Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

19. The Madonna Litta 127

as the Mona Lisa, which he lugged to France and, probably, to Rome,

he apparently used the works as “display samples,” to demonstrate his

abilities to prospective clients.

Over the years, Leonardo scholars have fiercely debated whether

the Madonna Litta should be assigned to the master or his pupil. How-

ever, the uninspired essays in landscape and costume, as well as the

evenly “licked” finish of the picture, surely betray an inferior hand.

Whereas Leonardo’s shadows always appear to be gently wafted over

the surfaces of flesh and fabric, here they are regularized and have the

aspect of a stain. Despite this extensive intervention of an assistant, the

general design of the picture and, especially, the complicated, twisting

pose of the Christ Child must be attributed to the master. Leonardo

also would have stipulated the inclusion of the symbolic goldfinch,

cozily and ominously tucked into the breach between mother and

child.

20. The Adoration of the Magi

and Invention of the

High Renaissance Style

P

roba bly tha nks to his father once ag ain , leonardo

obtained a commission in 1481 to paint an Adoration of the

Magi for the monastic church of S. Donato a Scopeto, outside of

Florence (fig. 54). Certainly, the odd financial circumstances of the

project point to Ser Piero’s notarial involvement; a saddle manufac-

turer bequeathed to S. Donato an endowment for a painting for the

high altar and at the same time left a dowry for his granddaugh-

ter. The scrupulous Ser Piero would have foolishly staked his good

name and standing, as the official notary of the patrons, in rec-

ommending his brilliant but unreliable son for the job. Ser Piero’s

tax records may be relevant. These indicate that he had moved

with a new (fourth) wife to a house on the via Ghibellina and

had stopped supporting Leonardo financially by 1480 – a reason-

able decision in light of Leonardo’s age (twenty-seven or twenty-

eight) and the fact that Ser Piero had two other legitimate children

to look after. Almost predictably, Leonardo’s work on the monu-

mental panel was left incomplete; he never progressed beyond the

underpaint stage. Nevertheless, even in its unfinished state, the pic-

ture must be considered a conceptual masterpiece, and the many

extant studies for the work reveal the enormous amount of energy –

in concentrated and original thought – that Leonardo devoted to the

composition.

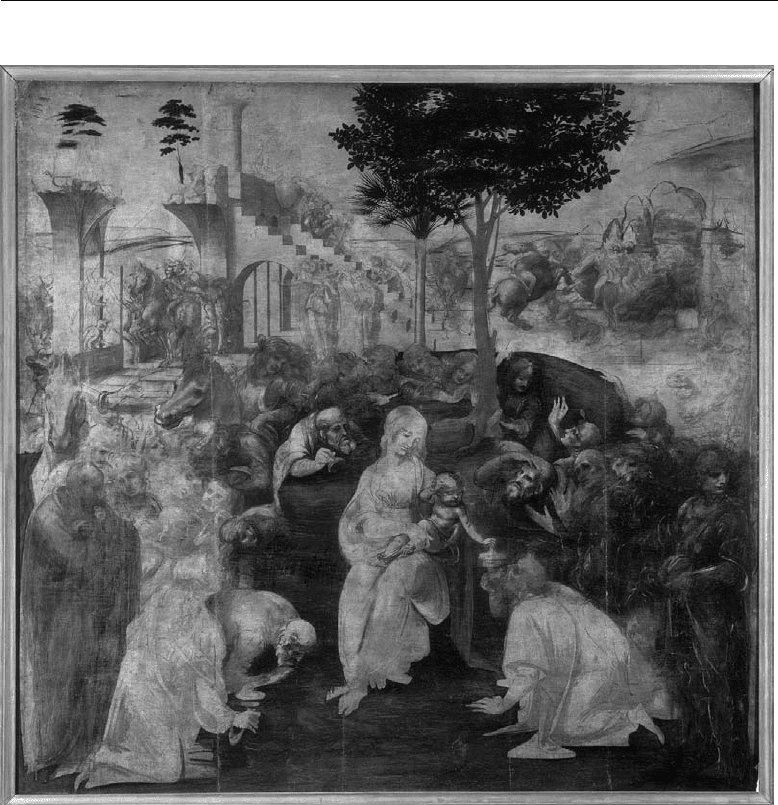

Representing both the beginning and epitome of the High Renais-

sance style in Florence, the picture is painstakingly composed so that

every element – every figure, every gesture, and every symbol – con-

tributes dynamically to the meaning of the work. Leonardo believed

that, as in nature, form must perfectly follow function: style should

be exactly appropriate to content, no actor and no action unnecessary

129

130 The Young Leonardo

or redundant, each gesture the most compelling manifestation of an

emotion. He once wrote:

