Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

25. Saint Jerome 167

such like beasts – turning straight from nature to his art,

began to draw on the rocks the movements of the goats

which he was tending, and so began to draw the figures

of all the animals which were to be found in the country,

in such a way that after much study he not only surpassed

the masters of his own time but all those of many pre-

ceding centuries. After him art again declined, because all

were imitating paintings already done; and so for centuries

it continued to decline until such time as Tommaso the

Florentine, nicknamed Masaccio, showed by perfection of

his work how those who took as their standard anything

other than nature, the supreme guide of all the masters,

were wearying themselves in vain. Similarly I would say

about these mathematical subjects [contemporary paint-

ings heavily reliant on mathematical ratios and perspective

constructions] that those who study only the authorities

and not the works of nature are, in art, the grandsons and

not the sons of nature, which is the supreme guide of the

good authorities.

Leonardo’s views appear to have been influential, because the three

watershed periods of art that he defines exactly coincide with those

later identified by Vasari in his Lives of the Artists. There Giotto’s

work replaced the maniera greca of Byzantine-influenced, Italian art;

the painter Masaccio “swept away” the manner of Giotto (Ghiberti is

seen as the pivotal figure in sculpture); and Leonardo is saluted as the

creator of the “modern” style.

Interestingly, the specific touchstone for Leonardo’s Saint Jerome

was not, it seems, a renowned fresco or major altarpiece but, perhaps,

a small, illuminated initial by Francesco d’Antonio del Cherico on a

page in a mid-fifteenth-century manuscript version of Jerome’s Letters

(Epistulae) in the Medici collection. The illuminator presented the

saint, within the letter “D,” in much the same pose and before the

customary, rocky outcropping. Only the position of the right leg and

the hairstyle of the saint have been altered in Leonardo’s painting; he

was given the typical, bald head of Verrocchio’s St. Jerome. Leonardo’s

paraphrase would have flattered Lorenzo, the current owner of the

manuscript (purchased by his father, Piero), in acknowledging the

beauty and authority of the treasured work.

168 The Young Leonardo

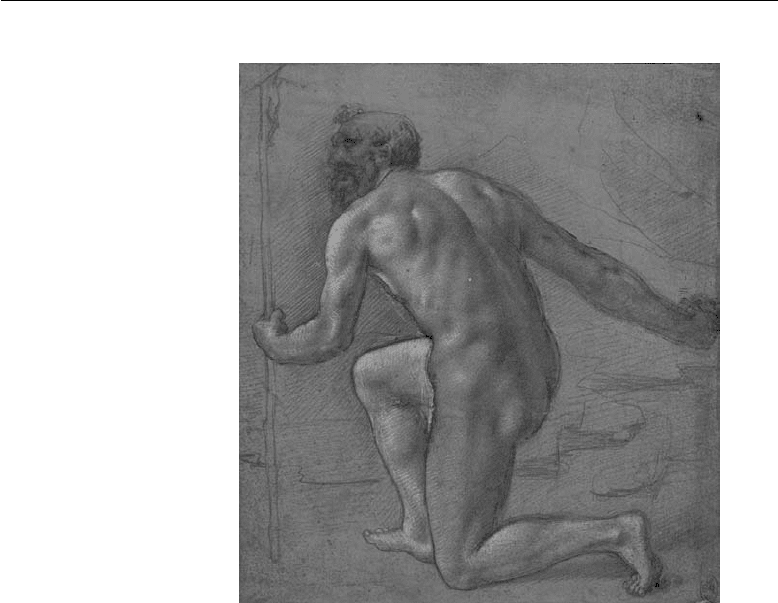

Figure 72.

Workshop Assistant,

after Leonardo da

Vinci, Study of a Studio

Model for Saint Jerome,

c. 1480–82?, silverpoint,

heightened with white,

on purple-gray prepared

paper, Windsor Castle,

Royal Library (12571).

The Royal Collection

C

2010 Her Majesty

Queen Elizabeth II.

