FTA (изд-во). Flexography: Principles And Practices. Vol.1-6

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

separator and photographer. Most digital

camera software offers the option to convert

from RGB to CMYK on the fly, but unless the

photographer is a trained separator, the

CMYK conversion should not be done. The

separator has the print characterization data

and experience and should do the conver-

sion. However, the photographer does need

to control and properly set the following:

• Make certain that the highlight and

shadow input/output values are set to

the tonal range of the actual flexo

curve. Setting tonal values in this way

limits the amount of detail and con-

trast in the photo. The full 0–256 gray

scale range should be used. By using

software like Adobe PhotoShop, the

flexo tonal range can then be applied

to the photo data file.

• Ensure that the lighting and exposure

of the actual photo area is controlled

so there is plenty of detail in the shad-

ow areas.

• Be sure the camera is capturing true

neutrals. A gray reference should be

used in each photo. Camera software

should be properly neutralized to the

gray reference.

Halftone Images

Halftone, process, grayscale, monotone

and continuous-tone images all refer to art-

work that has been scanned or created in a

pixel-based application such as Adobe

PhotoShop (Figure

3$

). Working with such

images opens an entirely different arena of

situations that need consideration during the

design process.

Content of image. Applications such as Adobe

Illustrator, Macromedia’s FreeHand or

QuarkXpress allow a designer to crop,

rotate, resize and mask graphics, but it is far

better to manipulate raster images directly

in PhotoShop.

Unfortunately, many artists do not use

PhotoShop to perform these tasks. If an

image is cropped or masked in PhotoShop

before it is placed in an illustration program,

the image file is easier to manage in the sec-

ondary application. Modifications in Photo-

Shop also make the overall size of the com-

pleted artwork file smaller, which then

makes transfer easier across a network or

process through a prepress system or RIP.

Screen resolution. It is important to use the

specified line screen resolution when view-

ing illustrations for approval. Viewing at the

correct line screen can be done with the

color printer, but cannot be seen on the mon-

itor. Line screens can look very different at a

high resolution, such as 175 line screen, com-

pared to low resolution (45 line screen).

Typically, color proofs and monitors use a

viewing resolution comparable to a 175 line

screen.

Color. Another area of consideration is the

color mode of the image that the designer is

working on. If a full-color photograph has

been scanned in, chances are that the photo-

graph was scanned into RGB channels.

Initially, when working during the design

phase of the artwork, using RGB channels

can be helpful in expediting the creative

process. Files saved with three channels

makes for a smaller file, which allows for

faster manipulation of the image in desktop

application programs. A problem occurs

DESIGN 37

3$

Halftone, process,

grayscale, monotone

and continuous tone

images all refer to

artwork that has been

scanned or created in a

pixel-based application.

3$

38 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

when the designer does not preview the

image in CMYK. The file should be sent to

the separator in the original RGB format.

The separator will then convert to CMYK

using the correct dot-gain compensation.

RGB channels are a color mode used for pro-

jecting color onto the monitor. It is also the

color mode that many desktop scanners sup-

port. But presses do not print in RGB and if

a press will not support a color mode,

chances are excellent that a prepress system

or RIP will not support it either. Some pre-

press systems will not process an artwork

file if an RGB image is detected. Converting

files into printable color modes is done very

simply inside an application such as Adobe

PhotoShop. It can be very useful for the

designer to know what file formats and color

modes are supported by the prepress system

or RIP that will process the artwork files.

Trap. Trapping a halftone to another halftone

can be tricky because different halftones

contain common colors. The designer may

not want a trap to occur, while the prepress

software may automatically apply a trap. It is

best to consult with the prepress provider to

find out what will happen when these files

are sent to the RIP. It is up to the designer

and separator to decide whether or not the

halftones should be trapped to each other.

Trapping a halftone to a solid color or out-

line is fairly simple. If the halftone is trap-

ping to a dark color, the trap probably will

not show. But if part of the halftone is dark

and part light, a dark line color will show in

the light area of the halftone.

Shadow, Highlight. Shadow and highlight

areas (the darkest and lightest areas of an

image) can have a positive or negative impact

on the overall design appearance, depending

on these areas print. When an image has a

highlight area that graduates from 15% black

to 0%, it may look good on the computer

screen and may even print out beautifully on

the laser proof. There is no guarantee, how-

ever, that what is seen prior to printing is

what is going to come off the press. To avoid

this type of problem, a designer should be

aware that all presses are different and refer

to the specific press characterization data

from the printer or separator.

Each press has a set of tolerances or lim-

its. For example, some presses are unable to

print very small dots. These limits occur for

a variety of reasons. T he substrate that a job

is being printed on, the plate material or the

ink being used can cause limitations. Even

the pressman running the press can have an

effect on the print appearance of a particular

project. Looking back to the example of a

graduated highlight area consisting of 15%

black through 0%, imagine that the press

running this particular project is unable to

print any dots that are 5% or lower. The

result will be graduated areas of the image

that fall within the 0% to 5% range will not be

printed. When this occurs in a highlight area,

what will appear on the printed copy is a

gradual reduction of the black area and then

an abrupt stop at 5%. This abrupt stop leaves

what is known as a “break”, or if we com-

pare it to printing with a rubber stamp, a

bald spot where the ink didn’t print.

A designer can modify the highlight areas

so this “break” will not occur if he/she

knows which press the project will run on.

Using the example of a highlight area that

graduates from 15% to 0% with a break at the

5% area, a designer can modify the highlight

area so that it graduates from 15% to 6%. This

modified gradient will provide enough dot

coverage to prevent a break or bald spot

from occurring.

A similar phenomenon can occur at the

opposite end of the tonal range. Shadow

areas in an image may “close up”, become

“muddy” or “disappear”. The primary cause

of shadow areas “closing up” is a problem

known as dot gain. Dot gain on a press is cre-

ated when the surface of the plate (which is

loaded with ink) comes into contact with the

substrate and impresses (prints) the image

onto the substrate. A variety of reasons may

cause the image to become slightly enlarged.

When an area of the artwork is tinted or

screened, the dots that create this screen

can become enlarged during the printing

process (Figure

3%

).

