Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

13. The Benois Madonna and Continued Meditations on the Theme of Sight 87

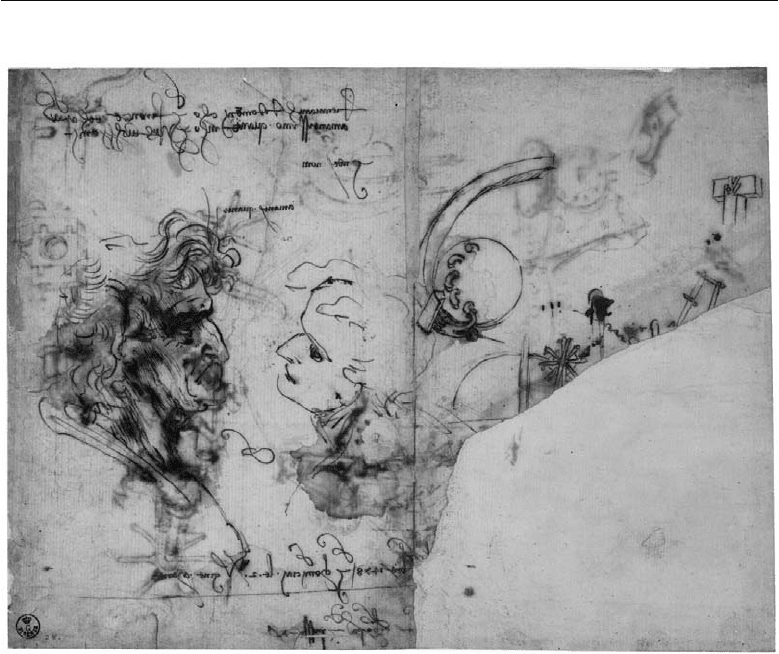

Figure 31.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies of Machines (verso

of fig. 32), 1478,pen

and ink, Florence, Uffizi

(446E). Polo Museale.

Renaissance art. Unconventionally, she seems to be speaking or laugh-

ing, playfully engaged with her child, her radiant vitality accentuated

through Leonardo’s deliberate complications of posture and drap-

ery. Able to observe on a regular basis the interactions between his

half-siblings Antonio and Giuliomo (born in 1479) and stepmother,

Leonardo made a number of sketches that capture the awkward and

unpredictable actions of an infant: wrestling with a cat, snatching a

piece of fruit from a bowl, poking his fingers into his mother’s face.

Drawings executed for the Benois Madonna and for a related work,

depicting the Virgin and Child with a Cat (figs. 38 and 39), indicate

the artist’s desire to make the compositions as dynamic and intri-

cate as possible – a major advance from the more staid, frontal stance

of the Munich Madonna, which, as we have seen, was based on a

Verrocchio prototype. Leonardo had attempted, tactfully and mini-

mally, to distinguish his Virgin and Child with the Carnation from the

standard Verrocchio shop piece by including beautiful, if improbable,

flourishes – the impossibly complex silhouette of the Virgin’s veil, the

watery and convoluted cascades of her dress and shawl. In the Benois

88 The Young Leonardo

Figure 32.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies of Heads and

Machines, 1478,penand

ink, Florence, Uffizi

(446E). Polo Museale.

Madonna, this sort of virtuoso demonstration of twisting form in space

is more credibly and profoundly integrated, with a helix serving as the

core and organizing armature of the entire composition.

One may fairly associate this interest in structures unfolding in

space with Leonardo’s concurrent fascination with gyrating machin-

ery and the use of sprockets, gears, and conveyor belts to transfer

motion from one plane to another. On both sides of a fragmentary

sheet of sketches, dated to 1478 and now in the Uffizi, are various

mechanisms in which Leonardo explored how forces and tensions

could be conducted and controlled in three dimensions (figs. 31 and

32). He conceived the Benois Madonna, with its curving, stepped pro-

jections of arms and legs, its stacked arrangement of revolving forces

and counterforces, as a similarly contained system – a small engine or

clockwork universe of energies in equilibrium.

