Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

20. The Adoration of the Magi and Invention of the High Renaissance Style 137

Figure 60.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Adoration of the Magi,

1481,penandink

over leadpoint, Paris,

Louvre (RF 1978). Art

Resource, NY.

passions or amore bestiale; in his dialogue, Phaedrus, Plato likened the

soul to a spirited horse, reined in by horsemen or charioteers. These

figures would become, in the painting, the cavalrymen who seem to

be engaged in mock battle – perhaps Leonardo’s fond recollections of

Lorenzo’s and Giuliano’s lavish jousts of 1469 and 1475, full of pomp

and harmless fury. In portraying pagan antiquity, the artist appears

to have consulted as a model an ancient bronze Head of a Horse in

Lorenzo the Magnificent’s collection. Leonardo’s horses here, and in

subsequent works, have that antique sculpture’s exceptionally thick

neck, unnaturally rounded where it joins the crown of the head, and

138 The Young Leonardo

sometimes the distinctive tuft of hair, tied with a cord, at the front of

the mane.

Interestingly, another preliminary compositional drawing for the

Adoration, now in the Louvre, reveals that, at one point in the design

process, Leonardo considered depicting an ancient, sacrificial proces-

sion in the background (fig. 60). Although difficult to decipher, the

parade of small figures moves toward an altar, where a (bovine?) car-

cass has been deposited and pierced with a lance – a scene possibly

inspired by an antique Roman relief. Correspondingly, the Virgin,

in the drawing as in the painting, serves as a central “altar” at which

Christ is worshipped. Thus, the drawing directly associates the blood

ritual of an ancient society with Christ’s sacrifice. On further consid-

eration, Leonardo elected to revise the background subject, perhaps

feeling that his unprecedented gloss made the theme of sacrifice too

explicit, undermining what should be the generally joyous mood of

an Adoration.

21. The Adoration and

Leonardo’s Military Interests

T

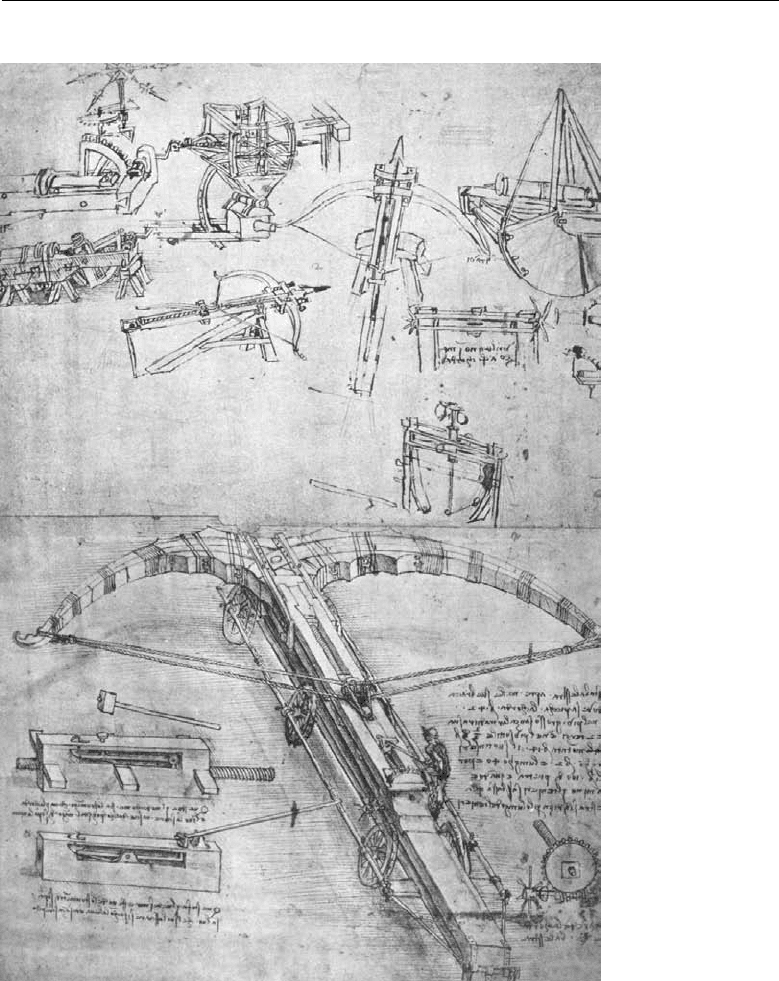

he ultim ate decision to represent sportive combat, rather

than ritual sacrifice, in the Adoration of the Magi (fig. 54) also

may have reflected the artist’s growing military interests. At virtually

the same moment that he conceived the painting, he was devot-

ing much time to the invention of machines of war and defense.