There are ways of applying creative solu-

tions to manipulate halftones and accentu-

ate the look of the graphics while hiding pos-

sible print defects. In Figure

3^

, the black in

the text is the same process black that is in

the image of the apple. Many times black

requires more impression or a higher vol-

ume anilox to get good, solid coverage. This

approach, however, will make the process

black in the apple print heavier and there-

fore, they will look dirty. If there are enough

print units, the black in the text can print on

a separate unit from the one used for the

black in the halftone image. Impression on

the black in the apples can remain light, giv-

ing it a crisp, clean look.

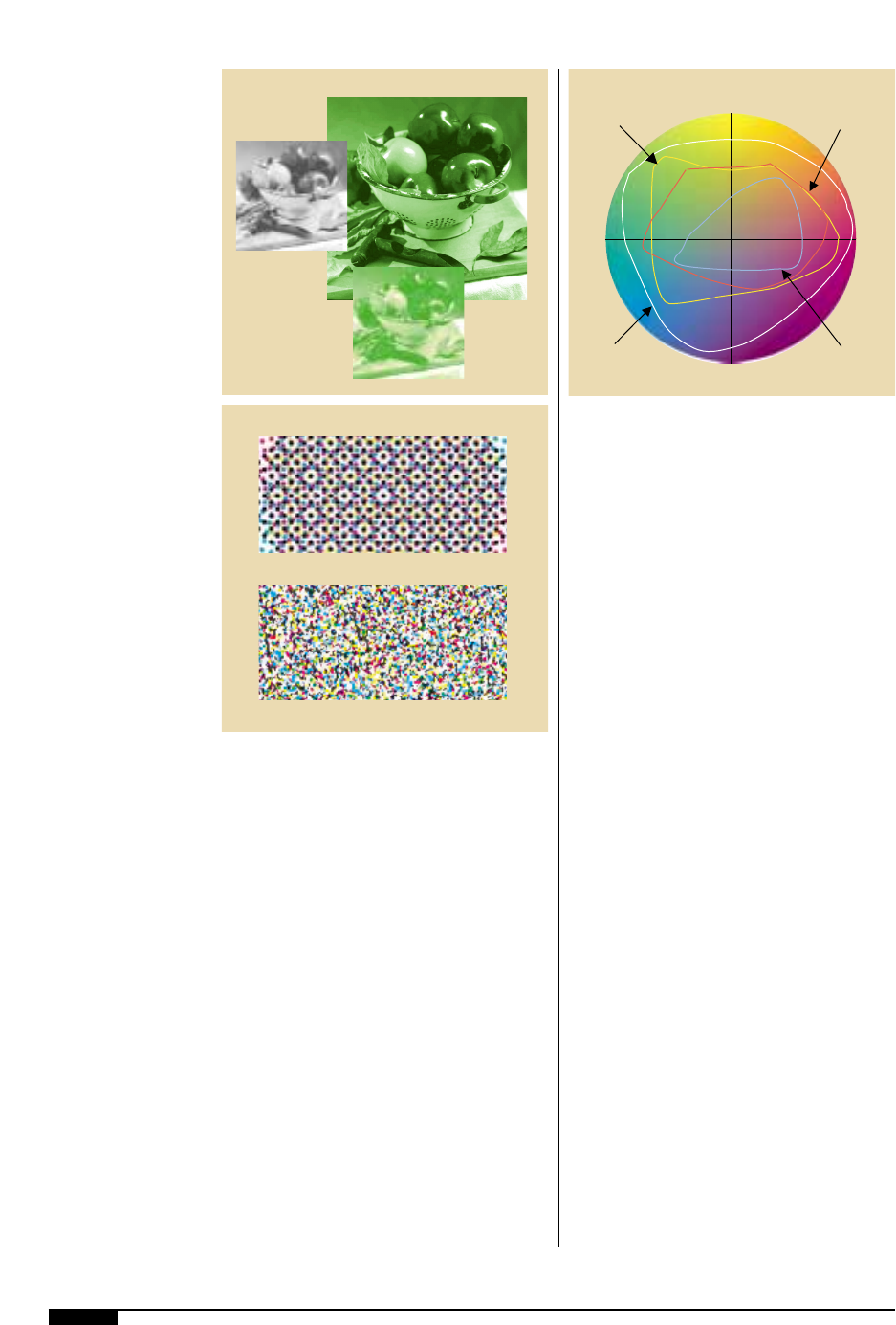

Duotones

A duotone is a halftone consisting of two

colors (Figure

3&

). One color is usually used

for the highlight and shadow areas and the

other color for the midtone areas. Not only

do duotones offer a fresh look for conven-

tional halftones, they also offer print advan-

tages over some halftones. Duotones can be

used for particular print situations. For

example, when the registration tolerances

are not very tight a halftone made up of four

colors instead of two could look quiet blurry.

Duotones can also be used just for the inter-

esting graphic effect of a two-color halftone.

Duotones are handled by both the designer

and separator the same way halftones are

handled, except for color breaks. It is impor-

tant to proof a duotone so everyone can see

and approve or reject the two-color look.

The settings and color separations need to

be adjusted and proofed until a desirable

outcome is achieved. Duotones can be fun to

work with and look better than halftones in

many cases.

