FTA (изд-во). Flexography: Principles And Practices. Vol.1-6

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Individual lines of type can be justified.

When using type, the designer should take

into account the aesthetics, as well as the

press characterization information provided.

The designer should consider the size of posi-

tive and reverse type, line weights of the type,

the number of colors used, registration toler-

ances and trapping type. Other factors to be

considered are the origin of fonts, text wrap,

outline or stroked type, attributes or styles

and special kerning specifications. Listed

below is an explanation of characteristics that

should be considered when selecting type.

Size. The minimum size of the type is based

on print segment and the press characteriza-

tion data. Six-point type for positive and 8 pt.

type for reverse or knockout copy are the

general industry standards for wide web.

Four-point type for positive copy and

six-point for reverse copy is commonly seen

in the narrow-web field. When dealing with

small type sizes, try to avoid typefaces with

serifs and delicate strokes.

Line Weight. The press characterization data

includes the minimum line weight that can

be printed and the minimum reverse line

that can be held open. Whether utilizing a

serif or sans serif font, these minimums can-

not be exceeded.

Color. Type should always be created with

the fewest possible number of colors. As a

rule, you should never use a combination of

more than three colors for type. Remember,

the looser the registration tolerances, the

fewer the colors; and the smaller the type,

the fewer the colors. Where colors overlap

to maintain register, related colors are

preferable to complementary colors because

the latter may produce an undesired third

color in the overlapping area. Where this

can’t be avoided, as when printing yellow

type matter within a solid blue field, the

undesirable discoloration around the letter-

ing may be minimized by printing the yellow

under the entire blue field if the color it cre-

ates is acceptable.

Logo colors are usually made up of spot

colors to achieve the customer’s color

requirements. If this approach is used, the

graphic file must have the logo color speci-

fied as a spot color and not a process color.

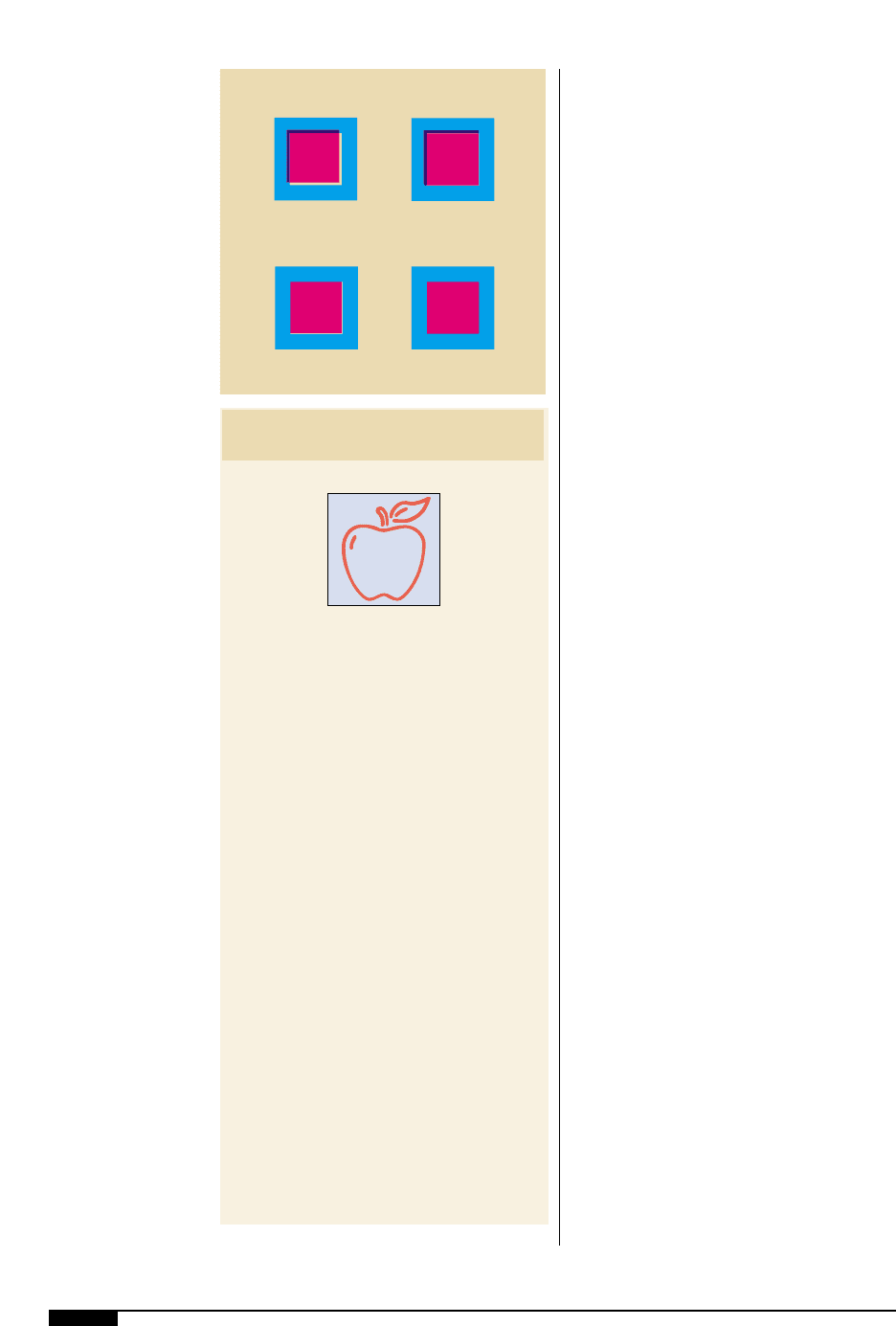

Registration. Although today’s sophisticated

presses are able to maintain fairly tight reg-

ister, it is still a good policy to avoid hairline

or butt register situations. Registration prob-

lems can occur anywhere that two or more

colors adjoin. Printing presses are not con-

sistently precise, due to the speed and force

with which the substrate is pulled through.

