Feinberg L.J. The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4. First Years in Florence and the Verrocchio Workshop 27

Verrocchio himself, adding the finishing touches to his marble bust of

the Florentine patrician Francesco Sassetti (c. 1464–65). The master,

undoubtedly, would have taken him across town to see the holy-water

basin (lavamano) that he, when an assistant, had years earlier created

with the sculptor Antonio Rossellino for the Old Sacristy of San

Lorenzo.

Unusually versatile, Verrocchio was one of the few sculptors of

his time to work in both bronze and marble and one of the rare

sculptors who also painted. The contemporary Florentine writer and

civic booster Ugolino Verino praised Verrocchio as comparable to the

ancient sculptor Phidias, noting that he even “surpasses the Greek in

one respect, for he both casts and paints.” In fifteenth-century Flo-

rence, only Verrocchio, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Antonio Pollaiuolo

combined those skills. Verrocchio was reportedly a competent musi-

cian as well.

Although born (between 1434 and 1437) to an artisan family that

was not especially wealthy, Verrocchio was very literate and cultured,

with a small library of classical and humanist texts, including the

first-century Heroides of Ovid and the fourteenth-century Triumphs of

Petrarch. He devoted himself to the study of antique art. He probably

knew more about ancient Greek and Roman sculpture than anyone

of his generation. Although such pieces informed his works, he rarely

chose – or was given the opportunity – to tackle classical subject

matter in his art. Nonetheless, his knowledge and talents profoundly

impressed the Medici, who gave him as many commissions as he could

handle; his earliest surviving sculptures, the lavamano and La Piagnona,

were created for Medici churches, and Sassetti, of whom he carved an

arresting bust, was the Medici’s banker.

After Verrocchio completed those works, the family assigned him

a range of projects in various media – a bronze sculpture of David

(c. 1465), the marble and porphyry tombs for Cosimo, Piero, and

Giovanni de’ Medici (c. 1465–67 and c. 1469–73), a polychromed

terracotta relief of the Resurrection (c. 1470) and a bronze Putto with

Dolphin (c. 1470–early 1480s) for the Medici villa at Careggi, and

an altarpiece, depicting the Virgin and Child with saints, for the

cathedral in Pistoia (c. 1475). Always accommodating, Verrocchio and

his assistants also produced painted-canvas standards for Medici jousts

(1469 and 1475) and elaborate festival decorations for the state visit of

28 The Young Leonardo

the Duke of Milan in 1471. Through him, Leonardo gained a useful

understanding of the Medici’s tastes and interests.

Apparently, however, Verrocchio never mastered the fresco tech-

nique and so was not able to teach it to Leonardo and other shop

assistants. This partly explains why Leonardo chose unconventional

means when he was later assigned to create large murals, such as his

Last Supper for the Milanese church of S. Maria delle Grazie and Battle

of Anghiari for the Florentine Palazzo della Signoria. In both cases,

he employed highly experimental media and consequently watched

his works begin to decay almost as soon as he laid them on the wall.

As we shall see, Leonardo probably lacked the desire and patience to

learn the laborious fresco technique from skilled practitioners in other

ateliers.

He seems also to have inherited certain unfortunate work habits

from Verrocchio’s shop, specifically the tendency, shared by modern

building contractors, to move on to a new project before completing

the one at hand. Two major paintings produced by the shop (on which

Leonardo collaborated), the Pistoia Madonna della Piazza (fig. 21)and

the Baptism of Christ (fig. 22), were both completed years after they

were begun, with long periods during which the works were left to

gather dust. Later, the famous sixteenth-century biographer of artists,

Giorgio Vasari, lamented Verrocchio’s inability to finish pictures, a

failing that he would retain until the end of his life, as evidenced by

the incomplete quadro grande (large picture) and other works listed in

his estate.

