Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

INTRODUCTION

Welcome to the third edition of the Gale Environmental

Encyclopedia! Those of us involved in writing and production

of this book hope you will find the material here interesting

and useful. As you might imagine, choosing what to include

and what to exclude from this collection has been challeng-

ing. Almost everything has some environmental significance,

so our task has been to select a limited number of topics

we think are of greatest importance in understanding our

environment and our relation to it. Undoubtedly, we have

neglected some topics that interest you and included some

you may consider irrelevant, but we hope that overall you

will find this new edition helpful and worthwhile.

The word environment is derived from the French

environ, which means to “encircle” or “surround.” Thus, our

environment can be defined as the physical, chemical, and

biological world that envelops us, as well as the complex

of social and cultural conditions affecting an individual or

community. This broad definition includes both the natural

world and the “built” or technological environment, as well

as the cultural and social contexts that shape human lives.

You will see that we have used this comprehensive meaning

in choosing the articles and definitions contained in this

volume.

Among some central concerns of environmental science

are:

O

how did the natural world on which we depend come to

be as it is, and how does it work?

O

what have we done and what are we now doing to our

environment—both for good and ill?

O

what can we do to ensure a sustainable future for ourselves,

future generations, and the other species of organisms on

which—although we may not be aware of it—our lives

depend?

The articles in this volume attempt to answer those

questions from a variety of different perspectives.

Historically, environmentalism is rooted in natural his-

tory, a search for beauty and meaning in nature. Modern

environmental science expands this concern, drawing on

xxix

almost every area of human knowledge including social sci-

ences, humanities, and the physical sciences. Its strongest

roots, however, are in ecology, the study of interrelationships

among and between organisms and their physical or nonliv-

ing environment. A particular strength of the ecological

approach is that it studies systems holistically; that is, it

looks at interconnections that make the whole greater than

the mere sum of its parts. You will find many of those

interconnections reflected in this book. Although the entries

are presented individually so that you can find topics easily,

you will notice that many refer to other topics that, in turn,

can lead you on through the book if you have time to follow

their trail. This series of linkages reflects the multilevel asso-

ciations in environmental issues.

As our world becomes increasingly interrelated eco-

nomically, socially, and technologically, we find evermore

evidence that our global environment is also highly intercon-

nected. In 2002, the world population reached about 6.2

billion people, more than triple what it had been a century

earlier. Although the rate of population growth is slowing—

having dropped from 2.0% per year in 1970 to 1.2% in

2002—we are still adding about 200,000 people per day, or

about 75 million per year. Demographers predict that the

world population will reach 8 or 9 billion before stabilizing

sometime around the middle of this century. Whether natu-

ral resources can support so many humans is a question of

great concern.

In preparation for the third global summit in South

Africa, the United Nations released several reports in 2002

outlining the current state of our environment. Perhaps the

greatest environmental concern as we move into the twenty-

first century is the growing evidence that human activities

are causing global climate change. Burning of fossil fuels in

power plants, vehicles, factories, and homes release carbon

dioxide into the atmosphere. Burning forests and crop resi-

dues, increasing cultivation of paddy rice, raising billions of

ruminant animals, and other human activities also add to the

rapidly growing atmospheric concentrations of heat trapping

gases in the atmosphere. Global temperatures have begun

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

INTRODUCTION

to rise, having increased by about 1°F (0.6°C) in the second

half of the twentieth century. Meteorologists predict that

over the next 50 years, the average world temperature is

likely to increase somewhere between 2.7–11°F (1.5–6.1°C).

That may not seem like a very large change, but the difference

between current average temperatures and the last ice age,

when glaciers covered much of North America, was only

about 10°F (5°C).

Abundant evidence is already available that our cli-

mate is changing. The twentieth century was the warmest

in the last 1,000 years; the 1990s were the warmest decade,

and 2002 was the single warmest year of the past millennium.

Glaciers are disappearing on every continent. More than

half the world’s population depends on rivers fed by alpine

glaciers for their drinking water. Loss of those glaciers could

exacerbate water supply problems in areas where water is

already scarce. The United Nations estimates that 1.1 billion

people—one-sixth of the world population—now lack access

to clean water. In 25 years, about two-thirds of all humans

will live in water-stressed countries where supplies are inade-

quate to meet demand.

Spring is now occurring about a week earlier and fall

is coming about a week later over much of the northern

hemisphere. This helps some species, but is changing migra-

tion patterns and home territories for others. In 2002, early

melting of ice floes in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence appar-

ently drowned nearly all of the 200,000 to 300,000 harp seal

pups normally born there. Lack of sea ice is also preventing

polar bears from hunting seals. Environment Canada reports

that polar bears around Hudson’s Bay are losing weight and

decreasing in number because of poor hunting conditions.

In 2002, a chunk of ice about the size of Rhode Island broke

off the Larsen B ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula. As

glacial ice melts, ocean levels are rising, threatening coastal

ecosystems and cities around the world.

After global climate change, perhaps the next greatest

environmental concern for most biologists is the worldwide

loss of biological diversity. Taxonomists warn that one-

fourth of the world’s species could face extinction in the

next 30 years. Habitat destruction, pollution, introduction

of exotic species, and excessive harvesting of commercially

important species all contribute to species losses. Millions

of species—most of which have never even been named

by science, let alone examined for potential usefulness in

medicine, agriculture, science, or industry—may disappear

in the next century as a result of our actions. We know

little about the biological roles of these organisms in the

ecosystems and their loss could result in an ecological

tragedy.

