Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

11. Leonardo’s Colleagues in the Workshop 77

Figure 26.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Study of a Female Head,

c. 1474–76,penandink

with washes, Florence,

Uffizi (428E). Scala/Art

Resource, NY.

isolated figures, decorative rather than interactive, seem as immobile

as the stone lectern and background trees. Only the distant mountains,

gloriously evocative in their atmospheric shroud, hint at Leonardo’s

inventiveness and ambitions, scientific as well as artistic.

Although still finding his own way artistically, Leonardo was appar-

ently more than happy to nurture his friend Lorenzo di Credi’s creativ-

ity and career – behavior auspicious of the generous and sure guidance

he would one day provide to the young artists who worked for him. In

addition to offering a drawing to Credi for the Baptist of the Pistoia

Madonna di Piazza, he allowed his colleague to peruse his portfo-

lio of studies when Credi needed to design the predella,thelower

register of scenes, for that altarpiece. With good reason, Credi must

have become particularly enamored with Leonardo’s exotically elegant

Study of a Female Head (now Uffizi – fig. 26). The jeweled brooch and

wing motif of the headband indicate that Leonardo conceived her

78 The Young Leonardo

either as an angel or as some sort of allegorical or mythological being.

Credi, however, decided that the bowed head and demurely downcast

eyes would very well suit the Annunciate Virgin in his predella panel,

now in the Louvre. The transformation was made with only minor

adjustments to the headgear and coiffure. Unashamedly, Credi also

appropriated the profile pose of the angel and organization of his pic-

ture from Leonardo’s recently finished Annunciation. Later, according

to Vasari, Credi replicated a Leonardo Madonna and sent his copy to

the king of Spain.

12. Leonardo’s Madonna of the

Carnation and the Exploration

of Optics

P

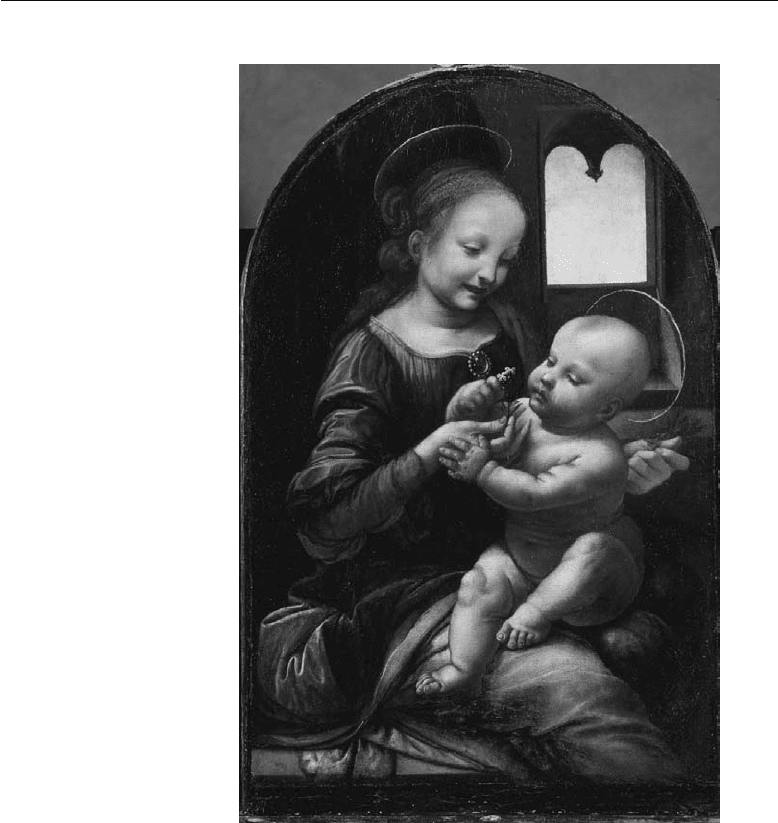

ossibly executed not long after his ANNUNCIATION,and

featuring some of the same faux-alpine topography,

Leonardo’s delightfully curious Virgin and Child with a Carnation of

c. 1476–78 (fig. 27), now in Munich, reveals his inclination to move

beyond studio conventions and to probe with a keener eye the work-

ings of human anatomy and the properties of light. In the panoramic

landscape, glimpsed through windows, Leonardo shows that he could

achieve the atmospheric-perspective effects of the finest Flemish paint-

ings, for which Lorenzo the Magnificent had a special enthusiasm;

