Gary Nichols. Sedimentology and Stratigraphy(Second Edition)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4.9 SEDIMENTARY STRUCTURES AND

SEDIMENTARY ENVIRONMENTS

Bernoulli’s equation, Stokes Law, Reynolds and

Froude numbers may seem far removed from sedi-

mentary rocks exposed in a cliff but if we are to

interpret those rocks in terms of the processes that

formed them a little knowledge of fluid dynamics is

useful. Understanding what sedimentary structures

mean in terms of physical processes is one of the

starting points for the analysis of sedimentary rocks

in terms of environment of deposition. Most of the

sedimentary structures described are familiar from

terrigenous clastic rocks but it is important to remem-

ber that any particulate matter interacts with the fluid

medium it is transported in and many of these fea-

tures also occur commonly in calcareous sediments

made up of bioclastic debris and in volcaniclastic

rocks. The next chapter introduces the concepts used

in palaeoenvironmental analysis and is followed by

chapters that consider the processes and products of

different environments in more detail.

FURTHER READING

Allen, J.R.L. (1982) Sedimentary Structures: their Character

and Physical Basis, Vol. 1. Developments in Sedimentology.

Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Allen, J.R.L. (1985) Principles of Physical Sedimentology.

Unwin-Hyman, London.

Allen, P.A. (1997) Earth Surface Processes. Blackwell Science,

Oxford, 404 pp.

Collinson, J., Mountney, N. & Thompson, D. (2006) Sedimen-

tary Structures. Terra Publishing, London.

Leeder, M.R. (1999) Sedimentology and Sedimentary Basins:

from Turbulence to Tectonics. Blackwell Science, Oxford.

Pye, K. (Ed.) (1994) Sediment Transport and Depositional Pro-

cesses. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford.

68 Processes of Transport and Sedimentary Structures

Nichols/Sedimentology and Stratigraphy 9781405193795_4_004 Final Proof page 68 26.2.2009 8:16pm Compositor Name: ARaju

5

Field Sedimentology, Facies

and Environments

The methodology of analysing sedimentary rocks, recording data and interpreting them

in terms of processes and environments are considered in a general sense in this

chapter. Geology is like any other science: the value of the interpretations that come

from the results is determined by the quality of the data collected. The description of

rocks in hand specimen and thin-section has been considered in previous chapters, but a

very high proportion of the data used in sedimentological analysis comes from fieldwork,

during which the characteristics of strata are analysed at a larger scale. The character of

sediment in any depositional environment will be determined by the physical, chemical

and biological processes that have occurred during the formation, transport and deposi-

tion of the sediment. In the subsequent chapters the range of depositional environments

is considered in terms of the processes that occur in each and the character of the

sediment deposited. By way of introduction to these chapters the concepts of deposi-

tional environments and sedimentary facies are considered here. The examples used

relate to processes and products in environments considered in more detail in subse-

quent chapters.

5.1 FIELD SEDIMENTOLOGY

A large part of modern sedimentology is the interpre-

tation of sediments and sedimentary rocks in terms of

processes of transport and deposition and how they

are distributed in space and time in sedimentary

environments. To carry out this sort of sedimentolo-

gical analysis some data are required, and this is

mainly collected from exposures of rocks, although

data from the subsurface are becoming increasingly

important (2.2). A satisfactory analysis of sedimen-

tary environments and their stratigraphic context

requires a sound basis of field data, so the first part

of this chapter is concerned with practical aspects of

sedimentological fieldwork, followed by an introduc-

tion to the methods used in interpretation.

5.1.1 Field equipment

Only a few tools are needed for field studies in sedi-

mentology and stratigraphy. A notebook to record

data is essential and a strong hard-backed book

made with weather-resistant paper is strongly recom-

mended. Also essential is a hand lens (10 magni-

fication), a compass–clinometer and a geological

hammer. If a sedimentary log is going to be recor-

ded (5.2), a measuring tape or metre stick is also

essential and if proforma log sheets are to be used, a

clipboard is needed. For the collection of samples,

small, strong, plastic bags and a marker pen are

necessary. A small bottle containing dilute hydro-

chloric acid is very useful to test for the presence of

calcium carbonate in the field (3.1.1). It is good to

have some form of grain-size comparator. Small cards

with a printed visual chart of grain sizes can be

bought, but some sedimentologists prefer to make a

comparator by gluing sand of different grain sizes on

to areas of a small piece of card or Perspex. The

advantage of these comparators made with real

grains is that they make it possible to compare by

touch as well as visually.

The most ‘hi-tech’ items taken in the field are likely

to be a camera and a GPS (Global Positioning Satel-

lite) receiver. Photographs are very useful for provid-

ing a record of the features seen in the field, but only

if a note is kept of where every photograph was

taken, and it is also important that supplementary

sketches are made. Global Positioning Satellite recei-

vers have become standard equipment for field geol-

ogists, and can be a quick and effective way of

determining locations. They are used alongside a

compass–clinometer, and are not a replacement for

it: a GPS unit will not normally have a clinometer on

it, and a compass will work without batteries.