Every smallest detail has a function and must be rigor-

ously explained in functional terms that are in accord with

nature as opposed to the postulates of the ancients. Human

ingenuity – will never discover any inventions more

beautiful, more appropriate or more direct than nature,

because in her inventions nothing is lacking and nothing is

superfluous.

Just as the Munich and Benois Madonnas concerned the themes

of sight and insight, his carefully conceived Adoration of the Magi is

spatially organized according to the perceptions of the actors and their

degree of enlightenment. The three Magi, who recognize the infant

as the Savior, form a compact triangle with the Virgin and Child

on the surface, or picture plane, of the painting. Meanwhile, those

actors that have an instinctive but unspecified awareness of the child’s

divinity create a semicircle, excavating a shallow space, around the

triangle. Some appear disoriented; others seem blindly to gaze, eyes

shielded, into a bright light. The heroic figures at each corner of the

composition search for answers to explain this mysterious spiritual

presence: the older man or seer at far left, in deep contemplation,

looks within – as those around him seek his wisdom; his counterpart,

the young man at right, possessing less knowledge of the world, looks

without – beyond even the universe of the picture.

To the right of center, a man recoils, hand raised, as a young

tree miraculously springs from age-old stone, a double allusion to the

wooden cross on Golgotha and the new spiritual life on earth under

Christ, rooted in the Old Testament bedrock of the Jews. Removed

from the sacred knowledge and geometry of the lower half of the

composition, the small, combative, background figures coexist within

a discrete and mathematically generated, perspective space, unobser-

vant and wholly ignorant of the historical event before them. The

themes to which Leonardo alluded in his early Madonnas now serve,

in a brilliant summation, to integrate the entire structure and narrative

of the work.

When such a lucid articulation and equilibrium are attained in a

pictorial scheme, a painting is sometimes said to be “classical.” That is,

the work recalls, in a general sense, the consummately calm sculptures

of fifth-century (b.c.) Athens, such as Myron’s Discus Thrower or the

20. The Adoration of the Magi and Invention of the High Renaissance Style 131

Figure 54.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Adoration of the Magi,

1481, oil on panel, for

S. Donato a Scopeto,

now Florence, Uffizi.

Alinari/Art Resource,

NY.