Alternative Screens

Traditional halftone screening uses the size

of the dot to convey shading. The larger the

dot the darker the shading, while smaller dots

provides lighter shades. Alternative screens

can be visually appealing options for the

designer. These screens look different than

conventional halftone screens and can be

more forgiving to print than conventional

screens. Alternative screens come in the form

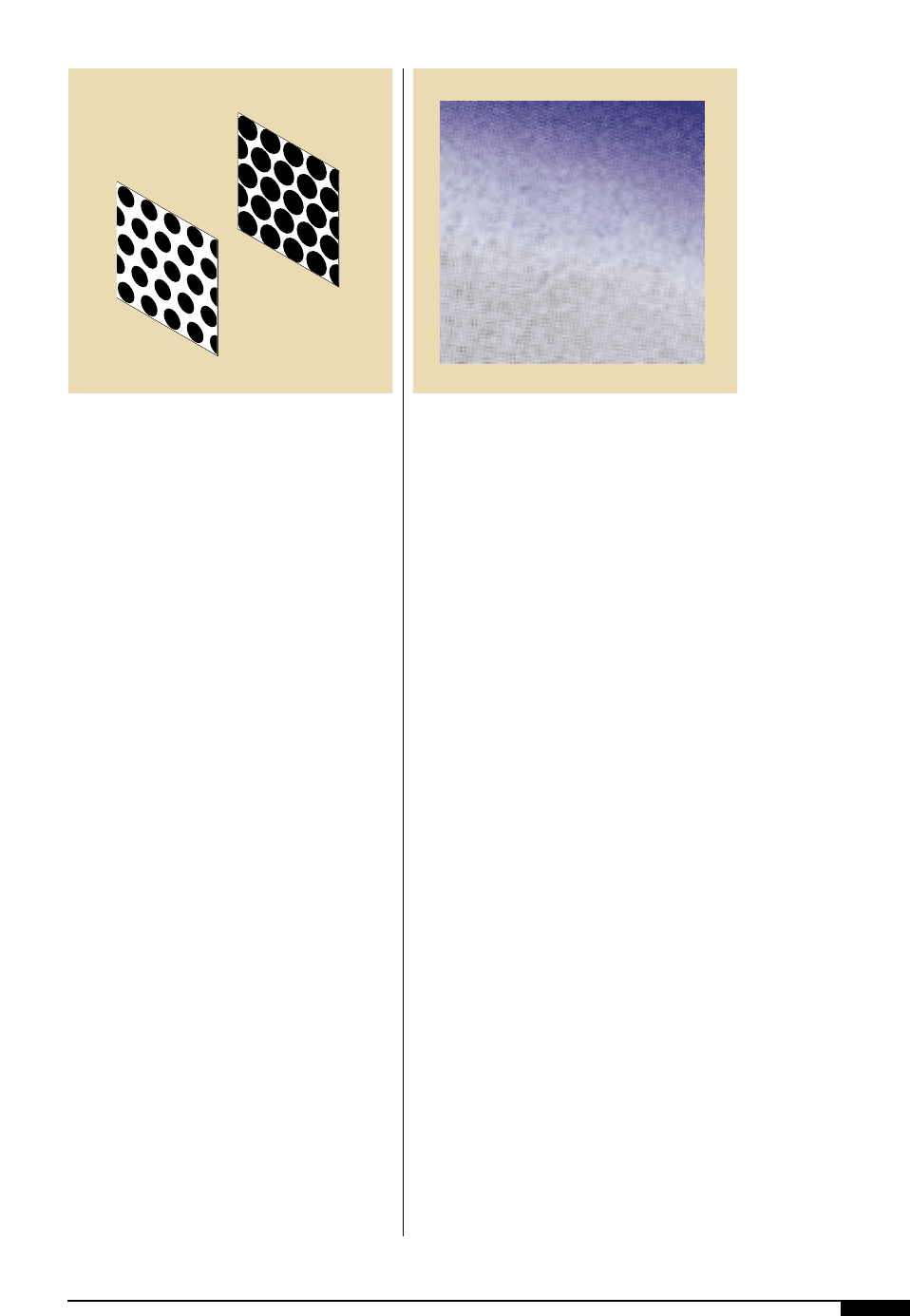

of mezzotints, random or FM (Figure

3*

),

pixelization, noise and others. Much atten-

tion has been given to FM (Frequency

Modulated), also known as stochastic,

DESIGN 39

3%

Halftone dots typically

increase in size as the

wet ink spreads when it

reaches the surface of

the substrate.

3^

To achieve good solid

coverage on the solid

black, without causing

the process black to

fill in, two black print

stations are used.

Film Negative

Halftone Dot

Printed

Halftone Dot

3% 3^

40 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

screens in the past few years, although

usage in final production is still limited. FM

screening renders the different shades of an

image by controlling the number of dots in

each area. More dots produce darker areas

and fewer dots produce lighter areas. FM

and conventional screening can be com-

bined effectively in what is called combina-

tion screening, which is covered in more

detail in the prepress chapter.

Before using any screen other than a con-

ventional screen, the separator and printer

should be consulted. The characterization

data for new screen styles is not the same as

that for conventional screens. Dark print or

low contrast images could result if the new

screen is not characterized on press before

being used in a design. These screens could

have very small dots – smaller than 1% con-

ventional dots, which might not print or be

on the plate at all. There could be RIP prob-

lems as well, because the RIP may not cor-

rectly interpret the data. Once the character-

ization and RIP tests are successfully com-

pleted, alternative screens can be handled in

the same manner as conventional screens.

High-fidelity Color Printing

High-fidelity color printing uses additional

process inks in order to reproduce more of

the color spectrum. A package printed with

high-fidelity color may use orange and green

inks in addition to the cyan, magenta, yellow

and black process inks. This would increase

the color gamut by approximately 20%

(Figure

3(

). High-fidelity color is relatively

new and is not widely used at this time, but

produces some very striking results.

