Elsevier Encyclopedia of Geology - vol I A-E

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

construction of which is referred to in I Kings

9 : 15,24 and 11 : 27.

The construction of embankment dams to retain

reservoirs of water has a long history. The 14 m high

Sadd-el-Kafara was built with engineered fill in Egypt

at the beginning of the age of the pyramids and im-

pounded 0.5 10

6

m

3

of water. The dam had a cen-

tral core of silty sand supported by shoulders of rock

fill. Inadequate provision was made for floods, and

the dam was probably overtopped and breached

during a flood.

Fills were placed to provide a suitable elevation for

defence or for control of the local population. The

mound for Clifford’s Tower was built in York in 1069

by William I during his campaign to subdue the north

of England. The 15 m high mound, which was built of

horizontal layers of fill comprising stones, gravel, and

clay, was founded on low-lying ground to provide a

suitable elevation for the construction of a strong-

hold. The original tower was made of timber, and

the present stone structure known as Clifford’s

Tower dates from the middle of the thirteenth cen-

tury. Soon after the erection of the stone tower, severe

floods in 1315–1316 softened the fill in the mound,

and in 1358 the tower was described as being cracked

from top to bottom in two places. These cracks,

which were repaired at great expense before 1370,

are still visible.

In many parts of the world, low-lying wet ground

has been reclaimed by filling, and in the last few

centuries this type of land reclamation has taken

place on a large scale. Reclamation of the marshes

bordering the Baltic Sea, on which St Petersburg is

built, began in 1703. On the opposite side of the

Atlantic Ocean, much of downtown Manhattan was

built on made ground created before 1900. When

present-day maps of cities are superimposed on old

maps, the extent of such made ground is revealed.

In urban locations where the land has been con-

tinuously occupied for centuries, there are likely to be

large areas of made ground. Fills have arisen inadvert-

ently from the rubble of demolished buildings and the

slow accumulation of refuse. Made ground of this

type may contain soil, rubble, and refuse and may

be very old. It can be quite extensive in area but is

often relatively shallow. Some towns in the Middle

East provide examples of the unplanned accumula-

tion of fills. The most common building material was

mud brick, and so the walls had to be thick. New

construction took place on the ruins of older build-

ings, and in Syria and Iraq villages stand on mounds

of their own making. The ruins of an ancient city may

rise 30 m above the surrounding plain.

This gradual rise of debris has been much less

common in Great Britain, although in some locations

deep fills have accumulated. By the third century AD

the Wallbrook in the City of London was already half

buried, and mosaic pavements of Roman London lie

8–9 m below the streets of the modern city.

The Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh was

completed in 1826 on the Mound, which was formed

in the late 1700s using clay spoil from the construc-

tion of the New Town. The building was founded on

square timber piles that, in the course of time, rotted

because they were above the water-table, leaving

large voids under the stone footings. Remedial

works involving compensation grouting were carried

out recently.

With the coming of the Industrial Revolution man-

kind’s capacity to generate waste materials, and to

cover significant portions of the Earth’s surface

with them, greatly increased. Where minerals were

extracted from underground workings, it was im-

practicable to avoid extracting quantities of other

materials with the desired mineral, and the result-

ing spoil was brought to the surface and placed in

heaps.

The need to supply unpolluted water to the rapidly

expanding industrial cities in the north of England led

to the construction of large numbers of embankment

dams in the nineteenth century. Dale Dyke was one of

the dams that was built to supply water to Sheffield.

The 29 m high embankment followed the traditional

British form of dam construction, with a narrow

central core of puddle clay forming the watertight

element. The reservoir capacity was 3.2 10

6

m

3

.

By 10 March 1864, during the first filling of the

reservoir, the water level behind the newly built dam

was 0.7 m below the crest of the overflow weir. In the

late afternoon of 11 March 1864 a crack was ob-

served along the downstream slope near the crest

of the dam. At 23.30 the dam was breached, and

the resulting flood destroyed property estimated to

be worth half a million pounds sterling, and caused

the loss of 244 lives. Developments in geotechnical

engineering in the twentieth century have enabled

safe embankment dams to be built with confidence.

