Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

course they are a great deal more dangerous because they

are the combustible material for which only a single spark

is needed to burst into flame.’’

5

On March 8, a day cele-

brated since 1910 as International Women’s Day, about

10,000 women marched through Petrograd demanding

‘‘peace and bread.’’ Soon the women were joined by other

workers, and together they called for a general strike that

succeeded in shutting down all the factories in the city on

March 10. Nicholas ordered his troops to disperse the

crowds by shooting them if necessary, but large numbers

of the soldiers soon joined the demonstrators. The Duma

(legislature), which the tsar had tried to dissolve, met

anyway and on March 12 declared that it was assuming

governmental responsibility. It established a provisional

government on March 15; the tsar abdicated the same day.

The Provisional Government, which came to be led

in July by Alexander Kerensky, decided to carry on the

war to preserve Russia’s honor---a major blunder because

it satisfied neither the workers nor the peasants, who

wanted more than anything an end to the war. The

Provisional Government also faced another authority, the

soviets, or councils of workers’ and soldiers’ deputies.

The soviet of Petrograd had been formed in March 1917;

at the same time, soviets sprang up spontaneously in

army units, factory towns, and rural areas. The soviets

represented the more radical interests of the lower classes

and were largely composed of socialists of various kinds.

One group---the Bolsheviks---came to play a crucial role.

Lenin and the Bolshevik Revolution The Bolsheviks

were a small faction of Russian Social Democrats who had

come under the leadership of Vladimir Ulianov, known to

the world as V. I. Lenin (1870--1924). Under Lenin’s di-

rection, the Bolsheviks became a party dedicated to violent

revolution. He believed that only a revolution could

destroy the capitalist system and that a ‘‘vanguard’’ of

activists must form a small party of well-disciplined pro-

fessional revolutionaries to accomplish this task. Between

1900 and 1917, Lenin spent most of his time in exile in

Switzerland. When the Provisional Government was set

up in March 1917, he believed that an opportunity for the

Bolsheviks to seize power had come. A month later, with

the connivance of the German High Command, which

hoped to create disorder in Russia, Lenin was shipped to

Russia in a ‘‘sealed train’’ by way of Finland.

Lenin believed that the Bolsheviks must work toward

gaining control of the soviets of soldiers, workers, and

peasants and then use them to overthrow the Provisional

Government. At the same time, the Bolsheviks sought

mass support through promises geared to the needs of the

people: an end to the war, redistribution of all land to the

peasants, the transfer of factories and industries from

capitalists to committees of workers, and the relegation of

government power from the Provisional Government to

the soviets. Three simple slogans summed up the Bol-

shevik program: ‘‘Peace, Land, Bread,’’ ‘‘Worker Control

of Production,’’ and ‘‘All Power to the Soviets.’’

By the end of October, the Bolsheviks had achieved a

slight majority in the Petrograd and Moscow soviets. The

number of party members had also grown from 50,000 to

240,000. With Leon Trotsky (1877--1940), a fervid revo-

lutionary, as chairman of the Petrograd soviet, Lenin and

the Bolsheviks were in a position to seize power in the

name of the soviets. During the night of November 6,

pro-soviet and pro-Bolshevik forces took control of Pet-

rograd. The Provisional Government quickly collapsed,

with little bloodshed. The following night, the All-Russian

Congress of Soviets, representing local soviets from all

over the country, affirmed the transfer of power. At the

second session, on the night of November 8, Lenin an-

nounced the new Soviet government, the Council of

People’s Commissars, with himself as its head.

But the Bolsheviks, soon renamed the Communists,

still faced enormous obstacles. For one thing, Lenin had

promised peace, and that, he realized, was not an easy

promise to fulfill because of the humiliating losses of

Russian territory that it would entail. There was no real

choice, however. On March 3, 1918, Lenin signed the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany and gave up eastern

Poland, Ukraine, and the Baltic provinces. He had

promised peace to the Russian people; but real peace did

not come, for the country soon sank into civil war.

Civil War There was great opposition to the new

Communist regime, not only from groups loyal to the

tsar but also from bourgeois and aristocratic liberals and

anti-Leninist socialists. In addition, thousands of Allied

troops were eventually sent to different parts of Russia.

