Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

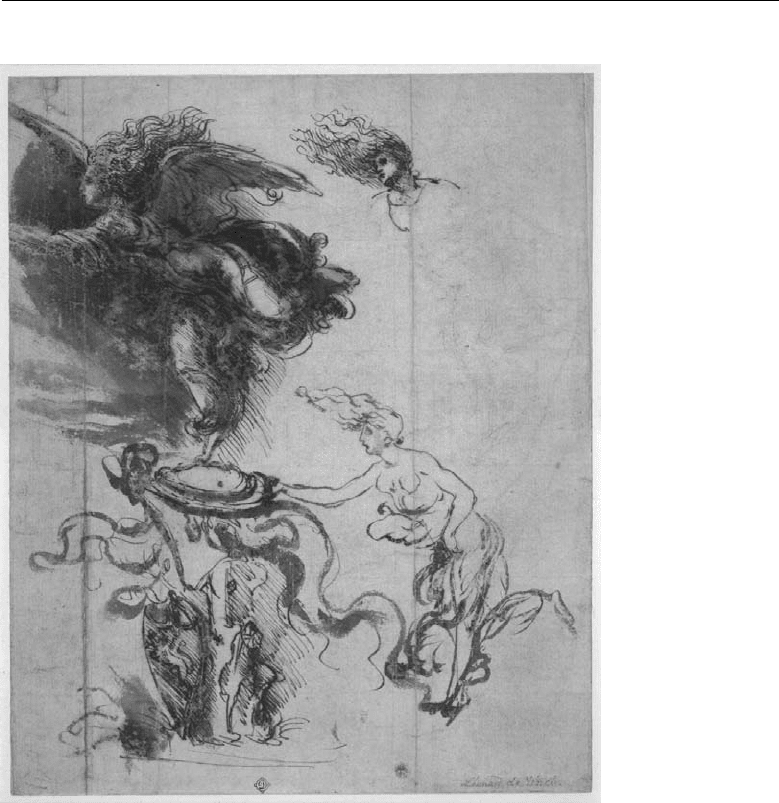

22. Leonardo and Allegorical Conceits for the Medici Court 147

Figure 63.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies of Figures of

Fortune and Fame, Shields

around a Flaming Tree

Stump,c.1481,penand

ink with wash, London,

British Museum (1895-

9-15-482).

C

The

Trustees of the British

Museum/Art Resource,

NY.

of a highly intellectual and philosophical nature, such as the Primavera,

layered with classical allusions and oblique marital references that the

Neoplatonists of the court had provided. The general perception in

Florence may have been that Botticelli was the best painter for erudite,

classical subjects and Leonardo for scenes and details of natural beauty.

As we previously noted, Verrocchio and his shop hardly ever tackled

or developed much of a reputation for rendering antique subjects.

Writing around 1488, one proud citizen of Florence, Ugolino Verino,

compares Botticelli to the ancient Greek painter Apelles, known for

his complex allegories, and Leonardo to the antique master Zeuxis,

remembered for painting on a wall a bunch of grapes so lifelike that

birds pecked at them. If this was the common view of the two artists,

then Leonardo must have been further demoralized when he saw the

148 The Young Leonardo

finished Primavera, in which Botticelli showcased his skills in landscape

and still-life, painting no fewer than thirty distinct species of plants

and flowers.

Botticelli’s influence again proved inescapable when, around the

same time, Leonardo struggled to devise another allegory, perhaps

related to his Fortune and Death sheet. On a drawing in the British

Museum (fig. 63), marked by fits and starts, he developed a scenario

featuring Fame and Fortune. As always, his “thinking on paper” spilled

from right to left and from bottom to top. He began at lower right

with the figure of Fortune, precariously balanced on toe-point, an

unpredictable, shifting wind blowing her long hair forward and the

gown from her chest. With what appears to be a round buckler,

she extinguishes a fire that blazed through a pile of shields, war tro-

phies assembled around a tree stump. Inspecting what he had drawn,

Leonardo must have realized that the viewer would not easily grasp the

meaning of the flaming shields – they probably stood for military fame

– and that the conceit of the dropped dress was less than inspiring.