5.1.2 Field studies: mapping and logging

The organisation of a field programme of sedimentary

studies will depend on the objectives of the project.

When an area with sedimentary rock units is mapped

the character of the beds exposed in different places

is described in terms used in this book. To describe

the lithology the Dunham classification (3.1.6) can

be used for limestones, and the Pettijohn classifica-

tion for sandstones (2.3.3). Other features to be noted

are bed thicknesses, sedimentary structures, fossils

(both body and trace fossils – 11.7), rock colour and

any other characteristics such as weathering, degree

of consolidation and so on. Field guides such as

Tucker (2003) and Stow (2005) provide a check-list

of features to be noted. Once different formations have

been recognised (19.3.3) it is normal for a graphic

sedimentary log (5.2) to be measured and recorded

from a suitable location within each formation.

Although it is sufficient to regard a rock unit as simply

‘red sandstone’ for the purposes of drawing a geologi-

cal map, any report accompanying the map should

attempt to reconstruct the geological history of the

area. At this stage some knowledge of the detailed

character of the sandstone will be required, and suffi-

cient information will have to be gathered to be able

to interpret the sandstone in terms of environment of

deposition (5.7).

An in-depth study may involve recording a lot of

data from sedimentary rocks, either to see how a

particular unit may vary geographically, or to see

how the sedimentary character of a unit varies verti-

cally (i.e. through time) – or both. The data for these

palaeoenvironmental (5.7) or stratigraphic (Chapter

19) studies need to be collected in a systematic and

efficient way, and for this purpose the graphic sedi-

mentary log is the main method of recording data. A

sedimentologist may spend a lot of time recording and

drawing these logs, in conditions which vary from

sunny beaches to wind-swept mountainsides (or

even a warehouse in an industrial city – 22.3), but

the methodology is essentially the same in every

instance. In conjunction with the data recorded on

logs, other information such as palaeocurrent data

will be collected, along with samples for petrographic

and palaeontological analyses.

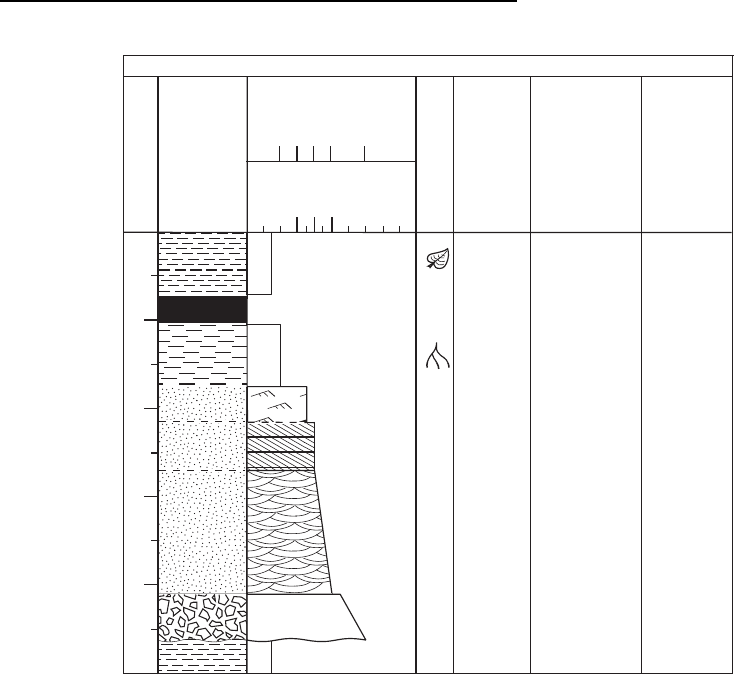

5.2 GRAPHIC SEDIMENTARY LOGS

A sedimentary log is a graphical method for rep-

resenting a series of beds of sediments or sedimen-

tary rocks. There are many different schemes in use,

but they are all variants on a theme. The format

presented here (Fig. 5.1) closely follows that of Tucker

(1996); other commonly used formats are illus-

trated in Collinson et al. (2006). The objective of

any graphic sedimentary log should be to present

the data in a way which is easy to recognise and

interpret using simple symbols and abbreviations

that should be understandable without reference to

a key (although a key should always be included to

avoid ambiguity).

70 Field Sedimentology, Facies and Environments

5.2.1 Drawing a graphic sedimentary log

The vertical scale used is determined by the amount of

detail required. If information on beds a centimetre

thick is needed then a scale of 1:10 is appropriate. A

log drawn through tens or hundreds of metres may be

drawn at 1:100 if beds less than 10 cm thick need not

be recorded individually. Intermediate scales are also

used, with 1:20 and 1:50 usually preferred in order to

make scale conversion easy. Summary logs that pro-

vide only an outline of a succession of strata may be

drawn at a scale of 1:500 or 1:1000.