Even very small shifts in registration can

cause noticeable white gaps if not compen-

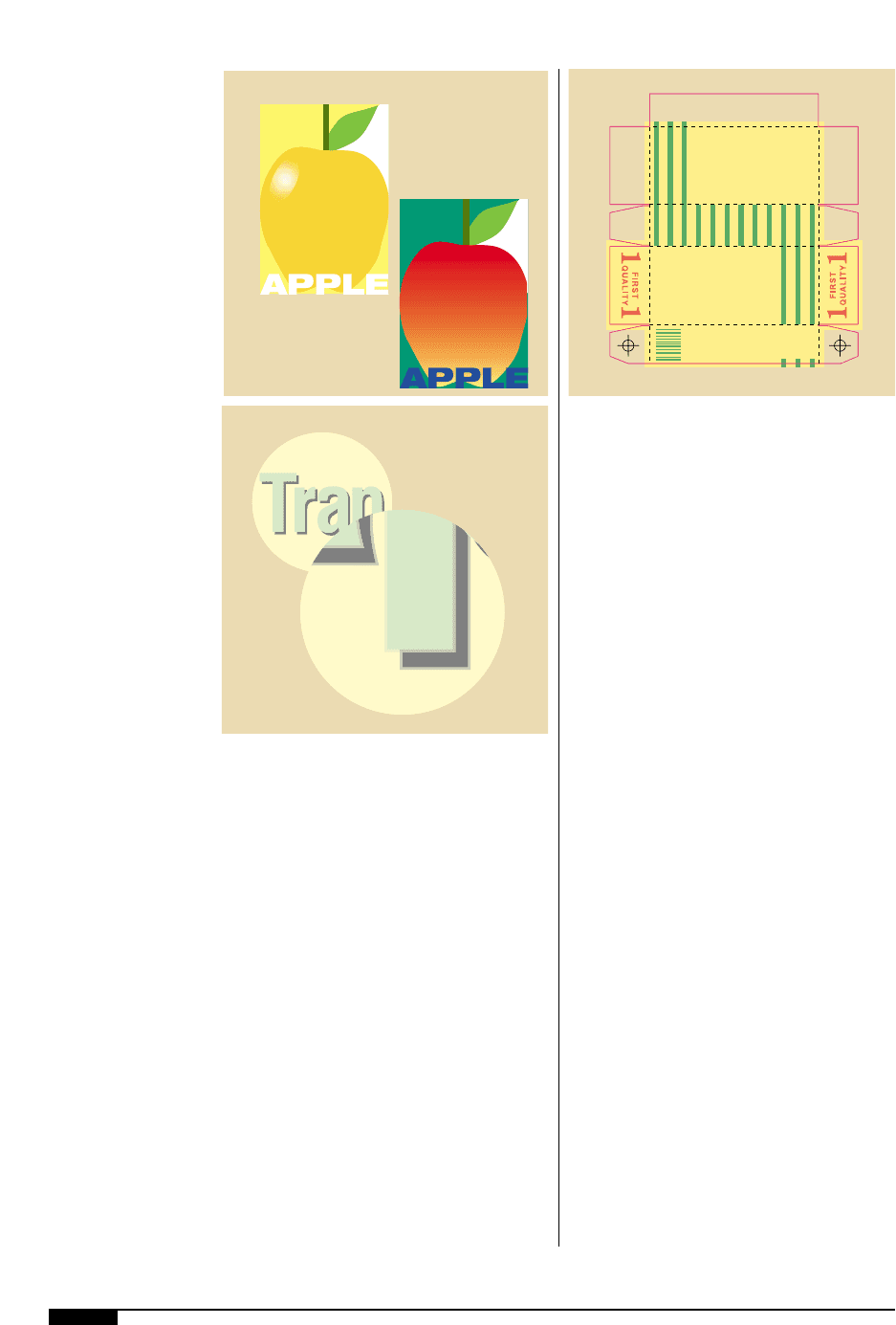

sated for (Figure

1*

). In wide web, 1/32" is

the accepted tolerance if a design is pre-

pared for a CI press. For a stack press, 1/16”

is preferred. Corrugated printers look for

1/4" whenever possible, while narrow-web

printers frequently work with less than 1/64".

If in doubt, the designer should talk to the

printer/converter’s production staff about

their equipment and personnel capabilities

(Table 4).

Trapping. It is very difficult to read type that

is made up of two or more colors and out of

register. With larger type sizes, a solid hold-

ing line is usually applied to the type to hide

any possible registration problems. Many

logos contain two words that are in different

colors. If these two colors are out of register,

the two words will overlap or misalign. A

distance that is at least twice the image trap

is recommended to separate different color

text (Figure

1(

). Applying a colored stroke

or outline to the type can trap computer-

generated fonts. The amount of the trap

applied to a font is dependent on the size of

the type, the kind of substrate being printed

on and other variables. As a rule, the smaller

the type, the smaller the trap that is required

to prevent distortion of the letterform

(Figure

2)

). The amount of trap required for

proper registration ordinarily depends on

• the type of printing press involved;

DESIGN 27

28 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

• the design intricacy;

• the substrate;

• the number of colors;

• the printability, flow, colors, and

• the opacity of the inks.

A central impression press may hold regis-

ter better than an in-line or stack press, espe-

cially on flexible webs and may need less

trap. A fine-line, six-color illustration on

coated stock might take a 0.030" trap, while

three or more times as much may be needed

in a poster-style illustration printed on kraft

stock. When printing related colors, a more

generous overlap may be acceptable than

when printing complementary colors.

Trapping complementary colors is likely to

cause an objectionable third color.

When transparent colors are overprinted

to produce second and third colors, butt reg-

ister is often necessary. In such cases, take

great care in handling color register. It’s

often wise to use outlines where the over-

printed colors touch to prevent the appear-

ance of misregister.

Origin of Fonts. There are thousands of type

fonts available in both TrueType and

PostScript formats. Though TrueType fonts

are prevalent in the desktop industry, they

do not always RIP (raster image process)

correctly, so they are generally not support-

ed and should be avoided. Type 1 PostScript

fonts are recognized as the industry stan-

dard and contain both an outline font (print-

er font) and screen font (bitmap font). When

using PostScript fonts, both files must be

installed on the output system. To ensure

that the fonts will output correctly, it is nec-

essary to include both the outline and screen

font with the file. If a design requires a

unique font, the designer should convert the

type to an outline. This is only recommend-

ed if it is a large type size and a minimal

amount of type (Figure

2!

).

