Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

282 GREEK CITIES

in Naples, the scene can be appreciated in its entirety.

The ancient viewer, in contrast, standing on the floor,

had to be content with a close look at a few details or a

distorted raking view.

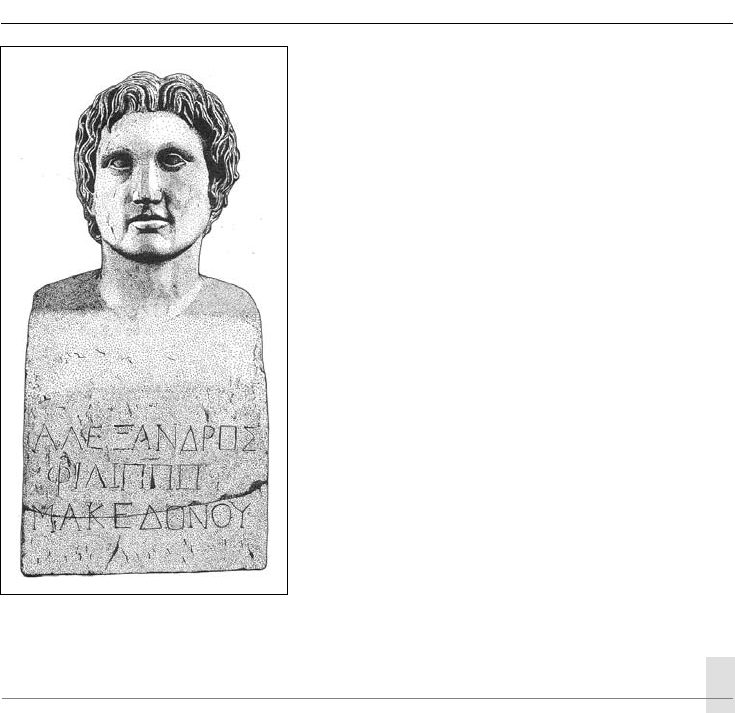

Many other images of Alexander the Great have sur-

vived, made both during his lifetime and after, when a

recollection of the great conqueror could serve as an

inspiration. Illustrated here is a portrait known as the

Azara Herm, named after the first owner in modern

times (Figure 17.14). This Roman Imperial portrait,

made in the first or second century AD, is generally con-

sidered a copy of an original by the famous Greek sculp-

tor Lysippos, of ca. 330 BC. The inscription, in Greek,

reads “Alexander, son of Philip the Macedonian.” Such

portraits, seen in sculpture and on coins, may not be

strictly faithful likenesses, but thanks to certain conven-

tions – always a clean-shaven young man with distinc-

tive wind-swept hair – his was an easily recognizable

image. For imparting the message, recognition was all

important.

VERGINA AND HALIKARNASSOS: ROYAL BURIALS

With Alexander the Great, his father, Philip II, and Alexander’s Macedonian generals who divided

up their empire, kingship becomes an important element in the Greek world – a development

of interest for us, because rulers, as we have seen so often, make significant contributions to the

artistic and architectural environments of cities. Late Classical and Hellenistic monarchs are no

exception. Priene, in contrast, has little to contribute here, being democratically governed, and

without spectacular conquests or other achievements that merited expensive public commemo-

rative monuments. (Priene did, however, receive gifts from outsiders; as noted earlier, Alexander

the Great financed the completion of the Temple of Athena.) We shall now turn elsewhere, to

tombs at Vergina and Halikarnassos – indeed both outside the heartland of Greek culture – to

find striking examples of royal initiatives in material culture in the fourth century BC.

The importance of burials as expressions of wealth and power has been another theme char-

acterizing many cultures of the Ancient Near East, Egypt, and the Bronze Age Aegean. Greece

has differed from this pattern. After the early Iron Age with the spectacular burial at Lefkandi

and the great funerary vases at the Dipylon cemetery in Athens, burials become relatively mod-

est. When pressure did increase for public display, reaction set in: at Athens in 317 BC anti-luxury

laws were passed in order to curb lavish spending on burial monuments. Excavations at Priene,

so informative about other aspects of its urban plan, report little about the disposal of the dead,

which took place outside the city walls. With the renaissance of kingship, the Greek world once

again saw important attention devoted to burials.

Figure 17.14 Portrait of Alexander the Great (the Azara

Herm). Roman Imperial copy of an original by Lysippos.