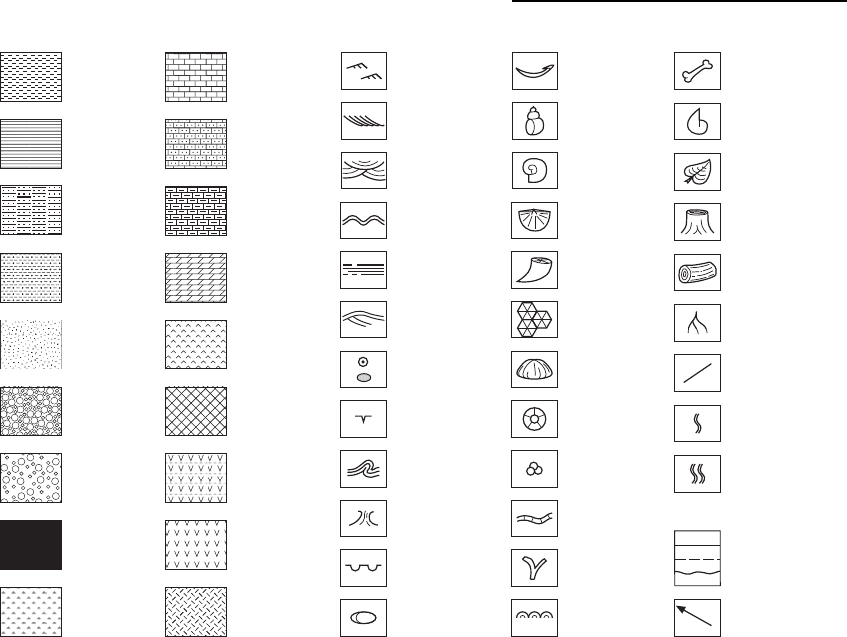

Most of the symbols for lithologies in common use

are more-or-less standardised: dots are used for sands

and sandstone, bricks for limestone, and so on

(Fig. 5.2). The scheme can be modified to suit the

succession under description, for example, by the

superimposition of the letter ‘G’ to indicate a glau-

conitic sandstone, by adding dots to the brickwork

to represent a sandy limestone, and so on. In many

schemes the lithology is shown in a single column.

Alongside the lithology column (to the right) there is

space for additional information about the sedi-

ment type and for the recording of sedimentary

structures (see below). A horizontal scale is used to

indicate the grain size in clastic sediments. The

Dunham classification for limestones can also be

represented using this type of scale. This scheme

gives a quick visual impression of any trends

in grain size in normal or reverse graded beds, and

in fining-upwards or coarsening-upwards successions

of beds.

Low energy,

vegetated

4

3

2

1

LIMESTONES

mud

wacke

pack

grain

rud &

bound

MUD

clay

silt

vf

SAND

f

m

c

vc

GRAVEL

gran

pebb

cobb

boul

Example sedimentary log

SCALE (m)

