Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

system based on the Meiji Constitution of 1890 began to

evolve along Western pluralistic lines, and a multiparty

system took shape. The economic and social reforms

launched during the Meiji era led to increasing prosperity

and the development of a modern industrial and com-

mercial sector.

Experiment in Democracy

During the first quarter of the twentieth century, Japanese

political parties expanded their popular following and

became increasingly competitive. Individual pressure

groups began to appear in Japanese society, along with an

independent press and a bill of rights. The influence of

the old ruling oligarchy, the genro, had not yet been sig-

nificantly challenged, however, nor had that of its ideo-

logical foundation, the kokutai.

These fragile democratic institutions were able to

survive throughout the 1920s. During that period, the

military budget was reduced, and a suffrage bill enacted

in 1925 granted the vote to all Japanese males, thus

continuing the process of democratization begun earlier

in the century. Women remained disenfranchised; but

women’s associations gained increasing visibility during

the 1920s, and many women were active in the labor

movement and in campaigning for various social reforms.

But the era was also marked by growing social tur-

moil, and two opposing forces within the system were

AN ARRANGED MARRIAGE

Under Western influence, Chinese social customs

changed dramatically for many urban elites in the

interwar years. A vocal women’s movement, in-

spired in part by translations of Henrik Ibsen’s play

A Doll’s House, campaigned aggressively for universal suffrage

and an end to sexual discrimination. Some progressives called

for free choice in marriage and divorce and even for free love.

By the 1930s, the government had taken some steps to free

women from patriarchal marriage constraints and realize sexual

equality. But life was generally unaffected in the villages, where

traditional patterns held sway. This often created severe ten-

sions between older and younger generations, as this passage

by the popular twentieth-century novelist Ba Jin shows.

Q

Why does Chueh-hsin comply with the wishes of his

father in the matter of his marriage? Why were arranged

marriages so prevalent in traditional China?

606 CHAPTER 24 NATIONALISM, REVOLUTION, AND DICTATORSHIP

Text not available due to copyright restrictions

gearing up to challenge the prevailing wisdom. On the

left, a Marxist labor movement began to take shape in the

early 1920s in response to growing economic difficulties.

On the right, ultranationalist groups called for a rejection

of Western models of development and a more militant

approach to realizing national objectives.

This cultural conflict between old and new, native

and foreign, was reflected in literature. Japanese self-

confidence had been restored after the victories over

China and Russia and launched an age of cultural crea-

tivity in the early twentieth century. Fascination with

Western literature gave birth to a striking new genre

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

O

UT OF THE DOLL’S HOUSE

In Henrik Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House, published

in 1879 and excerpted on page 503, Nora Helmer

informs her husband, Torvald, that she will no

longer accept his control over her life and an-

nounces her intention to leave home to start her life anew.

When the outraged Torvald cites her sacred duties as

wife and mother, Nora replies that

she has other duties just as sacred,

those to herself. ‘‘I can no longer

content myself with what most peo-

ple say,’’ she declares. ‘‘I must

think over things for myself and get

to understand them.’’

To Ibsen’ s contemporaries, such remarks

were revolutionary. In nineteenth-

century Europe, the traditional charac-

terization of the sexes, based on gender-

defined social roles, had been elevated

to the status of a universal law. As the

family wage earners, men were expected

to go off to work, while women were

assigned the responsibility of caring for

home and family. Women were advised

to accept their lot and play their role as

effectively and as gracefully as possible.

In other parts of the world, women

generally had even fewer rights in com-

parison with their male counterparts.

Often, as in traditional China, they

were viewed as a sex object.

The ideal, however, did not always match reality. With the ad-

vent of the Industrial Revolution, many women, especially those

from the lower classes, were driven by the need for supplemental in-

come to seek employment outside the home, often in the form of

menial labor. Some women, inspired by the ideals of human dignity

and freedom expressed during the Enlightenment and the French

Revolution, began to protest against a tradition of female inferiority

that had long kept them in a ‘‘doll’s house’’ of male domination and

to claim equal rights before the law.