Louvre Museum, Paris

THE LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD 283

Vergina

Among the many discoveries made by Manolis Andronikos of the University of Thessalon-

iki at Vergina, ancient Aegai, an early capital of Macedonia, the most spectacular were three

royal tombs dated to 350–300

BC. Two of them, Tombs II and III, were found intact. Androni-

kos assigned Tomb II to Philip II. Evidence for this attribution is strong. Greaves (metal shin

guards) of different lengths recall Philip’s lameness. A tiny ivory portrait shows a man with only

one good eye, which was the case for Philip; this distinctive characteristic is, moreover, a feature

of the skull found in the tomb, as a forensic reconstruction of the skull has revealed. Tomb III

may well belong to Alexander IV, the posthumous son of Alexander the Great, but the occupant

of the other tomb is unknown.

The tombs were built of masonry and then hidden, buried beneath a broad low tumulus. In

plan they are simple: Tomb I has one small room only, without a doorway; Tombs II and III

consist of an antechamber and main room behind, both rooms barrel vaulted. Tomb II, the larg-

est of these tombs, measures 4.46m wide by 9.50m deep. Its façade resembles the short end of

a Doric order temple, with a two half-columns, an architrave, a triglyph and metope frieze, and

above, a horizontal frieze panel painted with a hunting scene.

Tomb I, discovered robbed, was nonetheless decorated with a wall painting quickly hailed

as one of the most important finds of Greek art in modern times. On the north wall in a space

measuring 3.5m × 1.0m, Hades has seized Persephone and is carrying her off in his chariot.

The colors are white, yellow, and purple. The drama of the composition, the quick, impres-

sionistic brushwork, and the use of light and shadow to create volume make for a picture

much more nuanced and expressive than the relatively stiff drawings on Attic black and red-

figure pottery. This wall painting fulfills all expectations we have about the quality of monu-

mental Greek painting, an art highly esteemed by the ancients, but which has almost entirely

disappeared.

Halikarnassos

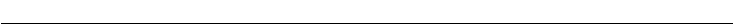

At the time of Priene’s refoundation ca. 350 BC, not far to the south, in the city of Halikarnas-

sos, the most celebrated of all funerary monuments in the Greek world was being erected: the

Mausoleum. In contrast with the tombs at Vergina, the Mausoleum was visible, an expensive

public display of royal prestige. Halikarnassos (modern Bodrum) was a small port founded by

Dorian Greeks during the Iron Age migrations to the east Aegean; later it joined the Ionian

confederation. Its most famous son was the historian Herodotus. During the fourth century

BC,

this region, known as Caria, was administered for the Persians by the Hecatomnids, a non-Greek

Carian family based in inland Mylasa (modern Milas). Soon after he inherited the throne in 377

BC, Mausolus moved his capital from Mylasa to the seacoast, to Halikarnassos, embellishing it

with new fortifications, a protected harbor, temples, and a palace. Upon his death, Artemisia, his

widow and sister (a royal marriage in the Egyptian tradition), oversaw the completion of his mag-

nificent tomb designed by Pytheos of Priene and Satyros of Paros and decorated in the Greek

style. So splendid were its design, materials, and decoration that its name, Mausoleum, entered

common parlance to denote any elaborate above ground funerary monument.

The Mausoleum survived into the Middle Ages, when its final demolition took place at the

hands of the Knights of St. John, crusaders who used its cut stone in the building of their castle

in the harbor. But its appearance can be reconstructed from descriptions of Pliny the Elder,

the first century

AD encyclopedist, and Vitruvius, and from British (1857 and 1865) and Danish

(1966–77) archaeological investigations at the site (Figure 17.15).

284 GREEK CITIES

The Mausoleum stood on the slope a short way above the harbor, in the north-east part of a

large terrace, ca. 105m × 242m. Measuring ca. 30m × 36m × 42m, the building rose in four stages

above the burial chamber. The subterranean tomb chamber was approached by a broad descend-

ing staircase, at the bottom of which were found horses, killed as a sacrifice. A massive stone plug

blocked further entrance, but thieves broke in nonetheless, perhaps in the Middle Ages.

Of the building proper, the lowest stage was a tall base rising in three tiers. The second stage

consisted of a temple-like colonnade of thirty-six Ionic columns surrounding a “cella.” Above

this, the third stage, a roof of twenty-four steps, rises like a pyramid to a small platform on which

stood the fourth and final element, a statue of Mausolus and Artemisia in a quadriga, a chariot

drawn by four horses.