Ecological economists have tried to put a price on the

goods and services provided by natural ecosystems. Although

many ecological processes aren’t traded in the market place,

xxx

we depend on the natural world to do many things for us

like purifying water, cleansing air, and detoxifying our

wastes. How much would it cost if we had to do all this

ourselves? The estimated annual value of all ecological goods

and services provided by nature are calculated to be worth

at least $33 trillion, or about twice the annual GNPs of all

national economies in the world. The most valuable ecosys-

tems in terms of biological processes are wetlands and coastal

estuaries because of their high level of biodiversity and their

central role in many biogeochemical cycles.

Already there are signs that we are exhausting our

supplies of fertile soil, clean water, energy, and biodiversity

that are essential for life. Furthermore, pollutants released

into the air and water, along with increasing amounts of

toxic and hazardous wastes created by our industrial society,

threaten to damage the ecological life support systems on

which all organisms—including humans—depend. Even

without additional population growth, we may need to dras-

tically rethink our patterns of production and disposal of

materials if we are to maintain a habitable environment for

ourselves and our descendants.

An important lesson to be learned from many environ-

mental crises is that solving one problem often creates an-

other. Chlorofluorocarbons, for instance, were once lauded

as a wonderful discovery because they replaced toxic or explo-

sive chemicals then in use as refrigerants and solvents. No

one anticipated that CFCs might damage stratospheric

ozone that protects us from dangerous ultraviolet radiation.

Similarly, the building of tall smokestacks on power plants

and smelters lessened local air pollution, but spread acid rain

over broad areas of the countryside. Because of our lack of

scientific understanding of complex systems, we are continu-

ally subjected to surprises. How to plan for “unknown un-

knowns” is an increasing challenge as our world becomes

more tightly interconnected and our ability to adjust to mis-

takes decreases.

Not all is discouraging, however, in the field of envi-

ronmental science. Although many problems beset us, there

are also encouraging signs of progress. Some dramatic suc-

cesses have occurred in wildlife restoration and habitat pro-

tection programs, for instance. The United Nations reports

that protected areas have increased five-fold over the past

30 years to nearly 5 million square miles. World forest losses

have slowed, especially in Asia, where deforestation rates

slowed from 8% in the 1980s to less than 1% in the 1990s.

Forested areas have actually increased in many developed

countries, providing wildlife habitat, removal of excess car-

bon dioxide, and sustainable yields of forest products.

In spite of dire warnings in the 1960s that growing

human populations would soon overshoot the earth’s car-

rying capacity and result in massive famines, food supplies

have more than kept up with population growth. There is

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

INTRODUCTION

more than enough food to provide a healthy diet for everyone

now living, although inequitable distribution leaves about

800 million with an inadequate diet. Improved health care,

sanitation, and nutrition have extended life expectancies

around the world from 40 years, on average, a century ago,

to 65 years now. Public health campaigns have eradicated

smallpox and nearly eliminated polio. Other terrible diseases

have emerged, however, most notably acquired immunodefi-

ciency syndrome (AIDS), which is now the fourth most

common cause of death worldwide. Forty million people

are now infected with HIV—70% percent of them in sub-

Saharan Africa—and health experts warn that unsanitary

blood donation practices and spreading drug use in Asia

may result in tens of millions more AIDS deaths in the next

few decades.

In developed countries, air and pollution have de-

creased significantly over the past 30 years. In 2002, the

Environmental Protection Agency declared that Denver—

which once was infamous as one of the most polluted cities

in the United States—is the first major city to meet all the

agency’s standards for eliminating air pollution. At about

the same time, the EPA announced that 91% of all moni-

tored river miles in the United States met the water quality

goals set in the 1985 clean water act. Pollution-sensitive

species like mayflies have returned to the upper Mississippi

River, and in Britian, salmon are being caught in the Thames

River after being absent for more than two centuries.

Conditions aren’t as good, however, in many other

countries. In most of Latin America, Africa, and Asia, less

than two % of municipal sewage is given even primary treat-

ment before being dumped into rivers, lakes, or the ocean.

In South Asia, a 2-mile (3-km) thick layer of smog covers

the entire Indian sub-continent for much of the year. This

cloud blocks sunlight and appears to be changing the climate,

bringing drought to Pakistan and Central Asia, and shifting

monsoon winds that caused disastrous floods in 2002 in

Nepal, Bangladesh, and eastern India that forced 25 million

people from their homes and killed at least 1,000 people.

Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen estimates that two million

deaths each year in India alone can be attributed to air

pollution effects.

After several decades of struggle, a world-wide ban

on the “dirty dozen” most dangerous persistent organic pol-

lutants (POPs) was ratified in 2000. Elimination of com-

pounds such as DDT, Aldrin, Dieldrin, Mirex, Toxaphene,

polychlorinated biphenyls, and dioxins has allowed recovery

of several wildlife species including bald eagles, perigrine

falcons, and brown pelicans. Still, other toxic synthetic

chemicals such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers, chro-

mated copper arsenate, perflurooctane sulfonate, and atra-

zine are now being found accumulating in food chains far

from anyplace where they have been used.

xxxi

Solutions for many of our pollution problems can be

found in either improved technology, more personal respon-

sibility, or better environmental management. The question

is often whether we have the political will to enforce pollution

control programs and whether we are willing to sacrifice

short-term convenience and affluence for long-term ecologi-

cal stability. We in the richer countries of the world have

become accustomed to a highly consumptive lifestyle. Ecolo-

gists estimate that humans either use directly, destroy, co-

opt, or alter almost 40% of terrestrial plant productivity,

with unknown consequences for the biosphere. Whether we

will be willing to leave some resources for other species and

future generations is a central question of environmental

policy.

