Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

23. Early Ideas for the Last Supper 157

from top to bottom, rather than in a circulatory loop. Unfortunately

for the artist, a true understanding of the circulatory system, and the

functions of the heart, would not be attained until the seventeenth

century, with the empirical research of the English physician William

Harvey.

24. Leonardo and

the Saint Sebastian

C

losely related in st yle to the ea rly LAST SUPPER and

Adoration of the Magi studies and so, presumably, from the same

period (c. 1480–81) are a couple of small but vital drawings that

Leonardo made of Saint Sebastian, now preserved in Bayonne and

Hamburg (figs. 69 and 70). The black chalk sketch in Bayonne would

seem to be the earlier of the two studies; the frontal stance of the saint

there is repeated faintly in leadpoint in the Hamburg sheet, where it

serves as a starting point for further elaboration in wiry ink contours.

Although his extant studies are few and no painted Sebastians by him

survive, Leonardo seems to have become somewhat preoccupied with

the saint during his first Florentine period. The list he drew up of

his artistic possessions around 1482, shortly after settling in Milan,

mentions eight drawings of the saint.

According to legend, Sebastian was an officer of the Praetorian

Guard under the Roman emperor Diocletian in the third century.

He was ordered to be shot with arrows when he was discovered to

be secretly Christian. The popular subject would have been especially

attractive to Leonardo, as it was to other Renaissance artists, because

it afforded the opportunity to portray a full-length, standing male,

nearly nude. Images of Sebastian, who miraculously recovered from his

wounds, were almost always in demand due to the centuries-old belief

that he was a protector against plague, alleged in ancient times to be

caused by the arrows of the Greek god Apollo. Leonardo’s designs may

have been intended either for small-scale, private devotional paintings

or for ex-votos, pictures made in gratitude for deliverance from the

disease. Plague raged throughout Europe between 1478 and 1480,

and in late 1479, there was a devastating outbreak in Florence, which

159

160 The Young Leonardo

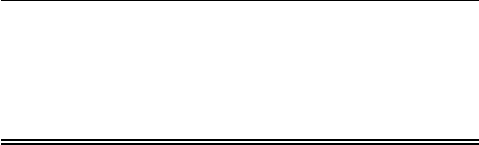

Figure 69.

Leonardo da Vinci,

St. Sebastian,

c. 1480–81, black chalk,

Bayonne, Mus

´

ee Bonnat

(1211). R

´

eunion des

Mus

´

ees Nationaux/Art

Resource, NY.

