Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

5. First Works in Florence and the Artistic Milieu 37

He meticulously differentiates the layers of stratified rock that com-

prise the cliff’s face and traces or implies the flow of water from hilltop,

down waterfall, to valley stream, to town and verdant, saturated fields.

Whether the artist was able to translate his dramatic landscape into

paint and insert it into the background of one of the Verrocchio shop

pictures, the likely purpose of the study, cannot be determined; the

view does not reappear in any of Verrocchio’s or Leonardo’s extant

paintings. He may well have been following the lead of Piero Pol-

laiuolo, perhaps the first Florentine painter to include in his pictures

recognizable views of the Arno valley below the city, as in his Annunci-

ation of c. 1470, now in Berlin. Whatever its intended use, Leonardo’s

drawing is especially interesting in that it reveals how, even in his

youth and when making a dated “record,” he tended to idealize,

almost automatically, the subject before him.

6. Early Pursuits in Engineering –

Hydraulics and the Movement of Water

P

erhaps in the early 1470s, and certainly by the end of

the decade, Leonardo became very interested in the move-

ment of water through man-made, technical means. Vasari states that

Leonardo, when “still a youth,” was the first to suggest reducing the

unpredictable river Arno to a navigable canal from Pisa to Florence.

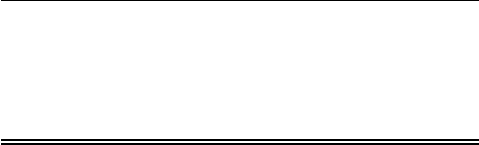

The earliest pages (c. 1478–80) of Leonardo’s Codice Atlantico are

covered with devices for raising large quantities of water or directing

its flow. Some sheets credibly illustrate systems of weirs and locks on

canals; others have studies of contraptions with gears, weights, and

hydraulic cylinders, such as the so-called Archimedes’ screw, based on

the ancient Greek mathematician’s famous invention, which suppos-

edly employed a large revolving spiral to pull water upward (fig. 7).

Although Leonardo’s writings indicate that he sometimes consulted

treatises on water in Lorenzo the Magnificent’s possession, the latter

seems not to have kept in his library any books by Archimedes or

Heron of Alexandria, the two standard, classical sources on hydrostat-

ics and pneumatics. However, Leonardo probably saw a copy of the

Italian humanist Roberto Valturio’s De re militari (1472), an anthol-

ogy of ancient military science, which illustrated the hydroscrew and

other devices for the conveyance of water. The artist would eventually

obtain his own version of this text.

Leonardo may have received important early encouragement in

his engineering interests from the multitalented Francesco di Giorgio

Martini, a Sienese painter, manuscript illuminator, sculptor, architect,

and military engineer. In 1472, Martini’s appointment as Siena’s operaio

dei bottini, that is, civil engineer for (water) conduits, was terminated,

and he was freer to travel and to pursue his career as a painter. Circum-

stantial evidence indicates that he probably spent extended periods in

39

40 The Young Leonardo

Florence between 1472 and 1474. Rather tentative in style and exe-

cution, his pictures from around (and after) that time show the strong

influence of the progressive, Florentine artists Alesso Baldovinetti,

Botticelli, Lippi, and, especially, Verrocchio – Martini’s attempts to

give his provincial works a veneer of modernity. His Coronation of the

Virgin, painted around 1472–74 (now at the Pinacoteca Nazionale,

Siena), owes much to Verrocchio, and some of his sculptures from

that time have been mistakenly attributed to either Verrocchio or

the young Leonardo. More highly regarded for his designs for mar-

itime projects and for military machines and fortifications, Martini

would have been able to offer to the twenty- or twenty-one-year-

old Leonardo instruction in large-scale engineering projects – and a

professional role model – that Verrocchio could not. His machine

drawings of the 1470s represent many of the same sorts of devices that

the young Leonardo would try to design: hoists, pumps, hydraulic

lifts, and mechanical maritime structures.

After his time in Florence, the Sienese inventor may have inter-

mittently kept in touch with Leonardo for a number of years, because

his many projects kept him traveling constantly, occasionally through

Tuscany. One should also bear in mind that, during those periods that

he was based in his native Siena, he could journey to Florence in a

day (or Leonardo to Siena), from dawn to dusk, on a good horse.

Eventually, he and the young man from Vinci would have recon-

nected in Milan, after Leonardo moved there; and we know that,

in 1490, the two men were together in the nearby town of Pavia,

advising on structural matters concerning the cathedral. They agreed

on many architectural principles, advocating that the ideal church

design should have a central plan (that is, entirely symmetrical with

longitudinal [nave and choir] and latitudinal [transept] structures of

equal length), and they shared a strong Aristotelian bias for “organic”

proportions, derived from natural forms.

At some point, Leonardo came to possess some of Martini’s impor-

tant manuscripts on architecture and engineering. These manuals were

of immense value to him, because, over the course of his career,

he would support himself more through defense and public-works

projects than through his artwork. Leonardo’s own, eloquent mechan-

ical illustrations were indebted to Martini’s, which offered examples

of exploded or cutaway views and depicted how machinery moved

and operated in three-dimensional space. These were immediately

6. Early Pursuits in Engineering – Hydraulics and the Movement of Water 41

Figure 7.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Devices for Raising Water

(including the Archimedes’

Screw) and Other Studies,

c. 1480,penandink,

Milan, Biblioteca

Ambrosiana, Codice

Atlantico (1069r).

