Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

JOHN BLUNDEN

66

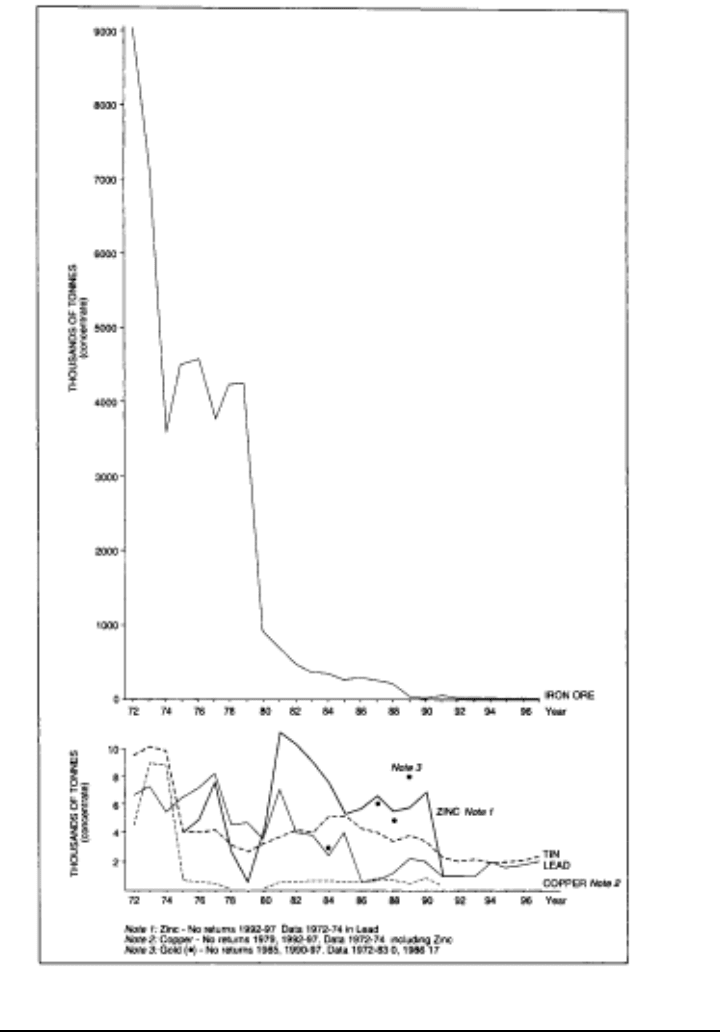

FIGURE 4.1c Metalliferous UK minerals: production levels, chief locations and utilisation, 1972–97

Source: British Geological Survey, United Kingdom Minerals Yearbook

EARTH RESOURCES

67

Iron ore

Used in steel manufacture, the primary outlets are the construction and transport industries. In 1966

nearly 14 million tonnes (metal content) were produced, but in that year the British Iron and Steel

Federation decided to withdraw from domestic supplies because of their low metal and high sulphur

content. The downturn in 1980 marks the closure of the main orefields of Northamptonshire. The

small quantities currently produced are from north Oxfordshire and Cumbria.

Lead

Used mainly in the manufacture of batteries, it is mined as a by-product of fluorspar. The reduction of

output over the period therefore parallels that of fluorspar. Small quantities of lead and zinc were

produced at the Parys Mountain mine in Anglesey in 1991, but a reappraisal of the site has given rise

to the expectation that production will soon recommence at a substantially greater level.

Zinc

Primarily used in galvanising, die-casting and as an alloy, it is worked only in association with lead.

Tin

It is mainly used as a coating for thin steel cans and in solder alloys, but also as an alloy with copper to

form bronze, and most recently in organo-tin compounds. Production reached its peak of 11,100 tonnes

(metal content) in 1871, a figure which was approached again only in 1973 (10,100 tonnes), at the

height of the revival of interest in tin mining in Cornwall. In 1993 output had dropped to 1,900 tonnes,

a figure from which it had barely recovered when production ceased in 1997.

Copper

Used mainly in electrical goods, its UK production is only very small and as a result of its presence

with other valuable ores. Production figures for most of the 1990s are not available. However, recent

exploration work at Parys Mountain in Anglesey suggests that this may become, within UK terms, a

significant source of copper, as well as lead and zinc. Gold and silver are also present in the deposit.

