Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

222 GREEK CITIES

spread to other parts of Greece. Although fragmentary preservation has made it impossible to

track the process with precision, we can note the appearance of characteristic Doric features at

various temples of the early Archaic period.

The Temple of Apollo at Thermon, of ca. 630 BC, shows early evidence for the installation of

a Doric entablature. This temple had stone foundations, but its walls and columns were made

of mud brick and wood, now vanished. The entablature was evidently also of wood, since stone

parts have not been found. The use of the Doric order in the entablature is conjectured from a

series of terracotta metope plaques that have survived, painted with such mythological scenes as

Perseus and the Gorgon. A few, it is important to note, are wider than the majority; this differ-

entiation suggests that the builders of this temple had worked out a solution to the Doric corner

problem.

Symmetrical though the Doric order may seem, it does have one unresolved difficulty: how

should the corner triglyphs align with the column below? Normally every other triglyph is cen-

tered above a column. But if this principle is followed at the corner, the column capital will

protrude. On the other hand, if the column is pulled back beneath the architrave, triglyph and

column will no longer be aligned. At Thermon, a compromise was reached. The metopes at the

ends of the frieze were made wider than the others, thus pushing the corner triglyph out to sit

over the edge of the column.

The Temple of Hera at Olympia, ca. 600 BC, offered another solution to the Doric corner

problem. As at Thermon, this temple was built of mud brick and wood on stone foundations.

In contrast with the temple at Thermon, here the placement of the columns is known, and in

this lay the answer. The corner columns were contracted, that is, brought in slightly from the

proper corner position, set in closer to the next column instead of repeating the normal spac-

ing between columns. As a result, the end metopes could remain the same length as the others,

but the outer edge of the corner triglyph would align with the outer edge of the column below.

Over the centuries the wooden columns of this temple were replaced with stone versions, each

with its capital in the appropriately up-to-date style. The result must have been something of a

mishmash; even today one can see capitals of different sizes and styles. One wooden column

still stood in the second century AD when the Greek doctor and travel writer Pausanias visited

Olympia.

The temple was decorated as well with two large terracotta disks placed at the apex of the roof.

Acroteria, as such roof decorations were called, would become highly popular. They could include

human figures as well as abstract or floral motifs.

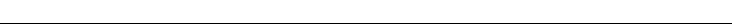

In contrast with the above temples, the superstructure of the Temple of Artemis at Kerkyra

(Corfu), ca. 600 BC, survives in ample fragments, demonstrating that the building was made of

stone. In addition to being the earliest stone temple, it was one of the largest, 49m × 23.5m. Like

the Temple of Hera at Olympia, this temple was laid out with the three standard rooms, pronaos,

cella, and opisthodomos (Figure 13.3). A double row of columns inside the cella assisted in sup-

porting the roof. The colonnade, 8 × 17 columns, was set well apart from the cella, allowing for a

second, inner colonnade which was never added. Since a double colonnade is known as a dipteral

arrangement, this version at Kerkyra, without the inner row, is called pseudo-dipteral. The pseudo-

dipteral plan allows for the extra size a dipteral plan offers, but saves money because the inner

columns are not built. Kerkyra displays the earliest example of this plan.