Text Wrap. When automatic type wrap

options are on, text will reflow every time an

1*

Even if film is prepared

correctly, there are

often problems with

holding exact registra-

tion due to the substrate

stretching or shifting

during printing. Even

minute shifts can cause

visible problems.

No Trap

Misregistration

Good Registration

Trap

No Trap

Trap

1*

Table 4

DOES THE ARTWORK

REQUIRE TRAPPING

NO:

No colors

touch, or col-

ors that do

touch have a

common color

element (C,

M, Y or K).

DO-IT YOURSELF

OPTIONS:

■

Manual trapping:

Common controls

within graphic pro-

grams provide do-it-

yourself trapping,

once you’ve mas-

tered trapping con-

cepts.

■

Automatic trapping:

Some programs

include automatic

trapping features that

will make trapping

decisions for you.

While such programs

are sophisticated,

successful use of

these automatic fea-

tures requires some

knowledge of trap-

ping concepts and

familiarity with the

methods used by the

program. Also, they

cannot create traps in

art that has been

imported from anoth-

er application.

PREPRESS OPTIONS:

■

Manual trapping:

For a fee, the pre-

press provider will

prepare the traps

using the controls in

the graphics soft-

ware.

■

Automatic trapping

software: Many

prepress providers

use sophisticted

trapping software

that can automati-

cally trap artwork,

including imported

graphics.

■

Automatic trapping

during imageset-

ting: Some RIPS

automatically trap

files as they are out-

put, resulting in little

extra time or cost.

QUESTIONS TO ASK:

Which colors should spread

and which should choke?

Where do traps go?

How much trap is needed?

YES:

Colors that do

not share a

common ele-

ment (C, M, Y

or K) touch

each other in

this file

image is placed or replaced. If the image is an

FPO (for position only) and the separator

replaces it with the high-resolution image,

the text might reflow differently and the sep-

arator must then manually flow the text to

match the original design. Most software pro-

grams allow the user to create polygons for

the text to wrap around instead of the actual

image. When polygons are used, the text

does not reflow if the image is replaced.

DESIGN 29

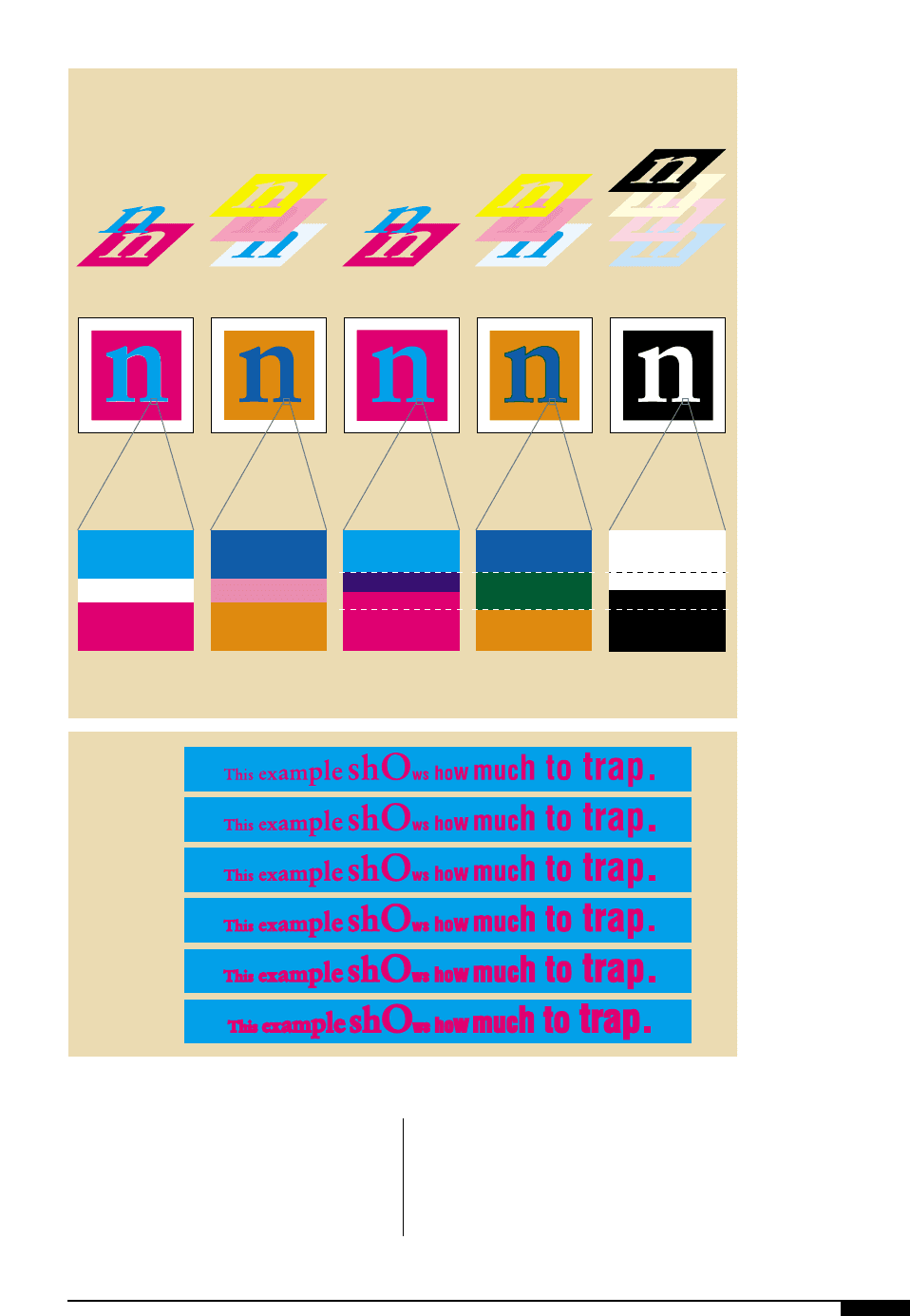

1(

There are a variety

of ways that trapping

type can be handled

including top to bottom:

No trap, uncommon

colors; no trap,

common colors; trap,

uncommon colors; trap,

common colors; trap

with black.

2)

In the example shown

you can see how differ-

ent trap values affect the

serifs as the size of the

trap is increased.