14. The Madonna of the Cat

S

ketched beside some of the machines on the r agged but

important Uffizi sheet of 1478 is another kind of counterbal-

ance, a contrast between two typologies that would become a fixation

for Leonardo: the wizened, contemplative face of an old man and

the fresh, inquisitive visage of a youth – an embodiment of Aristotle’s

decree that “each thing may be better known through its opposite”

(fig. 32). Eventually, as we shall see, this juxtaposition would carry

religious and spiritual connotations in certain of Leonardo’s works,

notably his representations of the Adoration of the Magi and Last

Supper. However, we might rather assume that, at this relatively early

stage of his career, his musings had something to do with his fam-

ily situation. The grandfather, Antonio, would have been a constant,

possibly doting, presence in the young Leonardo’s life until the old

man passed away in 1464 at age 92. With a father who was mainly

absent, engaged in business in Florence, an estranged mother (who

had moved with her husband to another village), and a stepmother

who died prematurely, Leonardo likely felt a special closeness to his

grandparents, with whom he lived for nearly a dozen years. In the

countless drawings of the aged that he made over the course of his

career, one often senses a certain reverence and intimacy.

Aside from any personal meaning they may have had, Leonardo’s

ubiquitous pairs of contrasting heads, as noted earlier, also reflect his

belief, based on Aristotelian principle, of the elucidating power of

opposition – through which, in some cases, a better understanding of

each of the antipodes may be gained and, in others, a “just mean”

or balance achieved. The skeptical artist continually sought to present

or expose contradictions, and he loved irony. Ultimately, though, as

a Christian philosopher who believed in the profound interrelation

89

90 The Young Leonardo

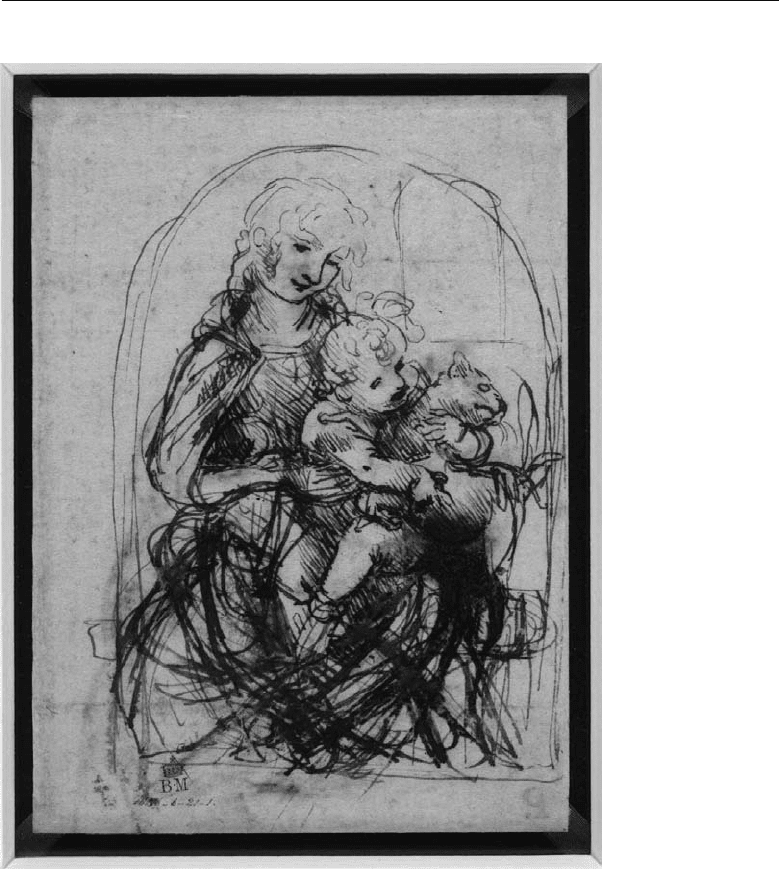

Figure 33.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Sketches of a Child

Holding and Playing

with a Cat,c.1478–

80,penandink,

London, British

Museum (1857-1-10-1).

C

The Trustees of the

British Museum/Art

Resource, NY.

of phenomena in a divinely designed world, he desired a Renaissance

version of the modern, unified-field concept, a reconciliation of all

contrasting ideas and forces.