Gold

Mined only in North Wales in small amounts, output is confined to the jewellery market. Recent

production figures are not available but there is much exploratory activity involving both gold and

silver at Cononish near Tyndrum in the Scottish Highlands which is now well advanced, at Loch Tay

and Aberfeldy, in South Devon, in Co. Tyrone, and Parys Mountain, Anglesey.

circumstance of considerable overseas competitive advantage the very survival of tin

mining, let alone its revitalisation, would have to have depended ultimately on the

maintenance of buoyant world prices. But this was a situation which was to disappear

in 1986 when the Association of Tin Producers, which had largely been a controlling

agency with regard to price, was found to have built up over many years an untenably

high strategic stock, news which brought about a collapse in the world tin market

(Shrimpton 1987). This blow to high-cost operators such as those in Cornwall was one

from which they could not recover except with considerable state aid. Thus the 1990s

have witnessed the closure of Geevor, the cessation of underground working at Wheal

Jane with the withdrawal of its last government loan, and finally the one remaining

mine that had been in continuous production since the nineteenth century, South Crofty,

in February 1998.

JOHN BLUNDEN

68

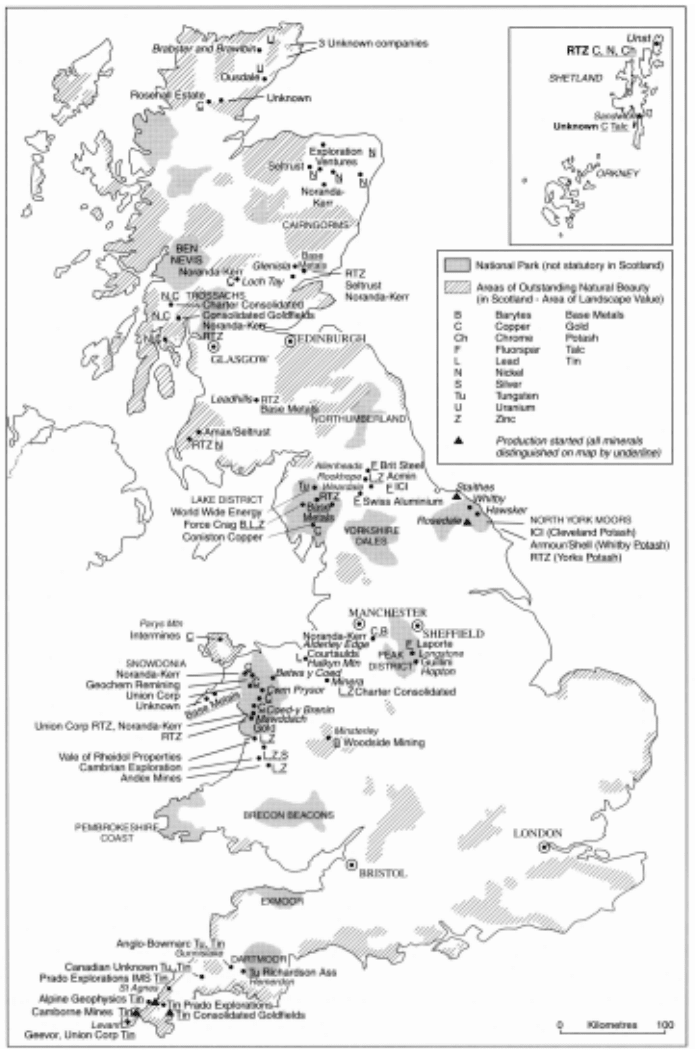

FIGURE 4.2 Minerals prospecting in Britain, 1972

Source: Blunden (1975).

EARTH RESOURCES

69

Minerals and the environment: the legislative framework

However, it was in the wider field of minerals development that another factor, that of

the environment, was to prove crucial in damping down much of the earlier optimism.

Given the densely populated nature of much of the UK and the smallness of its size, it

was recognised by government, even in the early 1970s, that expansion in minerals

output would have to meet the need for the highest possible environmental standards

and, as if to provide a counterbalance to its own new more permissive enabling

legislation, it set up three groups of experts to advise it in the 1970s: the Verney

Committee, whose remit was to investigate the supply of aggregates at minimum

economic and social cost but with the recognition that every effort would need to be

made to reduce environmental problems; the Stevens Committee on planning control

over mineral working including after-care and site restoration; and the Department of

the Environment’s (DoE) Mining Environmental Research Unit at Imperial College,

directed by the author, whose task it was to consider all the environmental aspects of

expanding indigenous minerals output, except those concerned with energy. All three

in the four years leading to the completion of their work took evidence from a wide

range of sources representing both industry and the conservation movement in the guise

of non-government organisations (NGOs), with the research group looking particularly

at other countries that had already experienced major mining operations, especially

those relating to industrial minerals. Both Stevens and Verney had the findings of their

respective committees published in 1976, whilst the work of the research group was

completed with its series of private reports to the DoE in the same year.