metope reliefs of the Parthenon, in which difficult poses effortlessly

find balance and opposing forces are resolved or suavely contained

within a rational, geometric framework. However, Leonardo’s classi-

cism is not a recollection but a parallel development – the result of

similar intentions rather than imitation. For during his early years in

Florence, his access to the vocabulary of antique art, like his access

to Greek and Latin, was extremely limited. Whereas Lorenzo the

Magnificent possessed a respectable collection of ancient coins and

carved gems, he apparently had only about half a dozen significant

antique sculptures. These works – the mythological figures of Marsyas

and Priapus,aBoy with a Bird, marble busts of the Roman emper-

ors Agrippa and Augustus, and a bronze Head of a Horse –werefar

different in spirit from “classical” fifth-century Greek sculpture and

132 The Young Leonardo

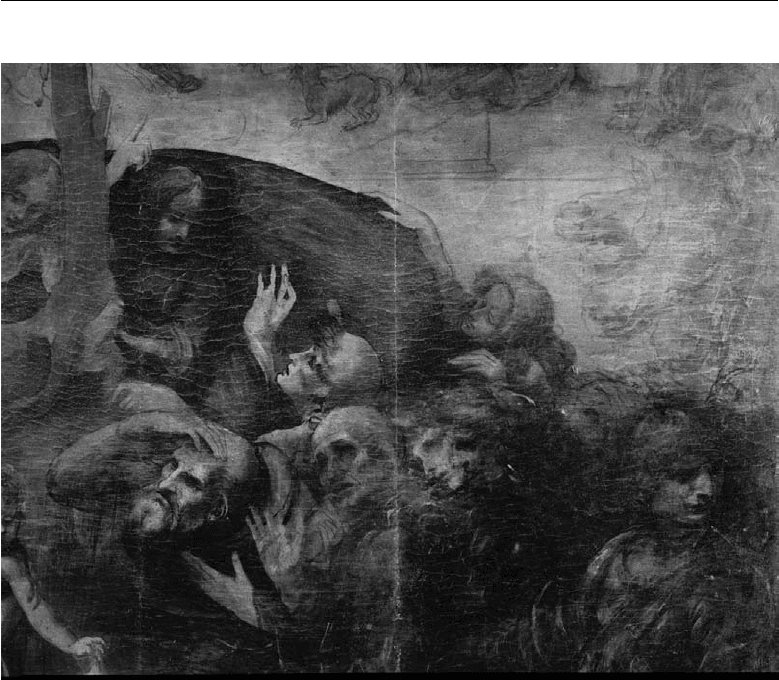

Figure 55.

Detail of Figures

to the Right of the

Virgin and Child in

Adoration of the Magi,

fig. 54. Erich Lessing/

Art Resource, NY.

provided, at any rate, only sparse and fragmentary examples for study.

The serene poise and restrained energy of the ancient Greek master-

pieces of Myron, Phidias, or Polykleitos, which Leonardo’s art evokes,

were completely unknown to him.

Although not obvious on first inspection, Leonardo’s point of

departure for the Adoration was once again the Pollaiuoli Shooting of

Saint Sebastian (fig. 23). From that picture, he derived the notion of

dividing the painting into two realms of action: a triangle of figures in

the foreground bounded by a dark semicircle and a distant panorama

of horsemen linked, in their linear dispersal, to the horizon. Following

the Pollaiuoli, Leonardo placed a tree at center, surrounded by figures

that mirror one another’s poses (a much-renowned feature of the

brothers’ picture), with grand classical ruins in the left distance, and a

rocky outcropping in the background at right. However, as we have

seen, he elaborated extensively on this framework, infusing each figure

with an individual personality and motivation and creating an entirely

new, compositional and symbolic cohesiveness.

20. The Adoration of the Magi and Invention of the High Renaissance Style 133

Figure 56.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies for the Adoration

of the Magi, 1481,pen

and ink, Paris, Bib-

lioth

`

eque de l’Ecole

Nationale Sup

´

erieure

desBeaux-Arts(424).

Photo: Jean-Michel

Lapelezie.

The profound thought that Leonardo devoted to each actor is evi-

dent not only in the two standing “prophets,” as they are sometimes

called, on either side of the composition, but even in the more sum-

marily realized figures of the inner circle. To the immediate right of

the Christ Child, a trio of heads sensitively conveys a spectrum of emo-

tions: quizzical irritation, fearfulness, and hesitant curiosity (fig. 55).