Twentieth Century

The twentieth century saw a massive expansion of

made ground. Large-scale earthmoving machinery

made it possible to place fill rapidly and cheaply in

quantities never before experienced. This applied both

to engineered fills placed to construct embankment

dams, road embankments, and sites for buildings, and

to non-engineered fills placed as mining, industrial,

chemical, building, dredging, commercial, and do-

mestic wastes. Table 1 provides details of some fills

placed over the last 4000 years and illustrates how the

536 ENGINEERING GEOLOGY/Made Ground

scale of operations vastly increased in the twentieth

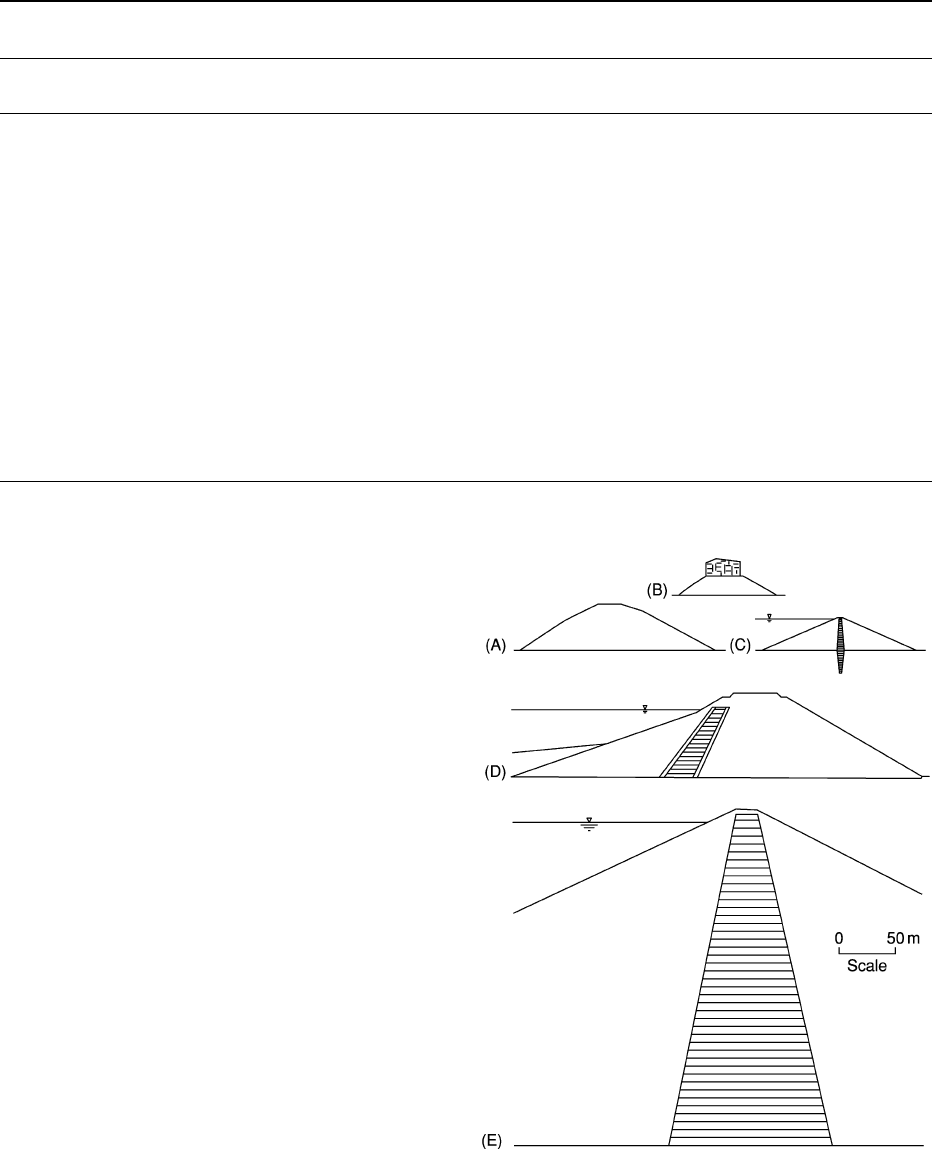

century. Cross-sections of a number of the earth struc-

tures included in Table 1 are shown in Figure 2.

Although urban redevelopment has continued

throughout history, modern programmes of urban

regeneration are carried out at a rate and on a scale

not seen before. Much of this redevelopment is

carried out on made ground.

The reclamation of land from the sea can be

achieved either by the construction of water-retaining

embankments, which prevent the sea flooding land

below sea-level, as in the Netherlands, or by the

placement of fill to form made ground whose surface

is above sea-level. Examples of the latter approach

include the massive reclamation projects carried out

in Hong Kong, Japan, and Singapore for the construc-

tion of new airports. Kansai airport is located 5 km

off the Japanese mainland, and the placement of a

33 m thickness of fill to form the island has caused the

underlying deposits to settle by 14 m. The construc-

tion of Phase 2 of Kansai airport has commenced, and

this will increase the surface area of the made ground

to 1100 ha.

The number and size of embankment dams in-

creased greatly during the twentieth century. Fort

Peck dam in the USA was built of hydraulically placed

earthfill and consequently has flat slopes and contains

a large volume of fill. When the embankment was

nearly complete, there was a slide in the upstream

slope involving 4 10

6

m

3

of fill. At the time of its

completion in 1940 it was the largest dam in the

world, and it remained so until Tarbela dam was com-

pleted in 1976 in Pakistan. Tarbela has an impervious

upstream blanket, which continues for 2 km up-

stream of the upstream toe of the dam. The 300 m

high Nurek dam in Tajikistan was completed in 1980

and is one of the world’s highest dams.

Figure 2 Fill structures: (A) Silbury Hill, England; (B) Clifford’s

Tower mound, England; (C) Dale Dyke dam, England; (D) Scam-

monden dam, England; and (E) Nurek dam, Tajikistan.

Table 1 Some examples of made ground

Structure Location Purpose Date built

Height or

depth (m)

Volume

(10

6

m

3

)

Surface

area (ha)

Silbury Hill Wiltshire, England Unknown pre-2000 BC 40 0.25 2

Sadd-el-Kafara Egypt Retain water pre-2000

BC 14 0.09 2

Clifford’s Tower mound York, England Military AD 1069 15 0.04 0.4

Dale Dyke dam Sheffield, England Retain water

AD 1864 29 0.4 4

Fort Peck dam Montana, USA Retain water

AD 1940 76 96 200

Scammonden dam Huddersfield,

England

Retain water þ motorway

embankment

AD 1969 76 4.3 15

Tarbela dam þ upstream

blanket

Pakistan Retain water AD 1976 148 118 700

Nurek dam Tajikistan Retain water

AD 1980 300 58 60

Gilow impoundment South-western

Poland

Retain copper tailings

AD 1980 22 68 540

Lounge opencast site

a

Ashby-de-la-Zouch,

England

Engineered fill for road

embankment

AD 1990 40 3.7 15

Dixon opencast site Chesterfield,

England

Backfill

AD 1992 74 16 119

Kansai airport (Phase 1) Osaka, Japan Island for airport AD 1994 33 180 510

Chek Lap Kok airport Hong Kong Platform for airport AD 1996 25 194 1248

a

Data refers only to that part of the backfill that was placed as an engineered fill.

ENGINEERING GEOLOGY/Made Ground 537

The 76 m high Scammonden dam, which was com-

pleted in 1969, is the highest embankment dam in

England. The embankment was designed to serve

the dual purpose of impounding a reservoir with a

capacity of 7.9 10

6

m

3

and carrying the M62 trans-

Pennine motorway across the Scammonden valley.

A cross-section of the embankment is shown in

Figure 2D. The shoulders were built of compacted

sandstone and mudstone rock fill, and it has an up-

stream-sloping rolled clay core in the upstream part

of the embankment.

In metal mining, rock is crushed to extract the

desired mineral, leaving large amounts of crushed

rock as a waste material. The fine waste material,

which is known as tailings, is discharged from the

wet process as a saturated slurry and commonly

pumped through a pipeline from the plant to an im-

poundment formed by an embankment dam. Large

waste-impounding embankments have been built in

the twentieth century, some more than 150 m high

and some impounding more than 10

8

m

3

of waste

materials. The Gilow impoundment in Poland has a

surface area of 540 ha. The principal hazard posed by

such dams and their retained waste impoundments is

the risk of rapid discharge of the impounded waste

material in an uncontrolled manner should there be

a breach of the embankment. There have been a

number of failures of large tailings dams in recent

years, and some waste materials pose major hazards

to the natural environment; for example, the breach

on 24 April 1998 of the Aznalcollar tailings dam at

Seville in Spain released 7 10

6

m

3

of mining

waste and water, threatening the Coto de Donana

National Park.

Where iron ore, coal, and other minerals are found

in thin seams not too far below the surface, they can

be won by opencast or strip mining; that is, the over-

lying soil or rock is excavated to reach the mineral

seams without the need for subsurface tunnelling.

