Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

IAN BOWLER

86

and indirect financial transfers under the CAP, for instance the Netherlands, Denmark and

Ireland; and (c) the labyrinthine policy-making process of the EU, its numerous ‘checks

and balances’ favouring incremental adjustments to the status quo rather than radical reform.

Thus the founding principles of the CAP were continued into the mid-1980s, including

maintaining common guaranteed prices above international market levels, intervention

buying of the main farm products, protection by variable levies against imports from non-

EU producers, and common funding. Running in parallel with price policies were measures

designed to raise the efficiency of farming. EU Regulations 17/64, 355/77 and 1932/84, for

example, offered grant aid to improve agricultural marketing and processing, while Directives

72/159, 72/160 and 72/161 sought to further modernise individual farm businesses, pay

early retirement pensions and provide socio-economic guidance and agricultural training to

farmers. Like their counterparts in the other member states, UK farmers responded by

increasing their output of production per hectare of farmland, particularly milk, wheat and

oilseed rape. By the early 1980s, however, the financial burden of agricultural support on

the member states had become so great as to threaten the very existence of the EU.

Consequently, during the 1980s, price support levels for all farm products were allowed to

fall in real terms by between 2 and 5 per cent each year, while expenditure from the European

Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund (EAGGF) was capped by a series of measures,

including co-responsibility levies, production quotas and maximum guaranteed quantities

(stabilisers).

The financial crisis facing the EU formed part of the context for a reregulation of

agriculture under the third food regime. In a broader context, however, reregulation should

be interpreted as a renegotiation of the relationship between the state and agriculture, not

just in the EU but internationally. Three arenas of renegotiation can be identified in a process

more accurately termed the ‘reregulation’ rather than ‘deregulation’ of agriculture: state

intervention in the market, agri-environmental relations and food quality/safety.

State intervention in the market

On the first arena, the member states of the EU are attempting to reduce their level of

intervention in the market for agricultural produce so as to: (a) reduce the output of ‘surplus’

farm products; (b) reduce the financial cost to the EAGGF of ‘productionist’ support policies;

and (c) open the market of the EU to global competition. The need to reduce, or at least limit

the increase in production of farm products underpinned a 1992 package of CAP measures,

commonly known as the ‘MacSharry reforms’ after the incumbent EU Commissioner for

Agriculture. These reforms cut the support prices of cereals by 29 per cent and beef by 15

per cent over three years, placed individual farm quotas on subsidies in the beef and sheep

sectors, reduced the price support on milk by 5 per cent but extended the time limit on the

1984 milk quota scheme, introduced area-based direct income payments for arable crops

(the Arable Area Payments Scheme in the UK—AAPs), made set-aside of arable land

compulsory for the receipt of the AAPs (cross-compliance) and introduced ‘accompanying

measures’ for the afforestation of farmland and early farmer retirement. In sum, an attempt

was made through direct income aids to decouple the link between farm incomes and the

volume of food produced. In practice intervention stocks and their associated costs have

fallen, while the burden of farm support has been shifted from consumers to taxpayers but

with little impact on the overall cost of the CAP.

AGRICULTURE

87

However, the MacSharry reforms must also be placed in the context of parallel

international disputes and negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

(GATT: now the World Trade Organisation—WTO). The EU had come under considerable

political pressure from the United States and the ‘Cairns Group’ of primary produce exporting

countries to reduce the level of protection afforded to its agricultural sector. Negotiations

leading up to the conclusion of the Uruguay Round in 1993, therefore, shaped the outcome

to the MacSharry reforms and began the process of opening EU agriculture to global

competition through a significant lowering, if not total elimination, of barriers to trade with

food producers from outside the EU. Food wholesalers, processors and retailers in the UK,

as well as the other member states, now have increasing access to lower-cost sources of raw

materials and food products outside the EU market.

