Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

10. Important Productions and

Collaborations in the Verrocchio Shop

P

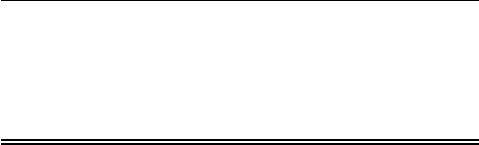

robably in those free-spirited days as a member of the

Verrocchio crew, Leonardo drew in metalpoint on blue paper

the elegant, if disturbingly fetching, nude figure of John the Baptist

pointing – the first of his many enigmatic and increasingly androg-

ynous or homoerotic portrayals of the saint (fig. 20). Beyond any

imposition of personal tastes onto his subject, Leonardo, in feminizing

John – and other male saints and angels – probably intended to sug-

gest that in divine beings, genders are combined and transcended. The

refined study may have been Leonardo’s contribution to the design of

an altarpiece called the “Madonna di Piazza,” representing the Virgin

and Child with Saints John and Donato, commissioned by the Medici

around 1475 from Verrocchio’s shop for an oratory chapel in Pistoia

Cathedral (fig. 21). Eventually, another assistant, Lorenzo di Credi, was

entrusted, it seems, with the entire execution of the altarpiece, but he

probably availed himself of Leonardo’s gracile drawing in conceiving

the figure of the Baptist.

By the mid-fifteenth century, the pointing pose of the saint had

become canonical in art; he was also frequently depicted holding or

wearing a banner with the words, Ecce Agnus Dei (Behold the Lamb

of God), his proclamation of Christ’s divinity and sacrificial nature,

reported in the Gospel of John (1:36). However, the Baptist, a patron

saint of Florence, usually appears in art either as a very young boy or

as an unattractively weathered ascetic, grasping a slender reed cross.

Here, Leonardo seems to delight in conveying the sensuous anatomy

of his adolescent model, whose holiness appears questionable and

whose pointing gesture lacks conviction. The painter may have found

justification – and even the idea – for his depiction in Donatello’s

67

68 The Young Leonardo

Figure 20.

Leonardo da Vinci,

St. John the Baptist,c.

1475–76, silverpoint on

blue prepared paper,

Windsor Castle, Royal

Library (12572). The

Royal Collection

C

2010 Her Majesty

Queen Elizabeth II.

marble, pubescent Saint John of the 1440s or, more likely, Benedetto

da Maiano’s sculpture of a lanky, teenaged Baptist (c. 1476–78), either

in progress or recently completed, for the niche over the door of the

Sala dei Gigli in the Palazzo della Signoria. Yet Leonardo’s saint lacks

the youthful awkwardness and innocent piety of those Saint Johns.

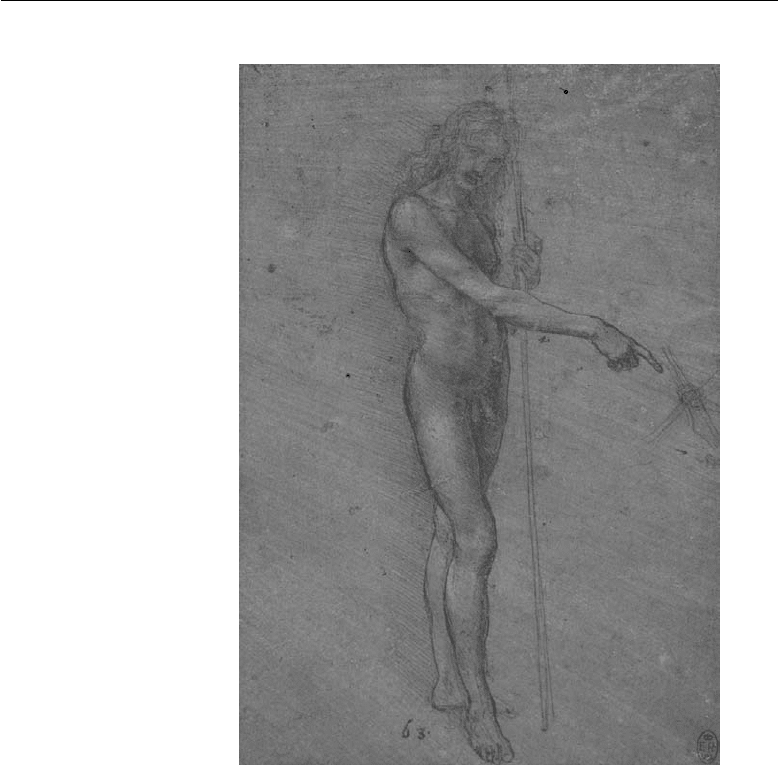

Not one to conspire in trend setting, Credi prudently aged the figure

when he translated it into paint.