One way to extend resources is to increase efficiency

and recycling of the items we use. Automobiles have already

been designed, for example, that get more than 100 mi/gal

(42 km/l) of diesel fuel and are completely recyclable when

they reach the end of their designed life. Although recycling

rates in the United States have increased in recent years, we

could probably double our current rate with very little sacri-

fice in economics or convenience. Renewable energy sources

such as solar or wind power are making encouraging pro-

gress. Wind already is cheaper than any other power source

except coal in many localities. Solar energy is making it

possible for many of the two billion people in the world

who don’t have access to electricity to enjoy some of the

benefits of modern technology. Worldwide, the amount of

installed wind energy capacity more than doubled between

1998 and 2002. Germany is on course to obtain 20% of its

energy from renewables by 2010. Together, wind, solar,

biomass and other forms of renewable energy have the poten-

tial to provide thousands of times as much energy as all

humans use now. There is no reason for us to continue to

depend on fossil fuels for the majority of our energy supply.

One of the widely advocated ways to reduce poverty

and make resources available to all is sustainable develop-

ment. A commonly used definition of this term is given in

Our Common Future, the report of the World Commission

on Environment and Development (generally called the

Brundtland Commission after the prime minister of Norway,

who chaired it), described sustainable development as:

“meeting the needs of the present without compromising

the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

This implies improving health, education, and equality of

opportunity, as well as ensuring political and civil rights

through jobs and programs based on sustaining the ecological

base, living on renewable resources rather than nonrenewable

ones, and living within the carrying capacity of supporting

ecological systems.

Several important ethical considerations are embedded

in environmental questions. One of these is intergenerational

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

INTRODUCTION

justice: what responsibilities do we have to leave resources

and a habitable planet for future generations? Is our profli-

gate use of fossil fuels, for example, justified by the fact that

we have technology to extract fossil fuels and enjoy their

benefits? Will human lives in the future be impoverished by

the fact that we have used up most of the easily available

oil, gas, and coal? Author and social critic Wendell Berry

suggests that our consumption of these resources constitutes

a theft of the birthright and livelihood of posterity. Philoso-

pher John Rawls advocates a “just savings principle” in which

members of each generation may consume no more than

their fair share of scarce resources.

How many generations are we obliged to plan for and

what is our “fair share?” It is possible that our use of resources

now—inefficient and wasteful as it may be—represents an

investment that will benefit future generations. The first

computers, for instance, were huge clumsy instruments that

filled rooms full of expensive vacuum tubes and consumed

inordinate amounts of electricity. Critics complained that it

was a waste of time and resources to build these enormous

machines to do a few simple calculations. And yet if this

technology had been suppressed in its infancy, the world

would be much poorer today. Now nanotechnology promises

to make machines and tools in infinitesimal sizes that use

minuscule amounts of materials and energy to carry out

valuable functions. The question remains whether future

generations will be glad that we embarked on the current

scientific and technological revolution or whether they will

wish that we had maintained a simple agrarian, Arcadian

way of life.

Another ethical consideration inherent in many envi-

ronmental issues is whether we have obligations or responsi-

bilities to other species or to Earth as a whole. An anthropo-

centric (human-centered) view holds that humans have

rightful dominion over the earth and that our interests and

well-being take precedence over all other considerations.

Many environmentalists criticize this perspective, consider-

ing it arrogant and destructive. Biocentric (life-centered)

philosophies argue that all living organisms have inherent

values and rights by virtue of mere existence, whether or not

xxxii

they are of any use to us. In this view, we have a responsibility

to leave space and resources to enable other species to survive

and to live as naturally as possible. This duty extends to

making reparations or special efforts to encourage the recov-

ery of endangered species that are threatened with extinction

due to human activities.Some environmentalists claim that

we should adopt an ecocentric (ecologically centered) out-

look that respects and values nonliving entities such as rocks,

rivers, mountains—even whole ecosystems—as well as other

living organisms. In this view, we have no right to break up

a rock, dam a free-flowing river, or reshape a landscape

simply because it benefits us. More importantly, we should

conserve and maintain the major ecological processes that

sustain life and make our world habitable.

Others argue that our existing institutions and under-

standings, while they may need improvement and reform,

have provided us with many advantages and amenities. Our

lives are considerably better in many ways than those of our

ancient ancestors, whose lives were, in the words of British

philosopher Thomas Hobbes: “nasty, brutish, and short.”

Although science and technology have introduced many

problems, they also have provided answers and possible alter-

natives as well.

It may be that we are at a major turning point in

human history. Current generations are in a unique position

to address the environmental issues described in this encyclo-

pedia. For the first time, we now have the resources, motiva-

tion, and knowledge to protect our environment and to build

a sustainable future for ourselves and our children. Until

recently, we didn’t have these opportunities, or there was

not enough clear evidence to inspire people to change their

behavior and invest in environmental protection; now the

need is obvious to nearly everyone. Unfortunately, this also

may be the last opportunity to act before our problems

become irreversible.

We hope that an interest in preserving and protecting

our common environment is one reason that you are reading

this encyclopedia and that you will find information here to

help you in that quest.