Commencing again at top right, he quickly sketched Fortune in

stylus and then started to retrace his lines in pen and ink. He advanced

only as far as the head and shoulders when he suddenly had a minor

inspiration (or misgiving) and decided to represent a personification

of Fame, at left. Fame, he wisely concluded, albeit unoriginal, would

be a more elegant surrogate for a smoking mound of battle souvenirs.

Once committed to the figure of Fame, he let his pen and brush fly

with abandon, realizing her in a painterly flourish of ink washes. In

the process, Leonardo cannibalized the toe-point pose of (the lower)

Fortune. Thus, if he wished to avoid monotony, he would have needed

to find a different way to complete the figure he had begun at upper

right. For whatever reason, he did not address the issue, and his ideas

seem to have progressed no further. Unfortunately, he appears never

to have translated into paint his glorious figure of Fame, which recalls

certain Verrocchio angels and, more strongly, in pose and propulsion,

those of Botticelli – a grudging tribute on Leonardo’s part. In their

sweeping movements, the Fame and Fortune of the drawing also

recollect the mingling women who enliven the background of his

Adoration of the Magi.

If Leonardo’s first allegory of Fortune referred to Lorenzo, then

one logically may wonder whether the British Museum drawing was

intended to honor his brother, Giuliano, because the only measure of

22. Leonardo and Allegorical Conceits for the Medici Court 149

fame the young man had achieved, before Fortune snuffed out his life,

was based on his military prowess or, better to say, “aptitude.” His coat-

of-arms (impresa)wasabroncone, a tree stump, with flames shooting

out from where the branches had been cut off. Vasari describes it,

in one place, as a troncon tagliato, or severed trunk. Discernable on

Leonardo’s crested, trophy shields are a rampant-lion device and what

might be a fleur-de-lys. Neither motif was specifically associated with

Giuliano, but both were symbols of Florence – the lion a variation

on the marzocco, the heraldic, leonine emblem of the city. Although

Leonardo would later invent his own, imaginative allegorical language,

at this point in his career, he was in no position to improvise extensively

on established Medici imagery.

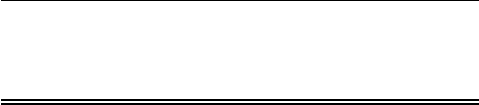

23. Early Ideas for the Last Supper

W

hile conceiving the ill-fated ADORATION OF THE MAGI,

Leonardo, who always played out myriad variations on

an idea or theme, also created numerous, vibrant drawings for an

Adoration of the Shepherds, Nativity,andVirgin of Humility (a northern

European convention in which Mary and the Infant Christ are shown

seated on the ground) – that is, the whole range of traditional, artistic

subjects that dealt with the first days after the Incarnation (fig. 64).

The fluidity of his mind was such that the subjects probably evolved

with the movement of his pen. This free flow of thought extended

as well to the disposition of Saint Joseph, who in some studies has

lost the sweet-natured puzzlement one usually sees in Renaissance

portrayals, appearing, instead, severe and admonitory. In contrast, on

other sheets, Leonardo joyfully imagined the attendant angels as the

most nimble and daring of aerial acts and the Christ Child and Saint

John as almost acrobatically inclined.