The movement to liberate women from the iron cage of legal

and social inferiority first began to gain ground in English-speaking

countries such as Great Britain and the United States, but it gradu-

ally spread to the continent of Europe and then to colonial areas

in Africa and Asia. By the first decades of the twentieth century,

women’s liberation movements were under way in parts of North

Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia,

voicing a growing demand for access

to education, equal treatment before

the law, and the right to vote. No-

where was this more the case than in

China, where a small minority of edu-

cated women began to agitate for

equal rights with men.

Progress, however, was often

agonizingly slow, es pecially in soci e-

ties where age-old traditional values

had not yet been undermined by the

corrosive force of the Industrial Revo-

lution. In m any colonial societies, the

effort to improve the condition of

women wa s subordinated to the goal

of gaining national independence. In

some instances, women’s liberation

movements were led by educa ted

elites who failed to include the con-

cerns of working-class women in their

agendas. Colonialism, too, was a

double-edged sword, as the sexist bias

of European officials combined with

indigenous traditions of male superi-

ority to margi nalize women even further. As men moved to the

cities to exploit opportunities provided by the new colonial admin-

istra tion, women were left to cope with their traditional responsibil-

ities in the villages, often without the safety net of male support

that had sustained them during the precolonial era.

Q

From the information available to you, do you believe that

the imperialist policies applied in colonial territories served to

benefit the cause of women’s rights or not?

The Chinese ‘‘Doll’s House.’’ A woman in traditional

China binding her feet

c

The Art Archive/Marc Charmet

JAPA N BETWEEN THE WARS 607

called the ‘‘I novel.’’ Defying traditional Japanese reti-

cence, some authors reveled in self-exposure with con-

fessions of their innermost thoughts. Others found release

in the ‘‘proletarian literature’’ movement of the early

1920s. Inspired by Soviet literary examples, these authors

wanted literature to serve socialist goals in order to im-

prove the lives of the working class. Finally, some Japanese

writers blended Western psychology with Japanese sensi-

bility in exquisite novels reeking with nostalgia for the old

Japan. One well-known example is Junichiro Tanizaki’s

Some Prefer Nettles, published in 1929, which delicately

juxtaposed the positive aspects of both traditional and

modern Japan. By the 1930s, however, military censorship

increasingly inhibited free literary expression.

A Zaibatsu Economy

Japan also continued to make impressive progress in

economic development. Spurred by rising domestic de-

mand as well as continued government investment in the

economy, the production of raw materials tripled between

1900 and 1930, and industrial production increased more

than twelvefold. Much of the increase went into exports,

and Western manufacturers began to complain about

increasing competition from the Japanese.

As often happens, rapid industrialization was ac-

companied by some hardship and rising social tensions.

In the Meiji model, various manufacturing processes were

concentrated in a single enterprise, the zaibatsu, or fi-

nancial clique. Some of these firms were existing mer-

chant companies that had the capital and the foresight to

move into new areas of opportunity. Others were formed

by enterprising samurai, who used their status and ex-

perience in management to good account in a new en-

vironment. Whatever their origins, these firms, often with

official encouragement, gradually developed into large

conglomerates that controlled a major segment of the

Japanese economy. By 1937, the four largest zaibatsu

(Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, and Yasuda) controlled

21 percent of the banking industry, 26 percent of mining,

35 percent of shipbuilding, 38 percent of commercial

shipping, and more than 60 percent of paper manu-

facturing and insurance.

This concentration of power and wealth in a few major

industrial combines created problems in Japanese society .

In the first place, it resulted in the emergence of a dual

economy: on the one hand, a modern industry character-

ized by up-to-date methods and massive government

subsidies, and on the other, a traditional manufacturing

sector characterized by conservative methods and small-

scale production techniques.

Concentration of wealth also led to growing eco-

nomic inequalities. As we have seen, economic growth

had been achieved at the expense of the peasants, many of

whom fled to the cities to escape rural poverty. That labor

surplus benefited the industrial sector, but the urban

proletariat was still poorly paid and ill-housed. A rapid

increase in population (the total population of the

Japanese islands increased from an estimated 43 million

in 1900 to 73 million in 1940) led to food shortages and

the threat of rising unemployment. In the meantime,

those left on the farm continued to suffer. As late as the

The Grea t T okyo Ea rthquake. On

September 1, 1923, a massive earthquake

struck the central Japanese island of

Honshu, causing more than 130,000 deaths

and virtually demolishing the capital city of

Tokyo. Though the quake was a national

tragedy, it also came to symbolize the

ingenuity of the Japanese people, whose

efforts led to a rapid reconstruction of the

city in a new and more modern style.