When a mineral has been extracted by opencast

mining, the overburden soils and rocks are replaced

in the excavation, and these mining operations have

been major producers of deep non-engineered fills in

many parts of the world. By 1986 more than 1000

residential buildings and farms had been established

on deep uncompacted backfills in the Rhenish brown

coal area of Germany. During the 1980s opencast

coal production in Great Britain was about 14 million

tonnes per annum, and the extraction of one tonne of

coal typically involved the excavation of 15 m

3

of

overburden. Sites were often restored to agricultural

use without compaction during backfilling of the

opencast excavation, but latterly systematic compac-

tion has become more common. Two British opencast

sites are included in Table 1.

Waste from the deep mining of coal, which is

known as colliery spoil, is derived from the rocks

adjacent to the coal seams, and during mining oper-

ations quantities of these rocks, unavoidably ex-

tracted with the coal or in driving the tunnels that

give access to the coalface, are brought to the surface.

Towards the end of the twentieth century, world coal

production approached 5 10

9

tonnes per annum.

The coarse discard from coal mining used to be

dumped in heaps, which could become very large.

Following the Aberfan disaster in Wales in 1966,

when the failure of an unstable colliery spoil heap

caused great loss of life, it became the usual practice

in Great Britain to place the spoil in thin layers with

compaction. Geotechnical problems can be largely

overcome by adequate compaction during placement.

By 1974 there were 3 10

9

tonnes of colliery spoil in

Great Britain, and in 1984 the coal mining industry

produced 5 10

7

tonnes of coarse spoil annually,

which was placed in tips adjacent to the collieries. In

April 1988 there were 4700 ha of derelict land asso-

ciated with colliery spoil heaps in England alone. The

rapid decline of the coal industry in the 1990s meant

that the annual production of these wastes reduced,

but large stocks of colliery spoil remain in the coal-

fields. In 1996 it was planned to reclaim 900 ha of

colliery land for residential, commercial, and retail

uses.

A major proportion of the domestic waste gener-

ated in the UK is disposed of in landfill. In 1986, over

90% of controlled domestic, commercial, and indus-

trial solid wastes (excluding mining and quarrying

wastes) were disposed of by landfilling. In the year

1986/1987 nearly 2 10

7

tonnes of household or

domestic waste were disposed of in England and

Wales, and this figure did not change substantially

over the subsequent 10 years. Despite environmental

initiatives, landfilling has continued on a large scale.

In the USA at the end of the twentieth century

1.2 10

8

tonnes of municipal solid waste were

landfilled each year.

Functions of Made Ground

The function of non-engineered fills is to dispose of

unwanted waste material. By contrast, the large

quantities of fill material that are placed as engin-

eered fills form part of carefully controlled civil-

engineering works. Three major types of engineered

fills are embankment dams, road embankments,

and fills that support buildings.

As we have seen, embankment dams are con-

structed from fill and are built to retain reservoirs of

water, which may be required for hydropower, water

supply to towns, irrigation, or flood control. Similar

538 ENGINEERING GEOLOGY/Made Ground

embankments can be used to retain canals. An em-

bankment dam will usually be composed of several

different types of fill: a low-permeability fill to form

the watertight element, stronger fill to support the

watertight element, and fills to act as filters, drains,

and transition materials. Possible hazards affecting

the dam include internal erosion, slope instability,

and overtopping during floods.

Embankment dams are also used to retain lagoons

of sedimented waste material from mining and indus-

trial activities. If the waste is not toxic, these embank-

ments may be designed so as to allow water to drain

through. The embankment may be built in stages as

waste disposal progresses.

Another use for a special type of embankment is

to protect harbours and the shoreline from the sea.

Such embankments are often built as rubble-mound

breakwaters and require high-quality quarried rock

for the fill. Placement to the required profile presents

obvious difficulties.

Embankments to carry roads and railways are usu-

ally built to reduce gradients. The engineered fills use

material excavated from adjacent cuttings during the

cut-and-fill operations, so there is limited scope for

material selection and whatever is excavated has to be

placed in the adjacent embankment unless it is clearly

unsuitable. In England, during the construction of the

M6 motorway between Lancaster and Penrith in the

1960s, much of the soil excavated along the line of

the road was very wet, and a geotechnical design was

developed that involved the use of drainage layers

built into the embankment during construction.

Buildings may be founded on made ground. Old

excavations are infilled, and sometimes embank-

ments are built above the level of the surrounding

ground. The objective is to support buildings safely

while minimizing the risk of damaging settlement,

and, where structures sensitive to settlement are to

be built on made ground, a high-quality fill that is not

vulnerable to large post-construction movement is

required.

Opencast-mining sites have often been restored

for agricultural use, but where the sites are close to

urban areas they may subsequently be used for hous-

ing and commercial developments. Loose backfill

usually has considerable settlement potential, and

some existing areas of loose fill have been improved

by preloading with a temporary heavy surcharge of

fill. Because of the free-draining nature of the loose

fill, it soon consolidates, and this type of treatment

has made some sites quite suitable for normal hous-

ing. Where building is foreseen prior to backfilling an

opencast mining site, the fill material should be

placed in thin layers and heavily compacted as an

engineered fill.

Fill Placement

There are two basic elements in the quality manage-

ment of engineered fills: placement of a fill with the

required quality; and evidence that the fill has the re-

quired quality. Both an appropriate specification and

rigorous quality-control procedures are required. It is

not possible to prevent some variability in the made

ground, as there will be a degree of heterogeneity in

the source material and some segregation during

placement. It is necessary to determine how the re-

quired properties can be achieved with an acceptable

degree of uniformity.