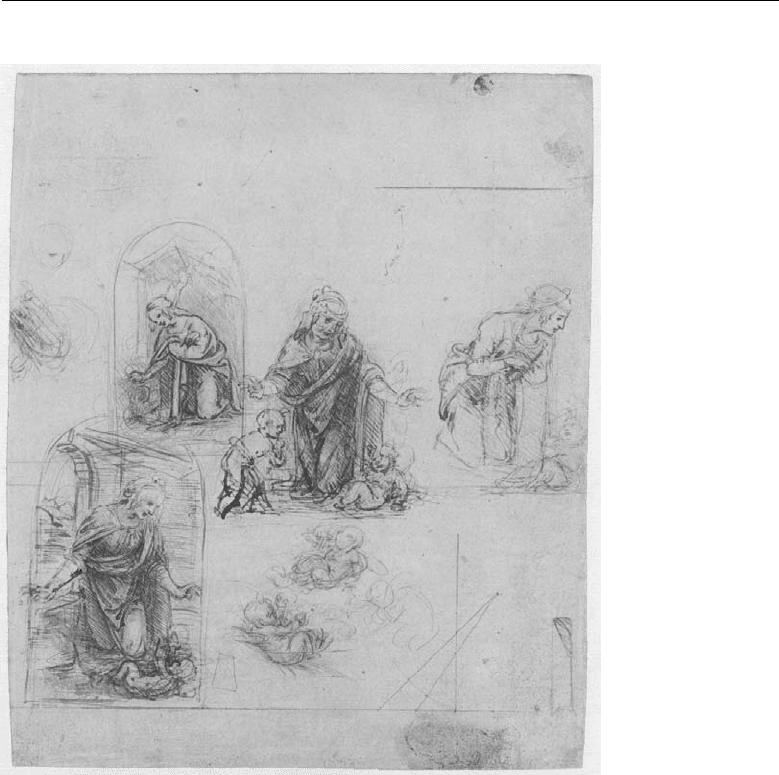

Very comparable squirming babies, no doubt rendered at approx-

imately the same time, appear in a remarkable series of studies by

Leonardo representing the Virgin and Christ Child with St. John the

Baptist, on a sheet now preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,

New York (fig. 65). Touchingly, he has carefully observed and recorded

the movements of an infant who wishes to get off his back – struggling

mightily with hands and feet flailing, or else reaching up to his mother

in the hope that she will lift him. Although Leonardo appears never to

have translated into paint any of these lively figural groups, he would

revisit them years later when devising his majestic altarpiece known as

the Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre) and a long-lost picture of the mythical

Leda and the Swan, a mortal woman with the lascivious god Jupiter, in

avian disguise, surrounded by their newly hatched brood.

151

152 The Young Leonardo

Figure 64.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Study for an Adoration of

the Christ Child,c.1481,

pen and ink, Venice,

Gallerie dell’ Accademia

(256). Cameraphoto

Arte, Venice/Art

Resource, NY.