Normally, a young man apprenticed to an artist spent his days

grinding colors, preparing gesso, and fulfilling numerous other duties

until the master deemed him worthy to participate in the actual exe-

cution of works. Given the varied activities of Verrocchio’s enterprise

and Leonardo’s great capacity to learn, his novitiate would have

involved an increasingly – and unusually – wide range of experiences,

perhaps as much in the applied and technical arts of casting bronze

and hoisting blocks of stone as in the fine art of draftsmanship. Highly

stimulated by the bustle and exchange of professional secrets, Leonardo

nevertheless would have spent many tedious hours employed in the

lowly tasks of the creato (literally, “creature,” as such assistants were

called) before his master, Verrocchio, assured of his abilities with pen

and brush, allowed him to assist on paintings.

4. First Years in Florence and the Verrocchio Workshop 29

Leonardo would have received a bare subsistence wage, probably

supplemented with funds from Ser Piero, who initially paid for his

son’s internship with the master. The young man’s starting annual

salary might have been as low as 6 or 8 florins and would have risen,

by the time he was seventeen (the earliest age at which assistants

became independent masters), to perhaps 18 or 20 florins. We know

that a shop assistant to the contemporary Florentine painter Neri di

Bicci received the annual sum of 15 florins, along with “a pair of

hose.” The pay of the creato was even less than it seems on face, for

an illiterate, low-level servant would have been paid perhaps 8 florins

per year, an unskilled laborer could have expected to receive 30 to 40

florins, a druggist 50, a civil servant 70, and a senior municipal official

as much as 300 florins annually. Moreover, a workshop member was,

like a servant, at the master’s constant beck and call, obliged to be

available for work at all hours of the day and night and even on

holidays if necessary. To cast the situation in a somewhat happier light,

one might say that Leonardo had joined a professional “family,” in

which his life was entwined with the master’s and in which notions

of individual privacy (then as now in Italy) hardly existed.

After Leonardo had demonstrated his considerable painterly tal-

ents, he still would have been rather restricted in how he could apply

them. Understandably, products from Verrocchio’s shop were required

to follow the master’s design and style closely, despite the many con-

tributing hands. For this reason, the principal figures in paintings, even

those touched by Leonardo, adhered to strict prototypes, often gen-

erated from cartoons (full-sized preparatory drawings) that the master

produced. Assistants normally could assert their individuality in a shop

piece only in less prominent details, such as a distant landscape or other

minor, natural elements.

Tales of Leonardo’s juvenile inclinations and adventures suggest

that he was always drawn to the natural world and was, no doubt,

happy to be anointed as the one primarily responsible for the natural

elements in Verrocchio workshop pictures. In light of its specificity

of detail, there may well be some truth to the aforementioned story,

related by Giorgio Vasari, that the inventive, young Leonardo painted

on a buckler, or shield, a “monster of poisonous breath, belching – fire

from its eyes and smoke from its nostrils,” a pastiche of various parts of

lizards, insects, and other, repulsive creatures he had collected. Later,

30 The Young Leonardo

according to Vasari, Leonardo prepared for the Medici a tapestry car-

toon representing Adam and Eve in a verdant landscape with animals

and much vegetation, including accomplished depictions of a palm,

a fig tree, and “a meadow with an infinite variety of herbs.” That

composition is lost, along with a painting of the Head of Medusa,

undoubtedly a tour de force demonstration of Leonardo’s snake-

rendering skills, once kept in the Medici storage vault, the guardaroba.

Leonardo’s ingenuity and zoological knowledge would not have

escaped the attention of Verrocchio, who, as a former goldsmith,

had himself created a “cup full of [that is, decorated with] animals”

and other “bizarre fancies.”