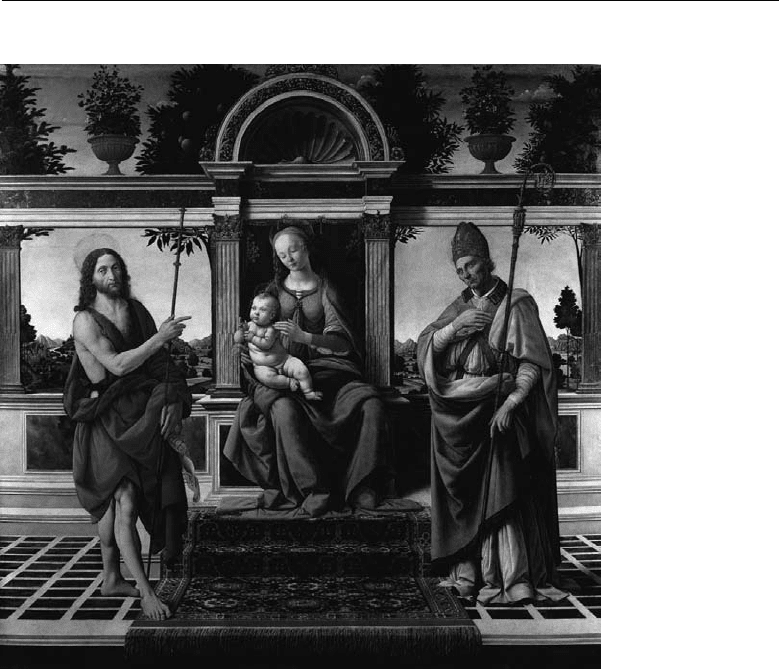

Although the touch of Leonardo’s brush cannot be discerned in

the Pistoia altarpiece, his participation, perhaps at the same moment,

in the execution of Verrocchio’s beautiful Baptism of Christ (begun

c. 1468–69, resumed and finished c. 1475–76) for the monastic

church of S. Salvi has been well observed and for centuries extolled

(fig. 22). Prone to embellish and mythologize, Vasari related that

Leonardo was responsible for painting the angel in profile at left – a

10. Important Productions and Collaborations in the Verrocchio Shop 69

Figure 21.

Lorenzo di Credi,

Virgin and Child

with Saints John and

Donato,c.1475–76

oil on panel, Pistoia

Cathedral. Niccol

`

o

Orsi Battaglini/Alinari

Archives, Florence.

figure, the writer gushed, so gloriously rendered and superior that an

embarrassed Verrocchio, who executed the lion’s share of the picture,

decided thereafter to turn his attention exclusively to sculpture. It

is difficult to determine the exact division of labor in the painting,

but Leonardo’s intervention would seem to extend well beyond the

crouching angel to many of the landscape details and to the figure

of Christ. Evidently, the young artist had by this time risen to the

position of full-fledged collaborator. It should be recalled that he had

enjoyed the official status of an established painter since 1472, when

he was admitted to the painter’s professional confraternity.