On one page of the Codice Atlantico, he designed a mechanism for

repelling ladders (of attacking soldiers) from a crenellated fortress wall,

not unlike those that surrounded Florence in the Renaissance. On

other sheets, Leonardo contrived huge catapults and colossal crossbows

(fig. 61) – the sprightly, scattered figures that operate those weapons are

similar to the cavalry of the Adoration. For these inventions, he prob-

ably would have studied any designs for war devices left to him by

Martini, reviewed Valturio’s military tracts, and consulted the archi-

tectural treatises of the ancient writer Vitruvius and contemporary

theorist Alberti, which included sections on fortifications and other

defense systems. There is no evidence that any of these ideas ever left

Leonardo’s drawing board. Further, in many instances, what appear to

be plausible machines, conscientiously planned down to the specifica-

tion of bolts and hinges, could not possibly have worked, due to the

intrinsic properties – such as tensile strength and flexibility – of wood

and the other materials involved.

No doubt, Leonardo’s military drawings and research responded to

the unease of Florence’s political situation at the end of the 1470sand

early 1480s. Following the Pazzi conspiracy, the city and surround-

ing areas of Tuscany came to be threatened by the Duke of Calabria,

who commanded the royal armies of Naples. Excommunicated by

Pope Sixtus IV, a Medici foe, Lorenzo the Magnificent found that

his allies, including the dukes of Ferrara and Milan, were reluctant to

139

140 The Young Leonardo

come to his aid. The condemnation had followed an earlier punish-

ment: in 1476, when the Medici contract to control the papal alum

monopoly expired, management of the mines in the town of Tolfa

was turned over to a Roman company. Also in this period, England

had begun to produce its own cloth and was sending less wool to

Florence for processing. Consequently, the Florentine economy had

weakened considerably. Lorenzo may have doubted that he had suf-

ficient resources to field an effective army. An onslaught of plague

further undermined manpower and productivity. When, in the win-

ter of 1479–80, the Duke of Calabria’s soldiers advanced as far as Siena,

where they hunkered down because of inclement weather, Lorenzo

realized drastic action was required. He set off on a dangerous voyage

to negotiate directly with King Ferrante of Naples, arriving in the

southern Italian city around Christmas in 1479.

In Naples, Lorenzo reverted to his usual tactic of spreading

money around liberally – demonstrating his generosity by contributing

dowries for numerous poor girls and buying the freedom of a hun-

dred gallery slaves. He bought Florence’s continued liberty as well,

paying an “indemnity” to the Duke of Calabria and ceding to Naples

some valuable territories in southern Tuscany. During his two and a

half months at the Neapolitan court, the articulate and witty Lorenzo

seems thoroughly to have charmed the king. Although greeted as a

hero upon his return to Florence in 1480, the relief of the populace

was both premature and short-lived; before the year was over, a large

contingent of the Turkish army would threaten the Italian peninsula –

only the first of many threats that would come in waves. In the short

term, the attack of the infidels was a boon to Florence, drawing the

attention and armies of the Duke of Calabria and of the pope away

from Tuscany. However, as many Florentines feared, Lorenzo’s open-

purse diplomacy was not, in the long term, a sound policy, particularly

with respect to much wealthier foreign powers, such as France, which

was always able to enlist a formidable army. Within a dozen years, these

concerns proved to be well founded. Lorenzo’s successor, his politi-

cally inept son Piero, would relinquish the valuable port of Pisa and

other Florentine strongholds to the invading French forces of Charles

VIII in 1494, and an enraged local populace consequently expelled

the Medici.

Perhaps already contemplating his own departure from Florence, in

1481 Leonardo put aside any trepidation he had and focused intensely,

21. The Adoration and Leonardo’s Military Interests 141

Figure 61.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Design for a Colossal

Crossbow,c.1481,

pen and ink, Milan,

Biblioteca Ambrosiana,

Codice Atlantico (149r).