That unity of national purpose would be

demonstrated again a quarter of a century

later in Japan’s swift recovery from the

devastation of World War II.

c

Getty Images

608 CHAPTER 24 NATIONALISM, REVOLUTION, AND DICTATORSHIP

beginning of World War II, an estimated one-half of all

Japanese farmers were tenants.

Shidehara Diplomacy

A final problem for Japanese leaders in the post-Meiji

era was the familiar dilemma of finding sources of raw

mate rials and foreign markets for the nation’s manu-

fact ured goods. Until World War I, Japan had dealt with

the problem by seizing territories such as Taiwan, Korea,

and southern Man churia and transforming them into

colonies or protectorates of the growing Japanese e m-

pire. That policy had begun to arouse the concern, and

in some cases th e hostility, of the Western nations. China

was also becoming ap prehensive; as we have seen,

Japanese demands for Shandon g Province at the Paris

Peace Conference in 1919 aroused massive protests in

major Chinese cities.

The United States was especially concern ed about

Japanese aggressiveness. Although th e United States had

been less active than some European states in pursuing

colonies in the Pacific, it had a strong interest in keeping

the area open for U.S. comme rcial activities. In 1922, in

Washington, D.C., the United States convened a major

conference of nations with interests in the Pacific to

discuss problems of regional security. The Washington

Conference led to agreements on several issu es, but the

major accomplishment was a nine-power treaty recog-

nizing the territorial integrity of China and the Open

Door. The other participants induced Japan to accept

these provisions by accepting its special position in

Manchuria.

During the remainder of the 1920s, Japanese gov-

ernments attempted to play by the rules laid down at the

Washington Conference. Known as Shidehara diplomacy,

after the foreign minister (and later prime minister) who

attempted to carry it out, this policy sought to use dip-

lomatic and economic means to realize Japanese interests

in Asia. But this approach came under severe pressure as

Japanese industrialists began to move into new areas,

such as heavy industry, chemicals, mining, and the

manufacturing of appliances and automobiles. Because

such industries desperately needed resources not found in

abundance locally, the Japanese government came under

increasing pressure to find new sources abroad.

In the early 1930s, with the onset of the Great

Depression and gro wing tensions in the international

arena, nationalist forces rose to dominance in the gov-

ernment. Whereas party leaders during the 1920s had at-

tempted to realize Japanese aspirations within the existing

global political and economic framework, the dominant

elements in the government in the 1930s, a mixture of

military officers and ultranationalist politicians, were

con vinced that the diplomacy of the 1920s had failed; they

advocated a more aggressive approach to protecting na-

tional interests in a brutal and competitive world.

(see Chapter 25).

Nationalism and Dictatorship

in Latin America

Q

Focus Questions: What problems did the nations of

Latin America face in the interwar years? To what

degree were they a consequence of foreign influence?

Although the nations of Latin America played little role in

World War I, that conflict nevertheless exerted an impact

on the region, especially on its economy. By the end of the

1920s, the region was also strongly influenced by another

event of global proportions---the Great Depression.