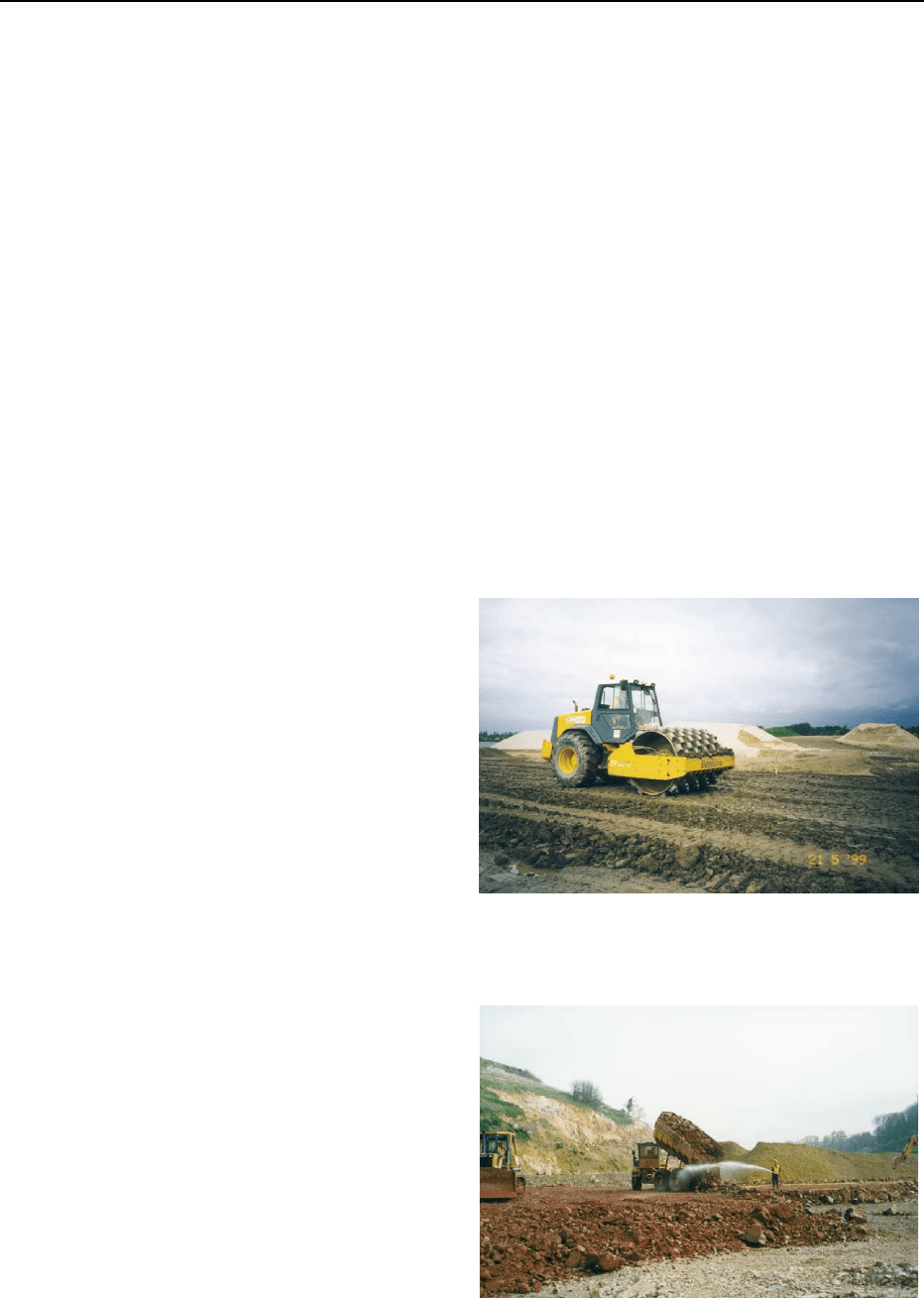

Placement in thin layers with heavy compaction at

an appropriate water content is the method usually

adopted to obtain the required performance from an

engineered fill used in dam, road, or foundation ap-

plications. Figure 3 shows the compaction of a clay

fill, and Figure 4 shows a rock fill being watered

during placement. There are three basic approaches

to the specification of engineered fills.

Figure 3 Compacting clay fill.

Figure 4 Watering rock fill during placement.

ENGINEERING GEOLOGY/Made Ground 539

.

In a method specification, the procedure for place-

ment and compaction is described. The type and

mass of the compactor, the number of passes,

and the layer thickness are specified. Reliance is

placed on close inspection to ensure compliance

with the specification.

.

An end-product specification is based on required

values for properties of the fill as it is placed. The

basic measurements of the in situ state of compac-

tion are density and water content, but these meas-

urements on their own are not adequate indicators

– the density needs to be interpreted in terms of the

density at a specified water content under some

standard type of compaction. For a clay fill, the

specification could be in terms of percentage air

voids or undrained shear strength. Compliance is

tested as filling progresses.

.

In a performance specification some facet of the

post-construction behaviour of the fill is specified,

such as a permissible post-construction settlement

or a load-test result. With this approach the speci-

fication is directly related to one or more aspects of

the performance requirements.

Non-engineered fills have usually been placed in

the simplest and cheapest way feasible. The fill may

have been tipped in high lifts with no systematic

compaction. A non-engineered fill can be effectively

converted to an engineered fill by in situ ground

treatment subsequent to the completion of fill place-

ment, although the limitations of such post-construc-

tion treatment should be recognized, since unsuitable

fill material is still present after treatment and most

forms of compaction applied to the ground surface

are effective only to a limited depth.

Natural fine soils or waste materials can be mixed

with enough water to enable them to be transported

in suspension. Usually the suspension is pumped

through a pipe and then discharged onto the surface

being filled. The deposit is described as hydraulic fill.

Figure 5 shows a lagoon of pulverized fuel ash; this

waste product from coal-fired power stations has

been mixed with sufficient water to enable it to be

pumped to the lagoon.

Where a waste material contains particles of differ-

ent sizes, segregation may occur during deposition.

As the suspension flows away from the discharge

point, the larger soil particles settle out almost imme-

diately and the water and fines flow away. Eventually,

the fine material also settles out but at a much greater

distance from the discharge point. The placement of

hydraulic sand fills beneath water involves settling

from a slurry, and such subaqueous hydraulic fills

can be placed by bottom dumping from a barge or

by pipeline placement.

Fill Properties and Behaviour

The required behaviour of made ground is closely

linked to the purpose of the engineered fill and the

processes and hazards to which it may be exposed.

There may be performance requirements that can

be expressed in terms of a wide range of geotech-

nical properties, such as shear strength, stiffness,

compressibility, and permeability.

Made ground exhibits as wide a range of engineer-

ing properties as does natural ground; both the nature

of the fill material and the mode of formation have a

major influence on subsequent behaviour. Needless to

say, there is a vast difference between the behaviour

of an engineered heavily compacted sand-and-gravel

fill and that of recently placed domestic refuse. Made

ground may have been formed by fill placed in thin

layers and heavily compacted or by fill end-tipped in

high lifts under dry conditions or into standing water.

The method of placement affects the density of the fill

and the homogeneity of the made ground. Many of

the problems with non-engineered fills are related to

their heterogeneity. Depending on the method of

placement and the degree of control exercised during

placement, there may be variability in materials,

density, and age.

The engineering properties of hydraulic fills can be

expected to be very different from the properties of

fills placed at lower water contents under dry condi-

tions. Hydraulic transport and deposition of mater-

ials generally produces fills with a high water content

in a relatively loose or soft condition. Segregation of

different particle sizes is likely.