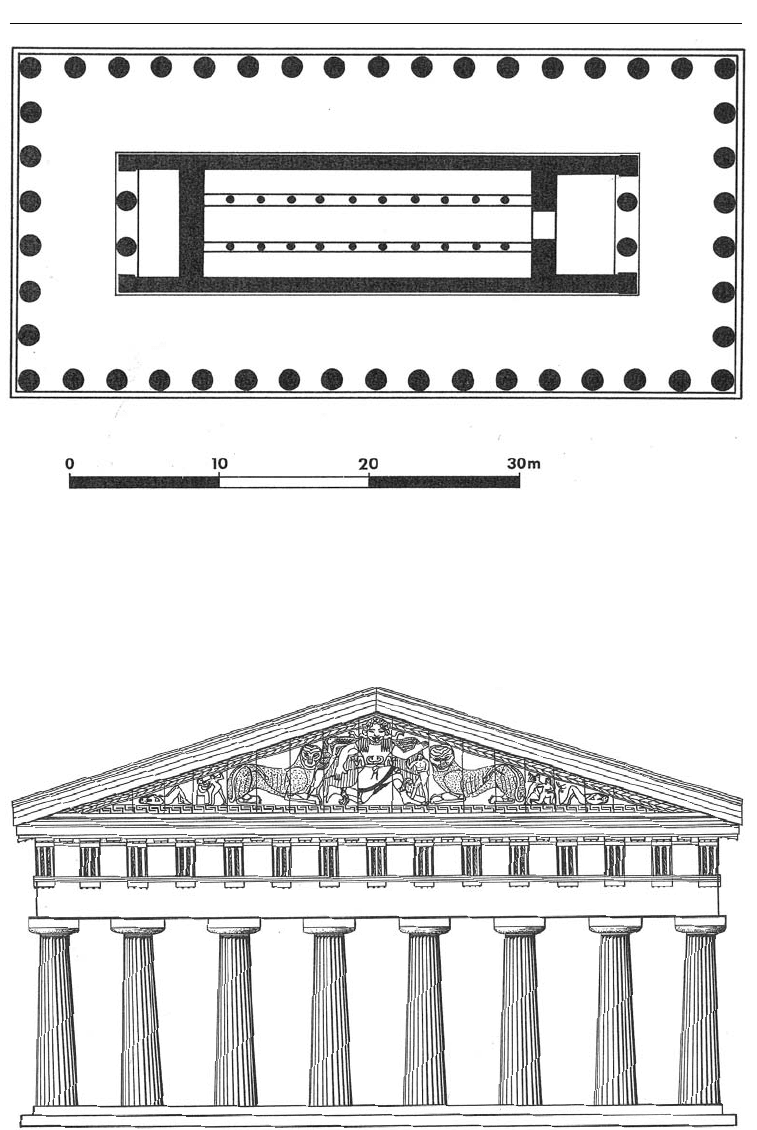

Sculptural decoration on the exterior of temples will become a hallmark of Greek cities and

sanctuaries, with the reliefs generally illustrating myths of local interest or of grand cosmologi-

cal concern. With the well-preserved sculptures from its west pediment, the temple at Kerkyra

gives us an early and striking example of this type of decoration (Figure 13.4). The huge figure of

ARCHAIC GREEK CITIES, I 223

Figure 13.3 Plan, Temple of Artemis, Kerkyra

Figure 13.4 Restored elevation, Temple of Artemis, Kerkyra

224 GREEK CITIES

the Gorgon Medusa, 2.79m in height, dominates the scene. The snake-haired Medusa had the

unfortunate gift of turning to stone anyone who looked at her. She was beheaded by the hero

Perseus, specially equipped by Athena and Hermes with a mirror to look indirectly at Medusa,

a sickle, a bag, Hades’s cap of darkness for invisibility, and winged shoes for a quick escape.

Medusa had a revenge of sorts: she would be esteemed by Greeks and Romans for her power to

ward off evil. Her face, an apotropaic talisman, was a prominent protecting image on their armor.

Indeed, her ability to frighten away danger may explain why this myth was chosen to decorate

the pediment.

In the Kerkyra pediment Medusa is shown with a round, mask-like face with a grotesque grin,

typical of her depiction in Archaic art. She is down on one knee in a pose that symbolizes run-

ning. Flanking her are two tiny, upright figures, her children, the human Chrysaor and the winged

horse Pegasus, and beyond them, two panthers who, like Medusa, snarl at those who approach

the temple. So far the figures have fit fairly well into the triangular space, but beyond the panthers

the rapidly descending ceiling creates problems for the artist. In scenes unrelated to Medusa and

on a far smaller scale, standing men spear kneeling and seated figures, and in the corner, two

men, fallen victims, lie on their backs, their knees drawn up to scrape the raking cornice. More

experimentation would be needed before sculptors could fill this awkward space with a scene

unified in scale and theme.