A Changing Economy

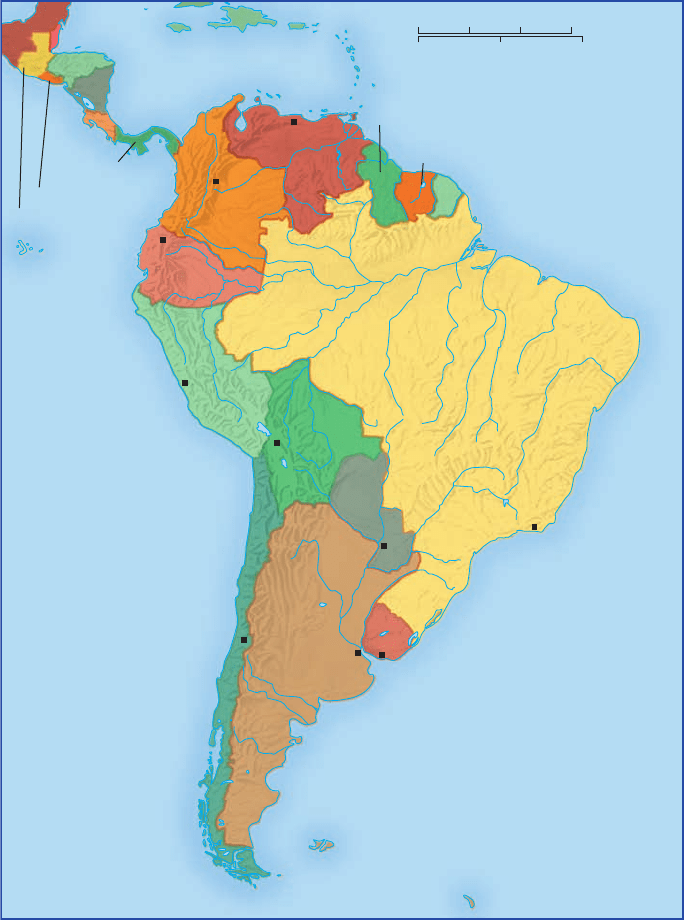

At the beginning of the twentieth century, virtually all of

Latin America, except for the three Guianas, British

Honduras, and some of the Caribbean islands, had

achieved independence (see Map 24.2). The economy of the

region was based largely on the export of foodstuffs and

raw materials. Some countries relied on exports of only

one or two products. Argentina, for example, exported

primarily beef and wheat; Chile, nitrates and copper;

Brazil and the Caribbean nations, sugar; and the Central

American states, bananas. A few reaped large profits from

these exports, but for the majority of the population, the

returns were meager.

The Role of the Yankee Dollar World War I led to a

decline in European investment in Latin America and a

rise in the U.S. role in the local economies. By the lat e

1920s, the United States had replaced Great Br itain as

the foremost source of i nvestment in Latin America.

Unlike the British, however, U.S. i nvestors put their

funds directly into production enterprises, causing large

segments of the area’s export industries to fall into

American hands. A number of Central American states,

for example, were popularly labeled ‘‘banana republics’’

because of the power and influence of the U.S.-owned

United Fruit Company. American firms also dominated

the copper mining in dustry in Chile and Peru and the oil

industry in Mexico, Peru, and Bolivia.

The Effects of Dependence

During the late nineteenth century, most governments

in Latin America had been increasingly dominated by

NATIONALISM AND DICTATORSHIP IN LATIN AMERICA 609

landed or military elites, who controlled the mass of the

population---mostly impoverished peasants---by the bla-

tant use of military force. This trend toward authoritar-

ianism increased during the 1930s as domestic instability

caused by the effects of the Great Depression led to the

creation of dictatorships throughout the region. This

trend was especially evident in Argentina and Brazil

and to a lesser degree in Mexico---three countries that

together possessed more than half

of the land and wealth of Latin

America.

Argentina The political domi-

nation of Argentina by an elite

minority often had disastrous ef-

fects. The Argentine government,

controlled by landowners who had

benefited from the export of beef

and wheat, was slow to recognize

the growing importance of estab-

lishing a local industrial base. In

1916, Hip

olito Irigoyen (1852--

1933), head of the Radical Party,

was elected president on a pro-

gram to improve conditions for

the middle and lower classes. Little

was achieved, however, as the

party became increasingly corrupt

and drew closer to the large

landowners. In 1930, the army

overthrew Irigoyen’s government

and reestablished the power of the

landed class. But their efforts to

return to the previous export

economy and suppress the grow-

ing influence of the labor unions

failed.

Brazil Brazil followed a similar

path. In 1889, the army over-

threw the Brazilian monarchy,

installed by Por tugal years before,

and established a republic. But

it was dominated by landed

elites, many of whom had grown

wealthy through their ownership

of coffee plantations. By 1900,

three-quarters of the world’s

coffee was grown in Brazil. As in

Argentina, the r uling oligarchy

ignored the impor tance of es-

tablishing an urban industrial

base. When the Great Depression

ravaged profits from coffee exports, a wealthy rancher,

Get

ulio Vargas (1883--1954), seized power and ruled the

country as p resident from 1930 to 1945. At first, Vargas

sought to appeas e worker s by declaring an eight-hour

workday and a minimum wage, but, influenced by the

ap parent success of fascist regimes in Europe, he ruled

by increasing ly autocratic means and relied on a police

force that used torture to silence his opponents.