Opposite them, a befuddled Saint Joseph cautiously peers from behind

a rock over Mary’s (proper) right shoulder. He holds the lid to the

jar given to Christ by the elder magus, Melchior, who kneels directly

below, touching his face to the ground, as if weighted down, humbled,

by his full knowledge of the child’s identity. Behind Joseph, two beau-

tiful, vacuous youths who have just ridden in from the background

(sitting, indecorously, in intimate tandem on their horse) inquire cav-

alierly about the foreground gathering; the man whom they consult

points to the miraculous, robust tree that grows from solid rock. The

three young men closest to the tree appear celebratory: the youth

on the right indicates, with finger raised heavenward, that the newly

sprouted tree is the work of God; beside him, another man places his

cupped hands before the tree in a gesture denoting worship as much

as surprise; the youth farthest to the left, stationed behind the Virgin

134 The Young Leonardo

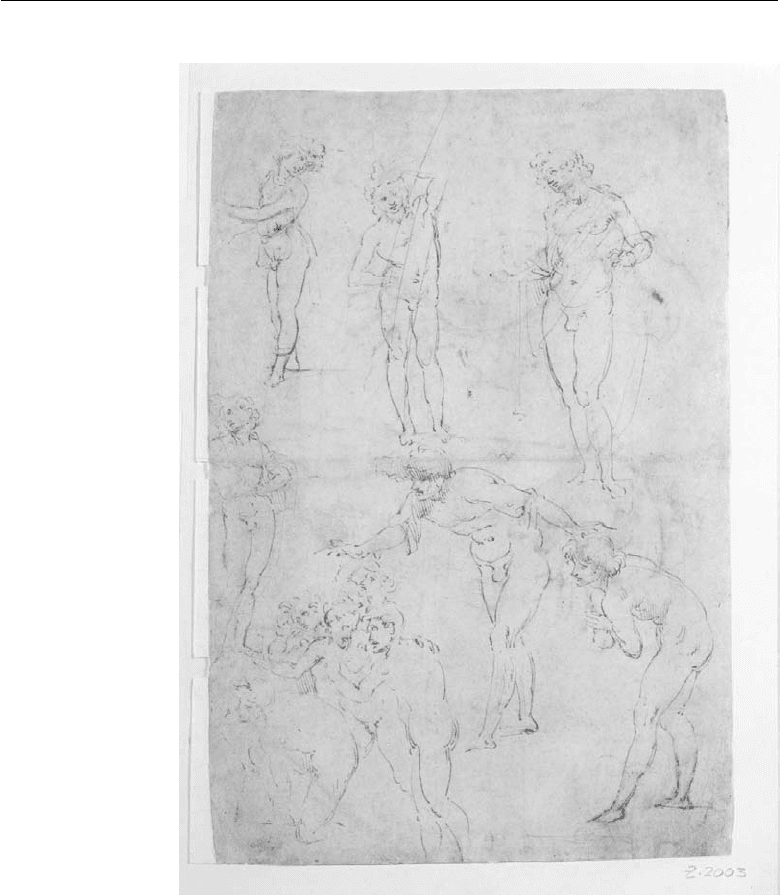

Figure 57.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Figure Studies for the

Adoration of the Magi,

1481,penandink,

Cologne, Wallraf-

Richartz Museum,

Graphische Sammlung,

no. Z 2003. Collection

of Wallraf-Richartz

Museum, Rheinisches

Bildarchiv K

¨

oln.

and Child and directly in front of the distant palm, an ancient symbol

of victory over death or of resurrection, looks knowingly toward the

viewer.

Leonardo’s many preliminary studies in pen and ink reveal how

much he fretted over the expressions and gestures of all these figures.

In sheets preserved in Paris and London, one can see how carefully he

considered the attitude of the old “prophet” at left. On the Paris sheet

(fig. 56), he drew the brooding figure, first as a young man both with

and without a staff. He tried both possibilities again in his series of

studies in London, arriving at a figure that approximates the old seer

of the painting in gravity of stature and thought. Interspersed among

20. The Adoration of the Magi and Invention of the High Renaissance Style 135

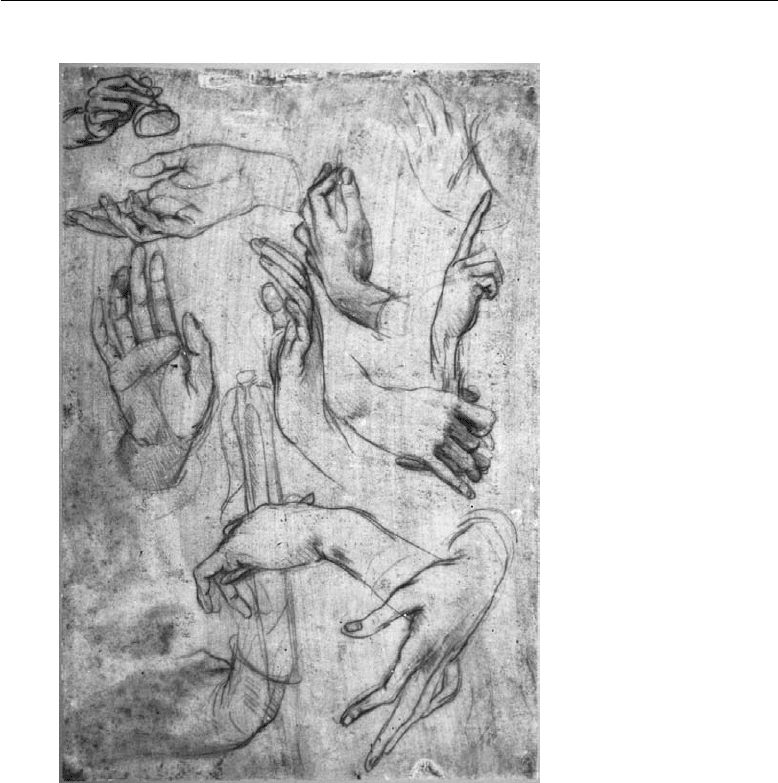

Figure 58.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies of Hands for the