LITHOLOGY

STRUCTURES

& FOSSILS

NOTES

PROCESS

INTERPRETATION

ENVIRONMENT

INTERPRETION

coal

Low energy,

vegetated

river

floodplain

ripple migration

_________________

60cm sets

palaeoflow

120, 175,

150, 160

arcuate dune

migration

scour and fill

of river

channel

polymict scoured surface

dark low energy

20cm sets

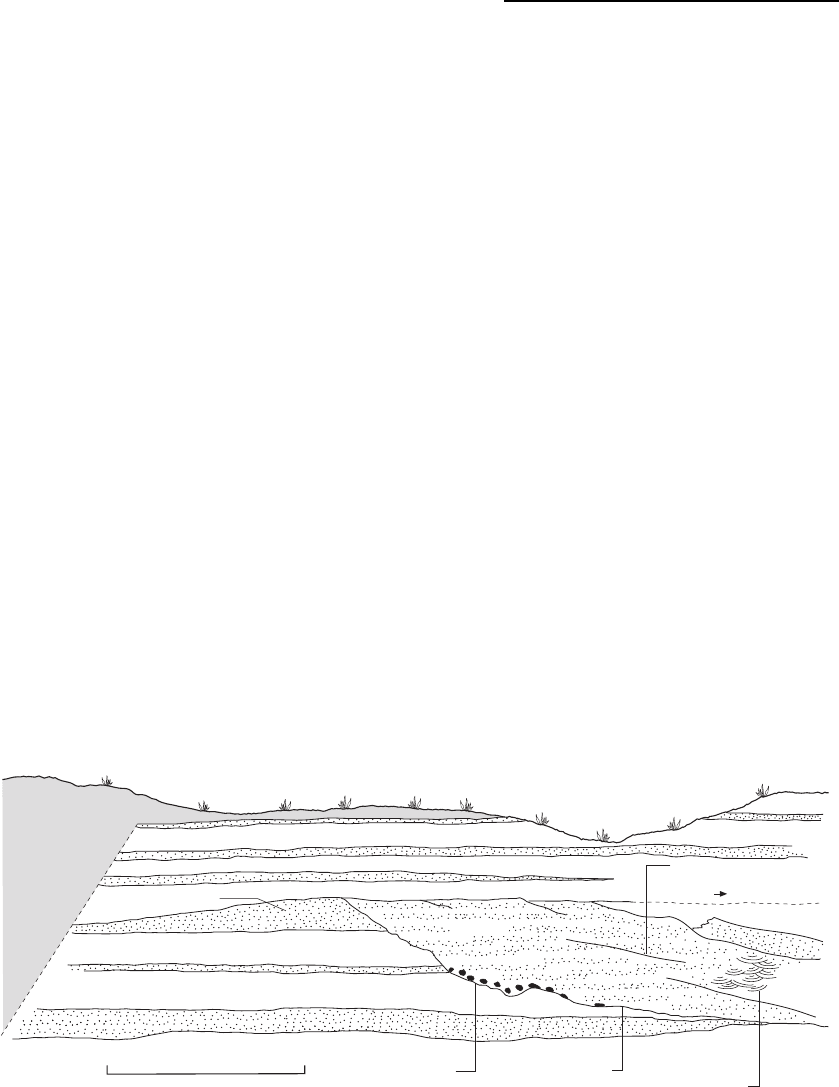

Fig. 5.1 An example of a graphic sedimentary log: this form of presentation is widely used to summarise features in

successions of sediments and sedimentary rocks.

Graphic Sedimentary Logs 71

By convention the symbols used to represent sedi-

mentary structures bear a close resemblance to the

appearance of the feature in the field or in core

(Fig. 5.2). This representation is somewhat stylised

for the sake of simplicity and, again, symbols can be

adapted to suit individual circumstances. Where

space allows symbols can be placed within the bed

but may also be drawn alongside on the right. Bed

boundaries may be sharp/erosional, where the upper

bed cuts down into the lower one, or transitional/

gradational, in which there is a gradual change

from one lithology to another. Any other details

about the succession of beds can also be recorded on

the graphic log (Fig. 5.1). Palaeocurrent data may

be presented as a series of arrows oriented in the

direction of palaeoflow measured or summarised for

a unit as a rose diagram (5.3.3) alongside the log.

Colour is normally recorded in words or abbreviations

and any further remarks or observations may be

simply written alongside the graphic log in an appro-

priate place.