Between 1918 and 1921, the Communist (Red) Army

was forced to fight on many fronts. The first serious

threat to the Communists came from Siberia, where a

White (anti-Communist) force attacked westward and

advanced almost to the Volga River. Attacks also came

from the Ukrainians in the southwest and from the Baltic

regions. In mid-1919, White forces swept through

Ukraine and advanced almost to Moscow before being

pushed back. By 1920, the major White forces had been

defeated, and Ukraine had been retaken. The next year,

the Communist regime regained control over the

independent nationalist governments in the Caucasus:

Georgia, Russian Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

How had Lenin and the Bolsheviks triumphed over

what seemed at one time to be overwhelming forces? For

one thing, the Red Army became a well-disciplined

fighting force, largely due to the organizational genius of

Leon Trotsky. As commissar of war, Trotsky reinstated the

576 CHAPTER 23 THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY CRISIS: WAR AND REVOLUTION

draft and insisted on rigid discipline; soldiers who de-

serted or refused to obey orders were summarily executed.

In addition, the disunity of the anti-Communist

forces seriously weakened the efforts of the Whites. Po-

litical differences created distrust among the Whites and

prevented them from cooperating effectively. It was dif-

ficult enough to achieve military cooperation; political

differences made it virtually impossible. The lack of a

common goal on the part of the Whites was in sharp

contrast to the single-minded sense of purpose of the

Communists.

The Communists also succeeded in translating their

revolutionary faith into practical instruments of power . A

policy of ‘‘war communism,’’ for example, was used to

ensure regular supplies for the Red Army. ‘‘War com-

munism’’ included the nationalization of banks and most

industries, the forcible requisition of grain from peasants,

and the centralization of state power under Bolshevik

control. Another Bolshevik instrument was ‘‘revolutionary

terror.’’ A new Red secret police---known as the Cheka---

instituted the Red Terror, aimed at nothing less than the

destruction of all who opposed the new regime.

Finally, the intervention of foreign armies enabled the

Communists to appeal to the powerful force of Russian

patriotism. Appalled by the takeover of power in Russia

by the radical Communists, the Allied Powers intervened.

At one point, more than 100,000 foreign troops---mostly

Japanese, British, American, and French---were stationed

on Russian soil. This intervention by the Allies enabled

the Communist government to appeal to patriotic

Russians to fight the attempts of foreigners to control

their country.

By 1921, the Communists were in control of Russia.

In the course of the civil war, the Communist regime had

also transformed Russia into a bureaucratically central-

ized state dominated by a single party. It was also a state

that was largely hostile to the Allied Powers that had

sought to assist the Communists’ enemies in the civil war.

The Last Year of the War

For Germany, the withdrawal of the Russians in March

1918 offered renewed hope for a favorable end to the war.

The victory over Russia persuaded Erich von Ludendorff

(1865--1937), who guided German military operations,

and most German leaders to make one final military

gamble---a grand offensive in the west to break the military

stalemate. The German attack was launched in March and

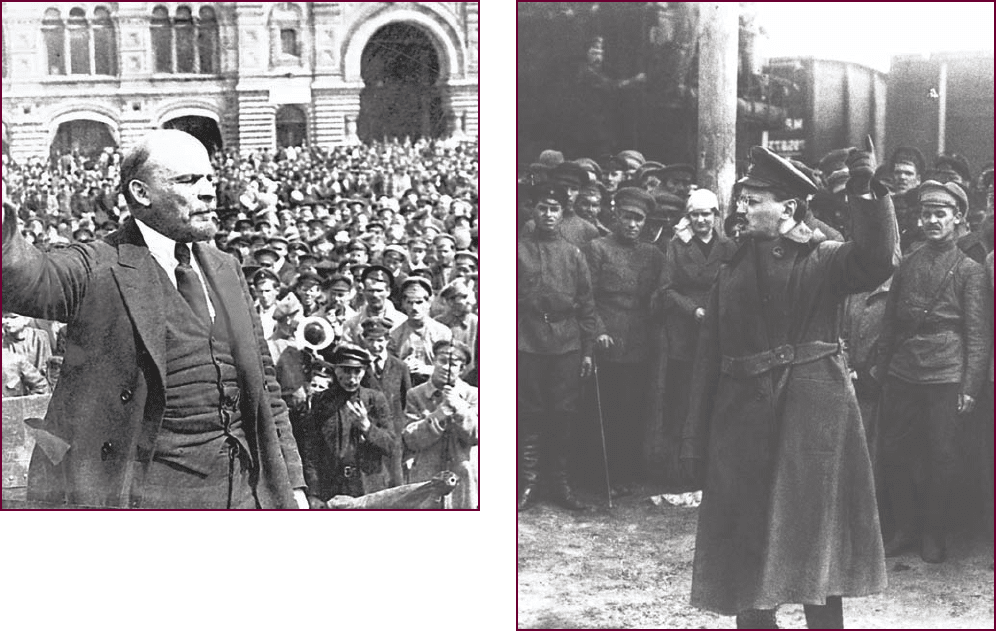

Lenin and Trotsky. Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky were important