Agri-environmental regulations

Turning to the second arena of reregulation, the 1992 MacSharry reforms also recognised

the need to introduce programmes of environmental conservation into farming. For over

three decades evidence had been mounting of the environmentally damaging consequences

of productionist agriculture as regards habitat loss, resource depletion and pollution (soil

and water) and landscape degradation. The activities of environmental pressure groups,

together with the development of national agri-environmental programmes as in the UK

(Potter 1997), prompted action at the EU level. Under the heading of ‘accompanying

measures’ (Regulation 2078/92), member states were required to develop national agri-

environmental action policies (AEP) to encourage farmers to adopt environmentally sensitive

farming practices. Fifty per cent of the expenditure was to be provided from EAGGF, but at

a cost estimated at only 2 per cent of its budget.

However, the implementation of these agri-environmental policies in the UK should

be placed in the context of another political event, namely the 1992 ‘Earth Summit’ at

Rio de Janeiro and its resulting ‘Agenda 21’. Although the core concept of ‘sustainable

development’ has proved to be both contested and chaotic, and despite the absence of a

clearly defined programme of action, UK agriculture has been committed politically to

‘Agenda 21’ (Munton 1997). Nevertheless, ‘Agenda 21’ validates the reduction of farm

inputs (such as fertilisers and agri-chemicals), the production of environmental goods

(such as wetlands, moorlands and herb-rich pastures), and the protection of valued

landscapes.

Food quality and safety

The third arena of reregulation in agriculture concerns food quality and, more recently,

food safety; here the issues include animal welfare and how food is produced on the

farm (i.e. farming practice). Increasing numbers of consumers in the UK are prepared

to pay a premium price to assure the welfare conditions under which meat, eggs and

milk are produced, as well as guarantee chemical-free fruit, vegetables, meat and dairy

products. On the other hand, awareness of the health risks attached to food has increased.

Risk is now interpreted not only in terms of how different foods and qualities of food

impact indirectly on individual health (for example as regards heart disease and obesity),

but also directly in terms of salmonella poisoning, pesticide residues, E. coli infection

IAN BOWLER

88

and the potential link between bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in beef cows

and new variant Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (nvCJD) in humans. Thus consumers are

increasingly concerned with the origin of the food they eat, the farming practices by

which food is produced, the ‘freshness’ of food and the processing food is subjected to

after leaving the farm.

While the MacSharry reforms of 1992 recognised the issue of food quality

indirectly by identifying organic farming as a sector to be developed, more direct

recognition was given in 1992, under EU Regulations 2081/92 and 2082/92, which

provided protection to farm products characterised by particular modes of production

and regions of origin respectively. By 1997, for example, the following farm products

in the UK had been registered under the Regulations: Orkney Beef, Scotch Lamb, White

Stilton Cheese, Swaledale Cheese, Buxton Blue Cheese, Jersey Royal Potatoes,

Worcestershire Cider and Rutland Bitter. The development of high-quality, niche market

products is increasingly viewed as a way of combating a dependency on mass-produced

food products in increasingly competitive global markets, with regulations protecting

the premium prices available to the producers of such products. The development of

‘green’ consumerism underpins this arena of reregulation of agriculture, including the

market demand for farm products and food carrying an assurance of quality and safety.

Large food retailers have responded to the market opportunity offered by these consumer

concerns by establishing their own networks of farmers who are prepared to conform to

inspected standards and practices of crop and animal production. Such ‘assurance’

schemes are viewed as a marketing strategy at a time when new food health scares

appear with regularity.

The restructuring of UK agriculture

Regulation is but one of the processes bringing about agricultural change (Bowler 1996).

Other processes include agricultural technology, trade on national and international food

markets, the behaviour of non-farm capitals and consumer preferences. Given the confines

of space, this analysis now turns to the combined expression of these processes in empirical

measures of agricultural structures in the UK. Two groups of measures are identified: first,

features of productionist agriculture that are persisting from the second into the third food

regime; second, features that appear to presage the emergence of post-productionism in

agriculture.