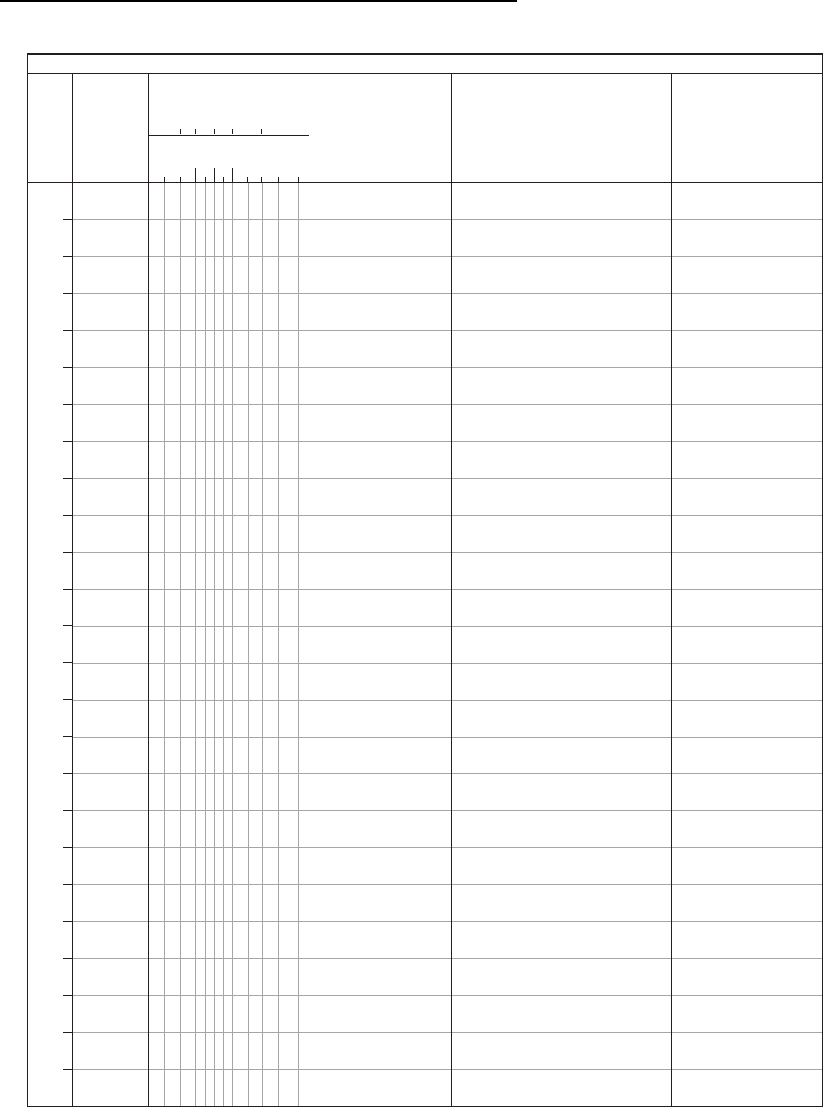

5.2.2 Presentation of graphic sedimentary

logs

It is common practise to draw a log in the field and

then redraft it at a later stage. The field log can be

drawn straight on to a proforma log sheet (such as

Fig. 5.3), but it can be more convenient to draw a

sketch log in a field notebook. The field log does not

have to be drawn to scale, but the thickness of every

bed must be recorded so that a properly scaled version

of the log can be drawn later. Sketch logs in the field

notebook are also a quick and convenient way of

recording sedimentological data, even when there

are no plans to present graphic logs in a report. As

is usually the case in geology, sketches and graphical

Ooids

Peloids

Mudcracks

Convolute beds

or lamination

Water escape

structures

Load casts

Nodules and

concretions

Sandstone

Siltstone

Vertebrates

Undifferentiated

fossil material

Plant material

Tree stumps

Logs

Roots

Indicates fragmented

material

Bioturbation

(moderate)

Bioturbation

(intense)

sharp

Bed boundaries:

gradational

erosional

Palaeocurrent

direction

Bivalves

Gastropods

Cephalopods

Brachiopods

Solitary corals

Colonial corals

Echinoids

Crinoids

Foraminifera

Algae

Bryozoa

Stromatolites

Current ripple

cross-lamination

Planar cross-

bedding

Trough cross-

bedding

Wave ripple

cross-lamination

Horizontal

lamination

Hummocky/swaley

cross-stratification

Limestone

(e.g. grainstone)

Limestone

(e.g. wackestone)

Dolomite

Gypsum or

anhydrite

Halite

Volcaniclastic

sediment

Volcanic rock

(lava)

Intrusive rock

Claystone

Shale

Mudstone

Conglomerate

(clast-support)

Conglomerate

(matrix-support)

Coal

Chert

Limestone

Fig. 5.2 Examples of patterns and symbols used on graphic sedimentary logs.

72 Field Sedimentology, Facies and Environments

REFERENCE:

LITHOLOGY

LIMESTONES

MUD SAND GRAVEL

TEXTURE

PROCESS

INTERPRETATION

ENVIRONMENT

INTERPRETATION

Grain size and

other notes

(structures,

palaeocurrents,

fossils, colour)

clay

silt

gran

peb

cob

boul

vf

f

m

c

vc

SCALE

mud

wacke

pack

grain

rud &

bound

Fig. 5.3 A proforma sheet for constructing graphic sedimentary logs.

Graphic Sedimentary Logs 73

representations of data, especially field data, are a

quicker and more effective way of recording informa-

tion than words. Interpretation of the information in

terms of processes and environment (facies analysis –

5.6.1) is normally carried out back in the laboratory.

Computer-aided graphic log presentation has

become widespread in recent years, including both

dedicated log drawing packages and standard draw-

ing packages (www.sedlog.com). These can provide

clear images for presentation purposes, and are used

in publications, but must be used with some care to

ensure that logs do not become over-simplified with

the loss of detailed information. For fieldwork, there is

no substitute for the graphic log drawn by pen and

pencil and the log drawn in the field must still be

considered to be the fundamental raw data.

A number of sedimentary logs can be presented on

a single sheet and linked together along surfaces of

correlation, using either lithostratigraphic or sequence

stratigraphic principles (see Chapters 19 and 23). These

fence diagrams can be simple correlation panels if

all the log locations fall along a line, but can also

be used to show relationships and correlations in

three-dimensions.

5.2.3 Other graphical presentations:

sketches and photographs

A graphic log is a one-dimensional representation of

beds of sedimentary rock that is the only presentation

possible with drill-core (22.3.2 ) and is perfectly ade-

quate for the most simple ‘layer-cake’ strata (beds that

do not vary in thickness or characteristics laterally).

Where an exposure of beds reveals that there is sig-

nificant lateral variation, for example, river channel

and overbank deposits in a fluvial environment, a

single, vertical log does not adequately represent the

nature of the deposits. A two-dimensional representa-

tion is required in the form of a section drawn of a

natural or artificial exposure in a cliff or cutting

(Fig. 5.4).