figures in the Bolsheviks’ successful seizure of power in Russia. On the left,

Lenin is seen addressing a rally in Moscow in 1917. On the right, Trotsky,

who became commissar of war in the new regime, is shown haranguing

his troops.

c

Keystone/Getty Images

c

Underwood & Underwood/CORBIS

CRI SIS IN RUSSIA A ND THE END OF THE WAR 577

lasted into July, but an Allied counterattack, supported by

the arrival of 140,000 fresh American troops, defeated the

Germans at the Second Battle of the Marne on July 18.

Ludendorff’s gamble had failed.

On September 29, 1918, General Ludendorff in-

formed German leaders that the war was lost and insisted

that the government sue for peace at once. When German

officials discovered, however, that the Allies were un-

willing to make peace with the autocratic imperial gov-

ernment, reforms were instituted to create a liberal

government. Meanwhile, popular demonstrations broke

out throughout Germany. William II capitulated to

public pressure and abdicated on November 9, and the

Socialists under Friedrich Ebert (1871--1925) announced

the establishment of a republic. Two days later, on

November 11, 1918, the new German government agreed

to an armistice. The war was over.

The Casualties of the War World War I devastated

European civilization. Between 8 and 9 million soldiers

died on the battlefields; another 22 million were

wounded. Many of the survivors died later from war in-

juries or lived on without arms or legs or with other forms

of mutilation. The birthrate in many European countries

declined noticeably as a result of the death or maiming of

so many young men. World War I also created a lost

generation of war veterans who had become accustomed

to violence and who would later band together in support

of Mussolini and Hitler in their bids for power.

Nor did the killing affect only soldiers. Untold

numbers of civilians died from war injuries or starvation.

In 1915, after an Armenian uprising against the Ottoman

government, the government retaliated with fury by kill-

ing Armenian men and expelling women and children.

Within seven months, 600,000 Armenians had been killed,

and 500,000 had been deported. Of the latter, 400,000 died

while marching through the deserts and swamps of Syria

and Mesopotamia. By September 1915, an estimated one

million Armenians were dead, the victims of genocide.

The Peace Settlement

In January 1919, the delegations of twenty-seven victo-

rious Allied nations gathered in Paris to conclude a final

settlement of the Great War. Over a period of years, the

reasons for fighting World War I had been transformed

from selfish national interests to idealistic principles. No

one expressed the latter better than the U.S. president

Woodrow Wilson (1856--1924). Wilson’s proposals for a

truly just and lasting peace included ‘‘open covenants of

peace, openly arrived at’’ instead of secret diplomacy; the

reduction of national armaments to a ‘‘point consistent

with domestic safety’’; and the self-determination of

people so that ‘‘all well-defined national aspirations shall

be accorded the utmost satisfaction.’’ As the spokesman

for a new world order based on democracy and inter-

national cooperation, Wilson was enthusiastically cheered

by many Europeans when he arrived in Europe for the

peace conference.

Wilson soon found, however, that more practical

motives guided other states at the Paris Peace Conference.

The secret treaties and agreements that had been made

before the war could not be totally ignored, even if they

did conflict with the principle of self-determination

enunciated by Wilson. National interests also complicated

the deliberations of the Paris Peace Conference. David

Lloyd George (1863--1945), prime minister of Great

Britain, had won a decisive electoral victory in December

1918 on a platform of making the Germans pay for this

dreadful war.

France’s approach to peace was primarily determined

by considerations of national security. To Georges

Clemenceau (1841--1929), the feisty premier of France

who had led his country to victory, the French people had

borne the brunt of German aggression. They deserved

revenge and security against future German aggression.