The persistence of productionism

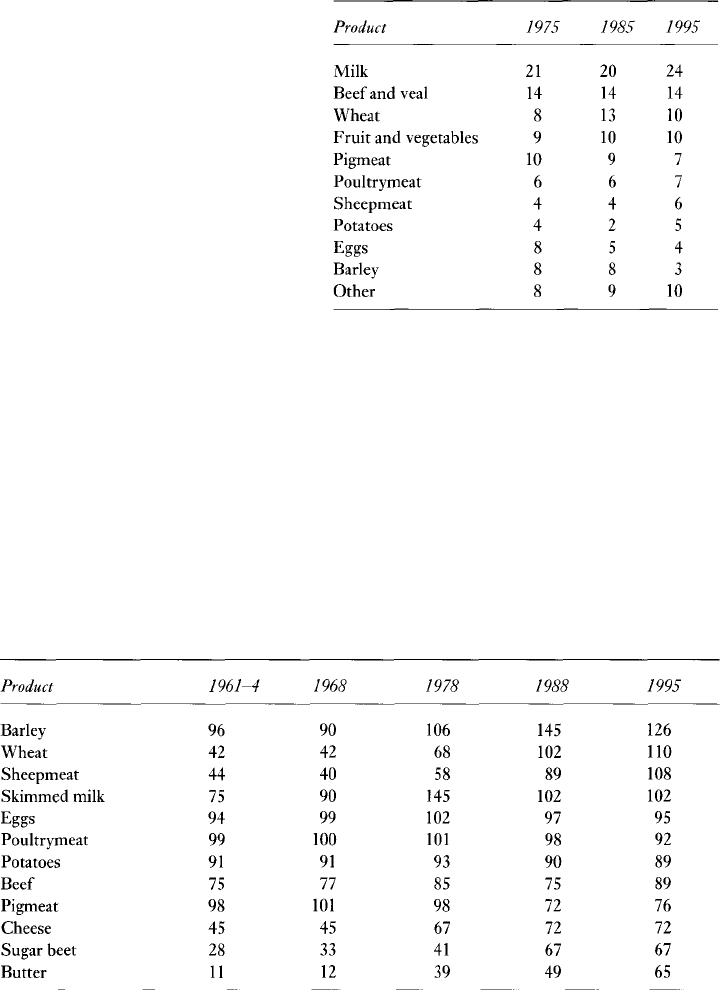

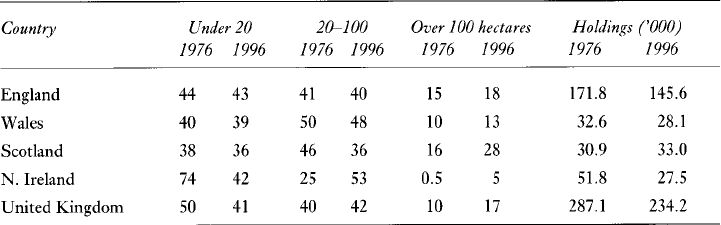

Tables 5.1 to 5.4 present a selection of indicators of national agricultural trends for the

transition between the second and third food regimes. The tables illustrate the continuity of

many productionist trends from the 1970s and 1980s into the 1990s. For example, Table 5.1

shows the broad structure of national farm output (by value) to be relatively stable between

1975 and 1995, with evidence of a gradual increase in the relative importance of milk,

poultrymeat, sheepmeat and potatoes at the expense of wheat, pigmeat, eggs and barley.

When measured in terms of national selfsufficiency (Table 5.2), most products have continued

with trends established during the second food regime. Increasing national self-sufficiency

is evident for wheat, sheepmeat, beef and butter, for example, whereas falling levels have

AGRICULTURE

89

continued for eggs, poultrymeat and

potatoes. Only barley and pigmeat

show changes in trend: self-sufficiency

in barley has fallen in line with its

reduced area under cultivation (see p.

96), while self-sufficiency in pigmeat

is rising after three decades of decline.