South

Atlantic

Ocean

South

Pacific

Ocean

North

Atlantic

Ocean

C

a

r

i

b

b

e

a

n

Sea

Rio de

Janeiro

Falkland

Islands (U.K.)

South Georgia

Island (U.K.)

Buenos

Aires

Santiago

Montevideo

Quito

Bogotá

Caracas

Lima

Asunción

La Paz

BRAZIL

BOLIVIA

PERU

COLOMBIA

GUATEMALA

EL SALVADOR

PANAMA

COSTA

RICA

NICARAGUA

HONDURAS

BRITISH HONDURAS

MEXICO

ECUADOR

VENEZUELA

PARAGUAY

CHILE

ARGENTINA

URUGUAY

FRENCH

GUIANA

BRITISH

GUIANA

DUTCH

GUIANA

0 500 1,000 Miles

0 500 1,000 1,500 Kilometers

MAP 24.2 Latin Ame rica in the First Half of the Twentieth Centu ry. Shown here

are the boundaries dividing the countries of Latin America after the independence

movements of the nineteenth century.

Q

Which areas remained under European rule?

610 CHAPTER 24 NATIONALISM, REVOLUTION, AND DICTATORSHIP

His industrial policy was relatively enlightened, how-

ever, and by the end of World War II, Brazil had become

Latin America’s major industrial power. In 1945, the

army, fearing that Vargas might prolong his power il-

legally after calling for new elections, forced him to

resign.

Mexico Mexico, in the early years of the new century,

was i n a stat e of turbulence. Under the rule of dictator

Porfirio D

ıaz (see Chapter 20), the real wages of the

working cla ss had declined. Moreover, 95 percent of t he

rural population owned no land, and about a thousand

families ruled almost all of Mexico. When a liberal

landowner, Francis co Madero, forced D

ıaz from power

in 1910, he opened the door to a wider revolution.

Madero’s ineffectiveness triggered a demand for agrar-

ian reform led by Emiliano Zapata (1879--1919), who

arousedthemassesoflandlesspeasantsinsouthern

Mexico and began to seize the haciendas of wealthy

landholders.

For the next several years, Zapata and rebel leader

Pancho Villa (1878--1923), who operated in the northern

state of Chihuahua, became an important political force

in the country by publicly advocating efforts to redress

the economic grievances of the poor. But neither had a

broad grasp of the challenges facing the country, and

power eventually gravitated to a more moderate group of

reformists around the Constitutionalist Party. The latter

were intent on breaking the power of the great landed

families and U.S. corporations, but without engaging in

radical land reform or the nationalization of property.

After a bloody conflict that cost the lives of thousands, the

moderates consolidated power, and in 1917, they pro-

mulgated a new constitution that established a strong

presidency, initiated land reform policies, established

limits on foreign investment, and set an agenda for social

welfare programs.

In 1920, Constitutionalist leader Alvaro O breg

on

assumed the presidency and began t o ca rry out his re-

form program. But real change did not take place until

the presidency of General L

azaro C

ardenas (1895--1970)

in 1934. C

ardenas won wide popularity wi th the peas-

ants by ordering the redistribution of 44 million acres of

land controlled by landed elites. He also sei zed control

of the oil industr y, which had hitherto been dominated

by major U.S. oil companies. Alluding to the Good

Neighbor policy, President Roosevel t refused to inte r-

vene, and eventually Mexico agreed to compensate U.S.

oil companies for their lost property. It then set up

PEMEX, a governmental organization, to run the oil

industry.

Latin American Culture

The first half of the twentieth century witnessed a dra-

matic increase in literary activity in Latin America, a re-

sult in part of its ambivalent relationship with Europe and

the United States. Many authors, while experimenting

with imported modernist styles, felt compelled to pro-

claim Latin America’s unique identity through the

adoption of native themes and social issues. In The

Underdogs (1915), for example, Mariano Azuela (1873--

1952) presented a sympathetic but not uncritical portrait

of the Mexican Revolution as his country entered an era

of unsettling change.