Leonardo’s involvement is unmistakable in the handling of the

baptismal river’s banks and flowing water, which finds its source in his

familiar, distant mountains and meanders gradually through the entire

landscape, carving its way toward the viewer. This depth-defining

motif may have been inspired by similar features in the backgrounds of

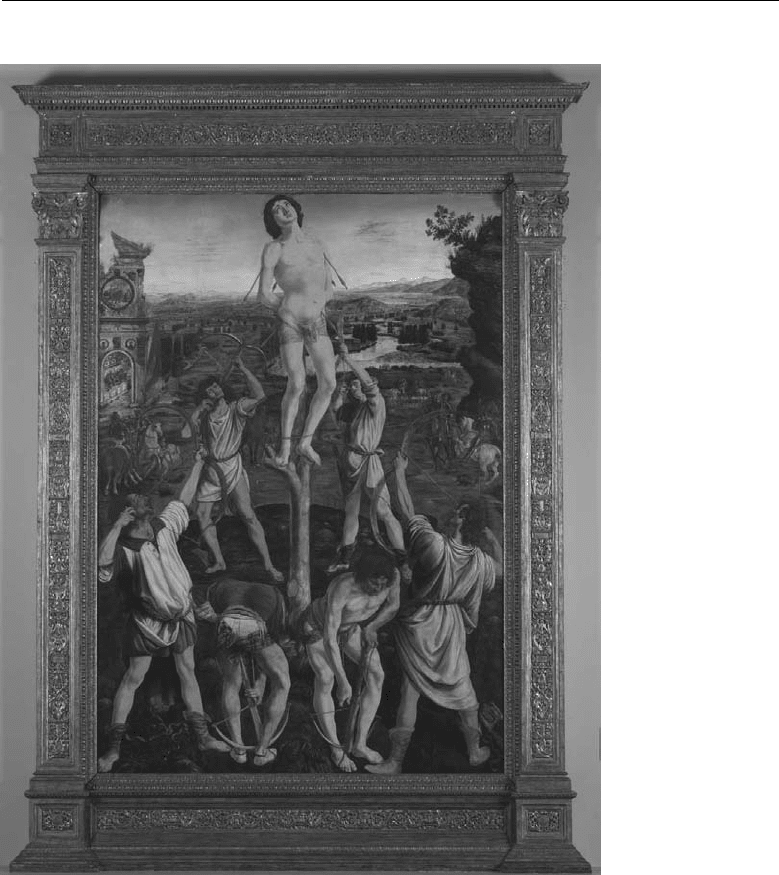

a few paintings by the Pollaiuoli, such as Antonio’s bold Hercules and the

Hydra for the Medici palace and the Shooting of Saint Sebastian (c. 1475;

70 The Young Leonardo

Figure 22.

Andrea del Verrocchio

and Leonardo da Vinci,

Baptism of Christ,c.

1468–69 and c. 1475–76,

oil on panel, for S.

Salvi, now Florence,

Uffizi. Scala/Ministero

per i Beni e le Attivit

`

a

culturali/Art Resource,

NY.

fig. 23) by both Antonio and Piero, a picture that Leonardo would have

admired in the Pucci family oratory beside the Florentine church of SS.

Annunziata. Leonardo carried the river idea much further, however,

needing to unify spatially a work created sporadically by two hands

over a period of six years or more. He rendered his more pervasive

body of water with a geological awareness, exaggerating the erosive

effect of the river on the surrounding topography.

With utmost confidence, Leonardo apparently took it upon him-

self as well to create or revise the central figure of the Savior. To

unify the luminosity of the picture, Leonardo painted or repainted,

in oil, Christ’s flesh with soft, gray tonalities that are in keeping with

the shadowy background. In later pictures, Leonardo would much

exaggerate this sooty, gray quality, which tends to blur the edges of

figures and objects, to obtain an atmospheric effect that would come

10. Important Productions and Collaborations in the Verrocchio Shop 71

Figure 23.

Antonio and Piero del

Pollaiuolo, Shooting of

Saint Sebastian,c.1475,

oil on panel, London,

National Gallery.

C

National Gallery,

London/Art Resource,

NY.

to be called sfumato (“in smoke”), one of his most admired inno-

vations. Yet even here, the vibrancy of this surface treatment works

successfully to meld Christ’s head and torso with the misty back-

ground and surrounding air. Consequently, the figure, which recalls

in its lean muscularity Leonardo’s metalpoint Saint John the Baptist,

contrasts sharply with Verrocchio’s more dryly delineated and rough-

hewn saint. Above them, still more incongruous, an old-fashioned

feature has been added for the conservative, pious monks of S. Salvi:

the disembodied hands of God the Father release the dove of the Holy

Spirit, a detail probably quoted from the mystical Adoration of the Christ

72 The Young Leonardo

Child that Filippo Lippi painted for Piero de’ Medici’s wife, Lucrezia,

more than a decade earlier.

Since its day, Leonardo’s angel has been admired for the vitality

and complexity of its pose and lustrous “waterfall” of hair. These fea-

tures suggest or heighten the momentary quality of the stance of the

divine figure, waiting like a dutiful altar boy to offer Christ a robe

following baptism. With Saint John’s cross and the rocky outcropping

nearby, the cloth is also intended to invoke Christ’s burial shroud –

perhaps accounting for the particularly solemn and apprehensive

expression of the companion angel. In keeping with Vasari’s story,

that disturbed face has occasionally been read autobiographically as

conveying Verrocchio’s dismay with the comparative excellence of

Leonardo’s shimmering angel. Such an interpretation is highly doubt-

ful, but nevertheless appealing when one examines closely the fresh,

evanescent head of Leonardo’s celestial valet. The painter has indicated

not only the transient sheen of the angel’s hair, but also the watery glint

and transparency of the orbs of its eyes, to which he has deliberately

juxtaposed the spherical crystals on its collar. Leonardo’s proclamation

on talent and maturation, reportedly first said to his math tutor, seems

apt here: “Poor is the pupil who does not surpass his master.”