100M

Paper

100C

No Trap,

Uncommon Colors

No Trap,

Common Colors

Trapping with

Uncommon colors

Trapping with

Common colors

Trapping with

Black

Full thickness of

the stroke traps

Half the thickness

of the stroke traps

8C 60M 100Y

100M

8C 60M

100C 100M

100C 60M

100C

30C 25M 20Y

100K

100K

Paper

8C 60M 100Y

100C 100M

100C 60M

1(

None

0.001 in.

.1 pt.

0.003 in.

.24 pt.

0.006 in.

.5 pt.

0.009 in.

.75 pt

0.012 in.

1.0 pt.

2)

30 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

Outline or Stroked Type. Thin outlines around

a tint should be in the same color as the tint

(Figure

2@

). If a trap outline is being creat-

ed, the line weight must be at least twice the

specified trap allowance because both the

background color and text color have to trap

to this outline. After the stroke has been

applied, it is important to verify that the

“counters” (holes in letters such as a, b, D

and R) or serif areas have not closed up. It is

best to not stroke large amounts of text as it

does make the file larger and slows down

the processing time.

It is recommended that when an artwork

file has an embedded EPS file containing

type, the text should be converted to paths

or outlines to avoid RIP conflicts. But con-

verting type to an outline is not recommend-

ed to resolve standard font conflicts. When a

typeface is converted to paths, the copy is no

longer editable and the conversion process

can degrade the quality of the text, especial-

ly small type sizes. If possible, it is better to

include all fonts (even those that reside in an

embedded EPS file) with the artwork file to

be output.

Attributes or Styles. The typefaces in a file

should never have an attribute or style

applied to them. Attributes and styles are

convenient tools available in most desktop

applications that can be used to modify type-

faces. When attributes are used on a font, it

will appear on the screen as a modified face,

and may even print to your proofing system

correctly, but it is not guaranteed that the

selected style will be applied to the typeface

upon output. It is always best to use the

actual fonts available in the software pro-

gram (Figure

2#

).

Special Kerning Specifications. Any modified

kerning, tracking tables or suitcases must be

supplied to the separator with the final

graphic file. Failure to do so will cause all of

the modified information to be ommited

from the final separated graphics.

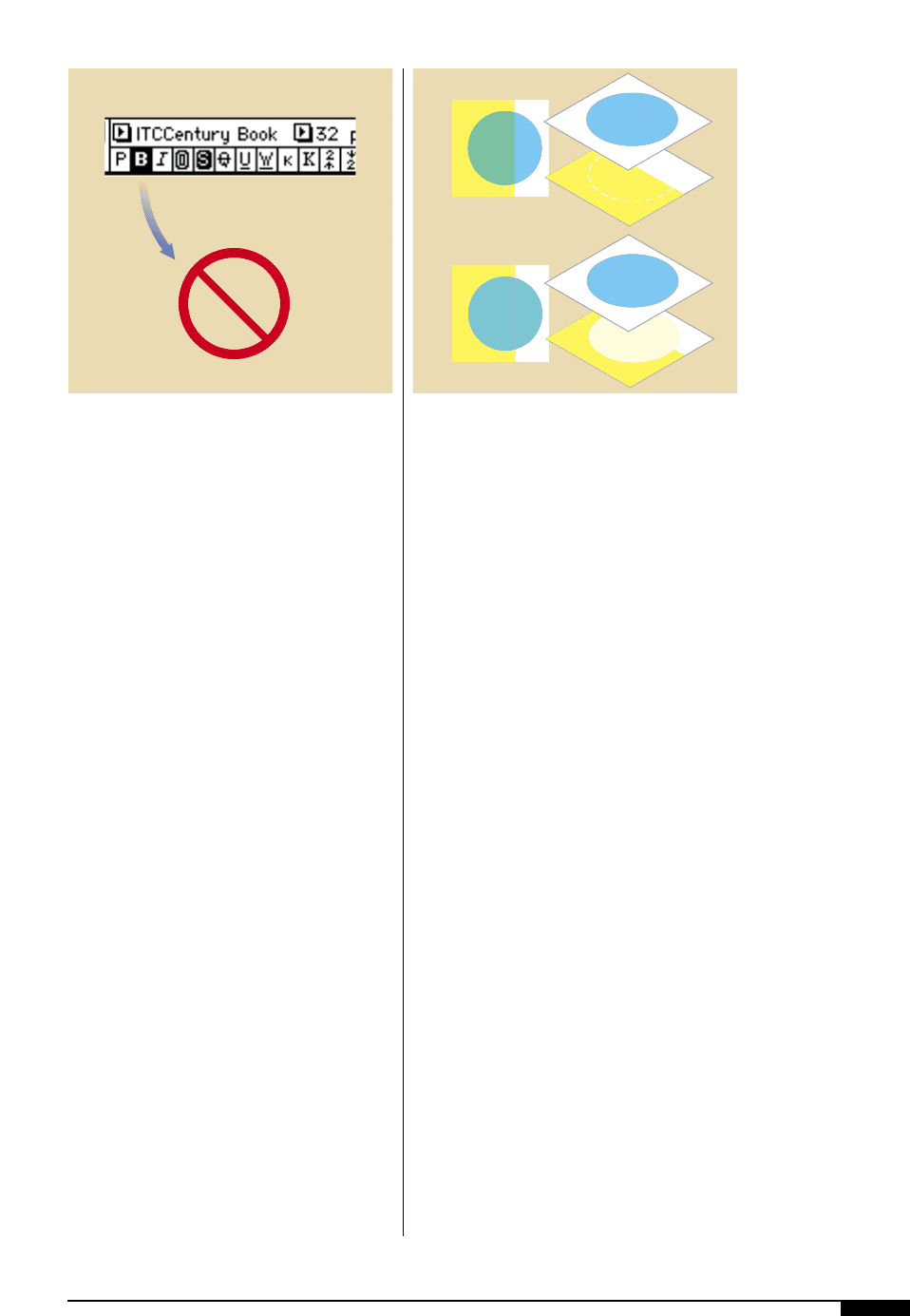

Overprints

An overprint is when one solid color prints

on top of another solid color. Overprinting

graphic elements might seem like the perfect

solution for eliminating undesirable traps.