[William P. Cunningham, Managing Editor]

A

Edward Paul Abbey (1927 – 1989)

American environmentalist and writer

Novelist, essayist, white-water rafter, and self-described “de-

sert rat,” Abbey wrote of the wonders and beauty of the

American West that was fast disappearing in the name of

“development” and “progress.” Often angry, frequently

funny, and sometimes lyrical, Abbey recreated for his readers

a region that was unique in the world. The American West

was perhaps the last place where solitary selves could discover

and reflect on their connections with wild things and with

their fellow human beings.

Abbey was born in Home, Pennsylvania, in 1927. He

received his B.A. from the University of New Mexico in

1951. After earning his master’s degree in 1956, he joined

the

National Park Service

, where he served as park ranger

and fire fighter. He later taught writing at the University of

Arizona.

Abbey’s books and essays, such as Desert Solitaire

(1968) and Down the River (1982), had their angrier fictional

counterparts—most notably, The Monkey Wrench Gang

(1975) and Hayduke Lives! (1990)—in which he gave voice

to his outrage over the destruction of deserts and rivers by

dam-builders and developers of all sorts. In The Monkey

Wrench Gang Abbey weaves a tale of three “ecoteurs” who

defend the wild west by destroying the means and machines

of development—dams, bulldozers,

logging

trucks—which

would otherwise reduce forests to lumber and raging rivers

to

irrigation

channels.

This aspect of Abbey’s work inspired some radical

environmentalists, including

Dave Foreman

and other

members of

Earth First!

, to practice “monkey-wrenching”

or “ecotage” to slow or stop such environmentally destructive

practices as

strip mining

, the

clear-cutting

of old-growth

forests on

public land

, and the damming of wild rivers for

flood control, hydroelectric power, and what Abbey termed

“industrial tourism.” Although Abbey’s description and de-

fense of such tactics has been widely condemned by many

mainstream environmental groups, he remains a revered fig-

1

ure among many who believe that gradualist tactics have not

succeeded in slowing, much less stopping, the destruction

of North American

wilderness

. Abbey is unique among

environmental writers in having an oceangoing ship named

after him. One of the vessels in the fleet of the militant

Sea

Shepherd Conservation Society

, the Edward Abbey, rams

and disables

whaling

and drift-net fishing vessels operating

illegally in international waters. Abbey would have welcomed

the tribute and, as a white-water rafter and canoeist, would

no doubt have enjoyed the irony.

Abbey died on March 14, 1989. He is buried in a

desert

in the southwestern United States.

[Terence Ball]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Abbey, E. Desert Solitaire. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1968.

———. Down the River. Boston: Little, Brown, 1982.

———. Hayduke Lives! Boston: Little, Brown, 1990.

———. The Monkey Wrench Gang. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1975.

Berry, W. “A Few Words in Favor of Edward Abbey.” In What Are People

For? San Francisco: North Point Press, 1991.

Bowden, C. “Goodbye, Old Desert Rat.” In The Sonoran Desert. New York:

Abrams, 1992.

Manes, C. Green Rage: Radical Environmentalism and the Unmaking of

Civilization. Boston: Little, Brown, 1990.

Absorption

Absorption, or more generally “sorption,” is the process by

which one material (the sorbent) takes up and retains another

(the sorbate) to form a homogenous concentration at equi-

librium.

The general term is “sorption,” which is defined as

adhesion of gas molecules, dissolved substances, or liquids

to the surface of solids with which they are in contact. In

soils, three types of mechanisms, often working together,

constitute

sorption

. They can be grouped into physical sorp-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Acclimation

tion, chemiosorption, and penetration into the solid mineral

phase. Physical sorption (also known as

adsorption

) in-

volves the attachment of the sorbent and sorbate through

weak atomic and molecular forces. Chemiosorption involves

chemical bonds similar to holding atoms in a molecule.

Electrostatic forces operate to bond minerals via

ion ex-

change

, such as the replacement of sodium, magnesium,

potassium, and

aluminum

cations (+) as exchangeable bases

with

acid

(-) soils. While cation (positive

ion

) exchange is

the dominant exchange process occurring in soils, some soils

have the ability to retain anions (negative ions) such as

nitrates

,

chlorine

and, to a larger extent, oxides of sulfur.

Absorption and Wastewater Treatment

In on-site

wastewater

treatment, the

soil

absorption

field is the land area where the wastewater from the

septic

tank

is spread into the soil. One of the most common types

of soil absorption field has porous plastic pipe extending

away from the distribution box in a series of two or more

parallel trenches, usually 1.5–2 ft (30.5–61 cm) wide. In

conventional, below-ground systems, the trenches are 1.5–2

ft deep. Some absorption fields must be placed at a shallower

depth than this to compensate for some limiting soil condi-

tion, such as a hardpan or high

water table

. In some cases

they may even be placed partially or entirely in fill material

that has been brought to the lot from elsewhere.

The porous pipe that carries wastewater from the dis-

tribution box into the absorption field is surrounded by gravel

that fills the trench to within a foot or so of the ground

surface. The gravel is covered by fabric material or building

paper to prevent plugging. Another type of drainfield con-

sists of pipes that extend away from the distribution box,

not in trenches but in a single, gravel-filled bed that has

several such porous pipes in it. As with trenches, the gravel

in a bed is covered by fabric or other porous material.

Usually the wastewater flows gradually downward into

the gravel-filled trenches or bed. In some instances, such

as when the septic tank is lower than the drainfield, the

wastewater must be pumped into the drainfield. Whether

gravity flow or pumping is used, wastewater must be evenly

distributed throughout the drainfield. It is important to en-

sure that the drainfield is installed with care to keep the

porous pipe level, or at a very gradual downward slope away

from the distribution box or pump chamber, according to

specifications stipulated by public health officials. Soil be-

neath the gravel-filled trenches or bed must be

permeable

so that wastewater and air can move through it and come

in contact with each other. Good

aeration

is necessary to

ensure that the proper chemical and microbiological pro-

cesses will be occurring in the soil to cleanse the percolating

wastewater of contaminants. A well-aerated soil also ensures

slow travel and good contact between wastewater and soil.