The structure was lavishly decorated with sculpture. Pliny reports that the four best-known

sculptors of Greece were commissioned to do a side each – Scopas (east), Bryaxis (north), Timo-

theus (south), and Leochares (west) – but attempts to distinguish different hands in the best

preserved part of the sculpture, the reliefs from the top of the base that show the battle between

Greeks and Amazons, have been futile. The other sculpture is highly fragmentary, and its place-

ment on the monument remains hypothetical.

The Mausoleum illustrates the cultural mix that characterized the city of Halikarnassos.

Erected by a non-Greek ruling family in the sway of Greek culture, the monument combines

both native Anatolian and Greek elements. Although architectural details and sculptural style

are Greek, the concept of the monument – a temple-like building on a high base – is very much

at home in non-Greek West Anatolia. Distinguished predecessors include the Nereid Monu-

ment from Xanthos, ca. 380

BC, and, for the roof, the mid-sixth-century BC Pyramid Tomb at

Sardis. Much of the pictorial imagery comes from the standard tradition of Greek architectural

Figure 17.15 Mausoleum (reconstruction), Halikarnassos

THE LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD 285

sculpture, and does not follow the lead of the Nereid Monument with its scenes of historical

narration. Since this iconography in part recalled the victorious struggle of the Greeks against

the Persians, we may be surprised that it was reproduced here by non-Greek rulers nominally

subject to the Persian king. The allure and prestige of Greek art must have been so consider-

able as to outweigh the political references. Or, quite simply, the allegories embedded in the

sculpture may have been invisible for Mausolus, Artemisia, and their Carian subjects.

CHAPTER 18

Hellenistic cities

The nature of Greek civilization was considerably changed by the conquests of Alexander the

Great. With the spread of Greek rule throughout western Asia and Egypt, the Greeks con-

fronted and intermingled with neighboring cultures in a way never before imagined. This chapter

explores several themes that dominate the Hellenistic period, with impact on the nature of cities:

the continuing development of Greek art and architectural forms and styles; the effects of king-

ship on the urban experience; the intersection of politics and commerce; the Greek confronta-

tion with non-Greek cultures; the city as multi-cultural commercial center; and the influence of

geography. Examples that illustrate these themes will be one rural temple, the Temple of Apollo

at Didyma, and four cities, Pergamon, Alexandria, Delos, and Sinope.