EARLY IONIC TEMPLES AT SAMOS AND EPHESUS

While the Doric order became standard on the Greek mainland and in West Greece, the

Ionic style was preferred in East Greece. Eventually the two merged in the later fifth century

BC on the Athenian Acropolis, as we shall see. The earliest temples clearly in the Ionic style

date from the second quarter of the sixth century BC. In addition, they are colossal, ca. 100m

× 50m. None survives well, unfortunately (with the exception of the later Temple of Apollo at

Didyma), since they served as convenient sources of cut stone for medieval and later building

projects.

At the Samian Heraion, architects Rhoikos and Theodoros constructed the third major Tem-

ple to Hera above the seventh-century BC temple. The huge plan, 102m × 51m, included a double

colonnade with eight columns on the front, ten on the back, and twenty-one on the sides. The

interior rooms consisted of a pronaos and cella only, each with two rows of columns. Accom-

panying the temple was a new altar, the first in the Ionic style. Since the Ionic order permitted

taller, slenderer proportions than the Doric, the columns could rise high. This multitude of tall

columns arranged like a forest must have produced an overpowering effect on the viewer. This

temple and the contemporary Temple of Artemis at nearby Ephesus were built on low ground,

both originally by the sea, undramatic settings that perhaps promoted the development of such

majestic designs.

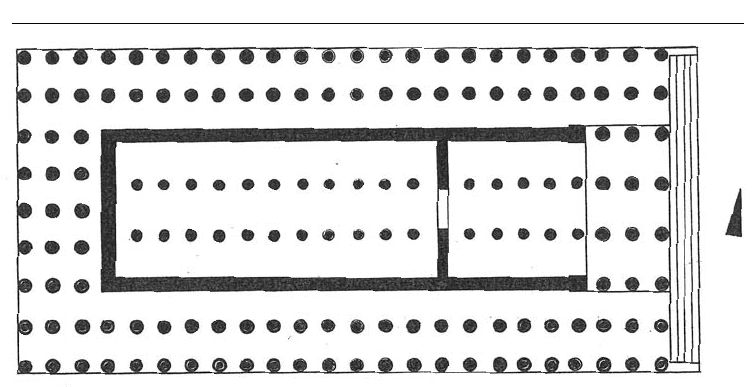

The third temple of Hera was burned ca. 530 BC. A fourth and final version was begun by the

tyrant Polykrates in the 520s. Work continued into the Roman period, but the temple was never

finished. The Polykratean temple was slightly larger than its predecessor, with three rows of eight

columns on the east end, three rows of nine on the west, and two rows of twenty-four on the

long sides (Figure 13.5).

At Ephesus on the Anatolian mainland an enormous Temple to Artemis was begun ca. 560

BC.

This, too, replaced earlier, smaller temples. The temple was designed by Chersiphron of Knossos

and his son Metagenes. Like Theodoros of Samos, they wrote a treatise about their project. Now

ARCHAIC GREEK CITIES, I 225

lost, these books were perhaps known to Vitruvius, the Roman architect of the first century BC

whose own book on Greek and Roman architecture has survived to the present day.

The temple measured ca. 115m × 51m, and according to tradition was built on foundations of

alternating layers of charcoal and fleece in order to counteract the effects of the marshy ground.

Its entrance lay on the west instead of the usual east; the western entrance is seen elsewhere in

West Anatolian temples, however, probably a survival from earlier worship of the Anatolian

mother goddess with whom the Greek Artemis was combined. Like its contemporary on Samos,

this temple was dipteral. On the front, it had three rows of eight columns; in the rear, two rows

of nine. Certain columns displayed an unusual feature: their lower drums were sculpted with

figures. This distinctive gift was the offering of Croesus, king of Lydia, renowned for his wealth

and for his love of Greek culture. The temple was burned in 356 BC, on the night of the birth of

Alexander the Great, so it was said, by one Herostratus, an arsonist whose sole, and successful,

aim was to make his name immortal. In the Hellenistic period the temple was rebuilt on a simi-

larly grand scale.