2

How Common Are Septic Systems with Soil Absorp-

tion Systems?

According to the 1990 U.S. Census, there are about

24.7 million households in the United States that use septic

tank systems or cesspools (holes or pits for receiving sewage)

for wastewater treatment. This figure represents roughly

24% of the total households included in the census.

According to a review of local health department infor-

mation by the National Small Flows Clearinghouse, 94% of

participating health departments allow or permit the use of

septic tank and soil absorption systems. Those that do not

allow septic systems have sewer lines available to all residents.

The total volume of waste disposed of through septic systems

is more than one trillion gallons (3.8 trillion l) per year,

according to a study conducted by the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency’s Office of Technology Assessment, and

virtually all of that waste is discharged directly to the subsur-

face, which affects

groundwater

quality.

[Carol Steinfeld]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Elliott, L. F., and F. J. Stevenson, Soils for the Management of Wastes and

Waste Waters. Madison, WI: Soil Science Society of America, 1977.

O

THER

Fact Sheet SL-59, a series of the Soil and Water Science Department,

Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural

Sciences, University of Florida. February 1993.

Acaricide

see

Pesticide

Acceptable risk

see

Risk analysis

Acclimation

Acclimation is the process by which an organism adjusts to

a change in its

environment

. It generally refers to the ability

of living things to adjust to changes in

climate

, and usually

occurs in a short time of the change.

Scientists distinguish between acclimation and accli-

matization because the latter adjustment is made under natu-

ral conditions when the organism is subject to the full range

of changing environmental factors. Acclimation, however,

refers to a change in only one environmental factor under

laboratory conditions.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Acetone

In an acclimation experiment, adult

frogs

(Rana tem-

poraria) maintained in the laboratory at a temperature of

either 50°F (10°C) or 86°F (30°C) were tested in an environ-

ment of 32°F (0°C). It was found that the group maintained

at the higher temperature was inactive at freezing. The group

maintained at 50°F (10°C), however, was active at the lower

temperature; it had acclimated to the lower temperature.

Acclimation and acclimatization can have profound

effects upon behavior, inducing shifts in preferences and

in mode of life. The golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus)

prepares for hibernation when the environmental tempera-

ture drops below 59°F (15°C). Temperature preference tests

in the laboratory show that the hamsters develop a marked

preference for cold environmental temperatures during the

pre-hibernation period. Following arousal from a simulated

period of hibernation, the situation is reversed, and the ham-

sters actively prefer the warmer environments.

An acclimated microorganism is any microorganism

that is able to adapt to environmental changes such as a

change in temperature or a change in the quantity of oxygen

or other gases. Many organisms that live in environments

with seasonal changes in temperature make physiological

adjustments that permit them to continue to function nor-

mally, even though their environmental temperature goes

through a definite annual temperature cycle.

Acclimatization usually involves a number of inter-

acting physiological processes. For example, in acclimatizing

to high altitudes, the first response of human beings is to

increase their breathing rate. After about 40 hours, changes

have occurred in the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood,

which makes it more efficient in extracting oxygen at high

altitudes. As this occurs, the breathing rate returns to normal.

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Ford, M. J. The Changing Climate: Responses of the Natural Fauna and

Flora. Boston: G. Allen and Unwin, 1982.

McFarland, D., ed. The Oxford Companion to Animal Behavior. Oxford,

England: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Stress Responses in Plants: Adaptation and Acclimation Mechanisms. New

York: Wiley-Liss, 1990.

Accounting for nature

A new approach to national income accounting in which

the degradation and depletion of natural resource stocks

and environmental amenities are explicitly included in the

calculation of net national product (NNP). NNP is equal

to gross national product (GNP) minus capital depreciation,

and GNP is equal to the value of all final goods and services

3

produced in a nation in a particular year. It is recognized

that

natural resources

are economic assets that generate

income, and that just as the depreciation of buildings and

capital equipment are treated as economic costs and sub-

tracted from GNP to get NNP, depreciation of natural

capital should also be subtracted when calculating NNP. In

addition, expenditures on environmental protection, which

at present are included in GNP and NNP, are considered

defensive expenditures in accounting for

nature

which

should not be included in either GNP or NNP.

Accuracy

Accuracy is the closeness of an experimental measurement

to the “true value” (i.e., actual or specified) of a measured

quantity. A “true value” can determined by an experienced

analytical scientist who performs repeated analyses of a sam-

ple of known purity and/or concentration using reliable,

well-tested methods.

Measurement is inexact, and the magnitude of that

exactness is referred to as the error. Error is inherent in

measurement and is a result of such factors as the

precision

of the measuring tools, their proper adjustment, the method,

and competency of the analytical scientist.

Statistical methods are used to evaluate accuracy by

predicting the likelihood that a result varies from the “true

value.” The analysis of probable error is also used to examine

the suitability of methods or equipment used to obtain,

portray, and utilize an acceptable result. Highly accurate data

can be difficult to obtain and costly to produce. However,

different applications can require lower levels of accuracy

that are adequate for a particular study.

[Judith L. Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Jaisingh, Lloyd R. Statistics for the Utterly Confused. New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill Professional, 2000.