precious masterpieces by Jan van Eyck, Petrus Christus, and other

Northern masters graced his palace. With a general concern for Medici

approval, Leonardo no doubt derived some of his imaginative land-

scape elements, as well as the background window motif, from such

pictures. His rugged landscape would have had an inviting familiarity

for a northern European viewer. To Leonardo’s audience, however,

the mountain ranges must have seemed a forbidding wilderness and, in

the context of his painting, suggestive of a primordial, ancient world

now in recession, with the advent of Christ. Also much intrigued by

Flemish art around that time, but less interested in natural topography,

Sandro Botticelli chose to introduce a more sanguine, northern Euro-

pean townscape into the background of his Shooting of Saint Sebastian

of 1474, painted for the Florentine church of S. Maria Maggiore.

The generally presumed date of the Munich picture coin-

cides with the infancy of Leonardo’s half-brother, the long-awaited

Antonio (born 1476), who may have served as a model. For the unusu-

ally young Christ, Leonardo obviously had studied a baby firsthand,

recording but not fully understanding the visual problems experienced

in the first months of life. In the Munich picture, the Christ Child, eyes

79

80 The Young Leonardo

straying and unfocused, reaches almost blindly for the Virgin’s carna-

tion. Ungraceful though this gesture may be, Leonardo renders it with

a fascinated precision, as he does the baby’s doughy flesh. Although

hindered by his ungainly body and underdeveloped vision, the holy

child instinctively wishes to seize the flower, a traditional symbol of

the Passion, specifically the Crucifixion, because of its nail-like buds.

In portraying the truth of what he observed, Leonardo characteristi-

cally reveled in its complexity. A simple exchange between a mother

and child has become, in his hands, a subtle matrix of physiological

mechanics and religious meaning.

Vision and optical effects can almost be considered subtexts of the

Munich picture. In it, Leonardo demonstrates not only his ability to

reproduce bright, outdoor light and soft, ambient interior illumination

but also shows, in the Flemish-inspired, crystalline vase, the small, glass

balls attached to the cushion, and the Virgin’s conspicuous, emerald

brooch that he can imitate the appearance of rays of light which are

refracted, filtered, and reflected. Since the Middle Ages, the emerald

had been viewed as a badge of purity, as the stone was said to splinter

when a virgin was violated. But placed so near to the baby’s eyes,

in the center of Leonardo’s composition, the prominent green stone

probably had additional significance.

From ancient times through the Renaissance, emeralds were

believed to aid eyesight. Aristotle’s successor, the fourth-century b.c.

philosopher Theophrastus, confidently asserted that emeralds were

good for the eyes, pointing out that some people carried emerald

seals with them for intermittent, salutary viewing. Pliny’s first-century

Natural History, the basic encyclopedia of animals, vegetables, and min-

erals in the Renaissance, reported that strained eyes could be restored

to their “normal state by looking at a ‘smaragdus’ (emerald).” Ficino,

at the Medici court, declared that not just emeralds but all smooth,

green materials held therapeutic value for the eyes. This belief persisted

well into the seventeenth century. In his poem “A Lover’s Complaint”

(1609), Shakespeare noted: “the deepe greene Emrald in whose fresh

regard, weak sights their sickly radiance do amend.” Precious and

semiprecious stones and jewels were a frequent topic of conversa-

tion in Lorenzo the Magnificent’s circle, for he owned a significant

number of gems, cameos, and various objects, such as vases and tazze

(cups), carved from carnelians, chalcedony, jasper, and sardonyx-agate.

Leonardo’s later manuscripts indicate that, like Lorenzo, he came to

12. Leonardo’s Madonna of the Carnation and the Exploration of Optics 81

Figure 27.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Virgin and Child with a

Carnation,c.1476–78,

oil on panel, Munich,

Alte Pinakothek.

Bildarchiv Preussis-

cher Kulturbesitz/Art

Resource, NY.

possess Pliny’s opus and specialized books or treatises on precious

stones (lapidari), perhaps by Theophrastus and the German theologian

Albertus Magnus.