Today one can appreciate only the dimensions of the Artemision, marked by scattered marble

ruins and one re-erected column (often selected by a stork as an ideal nesting spot), in marshy

ground on the outskirts of the modern town of Selçuk. Behind the waterlogged ruins lies a

remarkable story of archaeological discovery. Although Hellenistic critics included this famous

temple among their Seven Wonders of the World, it had completely disappeared by modern

times. Earthquakes and reuse of its fine ashlar masonry for medieval building projects destroyed

the temple; layers of silt carried down from the hills by the Cayster River buried the site. In the

nineteenth century an Englishman, John Turtle Wood, set out to find the temple. The location of

the Roman city was known, but the temple lay hidden somewhere outside its walls, somewhere

in the marshy fields in what had become quite an isolated region. Wood searched in vain from

1863 to 1874. Eventually, a fragmentary stone inscription found in the Roman theater provided

the key. According to the inscription, sacred images were to be brought from the Temple of

Artemis to the theater, to be present during performances or assemblies. The route from the

temple was specified: along the Sacred Way that led to the Magnesian Gate. Wood then located

the Magnesian Gate and followed the marble paved street, buried well below the surface, from

the city to the temple.

Figure 13.5 The fourth Temple of Hera, Samian Heraion

226 GREEK CITIES

EAST GREEK CITIES IN THE ARCHAIC PERIOD: SAMOS,

MILETUS, AND THE IONIAN REVOLT

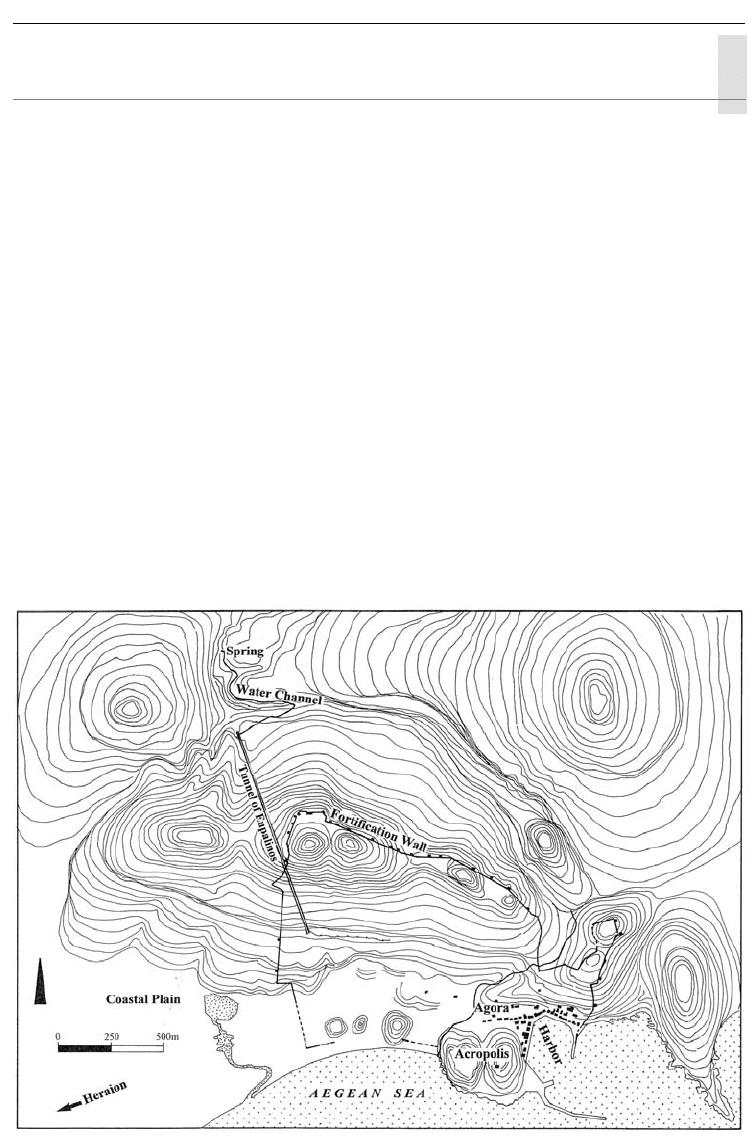

A good example of an East Greek city in the Archaic period is Samos, the capital of the island

of the same name. This city lay 6.5km east of the Heraion, on the site of the modern port of