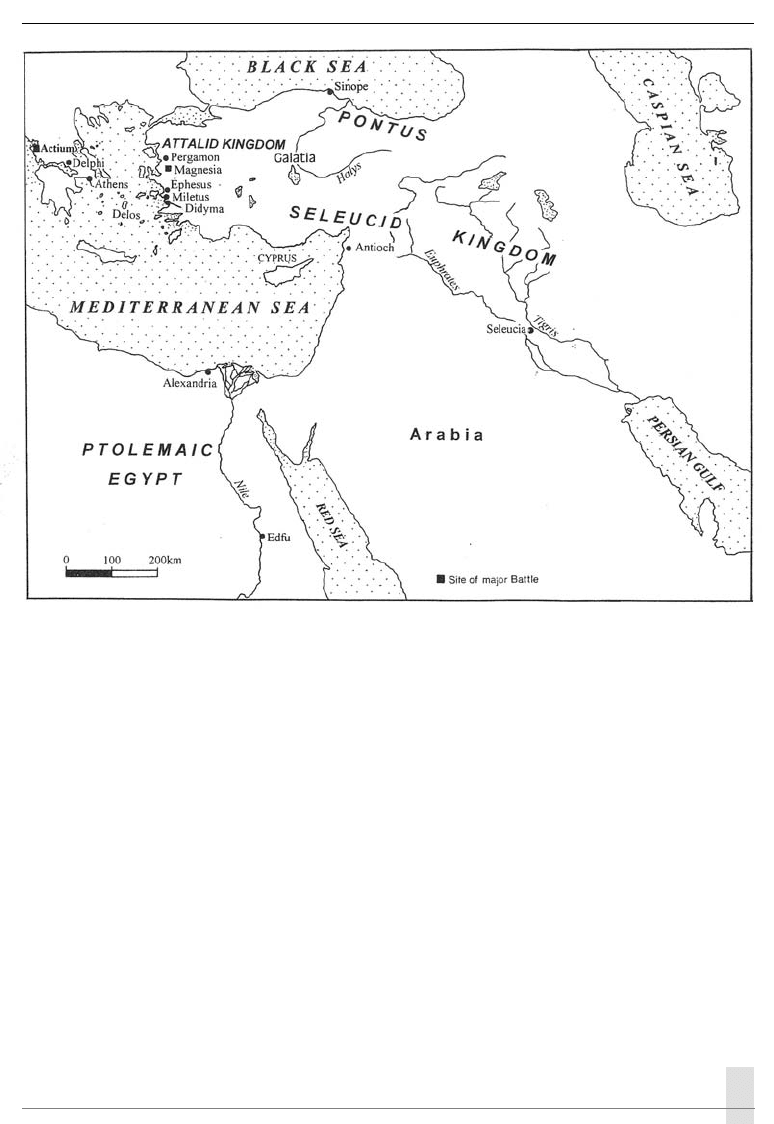

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

The conquests of Alexander the Great placed the Near East and Egypt in the hands of the

Greeks. After Alexander’s untimely death, a power struggle was inevitable: such tremendous

spoils would not go uncontested. Alexander’s young widow and son were no match for his bat-

tle-hardened Macedonian generals and soon disappeared. The generals divided the vast territory

among themselves, and in the Macedonian pattern, established new states which they and their

descendants would rule as kings during the following three centuries (Figure 18.1). Prominent

among them were Ptolemy, who took Egypt, establishing his capital at the newly founded Alex-

andria on the Mediterranean coast; Seleukos, ruling the Levant, Syria, and south-east Anatolia,

with capitals at Seleucia (Seleukeia) on the Tigris and later also at Antioch; and Lysimachos,

controlling Greece and western Asia Minor. In this age of kingdoms, the old Greek city-state

continued in name only, a quaint tradition without effective power. The democracy of Athens

was replaced by a governmental system indeed much older – and one that would lead smoothly

to the Roman and later medieval empires.

The term ‘Hellenistic’ refers to these centuries of Greek ascendancy in the eastern Mediterra-

nean and the Near East, even when (as in Mesopotamia and farther east) Macedonian kingdoms

soon gave way to non-Greek local rule. The period witnessed important advances in knowledge,

Death of Alexander the Great: 323 BC

Attalos III bequeathes Pergamon to Rome: 133

BC

Battle of Actium: 31 BC

HELLENISTIC CITIES 287

thanks to scientists, philosophers, and compilers, and to such institutions as the state-sponsored

libraries at Alexandria and Pergamon, in which learning was carefully organized and preserved.

In the arts, sculpture, painting, coinage, and mosaics elaborated the Greek tradition. But Greek

culture, although spread over the surface of this vast territory, filtered down to the non-Greek

subject peoples in varying degrees. In Asia Minor, Hellenization penetrated all levels of society,

but in Egypt and the Levant, the pre-Greek cultures held sway among the masses. The Greek

rulers themselves were not entirely immune to oriental cultures: the Egyptian concept of divine

kingship, for example, had an irresistible appeal.

The period also saw the increasing military and commercial involvement of the Romans in the

eastern Mediterranean, with accompanying territorial gains. Strictly a regional Italian power in

the fourth century BC, by the end of the Hellenistic period Rome controlled the entire Mediter-

ranean. The culmination in the east came with a naval victory at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. By

routing Cleopatra, queen of Egypt, and her ally Mark Antony, Octavian (later Augustus Caesar)

completed the Roman takeover of Greece, Asia Minor, Cyprus, the Levant, and Egypt.

DIDYMA: THE TEMPLE OF APOLLO

Greek temple architecture was notable for its conservatism, and this attitude continued in

the Hellenistic period. But the new era also valued the dramatic, the startling. No building

Figure 18.1 Major Hellenistic cities and kingdoms

288 GREEK CITIES

exemplifies better this typically Hellenistic combination of the traditional with the innova-