The most importa nt decisions at the Paris Peace

Conf erence were made by Wilson, Clemenceau, and

Lloyd George. In the end, only compromise made it

possible to achieve a peace settlement. Wilson’s wish that

CHRONOL OGY

World War I

1914

Battle of Tannenberg August 26--30

First Battle of the Marne September 6--10

Battle of Masurian Lakes September 15

1915

Battle of Gallipoli begins April 25

Italy declares war on

Austria-Hungary

May 23

1916

Battle of Verdun February 21--December 18

1917

United States enters the war April 6

1918

Last German offensive March 21--July 18

Second Battle of the Marne July 18

Allied counteroffensive July 18--November 10

Armistice between Allies

and Germany

November 11

578 CHAPTER 23 THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY CRISIS: WAR AND REVOLUTION

the creation of an international peacekeeping organiza-

tion be the first order of business w as granted, and

already on January 25, 1919, the conference adopted the

principle of the Le ague of Nations. In return, Wilson

agreed to make compromises on territorial arrange-

ments to guara ntee the establishment of the League,

believing that a functioning League could later rectify

bad arr angements.

The Treaty of Versailles The final peace settlement

consisted of five separate treaties w ith the defeated

nations---Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, and

Turkey. The Treaty of Versailles with Germany, signed on

June 28, 1919, was by far the most important. The Ger-

mans considered it a harsh peace and were particularly

unhappy with Article 231, the so-called War Guilt Clause,

which declared Germany (and Austria) responsible for

starting the war and ordered Germany to pay reparations

for all the damage to which the Allied governments and

their people were subjected as a result of the war.

The military and territorial provisions of the treaty

also rankled Germans. Germany had to reduce its army to

100,000 men, cut back its navy, and eliminate its air force.

German territorial losses included the return of Alsace

and Lorraine to France and sections of Prussia to the new

Polish state (see Map 23.3). German land west and as far

GREAT

BRITAIN

NORWAY

SWEDEN

FINLAND

ESTONIA

LATVIA

LITHUANIA

POLAND

CZECHOSLOVAKIA

SPAIN

FRANCE

GERMANY

BELGIUM

NETH.

SWITZ.

ITALY

GREECE

ALBANIA

TURKEY

ROMANIA

BULGARIA

YUGOSLAVIA

AUSTRIA

HUNGARY

SOVIET

UNION

LUX.

DENMARK

SYRIA

IRAQ

IRAN

SAUDI ARABIA

TRANS-

JORDAN

PALESTINE

EGYPT

SERBIA

BESSARABIA

S. TYROL

ALSACE-

LORRAINE

SCHLESWIG

MEMEL

EAST

PRUSSIA

CORRIDOR

UPPER

SILESIA

GALICIA

TRANSYLVANIA

SAAR

DOBRUJA

RUTHENIA

MOLDAVIA

WALLACHIA

MONTENEGRO

CRIMEA

WHITE

RUSSIA

UKRAINE

London

Madrid

Paris

Amsterdam

Oslo

Stockholm

Berlin

Danzig

Bucharest

Rome

Fiume

Sofia

Petrograd

Prague

Warsaw

Athens

Copenhagen

Istanbul

Belgrade

Budapest

Vienna

Trieste

Cairo

Ankara

Baghdad

Suez

Canal

Kiev

Moscow

Reval

Helsinki

Riga

Kaunus

Brest-Litovsk

Lvov

Tirana

Munich

Weimar

C

a

s

p

i

a

n

S

e

a

V

o

l

g

a

R

.

M

e

d

i

t

e

r

r

a

n

e

a

n

S

e

a

Black Sea

Corsica

Sardinia

B

a

l

e

a

r

i

c

I

s

l

a

n

d

s

D

o

n

R.

D

n

i

e

p

e

r

R

.

North

Sea

E

u

p

h

r

a

t

e

s

R

.

M

E

S

O

P

O

T

A

M

I

A

T

R

A

N

S

C

A

U

C

A

S

I

A

A

Z

E

R

B

A

I

J

A

N

A

R

M

E

N

I

A

K

U

R

D

I

S

T

A

N

T

i

g

r

i

s

R

.

Crete

Sicily

Cyprus

B

a

l

t

i

c

S

e

a

E

b

r

o

R

.

A

d

r

i

a

t

i

c

S

e

a

P

o

R

.