Art Resource, NY.

for a time, on the Adoration of the Magi. Ingeniously, he was able to

unify the epic range of activities – military as well as devotional –

through the geometries he imposed on the dense composition as

well as the comprehensive way in which he patterned it in light and

dark. This was a decisive break from the traditional Florentine method

of painting, which involved adding, coloring, and modeling in light

and shadow each figure or element, one at a time. Leonardo’s novel

142 The Young Leonardo

approach here was to conceive the entire work as he would a large

study in pen, brush, and wash, broadly determining the placement of

the strongest lights and darks, and a few of the medium tones. By this

means, indicative of the comprehensive manner in which his mind

grasped the matter before it, he achieved an unprecedented coherence

in Renaissance painting, in terms of both design and idea, emphasizing

certain figures and symbols, suppressing others – an internal dialogue

in black and white. In this working method, color became almost an

afterthought, an embellishment on a rigorously intellectual scheme.

Only after countless revisions to his composition would Leonardo

introduce, as final touches, “superficially” attractive elements of color

and dashes of spontaneity – just as, only after careful preparations and

contributions by others, had he placed the finishing glint or sparkle

on a Verrocchio-shop picture. This form-over-color approach was

in accord with notions espoused by the Neoplatonists, particularly

Ficino, who wrote in his treatise, “On the Immortality of the Soul,”

that “sight cannot perceive colors unless it assumes [first] the forms

of these colors.” That is, color has no reality independent of a solid

object.

Powerful as the Adoration of the Magi was in its unfinished state,

Leonardo’s failure to consummate it must have displeased not only the

patrons but also his supportive father. Eventually, the S. Donato monks

were able to hire the painter Filippino Lippi, illegitimate son of Fra

Filippo by the nun, Lucrezia Buti, to take over the commission, and

he wisely availed himself of Leonardo’s drawings in creating his own

altarpiece, completed in 1496. No doubt glad to be relieved of the

long moribund project, Leonardo, then living in Milan, would have

gratefully instructed his father to donate his designs to Lippi, who had

earlier executed the altarpiece for the Palazzo della Signoria, when

Leonardo did not follow through on that work.

How Ser Piero, probably mortified, handled the S. Donato situa-

tion is not known. Leonardo, too, must have felt some embarrassment

along with regret, for by that time his rival and former colleague, an

artist of more limited talents, Perugino, had attained a sterling reputa-

tion and important patronage in Rome. He had executed a fresco for

Pope Sixtus IV in Old Saint Peter’s basilica around 1479, and he was at

work, at the pontiff ’s behest, on his monumental fresco, Christ Giving

the Keys to Saint Peter (c. 1480–82), in the Sistine Chapel. Impressive in

its spatial grandeur and narrative clarity, the work was, in truth, hardly

21. The Adoration and Leonardo’s Military Interests 143

more advanced than Leonardo’s juvenile Annunciation with respect to

the individual figures, the bland, facial expressions and stilted poses of

which were all too characteristic of Perugino’s conservative manner.

Nevertheless, although he was one of the younger artists participating

in the decoration, Perugino seems to have been authorized to devise,

with Botticelli, the overall scheme of the room, the most prestigious

project in Christendom at that time.

Meanwhile, Leonardo’s abandoned Adoration languished in the

house of his friend, Giovanni de’ Benci, the brother of Ginevra, and

later passed to Giovanni’s son, Amerigo. The contract for the altar-

piece had stated that the work was to be completed in twenty-four

months, thirty at most – a stipulation that, in hindsight, Leonardo

must have found infinitely amusing, both in light of his work habits

and the S. Donato monks’ resources. Very tight with funds, the monks

had asked Leonardo, contrary to custom, to spend his own money on

materials, rather than giving him an advance, and their last payments

to the artist had been in wine rather than cash.