Pithagorio (Tigani). During the rule of the tyrant Polykrates (538–522 BC), the city was a regional

power, economically strong and endowed with an effective fleet. Prosperity came not only from

the Heraion, a major pilgrimage site, but also from the fertile land, with its wine enjoying consid-

erable fame. The city itself underwent much new building. Although most has disappeared, the

visitor can still appreciate the general layout (Figure 13.6). The harbor was the focus, although its

piers, serving both commercial and military needs, have gone. Also gone is Polykrates’s palace

from its commanding position on the acropolis. Remains of the city’s fortification wall survive,

however, 6.7km long, still with gates and towers. And one can even walk through most of the

Tunnel of Eupalinos, the most famous of the Polykratean building projects. The 1km-long tun-

nel, one section of an aqueduct that brought water to the city from an inland spring, was bored

through the mountain behind the town. The tunneling began simultaneously at each end, with

the two sections eventually joining with a small degree of error. This feat of engineering, unparal-

leled in its time, was overseen by Eupalinos of Megara. The fortifications, the protected water

supply, and the fleet marked the efforts of Polykrates to protect Samos from an attack by the Per-

sians. But these precautions were ultimately unsuccessful: in 519 BC, after the death of Polykrates,

the Persians captured the city.

Figure 13.6 City plan, ancient Samos

ARCHAIC GREEK CITIES, I 227

The physical remains of other towns from Archaic East Greece are not so well known. Accord-

ing to ancient Greek literary sources, however, this region distinguished itself for its commer-

cial and intellectual achievements. The city of Miletus to the south of Ephesus was particularly

prominent. Located on a small mitten-shaped peninsula jutting into the Aegean and on nearby

hills, Miletus grew prosperous from maritime trade. She was one of the great colonizing cities,

with some ninety foundations to her name, especially in the Hellespont, Sea of Marmara, and

Black Sea regions. Among her citizens were Thales, Anaximenes, and Anaximander, important

pioneers in philosophy and science. This brilliant epoch came to an end in 494 BC, with the col-

lapse of the Ionian Revolt against Persian control.

Under Cyrus the Great, the Achaemenid Persians had expanded westwards into Anatolia in

the middle of the sixth century BC. In 546 BC they defeated the Lydians, the major power of West

Anatolia, capturing Sardis, their capital, and Croesus, their king. The Greek city-states of the

coast, incapable of uniting against the threat, quickly fell to Cyrus. But Persian control proved

loose, and apart from paying tribute, the Greek cities were given considerable autonomy to gov-

ern themselves. In 499 BC this compromise arrangement was wrecked when Aristagoras, the

tyrant of Miletus, led an uprising against the Persians and, with the help of the Athenians, burned

the provincial capital of the Persians at Sardis. The Ionian cities could not capitalize on this act

of defiance, however, and were no match for the sharp Persian reaction. In 494 BC, the revolt

ended with a Persian naval victory off the island of Lade and the capture and sack of Miletus.

Most Milesian men were killed, the women and children taken into slavery. This event was con-

sidered such a catastrophe for the Greek world that when a tragedy about the fall of Miletus was

produced in Athens, the audience burst into tears and the author was fined for provoking undue

emotional distress.

The Ionian Revolt had major consequences for the rest of Greece as well. Athens had partici-

pated in the raid on Sardis, but so far had escaped punishment. “Master, remember the Athe-

nians!” a servant of the Persian king Darius was commanded to whisper daily into the royal ear.

In 490 BC, the Persians set out to extract revenge.