A carefully drawn, annotated sketch section show-

ing all the main sedimentological features (bedding,

cross-stratification, and so on) is normally satisfactory

and may be supplemented by a photograph. Photo-

graphs (Fig. 5.5) can be used as a template for a field

sketch, and now that digital cameras, laptops and

portable printers are all available, the image can be

produced in the field. However, a photograph should

never be considered as a substitute for a field sketch:

sedimentological features are rarely as clear on a

photograph as they are in the field and a lot of infor-

mation can be lost if important features and relation-

ships are not drawn at the time. A good geological

sketch need not be a work of art. Geological features

should be clearly and prominently represented while

incidental objects like trees and bushes can often be

ignored. All sketches and photographs must include a

scale of some form and the orientation of the view

must be recorded and annotated to highlight key

geological features.

5m

NE

SW

Crevasse splay?

Mudrocks with colour mottling (pedogenic?)

Rip-up clasts

Scoured

base of

channel

Trough

cross-bedding

(flow 110°)

Lateral accretion

surfaces

(dip 035°)

Channel

Overbank thin (~20cm) sandstone beds

Slumped

material

Fig. 5.4 An example of an annotated sketch illustrating sedimentary features observed in the field.

74 Field Sedimentology, Facies and Environments

Further information on the field description of sedi-

mentary rocks is provided in Tucker (2003) and Stow

(2005).

5.3 PALAEOCURRENTS

A palaeocurrent indicator is evidence for the direc-

tion of flow at the time the sediment was deposited,

and may also be referred to as the palaeoflow.

Palaeoflow data are used in conjunction with facies

analysis (5.6.2) and provenance studies (5.4.1)to

make palaeogeographic reconstructions (5.7). The

data are routinely collected when making a sedimen-

tary log, but additional palaeocurrent data may also

be collected from localities that have not been logged

in order to increase the size of the data set.

5.3.1 Palaeocurrent indicators

Two groups of palaeocurrent indicators in sedimen-

tary structures can be distinguished (Miall 1999).

Unidirectional indicators are features that give

the direction of flow.

1 Cross-lamination (4.3.1) is produced by ripples

migrating in the direction of the flow of the current.

The dip direction of the cross-laminae is measured.

2 Cross-bedding (4.3.2) is formed by the migration of

aeolian and subaqueous dunes and the direction of dip

of the lee slope is approximately the direction of flow.

The direction of dip of the cross-strata in cross-bedding

is measured.

3 Large-scale cross-bedding and cross-stratification

formed by large bars in river channels (9.2.1) and

shallow marine settings (14.3.1), or the progradation

of foresets of Gilbert-type deltas (12.4.2) is an indi-

cator of flow direction. The direction of dip of the

cross-strata is measured. An exception is epsilon

cross-stratification produced by point-bar accumula-

tion, which lies perpendicular to flow direction (9.2.2).

4 Clast imbrication is formed when discoid gravel

clasts become oriented in strong flows into a stable

position with one of the two longer axes dipping

upstream when viewed side-on (Fig. 2.9). Note that

this is opposite to the measured direction in cross-

stratification.

5 Flute casts (4.7) are local scours in the substrata

generated by vortices within a flow. As the turbulent

vortex forms it is carried along by the flow and lifted

up, away from the basal surface to leave an asym-

metric mark on the floor of the flow, with the steep

edge on the upstream side. The direction along the

axis of the scour away from the steep edge is mea-

sured.

Flow axis indicators are structures that provide

information about the axis of the current but do

not differentiate between upstream and downstream

directions. They are nevertheless useful in combina-

tion with unidirectional indicators, for example,

grooves and flutes may be associated with turbidites

(4.5.2).

1 Primary current lineations (4.3.4) on bedding

planes are measured by determining the orientation

of the lines of grains.

2 Groove casts (4.7) are elongate scours caused by

the indentation of a particle carried within a flow that

give the flow axis.

3 Elongate clast orientation may provide information

if needle-like minerals, elongate fossils such as belem-

nites, or pieces of wood show a parallel alignment in

the flow.

4 Channel and scour margins can be used as indica-

tors because the cut bank of a channel lies parallel to

the direction of flow.

5.3.2 Measuring palaeocurrents

The most commonly used features for determining

palaeoflow are cross-stratification, at various scales.

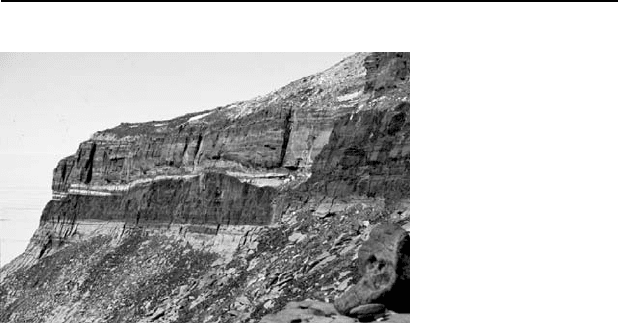

Fig. 5.5 A field photograph of sedimentary rocks: an irregular

lower surface of the thick sandstone unit in the upper part of

the cliff marks the base of a river channel.