Near the pair of heads on the Uffizi sheet, Leonardo left the enig-

matic inscription: “ – 1478, I began the two Virgin Marys.” One of

these was presumably the Benois Madonna, the other, perhaps, a Virgin

and Child with Cat, for which, as previously mentioned, numerous

preparatory studies survive, some closely related in composition to the

former work (figs. 33, 35–40). This series of stream of consciousness

drawings is instructive for what it reveals of Leonardo’s rather manic

14. The Madonna of the Cat 91

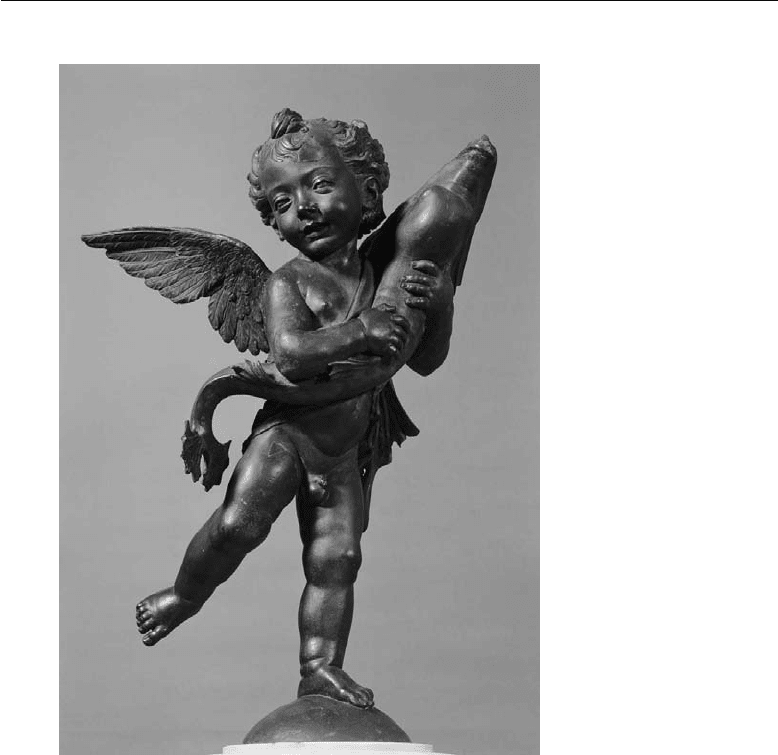

Figure 34.

Andrea del Verrocchio,

Boy with Dolphin,late

1470s, bronze, for the

Medici villa at Carreggi,

now Florence, Palazzo

Vecchio. Scala/Art

Resource, NY.