Salkind, Neil J. Statistics for People Who (Think They) Hate Statistics. Thou-

sand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc., 2000.

Acetone

Acetone (C

3

H

6

0) is a colorless liquid that is used as a solvent

in products, such as in nail polish and paint, and in the

manufacture of other

chemicals

such as

plastics

and fibers.

It is a naturally occurring compound that is found in plants

and is released during the

metabolism

of fat in the body.

It is also found in volcanic gases, and is manufactured by

the chemical industry. Acetone is also found in the

atmo-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Acid and base

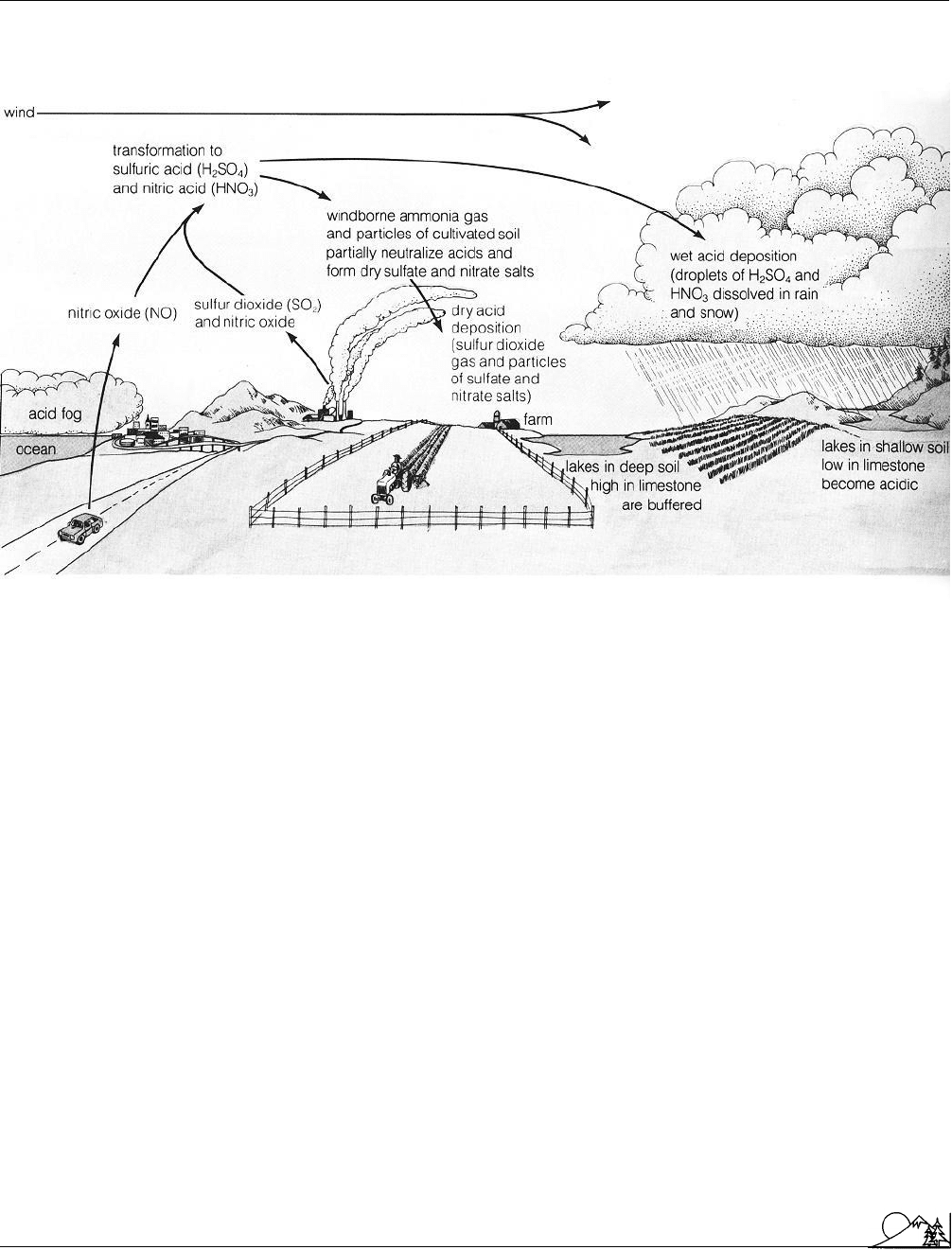

The basic mechanisms of acid deposition. (Illustration by Wadsworth Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

sphere

as an oxidation product of both natural and

anthro-

pogenic

volatile organic compounds (VOCs). It has a strong

smell and taste, and is soluble in water. The evaporation

point of acetone is quite low compared to water, and the

chemical is highly flammable. Because it is so volatile, the

acetone manufacturing process results in a large percentage

of the compound entering the atmosphere. Ingesting acetone

can cause damage to the tissues in the mouth and can lead

to unconsciousness. Breathing acetone can cause irritation

of the eyes, nose, and throat; headaches; dizziness; nausea;

unconsciousness; and possible coma and death. Women may

experience menstrual irregularity. There has been concern

about the carcinogenic nature of acetone, but laboratory

studies, and studies of humans who have been exposed to

acetone in the course of their occupational activities show

no evidence that acetone causes

cancer

.

[Marie H. Bundy]

Acid and base

According to the definition used by environmental chemists,

an acid is a substance that increases the

hydrogen ion

(H

+

)

4

concentration in a solution and a base is a substance that

removes hydrogen ions (H

+

) from a solution. In water, re-

moval of hydrogen ions results in an increase in the hydroxide

ion (OH

-

) concentration. Water with a

pH

of 7.0 is neutral,

while lower pH values are acidic and higher pH values

are basic.