Leonardo’s probing exploration of Jerome’s muscle and bone

structures reveal his growing interest in human anatomy and causes

one to suspect that, by this time, he had had the opportunity to exam-

ine cadavers – perhaps some dissected by the brothers Pollaiuolo. It is

unlikely that he performed the dissection of a corpse, himself, until

two decades later, after he returned to Florence from Milan in the

early sixteenth century, and conducted an autopsy on a gentleman

said to have died a centenarian. Moreover, by imitating another of the

Pollaiuloli’s famed workshop practices, Leonardo was able to achieve

the very volumetric, sculptural quality of his figure of Jerome. That is,

like the brothers, he drew a posed studio model from both front and

back to understand better, one might say “stereometrically,” the struc-

ture of the body and its orientation in space. We know this because

there exists a copy after a lost drawing by Leonardo (fig. 72)that

shows his model for Jerome from behind, in basically the same pose

as the painted saint except for the turn of the head. In Renaissance

studio practice, the model used a pole to help him keep his left arm

raised for long periods. Were it not for the right-handed slant of the

hatching, the study, by an unidentified Leonardo assistant, could easily

25. Saint Jerome 169

be mistaken for the master’s – the drawing, otherwise, so scrupulously

follows the style of original.

Although Jerome’s facial type recalls Verrocchio-school depictions

of the saint, and the Pollaiuoli no doubt provided inspiration and mod-

els, Leonardo’s penitent recalls most strongly, in spirit, the sculptures

of Donatello. Above all, the Jerome finds its ancestry in Donatello’s

cadaverous Saint Mary Magdalene (now in the Museum of the Duomo,

Florence), a wooden sculpture of sublimely simulated decay. Leonardo

similarly portrays spiritual release through denial of the flesh – fasting

and abstinence – and, following Donatello, presents the saint as if he

had been weathered by elemental forces, the same forces responsible

for the ravaged landscape.

26. First Thoughts for the Virgin of

the Rocks and the Invention of

the Mary Magdalene-Courtesan Genre

A

lthough the painting was never fully realized, saint

Jerome’s densely compact pose attained an important status

in Leonardo’s mind. The artist continued to improvise on the gesture

in several future works, particularly his two versions of the Virgin of

the Rocks, where it evolved (as can be easily traced in his drawings;

see figs. 65 and 73) into the inclusive, sheltering pose of Mary and

where Leonardo’s mysterious, geological formations reappeared as well

(fig. 74). Infrared-light examination of the second Virgin of the Rocks

(now in the National Gallery, London) reveals some relevant chalk or

charcoal drawing on the panel, beneath the paint layers; these outlines

indicate that, before picking up his brush, Leonardo briefly considered

a pose for Mary that was very close to Jerome’s.

Recycled from the Saint Jerome, the tall, cavernous stone formations

in the Virgin of the Rocks would have taken on new meanings in their

new context – metaphorical allusions, traditionally associated with

Mary, from the biblical Song of Songs (2:14):

My dove in the cleft of the rock, in the cavities of walls,

reveal your countenance to me.

One suspects that the painting may also reflect, in its crepuscular

moment, seemingly haunted by the vestiges of rain clouds, other lines

from that passage:

for lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone. The

flowers appear on the earth, the time of singing has come –

until the day break and the shadows flee away, turn my

beloved, and be thou like a roe or a young hart upon the

mountains –. (2:11–12 and 17)

171

172 The Young Leonardo

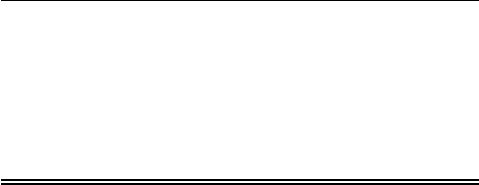

Figure 73.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Detail of Sheet of Sketches

with a Nativity,c.1481–

82, metalpoint with pen

and ink on pale blue

prepared paper, Windsor

Castle, Royal Library

(12560). The Royal

Collection

C

2010

Her Majesty Queen

Elizabeth II.