Palaeocurrents 75

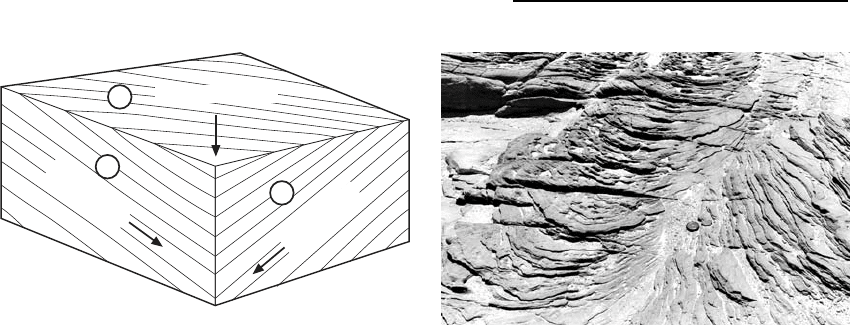

The measurement of the direction of dip of an inclined

surface is not always straightforward, especially if the

surface is curved in three dimensions as is the case

with trough cross-stratification. Normally an expo-

sure of cross-bedding that has two vertical faces at

right angles is needed (Fig. 5.6), or a horizontal sur-

face cuts through the cross-bedding (Fig. 5.7). In all

cases a single vertical cut through the cross-stratifica-

tion is unsatisfactory because this only gives an

apparent dip, which is not necessarily the direction

of flow.

Imbrication of discoid pebbles is a useful palaeoflow

indicator in conglomerates, and if clasts protrude

from the rock face, it is usually possible to directly

measure the direction of dip of clasts. It must be

remembered that imbricated clasts dip upstream, so

the direction of dip of the clasts will be 180 degrees

from the direction of palaeoflow (Figs 2.9 & 2.10).

Linear features such as grooves and primary current

lineations are the easiest things to measure by record-

ing their direction on the bedding surface, but they do

not provide a unidirectional flow indicator. The posi-

tions of the edges of scours and channels provide an

indication of the orientation of a confined flow: three-

dimensional exposures are needed to make a satisfac-

tory estimate of a channel orientation, and other

features such as cross-bedding will be needed to

obtain a flow direction.

The procedure for the collection and interpretation

of palaeocurrent data becomes more complex if the

strata have been deformed. The direction has to be

recorded as a plunge with respect to the orientation of

the bedding, and this direction must then be rotated

back to the depositional horizontal using stereonet

techniques (Collinson et al. 2006).

In answer to the question of how many data points

are required to carry out palaeocurrent analysis, it is

tempting to say ‘as many as possible’. The statistical

validity of the mean will be improved with more data,

but if only a general trend of flow is required for the

project in hand, then fewer will be required. A detailed

palaeoenvironmental analysis (5.7) is likely to require

many tens or hundreds of readings. In general, a

mean based on less than 10 readings would be con-

sidered to be unreliable, but sometimes only a few

data points are available, and any data are better

than none. Although every effort should be made to

obtain reliable readings, the quality of exposure does

not always make this possible, and sometimes the

palaeocurrent reading will be known to be rather

approximate. Once again, anything may be better

than nothing, but the degree of confidence in the

data should be noted. (One technique is to use num-

bers for good quality flow indicators, e.g. 2758, 2908,

etc., but use points of the compass for the less reliable

readings, e.g. WNW.)

There are several important considerations when

collecting palaeocurrent data. Firstly it is absolutely

essential to record the nature of the palaeocurrent

indicator that has been recorded (trough cross-bed-

ding, flute marks, primary current lineation, and

so on). Secondly, the facies (5.6.1) of the beds that

contain the palaeoflow indicators is also critical:

the deposits of a river channel will have current

True dip direction

Apparent dip

Apparent dip

T

A

B

Fig. 5.6 The true direction of dip of planes (e.g. planar

cross-beds) cannot be determined from a single vertical face

(faces A or B): a true dip can be calculated from two different

apparent dip measurements or measured directly from the

horizontal surface (T).

Fig. 5.7 Trough cross-bedding seen in plan view: flow is

interpreted as being away from the camera.

76 Field Sedimentology, Facies and Environments

indicators that reflect the river flow, but in overbank

deposits the flow may have been perpendicular to the

river channel (9.3). Lastly, not all palaeoflow indica-

tors have the same ‘rank’: due to the irregularities of

flow in a channel, a ripple on a bar may be oriented in

almost any direction, but the downstream face of a

large sandy or gravelly bar will produce cross-bedding

that is close to the direction of flow of the river. It is

therefore good practice to separate palaeoflow indica-

tors into their different ranks when carrying out anal-

yses of the data.