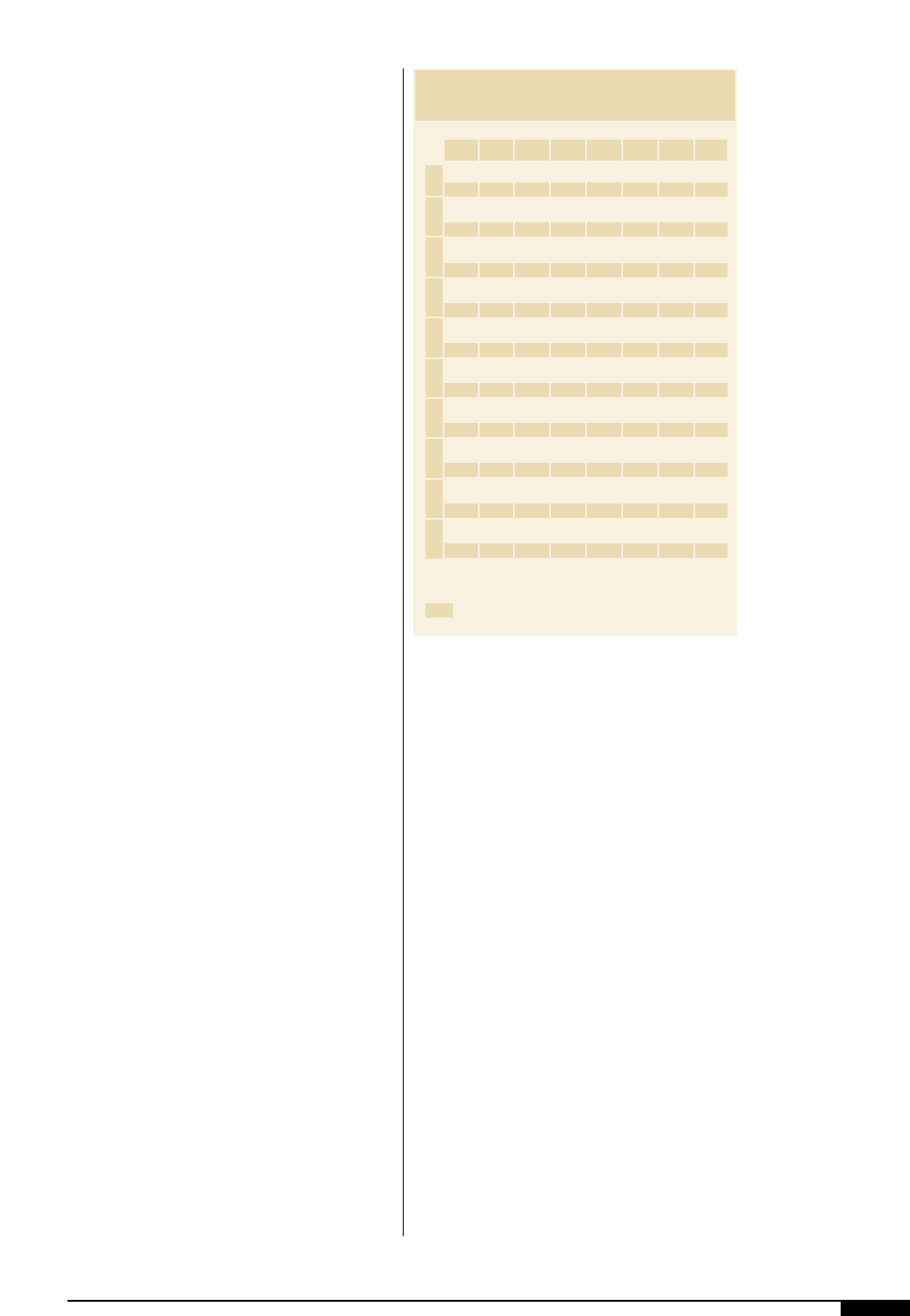

Scanning

The rule of thumb for scanning in pho-

tographs is to scan an image at a resolution

that is double the line screen used to print

the image. Hence, an image that is to be

printed at a 100 line screen should be

scanned in at 200 dpi (dots per inch). If an

image is scanned at too low a resolution,

there is little that can be done to improve the

quality of the image for printing. If any devi-

3&

Duotones are usually

printed in black and a

custom color. In an

image-processing pro-

gram it is very easy to

see how a duotone will

look on-screen before

the image is finalized.

3*

Conventional (AM) and

FM Screening. Because

there is no regular dot

pattern in FM screening,

moiré patterns cannot

occur and the smaller

dots display more

detail.

3(

The color gamut shows

the enlarged palette of

colors available with

high-fidelity printing

techniques.

RGB

Color Gamut

Pantone

Color Gamut

Visible

Color Gamut

High-fidelity

Color Gamut

3(

3*

3&

ation from the rule of thumb is made, it is

better to scan an image at a higher resolu-

tion than is needed. Reducing a file’s resolu-

tion is a much more pardonable offense than

trying to add resolution to an already

scanned image (Table 6).

The image should not be scanned using

offset settings. The settings must be adjusted

for flexo. The information needed to scan

includes the minimum highlight, maximum

shadow and the dot-gain curve. The dot-gain

curve can be used as the density curve. The

scanner operator will convert this dot gain

curve into the correct density curve. GCR

and UCR are widely used in flexo printing

and the scanner operator can adjust the scan

for the correct amount of each of these vari-

ables if this information is provided. GCR

and UCR are applications used to make the

black longer in the shadow areas. In other

words, instead of trying to create shadows

or neutrals with a combination of C, M and

Y, black is used. Using these applications

makes register, color control and trapping

much simplier during the printing process.

Since more black is being printed, the print-

er will separate the process black and the

line black onto different print decks. This

separation allows the printer to set the press

for enough density and coverage to print bar

codes and fine type, but limit dot gain in the

process image.

The artist should also consider the size at

which the image is to be scanned. If any

enlargements to the original image are to

occur, it is best to scan the image at the

enlarged size. The scaling of images can

have a direct impact on the time it takes to

process the completed artwork. Also, the

scanned image should not be much larger

than the size at which it will be printed. A

label image might be scanned from an 8" x

10" transparency, creating a 21.6 mb file. Yet

the label might only print at 2" x 2.5", which

is only a 1.35 mb file. When the image is

scanned in at a much larger size, the design-

er or separator will have to reduce this

image to the print size to make the file small

enough so that it is manageable. If the orien-

tation of the print is known, it should be

scanned at the same orientation, if possible.

Correct orientation saves output time and

also makes the files somewhat smaller.

Bar Codes

Almost all packages require either a bar

code or UPC symbol for pricing, identifica-

tion and inventory information. FIRST

(Flexographic Image Reproduction Stan-

dards and Tolerances) and ANSI (American

National Standards Institute) have specifica-

tions that should be followed. The difficulty

for a designer who has to use the UPC code in

a package design is that the specifications for

creating these symbols are very strict and

UPC codes rarely, if ever, add to the appeal of

an overall design. Not only have bar codes

DESIGN 41

Table 6

2700 Digital file size image scanned at 266 ppi/133 lpi

3430

Digital file size image scanned at 300 ppi/150 lpi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

12345678

FILE SIZES OF SCANNED IMAGES

277 553 830 1080 1350 1620 1890 2160

352 704 1030 1370 1720 2060 2400 2750

553 1080 1620 2160 2700 3240 3780 4320

704 1370 2060 2750 3430 4120 4810 5490

830 1620 2430 3420 4050 4860 5670 6480

1030 2060 3090 4120 5150 6180 7210 8240

1080 2160 3240 4320 5400 6840 7560 8640

1370 2750 4120 5490 6870 8240 9610 11000

1350 2700 4050 5400 6750 8100 9450 10800

1720 3430 5150 6870 8580 10300 12000 13700

1620 3240 4860 6480 8100 9720 11300 13000

2060 4120 6180 8240 10300 12400 14400 16500

1890 3780 5670 7560 9450 11300 13200 15100

2400 4810 7210 9610 12000 14400 16800 19200

2160 4320 6480 8640 10800 1300 15100 17300

2750 5490 8240 11000 13700 16500 19200 22000

2430 4860 7290 9720 12200 14600 17000 19400

3090 6180 8270 12400 15500 18500 21600 24700

2700 5400 8100 10800 13500 16200 18900 21600

3430 6870 10300 13700 17200 20600 24000 27500

42 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

become a necessary evil, they also have a

very strict set of tolerances that must be fol-

lowed by the designer and separator.