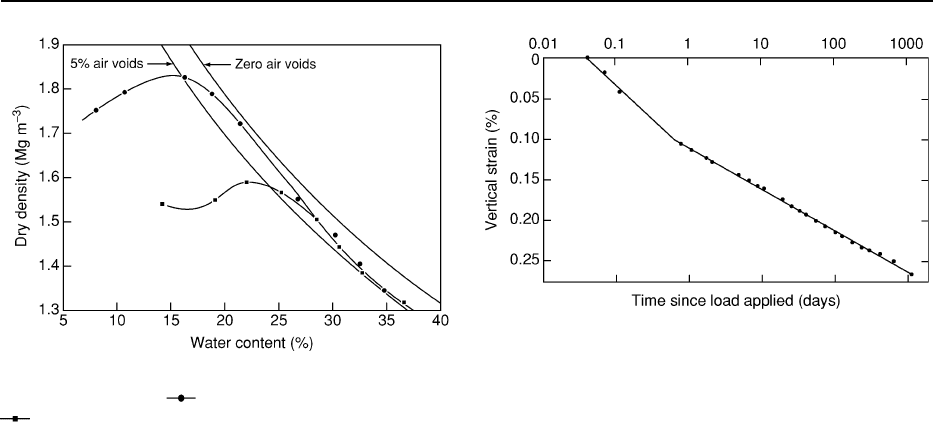

The amount of densification of a clayey soil that

can be achieved for a given compactive effort is a

function of water content. Laboratory compaction-

test results are plotted as the variation of dry density

with water content. Such plots are a simple and useful

way of representing the condition of a partially

Figure 5 Lagoon filled with pulverized fuel ash.

540 ENGINEERING GEOLOGY/Made Ground

saturated fill and can be used to identify two param-

eters of prime interest – the maximum dry density and

the corresponding optimum water content. The terms

maximum dry density and optimum water content

refer to a specified compaction procedure and can

be misleading if taken out of the context of that

procedure. Figure 6 shows laboratory test results

using two different compactive efforts. The heavier

compaction produces a greater maximum dry density

at a lower optimum water content. At a water content

less than optimum, the specified compaction pro-

cedure may result in a fill with large air voids. At a

water content significantly higher than optimum, the

specified compaction procedure should produce a fill

with a minimum of air voids, typically between 2%

and 4%.

Where made ground is built upon, the magnitude

and rate of long-term settlement is an important issue.

Fill will undergo some creep compression, which

occurs without changes in the load applied to the fill

or the water content of the fill. For many fills there is

a linear relationship between creep compression and

the logarithm of the time that has elapsed since the

load was applied. This type of relationship can be

characterized by the parameter a, which is the vertical

compression occurring during a log cycle of time

(i.e. between, say, 1 year and 10 years). For loosely

placed coarse fills, a is typically between 0.5% and

1%. For heavily compacted fills, a is much smaller

and strongly dependent on stress. Figure 7 shows the

rate of compression of a heavily compacted sandstone

rock fill measured in a large laboratory oedometer

test under a constant vertical applied stress of

0.7 MPa. From 1 day to 1000 days after the load

was applied there was a linear relationship between

creep compression and the logarithm of elapsed time,

corresponding to a ¼ 0.05%.

When first inundated, most types of partially satur-

ated fill are susceptible to collapse compression if they

have been placed in a relatively loose or dry condition.

This reduction in volume can occur under a wide

range of stresses and without a change in applied

total stress. For buildings on fill, the risk of collapse

compression is normally the main concern; where it

occurs after construction has taken place, buildings

may be seriously damaged. The causes of collapse

compression on inundation fall into three categor-

ies: weakening of interparticle bonds; weakening of

particles in coarse fills; and softening of lumps of

clay in fine fills. Inundation can result from a rising

groundwater table or from downward infiltration of

surface water. An important objective of the specifi-

cation and control procedures adopted for fills is

to eliminate or at least minimize the potential for

collapse compression.

Future Trends

It may be questioned whether the massive increase in

the generation of fill materials that occurred in the

twentieth century can or should continue. Large-scale

earthmoving, which is visually intrusive and involves

major modifications to the environment, is meeting

increasing opposition, particularly where large dams

are built. The principal objection to new dams has

centred on the flooding of large tracts of land, but all

engineering projects involving major earthmoving are

likely to face similar opposition. While it is not un-

reasonable for earthmoving projects to be subjected

to close scrutiny, it is important that the benefits

conferred by many types of made ground are not

overlooked.

Carefully controlled engineered fill is likely to form

only a small fraction of new made ground, the bulk of

which will be created by the landfilling of various

types of waste material. Every year, billions of tonnes

Figure 7 Creep compression of heavily compacted sample of

sandstone rock fill.

Figure 6 Laboratory compaction of clay fill using two differ-

ent compactive efforts.

, Heavy compaction (4.5 kg rammer);

, Standard Proctor compaction (2.5 kg rammer).

ENGINEERING GEOLOGY/Made Ground 541

of solid waste are generated by industrial and mining

activities and deposited either as spoil heaps on the

surface of the ground or as waste dumps within ex-

cavations. Mining has brought much prosperity to

human societies, but it is now widely questioned

whether these activities, which are being carried out

on an unprecedented scale, are sustainable and

whether such massive quantities of waste are environ-

mentally acceptable. Despite the huge rate of con-

sumption during the twentieth century, the known

resources of many minerals have increased rather

than diminished as new sources have been identified.

It seems probable that, for the foreseeable future, the

needs of successive generations will require the ex-

traction of minerals from the surface of the Earth on a

large scale and that there will be sufficient resources

to meet this demand. These mining operations will

mean that spoil heaps and waste dumps will cover

ever greater portions of the Earth’s surface.

While increased concern over environmental

issues is not likely to halt the industrial and mining

activities that generate waste, it will have a major

effect on waste disposal. In most countries, plans

for reclamation of the land must be approved before

mining begins, and it is usually required that the

land will be restored as closely as possible to its

original state. Environmental factors will increasingly

influence how, where, and in what form waste fills

are deposited and the treatment that such deposits

receive. There will be increasing pressure to reduce

the amount of domestic waste that is placed as

landfill.

See Also

Engineering Geology: Geological Maps; Natural and

Anthropogenic Geohazards; Liquefaction; Site and

Ground Investigation; Subsidence. Environmental Geol-

ogy. Geotechnical Engineering. Soil Mechanics.

Urban Geology.

Further Reading

Charles JA and Watts KS (2001) Building on Fill: Geotech-

nical Aspects, 2nd edn. Building Research Establishment

Report BR 424. Garston: BRE Bookshop.