24. Leonardo and the Saint Sebastian 161

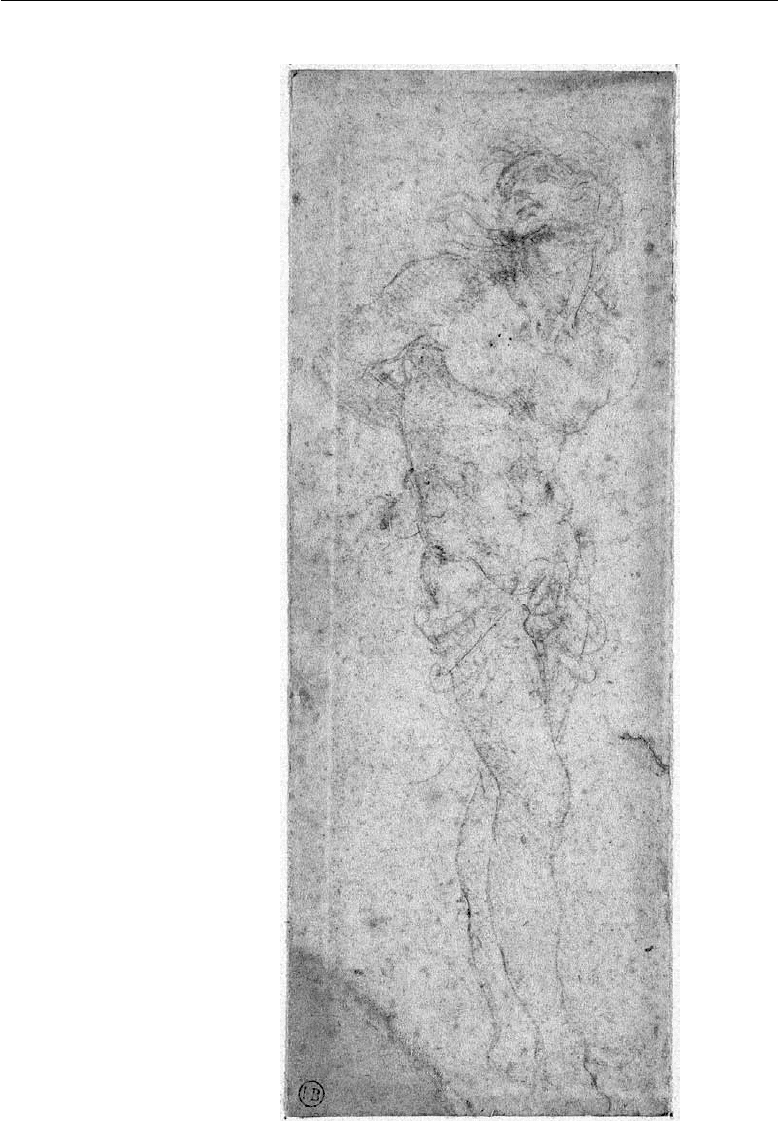

Figure 70.

Leonardo da Vinci,

St. Sebastian Tied to a

Tr ee ,c.1480–81,pen

and ink over leadpoint,

Hamburg, Kunsthalle

(21489). Bildarchiv

Preussischer Kulturbe-

sitz/Art Resource,

NY.

closed down workshops and took the lives of more than 20,000 people,

most buried in the cemetery of the hospital of San Martino della

Scala, including Verrocchio’s onetime master and friend, the sculptor

Antonio Rossellino and his two young sons.

162 The Young Leonardo

No doubt, when Leonardo made his sketches, the painted Saint

Sebastians of the Pollaiuoli (fig. 23) and Botticelli (then in the church

of Santa Maria Maggiore) were in the back of his mind. However, the

tilted-back head and forked tree of Leonardo’s drawings suggest that,

paying private homage, he may have consulted as well the marble Saint

Sebastian (c. 1476–78) in the nearby town of Empoli by the respected

Rossellino – a tiny man with grand talents. Perhaps Rossellino’s mas-

terpiece, this life-sized Sebastian showed his prescient and profound

assimilation of Hellenistic Greek sculpture, offering an authoritative

model for those with similar ambitions.

Whatever his immediate sources, Leonardo obviously found the

usual, frontal pose of the saint wanting, and so experimented with at

least three other positions, twisting the head and legs in opposition to

the torso. In wishing to convey the saint’s struggle, the artist probably

looked for ideas to Lorenzo the Magnificent’s two prized, antique

sculptures of the satyr Marsyas bound to a tree. Although both sculp-

tures are lost, we know from written descriptions, other versions of

the works, sketches, and carved gems that one of these (inherited from

Cosimo) was a “hanging” Marsyas type, with arms fastened high on a

tree, and the other was “seated” – more leaning – against a tree trunk,

with legs bent and swiveled together to one side, similar to those of

the Hamburg Sebastian. Leonardo would have watched when Verroc-

chio, at the request of Lorenzo (who had acquired the piece himself),

restored and completed the fragmentary “seated Marsyas,” carving and

attaching new legs and arms, perhaps in 1477 or 1478. The stunning,

repaired Marsyas, realized in “stone the color of blood” with natural

white veins that simulated those of human flesh, must have made a

powerful impression on the young artist. So inspired, Leonardo much

enlivened his saint, arriving at the extreme, spiraling form of contrap-

posto, or counterpoise of limbs and weight, that would come to be

ubiquitous in the next century and celebrated – or condemned – as

the figura serpentinata, or serpentine figure.

25. Saint Jerome

W

hen leon a rdo , in the wa ning years of the pla gue,

depicted another extremely popular male saint, the peni-

tent Jerome in the wilderness (fig. 71), he employed what is sometimes

called the “dark manner” of the Adoration of the Magi, where light

forms emerge from a tenebrous background. His powerful painting of

c. 1480–82, now in the Vatican, is probably contemporaneous with the

Adoration and was left in a similarly unfinished state. The Saint Jerome

may have been intended for the Benedictine church and religious

complex of La Badia in Florence, another long-standing institutional

client of Leonardo’s father. Perhaps not coincidentally, Filippino Lippi

supplied the monks there with a painting of the subject in the later

1480s; Lippi, it should be recalled, had earlier fulfilled Leonardo’s

abandoned commissions for the Palazzo della Signoria and S. Donato

a Scopeto.

