Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

17. Leonardo as Portraitist and Master of the Visual Pun 117

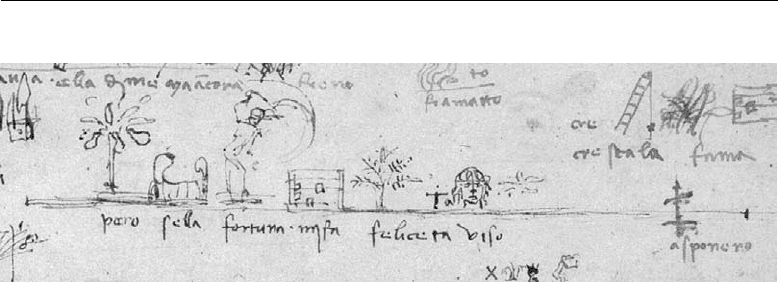

Figure 49.

Detail of “Yarnwinder”

rebus at upper left of

fig. 47. (Reversed for

legibility) The Royal

Collection

C

2010

Her Majesty Queen

Elizabeth II.

would ever devise, as he challenged the sonnet writers and courtiers

in their own arena of clever word games.

Many of Leonardo’s rebuses are short, comprising only two or

three images. A doodle of a sage plant (in Italian, salvia) next to

the word “me” forms the imploring “salvi a me” or “save me!”; the

sketch of a lion (leone) guarding some flames (signifying “burning” or

“arde”) and two tables (deschi) creates the term “lionardeschi,” the name

Leonardo’s followers were called; and a drawing of a holy or pious cat

(pia gatta) with wings engenders the Italian sentence “pia gatta vola”–

“pious cat flies” – or, when said quickly, the phrase “piang’ a tavola,”

which can mean either “cry at the table” or “painted on panel.” Other

of Leonardo’s rebuses were a little more ambitious and clever, such as

the fishhook (amo, in Italian) he drew beside a musical score, with part

of the vocal musical scale “ut re mi fa so la.” In the Middle Ages and

Renaissance, this scale, or solmization, invented by a Tuscan, Guido da

Arezzo, in the eleventh century, comprised only these six notes, and

“ut” took the place of “do.” The artist’s word-image reads: l’amo re

mi fa sol la [za] re,orl’amore mi fa sollazzare – “love gives me pleasure”

or “love amuses me.” The second, more literal, translation would be

in keeping with Leonardo’s playfully cynical attitude, evident in his

aforementioned slur on romance and procreation.

It seems that Leonardo even managed to integrate a rebus into at

least one of his religious pictures. The eponymous prop of his Madonna

of the Yarnwinder (c. 1501; fig. 48) appears to derive from one of the

visual puns on the Windsor sheet. At the upper left of the page is a

series of thumbnail sketches (fig. 49), with accompanying inscriptions,

that represent from right to left: a pear tree (pero), a saddle (sella), a

woman with a sail (fortuna – a personification of fortune), two notes

on a musical stave (mi and fa), a fern (felce), the letters “tal,” a face (viso),

and a black yarnwinder (aspo nero). When recited together, Leonardo’s

118 The Young Leonardo

word-pictures form the whimsical sentence, “Pero se la fortuna mi fa

felice tal viso asponer

`

o!” – “However, if fortune makes me happy, I will

show such a face!” The words “aspo”and“nero” merge to make the

exclamatory word/phrase “asponer

`

o” – “I will show.”

Placed prominently in Leonardo’s painting, the word-image

“asponer

`

o” has a special resonance. In the picture, the Christ Child not

only eagerly seizes the instrument, but, with his left hand, emphatically

points heavenward – a gesture, often associated with John the Bap-

tist, that indicates “I will show” the way to redemption. Further, the

bold motion of the child’s arm, proximate and parallel to the crosslike

yarnwinder, suggests that this salvation will come through his sacri-

fice. The painting was intended for the esteemed French statesman

and diplomat Florimond Robertet, a polyglot who much appreciated

this sort of wordplay and owned other pictures with imbedded visual

puns. One of his personal heraldic devices featured pruned, flowering

branches or fleurs

´

emondes, an allusion to his Christian name. It must

have occurred to Leonardo that such nominal word combinations

were not so different from the clever, bogus etymologies of saints’

names that he had read as a youth in the Golden Legend.