Some reports of Leonardo’s concern for animals sometimes sound

almost like passages from a hagiography of Francis of Assisi, such as

the claim that the artist sometimes bought songbirds from their sellers

only to release them to freedom. Yet, seemingly corroborating this

story, Leonardo once wrote that “the goldfinch will carry spurge [a

deadly poison] to its little ones imprisoned in a cage – death rather

than loss of liberty.” It is known that, later in life, Leonardo kept

many horses. (This was an unusual luxury in that most artists could

only afford to rent horses or to own mules.) He apparently also loved

dogs. Every now and then, he would pause from his work to sketch a

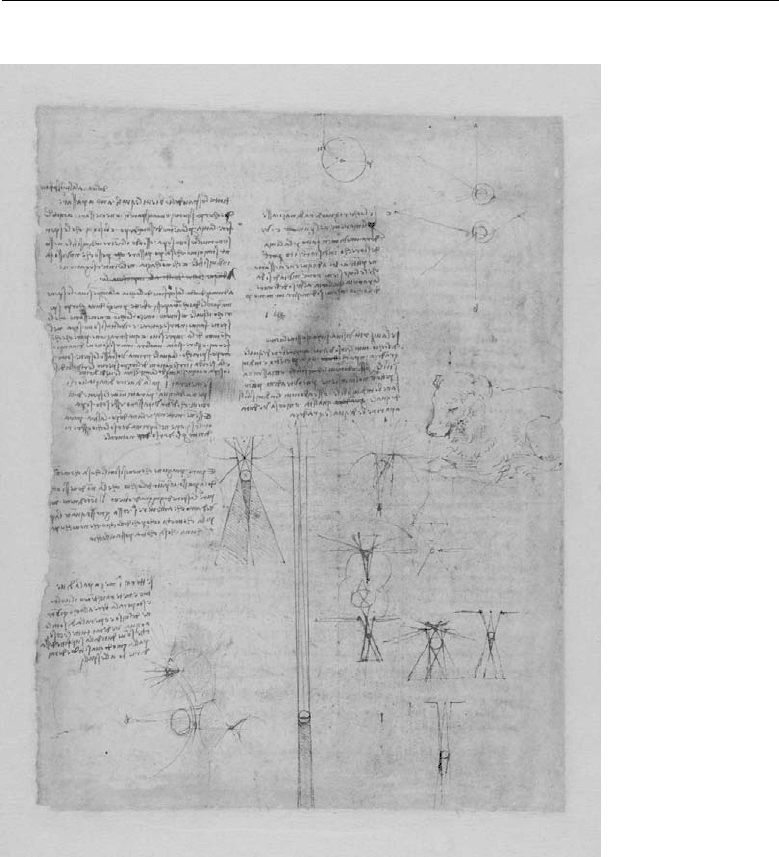

canine companion in the margin of the page before him. On a sheet

of Leonardo’s optical illustrations in the manuscript known as the

“Codice Atlantico” (in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan), there is

one such study of a dog, evidently content simply to sit quietly beside

its inattentive master, the animal well accustomed to his interminable

periods of drawing and writing (fig. 4). The hound may have been

the lone, welcome guest in his studio; he advised artists to work in

solitude, allowing the presence of colleagues only if absolutely neces-

sary. Throughout his life, Leonardo conducted research in comparative

anatomy and drew a wide range of animals, both real and imaginary;

the only, unfortunate, omission from his pictorial bestiary, because of

his absence from Florence, was the beloved, doomed giraffe, given to

Lorenzo de’ Medici as a gift by the sultan of Egypt in 1487,which

died after striking its head on a beam in the Medici palace.

In fact, the artist’s fascination with nature intersected with that of

Lorenzo, one of several interests that the two young men shared,

which may have formed the basis for a respectful and cordial

4. First Years in Florence and the Verrocchio Workshop 31

Figure 4.

Leonardo da Vinci,

Optical Studies and

Resting Dog,c.1492–

95?, pen and ink, Milan,

Biblioteca Ambrosiana,

Codice Atlantico (599r).

Finsiel/Alinari/Art

Resource, NY.

relationship. Lorenzo, who assembled a famed menagerie, enthusi-

astically bred fine horses (for which Leonardo designed stables), cattle,

pigs, hounds, and rabbits. His poetry, mainly pastoral, teemed with

animal and landscape imagery: cranes and falcons, deer and oxen, ilex

trees and olive groves, and rushing streams. Just three years Leonardo’s

senior, the high-spirited Lorenzo also would have appreciated the

artist’s musical abilities and irreverent sense of humor, about which I

will later comment at length. Il Magnifico composed and sang hunt-

ing and love songs and was notorious for telling funny, often ribald,

32 The Young Leonardo

stories. His carpe diem attitude is revealed in the jaunty, carnival song

he wrote in 1470:

How lovely is youth –

Yet it slips away;

If you can be happy, be so.