Their success in effecting change was partial but none the less meaningful and

was incorporated in the Town and Country Planning (Minerals) Act, 1981. This achieved

a significant extension of the Mineral Workings Act, 1951, with respect to post-

operational site requirements, since it included what is termed ‘after-care’ whereby

minerals companies sustain an ongoing management regime, normally to be for five

years after minerals extraction had ceased, rather than a once and for all rehabilitation

programme which could easily be cosmetic. Indeed, the regime imposed might also

require of the mining company that the land be made suitable for agriculture, forestry,

or amenity. The Act also determined that county planning authorities should be the

minerals planning authority with a duty to make regular reviews of areas which have

been, are being or are to be used for mineral working. Following a review, the authority

could revoke or modify a planning permission or prevent further working of the land

(Roberts and Shaw 1982).

Mining and sensitive environments

However, it may be seen in retrospect that the Act has not worked as well as it might have

done with regard to curtailing damage to especially sensitive environments which can

result from the process of mining or quarrying itself, and with respect to the disposal of

wastes where these can become a significant factor of land-use and amenity adjacent to

workings. This has been particularly so in the case of National Parks where old consents

to work minerals often exist which pre-date the 1951 Minerals Working Act. The

Environmental Protection Act, which became law in 1990, however, allowed planning

JOHN BLUNDEN

70

authorities to review such workings with a view to either modifying the consent or

permitting its continuation as before. Few planning authorities used this power until the

Peak Park Joint Planning Authority was faced in the mid-1990s with a situation posed by

Ready Mix Concrete (RMC) which might have inflicted severe damage on the landscape

at Longstone Edge. At their recently acquired quarry at this location, the company

attempted to extract limestone in a situation where the consent had specified that fluorspar

and barytes might be worked along with other minerals, but made no specific reference to

limestone. RMC’s plan to remove 15 ha to a depth of 60 m would not only have produced

19 million tonnes of limestone, but have severely impaired the appearance of the skyline

to the extent that the planning authority decided that it would use its powers to revoke the

original consent. The company at first stated that it would appeal against the decision, but

it has now agreed not to contest it, and showing great pragmatism perhaps in the light of

its wider interests as a leading aggregate producer, expressed its keenness to work with

the Peak Park. Apart from the decision being welcomed by environmental NGOs, the

action taken by the planning authority is being seen as a test case by other National Parks

in England and Wales which currently face more than a hundred similar ambiguous

quarrying consents (Jury 1998; Bent 1998).

This particular problem apart, the extraction of limestone for chemical or aggregate

purposes from its ten active quarries has been a major source of conflict in an area which is

supposed to be devoted to conservation and recreation. However, the largest of these,

Tunstead, near Buxton, which was formerly outside the boundaries of the Park, has been

allowed a major extension into it. The approval of this development was given on appeal

because the national need for high purity limestone for chemical use was considered as

more important than its environmental impact and the designation of the area as a national

park. The quarry came into production in the mid-1980s and over its predicted life of sixty

years it is likely to have an average output of 10 million tonnes per year of chemical limestone,

together with some aggregate material.

As for fluorspar, of which the UK is an exporter, 70 per cent is won within the

boundaries of the Peak Park. When the market was at its most buoyant in the late 1970s

and early 1980s, this mineral, along with barytes, was extracted at a number of sites

some of which were open pit operations rather than underground workings. This in

itself caused widespread damage to the visual qualities of the landscape, as did the

disposal of waste from its primary processing (about 3 tonnes to every one of valuable

material). This was largely accomplished through the provision of tailings ponds where

the wastes, suspended in water as a result of processing, settle out. Even though these

may be ultimately drained and grassed over, they remain an alien feature in the landscape.

However, the environmental situation has recently improved. There are now fewer open

pit operations, with a greater concentration on underground working and with minerals

processing limited to one plant. Moreover, the backfilling of waste, combined with

cement, into the worked-out areas has reduced the need for tailings ponds but not

eliminated them. The only way in which this might be achieved would be to use the

remaining wastes for the manufacture of aggregate materials. Unfortunately, these would

still be produced in quantities well in excess of the needs of local markets (Peak Park

Joint Planning Board 1998).