Although Leonardo’s rebus in the Madonna of the Yarnwinder was

perhaps unprecedented, it would not remain unique in sixteenth-

century European painting. The Lombard artist Lorenzo Lotto

inserted in his Portrait of Lucina Brembati (c. 1518–20) the well-known

rebus of a moon (luna) divided by the letters “ci”; and the German

painter Hans Holbein’s French Ambassadors (1533) includes the famous

anamorphically distorted skull, a momento mori, or reminder of death,

whichisalsoprobablyapunontheartist’sname:hohl Bein, or hol-

low bone. By the third quarter of the sixteenth century, rebuses were

common enough in Italian emblems (devices or coats-of-arms with

mottos) that the writer Giovanni Andrea Palazzi, regarding them as

low-minded and, possibly, as a French import, felt the need to dispar-

age them in his Discorsi sopra l’imprese (Discourses on Devices).

Any francophobia aside, Palazzi was probably right in assign-

ing a French origin to the heraldic phenomenon. Visual puns and

rebuses had been popular features in the imprese or devises of France

for centuries. Since at least the time of King Louis Le Jeune, who,

in the twelfth century, ordered for his son, Philip Augustus, a blue

dalmatic sewn with gold fleurs-de-lys, a flower whose name – as

Fleur de Loy – played on his own, visual puns were ubiquitous in

17. Leonardo as Portraitist and Master of the Visual Pun 119

French heraldry. Throughout the Middle Ages and early Renaissance,

similar puns appeared on countless French chivalric shields, called

armes parlantes for their phonetic character, including those of Enguer-

rand de Cand

´

av

`

ene, a count of St. Pol in the late twelfth century,

whose escutcheon bore a sheaf of oats (canne d’avoine), and Gui de

Munois, a thirteenth-century monk of St. Germain d’Auxerre, whose

clever seal featured a cowled ape in the sky, rubbing its back with both

hands – a rebus that could be recited as “singe-air-main-dos-serre” (mon-

key [in the] air [with his] hand squeezes [his] back). Two centuries

later, the Renaissance chronicler Jean Juvenal des Ursins reported

that, in 1416, the dauphin Louis emblazoned his standard with a rebus

comprising a golden letter “K,” a swan (le cygne), and a golden “L”

to proclaim his romantic interest in a certain young woman of the

Casinelle family, one of his mother’s ladies in waiting.

Leonardo’s verbal punning and compilation of rebuses were thus

not merely idle amusement but had practical application – and, for

him, career-enhancing potential. He would find the French courtly

pretensions of the Medici chivalric jousts and Florentine literati in

the northern Italian city of Milan as well. There the tyrant Ludovico

Sforza, with a consummate narcissism worthy of royalty, commis-

sioned dizzyingly complex, literary conceits and pictorial allegories

that honored him and his rule. Called Il Moro, or “The Moor,” after

“Maurus,” his baptismal second name and dark complexion, Sforza

elicited from Leonardo the sycophantic, only semiclever sentence: “O

moro, io moro se con tua moralit

`

a non mi amori tanto il vivere m’

´

e amoro”(“O

Moro, I shall die if with your goodness you will not love me, so bitter

will my existence be”) – a literary display that employs five punning

variations on “moro” in sixteen words. The artist also contrived visual

puns for Sforza, featuring a mulberry tree (morus in Latin). Of course,

such talents would have been no less appreciated when Leonardo, at

the end of his life, secured employment in Robertet’s milieu, at the

French court of King Francis I.