Charles JA and Watts KS (2002) Treated Ground: Engin-

eering Properties and Performance. Report C572.

London: CIRIA.

Clarke BG, Jones CJFP, and Moffat AIB (eds.) (1993)

Engineered Fills. Proceedings of conference held in

Newcastle-upon-Tyne, September 1993. London: Thomas

Telford.

Grace H and Green PA (1978) The use of wet fill for the

construction of embankments for motorways. In: Clay

Fills. Proceedings of conference held in London, Novem-

ber 1978, pp. 113–118. London: Institution of Civil

Engineers.

Johnston TA, Millmore JP, Charles JA, and Tedd P (1999)

An Engineering Guide to the Safety of Embankment

Dams in the United Kingdom, 2nd edn. Building Re-

search Establishment Report BR 363. Garston: BRE

Bookshop.

Lomborg B (2001) The Skeptical Environmentalist: Meas-

uring the Real State of the World. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Matsui T, Oda K, and Tabata T (2003) Structures on and

within man-made deposits – Kansai airport. In: Vanicek I,

Barvinek R, Bohac J, Jettmar J, Jirasko D, and Salak J

(eds.) Geotechnical Problems with Man-made and Man

Influenced Ground. Proceedings of the 13th European

Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical

Engineering, Prague, vol. 3, pp. 315–328. Prague: Czech

Geotechnical Society.

Parsons AW (1992) Compaction of Soils and Granular

Materials: A Review of Research Performed at the Trans-

port Research Laboratory. London: HMSO.

Penman ADM (2002) Tailings dam incidents and new

methods. In: Tedd P (ed.) Reservoirs in a Changing

World. Proceedings of the 12th Conference of the British

Dam Society, Dublin, pp. 471–483. London: Thomas

Telford.

Perry J, Pedley M, and Reid M (2001) Infrastructure

Embankments – Condition Appraisal and Remedial

Treatment. CIRIA Report C550. London: CIRIA.

Proctor RR (1933) Fundamental principles of soil compac-

tion. Engineering News Record 111: 245–248.

Rosenbaum MS, McMillan AA, Powell JH, et al. (2003)

Classification of artificial (man-made) ground. Engineer-

ing Geology 69: 399–409.

Schnitter NJ (1994) A History of Dams: The Useful Pyra-

mids. Rotterdam: Balkema.

Trenter NA and Charles JA (1998) A model specification

for engineered fills for building purposes. Proceedings

of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Geotechnical

Engineering 119: 219–230.

542 ENGINEERING GEOLOGY/Made Ground

Problematic Rocks

F G Bell, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, UK

ß 2005, Elsevier Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

As far as engineering behaviour is concerned, a dis-

tinction has to be made between rock as a material and

the rock mass. ‘Rock’ usually refers to the intact rock,

which may usually be considered as a continuum, that

is, as a polycrystalline solid consisting of an aggregate

of minerals or grains with void or pore space. The

properties of intact rock are governed by the phys-

ical properties of the materials of which it is composed

and by the manner in which they are bonded to-

gether. The properties that influence the engineering

behaviour of rock material therefore include its

mineralogical composition, texture, fabric, minor

lithological characteristics, degree of weathering or

alteration, density, porosity, strength, hardness, in-

trinsic (or primary) permeability, seismic velocity,

and modulus of elasticity. Swelling and slaking are

taken into account where appropriate, for example

in argillaceous rocks.

On the other hand, a ‘rock mass’ includes the fis-

sures and flaws as well as the rock material and may

be regarded as a discontinuum of rock material tran-

sected by discontinuities. A discontinuity is a plane of

weakness within the rock mass, across which the rock

material is structurally discontinuous. Although dis-

continuities are not necessarily planes of separation,

most of them are, and they possess little or no tensile

strength. Discontinuities vary in size from small fis-

sures to huge faults. The most common discontinu-

ities in all rocks are joints and bedding planes. Other

important discontinuities are planes of cleavage

and schistosity, which occur in some metamorphic

rock masses, and lamination, in some sedimentary

rock masses. Obviously, discontinuities will have a

significant influence on the engineering behaviour of

rock in the ground. Indeed, the behaviour of a rock

mass is, to a large extent, determined by the type,

spacing, orientation, and characteristics of the dis-

continuities present. As a consequence, the param-

eters that should be used when describing a rock

mass include the nature and geometry of the dis-

continuities, as well as overall strength, deformation

modulus, secondary permeability, and seismic

velocity of the rock mass.

The Influence of Weathering on

Engineering Behaviour

The process of weathering represents an adjust-

ment of the constituent minerals of a rock to the

conditions prevailing at the surface of the Earth

(see Weathering). Importantly, in terms of engin-

eering behaviour, weathering weakens the rock

fabric and exaggerates any structural discontinuities,

thereby further aiding the breakdown processes.

Rock may become more friable as a result of the

development of fractures both between and within

grains. Also, some weathered material may be re-

moved, leaving a porous framework of individual

grains.