Acid deposition

Acid

precipitation from the

atmosphere

, whether in the

form of dryfall (finely divided acidic salts), rain, or snow.

Naturally occurring carbonic acid normally makes rain and

snow mildly acidic (approximately 5.6

pH

). Human activities

often introduce much stronger and more damaging acids.

Sulfuric acids formed from sulfur oxides released in

coal

or

oil

combustion

or smelting of sulfide ores predominate as

the major atmospheric acid in industrialized areas. Nitric

acid created from

nitrogen oxides

, formed by oxidizing

atmospheric

nitrogen

when any fuel is burned in an oxygen-

rich

environment

, constitutes the major source of acid pre-

cipitation in such cities as Los Angeles with little industry,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Acid mine drainage

but large numbers of trucks and automobiles. The damage

caused to building materials, human health, crops, and natu-

ral ecosystems by atmospheric acids amounts to billions of

dollars per year in the United States.

Acid mine drainage

The process of mining the earth for

coal

and metal ores

has a long history of rich economic rewards—and a high

level of environmental impact to the surrounding aquatic

and terrestrial ecosystems. Acid mine

drainage

is the highly

acidic, sediment-laden

discharge

from exposed mines that

is released into the ambient aquatic

environment

. In large

areas of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Kentucky, the

bright orange seeps of acid mine drainage have almost com-

pletely eliminated aquatic life in streams and ponds that

receive the discharge. In the Appalachian coal mining region,

almost 7,500 mi (12,000 km) of streams and almost 30,000

acres (12,000 ha) of land are estimated to be seriously affected

by the discharge of uncontrolled acid mine drainage.

In the United States, coal-bearing geological strata

occur near the surface in large portions of the Appalachian

mountain region. The relative ease with which coal could

be extracted from these strata led to a type of mining known

as

strip mining

that was practiced heavily in the nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries. In this process, large amounts

of earth, called the

overburden

, were physically removed

from the surface to expose the coal-bearing layer beneath.

The coal was then extracted from the rock as quickly and

cheaply as possible. Once the bulk of the coal had been

mined, and no more could be extracted without a huge

additional cost, the sites were usually abandoned. The rem-

nants of the exhausted coal-bearing rock and

soil

are called

the

mine spoil waste

.

Acid mine drainage is not generated by strip mining

itself but by the nature of the rock where it takes place.

Three conditions are necessary to form acid mine drainage:

pyrite-bearing rock, oxygen, and iron-oxidizing bacteria. In

the Appalachians, the coal-bearing rocks usually contain

significant quantities of pyrite (iron). This compound is

normally not exposed to the

atmosphere

because it is buried

underground within the rock; it is also insoluble in water.

The iron and the sulfide are said to be in a reduced state,

i.e., the iron atom has not released all the electrons that it

is capable of releasing. When the rock is mined, the pyrite

is exposed to air. It then reacts with oxygen to form ferrous

iron and sulfate ions, both of which are highly soluble in

water. This leads to the formation of sulfuric acid and is

responsible for the acidic nature of the drainage. But the

oxidation can only occur if the bacteria Thiobacillus ferrooxi-

dans are present. These activate the iron-and-sulfur oxidizing

5

reactions, and use the energy released during the reactions

for their own growth. They must have oxygen to carry these

reactions through. Once the maximum oxidation is reached,

these bacteria can derive no more energy from the com-

pounds and all reactions stop.

The acidified water may be formed in several ways. It

may be generated by rain falling on exposed mine spoils

waste or when rain and surface water (carrying

dissolved

oxygen

) flow down and seep into rock fractures and mine

shafts, coming into contact with pyrite-bearing rock. Once

the acidified water has been formed, it leaves the mine area

as seeps or small streams.

Characteristically bright orange to rusty red in color

due to the iron, the liquid may be at a pH of 2–4. These

are extremely low pH values and signify a very high degree

of acidity. Vinegar, for example, has a pH of about 4.7 and

the pH associated with

acid rain

is in the range of 4–6.

Thus, acid mine drainage with a pH of 2 is more acidic

than almost any other naturally occurring liquid release in

the environment (with the exception of some volcanic lakes

that are pure acid). Usually, the drainage is also very high

in dissolved iron, manganese,

aluminum

, and suspended

solids.

The acidic drainage released from the mine

spoil

wastes usually follows the natural

topography

of its area

and flows into the nearest streams or

wetlands

where its

effect on the

water quality

and

biotic community

is unmis-

takable. The iron coats the stream bed and its vegetation as a

thick orange coating that prevents sunlight from penetrating

leaves and plant surfaces.

Photosynthesis

stops and the

vegetation (both vascular plants and algae) dies. The acid

drainage eventually also makes the receiving water acid. As

the pH drops, the fish, the invertebrates, and algae die when

their

metabolism

can no longer adapt. Eventually, there is

no life left in the stream with the possible exception of

some bacteria that may be able to tolerate these conditions.

Depending on the number and volume of seeps entering a

stream and the volume of the stream itself, the area of

impact may be limited and improved conditions may exist

downstream, as the acid drainage is diluted. Abandoned

mine spoil areas also tend to remain barren, even after de-

cades. The colonization of the acidic mineral soil by plant

species

is a slow and difficult process, with a few

lichens

and aspens being the most hardy species to establish.