Adoration of the Magi,

1481,metalpoint,

Windsor Castle, Royal

Library (12616). The

Royal Collection

C

2010 Her Majesty

Queen Elizabeth II.

these sketches are his ideas for numerous other witnesses, generally

more animated and upright than those he would choose to populate

the foreground of the Uffizi picture – presumably deciding in the end

that if the ancillary figures were too busy and prominent, they might

distract from the principal drama. For those figures in the painting

that bow and genuflect in wonder before the Holy Family, Leonardo

looked to the varied studies he had made on two sheets now preserved

in Cologne and the Louvre (fig. 57). The extensive repertoire of

poses on these pages affords us a tantalizing glimpse of the obsequious

choreography of Renaissance court manners. Leonardo also created

a number of studies of elegantly expressive hands for the Adoration

on a double-sided sheet at Windsor Castle (fig. 58). He would review

these and make many more “talking-hand” drawings when, more than

a dozen years later, he composed his Last Supper for Santa Maria delle

Grazie in Milan. His fluency in the language of hands was, perhaps,

136 The Young Leonardo

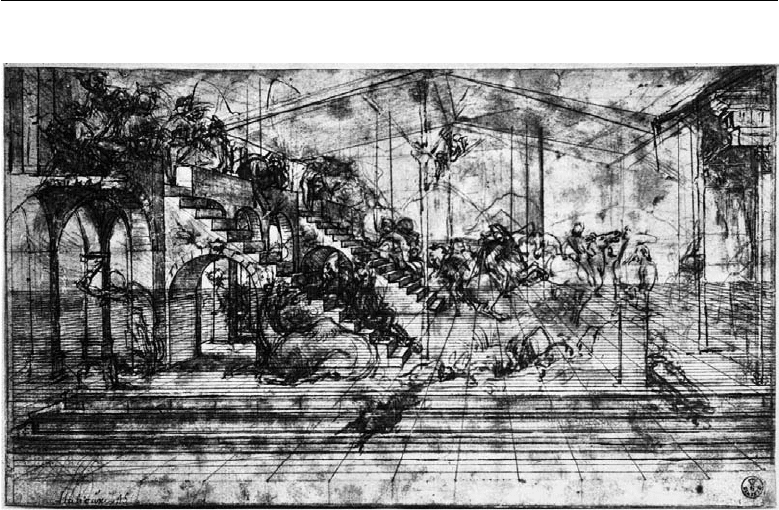

Figure 59.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Perspective Study for Back-

ground of the Adoration of

the Magi, 1481,metal-

point, pen and ink with

wash, Florence, Uffizi

(436E). Alinari/Art

Resource, NY.

due in part to his scrutiny of the gestures of the deaf, a practice he

recommended to other artists in his Treatise on Painting.

As we have observed, Leonardo conceived the distant background

figures of the Adoration of the Magi as inhabitants of an independent

realm, with its own internal perspective or spatial logic and velocity

of activity. To this end, he actually created a large, independent, com-

positional study for the background scene, rendered with a fastidious

linear grid, which is still extant and in the Uffizi’s collection (fig. 59).

Untouched by Christ’s grace and subject to mundane, physical laws,

the figures of this separate, ancient world move about impulsively and

frantically, compelled by their bestial nature – running, clashing, nois-

ily blowing horns of alarm. As in the painting, they embody centuries

past of spasmodic, pointless conflict. The stairs of their temple lead

nowhere. Leonardo here seems to have improvised and expanded on

the traditional ruins motif in Italian paintings of the Adoration and

Nativity, in which the remnants of ancient buildings allude to the Old

Dispensation of the Jews, on which Christ will build his church. This

architectural symbolism was probably inspired by the biblical refer-

ence, in Isaiah (9:10), to the coming of the messiah: “the bricks have

fallen, but we will build with dressed stones.”

A few of the actors in Leonardo’s drawing try, unsuccessfully, to

control frightened horses, a Platonic metaphor for restraint of the