CHAPTER 14

Archaic Greek cities, II

Sparta and Athens

During the Archaic period, ca. 600–479 BC, a general prosperity among city-states created a bal-

ance of strength and influence between regions. By the second quarter of the fifth century BC,

power had concentrated in the hands of two: Athens and Sparta. At the end of the century they

would fight each other in the Peloponnesian War, a protracted, draining conflict that finished

with the defeat of Athens. The character of Athenian society differed dramatically from that

of Sparta. Indeed, that Greek culture produced two such contrasting city-states has fascinated

observers from antiquity to the present day. Although Sparta has contributed only modestly to

the archaeological evidence for ancient Greece, its historical importance calls for a brief look at

the nature of its society. We shall then turn to Athens, to its pre-Classical political development

and to its important art and architectural remains.

SPARTA

Sparta was unique. Located in a fertile plain in the south-east Peloponnesus, by the early sev-

enth century BC Sparta had conquered not only Laconia, its home region, but also the south-

west province of Messenia, thereby amassing an unusually large territory for a Greek city-state.

Full citizenship was restricted to Spartans proper, although they formed only a small percentage

of the total population. The subject peoples included the perioikoi, in effect citizens with lesser

rights, autonomous in their villages but with little say in the state government, yet eligible to serve

in the army, and the helots, tenant farmers or serfs without any rights. While these last worked

the farms owned by the citizens, the male citizens devoted their energies to training for warfare.

In maintaining their military readiness, the Spartans’ first goal may have been to keep their own

subjects in line, the second to ward off enemies. In both they were successful: for several centu-

ries until their stunning defeat at Leuctra in 371 BC the Spartans fielded the finest infantry in the

Greek world.

During the Archaic and Classical periods, writers had no place in this society, so all reports

about Sparta were written by outsiders, men from other city-states. As a result, sorting through

the biases and finding the reality of Spartan society has been a challenge for generations of histo-

rians. It seems clear, however, that during the sixth century BC, Spartan daily life became distinctly

austere. Men lived in barracks until age 30, even when married, and thereafter ate together in mess

halls. Women also trained physically, to ensure the birth of strong children. Group solidarity was

all important. Individuality was discouraged, products of creativity such as fine arts restricted.

Even money was regarded as corrupting. Coinage was not issued; iron bars served as the medium

of exchange, when required. The world outside Sparta was regarded with deep suspicion.

The system of government remained essentially an oligarchy, continuing with little change

from the later Iron Age through the Classical period. Although there was an assembly of citizens,

ARCHAIC GREEK CITIES, II 229

important decisions were taken by smaller bodies, five ephors and a council of elders, including

two hereditary kings, relics from the past, who had authority in times of war.

The city itself has left few ruins. In one of the famous object lessons an ancient writer has left

modern archaeologists, Thucydides, the historian of the Peloponnesian War, remarked that build-

ings alone do not indicate a city’s greatness. No one would ever guess that dull Sparta was the

equal of Athens with its magnificent architecture. One must wonder what mistakes we have made

in the interpretation of prehistoric cultures, simply by ranking settlements according to size.

ATHENS IN THE ARCHAIC PERIOD

In contrast, Athenian writers flourished, leaving detailed accounts of their city’s society and his-

tory. Athens followed a line of development different from that of Sparta, one that led toward a

democracy in which its male citizens had an equal voice. By the late seventh century, the city-state

of Athens controlled the entire region of Attica. Class conflicts raged. Solon, a famous wise man

elected archon, or magistrate acting as head of state, for the year 594 BC, attempted to solve them

with a revision of the constitution and law code in which the debt-laden peasant farmers were

championed against the rich. The farmers’ crippling debts were canceled, but to soothe the other

side, the privilege to hold high office was still reserved for wealthy landholders.

These reforms did not eradicate class tension. In subsequent years resentment increased

between the people of the interior and the coast dwellers, with the former supporting Peisistratos

in his attempts to seize the polis. Eventually successful, Peisistratos, a benevolent tyrant, ruled

from ca. 560–527 BC. His sons proved less congenial. One, Hipparchos, was murdered in 514

BC, the other, Hippias, overthrown in 510 BC. A new leader came to the fore, Kleisthenes, who

organized the citizenry into ten artificial tribes, each with city, coastal, and interior contingents.