At a certain point, Leonardo may have begun to recommend Lippi

for projects that he was unable to complete. As his works attest, the

younger artist well understood and sought to emulate the older master’s

innovations. Lippi’s compositional drawings show his desire to achieve

the intricate, comprehensive unity of Leonardo’s Adoration, and his

Badia Saint Jerome is reminiscent of the Vatican work. Leonardo must

have admired his abilities (and appreciated his imitation) and, perhaps,

felt a special bond with an artist who was similarly defined by his

illegitimate birth. Lippi, on at least one occasion, apparently tried to

reciprocate Leonardo’s goodwill and generosity, when, in 1500,he

asked him to take over a commission for an altarpiece for the church

of SS. Annunziata, a double-sided panel with a Deposition from the Cross

on the front and an Assumption of the Virgin on the back. (Reverting to

the usual pattern, Leonardo, for unknown reasons, aborted the project,

163

164 The Young Leonardo

and several years later, Lippi executed the Deposition and Perugino the

Assunta.)

Aside from having coined the cautionary phrase “avoid like the

plague,” Saint Jerome was not, like Sebastian, associated with the dis-

ease. Nevertheless, Leonardo’s painting of the nobly suffering Jerome

would have offered some consolation and encouragement to febrile

victims of the illness. According to his letters, as a young person,

Jerome had retired for four years to the Syrian desert. There, after

a while, the severe heat, asceticism, and deprivation caused him to

experience vivid sexual hallucinations and intense lust, which he tried

to dispel by beating his chest. In his strength of will and reason, he

became an exemplar for the Benedictines and other monastic orders.

The Golden Legend, the apocryphal compilation of saints’ lives, relates

that during his retreat the compassionate, if crazed, Jerome also pulled

a thorn from the paw of a lion, thereafter his devoted companion

in the wilderness. Leonardo was faithful to the scene and conditions

described in Jerome’s vivid letters:

in that vast solitude which is scorched by the sun’s heat

and affords a savage habitation for monks – whenever I saw

some deep valley, some rugged mountain, some precipitous

crags, it was this I made my place of prayer, my place of

punishment for the wretched flesh. – My face was pale

from fasting, and my mind was as hot with desire in a

body cold as ice. Though my flesh, before its tenant, was

already as good as dead, the fires of passion kept boiling

within me.

Reacting to unseen powers, Leonardo’s lion roars as the emaciated

saint strikes his chest with a rock to drive out his own bestial and

carnal spirits. In one of his moralizing tracts on animals, Leonardo

wrote that, at the sound of a lion’s roar, “Evil flees away, shunning those

who are virtuous.” During the day, the artist would have observed and

drawn the Florentine pride of lions (symbols and mascots of the city)

stretching in their cages behind the Palazzo della Signoria. On most

evenings, he would have heard their ferocious sounds when he visited

his father’s house on the via Ghibellina.