In the spirit of these verses, Leonardo’s holy figures miraculously

materialize in quiet isolation, as if the first life on earth, with the

secret, sudden existence of lilies and deer. This is the time of day and

climate that the artist recommended in his Treatise on Painting,saying

in one place that “it is better to make [landscapes] when the sun is

covered by clouds, for then the trees are lighted up by the general light

of the sky and the general shadows of the earth”; and in another “you

should make your portrait at the hour of the fall of the evening when

it is cloudy or misty, for the light is then perfect.” In the Mona Lisa,

this worked to sympathetic effect. In its muted twilight, the brooding

26. First Thoughts for the Virgin of the Rocks 173

Figure 74.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Virgin of the Rocks,

1483–c. 1486,oilon

panel, Paris, Louvre.

R

´

eunion des Mus

´

ees

Nationaux/Art

Resource, NY.

Virgin of the Rocks harks back, beyond the Saint Jerome, to Filippo

Lippi’s strange and obscure Adoration for the old Cosimo (fig. 2).

Not long before leaving Florence for Milan, Leonardo seems to

have begun to plan a painting of yet another single saint, a half-length

174 The Young Leonardo

portrayal of Mary Magdalene. Given his difficulties with complet-

ing time-bound, contractual commissions, one wonders whether he

began to consider producing such small pictures on speculation. This

was not a common practice in Florence at that time, but he was con-

cerned about an income: as we previously noted, Ser Piero had cut

off Leonardo’s “allowance” by 1480. He would not receive an inheri-

tance for some twenty-seven years – only after the death of his uncle

Francesco in 1507 and the resolution of an acrimonious lawsuit against

his seven half-brothers over the estate. A notary half-brother managed

to prevent Leonardo from receiving anything from his father, who died

intestate in 1504, but failed to keep the artist from inheriting a farm

and money from his uncle. That a possibly cash-strapped Leonardo

would consider such a speculative sales strategy is corroborated by

remarks he made later in a manuscript:

But see now the foolish folk! They have not the sense

to keep by them some specimens of their good work so

that they may say, “this is at a high price, and that is at a

moderate price and that is quite cheap,” and so show that

they have work at all prices.

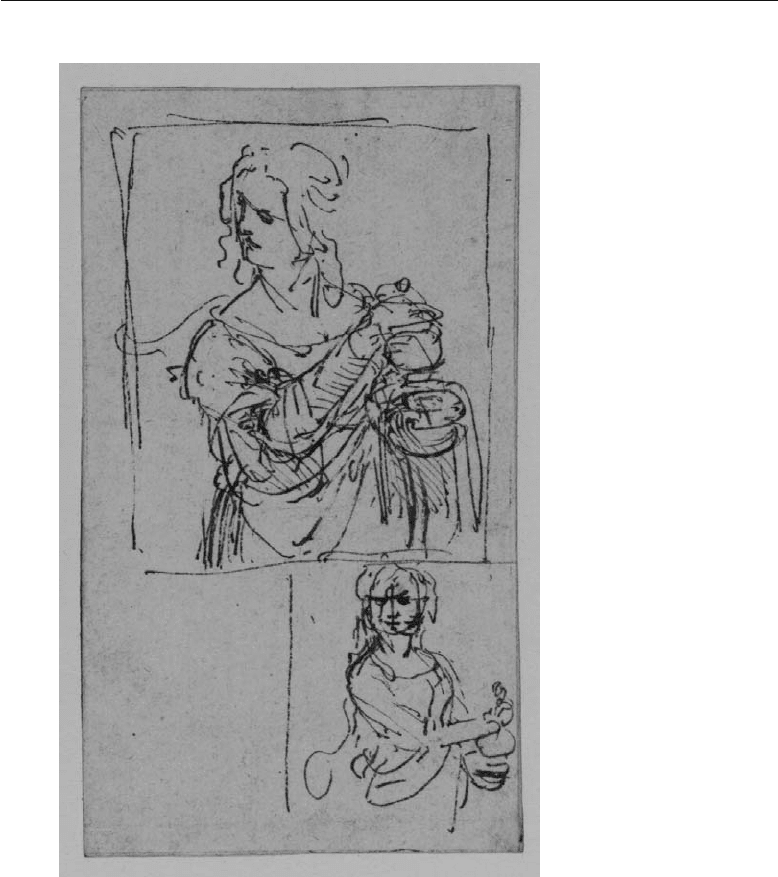

Probably around 1481–82, Leonardo made two rapid, pen-and-ink

sketches (on a sheet now preserved in the Courtauld Institute Gallery,

London) of the Magdalene holding or opening a jar of unguent –

her traditional attribute, given that the Bible relates that she, among

Christ’s closest Galilean followers, anointed his feet with oil (fig. 75).