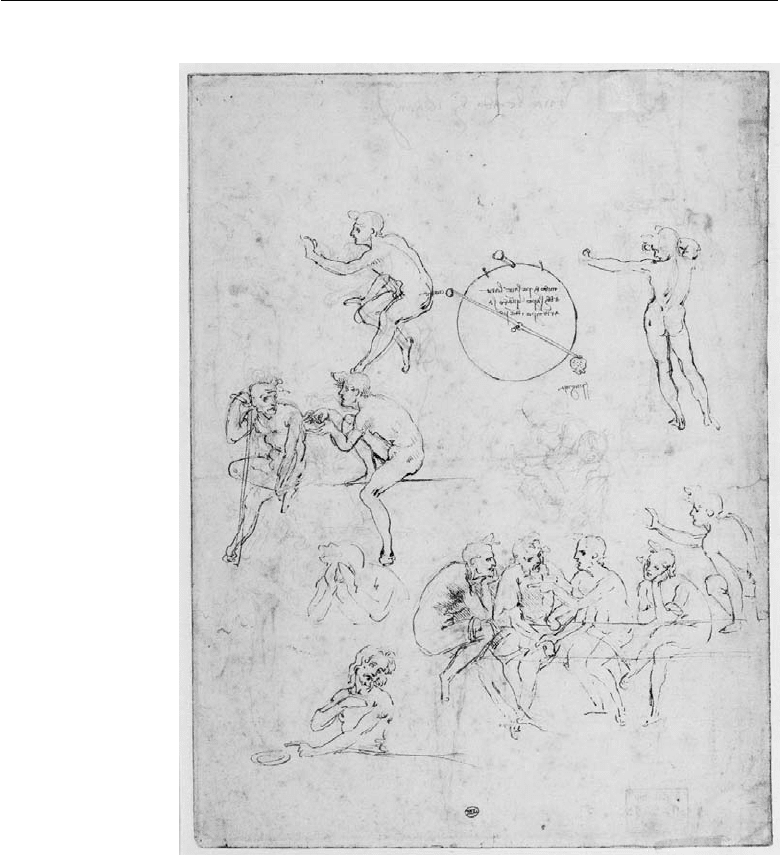

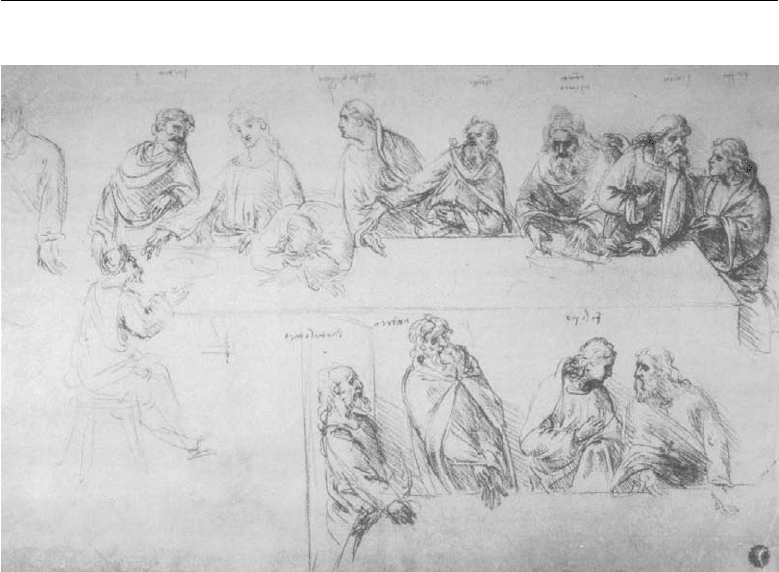

The seeds of another major painting were also sown among

Leonardo’s studies for the Adoration of the Magi – two spirited, pen-

and-ink sketches (c. 1481)foraLast Supper accompany Adoration draw-

ings on a sheet preserved in the Louvre (fig. 66). Presumably made

without a commission for a painting in hand or in mind, these Last

Supper studies, together with those for the Adoration, can be regarded

almost as a pictorial catalogue of various responses to divine reve-

lation or pronouncement. Imprints of a brief and spontaneous, cre-

ative ferment, the drawings would nevertheless endure in use, serving

Leonardo as stimuli or models for decades. At bottom left, he por-

trays an uncharacteristically agitated Christ, finger pointing and hand

on heart, announcing at the Last Supper that one of the apostles will

betray him. Just above, the apostle John, devastated by the news, buries

his face in his hands. At right, a lively group of discussants sits around a

table, prefiguring the dynamic interaction of the apostles in Leonardo’s

subsequent Last Supper designs and painting.

The artist’s decision to represent this most dramatic moment was

not, contrary to much that has been written, an innovation on his part.

23. Early Ideas for the Last Supper 153

Figure 65.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Designs for an Adoration

of the Christ Child,c.

1481–82,metalpoint

with pen and ink on

pink prepared paper,

New York, Metropoli-

tan Museum of Art

(17.142.1). Image copy-

right

C

Metropolitan

Museum of Art/Art

Resource, NY.

Again, Leonardo followed Florentine precedent, notably the Last Sup-

pers of Andrea del Castagno (1445–50) and Domenico Ghirlandaio

(1480), created for the refectories of Sant’ Apollonio and Ognissanti,

respectively. Indeed, Ghirlandaio’s recently completed picture may

have been the catalyst for Leonardo’s flickering thoughts on the sub-

ject. However, he chose to make the actors’ gestures more emphatic

and obvious than those of Ghirlandaio: as Leonardo would later advise,

“figures must be done in such a way that the spectators are able with

ease to recognize through their attitudes the thoughts of their minds.”

Ultimately, when he painted his famous Last Supper (c. 1495–97)for

the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, he chose not to

show Christ in the act of speaking but in the immediate aftermath,

just as Castagno and Ghirlandaio had done in their frescoes. Further-

more, like his predecessors, Leonardo portrayed Saint John in his early

154 The Young Leonardo

Figure 66.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies of Four Male

Figures, Half-Length

Studies of Christ and St.

John, Studies of Figures in

Conversation at a Table,c.

1481, pen and ink over

leadpoint, Paris, Louvre

(2258). R

´

eunion des

Mus

´

ees Nationaux/Art

Resource, NY.

Louvre drawing and in later, preliminary studies for the mural, as over-

come by emotion and collapsed on the table (but not in the painting

itself, where John swoons to the left). John’s presence in the mural,

never questioned until recently (in popular literature), was required

not only by scripture but also by Leonardo’s need for dramatic, pic-

torial contrast, for the telling foil the wilting saint makes to the figure

of Christ, a calm axis of resolve.