In Leonardo’s time, interest in precious and semiprecious stones was

far more pervasive and topical than it is today. This had partly to do

with the fact that, as with the emerald, many precious stones and metals

were valued almost as much for their supposed medicinal (or magically

curative) properties as for their aesthetic qualities. The diamond was

thought to be an antidote for poison and to protect against plague,

the ruby a remedy for flatulence, and the sapphire effective against eye

82 The Young Leonardo

disease. The sparkling, violet amethyst was considered to be a cure for

drunkenness and purportedly made the wearer more nimble-minded

and shrewd in business matters. Ficino and members of the Medici

court and family, notably Francesco I in the later sixteenth century,

consumed significant amounts of powdered lapis lazuli, an expensive

stone used as an artist’s pigment, as well as the “elixir of life,” a form

of potable gold. Properly and regularly ingested, these materials were

believed to counteract excess black bile in the body and consequently

alleviate melancholy.

Despite the original observations and considerable thought that

Leonardo invested in the Virgin and Child with a Carnation,hemade

certain that it would still be recognized as a Verrocchio workshop

product. The Virgin’s features conform closely to the master’s facial

types, widely admired, then as now, for the gentle affection they

exude. Very similar faces and capricious hairstyles are found in several

Verrocchio and Verrocchio-shop drawings, notably two well-known

studies of female heads (one possibly for the lady in the joust-standard

design) in the collections of the British Museum and Louvre. The need

for “branding” aside, Leonardo also emulated his mentor’s idealized

countenances and intricate coiffures because, as Vasari noted, he clearly

much appreciated their inventiveness. It is interesting to note, however,

that when the impressionable and loyal Credi painted his tiny Madonna

of the Pomegranate in these years (c. 1476–78), his primary model was

Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with the Carnation, and only secondarily

did he look to Verrocchio’s works.

13. The Benois Madonna and

Continued Meditations on the

Theme of Sight

M

any of the same themes and inquiries concerning

vision continued to preoccupy Leonardo when he exe-

cuted another, better-known painting of the Virgin and Child not

long afterward, the so-called Benois Madonna (c. 1478–80), named for

its last private owner (Leon Benois), and now in the State Hermitage

Museum in St. Petersburg (fig. 28). In what can be regarded almost as

a further elaboration on the actions of the Munich infant, Leonardo

portrayed the older, and rather immense, child in the Benois Madonna

as gamely trying to focus his eyes on a sprig of cruciform-shaped

flowers. The painter would have had a largely erroneous idea about

the nature of the child’s struggle, because he did not know of the

existence of lenses in the eyes.

Instead, following the eminent Florentine theorist Leon Battista

Alberti, Leonardo, at least into the 1490s, ascribed to the fallacious,

Platonic “theory of emission” in the operations of sight – that is,

the belief that the eyes emit rays that extend to the object seen. In

his widely read treatise On Painting of 1435, Alberti had applied the

geometric elaboration of Euclid’s Optics (c. 300 b.c.) to the visual

rays (opseis) that Plato described in his fourth-century dialogue, the

Timaeus. There, Plato spoke of such fictive rays as an ocular “fire”

mixing in sympathy with external light. With great authority, Alberti

explained how an infinite number of these rays issued from the eyes,

the most powerful being the central one or “centric ray,” which, he

believed, played “the largest part in the determination of sight.”