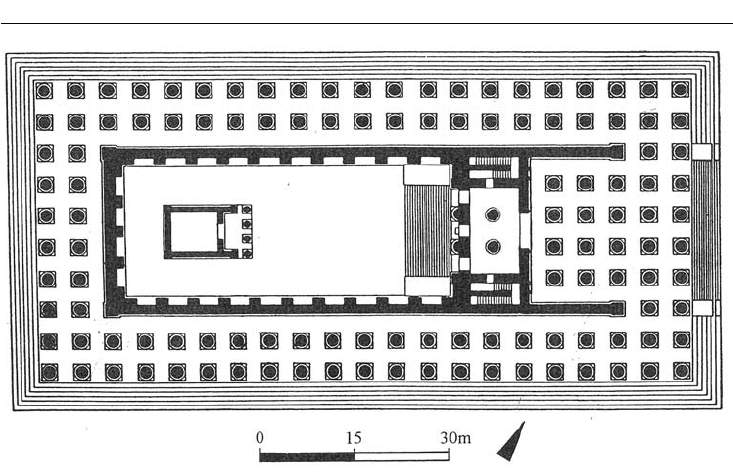

tive than the Temple of Apollo at Didyma (Figures 18.2). Moreover, ruined though it is, the

Temple of Apollo is the best surviving example of the colossal Ionic temples of East Greece.

From it we get some idea of the dimensions, the grandeur of the Temples of Hera at Samos,

of Artemis at Ephesus.

The temple is the principal building at Didyma, a religious center that contained, in addition

to the major sanctuary of Apollo, a smaller sanctuary to Artemis, and numerous public buildings

that catered to the welfare of pilgrims, such as stoas, shops, and baths. Immediately south of the

temple was a stadium, the site of athletic events held every four years during the major festival,

the Great Didymeia. The steps of the temple were used as seats; still visible are the many names

carved on them by spectators.

Didyma belonged to the city of Miletus. Located some 20km to the south, Didyma was con-

nected to Miletus by a processional route, a Sacred Way. Like Delphi, Didyma’s Apollo sanctuary

featured an oracle, but here a sacred spring served as the stimulus. The first major temple, built

in the Archaic period, was burned by the Persians in 494 BC when they sacked Miletus and sup-

pressed the Ionian revolt.

During the following 150 years the temple lay in ruins and oracle did not operate. When

Alexander the Great passed through, or so the story has it, the oracle and the sacred spring came

back to life, and soon a new temple was begun, the temple one visits today. Designed by the

architects Paionios of Ephesus and Daphnis of Miletus under the patronage of Seleukos, work

continued throughout Classical antiquity, a period of 600 years. The temple was never finished.

Traces of incomplete work can be seen on the exterior south walls of the temple: mason’s marks

(here, large letters), rough-picked surfaces, and bosses for securing lifting ropes – all of which

were normally removed in the final finishing of a wall. The oracle was permanently shut down

in the late fourth century

AD during the reign of Theodosius I, as were all pagan cults. The

Figure 18.2 Plan, Temple of Apollo, Didyma

HELLENISTIC CITIES 289

building itself suffered severely in subsequent earthquakes. The visible remains of the temple

were brought to the attention of western Europe by travelers beginning in the mid-eighteenth

century. Partial excavation followed during the nineteenth century, but the full clearing of the

temple was not completed until 1906–13, under the direction of Theodor Wiegand for the Royal

Prussian Museum in Berlin. After a long hiatus, the German Archaeological Institute resumed

exploration in 1962, with a focus on areas outside the temple.

Didyma is located on a flat plain not far from the sea. A sacred grove of trees surrounded the

temple on its west, north-west, and south-west side; and indeed the temple, with its many tall,

slender columns, must have given the impression of a majestic forest. On the large stylobate,

ca. 109m × 51m, a dipteral (double) colonnade around the cella was planned, ten columns wide

on the short ends, twenty-one on the long, for a total of 108 columns, plus an additional twelve

inside the pronaos. Three columns, nearly 2m in diameter, still stand to a height of 19.7m, giving

an idea of the imposing vertical dimension of the temple. The normal order of construction was

here reversed, with the colonnade coming after the cella. The variety of bases of the porch col-

umns and their decorations demonstrates that columns were set up and completed in different

periods, with many columns in fact never erected at all.

If the outside of the temple follows the traditions of Ionic architecture, the interior breaks

from the typical, offering one surprise after another. At the back of the pronaos comes the first

surprise: the expected entrance to the cella through the pronaos is blocked by an impossibly high

threshold without steps. Above is a room, the east chamber, entered from inside the temple (see

below); from here priests may have announced the oracular messages.