Although half-length pictures of her would become common

throughout Italy in the sixteenth century, in the Quattrocento such

representations were rare, confined almost exclusively to multipaneled

triptychs or polyptychs in which she is only one of several holy figures.

In fact, Leonardo’s idea, to present her in an independent, half-length,

“portrait” format, may be without precedent.

Although his studies are summary, one can discern that he wished

to show the Magdalene not as a haggard penitent, as Donatello had

done, but as the wealthy, promiscuous young woman turned prosti-

tute, described in the Golden Legend. His Mary wears sumptuous layers

of clothes, her hair is tousled, locks straying, and she grasps what looks

to be an elaborate and expensive jar. Her kind expression, barely indi-

cated, is that of the dulcis amica dei, the “sweet friend of God,” as the

amorously inclined Petrarch described her. Undoubtedly, the affluent

26. First Thoughts for the Virgin of the Rocks 175

Figure 75.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Studies of Saint Mary

Magdalene,c.1481–82,

pen and ink, London,

Courtauld Institute

Gallery. The Samuel

Courtauld Trust, The

Courtauld Gallery,

London.

classes that purchased pictures, almost continuously expanding in

Florence throughout the Renaissance, would have more easily iden-

tified with this cordial, splendidly garbed Magdalene type.

The metamorphosis of Mary Magdalene from wretched hag to

beautiful companion of the Lord could only have occurred in the

time and place that it did. From the high-minded deliberations of the

Florentine Neoplatonists over the concepts of love and ideal pulchri-

tude emerged a veritable celebration of female beauty – vanquishing

centuries of medieval misogyny, during which a lady’s attractiveness

was suspiciously regarded as a lustful trap, an instrument of the devil.

176 The Young Leonardo

Ficino’s elevated notions of amore platonico and of corporeal beauty as

a reflection of divinity filtered down into popular culture and, by the

beginning of the next century, engendered a publishing efflorescence

of love poems and sonnets. The nostalgia for chivalry, particularly

strong in the court of Lorenzo the Magnificent, also helped this cult

of feminine beauty to thrive.

Consequently, there came to be a change of emphasis in the

Magdalene’s story; where once she had been seen primarily as a victim

of sin, visibly stigmatized, now her spiritual journey and awakening

were regarded as life affirming and her inner beauty made mani-

fest. In 1528, the new, positive view and treatment of women was

authoritatively codified in Baldessare Castiglione’s famous manual of

court manners and decorum, The Book of the Courtier, an imaginary

conversation between Lorenzo de’ Medici’s youngest son, Giuliano,

and other magnanimous gentlemen. Castiglione portrays Giuliano as

a passionate champion of women, putting words into his mouth that

have a curiously modern ring:

– tell me, why has it not been established that a dissolute

life is quite as disgraceful in men as it is in women? – if you

will acknowledge the truth, you surely know that of our

own authority we men have arrogated ourselves a license,

whereby we insist that in us the same sins are most trivial

and sometimes deserve praise which in women cannot be

sufficiently punished, unless by a shameful death, or at least

perpetual infamy.

It must remain an open question as to whether Leonardo was respond-

ing in his seemly conception of the Magdalene only to such larger

cultural influences or whether the sin and sexual disgrace of his mother

also affected his views.

Leonardo appears to have waited until he returned to Florence

from Milan in 1500 before developing his “lovely Magdalene” con-

cept further. That year was a Jubilee or Holy Year (Anno Santo), which

meant the Church offered special opportunity for penance: the con-

trite could receive exceptional indulgence, fully cleansing them of sin.

In this atmosphere of atonement, there were external, often very pub-

lic displays of remorse, and famous penitents, such as the Magdalene,

were particularly recalled and revered. During this period, Leonardo

may well have shared his designs (some much more advanced than the