and circuitous, creative process. He took full advantage of the quick,

weightless movement of the quill pen, which, as many a draftsman

has noted, can seem almost to move of its own accord. Among the

first of these studies may have been the frantic, exuberant sketches

on both sides of a sheet preserved in the British Museum (fig. 33),

where Leonardo captures, in blurred, stop-action frames, a young

child’s good-natured abuse of a cat. He had an uncanny ability to

illustrate swift and minute movements, such as nuances of feline reflex

and exceedingly intricate and fleeting currents in water (the latter

confirmed by modern high-speed photography). Either his eyesight

was extraordinarily quick – and quasi-microscopic in power – or, after

countless hours spent studying animals and bodies of water, he was

just extremely good at speculating about those rapid movements and

patterns in nature that are difficult to observe. Whichever the case, his

loose, fluid penmanship owed much to the example of Verrocchio,

92 The Young Leonardo

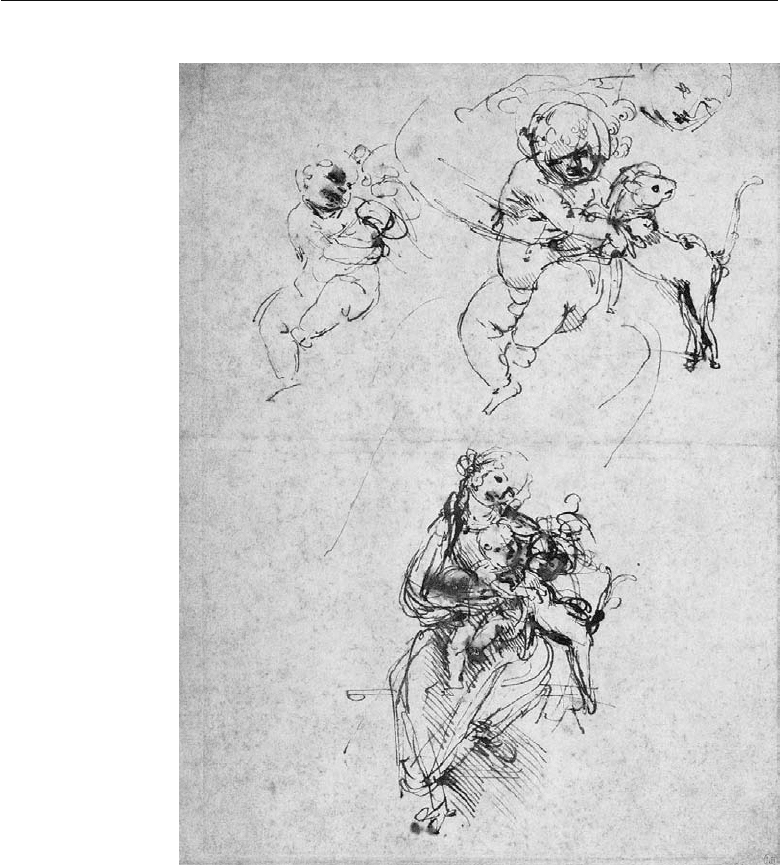

Figure 35.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Study for a Virgin and

Child with a Cat,c.

1478–80,penandink

with wash, Florence,

Uffizi (421E). Art

Resource, NY.

whose manner of sketching was unprecedented in its spontaneity and

vitality.

In these vigorous child-and-cat drawings, the artist was also likely

responding to Verrocchio’s recently completed bronze, Boy with a

Dolphin (late 1470s; fig. 34), which Il Magnifico had just obtained

for his villa at Carreggi, the seat of the Platonic academy of philoso-

phers and so a prestigious and prominent venue. Verrocchio’s giddy,

wriggling statue, with its ambitious spiraling effect, would have posed

something of a challenge to Leonardo. The sketch at bottom left of

the British Museum sheet (fig. 33)appearstobeafirst,directreaction

14. The Madonna of the Cat 93

Figure 36.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies for a Virgin

and Child with a Cat,

c. 1478–80,penand

ink, London, British

Museum (1860-6-16-

98). Polo Museale.

to the sculpture; Leonardo has the child grasp the animal in much

the same manner, and some rough lines suggest that he even consid-

ered extending the boy’s proper right leg, like that of the Verrocchio

bambino. Often regarded as a solitary genius who received ideas from

on high, Leonardo, in reality and in almost every instance, responded

in his art to the recent work of others, particularly to those objects

that were novel in some way. In large part, his brilliance consisted in

his ability to make instant and optimal use of the contributions of oth-

ers – the isolated individual, who feels compelled to invent everything

completely de novo, cannot himself become an innovator.

So goaded, Leonardo continued to explore the subject of a boy

with a cat, usually lashed together in a hopeless tangle and including

a woman (the Virgin) as well, in at least five other sheets. At an early

point in the design process, he considered placing the child, clutching

the cat, on a cushion or platform beside the Virgin (figs. 35 and 36).

94 The Young Leonardo

Figure 37.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies for a Virgin

and Child with a Cat,

c. 1478–80,pen

and ink, Bayonne,

Mus

´

ee Bonnat (152).