11. Leonardo’s Colleagues in

the Workshop

I

nitially trained as a goldsmith, the stocky, durable

Verrocchio considered himself a sculptor first and then a painter.

His decisive, midcareer transition from painting to sculpture was prob-

ably a preference and not, as Vasari suggested, a retreat. Certainly, his

contemporaries admired him foremost as a sculptor, an unrivalled

metal caster and engineer. Only in his late twenties, but industrious

and diligent, when he opened his independent business, he proved to

be an excellent foreman, coordinating the activities of a self-contained

shop in accord with time-tested, old-fashioned modes of operation.

For sculpture (even relatively small works), he employed the centuries-

old assemblage technique, in which many separate pieces were cast and

then welded together – every major project involving the contribu-

tions of numerous hands.

The collaborative atmosphere and multitasking demands of his

shop benefited scores of artists who passed through it, including Perug-

ino and the sculptor Francesco di Simone Ferrucci. Leonardo and

Lorenzo di Credi may have been the only assistants who remained for

a decade or more; many other workers probably came and left on an

“as needed” basis. Leonardo, no doubt, thrived in this environment

and would have been galvanized by the challenge of learning so many

diverse skills. However, the detailed, sometimes factory-like approach

could be a bit stultifying for some, such as Lorenzo di Credi, who,

like many Florentine artists, had first apprenticed with a goldsmith.

As a painter, he excelled in the small parts but could never quite grasp

the whole. Even the generally respectful Vasari had to admit that the

well-intentioned Credi was punctilious to a fault.

A great admirer of Leonardo and probably five years his junior, the

tractable Credi imitated his drawings as much as he did those of the

73

74 The Young Leonardo

master and managed to achieve a competent and ingratiating artistic

manner. In a large, busy shop, there was always room for the effective

and dependable plodder. Verrocchio, trusting Credi for his conserva-

tive bent and fastidious ways, would put him in charge of the shop

when he was elsewhere on business. He also knew that he could count

on Credi, his favorite pupil, to execute meticulously straightforward,

conventional pictures, such as the Pistoia altarpiece, with its simple

grouping of fairly static figures. Although, as previously noted, there

has been speculation that Leonardo may have been Verrocchio’s lover,

the master had a much closer personal relationship with Credi, who

was eventually named executor of his will and inherited all of Verroc-

chio’s furniture and clothing, as well as the bronze, tin, and porphyry

left in the workshop at his death.

Of a temperament similar to Credi’s, Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci,

better known as Perugino, gained much in the Verrocchio work-

shop as well. Nearly an exact contemporary of Leonardo, Perugino

probably came to Florence a half-dozen years after him, around 1470,

from desperate conditions in his native town of Perugia. Accustomed

to dire poverty, Perugino reportedly slept in a “miserable chest” for

the first several months after he arrived in the city. Vasari postu-

lated that it was Perugino’s experience of extreme economic dis-

tress and hunger that drove him to study and work incessantly, in

the Verrocchio shop and throughout his life. Such motivation also

spurred him to fast-track his independent career, and by 1475, when

Leonardo was still a rowdy workshop member, Perugino was already

fulfilling important commissions in Perugia and surrounding Umbria,

notably the Adoration of the Magi for the church of the Servites in Colle

Landone.

Whether for reasons of jealousy, personality clashes, or differing

views, the two artists, Vasari reports, became rivals. One can imagine

that Leonardo disdained Perugino’s unadventurous approach to paint-

ing, his inclination constantly to repeat figure types and stock poses

that had proven popular and lucrative. According to Vasari, Perugino’s

contemporaries often taunted him for reusing figures “either through

avarice or to save time.” Perhaps with Perugino in mind, Leonardo

wrote that the “greatest fault of painters” was “to repeat the same

movements, the same faces, and the same style of drapery in one

and the same narrative painting.” And, as someone who declared that

“poor is the man who desires many things,” Leonardo would have

11. Leonardo’s Colleagues in the Workshop 75

Figure 24.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Annunciation,c.1473–

76, oil on panel, for

San Bartolomeo di

Monteoliveto (outside

of Florence), now

Florence, Uffizi.

Scala/Ministero per

i Beni e le Attivit

`

a

culturali/Art Resource,

NY.

abhorred the unbridled venality of Perugino, about whom Vasari said,

“he would have sold his soul for money.”

