Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

14. The Madonna of the Cat 97

Figure 40.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Virgin and Child with a

Cat,c.1478–80,pen

and ink with wash,

New York, Private

Collection.

It was also around this time, in January of 1478, that he received

what is believed to have been his first independent commission, for

an altarpiece (probably depicting the usual Virgin and Child with

Saints) for the Chapel of San Bernardo in the Palazzo della Signoria,

an important civic project that he failed to complete after having

accepted an initial payment in good faith (ultimately returned). We

can assume that the contract for the prestigious altarpiece had Ser

Piero’s fingerprints all over it.

15. Leonardo, the Medici,

and Public Executions

U

nquestion ably, leon a rdo , always seeking new chal-

lenges, had trouble sustaining interest in many of the Floren-

tine art industry’s stock-in-trade products – traditional church altar-

pieces and small Madonnas for domestic display. By the later 1470s,

the Verrocchio shop was fast becoming a mere (sculptural) niche

player in the “Madonna market.” Remembered today foremost for

his mythologies, the Birth of Venus and Primavera (Spring), Botticelli

was, by the early 1480s, the dominant madonnero, maker of painted

Madonnas, in Florence, employing a large corps of assistants to repli-

cate his designs. Leonardo may have felt some professional jealousy

toward Botticelli, whose prosperity stemmed not only from his talents

but also from the favor of Piero de’ Medici, who, years earlier, had

invited the painter to live with him and his family in the Medici Palace.

Rarely does Leonardo mention his very successful contemporary in

his writings or reflect Botticelli’s works in his own. In fact, Botticelli’s

Annunciation fresco of 1481, then in the loggia of the church of San

Martino alla Scala (now in the Uffizi), is most likely the target of some

of Leonardo’s harshest criticism:

I recently saw an Annunciation in which the angel looked

as if she wished to chase Our Lady out of the room, with

movement of such violence that she might have been a

hated enemy; and Our Lady seemed in such despair that

she was about to throw herself out of the window.

He took another, unambiguous, swipe at Botticelli in his unpub-

lished Treatise on Painting (Trattato della Pittura) when advocating that

artists should throw sponges loaded with paint at walls and study the

99

100 The Young Leonardo

resulting abstract stains, which might suggest landscapes, battles, and

other images that could stimulate the imagination:

– Botticelli said that such study [of wall stains] was in vain.

[But] it is really true that various invenzioni [inventions or

ideas] are seen in such a stain. I say that a man should

look into it and find heads of men, diverse animals, battles,

rocks, seas, clouds, woods, and similar things, and note

how like it is to the sound of bells, in which you can hear

whatever you like. But although those stains will give you

invenzioni they will not teach you to finish any detail. This

painter of whom I have spoken makes very dull landscapes.

One also finds in Leonardo’s manuscripts the occasional, grumbling

remark that seems to be part of a reticent, one-sided dialogue between

him and Botticelli, comments that were probably rhetorical and never

actually communicated but suggest that he had Botticelli on his mind.

Apparently, for Leonardo, there was an emotional dynamic, or irritant,

where his colleague was concerned.

Even if a “healthy” rivalry with Botticelli did exist, Leonardo

would have feared boredom much more than the competition. His

greatest professional shortcoming was that once he had solved an

artistic problem, in his drawings or in his mind, he wished to move

on, lacking the patience to commit to it to paint or, in some cases,

paralyzed by his own perfectionism. What had been a bad habit of

leaving pictures unfinished in the Verrocchio’s shop seems to have

become almost a pathology for Leonardo. He famously wrote with

exasperation, probably self-inflicted, on more than one manuscript

page, “Tell me if anything was ever done.”