To proceed further into the temple, one must follow one of the two barrel-vaulted passages

that descend from the far corners of the pronaos. One emerges from the dark, cave-like tun-

nels into daylight and another surprise: the cella of this temple has been replaced by an unpaved

open-air court (ca. 53.5m × 21.5m) at a level much lower than that of the stylobate. At the far end

of this adyton, or sacred area, stood a mini Ionic temple, the naiskos, which sheltered the bronze

statue of the god, with either inside or just outside the sacred spring and laurel tree that inspired

the oracle. The north walls of the adyton are carved with architectural plans, blueprints of a sort,

to ensure uniformity in measurement and form: a network of finely incised lines, straight and

curved, up to 20m long, that show design details of the columns and other architectural elements

of the temple, their capitals and bases. These diagrams were incised ca. 250 BC when the adyton

walls were built, well after the deaths of the initial architects, Paionios and Daphnis. Similar draw-

ings have been found at Priene (Temple of Athena) and Sardis (Temple of Artemis) and in Egypt

and in certain Gothic churches in western Europe (Chartres and Reims, for example).

From the west side of the adyton a broad flight of steps leads up to the east chamber, the room

of the oracular messages. Staircases at each end give access to the roof. Some sculptural decora-

tion was provided for the temple, notably pilaster capitals and frieze for the upper edge of the

inner adyton walls, showing griffins. In Roman imperial times a frieze was carved for the exterior

entablature. The head of Medusa appeared here as she had for centuries, protecting the temple

against evil, but unlike the fierce gorgon of the early Archaic temple at Kerkyra, the Roman

Medusa at Didyma is fleshy, petulantly frowning, and thoroughly tamed.

PERGAMON: A CITY IN THE ATHENIAN TRADITION

If the Hellenistic sense of the dramatic emerges clearly in the Temple of Apollo at Didyma, its

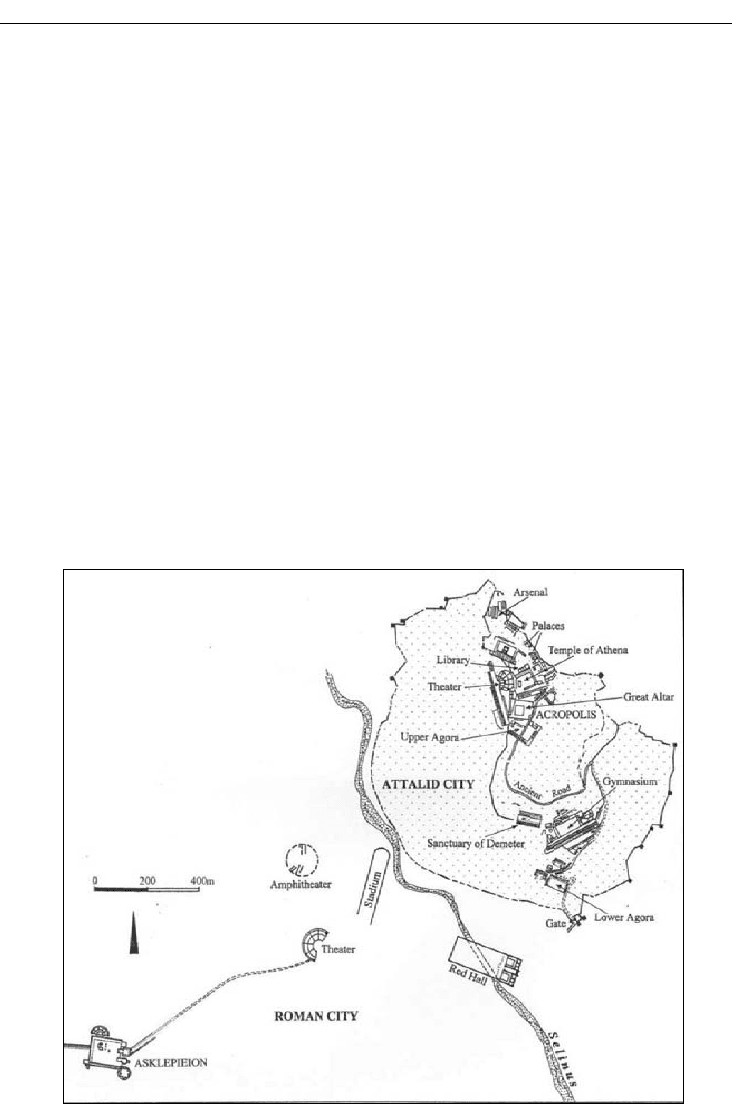

finest urban expression comes in the layout of Pergamon, one of the leading cities of western