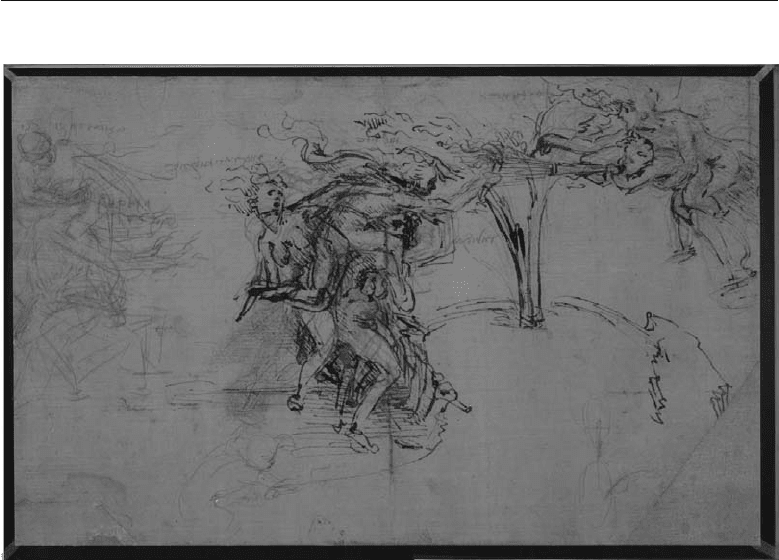

22. Leonardo and Allegorical Conceits

for the Medici Court

O

n the reverse of a sheet of “old seer” studies for the

Adoration, Leonardo furiously sketched an allegory that

deserves careful attention for what it may disclose about his rela-

tionship with Lorenzo de’ Medici in the early 1480s. The design

and theme, involving personifications of Fortune, Death, Envy, and

Ingratitude – all clearly labeled – would seem to be the artist’s own

inventions (fig. 62). As in most of Leonardo’s “left-handed” narra-

tives, the electric action flows from right to left. At far right, Fortune

(Fortuna), depicted as a woman with long, flowing hair, holds a child,

who blows a trumpet to extinguish the torch of Death (Morte), intent

on setting the branches of a tree on fire. Supporting Death on their

shoulders are the surprised figures of Envy (Invidia) and Ingratitude

(Ingratitudine). Roughly indicated at left, Ignorance (Ignoranza)and

Pride (Superbia), apparently complicit in the attempted arson, watch

in dismay as their plot is foiled.

A recent suggestion that the allegory alludes to the failed assas-

sination attempt on Lorenzo de’ Medici is intriguing. The drawing,

related in style to the highly charged background of the Adoration,

probably dates to the period of 1481–82, some time after Lorenzo

had returned to Florence from his successful diplomatic meeting in

Naples and after almost all of the prime conspirators in the Pazzi

scheme, including Baroncelli, had been caught and executed. The ink

sketch also may have followed the shocking revelation of yet another

plot to murder Lorenzo in 1481. The tree, according to this line of

speculation, would be a laurel, the hardy plant that Lorenzo took as his

personal emblem and that subsequently became a symbol of Medici

endurance and dynasty. When not writing about laurels and other

natural elements in his poetry, Lorenzo often featured Fortuna as a

145

146 The Young Leonardo

Figure 62.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Allegory with Fortune and

Death,c.1481,metal-

point, pen and ink with

wash on pink prepared

paper, London, British

Museum (1886-6-9-42).

C

The Trustees of the

British Museum/Art

Resource, NY.

principal theme. Therefore, Leonardo may have created the drawing

to demonstrate his loyalty and to curry favor with the beleaguered

Lorenzo, for whom he would have provided the captions (although

written in reverse, easily read), a most atypical concession on the artist’s

part.

It is perhaps of some significance that the extinguished-flame motif

recollects and transforms the theme that Sandro Botticelli employed

six years earlier in his standard for Giuliano’s joust. In contriving the

allegory, Leonardo may have felt that he was competing for attention

with Botticelli, who, by that time, had probably already begun to con-

sult with Medici court literati about the content of his mythological

paintings of Primavera (Spring) and Pallas and the Centaur, commis-

sioned by Lorenzo’s second cousin, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco (both

pictures now in the Uffizi). In Leonardo’s mind, the award to Botti-

celli of the contracts for those major works may have signaled that his

colleague was solidifying his position as the Medici family’s painter of

choice. The allegories were to serve as decorative centerpieces for the

household the patron would soon establish with a new wife.

More disconcerting still for Leonardo would have been the real-

ization that Botticelli, a tanner’s son, was the favored artist for pictures