This is especially true when the designer

wants to use small graphics that are sur-

rounded by another color. The designer

should be aware of some overprint limita-

tions. Dark-colored graphics overprinting a

light color can work very well. On the other

hand, overprinting light colors on top of

darker colors can change the look and color

of the overprint to something undesirable –

think of a yellow printing on top of a cyan vs.

green overprinting cyan (Figure

2$

). When

2!

Font icons identify the

type of file (screen or

printer), the maker of

the font (foundry) and

whether it is TrueType

or PostScript.

2@

Outlines around type

should be the same

color as the body of

the text.

2@

PostScript Type 1 or 3

TrueType

2!

you overprint colors with shared inks, com-

mon ink values will not combine. Illustrator

has a filter called “trap hard” and trap soft”.

These filters can be used by the designer to

view a simulation of what an overprint will

look like when printed.

Trapping

Trapping is a major concern in the flexo-

graphic industry because of the unique reg-

istration tolerances on a flexographic press.

Trapping is used to compensate for any pos-

sible registration problems. The trapping

requirements used for flexography are often

larger than those used for an offset press.

Most designers are not required to build

traps into an artwork file and therefore are

unfamiliar with requirements for trapping.

However, it is important to be aware of how

much trap will be applied to the graphics so

that good design decisions can be made in

creating the graphics. Desktop application

software has tools or special features that

allow a designer to trap the artwork, but it is

usually the job of the separator to build trap-

ping into an artwork file.

Trapping is simply enlarging a print ele-

ment so that the edges that come into con-

tact with other elements overlap (overprint)

by a specified amount. The amount of trap-

ping required for an artwork file varies from

press to press. Each press has a set of toler-

ances and operating parameters. The trap

radius is one of the tolerances that a flexo-

graphic press should be characterized or fin-

gerprinted for and then applied to all art-

work that will be printed on that press.

Trapping is a necessary stage in the prepress

process that compensates for the registra-

tion tolerance of a printing press.

Trapping can change the appearance of art-

work. Some colors create dark lines where

they overprint another color (Figure

2%

).

This dark line, the trap, then becomes a visi-

ble element in the overall design and in some

cases can be distracting to the artwork’s

overall appearance. Sometimes the trap can

be modified to make it less obvious, but it

cannot be removed. It is in the basic design

of the artwork that trapping problems can be

avoided.

Vignettes and gradient fills can be difficult

to trap because of the gradual change of the

tint values that occur in a gradient fill. If the

vignette is trapping to an element that is a

100% solid color, the trap is easier to hide.

But if a design has a vignette abutting a sec-

ond vignette, the trapping can become much

more difficult and visually unappealing. With

some prepress systems, trapping vignettes

can even be impossible to do.

Drop shadows in a design are also difficult

DESIGN 31

2#

You should always

check to see that

typefaces do not have

an attribute or style

applied to them which

will modify the face

and could create prob-

lems upon output.

2$

Overprinting objects

without common ink

colors, combines the

ink values where the

objects overlap.

Overprinting objects

that share inks show

only the overprinted

color where the objects

overlap.