Each tribe sent fifty men to a “Council of 500.” A prytany, or portion of the council, took care of

daily affairs for a period of thirty-six days. In addition, the Popular Assembly continued, open to

all citizens, as did the Areopagus, the open-air jury court. These developments of the late Archaic

period marked the maturing of Athenian democracy and would continue in force for almost 200

years, until the Macedonians took control of the city in the later fourth century BC.

In developments in architecture and art Athens played a seminal role, again in striking contrast

with Sparta. Although Athens is best known for its fifth-century BC buildings, much remains

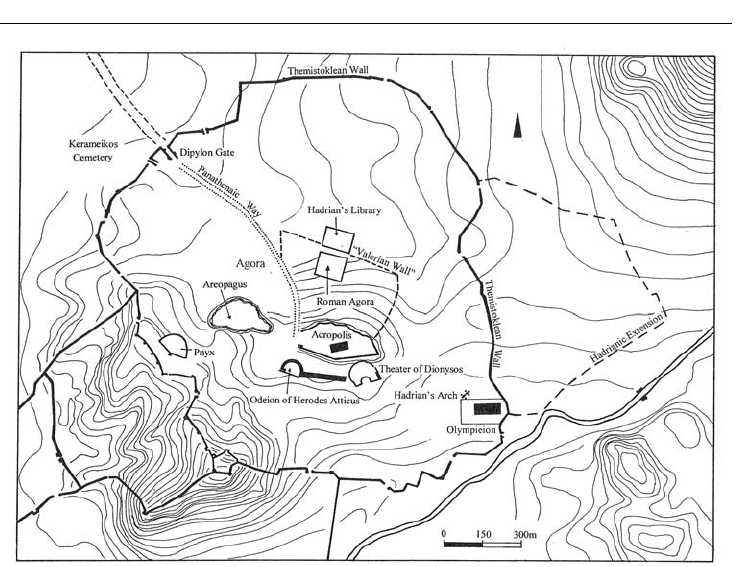

from the Archaic period (Figure 14.1). The center of the city is dominated by two hills. On the

Pnyx, the smaller of the two, the Popular Assembly held its meetings. The larger hill immediately

to the east, the Acropolis, or “high city,” had been the fortified center of the city since the Bronze

Age. By the sixth century BC, the Acropolis was turning into a religious sanctuary, the home of

Athena, the patron goddess of the city, and a host of other deities. Sixth-century BC temples

include two predecessors to the famous fifth century BC Parthenon (one in the mid-sixth century,

then a replacement in the 480s); a Temple to Athena Polias (Athena worshipped specifically as

the goddess of the city), built by the tyrant Peisistratos; and a series of treasuries (storehouses

for precious religious offerings) of which only striking but fragmentary sculptural decoration

survives. The outdoor spaces of this hilltop sanctuary would have contained many free-standing

life-size sculptures, votive offerings to the goddess (see below).

An additional cult center of importance was planned for a site to the south-east of the Acropo-

lis. Here Peisistratos laid foundations for a monumental Temple to the Olympian Zeus (= the

Olympieion), but he never finished it. Resumption of construction had to wait until the second

century BC, with the temple eventually completed by the Roman emperor Hadrian in the second

century AD.