0 300 600 Miles

0 300 600 900 Kilometers

By Russia

By Germany

By Ottoman Empire

By Bulgaria

By Austria-Hungary

Lost immediately after World War I

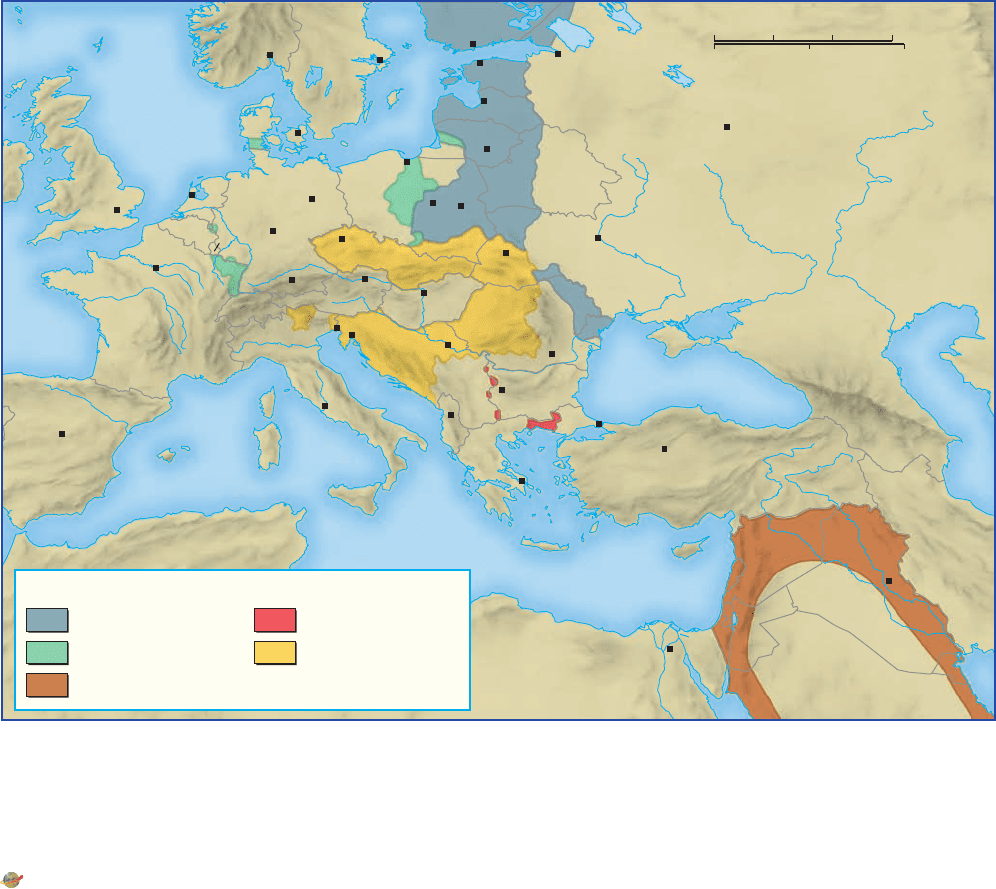

MAP 23.3 Te rritorial Changes in Europe and the Mi ddle Eas t Afte r Worl d War I. The

victorious Allies met in Paris to determine the shape and nature of postwar Europe. At the

urging of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, many nationalist aspirations of former imperial

subjects were realized with the creation of several new countries from the prewar territory

of Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire.

Q

What new c ountries emerged in Europe and the Middle East?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www .cengage.com/history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

CRI SIS IN RUSSIA A ND THE END OF THE WAR 579

as 30 miles east of the Rhine was established as a de-

militarized zone and stripped of all armaments or for-

tifications to serve as a barrier to any future German

military moves westward against France. Outraged by the

‘‘dictated peace,’’ the new German government com-

plained but accepted the treaty.

The Other Peace Treaties The separate peace treaties

made with the other Central Powers extensively redrew

the map of eastern Europe. Many of these changes merely

ratified what the war had already accomplished. Both the

German and Russian Empires lost considerable territory

in eastern Europe, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire

disappeared altogether. New nation-states emerged from

the lands of these three empires: Finland, Latvia, Estonia,

Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Hungary.

Territorial rearrangements were also made in the Balkans.

Serbia formed the nucleus of a new southern Slavic state,

called Yugoslavia, which combined Serbs, Croats, and

Slovenes.