In their determination to commend Latin America’s

distinctive characteristics, some writers extolled the

promise of the region’s vast virgin lands and the di-

versity of its peoples. I n Don Segundo Sombra, published

in 1926, Ricardo Guiraldes (1886--1927) celebrated the

life of the ideal gaucho (cowboy ), defining Argentina’s

hope and strength through the enlig htened manage-

ment of its fertile earth. Likewise, in Dona B arb ara,

R

omulo Gallegos (1884--1969) w rote in a similar vein

about his native Venezuela. Other authors pu rsued

the theme of solitude and detachment, a product of

the region’s physical separation from the rest of the

world.

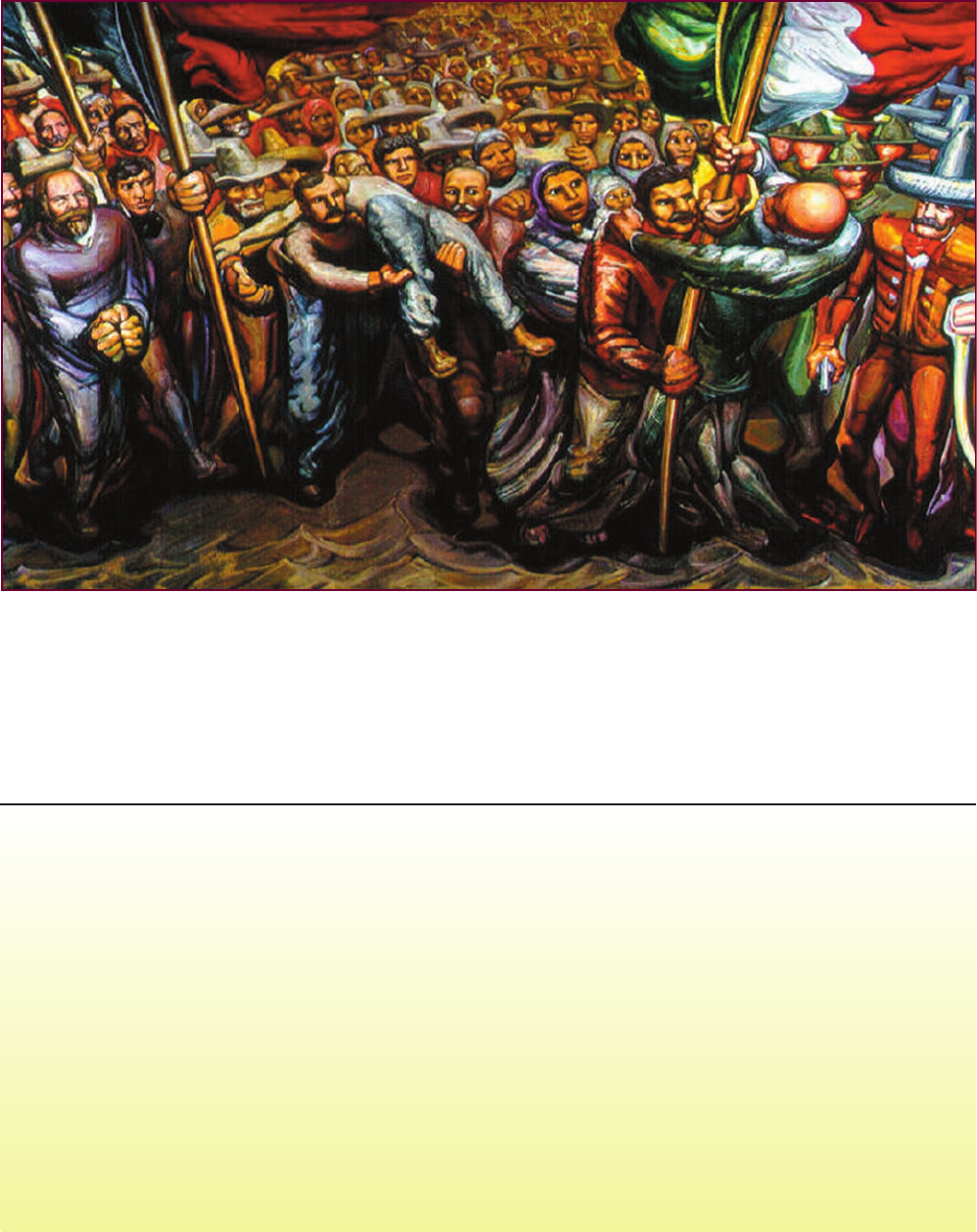

Latin American artists followed their literar y

counterparts in joining the Modernist movement in

Euro pe, yet they too were eager to promote the emer-

gence of a new regional and national essence. In

Mexico, where the government provided financial

support for painting murals on public buildings, the

artist Diego Rivera (1886--1957) began to produce a

monumental st yle of mural ar t that served two pur-

poses: to illustrate the national past by por traying

Aztec legends and folk customs and to popularize a

political message in favor of realizing the social goals of

the Mexican Revolution. His w ife, Frida Kahlo (1907--

1954), incorporated Surrealist whimsy in her own

paintings, many of which were por traits of herself and

her family.

CHRONOLOGY

Latin America Between the Wars

Hip

olito Irigoyen becomes president

of Argentina

1916

Argentinian military overthrows Irigoyen 1930

Rule of Get

ulio Vargas in Brazil 1930--1945

Presidency of L

azaro C

ardenas in Mexico 1934--1940

Beginning of Good Neighbor policy 1935

N

ATIONALISM AND DICTATORSHIP IN LATIN AMERICA 611

Struggle for the Bann er. Like Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974) adorned public buildings

with large murals that celebrated the Mexican Revolution and the workers’ and peasants’ struggle for freedom.

Beginning in the 1930s, Siqueiros expressed sympathy for the exploited and downtrodden peoples of Mexico in

dramatic frescoes such as this one. He painted similar murals in Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil and was once

expelled from the United States, where his political art and views were considered too radical.

CONCLUSION

THE TURMOIL BROUGHT about by World War I not only

resulted in the destruction of several of the major Western empires

and a redrawing of the map of Europe but also opened the door to

political and social upheavals elsewhere in the world. In the Middle