While many methods have been tried to control or

mitigate the effects of acid mine drainage, very few have

been successful. Federal mining regulations (

Surface Min-

ing Control and Reclamation Act

of 1978) now require

that when mining activity ceases, the mine spoil waste should

be buried and covered with the overburden and vegetated

topsoil

. The intent is to restore the area to premining condi-

tion and to prevent the generation of acid mine drainage by

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Acid rain

limiting the exposure of pyrite to oxygen and water. Al-

though some minor seeps may still occur, this is the single-

most effective way to minimize the potential scale of the

problem. Mining companies are also required to monitor

the effectiveness of their restoration programs and must

post bonds to guarantee the execution of abatement efforts,

should any become necessary in the future.

There are, however, numerous abandoned sites

exposing pyrite-bearing spoils. Cleanup efforts for these sites

have focused on controlling one or more of the three condi-

tions necessary for the creation of the acidity: pyrite, bacteria,

and oxygen. Attempts to remove bulk quantities of the py-

rite-bearing mineral and store it somewhere else are ex-

tremely expensive and difficult to execute. Inhibiting the

bacteria by using

detergents

, solvents, and other bactericidal

agents are temporarily effective, but usually require repeated

application. Attempts to seal out air or water are difficult

to implement on a large scale or in a comprehensive manner.

Since it is difficult to reduce the formation of acid

mine drainage at abandoned sites, one of the most promising

new methods of mitigation treats the acid mine drainage

after it exits the mine spoil wastes. The technique channels

the acid seeps through artificially created wetlands, planted

with cattails or other wetland plants in a bed of gravel,

limestone, or compost. The limestone neutralizes the acid

and raises the pH of the drainage while the mixture of

oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor areas within the wetland pro-

mote the removal of iron and other metals from the drainage.

Currently, many agencies, universities, and private firms are

working to improve the design and performance of these

artificial wetlands. A number of additional treatment tech-

niques may be strung together in an interconnected system

of anoxic limestone trenches, settling ponds, and planted

wetlands. This provides a variety of physical and chemical

microenvironments so that each undesirable characteristic

of the acid drainage can be individually addressed and

treated, e.g., acidity is neutralized in the trenches, suspended

solids are settled in the ponds, and metals are precipitated

in the wetlands. In the United States, the research and

treatment of acid mine drainage continues to be an active

field of study in the Appalachians and in the metal-mining

areas of the Rocky Mountains.

[Usha Vedagiri]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Clay, S. “A Solution to Mine Drainage?” American Forests 98 (July-August

1992): 42-43.

Hammer, D. A. Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment: Municipal,

Industrial, Agricultural. Chelsea, MI: Lewis, 1990.

Schwartz, S. E. “Acid Deposition: Unraveling a Regional Phenomenon.”

Science 243 (February 1989): 753–763.

6

Welter, T. R. “An ’All Natural’ Treatment: Companies Construct Wetlands

to Reduce Metals in Acid Mine Drainage.” Industry Week 240 (August 5,

1991): 42–43.

Acid rain

Acid

rain is the term used in the popular press that is equiva-

lent to acidic deposition as used in the scientific literature.

Acid deposition

results from the deposition of airborne

acidic pollutants on land and in bodies of water. These

pollutants can cause damage to forests as well as to lakes

and streams.

The major pollutants that cause acidic deposition are

sulfur dioxide

(SO

2

) and

nitrogen oxides

(NO

x

) produced

during the

combustion

of

fossil fuels

. In the

atmosphere

these gases oxidize to sulfuric acid (H

2

SO

4

) and nitric acid

(HNO

3

) that can be transported long distances before being

returned to the earth dissolved in rain drops (wet deposition),

deposited on the surfaces of plants as cloud droplets, or

directly on plant surfaces (

dry deposition

). Electrical utili-

ties contribute 70% of the 20 million tons (21 million metric

tons) of SO

2

that are annually added to the atmosphere.

Most of this is from the combustion of

coal

.

Electric utilities

also contribute 30% of the 19 million tons of NO

x

added

to the atmosphere, and internal combustion engines used in

automobiles, trucks, and buses contribute more than 40%.

Natural sources such as forest fires, swamp gases, and volca-

noes only contribute 1–5% of atmospheric SO

2

. Forest fires,

lightning, and microbial processes in soils contribute about

11% to atmospheric NO

x

. In response to

air quality

regula-

tions, electrical utilities have switched to coal with lower

sulfur content and installed scrubbing systems to remove

SO

2

. This has resulted in a steady decrease in SO

2

emissions

in the United States since 1970, with a 18–20% decrease

between 1975 and 1988. Emissions of NO

x

have also de-

creased from the peak in 1975, with a 9–15% decrease from

1975 to 1988.

A commonly used indicator of the intensity of acid

rain is the

pH

of this rainfall. The pH of non-polluted

rainfall in forested regions is in the range 5.0–5.6. The upper

limit is 5.6, not neutral (7.0), because of carbonic acid that

results from the dissolution of atmospheric

carbon dioxide

.

The contribution of naturally occurring nitric and sulfuric

acid, as well as organic acids, reduces the pH somewhat to

less than 5.6. In

arid

and semi-arid regions, rainfall pH

values can be greater than 5.6 due the effect of alkaline

soil

dust in the air. Nitric and sulfuric acids in acidic rainfall

(wet deposition) can result in pH values for individual rainfall

events of less than 4.0.

In North America, the lowest acid rainfall is in the

northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. The

lowest mean pH in this region is 4.15. Even lower pH values