Art Resource, NY.

comprehensible and credible images for which written commentary

was almost unnecessary.

The young Leonardo concerned himself not only with macro-

engineering schemes, with how the flow of water could be diverted,

controlled, and its power harnessed, but also with how people could

travel over and under it. He was probably familiar with Lorenzo de’

Medici’s copy of Flavius Vegetius Renatus’ De re militari (On Mat-

ters Military), a fourth-century treatise that emphasized the need for

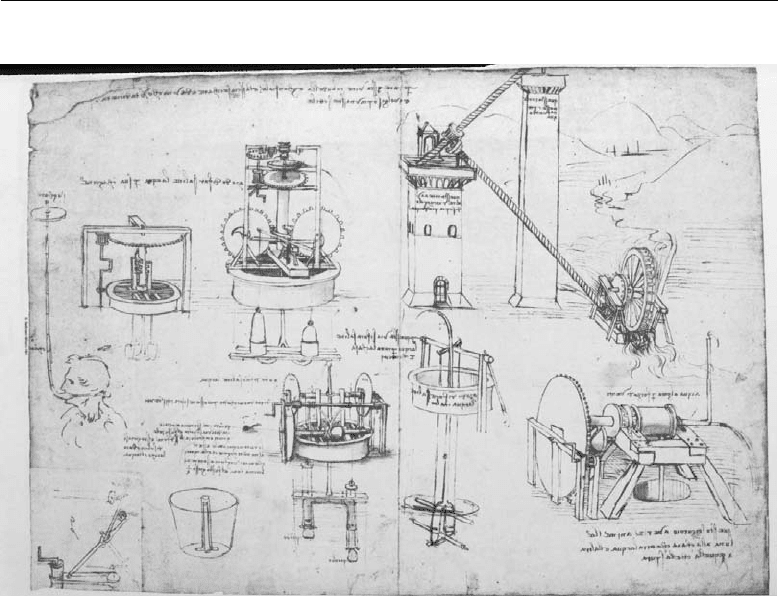

Roman soldiers to know how to swim. On one sheet (fig. 8), the

artist drew, in succession at upper left, prototypes for a snorkel with a

long breathing hose (perhaps for clandestine military activities), swim-

ming goggles (which Leonardo says were used, along with breathing

tubes, by pearl fishers in the Indian Ocean), and water “shoes” –

small, rounded boards attached to the feet – and water-shoe poles.

The obvious impracticality of this last invention leads one to suspect

that it was based solely on imagination and not experimentation.

Like so many of Leonardo’s inventions, the water-walkers and poles

could function only on paper; he seems often to have appreciated an

idea or theory for its beauty, its delightfulness, without concern for

42 The Young Leonardo

its efficacy or validity. However, another aquatic design he produced

at that time, for a lightweight, portable bridge for military excursions,

would appear to operate in the real world. Later, he would develop and

advocate the breathing tube as a built-in component of a plausible,

flotation outfit, a lifesaving device for soldiers and other shipwreck

victims:

it is necessary to have a coat made of leather with a double

hem over the breast which is the width of a finger, and

double also from the girdle to the knee, and let the leather

of which it is made be quite air-tight. And when you are

obliged to jump into the sea, blow out the lappets of the

coat through the hems of the breast, and then jump into

the sea. And let yourself be carried by the waves, if there is

no shore near at hand and you do not know the sea. And

always keep in your mouth the end of the tube through

which the air passes into the garment; and if once or twice

it should become necessary for you to take a breath when

the foam prevents you, draw it through the mouth of the

tube from the air within the coat.

When Leonardo investigated a natural phenomenon, such as a

violent, tossing wave or an optical illusion, he did so with relentless

diligence. Often, his inquiry was prompted by an observation that

he found particularly intriguing or inexplicable. He wondered, as we

might today when looking into the rearview mirror of an automobile,

“why something seen in a mirror appears smaller than it [really] is?”

Then, he would ask, “what sort of a mirror would show the thing

exactly the right size?” On another day, he might ponder why “a dead

woman floats face downward in the water, and a man the opposite

way [?]” When faced with such conundrums, his immediate response

was to try to make comparisons with other natural phenomena he had

observed and to draw analogies, be it the reflection of the moon in a

pond or the drifting orientations of inanimate objects on a river.

Given time and opportunity, he would consult “authorities” –

Aristotle, Euclid, or Pliny – to see whether they provided answers, in

the scant books and manuscripts available to him through the Medici,

friends, or even the kindness of bibliophile strangers, such as those sec-

ondhand acquaintances he describes as “the nephew of Gian Angelo

the painter [who has] a book about water that belonged to his father”

and “the brother of Sant’ Agosta in Rome – who lives in Sardinia.”