East, the decline and fall of the Ottoman Empire led to the creation

of the secular republic of Turkey. The state of Saudi Arabia emerged

in the Arabian peninsula, and Palestine became a source of tension

between newly arrived Jewish immigrants and longtime Muslim

residents.

Other parts of Asia and Africa also witnessed the rise of

movements for national independence. In Africa, these movements

were spearheaded by native leaders educated in Europe or the

United States. In India, Gandhi and his campaign of civil

disobedience played a crucial role in his country’s bid to be free of

British rule. Communist movements also began to emerge in Asian

societies as radical elements sought new methods of bringing about

the overthrow of Western imperialism. Japan continued to follow its

own path to modernization, which, although successful from an

economic point of view, took a menacing turn during the 1930s.

Between 1919 and 1939, China experienced a dramatic

struggle to establish a modern nation. Two dynamic political

organizations---the Nationalists and the Communists---competed for

legitimacy as the rightful heirs of the old order. At first, they formed

an alliance in an effort to defeat their common adversaries, but

cooperation ultimately turned to conflict. The Nationalists under

Chiang Kai-shek emerged supreme, but Chiang found it difficult to

control the remnants of the warlord regime in China, while the

Great Depression undermined his efforts to build an industrial

nation.

During the interwar years, the nations of Latin America faced

severe economic problems because of their dependence on exports.

Increasing U.S. investments in Latin America contributed to

growing hostility toward the powerful neighbor to the north. The

Great Depression forced the region to begin developing new

c

2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/SOMAAP, Mexico City//Digital image

c

Schalwijk/Art Resource, NY

612 CHAPTER 24 NATIONALISM, REVOLUTION, AND DICTATORSHIP

SUGGESTED READING

Nationalism The classic study of nationalism in the non-

Western world is R. Emerson, From Empire to Nation (Boston,

1960). For a more recent approach, see B. Anderson, Imagined

Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism

(London, 1983). On nationalism in India, see S. Wolpert, Congress

and Indian Nationalism: The Pre-Independence Phase (New York,

1988). Also see P. Chatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments:

Colonial and Postcolonial Histories (Princeton, N.J., 1993), and

E. Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (Ithaca, N.Y., 1994).