290 GREEK CITIES

Asia Minor during Hellenistic and Roman times. The siting of the city was spectacular, on a hill-

top that rises at the back of a small coastal plain. The fortified summit, or acropolis, contained

the palace and certain key public and religious buildings. The city continued down the gentler

south slope (the other sides are steep), eventually spreading by Roman times onto the plain, now

occupied by the modern town, Bergama (Figure 18.3). In its very layout, with palaces and temples

raised high, Pergamon reminds us that this was the capital of a kingdom, not a democracy – in

striking contrast with Priene, where the agora and bouleuterion lie in the center of the city, with

the Temple of Athena benevolently looking down from one corner. The correspondence at Per-

gamon between the natural topography and hierarchical society cannot be said to characterize

Hellenistic cities – Alexandria, for example, lies on flat ground – but must be considered none-

theless a fortuitous and instructive coincidence.

Although inhabited from prehistoric times, this hilltop location was developed as a major city

only from ca. 300 BC. Lysimachos, one of the generals succeeding Alexander the Great, entrusted

a large part of his fortune to his officer Philetairos to guard at Pergamon. In 281 BC Lysimachos

was killed in battle. When no one contested the treasure, Philetairos used this money, 9000 tal-

ents (estimated by George Bean in 1966 as the equivalent of £10 million) to entrench himself

on Pergamon’s hilltop. By adopting his nephew Eumenes as his son, he founded a dynasty that

would last until 133 BC. The Attalid kingdom soon expanded; at its height, after the territorial

gains that followed its victory (with the Romans) over Antiochus III at Magnesia in 190 BC, it

Figure 18.3 City plan, Pergamon

HELLENISTIC CITIES 291

controlled most of western Asia Minor – roughly the equivalent of the Lydian kingdom of the

sixth century BC. The Pergamenian kings viewed their capital as the cultural center of the Greek

world, the Athens of its day; following the Athenian model, Pergamon became a major center

for the visual arts. During the Roman period, the city continued in importance, its population

swelling to ca. 150,000 in the second century AD.

The Acropolis

As the administrative, religious, and cultural heart of the ancient city, the acropolis has been the

focus for archaeologists and tourists in modern times. The German Archaeological Institute,

excavating at Pergamon from 1878 to the present, devoted its earliest campaigns to the acropolis.

In recent years, archaeologists returned here to reconstruct portions of the Trajaneum, a major

post-Hellenistic temple dedicated to the deified Roman emperor Trajan, the building that now

dominates the skyline.

Fortifications, palaces, and the water supply

The hilltop forms a north–south arc, bowing out toward the east. Buildings are arranged in

three sectors, north, east, and west, with protection secured on the north; royal palaces on the

east; and a major shrine and the state library on the west. The vertiginous theater is nestled in

the western curve of the hill. The northernmost tip of the acropolis is naturally protected, with

the land dropping sharply. Here stood an arsenal or military storehouse of the third-second

centuries BC, and next to it a barracks. The outer wall of the barracks, part of the north-east

Hellenistic fortification wall, is particularly well preserved, with thirty-two courses of ashlar

masonry still in place, and, with its seemingly sheer drop, shows how well protected this citadel

once was.

To the south of the barracks, along the east edge of the citadel, first Philetairos, then his

successors, built palaces, four complexes in all, loosely connected. These palaces, preserved

only in ground plan, were large peristyle houses of the sort already standard in Greek domestic

architecture: rooms arranged around porticoed open-air courts; decoration included mosaic

floors. Cisterns, used for water storage, formed part of the sophisticated water supply system,

developed probably in the second century BC. Water was brought to the city in a triple pipeline

of terracotta pipes from a mountain source ca. 45km to the north. For the final ascent to the

citadel, pipes possibly of bronze or lead were used, buried underground, their ends held fast

by stone blocks cut with appropriately sized holes. Forced upwards under pressure, the water

reached a central reservoir on the citadel; from here it flowed to the palaces and then down the

hill to houses and public fountains and through the sewers. This water supply system was an

early example of the sort of hydraulic engineering project that the Romans would extensively

develop.

The Temple of Athena and commemorative sculpture

On the west curve of the acropolis lies the city’s earliest and most important temple. The Temple

of Athena, a Doric order temple of the fourth century

BC, offers some surprises: it is rather small