Overall, UK self-sufficiency in

temperate foods and animal feeds has

increased to approximately 73 per cent

and to 58 per cent for all food and feed

supplies. These national trends must be

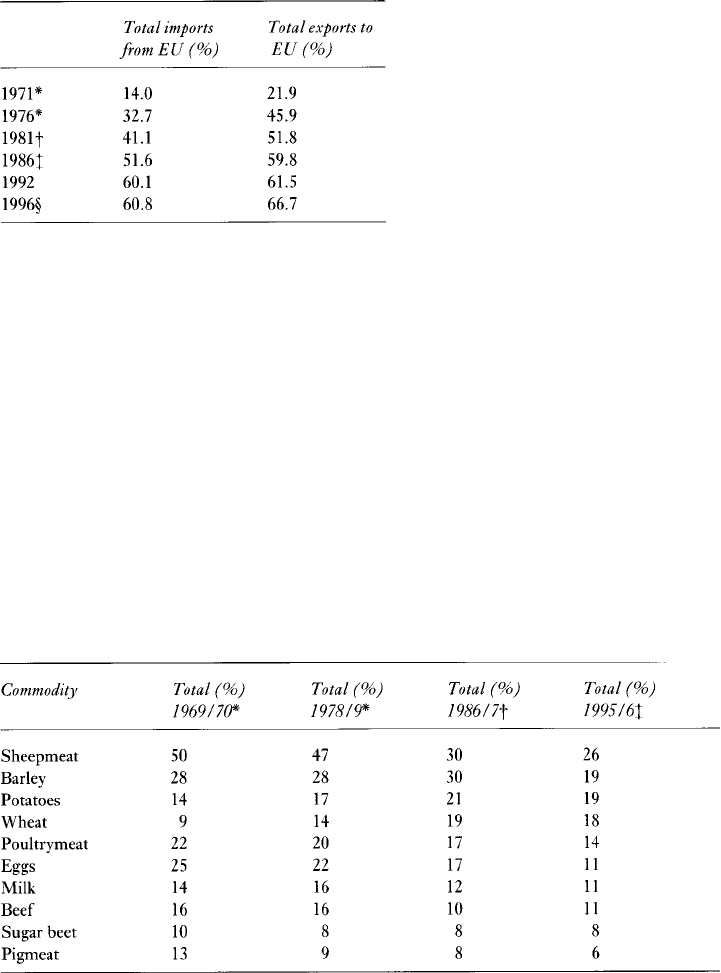

placed in the context of the UK’s

trading relationships with other

members of the EU. Table 5.3, for

example, shows how the growing

competition in the UK market for

agricultural products has come from

other member states, with national

agricultural imports reoriented from

non-EU to EU sources. On the other hand, two-thirds of UK agricultural exports are now

marketed within the EU. As membership of the EU has been enlarged, so the UK’s

contribution to EU production of most products has fallen (Table 5.4); but the country still

accounts for over a quarter of the EU’s production of sheepmeat and significant proportions

of the production of barley, potatoes and wheat.

TABLE 5.1 UK national farm output, 1975–95 (per

cent value of final production)

Source: Commission of the European Communities,

The Agricultural Situation in the Community—Report

(various years), Office for Official Publications of the

European Communities.

TABLE 5.2 UK self-sufficiency in agricultural production, 1961–95 (production as per cent total

new supply for use in United Kingdom)

Source: Commission of the European Communities, The Agricultural Situation in the Community—