EARTH RESOURCES

71

Waste materials: the case of china clay

Of the remaining highly localised non-metalliferous minerals extracted in the UK, all have

some interface with the environment even if, like salt and potash, they are worked

underground and have a minimal waste problem. However, in terms of the scale of waste

production and its visual impact, by far and away the most impressive of UK minerals is

china clay (kaolin). This, above other industrial minerals, is the nation’s chief export in

terms of both tonnes extracted and value, with 80 per cent of output going overseas. For all

these reasons it demands special attention here. China clay is removed from roughly circular

pits the largest of which can be around 100 ha, or about twenty times the size of Wembley

football stadium. These are frequently around 60 m deep, and roughly two-thirds the width

of the grassed area of the same arena. Of the material extracted seven out of every eight

tonnes are quartz waste, which is piled up in immense white tips. In addition there are also

extensive ponds in which the very fine micaceous waste materials from processing are

placed to de-water now that these are no longer discharged into local rivers. Not surprisingly,

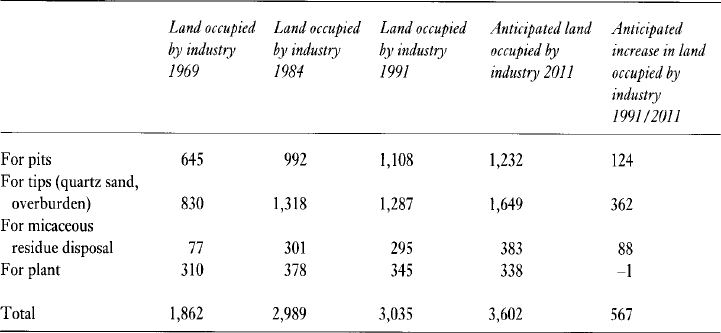

the land requirements for the industry in the area are of gigantic proportions, as Table 4.1

demonstrates (Blunden 1996a).

Given high levels of production over many years and the concentration of the main

Cornish workings in the St Austell area they represent a major visual intrusion in a rural

landscape otherwise largely exploited by agriculture and tourism. Travellers approaching

the area from the north-east along the A30 road can catch their first glimpse of the waste

TABLE 4.1 Land requirement (in hectares) for the china clay industry in the St Austell area

Source: ECC International.

Note: The problems of waste disposal for the china clay industry are particularly problematic. The

fourfold increase in land used for the dumping of micaceous residues between 1969 and 1984

reflects the phasing out of marine disposal in favour of tailings ponds. In the years since 1977 when

a reclamation scheme was instituted, 348 ha of the land taken for tipping and 80 ha of that given to

tailings have been reclaimed, mainly for amenity purposes. Open pits remained unreclaimed until

recently but now 162 ha have been back-filled with waste materials from processing. In the period

1995 to 2011, 34 per cent of tip requirements will come from backfilling. The relatively static

requirements for plant over a period of increasing product output are an indicator of improved

processing efficiency.

JOHN BLUNDEN

72

tips, sometimes referred to as the ‘Cornish Alps’, at least 12 km away. The same is true of

the only other important clay workings which abut the Dartmoor National Park in Devon.

The waste tips at this location can be seen from Plymouth 16 km away, as well as from a

number of tors (rocky hills) inside the south-western boundary of the Park.

Since the St Austell china clay workings represent the only major industrial

development in Cornwall, with all that follows from that in terms of employment, the planning

authority has granted it a special status in order to secure its long-term interests in land-use

terms. But whilst the operating company’s consents for working are long standing and

largely pre-date planning legislation, the planning authority has negotiated the closing down

of many small clay pits in the county in order to concentrate environmental intrusion and

damage into the one area. Moreover, it has accepted English China Clays’ desire not to

sterilise its pits by back-filling with waste since none of them has yet been bottomed, but

has otherwise negotiated with the company a long-term programme of waste revegetation

and general landscaping work. However, its other site at Lee Moor on the edge of Dartmoor

has long been a contested area. Although the exhaustion of the working can be foreseen in

the twenty-first century and for which rehabilitation schemes have been agreed with the

planning authority, the Dartmoor Preservation Society has vigorously resisted all applications

for additional land for waste tipping for the reasons of visual impact on the boundary of the

National Park described above.