6. Early Pursuits in Engineering – Hydraulics and the Movement of Water 43

Figure 8.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Devices for a Diver,

for Walking on Water,

and Various Studies

for Machines,c.1480,

pen and ink, Milan,

Biblioteca Ambrosiana,

Codice Atlantico (26r).

Veneranda Biblioteca

Ambrosiana.

In the end, even if he could not completely comprehend or explain

what he saw, he at least attempted to address it in practical terms; he

would try to invent a nondistorting mirror or create an apparatus to

prevent drowning. This is not to say that Leonardo would not permit

himself, on occasion, to indulge in some “useless” abstract thought or

theory, as in his brain-twisting and nihilistic little romp:

Among the greatest things that are found among us, the

existence of Nothing is the greatest of all. This dwells in

time, and stretches its limbs into the past and the future,

and with these takes to itself all works that are past and

those that are to come, both of nature and of the animals,

and possesses nothing of the individual present. It does,

however, extend to the essence of anything.

Leonardo’s tendency, seen already in his View of the Arno,to

idealize or to “correct,” to bring what he observed into accord

with preconceived notions or theory, profoundly affected almost

every project and investigation he undertook throughout his life.

44 The Young Leonardo

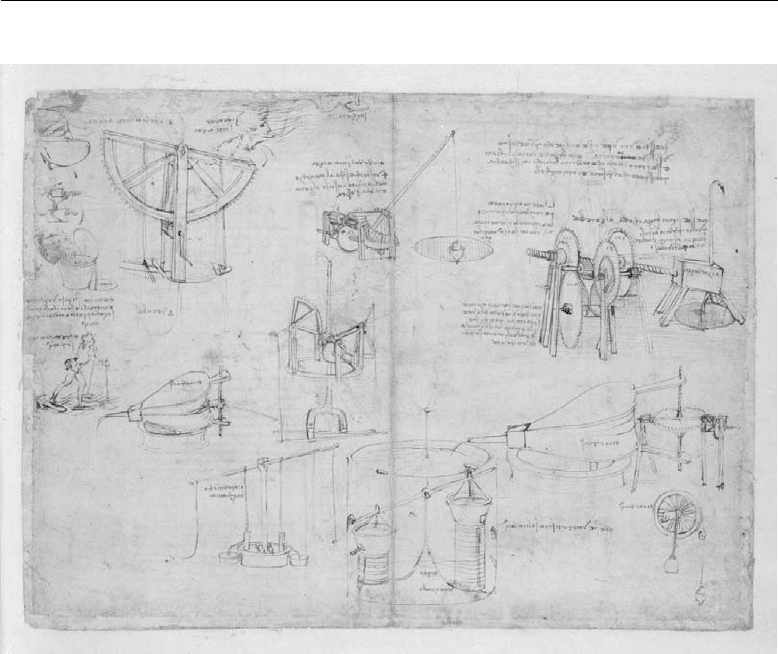

Figure 9.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Cross-Section of a Man’s

Head, Showing Three

Chambers for Reception,

Processing, and Storage

(Memory) of Sensory

Impressions,c.1493–95,

pen and ink, Windsor

Castle, Royal Library

(12603r). The Royal

Collection

C

2010

Her Majesty Queen

Elizabeth II.

Hyperinquisitive as he was, he was never a scientist in the mod-

ern sense – methodically setting up controlled trials and accurately

measuring and recording the results, a modus operandi developed in

the late seventeenth century. His fascination with water had much to

do with the fact that he held the ancient (and contemporary) view

that it was one of the four basic elements, along with air, earth, and

fire and constituted the most vital fluid of what he described, in his

famous personification, as the “Body of the Earth.”

Like all of us, when confronted with evidence that contradicted

theory, he tended to cling to the latter, going so far as to disbelieve –

and reconfigure in his drawings – what was placed directly before his

eyes. For example, he had the opportunity to examine closely a human

brain (and those of many animals), and yet, when he drew the organ

in cross-section, he delineated an imaginative, three-chambered cog-

nitive system (fig. 9), based on the capricious speculations of medieval

6. Early Pursuits in Engineering – Hydraulics and the Movement of Water 45

scholars interpreting the ancient writings of Aristotle, particularly his

treatise On the Soul (De anima). To put it another way, Leonardo acted

as if what he observed in many instances – if it departed from accepted

notions – constituted an anomaly. In his startling, cross-section view of

a couple copulating (Windsor Castle, Royal Library), Leonardo traced

the origin of the sperm, back through a quirky, reproductive plumb-

ing system, not to the testicles, but, again following Aristotle (and

Hippocrates), to the spinal column and ultimately to the base of the

brain. The artist inventively drew a long duct that directly connected

penis to spine. Leonardo would have known not only Aristotle’s faulty

biological scheme but also Diogenes Laertius’ memorable aphorism,

“semen is a drop of the brain.” Lorenzo de’ Medici had a copy of

the Greek biographer’s third-century Lives of the Philosophers translated

into the vernacular. Similarly, because of his generally mechanistic

approach, when Leonardo later made a detailed study of the human

heart, during a dissection, he could not resist adjusting his illustration

slightly, regularizing the geometry, to bring it into conformity with

ideal, mathematical, and engineering principles.