If designers decide to generate the bar

code themselves, there are many utilities and

applications available in the desktop envi-

ronment that will create bar codes and UPC

symbols. A word of caution: if a designer

chooses to generate the bar codes to be used

in the final printed piece, then he/she also

accepts all of the legal responsibility for guar-

anteeing that the bar code will print accu-

rately. Should the designer decide that this is

a responsibility he/she does not wish to

incur, he/she can provide an FPO. The FPO

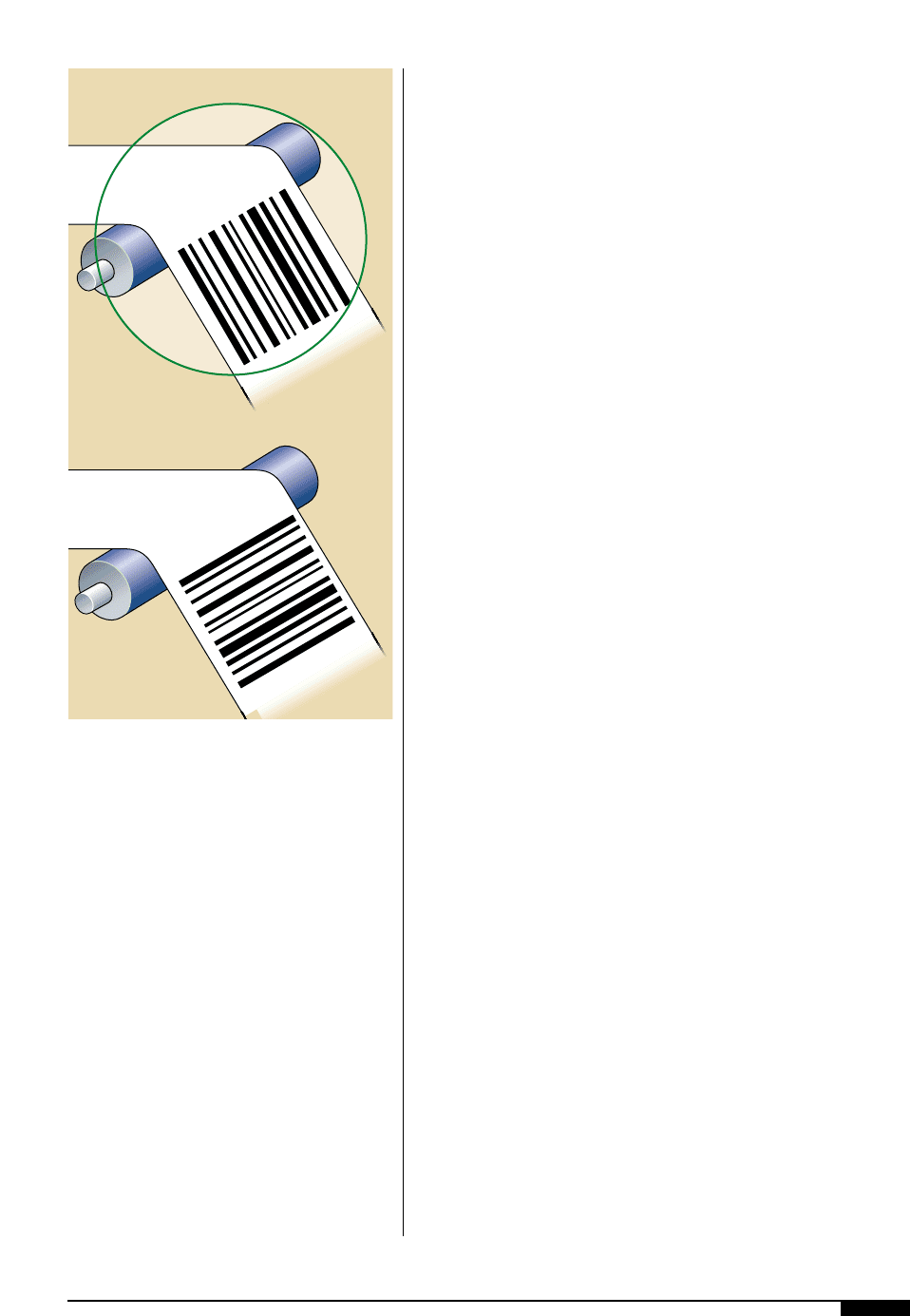

(Figure

4)

) represents where the bar code is

to be placed in the design and the separator

creates a correct, final bar code. When pro-

viding an FPO for the final placement of a bar

code, the designer should be aware of the tol-

erances necessary for accurately printing a

bar code, so that the placement, dimensions,

quiet zone and color of the FPO are correct

for the final printed symbol. The ultimate

goal by everyone involved is to create a sym-

bol that, when scanned, is within ANSI stan-

dards of acceptance.

Compensation. Compensation is achieved by

undercutting the bar width, so that when

printed with the expected amount of gain,

the bar code grows back to the original size.

Color and Symbol Contrast. When selecting a

color for the UPC symbol or bar code, it is

imperative to choose a color combination

that will provide sufficient contrast between

the scan bars and spaces. Black bars with

white spaces provide the highest symbol con-

trast (SC) for accurate scan reading. The

amount of required SC varies based on the

symbol and where it will be used. The light

sources used in bar code scanners generally

use red light. Therefore bar codes should not

be colored in reds or oranges, as they will not

read when scanned. These colors can be used

for background colors. If the bars are printed

with a color other than black, dark colors

such as brown, blue and green; with back-

grounds in yellow, orange, pink, peach and

red generally scan successfully. Bar codes

should be created with one color to create

sharp edges and avoid any register issues.