Situated in the most isolated and barren wilderness imaginable, the

penitent Jerome beseeches God, to whom he bows in courtly fashion,

to witness his act of contrition. The vantage point of the picture, which

25. Saint Jerome 165

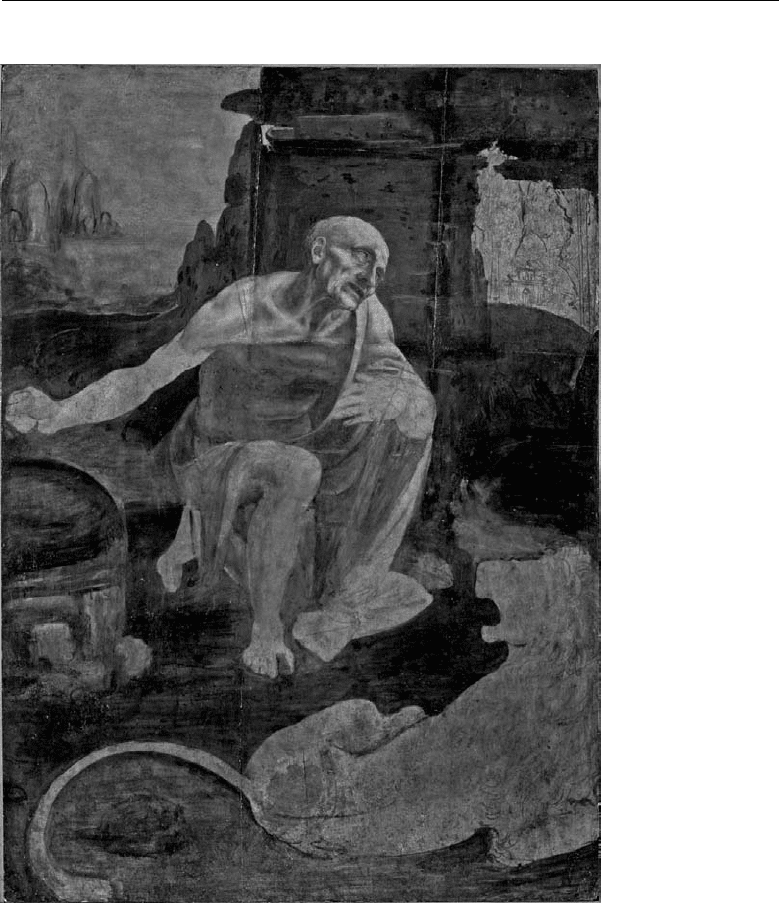

Figure 71.

Leonardo da Vinci, Saint

Jerome in the Wilderness,

c. 1480–82,oilon

panel, Vatican, Musei

e Gallerie Pontificie.

Scala/Art Resource,

NY.

implies that the viewer is on the ground before the self-humbled saint,

is unprecedented, as is our direct access to his private meditation. At

the same time, Leonardo establishes rapport, compositionally, between

the saint and the lion through their complementary arabesques, as well

as a visual analogy between the saint, seemingly excavated from stone

rather than painted, and the background rocks, traditional symbols of

endurance and faith. Although this latter connection is inadvertently

reinforced by the monochromatic, incomplete state of the picture,

it nonetheless points to Leonardo’s tendency to analogize, a way of

166 The Young Leonardo

thinking that caused him to associate cloth folds and hair growth with

the movement of water, human veins with the root systems of plants,

and human faces and temperaments with those of animals.

Although out-of-doors, Jerome is oddly trapped within a confined

space, bounded by stone formations, a metaphor for his emotional

isolation and spiritual predicament. The looming rock arch behind

him is crudely suggestive of a tomb, and the round structure to his

immediate left vaguely resembles a well or baptismal font. (Some-

what counterintuitively, in the Bible, wells are commonly located in

the wilderness, as in Genesis 16:14.) If the painting were finished,

these features might less ambiguously allude to the themes of death,

ablution, and rebirth, and the small church, just faintly sketched in

the right distance, where the rocks open to the light, would more

clearly indicate the path to redemption. The building, redolent of

architectural designs by Alberti, also serves to remind the viewer of

the intellectual Jerome’s divine calling, through Pope Damasus, to put

“the offices of the Church in order,” as a church leader and admin-

istrator. He became one of the four fathers of the Western Church,

settling in the year 386 in Bethlehem, where he translated the Bible

into Latin. This is the version known as the “Vulgate,” which became

the official Catholic text.

In his geologically informed rendering of the rocky backdrop,

Leonardo has built on a very old landscape tradition. He was likely

measuring himself against, and perhaps in his own mind surpassing,

many of Florence’s grand old masters, such as Giotto and Masaccio,

who often painted massive stone formations in the backgrounds of

their pictures – theatrical sounding-boards for their narratives. He saw

those Florentine artists as commanding figures in the history of paint-

ing, who had advanced the discipline through their direct recourse to

nature. He also considered the periods immediately succeeding them

to be marked by decline, as subsequent painters, he believed, foolishly

looked only to other art rather than to nature. Leonardo’s historical

outline implies that he, a country boy like Giotto, was the leader of the

third great wave of art’s resurgence through commitment to nature.

In this way, he turned his provincial background into a virtue and

advantage. He wrote:

After these [artists] came Giotto the Florentine, and he –

reared in mountain solitudes, inhabited only by goats and