By the time he worked on the Milan painting, Leonardo, through

experience and better-honed powers of observation, had learned a

good deal more about human anatomy, psychology, and physiological

reactions. Now almost invisible in the poorly preserved mural, but

23. Early Ideas for the Last Supper 155

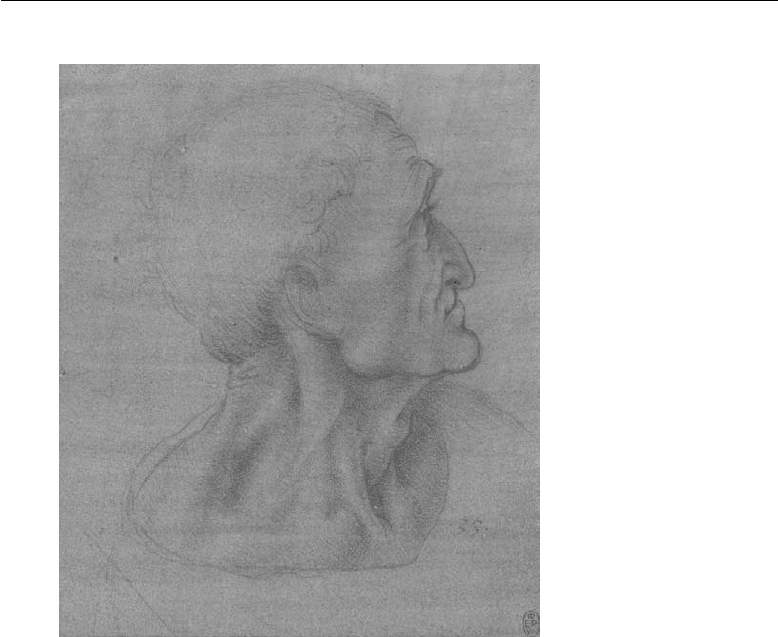

Figure 67.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Head of Judas,

c. 1493–95,red

chalk on red-ochre

prepared paper, Windsor

Castle, Royal Library

(12547). The Royal

Collection

C

2010

Her Majesty Queen

Elizabeth II.

seen clearly in his preparatory drawings (figs. 67 and 68), is the subtle

range of emotions he could capture, including his observations of vol-

untary and involuntary responses: the bulge of an artery in the neck

or vein in the forehead of the traitor Judas, trying unsuccessfully to

conceal his anxiety; the prominent Adam’s apple of James the Greater,

conspicuously rising with his emotion; the faces of vulnerability and

of denial, both conscious and unconscious. In shock, Matthew absent-

mindedly and pathetically busies himself with a fish on a plate; the

hands of some apostles pointlessly clutch their garments or hang in

desperation. Barely legible in the painting (more so in early repro-

ductive prints) is the network of nervously crossed feet beneath the

table.

Leonardo’s perceptive and keen focus on veins and arteries in the

preliminary drawings for the Last Supper is likely owed in part to his

familiarity with the writings of Aristotle, who was one of the first

to advance a psychophysical theory of emotions, connecting them

to cardiovascular manifestations. For the Greek philosopher, unaware

of the functions of the central nervous system, the brain had no

156 The Young Leonardo

Figure 68.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies for the Last

Supper,c.1493–95,red

chalk, Venice, Gallerie

dell’Accademia (254).

Alinari/Art Resource,

NY.

psychological significance; he believed that the heart was the center of

the soul and of feelings, engendered by the warm blood that collected

there. He and his cardio-centric followers thought that blood, literally,

simmered in that organ when a person became angry. This became

a commonly held notion in the Middle Ages and Renaissance; even

the folksy little Fior di virt

`

u quoted Aristotle in reporting that anger

“is a disturbance of the soul caused by a vengeful afflux of blood to

the heart.” According to similar reasoning, when an individual was

afraid or surprised, the warm fluid would “flee” from the brain and

the cooler, upper parts of the body to the heart, where it could induce

palpitations.

Although Leonardo knew of the nervous system and preferred to

locate the soul in the brain, he nevertheless concurred with Aristotle’s

estimation of the heart as the center for the blood and its “vital spirits.”

Thus, in rendering the engorged veins in the heads of the upset

apostles, Leonardo astutely noted the sudden movement of blood –

he simply had its direction incorrect. Such misconceptions would also

undermine the validity of his work when he attempted to “map out”

the vascular system in his anatomical drawings of that period. He

regarded it as an inverted branching tree, with sanguinary flow mainly