2#

50% M

60% C

20% Y

60% C

80% Y

80% Y

80% Y

60% C

80% Y

60% C

20% Y

2$

Design

32 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

to trap and tend to create some unusual

looking results on the final printed piece. An

example of unusual trapping would be a

bold typeface, colored in a pale green and

sitting on top of a 50% black drop shadow,

with the entire image on a background of a

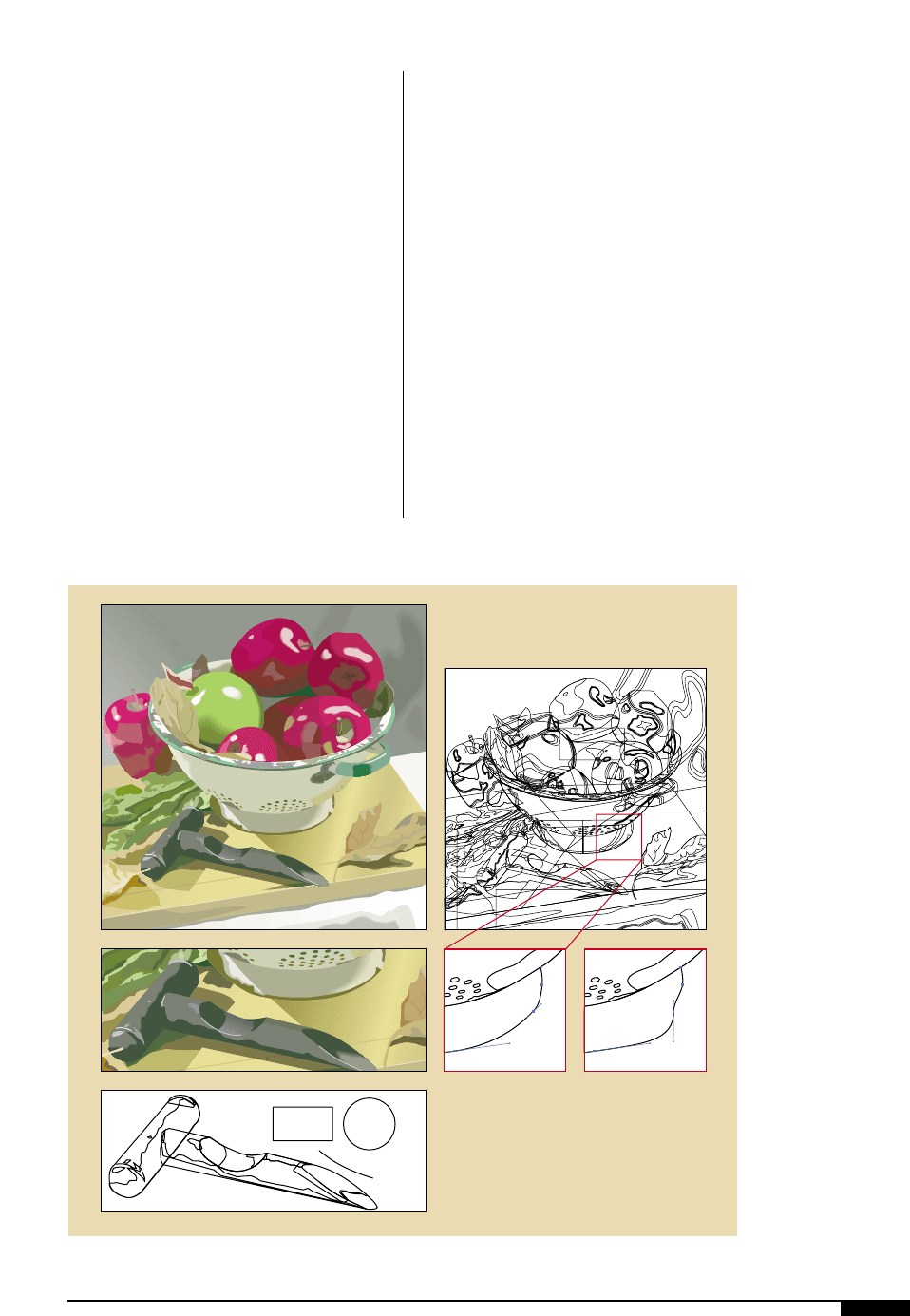

pale yellow (Figure

2^

). The typeface would

be lighter than the drop shadow and would

have to spread into the shadow. The back-

ground yellow would have to spread into

both the shadow and the green type.

Die Lines

Most packaging graphics have to be

placed according to die-cut scores, cuts and

folds (Figure

2&

). Therefore, the final pack-

age must incorporate print-to-print and

print-to-cut (or fold) registration. Specifi-

cations for the positioning of graphics in

relation to the location of die-cut scores,

folds and cut line, will vary depending on the

press width and press type, and must be

adhered to by the designer.

Die lines can be requested from the die

maker’s CAD (computer-aided design) sys-

tem, usually as an EPS or Adobe Illustrator

file. The die lines from a CAD system will

accurately show all cuts, perforations and

score lines being made on the final project

from the die maker’s perspective. Die lines

require exact dimensional accuracy (for

example: 2.000, not 1.998 or 2.003 for a 2"

dimension).

Illustrations

Many tools available for a designer to cre-

ate illustrations. Many formats used to build

illustrations prove difficult to separate and

then print on press. Some of these difficul-

ties relate to the way the illustration was cre-

ated and some to the actual makeup of the

illustration. Thin lines, strokes, trapping,

gradations, pattern fills and other elements

can cause difficulty when trying to maintain

the integrity of the illustration on the flexo

press.

When selecting color for an illustration,

there is no limit. But a smart designer will

use one plate or a spot color to define the

2%

The trap line must be a

wider thickness and

overprint the original

object.

2^

Drop shadows are often

difficult to trap and can

create unusual looking

results on the final

package.

2&

Die lines provided by

the die maker will

ensure accurate

positioning of all

graphics to the cutting

and folding lines.

America’s Choice Butter

America’s

Choice

Butter

America’s

Choice

Butter

2&

2^

Page Designed

to Avoid Trapping

Page Which Will

Require Trapping

2%

stroke for the illustration. Two or more

plates can successfully define color areas

inside an illustration, but areas that are

defined in this manner should be chosen

carefully. Broad color areas that abut bold

strokes are more forgiving with press mis-

registration than small color areas that abut

thinner strokes. Another problem that can

occur when coloring an illustration is “gaps”.

Gaps can occur when a file is created in such

a way that an illustration’s strokes are

placed on top of color areas that contain

separate elements of the illustration. An area

that has an abutting or underlying color area

should be magnified to see that the elements

are flush with one another and that the color

areas are under the stroke.

Another culprit of gaps is an open path or

strokes with a color fill assigned to them.

Strokes should have no color fills assigned to

them. If the file is not void of gaps, problems

could occur during the trapping phase of the

artwork.

Object-oriented Artwork

Object-oriented graphics, also known as

vector graphics, are shapes such as curves

and line segments, mathematically defined

across an invisible grid. Simply using the

mouse to select and drag individual or

groups of control points can reshape object-

oriented graphics. Vector graphics are reso-

lution-independent, which means that they

can be printed or displayed at any resolution

that a printer or monitor is capable of

(Figure

2*

).

DESIGN 33

2*

Object-oriented images

are made up of drawn

objects such as circles,

squares, lines and

complex curves called

paths. Object-oriented

images are defined by

points which are used to

manipulate the image.

2*

34 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

Auto-trace and vector graphics. Should a

designer decide to create a design the “old-

fashioned” way by hand drawing with a pen

and ink or pencil, the illustration must be

scanned into the desktop environment. Once

scanned, the design is converted to line work

using a vector conversion application such as

Adobe Streamline or an autotracing feature

available in Adobe Illustrator or Macromedia

FreeHand. Autotracing and vector conver-

sions are not very accurate in recreating the

original image because additional points can

be added to a path. These additional points

can alter the shape of the original line, add

more data than is necessary and slow down

processing. It is crucial that settings are cor-

rectly used or the traced illustration may be

reproduced with an excessive amount of

control points along the illustration’s paths.

Artists should also try to avoid long, continu-

ous paths. Paths that are complex with many

points can cause problems during the pre-

press processing of the electronic file. The

cleanest lines are the lines created with the

fewest points (Figure

2(

).

Pattern Fill. A further consideration to be

taken into account when coloring an illus-

tration is pattern fill (Figure

3)

). Fills are

great looking, fun to work with, create

impressive results and are easy to use – truly

a designer’s dream come true! But, they can

be a production artist’s nightmare. Pattern

fills modify an electronic file’s integrity in

ways that are not evident to a designer. Still,

pattern fills make electronic files difficult, if

not impossible for many prepress systems to

process. Pattern fills should be avoided, or

before using, test the output of the pattern on

the output device. One of the processing

problems with pattern fills is that the RIP can

have difficulty interpreting the pattern data.

Sizing. At times, an illustration is reduced in

size after being created. For instance, an

illustration might be reduced to fit onto a

side panel of a package. This reduction can

cause problems with the printability of the

illustration. Line weights, type size and trap

areas may become smaller than the mini-

mum specifications.

Complexity. Some illustrations can be very

complex, containing many graphic elements

like patterns, gradations, colors, varying line

weights, text and more. When a separator is

working on this type of illustration, the lay-

ering of the elements can change, making it

very difficult for the separator to get all ele-

ments back into the correct layering order.

The illustrator should try to group “like”

objects together or elements within one

object together, to avoid this problem.

