Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

3. The Cultural Climate of Florence

C

osimo’s p atron age of the visual ar ts was no less impressive

than his support of humanist scholars and literature. Under his

bullish, benevolent reign, Filippo Brunelleschi created the vast dome of

the cathedral, an architectural miracle, and the sculptor Lorenzo Ghib-

erti realized the sumptuous gilt bronze Gates of Paradise for the Baptis-

tery portal nearby. While Brunelleschi built for Cosimo what would

become the principal Medici church, San Lorenzo, the dependable

architect Michelozzo di Bartolomeo, at Cosimo’s request, renovated

the church and convent of San Marco (where Cosimo maintained a

penitential cell), constructed a grand new palace for the Medici on the

via Larga, and renovated villas for them in the sylvan backwaters of

Cafaggiolo, Careggi, and Trebbio. From his favorite artist, the sculptor

Donatello, Cosimo commissioned several important works, including

the controversial, sensuous bronze David, a rakish interpretation of the

biblical hero, with more sashay than swagger.

Cosimo kept busy the rambunctious Fra Filippo Lippi, seducer

of ladies and nuns alike, and all of the other major painters as well;

Lippi supplied a number of pictures for the new Palazzo Medici,

and Fra Angelico and Paolo Uccello painted altarpieces and frescoes

for the churches of San Marco and Santa Maria Novella. Some of

Lippi’s pictures, such as his Annunciation (c. 1439) in San Lorenzo,

followed what were the latest, progressive, “scientific” trends in art. He

defined the space of the painting through a strict, if vertiginous, one-

point perspective system – a striking application of mathematics and

geometry – and he rendered the foreground glass vase with impressive,

optical precision.

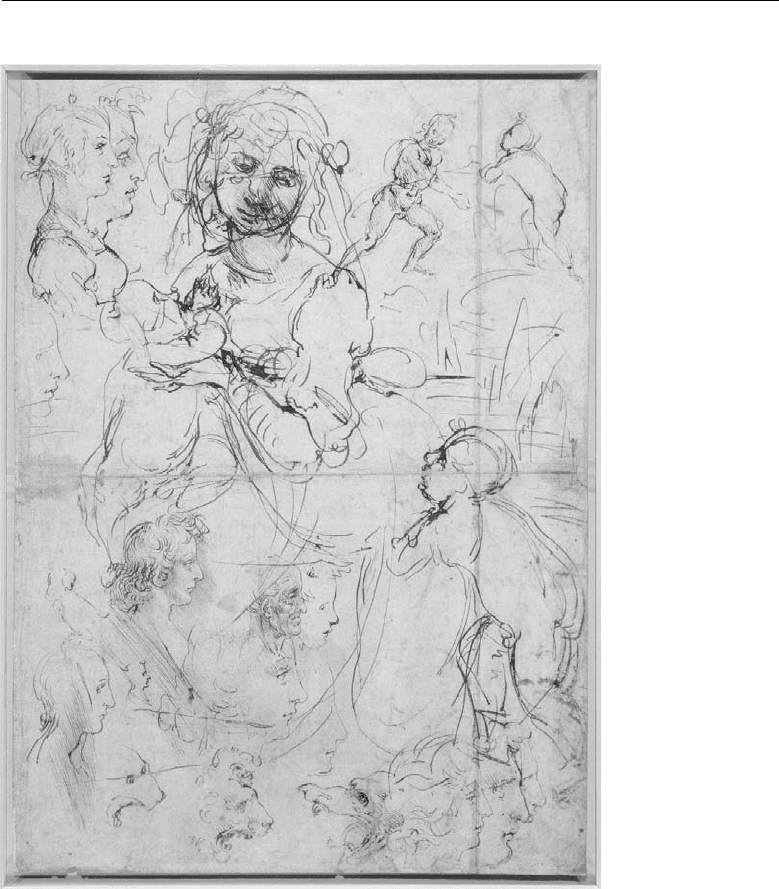

Other of Lippi’s works, among them the Adoration of the Christ

Child that he created for Cosimo’s personal chapel in the Medici palace

17

18 The Young Leonardo

(and a very similar picture for the private retreat of his profoundly

religious and cultured daughter-in-law, Lucrezia Tornabuoni), per-

petuated a mystical strain in Florentine painting (fig. 2). That darkly

suggestive work presents a visionary experience. The holy personages

are lost in contemplation; individual blossoms and natural elements

have an acutely alive and symbolic presence; the feral, rocky land-

scape and heavens less a setting than an enveloping cloak, hermetically

sealing off the back of the work. Lippi has re-created a mystical reve-

lation of the twelfth-century saint Bernard of Clairvaux, shown in the

background of the palace painting (now in Berlin), who, according

to legend, had a vision of the Nativity when he was a child. Signifi-

cantly, Leonardo seems to have found this introspective, artistic trend,

with its strange remoteness, as compelling as the new “rational” and

mathematic mode of Florentine painting.