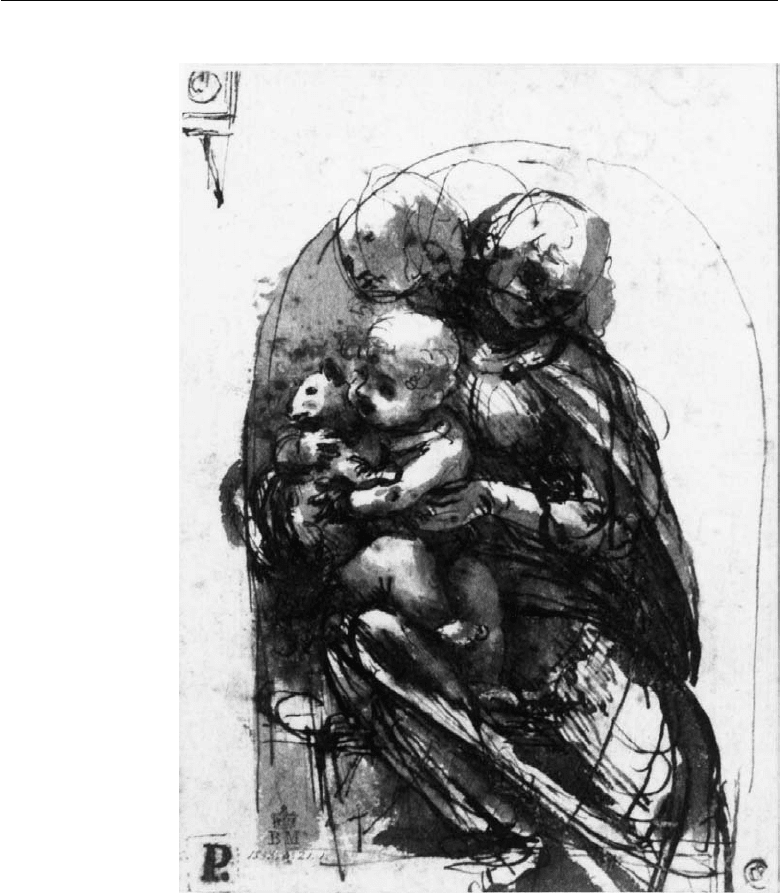

Later, the composition evolved, momentarily, to one very similar to

that of the Benois Madonna, with the three figures in a taut knot

(figs. 37 and 38). He subsequently changed his mind again, tracing the

design right through the sheet with a sharp stylus, reversing and then

altering the poses in pen and wash (figs. 38 and 39). The study closest

to the (planned) painting may be the smallest surviving sketch – the

tender, tiny design now in a private collection, in which the heads of

the three figures seem gently to touch (fig. 40).

Although Leonardo would have found a squirming cat a more

challenging prop than a dolphin, it is difficult to say exactly why he

chose to place that particular animal in the baby’s arms. Of course, as

14. The Madonna of the Cat 95

Figure 38.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Study for a Virgin and

Child with a Cat,c.

1478–80,penand

ink, London, British

Museum (1856-6-21-1).

C

The Trustees of the

British Museum/Art

Resource, NY.

a common household member (perhaps in Ser Piero’s abode), the cat

conveyed domesticity, as did, despite its foreboding symbolism, the

goldfinch, a favorite pet of children in the Renaissance. One should

recall that these small and intimate Madonnas were intended for the

home, usually a bedroom.

It is also possible that Leonardo’s choice of animal-actor was

intended to perpetuate a charming, popular legend that a cat gave birth

to a litter of kittens at the moment of Christ’s Nativity. Other than

that, the cat has no Judeo-Christian significance (curiously, although

worshipped in Egypt for millennia, cats are never mentioned in the

canonical books of the Bible). In ancient Greek mythological texts,

96 The Young Leonardo

Figure 39.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Study for a Virgin and

Child with a Cat (verso

of fig.38), c. 1478–80,

pen and ink, London,

British Museum (1856-

6-21-1). Alinari/Art

Resource, NY.

however, the feline is said to be a proxy of Hecate, goddess of the

dead and the underworld. Perhaps because of this tradition and, cer-

tainly, due to medieval stories of necromancy, the cat was some-

times regarded, like the goldfinch, as an omen of death. In Leonardo’s

Tuscany, there was an old, folk superstition that the sudden appearance

of a cat could portend someone’s passing. A black cat has ominous

associations even today.

Leonardo’s painting of the Virgin and Child with the Cat was either

somehow lost or, in light of the fact that no replicas or variants survive,

was, more likely, never fully realized, the fate of so many of his projects.