For there is no certainty about tomorrow.

Some allowances should be made for the clich

´

es, refrained in subse-

quent verses; the lyricist was barely out of his teens.

5. First Works in Florence

and the Artistic Milieu

T

he earliest surviving traces of Leonardo’s hand – and

affection for animals – would seem to be found in the Tobias

and the Angel (c. 1472–73), now in the National Gallery, London

(fig. 5), a collaborative picture from the Verrocchio shop. The partic-

ipation of two hands in the work’s execution has long been apparent,

in light of the stylistic contrast between the sculptural rigidity of the

anatomy and costumes of the figures and the more freely rendered

dog and fish. The wavelike patterns of the dog’s unruly fur compare

closely to the many sketches of the movement of water and hair that

soon after streamed from Leonardo’s pen. The dead-eyed helplessness

and glistening scales of the carp (or tinca), gasping for breath, sug-

gest the touch of someone who studied aquatic life closely. Famously

able to survive for long periods out of water, the common river fish

would have provided a live (and fresh-smelling) model for hours before

becoming a meal.

An appreciative Verrocchio may have permitted Leonardo’s brush

to delineate as well the lively, luminescent curls of Tobias’s hair and

the intricate, knotted and fluttering belts and hems of the figures’

garments. Leonardo no doubt distinguished himself in the studio in

such subtle application of highlights and in the other remarkable effects

of illumination he could attain in the mixed media of tempera and oil

paint, then relatively new to Florence. Consequently, he became the

person called on to add those last, gilt-edged details, the final polish,

before the works left the shop.

The novel medium of oil paint, which Botticelli and others were

also beginning to employ, would have much intrigued Leonardo. With

it he knew that he could achieve qualities of translucency and trans-

parency that far surpassed the capabilities of tempera and fresco as well

33

34 The Young Leonardo

as tenors of expression that the literal-minded Flemish, originators of

the technique, had just barely explored. He had found a vehicle not

only for success but also for investigation; his experimentation with

media would continue for more than thirty years, with either sublime

or disastrous results.

A respectful homage to a painting of the same theme by the broth-

ers Antonio and Piero Pollaiuolo, the Verrocchio-workshop Tobias

and the Angel was meant, nevertheless, to eclipse it. From the time

of the major competition for the Baptistery doors project at the

dawn of the fifteenth century, artistic rivalries were enthusiastically

encouraged and pursued in Florence. Confident in the skills of his

gifted student, Verrocchio must have felt he could compete well with

the Pollaiuolo brothers and would have welcomed the opportunity

to make a reduced variant of their painting, then on display in the

church of Orsanmichele. The commission probably came to Verroc-

chio from someone with cataracts or other eye troubles (or who had

a family member with poor vision), because the subject of the pic-

ture, from the apocryphal Book of Tobit, recalls how the young Tobit,

guided by an angel, cured his father’s blindness with the entrails of a

fish. This charming, popular story of filial piety was appended to the

Old Testament in many, early vernacular Bibles. As we shall see, the

vision-related theme would have much appealed to Leonardo, and

the implicit, painterly competition would have begun to prepare him

for a far more public and overt guerra (or war), as such artistic contests

were called, some three decades later, when he would compete with

Michelangelo in the grand salon of the city hall.

For a young artist in the Verrocchio crew, who may have felt that

he was devoting an inordinate amount of time to making studies for

pictorial gowns and dresses (a particular strength and specialty of the

shop), the works of the Pollaiuolo brothers, masters of the nude figure

in action, must have seemed exciting. Celebrated for their deliberately

ungraceful, painted and bronze figures of Hercules and other sinewy

nudes in violent engagement, the Pollaiuolo boys offered a macho,

avant-garde alternative to the conservative, luxury-goods industry of

Verrocchio. They had a well-earned reputation for artistic boldness.

Not since antiquity had classical subjects, the Labors of Hercules, been

treated on such a colossal scale – one much grander than most religious

pictures of the period. The Pollaiuoli’s large trio of canvasses in the

Medici Palace, with their stunning male nudes, must have had a public

5. First Works in Florence and the Artistic Milieu 35

Figure 5.

