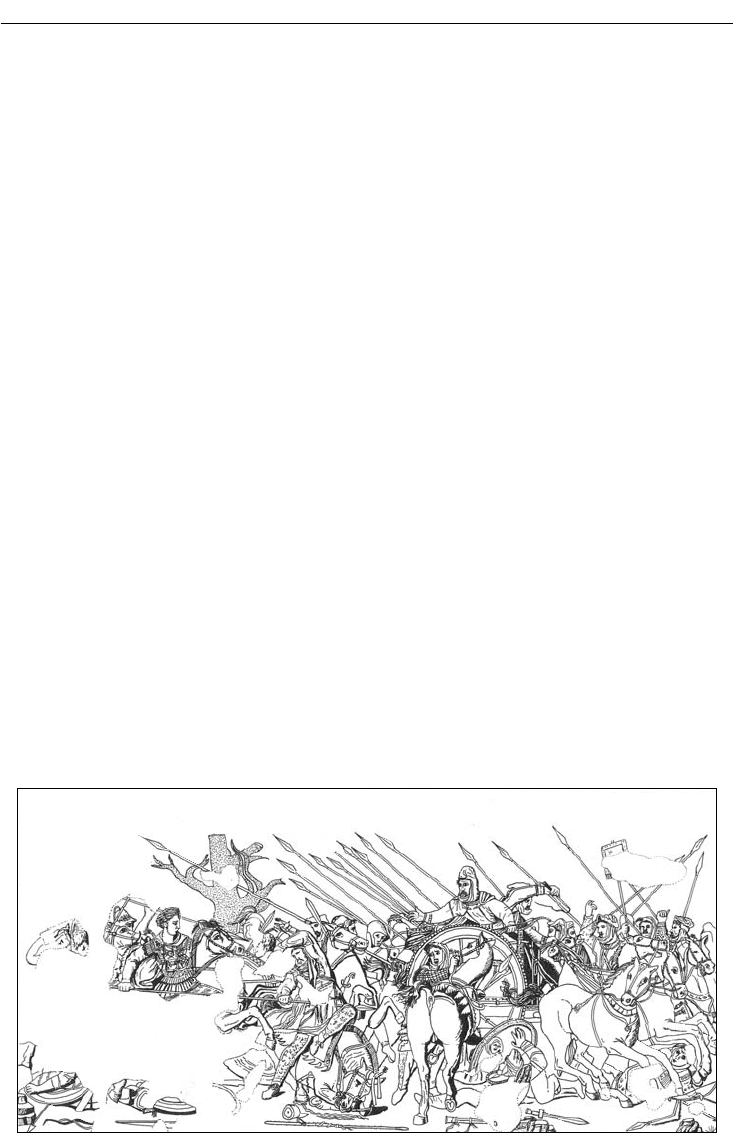

The Alexander Mosaic from Pompeii is the best-known example of an early tessellated mosaic

(Figure 17.13). Found in the exedra, a reception room of the House of the Faun, this large floor,

5.1m × 2.7m (without its perspectival border), made ca. 100 BC, is believed to copy a lost wall

painting of the late fourth century BC. In the panel, Alexander the Great faces off against Darius

III, the Persian king, in the crucial Battle of Issos. In the lower half of the scene, soldiers, weap-

ons, and horses collide and intertwine. The upper half is spare, with a dead tree indicating the

landscape and upraised spears punctuating the otherwise empty space. In this void Darius, in the

higher, focal point of the picture, makes eye contact with Alexander on our left; the confronta-

tion of the two men rising above the mayhem distills the clash of powerful armies. Observed

in a photograph or on the wall, as the mosaic is now displayed in the Archaeological Museum

Figure 17.13 The Alexander Mosaic, House of the Faun, Pompeii. Archaeological Museum, Naples