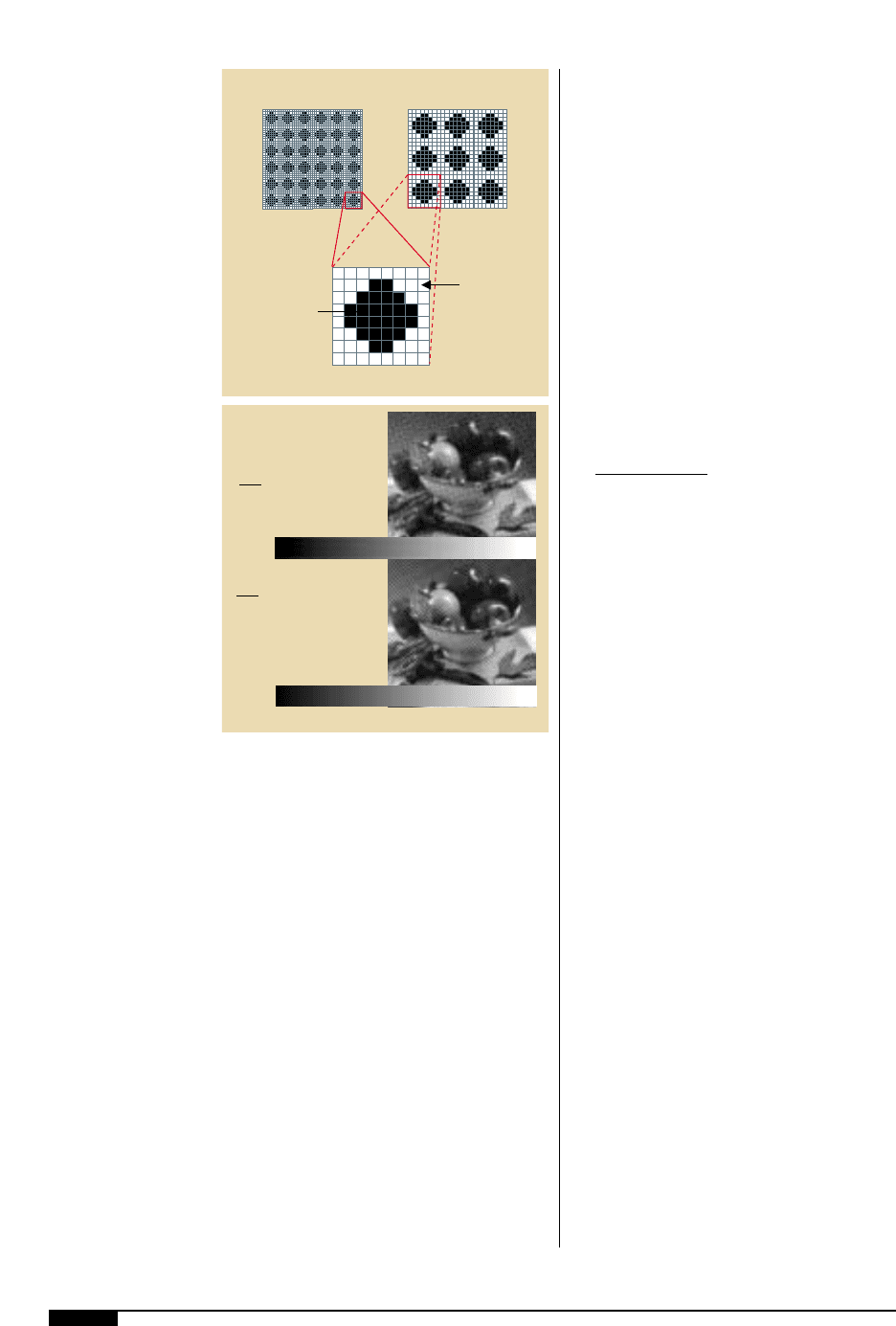

Placement. Certain types of packaging may

require specific symbol placement. The posi-

tioning depends on the symbol used and the

packaging of the product. It is strongly rec-

ommended that the symbols be printed in

the web direction, also known as through the

press or picket fence (Figure

4!

). The

widths of each bar and background space

are what the scanner detects and must be

printed as accurately as possible. When the

symbol prints through the press, the bars

might be longer because of press slur, but

the width will not be affected. If there is no

other choice but to print in the across the

press direction (Ladder) the printer must

provide specifications.

Size. Symbol sizes are specified according to

the symbol and the use. UPC codes that are

scanned by point-of-sale scanners have a

fixed relationship between height and width.

The specified magnification range is 80 -

200% of nominal size. Most symbols have

minimum requirements for the quiet zone,

the background area free of printing on the

left and right side of the bars. As symbols are

reduced in size, so are the bars and back-

4)

An FPO label denotes

that the bar code shown

is only intended to indi-

cate orientation, size,

color, etc.; it is not to be

printed.

4)

ground areas. Tighter tolerances are

required for bar-width reduction. Most sym-

bols have a height/width relationship that

must be maintained, which makes trunca-

tion unacceptable.

Color Reproduction

and Line Count

When continuous-tone, full-color repro-

duction from original copy is required – as

with color photographs and transparencies,

oil paintings, reflective art, watercolors and

illustrations – a full understanding of three-

and four-color process printing is mandatory

If single-color reproduction of continuous-

tone copy is required – as with photographs

or vignettes – halftone reproduction must be

fully understood and an appropriate halftone

screen count specified. The original artwork

must be digitally captured to be usable in the

computer by using a flatbed or drum scanner

or a digital camera.

For printing either tints or halftones on

corrugated board, 45- to 65-line screens are

suitable. Screens for wide-web package

printing on film range anywhere from 65- to

133-line, while narrow-web printers typically

range from 120 to 150. 200-line screen print-

ing and higher is being achieved with the use

of newer technology in plates and anilox

rolls. The preprinted linerboard industry ini-

tially attempted 150-line screens, but

dropped back to 100- to 133-line screens

with far better results.

When halftones, duotones, three- and

four-color process halftones are used in a

design, they can either be handled separately

in photography, photoengraving and printing

or they can be combined with line work. The

method depends on the number of printing

stations available, whether line copy is fine

enough to print on the plate with halftones,

or whether the presence of large solids in the

line plate makes it preferable to run the

halftones separately. Running halftones sepa-

rately minimizes ink distribution problems

and allows finer impression control.