230 GREEK CITIES

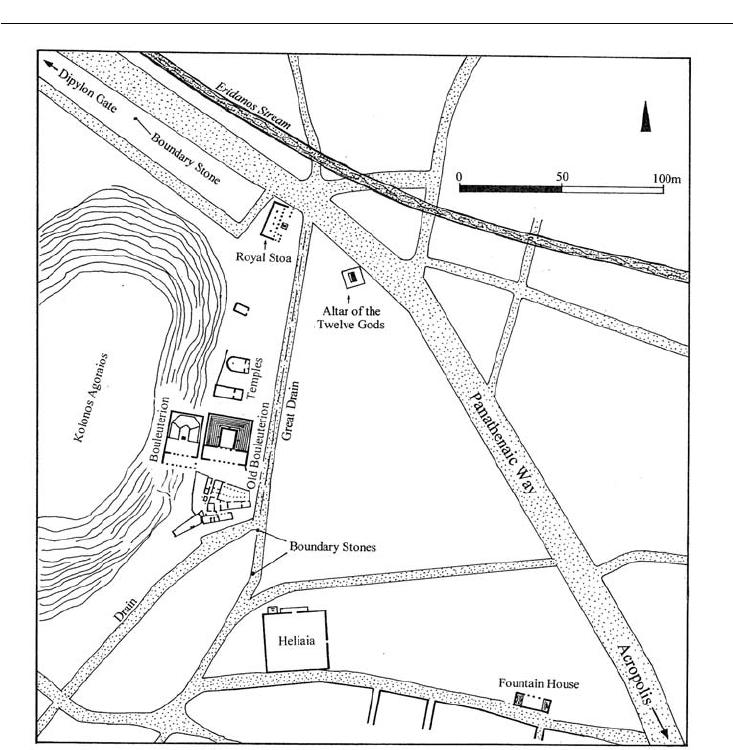

The city’s civic center, the Agora, situated on low ground north of the Acropolis, took on this

secular role during the early Archaic period; previously this land had served variously for hous-

ing and for burials (Figure 14.2). Its territory had precise borders, which ca. 500 BC were offi-

cially marked by boundary stones inscribed with the phrase “I am the boundary of the Agora.”

Although not a sanctuary, the Agora was endowed nonetheless with a certain sanctity. Basins

for holy water, perirrhanteria, were placed at its entrances, reminders that the public functions

taking place in the Agora often had a religious cast. For those who might sully the dignity of

the precinct, entry was forbidden. The fourth-century BC orator Aeschines could thus remark:

“So the lawmaker keeps outside the perirrhanteria of the Agora the man who avoids military

service, or plays the coward or deserts, and does not allow him to be crowned nor to enter public

shrines”; and his contemporary, Demosthenes: “Surely those who are traitors to the common-

wealth, those who mistreat their parents, and those who do not have clean hands, do wrong by

entering the Agora” (Camp 1986: 51).

A variety of functions took place in the Agora, some connected with buildings, some not.

With a brief tour of the area we can get an idea of the institutions of Athenian city life during the

Archaic period. By the end of the sixth century BC, important civic buildings lined the foot of the

low hill on the west, the Kolonos Agoraios, thereby giving architectural definition to the western

edge of the Agora. Among the most significant were the small Royal Stoa and the Old Bouleu-

terion. In the former, a structure originally of the late sixth century BC, the basileus, the second

highest official of the city and the overseer of religious observances, had his base. At a later date,

ca. 400

BC, the law codes of the city, inscribed on stone slabs, would be set up on the walls for the

public to inspect. The Old Bouleuterion, a square building with seating on three sides, dated to

ca. 500 BC, housed the Council of 500 set up by the reforms of Kleisthenes.

Figure 14.1 City plan, Athens, Iron Age through the Roman Empire

ARCHAIC GREEK CITIES, II 231

The south edge of the Agora was defined by the Heliaia (mid-sixth century BC), an open-air

law court, the largest in Athens, and the Southeast Fountain House, whose large basins of water

were supplied from sources north-east of the city by means of clay pipes.

The north and east sides of the Agora were not yet defined by buildings. The central space was

used at this time for gatherings of various sorts, including theatrical performances and athletic

contests, both occurring under the umbrella of religion, and for market stalls. The most impor-

tant monument here was the Altar of the Twelve Gods, identified by an inscribed statue base.

Dedicated in 522 BC under the Peisistratids, this altar marked the center of the city from which

distances were measured, and served as a recognized haven for those seeking refuge. Close by

the Altar of the Twelve Gods the Panathenaic Way crossed the Agora on the diagonal. This

route from the Dipylon Gate was used for the great procession up to the Acropolis during the

Panathenaia, the annual festival to Athena.

The most important civic buildings would be in place in the Agora by ca. 400

BC. The area

continued as the civic center through the Roman Empire, with many changes made to its

Figure 14.2 Plan, Agora, Athens, ca. 500 BC