Although much of this creative activity had been completed by

the time Leonardo and his father had reached Florence, the young

boy would have seen ongoing projects instigated by Cosimo’s son,

Piero the Gouty, and, later, his grandson, Lorenzo the Magnificent

(Il Magnifico). Upon his arrival, Leonardo would have been dazzled

by the opulent marble and porphyry tomb for Cosimo that his future

master Andrea del Verrocchio created and later erected in 1465 in San

Lorenzo and by Benozzo Gozzoli’s majestic fresco of the Procession of

the Magi, full of wondrous natural detail, in the Palazzo Medici – both

projects commissioned by the sickly and short-lived Piero. During

adolescence, Leonardo witnessed the execution and public installation

of several of the sculptures that Verrocchio fashioned for Lorenzo,

including the tombs for Piero and his brother Giovanni de’ Medici.

Years later, Leonardo would still recall with awe Verrocchio’s engi-

neering feat in fabricating and mounting the famous copper orb on

the lantern of the dome of Florence Cathedral in 1471. The entire

city marveled, the merchant Benedetto Dei thereafter calling the artist

“Verrocchio of the Ball” (della Palla). The versatile master’s accom-

plishment may have stimulated Leonardo’s own engineering interests;

several of the young man’s drawings from that period either record or

were inspired by the hoist and crane used to install the Duomo sphere.

Not only would Leonardo have admired the technological equipment;

but also, as one who dreamed of human flight, he must have enviously

imagined the view from atop that soaring perch, by far the highest

point in the city.

3. The Cultural Climate of Florence 19

Figure 2.

Filippo Lippi, Adoration

of the Christ Child,

c. 1459, oil on panel,

formerly at the chapel

in the Medici Palace,

now in Berlin, Staatliche

Museen Preussischer

Kulturbesitz,

Gem

¨

aldegalerie.

Erich Lessing/Art

Resource, NY.

Leonardo also saw the ascent, under Piero and Lorenzo, of the

major painters Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Antonio

and Piero Pollaiuolo, and Luca Signorelli. Piero ordered or purchased

important works by several of these innovative artists, among them

three large paintings by Antonio Pollaiuolo of the mythological Labors

of Hercules for the Medici palace on the via Larga (lost but known

through small, autograph replicas). Whereas the perpetually ill and

eczema-ridden Piero felt the need to display these unsubtle symbols

of power and military prowess, his sagacious wife, Lucrezia, adher-

ing to Cosimo’s strategy of humility, kept a relatively low profile,

retaining the unpretentious “Tornabuoni” as her family name rather

than reverting to her family’s original, noble appellation, Tornaquinci.

She understood the danger of appearing too aristocratic in republican

Florence.

20 The Young Leonardo

Their son, Lorenzo, preferred writing poetry and collecting gems

and other small objets d’art to the acquisition of paintings. Nonethe-

less, he did commission portraits and an altarpiece from Botticelli, fres-

coes from Ghirlandaio, and obtained some pictures in oil by esteemed

Flemish masters. In his relatively accessible, ground-floor bedroom in

the palace hung Uccello’s paintings of the mythological Judgment of

Paris and a scene of lions fighting dragons (these were joined, in 1484,

by Uccello’s famous tri-paneled Battle of San Romano). The precocious

Leonardo would have especially enjoyed the lion-and-dragon combat

when he was permitted to examine these paintings from time to time.

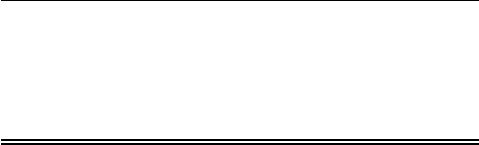

During his early apprenticeship with Verrocchio, Leonardo drew the

snarling heads of a lion and a dragon in confrontation – beasts for

which he seems to have had an enduring fondness (fig. 3). (Report-

edly, much later, for French king Francis I, he made a grand image of

a dragon fighting a lion, distorted in extreme perspective, or anamor-

phosis.) By the later 1470s, the young artist managed to gain entrance

into Lorenzo’s famed garden beside San Marco, where Lorenzo kept

part of his sculpture collection and allowed a lucky few to study and

work.