Report (various years), Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

IAN BOWLER

90

The broad continuity of trends

within national agriculture reflects the

persistence of many productionist

processes into the post-productionist

period. These processes can be

summarised using the terms

‘intensification’, ‘concentration’ and

‘specialisation’ (Bowler 1996:4), each

dimension contributing to the uneven or

spatially differentiated development of

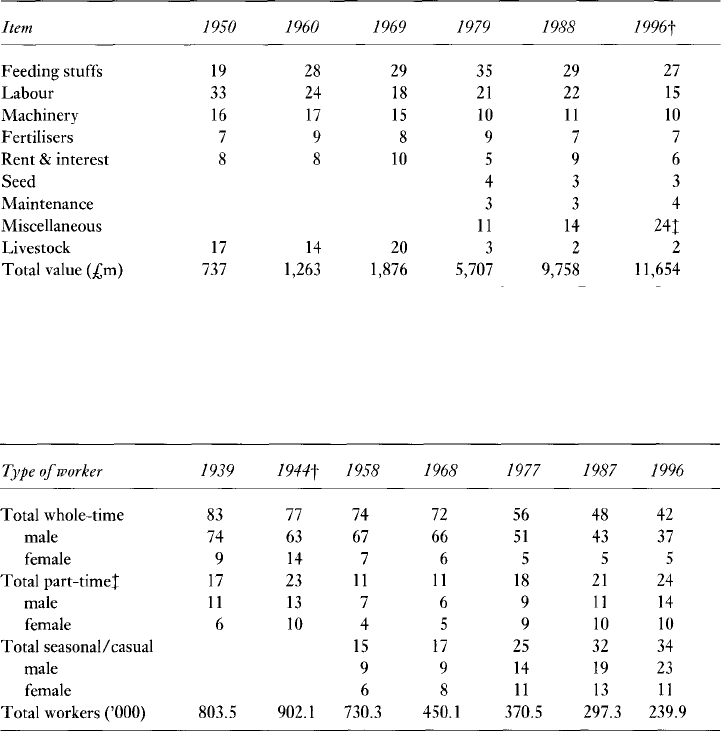

UK agriculture. Table 5.5 summarises

the intensification of farm inputs

(expenditure) between 1950 and 1996.

The capitalisation of agriculture

includes a continuing if declining

reliance on purchased livestock feed

(cheaper imports at the expense of

domestic production, especially barley)

and the gradual decline in expenditure on farm labour. Table 5.6 shows the changing structure

of the declining labour input in more detail. Capital continues to be used to purchase labour-

saving plant and machinery (10 per cent of national farm expenditure by 1996), allowing a

reduction in the total workforce from approximately 803,000 workers in 1939 to 240,000

by 1996. Within this total figure, lower-cost ‘intermittent’ or ‘flexible’ labour forms, such

as seasonal/casual workers, have increased to 34 per cent and part-time workers to 24 per

cent of the workforce. The main reduction has been in the number of more expensive whole-

time hired workers, especially males; by contrast, the number of family workers (i.e. farmers,

spouses, partners and directors) has fallen at a much lower rate and still provides about 63

TABLE 5.3 UK agricultural trade with members

of the EU, 1971–96

Source: Commission of the European Communities,

The Agricultural Situation in the Community—

Report (various years), Office for Official

Publications of the European Communities.

Notes: *EC6; †EC10; ‡EC12; §EU15.

TABLE 5.4 The UK’s changing share of EU output, 1969–95 (by volume)

Source: Commission of the European Communities, The Agricultural Situation in the Community—

Report (various years), Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Notes: *EC9; †EC10; ‡EU15.

AGRICULTURE

91

per cent of the total labour force. In addition agricultural contractors supply a wide range of

specialised machinery and labour for farming operations, ranging from ploughing, fertilising

and crop spraying to harvesting and land drainage. Just as farm labour inputs concerned

with animal feed have been replaced by non-farm workers in compound feed manufacturing

firms, so other labour inputs continue to be removed from the production sector and

substituted by off-farm specialised labour and capital.

Table 5.5 also indicates the fluctuating importance of interest payments over the last

three decades, set against a long-term decline in real value. Advances to agriculture by the

London Clearing Banks, for example, rose in just four years from £2,205 million to £4,234

TABLE 5.6 Workers employed on agricultural holdings in the UK, 1939–96 (per cent total workforce

in each year)*

Source: MAFF/SOAFD/DANI/WO, Digest of Agricultural Census Statistics (various years), HMSO.