Aggregates: some problematic issues

In the case of non-internationally traded aggregate minerals, it is the environmental factor

that has also proved particularly problematic. In the first place the appetite for sand and

gravel has been particularly voracious (see Figure 4.3). Moreover, sources of sand and

gravel are usually synonymous with areas that are sensitive to such extractive activities;

for example they are likely to have to be developed close to urban areas, or on high-

quality grade 1 agricultural land. In London’s Green Belt alone in excess of 3,300 ha

have been actively worked, with more than another 3,000 ha approved by planning

authorities for the same purpose. Nuisance caused by the unsightly appearance of such

workings, and by dust and noise at them, together with increased traffic moving to and

from these sites, is often the source of considerable dissatisfaction amongst the general

public. Sand and gravel extraction is therefore increasingly opposed whenever a planning

application is made.

But since such workings often take place at or below the water table, as they are most

frequently located in valley floors, their eventual rehabilitation can usually be readily

achieved. Processing plant can easily be removed and any waste sand or gravel poses no

threat to the environment since it can readily be landscaped by using earth-moving equipment

and is often graded so that it slopes gently to a central lake. In the UK the best-known

examples are along the River Thames, both in its lower reaches west of London and near its

headwaters on the Wiltshire/Gloucestershire border; near Olney in Buckinghamshire; and

at Holme Pierrepoint in Nottinghamshire. Most of these areas have been reclaimed as

recreational facilities in the form of water parks catering primarily for water sports such as

sailing, water skiing and fishing. Nevertheless, the demand for such facilities is far from

inexhaustible and other forms of reclamation have been tried. Some planning authorities

have thought them to be appropriate as landfill sites for domestic, ndustrial and other wastes.

EARTH RESOURCES

73

Several hundred hectares of wet sand and gravel pits have been filled in the Greater London

area where the demand for land for development has been strong. However, where these

wet sites are concerned, the main type of material used is rubble or inert waste, for in spite

of encouraging research into disposing of domestic refuse into wet pits, no satisfactory

economic method of eliminating the risk of polluting groundwater supplies has been found

(Blunden 1996a).

Such a generally less than encouraging situation, together with a falling supply of

sites that are likely to prove unproblematic, has tended to direct the pressure for aggregate

elswhere, especially sources of hard rock generally to be found in upland areas. This has led

to greatly increased quarrying activities in places such as the Mendip region of Somerset,

the Craven district of North Yorkshire, the Brecon Beacons of South Wales and the Charnwood

Forest district of Leicestershire, all of which supply centres of consumption in the south-

east of England. But these are valued for their landscape qualities, with many of them

designated as National Parks or Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (see Chapter 20).

Open pit operations of the sort required here (or for that matter for the extraction of metallic

ores and clays) give rise to many of the same problems as lowland sand and gravel workings.

They may also require the removal of considerable volumes of rock overburden in the

course of their development, and, since they are generally distant from major population

centres, refilling quarried-out areas with suitable urban waste when working ceases may

not be economically feasible. Thus in spite of efforts to restore voids to their original surface

levels, this remains the exception rather than the rule. In the UK, of the annual take of land

for limestone, only 5 per cent is completely restored. In such situations attempts at

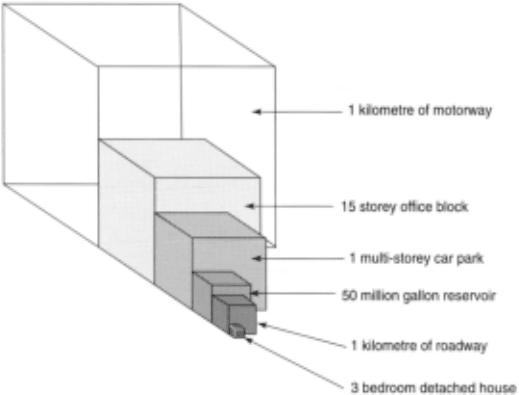

FIGURE 4.3 Aggregates and construction

Aggregates are the cheapest of all minerals to exploit and vast quantities are used in

construction work. On average 50 tonnes are needed for a three-bedroom house and

62,500 tonnes for every kilometre of a six-lane motorway.

Source: Blunden (1996b:160).

JOHN BLUNDEN

74

rehabilitation are confined to trying to mellow as rapidly as possible the disused vertical

working bluffs. Here the natural or artificial regeneration of flora can be assisted by creating

screes at their bases and by layering their faces with ledges on which plant life can take hold

(Clouston 1993). Apart from the presumption that the primary purpose of National Parks is

conservation and the encouragement of recreation, quarries may still continue to damage

the landscape since, as already noted, some of these pre-date the designation of those parks.