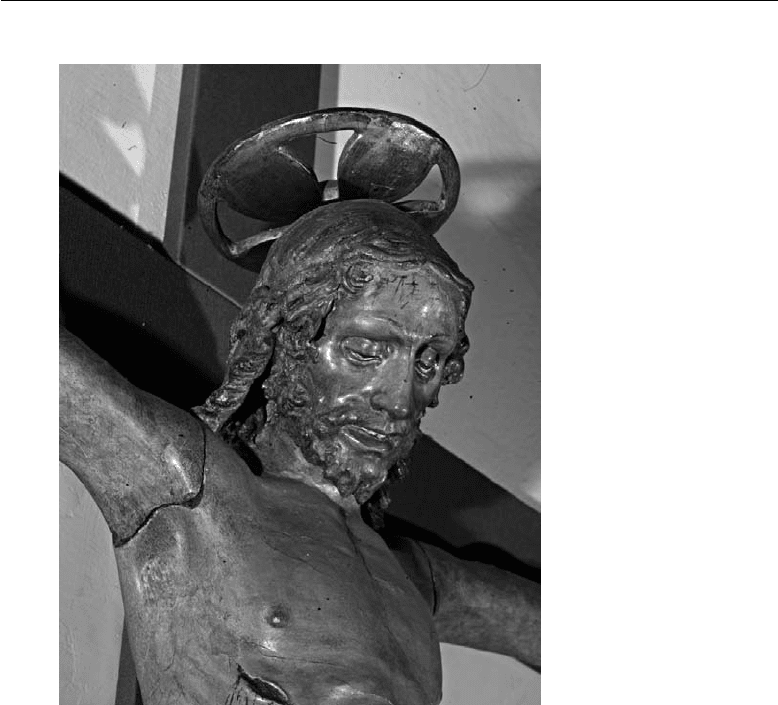

18. The Young Sculptor

I

n the period just before or after leona rdo finished his

portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci, that is, the late 1470s or early

1480s, he may have turned his attention, for a brief time, to sculpture.

A growing consensus of scholars believes that he was probably respon-

sible for the pensive, terracotta Bust of the Young Christ in an Italian

private collection (fig. 50). Although the attribution to Leonardo must

remain tentative, because no other sculpture by him survives for com-

parison and the piece is completely undocumented, certain aspects of

the work point to his hand. The facial type and handling of the hair

suggest that the sculpture comes from someone trained in the Verroc-

chio shop; comparisons can be made to Verrocchio’s terracotta bust

of Christ in a private collection in London and to the physiognomies

of the master’s David (Bargello Museum), Christ and Saint Thomas,

and, especially, in the pronounced asymmetry of the eyes and queerly

bulging eyelids, his Christ of the Crucifixion (c. 1470–75; fig. 51), also

in the Bargello.

Yet, typical of Leonardo, the Young Christ has been invigorated

in a novel way – the head is turned, breaking the usual symmetry

of such busts (as Verrocchio would do in his terracotta portrait of

Giuliano de’ Medici of c. 1478), and Christ’s expression has been

“humanized,” made momentary and unquiet. With eyebrows raised

and eyes lowered, he seems to be intellectually assimilating something

he has just observed or mulling over a response to something that he

has just heard, as if caught up short in his discussion with the elders in

the temple, recounted in the Gospel of Luke (2:46–50). In his personal

reflection on Christ, Leonardo, as one might expect, imagines him

to be similarly thoughtful and questioning, as much the reasoning

philosopher, the Old Testament teacher as Savior or healer.

121

122 The Young Leonardo

Figure 50.

Leonardo da Vinci

(attributed to), Bust

of the Young Christ,c.

1478–80?, terracotta,

Rome. Reproduced by

kind permission of the

Heirs of Luigi Gallandt

and Sotheby’s.