Notes: *Excludes farmers, partners, directors and spouses but includes ‘regular’ family workers;

†Excludes Women’s Land Army and prisoners-of-war; ‡Part-time workers in Northern Ireland included

with casual workers.

TABLE 5.5 UK farm expenditure, 1950–96 (per cent total expenditure in each year)*

Source: Annual Review White Papers (1950–88), HMSO; MAFF/SOAFF/DANI/WO, Farm Incomes

in the UK (1996/7), HMSO.

Notes: *Rounding errors; †Forecast; ‡Of which pesticides 4%.

IAN BOWLER

92

million between 1980 and 1984, an increase of 7.2 per cent in real terms. The Agricultural

Mortgage Corporation, mainly concerned with loans for the purchase of farmland, also

increased its lending to farmers, from £393 million in 1974 to £945 million in 1985.

Indeed the value of farmland increased ahead of other assets with the flight of finance

capital into agricultural land under the 1973 oil-price crisis and the capitalisation of

increased CAP price supports into farmland values after the mid-1970s. Thus between

1970 and 1979, the farmland capital value index increased by 273 points, compared with

an equities price index gain of 73 points, and between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s the

average price of farmland with vacant possession in England rose from £1,643 to £3,789

per hectare. By 1988 UK farmers were paying £684 million in annual interest charges,

compared with £216 million in 1978.

The variability in farm indebtedness and farm incomes has been magnified in the

1990s both from year to year and between production sectors, but again set against the

background of a continuation of the long-term decline in the real value of farm incomes.

There have been a number of contributory factors, including falling real price levels under

the CAP; the opening of UK markets to greater competition; the devaluation and then

revaluation of sterling, leading to increased and then decreased EU farm support prices

within the UK; year-to-year variations in the level of payments under the Hill Livestock

Compensatory Allowance (HLCA); restructuring of the dairy processing sector; and the

banning of beef exports as a result of BSE in the national beef herd. Thus, aggregate net

farming incomes fell by 113 per cent in real terms between 1977 and 1987, bringing bank-

ruptcy to many individual farm businesses. But then average farm incomes rose by 65 per

cent in real terms between 1990 and 1995, after which falling trends were again experienced

under a period of revaluation after 1996. In the beef sector, for instance, production fell by

29 per cent between 1995 and 1996 under the BSE crisis, with beef farm incomes reduced

by 38 per cent.

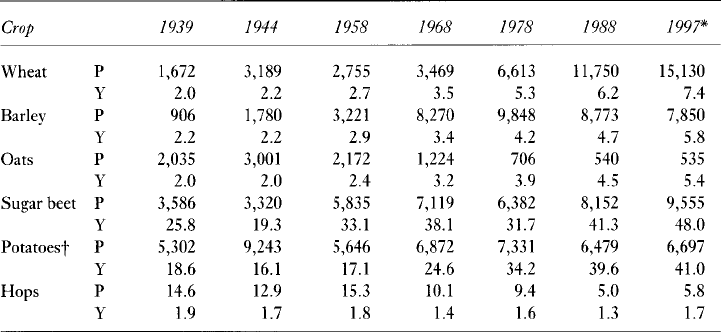

TABLE 5.7 UK production and yield of selected crops, 1939–97

Source: MAFF/SOAFD/DANI/WO, Digest of Agricultural Census Statistics (various years), HMSO.

Notes: P = production in ’000 tonnes; Y = yield in tonnes per hectare; *Forecast; †Maincrop.

AGRICULTURE

93

Turning to the intensification of farm output, crop and livestock yields have maintained

their upward trend. Table 5.7 shows the increasing yields of a selection of crops, supported

by more controlled applications of fertilisers (7 per cent of national farm expenditure in

1996: Table 5.5). Yields of wheat, for example, increased by over threefold between 1939

and 1997, while the yields of barley and oats more than doubled. Similar tendencies are

evident in yields from all classes of livestock. Taking an example from the dairy sector, the

average annual milk yield per dairy cow (recorded herds) in England and Wales increased

from 4,668 to 6,269 kilograms between 1975 and 1995; comparable figures for Northern

Ireland were 5,029 and 6,163 kilograms, with 4,602 and 6,354 kilograms for Scotland.