Although his brush sometimes faltered, his pen never ceased to

convey the entire range of human experience and expression. In the

same period that he celebrated those intimate, affectionate moments of

familial life in his Madonna studies, he objectively recorded mankind’s

public brutalities on other sheets. With dispassionate precision, he

drew the hanged corpse of the savage Bernardo di Bandino Baroncelli,

one of the Pazzi family conspirators, who had murdered the young

Giuliano de’ Medici at high mass in Florence cathedral in late April

1478 (fig. 41). The Pazzi – banking, business, and political archrivals

of the Medici – had been incensed by Lorenzo’s efforts to curtail their

power. Reportedly, Baroncelli delivered the first, probably fatal, blow

15. Leonardo, the Medici, and Public Executions 101

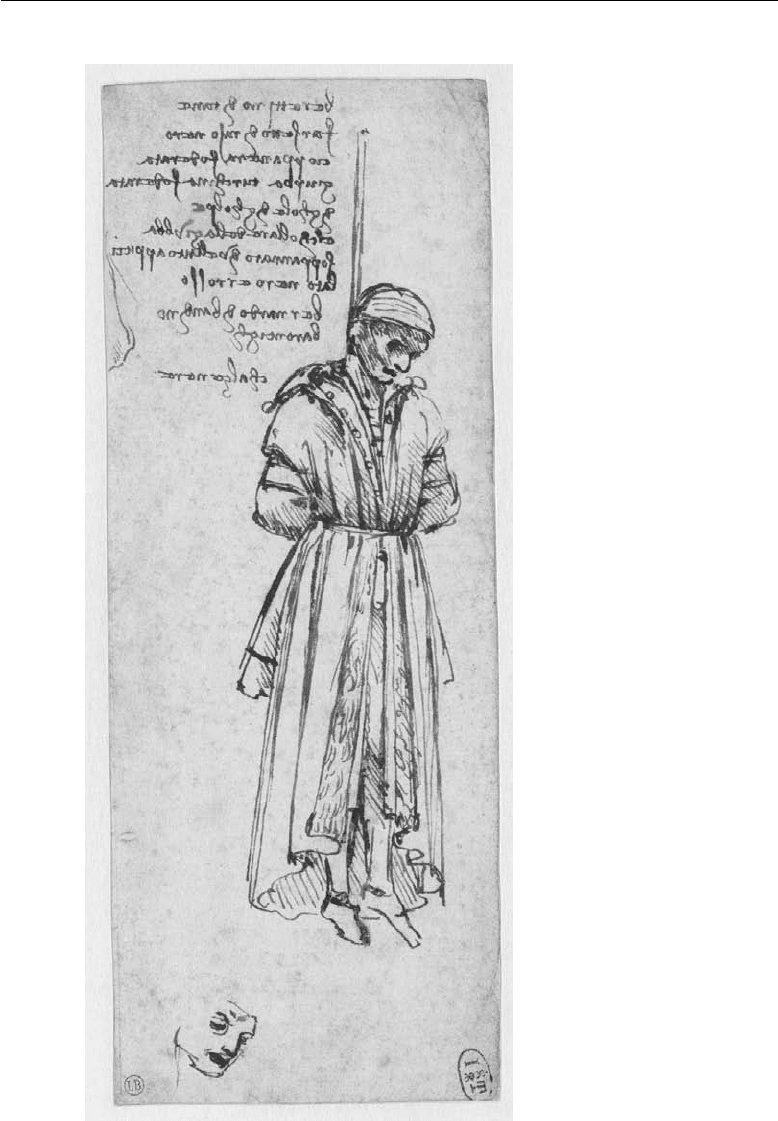

Figure 41.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies of the Hanged

Bernardo di Bandino

Baroncelli, 1479,penand

ink, Bayonne, Mus

´

ee

Bonnat. R

´

eunion des

Mus

´

ees Nationaux/Art

Resource, NY.

102 The Young Leonardo

to Giuliano’s chest, and then buried a long knife in the stomach of the

Medici bank manager Francesco Nori, killing him, when he moved

to defend his boss, Lorenzo de’ Medici. Others tore at Giuliano with

daggers. Lorenzo, the primary target of the plot, miraculously escaped

with just a minor neck wound, after being attacked by two priests who

were in on the scheme. The clerics were quickly caught, castrated,

and hanged.