The passage in Luke is the only biblical account of Jesus’ matura-

tion, reporting that, in just three days, the twelve-year-old had remark-

ably increased in “wisdom and stature.” In this respect, Leonardo’s

bust would have served as an appropriate coming-of-age present for a

young man who had reached adulthood (like Renaissance paintings of

Hercules at the Crossroads and the Dream of Scipio, which were intended

to invoke an adolescent’s choice between a life of virtue versus vice,

or duty over pleasure). The work may have had a special meaning for

the artist. Around the time of its execution, he was probably about

to separate from the Verrocchio shop and launch his independent

career.

The portrayal of Christ as an adolescent in a freestanding, sculp-

tural bust is also unusual, but it would not be entirely unexpected for

Leonardo, who pondered over religious subjects incessantly, often rein-

terpreting them, and who earlier, unconventionally, portrayed Saint

John the Baptist at that stage of life. It has not been sufficiently noted

that, despite occasional fits of irreverence, Leonardo was extremely

devout – both God-fearing and God-admiring – as his writings,

throughout his life, make abundantly clear:

I obey thee, O Lord, first because of the love that I ought

reasonably to bear thee; secondly, because thou knowest

how to shorten or prolong the lives of men.

18. The Young Sculptor 123

Figure 51.

Andrea del Verrocchio,

Detail of Head of Christ

in Crucifixion,c.1470–

75, bronze, Florence,

Museo Nazionale del

Bargello. Polo Museale.

Fortune is powerless to help one who does not exert him-

self. That man becomes happy who follows Christ.

Falsehood is so utterly vile that, though it might praise the

great works of God, it offends against his Trinity.

The Lord is the Light of all things –.

The Creator does not make anything superfluous or defec-

tive.

Rejoice that the Creator has ordained the intellect to such

excellence of perception.

These thoughts, most of which he wrote only for himself, are at

odds with Vasari’s assertion that Leonardo’s “heretical frame of mind –

caused him not to adhere to any kind of religion, considering that it

124 The Young Leonardo

was perhaps better to be a philosopher than a Christian.” The only

“heresy” of which we know is the artist’s deep skepticism with regard

to the biblical Deluge, because of his knowledge of the behavior of

natural bodies of water; “how,” he asked, “did the waters of so great

a Flood depart if it is proved they had no power of motion?”

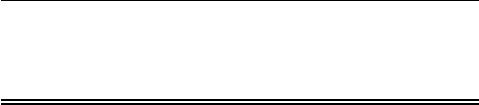

19. The Madonna Litta

F

rom leon a rdo’s p a ssing mention abo ut beginning “the tw o

Virgin Marys” and his copious drawings that often include

sketches for several projects on one sheet, one can fairly presume that

he liked to work on several things at once. This may have been partly

owed to his obsessive nature and been partly a habit he picked up from

Verocchio, who, we know, enjoyed moving back and forth between

concurrent projects. Along with the Benois Madonna, Virgin and Child

with the Cat, Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci,and,possibly,theBust of

Christ, Leonardo probably devoted some time in the very late 1470s,

and more focused attention in the early 1480s, to the conception of a

nursing Madonna in profile, known from a quick sketch on a sheet at

Windsor (c. 1478–79), which shows Mary both full-face and in three-

quarter view (fig. 3); an exquisite, metalpoint study for the Virgin’s

head (c. 1481; fig. 52); and a workshop picture, often attributed to his

follower Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (fig. 53).