Indeed, in exceptional cases consents are still given in such areas, in spite of fierce resistance

from the many conservation NGOs, such as the Council for the Protection of Rural England

(CPRE), Council for the Protection of Rural Wales (CPRW), and the Council for National

Parks.

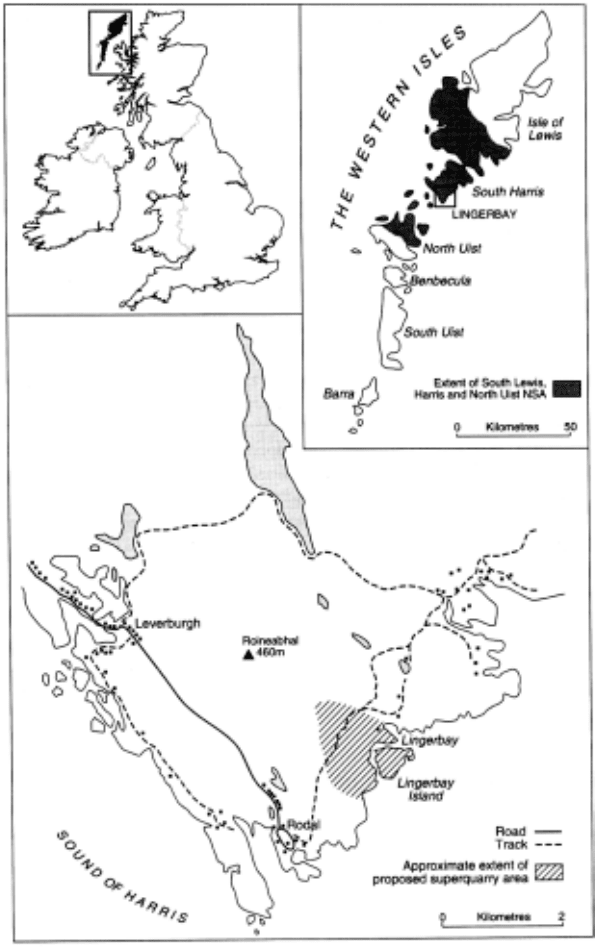

It was the Mining Environmental Research Unit at Imperial College that in the

mid-1970s recognised these difficulties and suggested that one solution might be found

in the development of remote coastally located aggregate superquarries in Scotland

(Figure 4.4). Through the use of inexpensive sea transport to the major market of south-

eastern England, these might economically subsume the role of many smaller traditional

local operations and assume a lower environmental profile. Only very recently has

government come to support this notion actively, acknowledging that, given its demand-

led policies for aggregates, if it allows rising output to be met in such a way it might be

less exposed in terms of public concern. However, it is an approach that has come

under attack because it cannot be consistent with the government’s acceptance of the

principles of sustainable development laid down at UNCED in Rio in 1992, which

demands alternative approaches that embrace aggregate conservation and recycling

(CPRE 1996).

Minerals and sustainable development

Definitions of sustainability are, of course, arguable. Some suggest that it must preclude

any form of growth. Others have put forward a rather more pragmatic approach. English

Nature, for example, has sought to express its own view of sustainability in looking ‘to

establish limits of human impacts based on carrying capacity…promote demand

management so as to keep development within carrying capacity’, and ‘oppose

development and land use which adversely and irrevocably affects critical natural capital’

(1993). Such a view, if not precisely the same in every particular, has been generally

shared by other statutory agencies such as the Countryside Commission (1993), NGOs

such as the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (1993), as well as the House of

Lords Select Committee on Sustainable Development. Differences of opinion, where they

do exist, are to be found amongst the environmental organisations, where some feel that

the concept of development within environmental capacities might be interpreted as a

presumption in favour of development up to capacity in all areas. This might threaten

some of the wildest and most unspoilt places. Others have reservations about the utility of

the concept of ‘critical environmental capacity’, fearing that even if intentions are good it

could undermine existing designations.

However, the question arises as to how far the Department of the Environment (DoE,

now DETR) has managed to accept at least a mediated definition of sustainable development?

Certainly, since the Verney and Stevens Reports of 1976 it has accepted that the adverse

impacts of minerals extraction should be minimised and in its Minerals Planning Guidance

EARTH RESOURCES

75

FIGURE 4.4 The Lingerbay superquarry proposal, South Harris. One of a number of proposals from

minerals companies for a superquarry. Such an operation must have aggregate reserves in excess of

150 million tonnes and an annual output greater than 5 million tonnes, which is mostly exported by

sea. This proposal came from Redland Aggregates Limited

Source: CPRE (1996).