Looking now at concentration in UK agriculture, the development of fewer but larger

farm holdings has continued (Table 5.8), including the concentration of individual farm

products into fewer production units (Tables 5.9 and 5.10). It is worth noting that measuring

farm size structure is problematic, because the threshold size for holdings included in the

annual agricultural census has been revised upwards several times during the last forty

years (i.e. to exclude the smallest holdings). Taking the census statistics at face value, however,

the restructuring of agricultural holdings has continued, the total recorded number falling

from 303,600 to 145,600 in England between 1939 and 1996; comparable figures for Scotland

were 74,300 and 33,000, for Wales 58,000 and 28,100, and for Northern Ireland 88,900 and

27,500. Within these global figures, there is evidence of a greater rate of attrition amongst

smaller farms to the relative advantage of larger farms; that is to say, agricultural holdings

over 120 hectares in the context of the UK. However, there is little evidence of a ‘disappearing

middle’ of mid-sized family labour farms; indeed the main factor determining survival

amongst mid-sized and larger farms during the 1980s and 1990s appears to have been the

level of indebtedness of the farm business rather than its area size. Between 4 and 6 per cent

of farms change occupiers each year, with approximately 60 per cent of these businesses

falling vacant on the death or retirement from agriculture of the occupier. Between a third

and a half of farms changing hands are purchased by existing farmers or landowners with a

view to increasing the size of their farm business, thereby spreading production costs over

more units of output. Scotland appears to have experienced the greatest rate of increase in

the number of large farms, but the caveat regarding the changing basis of the agricultural

census remains.

TABLE 5.8 Farm-size structure of UK agriculture, 1976 and 1996 (per cent of holdings in each year)*

source: MAFF/SOAFD/DANI/WO, Digest of Agricultural Census Statistics (various years), HMSO.

Note: *Change in minimum size threshold of holdings enumerated in the census and differences in

threshold size between countries.

IAN BOWLER

94

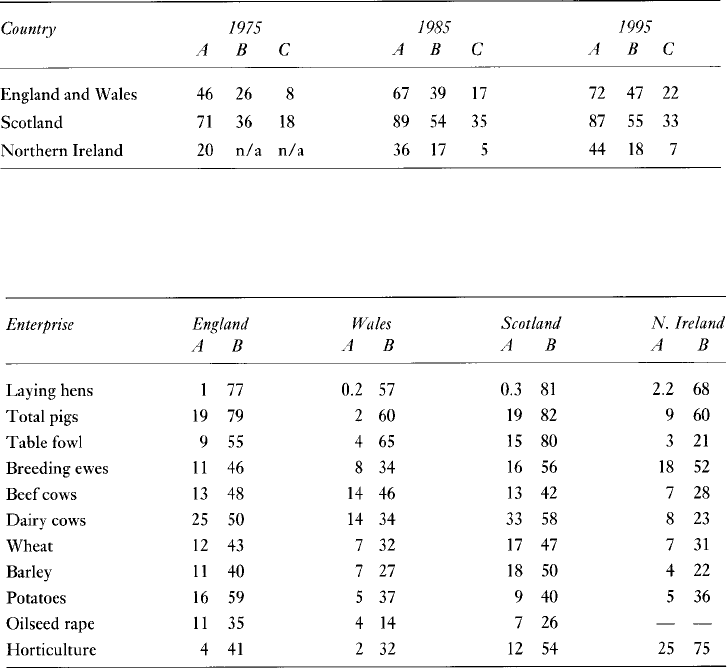

Enterprise structure is an alternative way of measuring concentration in agriculture.