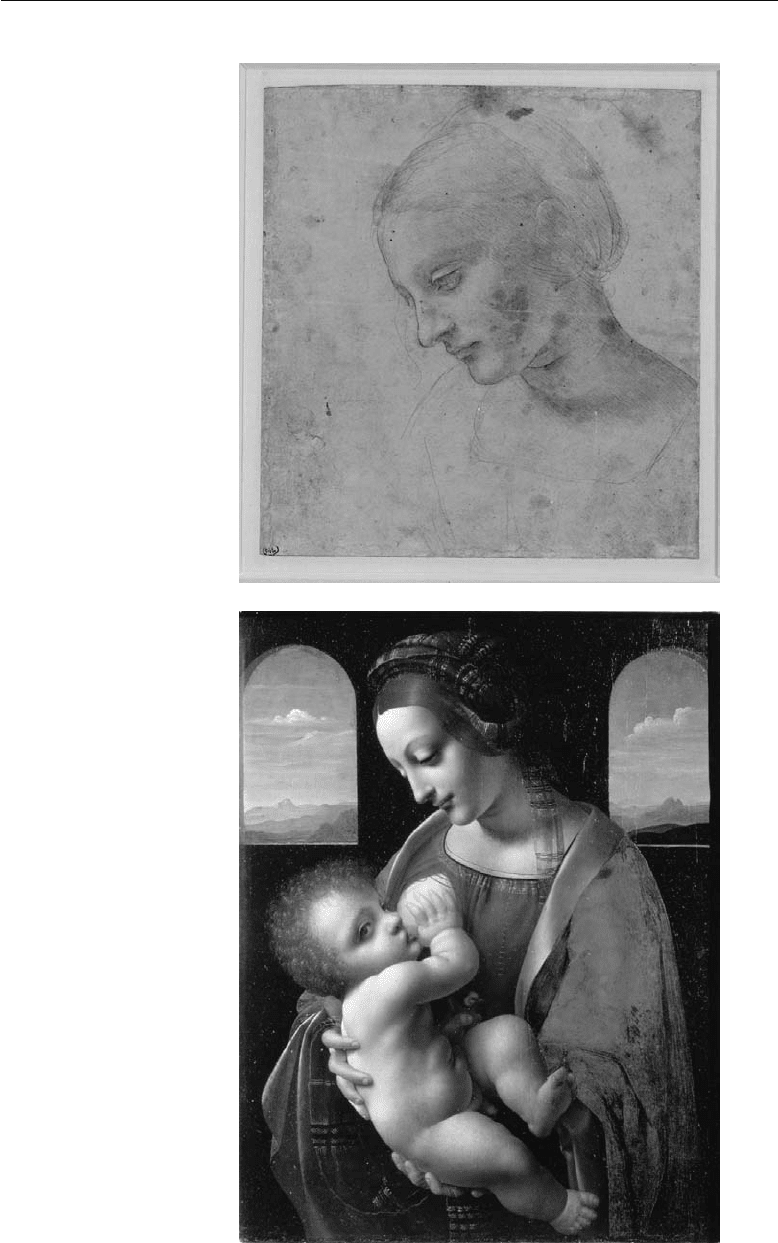

The painting, referred to as the Madonna Litta (after the Milanese

collector, Count Antonio Litta, from whom it passed to the State Her-

mitage Museum, St. Petersburg), may have been started by Leonardo

in 1481 and then put aside when he became too involved with the

important commission for anAdoration of the Magi from the monks of S.

Donato a Scopeto. Boltraffio or another shop assistant painted most of

the work, all that is now visible, probably soon after Leonardo arrived

in Milan in 1482. He mentions in the brief “inventory” he made in

that year a “Madonna finished” (probably the Benois Madonna)and

“another, almost finished (maybe an exaggeration or self-deception),

whichisinprofile,”likelytheMadonna Litta. Leonardo habitually

carried paintings, often incomplete, on his travels. In some cases, he

probably hoped to find spare time to finish them. In other cases, such

125

126 The Young Leonardo

Figure 52.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Study for the Head of

the Virgin,c.1481,

metalpoint heightened

with white on pale blue

prepared paper, Paris,

Louvre (2376). Erich

Lessing/Art Resource,

NY.

Figure 53.

Giovanni Antonio

Boltraffio (with

Leonardo da Vinci),

Nursing Virgin with

Goldfinch (Madonna

Litta), c. 1481–84,oil

on panel, St. Peters-

burg, State Hermitage

Museum. Scala/Art

Resource, NY.