Workshop of Andrea del

Verrocchio (including

Leonardo da Vinci),

Tobias and the Angel,

c. 1472–73, oil on panel,

London, National

Gallery.

C

National

Gallery, London/Art

Resource, NY.

impact akin to that of the 1819 Paris unveiling of Theodore Gericault’s

painting the Raft of the Medusa, in which a sensational, contemporary

event was rendered on a monumental scale previously reserved for

high-minded, history paintings.

Leonardo furtively cast an eye on the Pollaiuoli’s heroic productions

throughout his first period in Florence and, on occasion, discreetly

borrowed from “the competition” for some of his major compositions.

The workshop of the brothers Pollaiuolo (so nicknamed because their

father was a poultry seller) was centrally located on via Vacchereccia,

opposite the Palazzo della Signoria, and therefore a convenient stop

for Leonardo, whose father lived nearby, and for other curious artists

from Verrocchio’s shop. Probably in direct response to the famous

36 The Young Leonardo

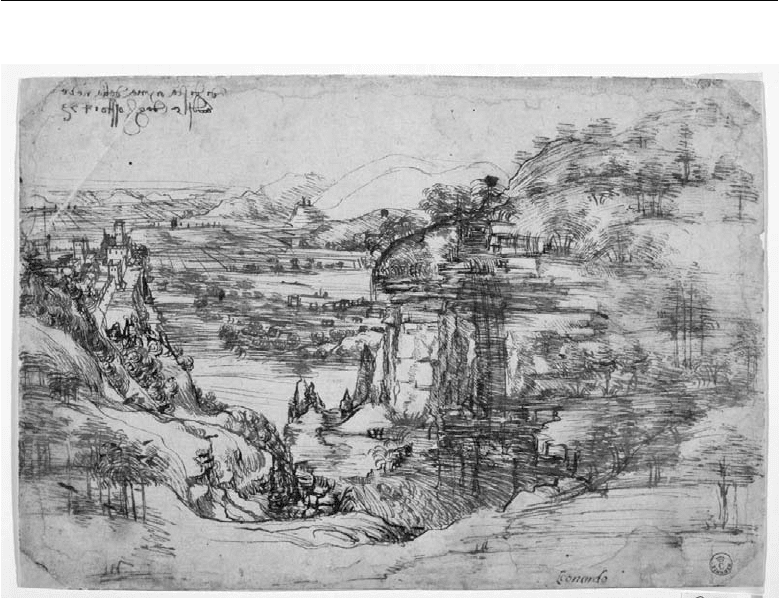

Figure 6.

Leonardo da Vinci,

View of the Arno

Valley, 1473,penand

ink, Florence, Uffizi,

Gabinetto Disegni e

Stampe. Scala/Ministero

per i Beni e le Attivit

`

a

culturali/Art Resource,

NY.

engraving of a Battle of Nudes (c. 1471–73) by his rivals, Verrocchio

created his own ostentatious, “display” drawing of the subject, long

lost. However, he never managed, in most minds, to pose a serious

challenge to Pollaiuolo preeminence in the mastery of the unclothed

male figure.

Possibly in the same year that he assisted with the Tobias, Leonardo

rendered his earliest known, dated drawing – not surprisingly, a land-

scape – presumably made on the spot (fig. 6). The vibrant sketch

captures, with familiarity, a view of the Arno River valley with the

town of Montalbano, northwest of Florence near Vinci, in the left

distance. The sheet is inscribed in his usual left-handed, backward

manner, “[feast] of Holy Mary of the Snow, day of August the 5th,

1473,” in reference to the anniversary of a miraculous snowfall, and

to a shrine in the area that commemorated it. His pen enlivens as it

records, evoking not only a spectacular, somewhat exaggerated topog-

raphy of breathtaking chasms and infinite plains but also the natural

forces of wind, heat, and geological erosion. It is clear that Leonardo,

still in his early twenties, had already spent considerable time contem-

plating the processes of geological formation and the cycling of water.