During the second food regime, enterprise sizes were increased so as to gain economies

of scale—for instance, the area planted to potatoes on individual farms—and a small

number of larger farm enterprises increasingly accounted for a higher proportion of the

output of each product. Table 5.9 shows the situation for the dairy sector. In England and

Wales, in 1975, 8 per cent of farms with the largest herds (over 100 cows in milk) contained

26 per cent of all dairy cows; by 1985, 17 per cent of herds had over 100 cows, accounting

for 39 per cent of all dairy cows; while by 1995 the respective figures were 22 per cent

and 47 per cent. Indeed the process of enterprise concentration has continued into the

third food regime and Table 5.10 sets out the situation for a range of enterprises in 1996.

Intensive livestock (pigs and poultry) exhibit the greatest levels of concentration throughout

the UK: in England, for instance, the 1 per cent of largest enterprises account for 77 per

TABLE 5.9 Enterprise concentration in the dairy sector, 1975–95

Source: National Dairy Council, Dairy Facts and Figures 1996, NDC.

Notes: A = average number of cows per herd; B = proportion of cows in herds above 100 head;

C = proportion of herds over 100 head.

TABLE 5.10 Enterprise concentration in the UK, 1996

Source: MAFF/SOAFD/DANI/WO, Digest of Agricultural Census Statistics (various years), HMSO.

Notes: A = per cent largest producers (varying definitions); B = per cent area or livestock number

(varying definitions).

AGRICULTURE

95

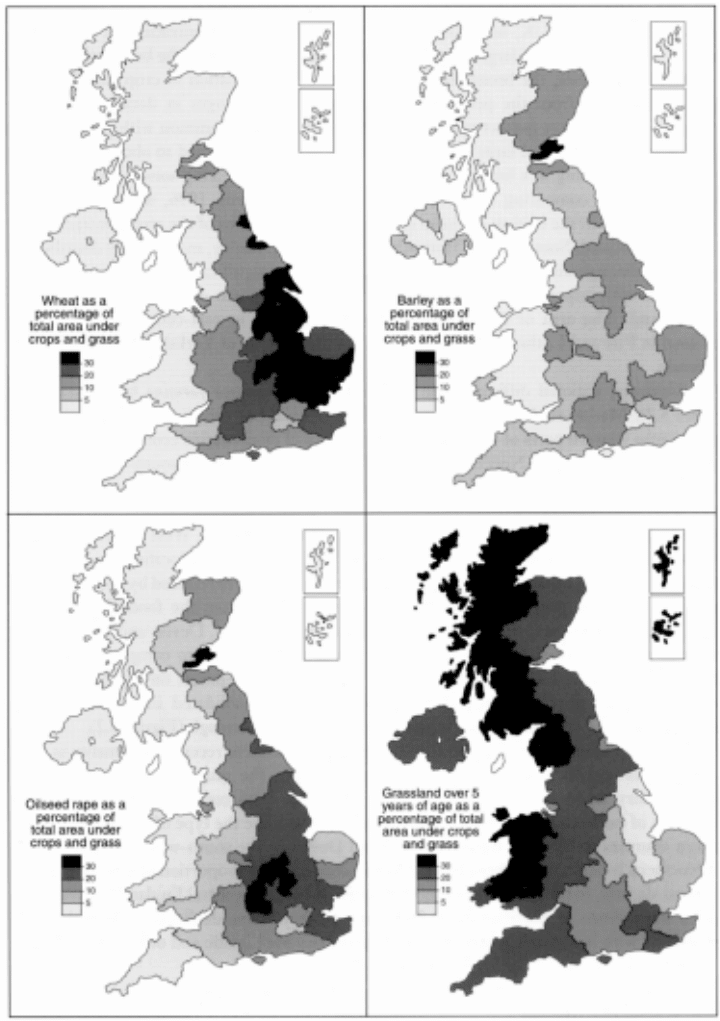

FIGURE 5.1 Regional distribution of selected crops, 1996

Sources: Agricultural Statistics, MAFF; SOAFD; DANI; WO.