While in the Verrocchio workshop, Leonardo produced some

paintings completely of his own design and execution, including an

Annunciation (c. 1473–76) for the monks of San Bartolomeo di Mon-

teoliveto (outside Florence), now in the Uffizi (fig. 24). The com-

mission, acknowledging Leonardo’s full professional status, was either

passed to him by Verrocchio or steered to him by his notary father,

who counted that religious institution among his monastic clients.

Created by a still-immature youngster, scarcely past twenty, the stiff

picture was accepted, despite its flaws, by the provincial monastic

clergy, who would have delighted in the brilliant passages of nat-

ural detail and landscape. He spread before them a rich, millefleur

tapestry of flowers within a walled garden, a reference to the hortus

conclusus (enclosed garden) of the biblical Song of Songs (4:12), a pop-

ular source for Marian imagery – and metaphors for her virginity – in

the Renaissance.

His angel, although splendidly garbed, assumes an unnaturally

rigid, hieroglyphic posture. Likewise, the Virgin appears rather

wooden, a fantoccio, an artist’s lay figure or mannequin, whose arms and

hands have been adjusted into position. Such inadequacies may have

resulted from Leonardo’s dependence on clay models when working

out the figures’ poses; he perhaps had neither Verrocchio’s permission

nor the funds to employ living, studio models for an extended period

of time. Compensating for some of these shortcomings, Leonardo used

76 The Young Leonardo

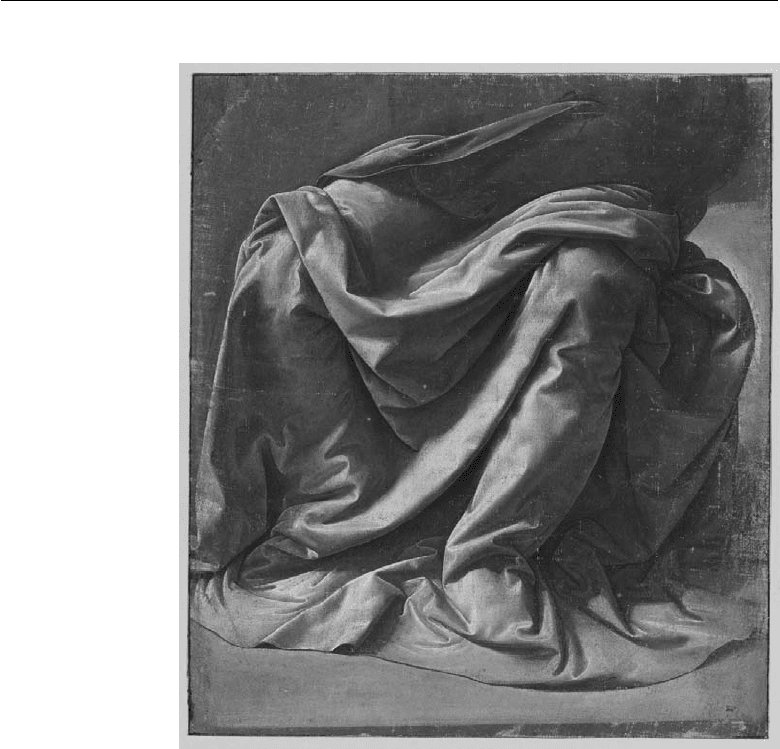

Figure 25.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Drapery Study,

c. 1473–76,pen,

brush and gray tempera

with white heighten-

ingongrayprepared

linen, Paris, Louvre

(2255). R

´

eunion des

Mus

´

ees Nationaux/Art

Resource, NY.

the opportunity to demonstrate everything he had seen and learned

in the Verrocchio shop, from the master’s one-point perspective sys-

tem, to the Virgin’s obtrusive lectern, based on the master’s tomb for

Piero and Giovanni de’ Medici, to her abundant drapery, conceived

through the Verrocchio studio practice of drawing after pieces of

linen that had been dipped in wet plaster and then carefully arranged.

Fortunately, several of these beautiful drawings of drapery, landscapes

in themselves, survive, including the brush-and-wash studies, now in

the Louvre and Uffizi, that served as the models for the dresses of the

annunciate Virgin and angel (fig. 25).

These sheets, together with a detailed study of the angel’s sprig

of lilies, foster the impression of an artist who worked assiduously,

but piecemeal – assembling his composition from well-considered yet

disparate parts (the way in which Verrocchio created his sculptures).

The overall effect of the picture would seem to confirm this; the