Gandhi There have been a number of studies of Mahatma

Gandhi and his ideas. See, for example, S. Wolpert, Gandhi’s

Passion: The Life and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi (Oxford, 1999),

and D. Dalton, Mahatma Gandhi: Nonviolent Power in Action

(New York, 1995). For a study of Nehru, see J. M. Brown, Nehru

(New York, 2000).

Middle East For a general survey of events in the Middle East

in the interwar era, see E. Bogle, The Modern Middle East: From

Imperialism to Freedom (Upper Saddle River, N.J., 1996). For more

specialized studies, see I. Gershoni et al., Egypt, Islam, and the

TIMELINE

1920

1925 1930 1935 1940

Middle

East

Asia

Latin

America

Reza Khan seizes power in Iran

Formation of Chinese Communist Party

Formation of Comintern

American Good Neighbor policy beginsVargas takes power in Brazil

Northern Expedition

in China

Creation of Nanjing Republic

The Long March

Creation of Turkey under Atatürk

Ibn Saud establishes Saudi Arabia

May Fourth Movement

New constitution in Mexico

Gandhi’s march to the sea

Army seizes power in Argentina

Rise of militant

government in

Japan

British mandate in Iraq Discovery of oil

in Iraq

industries, but it also led to the rise of authoritarian governments,

some of them modeled after the fascist regimes of Italy and

Germany.

By demolishing the remnants of their old civilization on

the battlefields of World War I, Europeans had inadvertently

encouraged the subject peoples of thei r vast colonial empires

to begi n their own movements for national independence.

The process was by no means completed in the two decades

following the Treaty of Versailles, but the bonds of imperial rule

had been severely strained. Once Europeans began to weaken

themselves in the even more destructive conflict of World War II,

the hopes of African and Asian peoples for nationa l independence

and freedom could at last be realized. It is to that devastating world

conflict that we now turn.

CONCLUSION 613

Arabs: The Search for Egyptian Nationhood (Oxford, 1993), and

W. Laqueur, A History of Zionism: From the French Revolution to

the Establishment of the State of Israel (New York, 1996). The role

of Atat

€

urk is examined in A. Mango, Atat

€

urk: The Biography of the

Founder of Modern Turkey (New York, 2000). The Palestinian issue

is dealt with in B. Morris, Righteous Victims: The Palestinian

Conflict, 1880--2000 (New York, 2001). On the founding of Iraq, see

S. Mackey, The Reckoning: Iraq and the Legacy of Saddam Hussein

(New York, 2002). Nascent nationalist movements in Africa are

discussed in R. Collins, Historical Problems of Imperial Africa

(Princeton, N.J., 1994). For a penetrating account of the fall of the

Ottoman Empire and its consequences for the postwar era, see

D. Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman

Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East

(New York, 2001).

China On the early Chinese republic, a good study is

J . Fitzgerald, A wakening China: Politics, Culture, and Class in the

Nationalist Revolution (Stanford, Calif., 1996). The rise of the Chinese

Communist Party is discussed in A. Dirlik, The Origins of Chinese

Communism (Oxford, 1989). Also see J. Fenby, Chiang Kai-shek:

China ’s Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost (New York, 2003).

Latin America For an overview of Latin American history in

the interwar period, see E. Williamson, The Penguin History of

Latin America (Harmondsworth, England, 1992). Also see

J. Franco, The Modern Culture of Latin America: Society and

the Artist (Harmondsworth, England, 1970).

Women For a general introduction to the women’s movement

during this era, consult C. Johnson-Odim and M. Strobel, eds.,

Restoring Women to History (Bloomington, Ind., 1999). For

collections of essays concerning African women, see C. Robertson

and I. Berger, Women and Class in Africa (New York, 1986), and

S. Stichter and J. I. Parparti, eds., Patriarchy and Class: African

Women in the Home and Workforce (Boulder, Colo., 1988). To

follow the women’s movement in India, see S. Tharu and K. Lalita,

Women Writing in India, vol. 2 (New York, 1993). For Japan,

see S. Sievers, Flowers in Salt: The Beginnings of Feminist

Consciousness in Modern Japan (Stanford, Calif., 1983).

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

614 CHAPTER 24 NATIONALISM, REVOLUTION, AND DICTATORSHIP

615