Many times, a low-resolution file is placed

in position by the designer as a FPO. It is the

separator’s job to replace FPOs with high-

resolution images. All FPOs must be clearly

marked.

Screen Ruling. When referring to illustra-

tions, halftones, screen tints and duotones,

screen ruling refers to the number of rows or

lines of dots used to render an image. Screen

ruling is measured in lines per inch (lpi). The

relationship between the output resolution

(dpi) and the screen ruling (lpi) determines

how fine or coarse an image will appear in

print. To determine screen ruling, fill a 1"

square area with an imaginary grid that con-

tains 100 lines running vertically. Next fill

the square with 100 imaginary horizontal

DESIGN 43

4!

Bar code symbols

should be printed in the

web direction, also

known as through the

press or picket fence.

When the symbol prints

through the press, the

bars might be longer

because of press slur,

but the width will not be

affected.

Picket Fence

Ladder

4!

44 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

lines. The intersection of each line has a dot

on it; the number of lines of dots in this

arrangement is referred to as the line screen.

In this example, the line screen is 100 lpi. If

the square has 133 lines vertically and hori-

zontally, it is 133 lpi.

Screen ruling also determines the size of a

halftone cell, which in turn determines the

maximum size of a halftone dot. The rela-

tionship between screen ruling and printer

resolution determines the tonal range that

can be printed. The halftone dot is made up

of printer dots, with the printer resolution

determining the number of dots available to

create the halftone dot. When the screen rul-

ing is increased, the size of the halftone cell

is decreased and fewer printer dots are used

to create the halftone dot, so fewer shades

are represented (Figure

4@

).

Printable Line Screen (lpi). Line screen print-

ability varies greatly depending on the print

variables. These variables could be sub-

strate, ink-metering system, ink formulation

and anilox configuration. The same graphic

can look very different depending on the

particular line screen (Figure

4#

) used, and

successful designs must look good in the

line screen actually printed. Line screens

can vary from 45 to 175 lpi.

To calculate the levels of gray available at

a given screen ruling and output device, use

the following formula:

output resolution

2

1 shades of gray

screen ruling

The maximum number of grays available

on most output devices is 256. The levels of

gray available also determine the smooth-

ness of blends and vignettes.

Blends, Vignettes and Gradation Fills.

Vignettes, gradients and blends all describe a

color filling in an area of artwork where one

or more colors progress from one percentage

of the color or colors to a different percent-

age. When used correctly, gradients can add

spectacular results to a design. When created

incorrectly, they can be extremely difficult to

print accurately or can ruin the overall

impact of the final printed piece. The tools

available in desktop software applications

make it very easy to add gradients to every

element of a design. Unfortunately, it is also

easy to create them incorrectly. Because gra-

dations can be complicated, it is recom-

mended that the designer create the grada-

tions as an FPO with the design specifica-

tions noted, and let the separator create the

final, ready-for-film gradation. When working

with blends and vignettes, the following

characteristics of the gradations should be

considered: tonal range, banding, and color

mixtures.

Tonal range. Most artists will create a tonal

4@

The lower the screen

ruling, the larger the

halftone cells; the high-

er the screen ruling, the

smaller the halftone

cells.

4#

Increasing the line

screen ruling creates

smaller halftone dots

which adds detail to the

image, but it reduces

the number of grays

available.

Low dpiHigh dpi

Halftone Cell

Halftone Dot

Printer Dot

(dpi)

4@

1

257

levels of gray

2400

150

2

1

1,112

levels of gray

2400

72

2

4#

range of 0% to 100% for all gradients or

blends. This range presents problems in

flexo. Because some flexo plates cannot hold

a dot below 3%, the tonal range in the graph-

ics should typically not be below 3%. Some

plates can hold a 2% or even 1% dot, but

because of substrates, anilox or ink choices,

the dot is often not printed. Therefore, when

creating the flexo gradient, the minimum dot

percent should be what is specified in the

characterization data. On the shadow end,

dot percentages above 85% have a tendency

to “fill in” which can result in an excessive

ink laydown. Again the maximum shadow

dot should be in the characterization data

(Figure

4$

). If this data is not available, use

the standard flexo gradient of 5% to 85% .

Banding. A problem that can occur when

using a gradient fill is banding (Figure

4%

).

When tints do not blend smoothly, there is a

distinct “stepped” appearance as opposed to

a nice, smooth gradation of tints blending

from one percentage to another. Banding in

a gradient is usually created when the length

of the area to be filled exceeds the capabili-

ty of the number of gray levels available for

a particular gradient range to fill the area.

Banding can be avoided by remembering a

few, basic rules:

1. Keep gradient fills small. Banding is

more likely to occur in gradients that

cover a large area.

2 Use larger gradient ranges. A blend

from 5% through 25% covering a rela-

tively large area will most likely band

because there will most likely not be

enough gray levels to create a smooth

transition from tint value to tint value.

A larger range, such as 5% through 75%

will be more successful.

Another way to create gradients is to man-

ually create a blend by selecting two ele-

ments in a file and using the blend tool in the

application’s toolbox. When creating gradi-

ent blends in this manner, the operator has

the ability to set the number of steps that

will complete the blend. If gradients are cre-

ated in this manner, 256 steps should be used

DESIGN 45

4$

Tonal range in the press

characterization.

4%

Banding in a vignette

occurs when the length

of the area to be filled

exceeds the capability

of the number of tint

levels available.

3373839404142

024686 88 90 92 94 96 98 100 024686 88 90 92 94 96 98 100

4$

No Banding Banding

4%

46 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

to create a blend that varies from 1% to 100%.

A gradient that blends from 1% through 50%

requires a minimum of 128 steps to blend

without banding. Simply put, more steps

equal better blends.

Another cause of banding in vignettes

occurs when blends run at a variety of differ-

ent angles on a design. Electronic artwork

files must be converted to binary coding

when set to the RIP to be output on a film

imagesetter or platesetter. Binary coding uses

a coordinate system that is comparable to a

grid. Under the line screen grid is a secondary

grid that is determined by the resolution of

the artwork file. The line screen grid can be

rotated on top of the underlying resolution

grid. Because the line-screen grid can be

rotated, but the resolution grid (which con-

tains the dots) cannot, banding can occur

when lines in the line-screen grid run in dif-

ferent directions than those on the resolution

grid. This phenomenon can be compared to

painting a wooden fence. The paint lies more

evenly and fills in all of the cracks with a

stroke that follows the grain of the wood, ver-

sus a stroke that runs across the wood. Paint

strokes that run cross-grain can leave cracks

that are completely untouched by the paint.