Bitmapped Graphics

A bitmapped image is defined pixel-by-

pixel and has a fixed resolution. (A pixel,

2(

To avoid problems

during the prepress

processing of electronic

files, the production

artist should simplify

paths.

3)

Fills are great looking,

fun to use and create

impressive results,

but they can cause

processing problems in

interpreting the pattern

data at the RIP.

2(

Pattern

Fill

3)

short for picture element, is a square of

color). Bitmapped artwork can be drawn,

painted or scanned onto the computer. The

simplest of computer graphics are defined by

one bit of data per pixel, which instructs the

computer to display a black dot or a white

dot. Color graphics utilize four to 24 bits of

data per pixel.

Resizing a bitmapped graphic changes the

size of the individual pixels. A 2" x 4" image

scanned at 72 dpi will look fine on the moni-

tor, but enlarging the image to fill the screen

will create an unsatisfying picture.

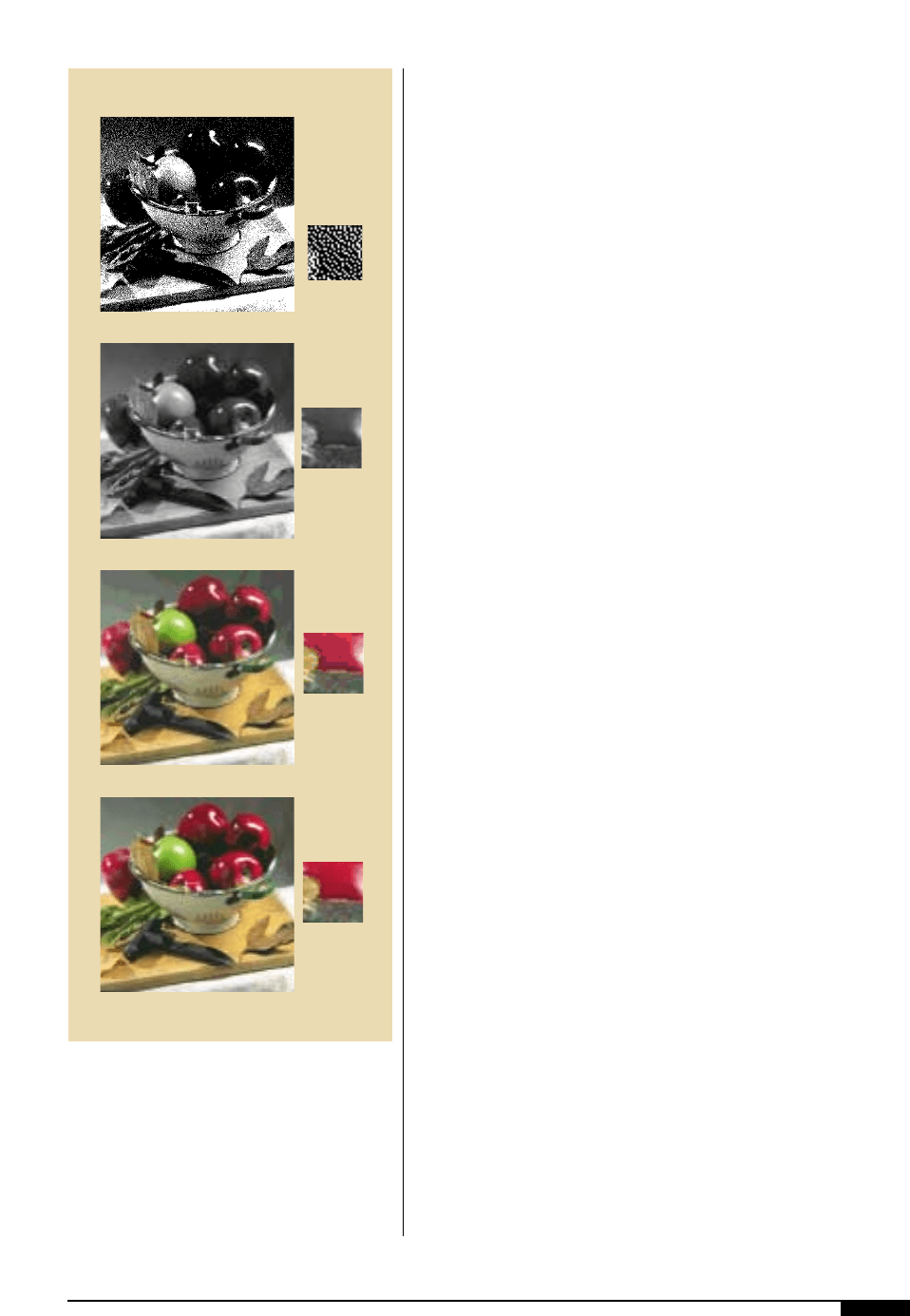

Printing bitmapped graphics can present

additional problems, which must be taken

into account during the preparation of the

file. Continuous-tone color or grayscale

images must be converted into halftones for

conventional printing. The final printed res-

olution and method of screening must be

known before a bitmapped image is created

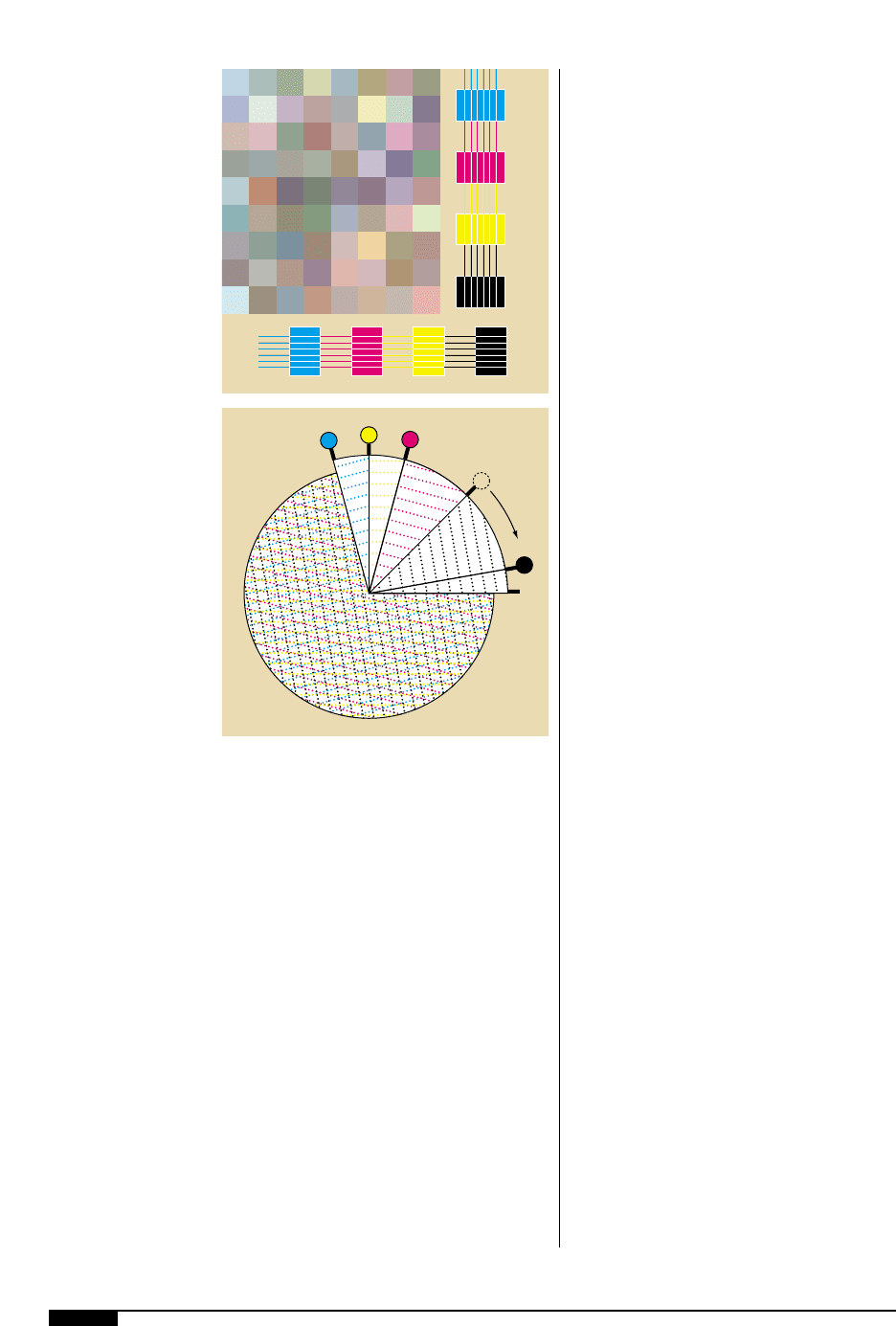

(Figure

3!

).

Line Drawings and Clip Art

Drawings made up of solid lines are fre-

quently used in packaging design. The

designer can create the line drawings, hire

an illustrator for the job, or use clip art. Clip

art needs to be carefully evaluated and

selected if it is going to be used in the design.

Some clip art is of very good quality and is

saved in usable formats, while other types

can cause major problems. Before choosing

clip art the following should be checked:

• File format is one that can be easily

edited by the designer or separator,

such as a vector EPS.

• Pixel artwork saved at the correct reso-

lution, 300 dpi for printing.

• Artwork paths in clip art do not contain

an excessive number of points or prob-

lems could occur when the file is out-

put.

• Colors used in clip art can be easily com-

bined with the colors available on press.

Care must be taken to be certain that all

colors are converted to the color palette

available for the job.

Line Weight. Expect an increase in line

weight of positive lines and a decrease in

line weight of negative lines in the finer, nar-

DESIGN 35

3!

A 24-bit continuous-

tone image can be

depicted with up to 16.7

million colors, but the

size of the file will be

much larger than a

similar image created

with 8 bits per pixel.

3!

1-bit

8-bit (grayscale)

8-bit (indexed color)

24-bit (true color)

36 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

rower lines of illustrations, just as with