Despite this privilege, there is no evidence to suggest that Leonardo

was admitted into the meetings of the “Platonic Academy,” the name

an informal group of intellectuals at the Medici court invented for

themselves in the 1460s. The “academicians,” who often gathered at

Lorenzo’s refurbished villa at Carreggi, included Ficino, the famous

Greek scholar Johannes Argyropouos, whom Cosimo had brought to

Florence, the erudite young poets Angelo Poliziano and Cristoforo

Landino (a commentator on the works of Virgil, Horace, and Dante),

and the architect, art theorist, and writer Leon Battista Alberti, who

gloried in the role of venerable counselor and was, until his death in

1472, probably Leonardo’s most direct connection to the group. The

Neoplatonists, as they came to be called, discussed not only arcane

subjects, such as Plato’s views on the immortality of the soul and the

nature of God, but also the relative merits of the active life versus

the contemplative life and what personal qualities or accomplishments

determined “nobility.”

Although these issues were not central or pressing for Leonardo,

whose investigations were more pragmatic and Aristotelian, concern-

ing the observable, natural world, his exclusion from the academy’s

conversations may account for the anger he occasionally expressed.

3. The Cultural Climate of Florence 21

Figure 3.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Study of the Virgin

Nursing with St. John the

Baptist, Figure and Head

Studies, Heads of a Lion

and Dragon,c.1480,

pen and ink, Windsor

Castle, Royal Library

(12276r). The Royal

Collection

C

2010

Her Majesty Queen

Elizabeth II.

(Ficino sometimes referred to intellectuals who, like Leonardo,

were not proficient in the classical languages, as levissimi, Latin for

“lightweights.”) Notwithstanding his lack of scholarly credentials,

Leonardo was probably permitted, once in a while, to attend lec-

tures given by Alberti, Argyropoulos (an authority on Aristotle’s

writings), and other members. Lorenzo seems occasionally to have

made the Medici library available to the artist. This contained at least

six works of Aristotle and some scientific and medical tracts, such

as Cornelius Celsus’ first-century On Medicine (De medicina), Pliny

the Elder’s first-century Natural History, Theophrastus’ On Botany

22 The Young Leonardo

(third century b.c.) and Flavius Vegetius Renatus’ fourth-century vet-

erinary manual De mulomedicina, along with many volumes of poetry

and historical and religious texts.

Meanwhile, Leonardo’s father performed well enough as a notary

to attain, by 1469, a job at the Palazzo del Podest

`

a (the present-day

Bargello), the seat of the highest law officer and main criminal court

in Florence. In the next year, he moved to the via delle Prestanze

(later called the via dei Gondi), in the neighborhood of the Palazzo

della Signoria, the city hall, into what would have been an upscale

house with airy rooms appointed, in the Florentine manner, with

small assemblies of painted furniture, set against mainly bare walls.

The relative austerity of the interior d

´

ecor reflected the frugal way in

which the typical Florentine household was run.

The forty-three-year-old Ser Piero brought to the new casa asec-

ond wife, Francesca di Ser Giuliano Lanfredi, and hopes for many chil-

dren. Unfortunately, his wishes were delayed. His first legitimate heir,

Antonio, arrived seven years later, born to his third wife, Margherita,

in 1476. He quickly went on to have another son with Margherita,

however, and seven more sons and two daughters with a fourth spouse,

Lucrezia. Because of the Renaissance’s high mortality rate of women

in childbirth, it was not unusual for a man to marry a few times

and to change residences, as his family evolved and grew. Leonardo,

by far the oldest of Ser Piero’s brood (by almost twenty-four years),

would have lived, as was customary for workshop assistants, mainly at

Verrocchio’s house and shop in the via dell’Agnolo, near the church of

S. Ambrogio. We know nothing of Leonardo’s relationships with his

stepmothers in Florence, but one of Leonardo’s biological analogies

may offer a clue. Observing how trees give abundant sap to grafted

limbs, the artist asserted that fathers and mothers “bestow much more

attention upon their stepchildren than upon their own children.”

Ser Piero’s elevated status and the many important connections

he made in his new position – with Verrocchio, the sculptor Andrea

della Robbia, and other artists and potential patrons – may have helped

solidify Leonardo’s place in Verrocchio’s workshop and sometime later,

by 1472, secure his membership in the painters’ confraternity or pro-

fessional club, the Compagnia di S. Luca (Company of Saint Luke).