A good way to avoid banding in a vignette

is to create the gradient in Adobe PhotoShop

and use the “Add Noise” filter. The “Add

Noise” filter will shift the pixels in the gradi-

ent blend so that different tint values will not

align along a straight edge. This shift creates

a feathered effect that softens any hard

breaks where different tint values meet. The

difficulty in using this method to create

vignettes is that files generated from Adobe

PhotoShop are much larger than files creat-

ed in Adobe Illustrator or Macromedia’s

FreeHand. The PhotoShop files must be

placed in a drawing application and can be

difficult to manipulate inside the drawing

program. These files can also greatly

increase the amount of disk space the art-

work file requires for storage.

Blends which might appear banded on the

computer screen, or even on a laser proof,

may have been correctly created and may

not band in the final film. Computer screens

generally display at a resolution of 72 dpi.

The artwork will probably be output to film

at a resolution of 1,200 dpi, or even higher.

These higher resolutions of film imageset-

ters will help in decreasing the possibility of

banding in a gradient fill.

Color Mixtures. When two elements are made

of two different spot colors and then blend-

ed manually, the resultant blend might not

actually consist of the two spot colors.

Usually drawing programs will convert this

type of blend automatically into a process-

color breakdown. The blend function is

unable to separate the different percentages

of both spot colors and hold the integrity of

those colors at all tint values. It is easier for

the application to convert the entire blend to

process colors. For example, if a blend

needs to be created with a blue-spot gradient

to a red-spot gradient, the designer will have

to create two separate gradient blends. The

blue should be placed on top of the red, with

the blue gradient set to overprint. This pro-

cedure is the only way to ensure the gradient

will separate into the two spot colors upon

film output. It is also important to consult

the separator or printer because some col-

ors, yellow or beige for example, can grade

to 2% but look like a fade to 0%.

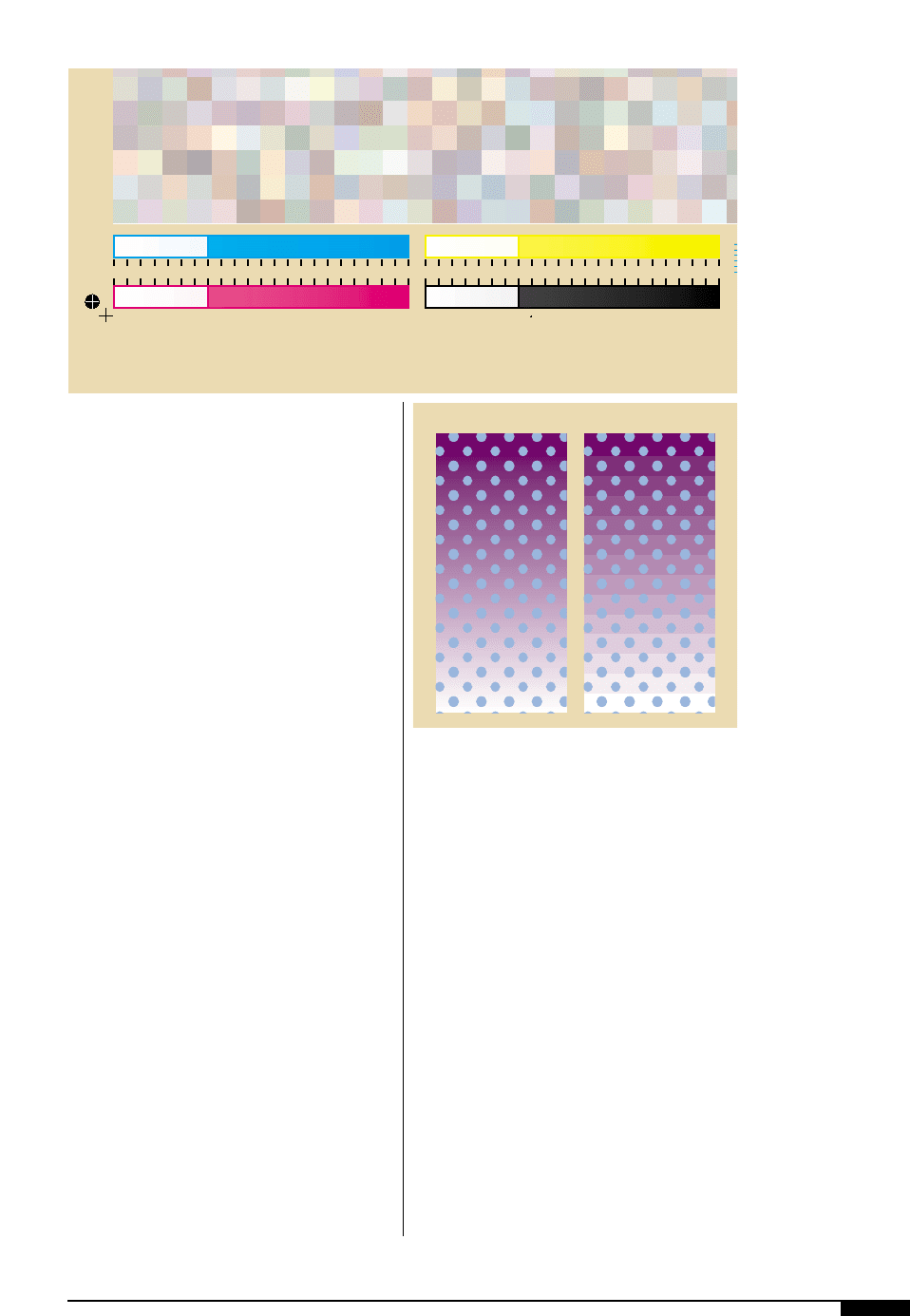

Color

Creating a custom color palette before

beginning the actual design is a good practice

for designers. At this time, they should refer

to the print color criteria of the project. The

print color refers to how many and what col-

ors will be printed. The designer should not

use colors that the printer will not be using.

Usually the palette includes cyan, magenta

,yellow, black and any spot or special colors

specified for the project (Figure

4^

).

Unfortunately, it is common for the designer