smaller type sizes. Compensate for this by

drawing positive fine lines slightly thinner

and reverse lines slightly heavier than the

line value desired in the final print. Line

thickness tolerances vary from press to

press, so it is necessary to refer to the press

characterization data for the line-weight

minimums (Figure

3@

). If you supply art

with a line weight less than the printers’

specifications, the separator will need to

make the line weights heavier to meet the

printers’ capabilities.

Dots. The same thing happens to dot sizes in

tints and screen values. According to your

own printing circumstances, compensate

about 10% to 20% for dot growth when

selecting screen values.

Be sure to consider the web direction and

linear direction of dots in tints, monotones

and duotones as they are applied to the art.

The cells of the anilox ink metering roll usu-

ally run 45° to the web direction. Therefore,

the direction of the dots in the screen should

be angled off those of the anilox roll to avoid

possible moiré patterns. A moiré pattern can

occur when two or more screen angles that

are too close to each other are used. When

screen angles conflict, they create a variety

of objectionable patterns instead of the tone

values you want (Figure

3#

).

PHOTOGRAPHY

When the designer takes part in planning

photography for the design, he/she can pro-

vide parameters that will ensure the suc-

cessful printing of any photograph.

Highlights. Offset photographers might try to

accentuate the highlight area of a product or

make the highlight a focal point of the image.

The same approach can be used with some

photos that will be printed flexo, but must be

carefully addressed. Remember that general-

ly, the smallest flexo dot that will print is 3%

and the 3% dot, with dot gain, will actually

print at around a 12% dot.

Shadow. The shadow area requires the same

considerations as the highlight area. Large

shadow areas could fill in. As a result, the

detail will be lost and the shadow area will

just appear dark.

Amount of detail. The clarity of the photo-

graph is directly related to the line screen at

which the photo will be printed. Clarity is

dependent upon the number and size of

objects and the amount of detail. For

instance, if an image is going to be printed at

175 lpi, the detail and small objects will have

clarity and look good. If the same image is

going to be printed at 100 lpi or 85 lpi, the

detail and small objects may not print as well.

Digital Photography. With digital photogra-

phy, the photographer can play the role of

3@

Typical line-weight

scale from a press

characterization target

used to determine

minimum capabilities.

3#

Examples of a moiré

pattern which occurs

when the angle of the

anilox roll is not taken

into consideration

before choosing

screen angles .

105°

90°

75°

10°

0°

3#

3@