5.3.3 Presentation and analysis

of directional data

Directional data are commonly collected and used in

geology. Palaeocurrents are most frequently encoun-

tered in sedimentology, but similar data are collected

in structural analyses. Once a set of data has been

collected it is useful to be able to determine para-

meters such as the mean direction and the spread

about the mean (or standard deviation). The proce-

dure used for calculating the mean of a set of direc-

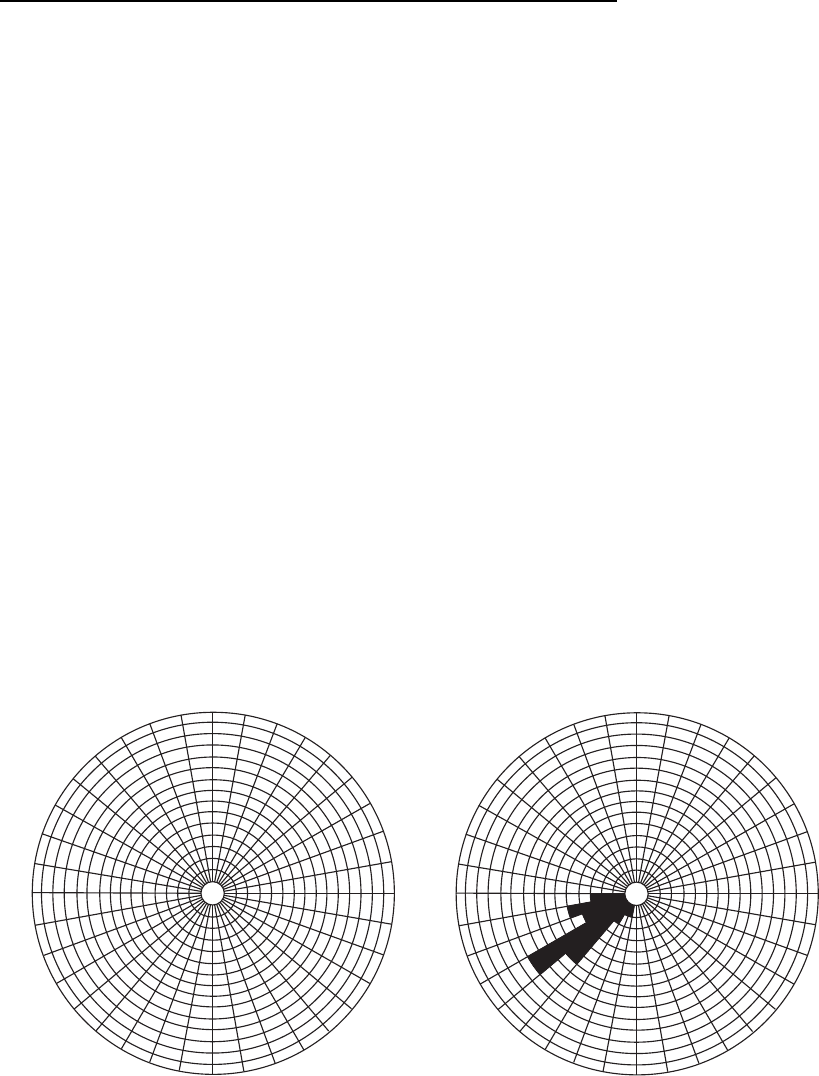

tional data is described below. Palaeocurrent data are

normally plotted on a rose diagram (Fig. 5.8). This is

a circular histogram on which directional data are

plotted. The calculated mean can also be added. The

base used is a circle divided up with radii at 108 or 208

intervals and containing a series of concentric circles.

The data are firstly grouped into blocks of 108 or 208

(0018–0208, 021–0408, etc.) and the number that

fall within each range is marked by gradations out

from the centre of the circular histogram. In this

example (Fig. 5.8) three readings are between 2618

and 2708, five between 2518 and 2608, and so on.

The scale from the centre to the perimeter of the circle

should be marked, and the total number ‘N’ in the

data set indicated.

5.3.4 Calculating the mean

of palaeocurrent data

Calculating the mean of a set of directional data is not

as straightforward as, for example, determining the

average of a set of bed thickness measurements.

Palaeocurrents are measured as a bearing on a circle

and determining the average of a set of bearings by

adding them together and dividing by the number of

readings does not give a meaningful result: to illus-

trate why, two bearings of 010 8 and 3508 obviously

have a mean of 0008/3608, but simple addition and

division by two gives an answer of 1808 , the opposite

(a) (b)

270

90

280

290

300

310

320

330

340

350

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

100

110

120

130

140

150

160

170

180

190

200

210

220

230

240

250

260

270

90

280

290

300

310

320

330

340

350

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

100

110

120

130

140

150

160

170

180

190

200

210

220

230

240

250

260

Fig. 5.8 A rose diagram is used to graphically summarise directional data such as palaeocurrent information:

the example on the right shows data indicating a flow to the south west.

Palaeocurrents 77