The assassination attempt came after Lorenzo, more concerned

with cultural matters than military affairs, had squandered much of

the Medici reputation for toughness – and appeared to many to be

weak himself. His habit of quickly surrendering “protection” money

to any who threatened him or the city was seen as indicative of his

vulnerability and general fearfulness. His constant struggle with gout,

the “Medici disease,” as well as his high-pitched, nasal voice, often

caused him to seem less than virile and commanding.

To reassure the Florentine public of his survival, Lorenzo appeared

several times after the assault in the windows of the Palazzo Medici.

Wishing to reinforce that message, some of his relatives and supporters

commissioned three wax effigies of him, two of which were placed

in prominent places in the city (the third was sent to Assisi). Perhaps

accompanied by Leonardo, Verrocchio oversaw the fabrication, by

his friend, the wax-worker Orsino Benintendi, of these sculptures,

painted with natural colors to appear as lifelike as possible. They

portrayed Lorenzo bandaged and wounded, as he appeared hours after

the attack, or wearing the apparel of the average Florentine citizen.

We can assume that the effigies were rather convincing. Florence,

and Orsino especially, were renowned for such figures and other wax

simulacra.

The assassin Baroncelli, a well-connected member of another old

Florentine banking family, managed to escape to Constantinople, from

where the Turkish Sultan finally agreed to extradite him in late 1479.

Leonardo made his quick sketch at the end of December, when the

murderer was hanged, together with his wife, from windows of the

Palazzo del Capitano, on the same busy street as Ser Piero’s house.

Although public executions were common in late-fifteenth-century

Florence, occurring at a rate of more than one a week, they were

usually performed in a designated field on the outskirts of the city,

rather than in a central square, a venue reserved for high-profile

criminals. Most of the offenders, as many as fifteen at a time, were

15. Leonardo, the Medici, and Public Executions 103

led out through the eastern part of the city, past the church of Santa

Croce, to the gallows by way of the via de’ Malcontenti (Street of the

Malcontents) – so-named because many individuals were sentenced

to death for allegedly conspiring against aristocratic families. This fre-

quent recourse to capital punishment necessitated special, communal

heralds on horseback, who regularly announced captures, death sen-

tences, and dates of execution. Such brutal and public spectacles hardly

deterred the roiling lawlessness of the city. But they did afford drawing

practice to Leonardo, who, according to the Milanese art theorist and

painter Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, closely studied the gestures of the

condemned, so that he could “delineate the tension in their brows,

and the expressions of their eyes and whole appearance.”

Leonardo’s sketch of the deceased Baroncelli includes a second,

detailed rendering of the face and, alongside the body, a careful

description of the colors of his clothes: “small tan-colored cap, black

satin doublet, black-lined jerkin, blue coat lined with black and white

velvet stripes – black hose.” The artist probably made these inscrip-

tions to aid his memory if he were later assigned to create a painting

of Baroncelli on the wall of the Podest

`

a (or Bargello), the city court

and jail, on which effigies of the other principal conspirators had

been rendered a year earlier. It was a Florentine tradition to paint

such murals as posthumous defamations of offenders and as warnings

to enemies, after the actual corpses had deteriorated or been hacked

apart.

In 1478, Botticelli had been hired by the Ottimati (the Florentine

government’s council of eight “best men”) to paint several of the Pazzi

conspirators as they dangled, upside-down, from the windows of the

Podest

`

a, and Lorenzo himself had written verses to go underneath

their heads. These images flanked others that Andrea del Castagno

had created decades earlier, in 1440, when he was assigned to portray,

also inverted, eight traitorous members of the old Florentine Albizzi

family, who had been executed for joining forces with the Milanese at

the Battle of Anghiari. Leonardo saw the faded remnants of all these

effigies (erased only in 1494) every time he visited his father in his

Podest

`

a office. It may have occurred to him that he could perhaps

gain favor with the Medici by following in the footsteps of Castagno

(known as Andreino degli Impicchati – Little Andy of the Hanged Men),

who, as a farmer’s son from the Mugello region of Tuscany, rose from

a similar, rural background to attain high status and fame.