Exactly contrary to the true nature of vision, which involves intro-

mission, the reception of light from an object into the eyes, Leonardo

nevertheless wrote about and drew diagrams of this imaginary phe-

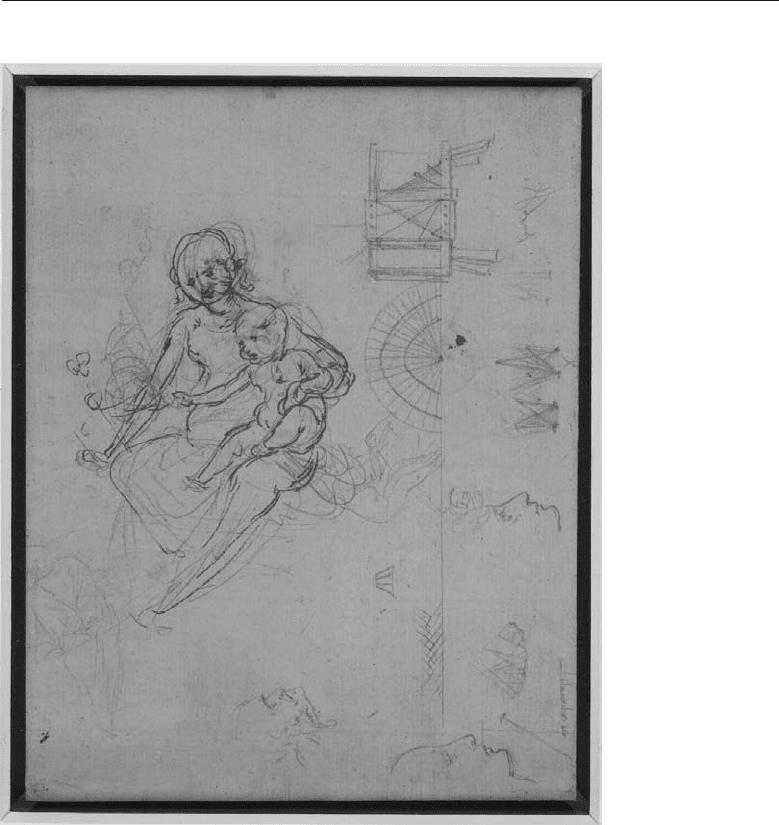

nomenon. In fact, along the margins of one of his preliminary studies

83

84 The Young Leonardo

Figure 28.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Virgin and Child

with Flowers (Benois

Madonna), c. 1478–80,

oil on wood panel,

transferred to canvas,

St. Petersburg, State

Hermitage Museum.

Scala/Art Resource,

NY.

for the Benois Madonna, he made three tiny “technical” sketches that

show, from right to left, parallel centric rays emitted from a pair of eyes

looking forward, intersecting rays from eyes turned slightly inward,

and, last, rays intersecting from eyes turned markedly inward (figs. 29

and 30). The final diagram is in keeping with the eyes of the Christ

Child in the Benois Madonna, who assertively guides the hand of his

mother, so that the flowers will be brought into the crossing of his

ocular rays.

Leonardo would go on to devote much of his life to investigations

of optics, binocular vision, and perception and eventually would come

to an uneasy reconciliation of the theories of emission and intromis-

sion. Thus, although he made some subtle and astute observations,

13. The Benois Madonna and Continued Meditations on the Theme of Sight 85

Figure 29.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Virgin and Child, Profile

Studies, Technical Sketches,

and Schematic Studies

of Eyes with Visual

Rays,c.1478–80,

silverpoint, leadpoint,

pen and ink, London,

British Museum (1860-

6-16-100r).

C

The

Trustees of the British

Museum/Art Resource,

NY.

he did not get very far. A full knowledge of the function of the eyes’

lenses would only be attained in the mid-nineteenth century, and only

in the late twentieth would a fundamental understanding be realized

of the neurology of visual perception, which, in the case of an infant,

depends not only on the operation of the lenses but on the progressive

chemical sheathing (called “myelination”) of nerve tracks between the

retina and vision-related areas of the cerebral cortex.

As in the Munich Virgin and Child with the Carnation, Leonardo’s

attention to the mechanics of vision in the Hermitage picture has

interesting implications. Leonardo’s artistic contemporaries, such as

Botticelli and Raphael, often treated the theme of divine foreknowl-

edge of the Passion in their Madonnas. The Christ Child is typically

86 The Young Leonardo

Figure 30.

Detail of Schematic

Studies of Eyes with

Visual Rays in fig. 29.

Art Resource, NY.

shown recoiling from, or willingly embracing, a goldfinch or some

other traditional symbol of Christ’s Passion (according to medieval

lore, a goldfinch plucked a thorn from Christ’s crown when he was on

the way to Calvary and was splashed with a drop of his blood – hence,

the characteristic red mark on the bird’s neck). In his two Madonnas,

Leonardo, the empiricist, sought to break down and analyze the phys-

iology of vision and perception, the mysterious connections between

sight and insight. The Munich child is virtually blind, yet seems aware

of the symbolic carnation. The child of the Benois Madonna has still

not responded to the distinctly cruciform shape of the flower (proba-

bly an artistically modified jasmine or wallflower), because he cannot

see it clearly. Once that happens, the child’s hazy curiosity could, pre-

sumably, lead to foresight of his sacrifice. By adding explicit reference

to the act of seeing, Leonardo has protracted and compounded the

tension inherent in portrayals of the Christ Child apprehending his

death. Attuned to Leonardo’s works and interests, Lorenzo di Credi,

in imitation, similarly portrayed babies with underdeveloped vision in

several of his own paintings and drawings.

In contrast to its serious subtext, the Hermitage picture presents

what may be the most joyous and youthful depiction of Mary in