Through his contacts and clients, Ser Piero seems to have worked

continuously to advance Leonardo’s career. No record has been

found, however, to indicate that the artist’s father ever took steps to

3. The Cultural Climate of Florence 23

“legitimate” him, a legal process involving the approval of Florence’s

governing councils. This would have made Leonardo eligible to

inherit property and, more important, would have removed some

of the stain of dishonor. This is a curious fact, given Ser Piero’s pro-

fession and status and – what must have been a great and growing

concern – his failure, during twenty-three years of marriage, to pro-

duce a legitimate heir.

4. First Years in Florence and

the Verrocchio Workshop

D

espite a certain confidence born of his many gifts,

the newly arrived, adolescent Leonardo must have found

the urban congestion of Florence and the desperate squalor of so

many who lived there a bit intimidating. From the airy public squares

spanned countless, winding streets and blind passages, many made

almost impassible by vendors’ stalls and filthy shacks. As in most

European cities, the poor, rural

´

emigr

´

es, and itinerant workers – alto-

gether, roughly half of Florence’s population – mainly hunkered down

in makeshift housing, crude wooden structures and lean-tos, braced

against churches and other masonry buildings.

Agricultural life was then much more intrusive and obtrusive than

it is today. Horses, donkeys, cattle, and other livestock were every-

where led through the narrow streets. Piles of hay and manure were

ubiquitous. Carts and mule trains, loaded with wool, raw silk, leather,

and produce, angled their way past these obstacles and large open-pit

quarries of pietra forte, the stone from which most of the palaces and

houses were built. Animal parts that could not be used by butchers or

leather makers were freely discarded in the streets, usually at the spots

where the livestock had been slaughtered. Carcasses floated in the

Arno as well, along with massive debris and chemical residues gener-

ated by the wool workers and dyers, who labored under lofty wooden

sheds (tiratoi) and pavilions along the river. A perpetual source of flood

and the city’s main sewer, the Arno was considered by most to be,

in Dante’s words, a “cursed and unlucky ditch” (Purgatory,XIV,51).

In January 1465, probably just a year or so after Leonardo’s arrival in

Florence, the river flooded all the way to the Canto a Monteloro (now

the corner of via degli Alfani and Borgo Pinti), causing lay benches

to float there from the church of Santa Croce, and filling the ground

25

26 The Young Leonardo

floors of the Podest

`

a (later, Ser Piero’s workplace) and nearby apothe-

caries with water and waste. Needless to say, rodents were always a

problem, as was disease, which the populace attributed to the putrid

smells of the city rather than to the true source, rat-borne fleas. After

the Black Death had wiped out half of the Florentine citizenry in

the mid-fourteenth century, plagues came cyclically, nearly every few

years, throughout the fifteenth.

Fortunately, nature also intruded into the city in more benevolent

ways. Many people owned fine horses and kept hounds, songbirds, and

other pets. Some of the more affluent had gardens, with flowers both

native and imported from afar, such as exotic varieties of jasmine. Most

convents and monasteries maintained their own private gardens and

small orchards. At that time, there were also many small, unpaved, and

untended open spaces, where grasses and shrubs grew wildly and trees

provided shelter and shade. These were not parks in the modern sense,

but neglected places that offered respite or, in the case of one lightly

wooded, if ragged, tract of land near the church of SS. Annunziata,

opportunity for sketching. Not far from the city’s center, on the part

of the Arno far to the east of the Ponte Vecchio (upstream from

the wool industry), waterbirds thrived and fisherman armed with

poles and huge nets hauled in bounties of carp, cod, and trout. On

the outskirts of Florence, there were pastures and the lush, flowery

meadows from which the city had derived its name. Thus, Leonardo

found in and around the city at least some semblance of his former

life and surroundings.

When, perhaps in 1465 or 1466, he entered Verrocchio’s large

bottega or shop, which produced marble and bronze sculptures as well

as paintings and frames, it had an extensive crew and well-established,

if alternating, divisions of labor. Of an inherently sensitive nature,

Leonardo was probably initially overwhelmed by the din of stone-

chipping and metal-clanging and by the visible air, choked with marble

dust, sulphur, and the pungent odor of spilt wine. At that time, he

may have seen some craftsmen on their knees polishing the large

bell, years later affectionately called La Piagnona, the “great weeping

lady.” The bell was so-named because it summoned to the church of

San Marco the piagnoni, the “weeping” followers of the controversial

Dominican friar, Girolamo Savonarola, burned at the stake for heresy

in 1498. Leonardo possibly observed in another part of the studio