104 The Young Leonardo

It appears, however, that, despite his preparations, Leonardo was

never asked to add a nature morte of Baroncelli to the wall of shame.

The de facto leader of the Florentine Republic and victim of the

conspiracy, Lorenzo was not present to sanction it. As it happens, he

was just then arriving in Naples, on a critical diplomatic mission that

would last many months. Further, the Ottimati and Medici loyalists

may have decided that they had in their hands a more effective tool

for defamation; with the printing press, newly arrived and established

by Bernardo Cennini in Florence in 1477, the writer Poliziano and

others were able widely to disseminate accounts of the Pazzi plot and

of the conspirators’ treachery. Although his act of artistic vengeance

was never realized, Leonardo must have still taken some consolation

in knowing that Giuliano had found pleasure in the joust standard he

had helped create, which now rested unobserved, beside Botticelli’s

mounted pennant, Verrocchio’s prize helmet, crested shields, and

other souvenirs in the young man’s abandoned trophy room.

16. Leonardo and Ginevra de’ Benci

L

eonardo finally had the opportunity in this period to

test his hand at portraiture – of a more benevolent kind –

when he was engaged to paint a likeness of the lovely Ginevra de’

Benci, the sophisticated daughter of the wealthy banker, Amerigo

de’ Benci, and an object of admiration for numerous poets (fig. 42).

Leonardo’s father may have facilitated the commission; a longtime

friend of the Benci family, he drafted many legal documents for them

over the years. Although married in 1474 toLuigidiBernardoNicco-

lini, the precocious, sharp-witted Ginevra attracted the fervid atten-

tion of the Venetian ambassador Bernardo Bembo, when he visited

Florence later in the decade. The intellectual Bembo’s devotion to her

reportedly took the form of a chaste “Platonic love,” a term coined at

that time by Ficino. Openly and widely acknowledged, their relation-

ship (and her beauty) became the subject of Petrarchan sonnets writ-

ten by several poets at the Medici court, notably Cristoforo Landino,

Alessandro Braccesi, and Il Magnifico himself.

The device or impresa on the reverse of her portrait, Bembo’s

heraldic laurel and palm, attests to the closeness of their bond – and

very probably indicates that he was the patron (fig. 43). If Bembo

commissioned the picture (with Benci approval) – as a gift to Ginevra

or remembrance of her – he likely would have done so during his

extended second sojourn in Florence, from July 1478 to May 1480,

after he had known her for some time, rather than during his first

mission there from January 1475 to April 1476; some stylistic aspects

of the picture would seem to suggest this as well. If, as some have

maintained, the portrait had been ordered by her husband, Luigi, she

almost certainly would have been depicted wearing the ritual jewelry

that he had bestowed on her, symbols of their union and of his wealth.

105

106 The Young Leonardo

Figure 42.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Portrait of Ginevra de’

Benci,c.1478–80,oil

on panel, Washington,

National Gallery of

Art. Image courtesy of

the Board of Trustees,

National Gallery of Art,

Washington.

This display of the groom’s “dowry” was of no small significance,

for its magnitude determined the very plausibility and viability of a

marriage in mercantile Florence. In the fifteenth century, one kept

a large portion of one’s savings in jewelry and clothes (as well as in

communal/municipal bonds) rather than in cash. Instead, her costume

features no jewelry but a black scarf, which may have been a sign

of affiliation with the Platonic academicians; Landino is represented

wearing a similar, academic stole in a Ghirlandaio fresco.

In its otherwise showy artifice, Leonardo’s portrayal of Ginevra,

at the age of twenty or twenty-one, was probably intended to be

the visual equivalent of metaphors employed by Medici poets. In

one sonnet, Landino effusively describes her “hair of gold,” “ivory

teeth, white as snow,” “swan’s neck,” and “golden nipples” on “snowy

bosom.” Leonardo’s picture generally conforms to Landino’s meta-

phorical excesses, showing necessary decorum, however, as regards