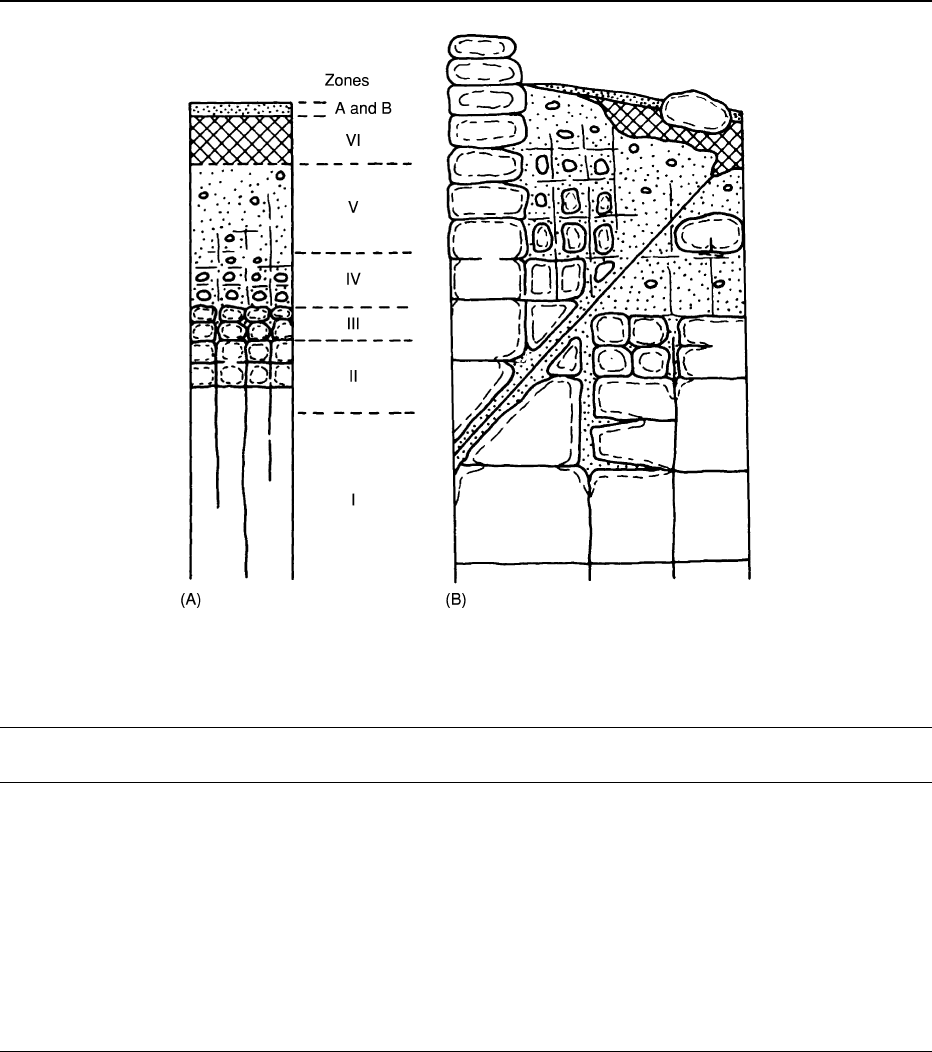

Weathering is controlled by the presence of discon-

tinuities because these provide access for the agents of

weathering. Some of the earliest effects of weathering

are seen along discontinuity surfaces. Weathering then

proceeds inwards, so that the rock mass may develop

a marked heterogeneity, with cores of relatively

unweathered material within a highly weathered

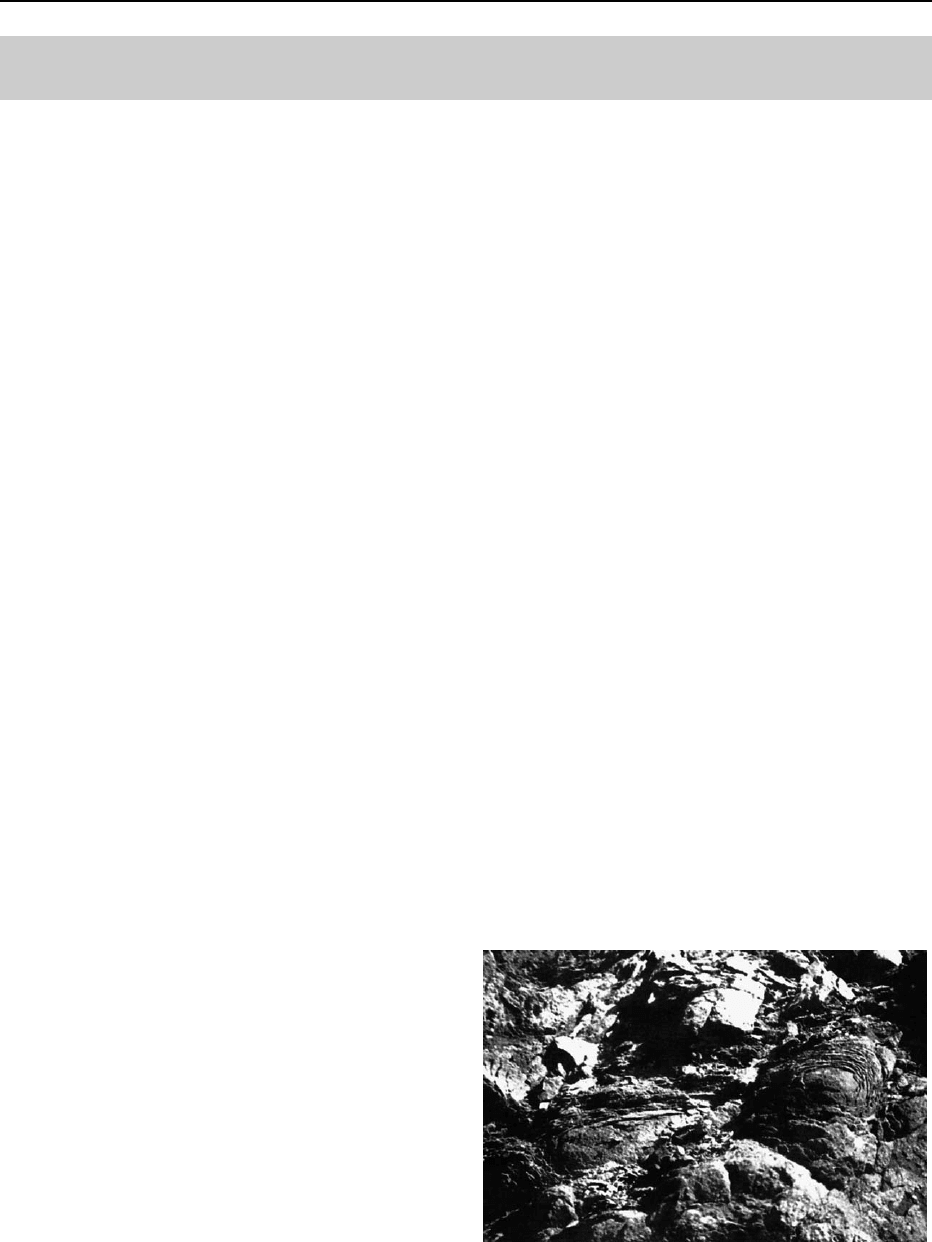

matrix (Figure 1). Ultimately, the whole of the rock

mass can be reduced to a residual soil.

Weathering generally leads to a decrease in density

and strength and to an increase in the deformability

of the rock mass. An increase in the mass permeability

frequently occurs during the initial stages of weather-

ing owing to the development of fractures, but, if clay

material is produced as minerals break down, the

permeability may be reduced. Widening of discon-

tinuities and the development of karstic features in

carbonate rock masses lead to a progressive increase

Figure 1 Weathered basalt showing corestones with spher-

oidal weathering; basalt plateau, northern Lesotho.

ENGINEERING GEOLOGY/Problematic Rocks 543

in secondary permeability. Weathering of carbonate

and evaporite rock masses takes place primarily by

dissolution. The dissolution is concentrated along

discontinuities, which are thereby enlarged. Continu-

ing dissolution ultimately leads to the development of

sinkholes and cavities within the rock mass.

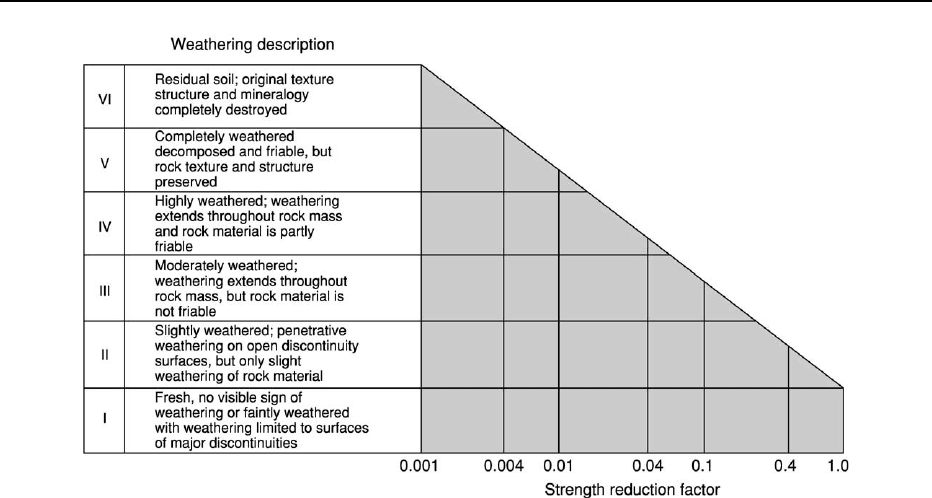

The grade of weathering refers to the stage that the

weathering has reached. This varies between fresh

rock on the one hand and residual soil on the other.

Generally, about six grades of weathering are recog-

nized, which, in turn, can be related to engineering

performance (Figure 2). One of the first classifica-

tions of the engineering grade of weathering was

devised for granite found in the vicinity of the Snowy

Mountains hydroelectric power scheme in Australia.

Subsequently, similar classifications have been de-

veloped for different rock types. Usually, rocks of the

various grades lie one above the other in a weathered

profile developed from a single rock type, the highest

grade being found at the surface (Figure 3). However,

this is not necessarily the case in complex geological

conditions. Such a classification can be used to pro-

duce maps, sections, or models showing the distribu-

tion of the grade of weathering at a particular site.

The dramatic effect of weathering on the strength

of a rock is illustrated, according to the grade of

weathering, in Figure 2.

Igneous and Metamorphic Rocks

Intrusive igneous rocks in their unaltered (unweath-

ered) state are generally sound and durable, with

adequate strength for any engineering requirement

(Table 1). In some instances, however, they may be

highly altered by weathering or hydrothermal pro-

cesses (Figure 4). Furthermore, fissure zones are by

no means uncommon in granites. Such granite rock

masses may be highly fragmented along these zones;

indeed, the granite may be reduced to sand-sized ma-

terial and/or have undergone varying degrees of kao-

linization (development of clay minerals). Generally,

the weathered products of plutonic rocks have a large

clay content. Granitic rocks can sometimes be porous

and may have a permeability comparable with that of

medium-grained sand. Some saprolites derived from

granites that have been weathered in semi-arid cli-

mates may develop a metastable fabric and therefore

be potentially collapsible. They may also be disper-

sive. Joints in plutonic rocks are often quite regular

steeply dipping structures. Sheet joints tend to be ap-

proximately parallel to the topographical surface and

develop as a result of stress relief following erosion

(Figure 5). Consequently, they may introduce a dan-

gerous element of weakness into valley slopes. The

engineering properties and behaviour of gneisses are

similar to those of granites.

Turning to extrusive igneous rocks, generally

speaking, older volcanic rocks are not problematical;

for instance, ancient lavas normally have strengths in

excess of 200 MPa (Table 1). However, younger vol-

canic deposits have, at times, proved treacherous.

This is because they often consist of markedly aniso-

tropic sequences, in which lavas (generally strong),

pyroclastics (generally weak or loose), and mudflows

Figure 2 Generalized strength reduction due to increasing grade of weathering.

544 ENGINEERING GEOLOGY/Problematic Rocks

are interbedded. Hence, foundation problems arise in

volcanic sequences because weak beds of ash, tuff,

and mudstone (formed from lahars) occur within lava

piles, giving rise to problems of differential settlement

and sliding. In addition, some volcanic materials

weather relatively rapidly, so that weathering during

periods of volcanic inactivity may readily lead to

weakening and the development of soils, which are

of much lower strength.

Clay minerals may be formed within newly erupted

basaltic rocks by the alteration of primary minerals.

Their presence can mean that the parent rhyolite,

andesite, or basalt breaks down rapidly once exposed.

The disintegration is exacerbated by the swelling of

Table 1 Geotechnical properties of some British igneous and metamorphic rocks

Specific gravity

Unconfined compressive

strength (MPa)

a

Young’s modulus

(GPa)

b

Mount Sorrel Granite (Leicestershire) 2.68 176.4 (VS) 60.6 (VL)

Eskdale Granite (Cumbria) 2.65 198.3 (VS) 56.6 (L)

Dalbeattie Granite (Kirkcudbrightshire) 2.67 147.8 (VS) 41.1 (L)

Markfieldite (Leicestershire) 2.68 185.2 (VS) 56.2 (L)

Granophyre (Cumbria) 2.65 204.7 (ES) 84.3 (VL)

Andesite (Somerset) 2.79 204.3 (ES) 77.0 (VL)

Basalt (Derbyshire) 2.91 321.0 (ES) 93.6 (VL)

Slate

c

(North Wales) 2.67 96.4 (S) 31.2 (L)

Slate

d

(North Wales) — 72.3 (S) —

Schist

c

(Aberdeenshire) 2.66 82.7 (S) 35.5 (L)

Schist

d

(Aberdeenshire) — 71.9 (S) —

Gneiss (Aberdeenshire) 2.66 162.0 (VS) 46.0 (L)

Hornfels (Cumbria) 2.68 303.1 (ES) 109.3 (VL)

a

Classification of strength: ES, extremely strong, over 200 MPa; VS, very strong, 100–200 MPa; S, strong, 50–100 MPa.

b

Classification of deformability: VL, very low, over 60 GPa; L, low, 30–60 GPa.

c

Tested normal to cleavage or schistosity.

d

Tested parallel to cleavage or schistosity.

Figure 3 Weathering profile: (A) idealized profile; and (B) more complex profile.

ENGINEERING GEOLOGY/Problematic Rocks 545