Although the Paris Peace Conference was supposedly

guided by the principle of self-determination, the mix-

tures of peoples in eastern Europe made it impossible to

draw boundaries along neat ethnic lines. As a result of

compromises, v irtually every eastern European state was

left with a minorities problem that could lead to future

conflicts. Germans in Poland; Hungarians, Poles, and

Germans in Czechoslovakia; Hungarians in Romania; and

the combination of Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians,

and Albanians in Yugoslavia all became sources of later

conflict.

Yet another centuries-old empire, the Ottoman

Empire, was dismembered by the peace settlement after

the war. To gain Arab support against the Ottoman

Turks during t he war, the Western Allies had promised

to recognize the indepe ndence of

Arab states in the Middle Eastern

lands of the Ottoman Empire. But

the imperialist habits of Western

nations died hard. After the war,

France was given control of Leba-

non an d Syria, while Britain re-

ceived Iraq and Palestine. Officiall y,

both acquisitions were called man-

dates, a system whe reby a nation

officially administered a territory

on behalf of the Le ague of Nations.

The system of mandates could not

hide the f act that the principle of

national s elf-determination at the

Paris Peace Conference was largely

for Europeans.

An Uncertain Peace

Q

Focus Question: What problems did Europe and the

United States face in the 1920s?

Four years of devastating war had left many Europeans

with a profound sense of despair and disillusionment. The

Great War indicated to many people that something was

dreadfully wrong with Western values. In The Decline of

the West, the German writer Oswald Spengler (1880--1936)

reflected this disillusionment when he emphasized the

decadence of Western civilization and posited its collapse.

The Search for Security

The peace settlement at the end of World War I had tried

to fulfill the nineteenth-century dream of nationalism by

creating new boundaries and new states. From its in-

ception, however, this peace settlement had left nations

unhappy and only too eager to revise it.

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson had recognized that

the peace treaties contained unwise provisions that could

serve as new causes for conflicts, and he had placed many

of his hopes for the future in the League of Nations. The

League, however, was not particularly effective in main-

taining the peace. The failure of the United States to join

the League in a backlash of isolationist sentiment un-

dermined its effectiveness from the beginning. Moreover,

the League could use only economic sanctions to halt

aggression.

France’s search for security between 1919 and 1924

was founded primarily on a strict enforcement of the

Treaty of Versailles. This tough policy toward Germany

began with the issue of reparations, the payments that

the Germans were supposed to make to compensate for

war damage. In April 1921, the

Allied Reparations Commission

settled on a sum of 132 billion

marks ($33 billion) for German

reparations, payable in annual in-

stallments of 2.5 billion (gold)

marks. The new German republic

made its first payment in 1921, but

by the following year, facing finan-

cial problems, the German govern-

ment announced that it was unable

to pay more. Outraged, the French

government sent troops to occupy

the Ruhr valley, Germany’s chief

industrial and mining center. If the

Germans would not pay repa-

rations, the French would collect

C

a

C

C

s

p

s

i

a

n

S

e

a

M

e

M

M

d

i

t

e

r

r

a

r

r

n

e

a

n

S

e

a

Jer

Jer

Jer

Jer

er

r

Jer

Jer

Jer

Je

Jer

Jer

Jer

Jer

Jer

r

Jer

e

e

usa

usa

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

lemlem

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

u

u

uu

u

u

J

J

J

J

Jer

Jer

Jer

Jer

Jer

Jer

Jer

e

Jer

Jer

Jer

e

e

us

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

uu

u

u

u

u

J

J

J

J

J

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

le

e

e

Beirut

B

Cai

Ci

C

C

C

C

ro

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

Dam

am

am

am

am

a

m

am

asc

us

m

m

m

am

am

am

am

am

am

am

am

am

am

am

am

m

m

m

am

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

Con

Con

C

sta

sta

sta

sta

sta

sta

sta

sta

sta

sta

ta

sta

sta

ta

t

t

nti

nop

p

p

p

le

le

le

le

e

l

l

le

le

le

e

le

le

e

l

e

sta

sta

ta

sta

ta

ta

ta

sta

ta

p

p

p

p

le

le

le

le

le

le

le

le

le

e

Co

Co

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

(Instan

b

u

l

)

Ba

Ba

Ba

Bag

Ba

Bag

Ba

a

hdad

Ba

Ba

Ba

Bag

a

Ba

Ba

Ba

Ba

Ba

Ba

Ba

a

P

ERSIA

TURKEY

IRAQ

A

Q

SYRIA

A

TRA

RA

RA

RA

RA

RA

NS-

RA

RA

RA

RA

RA

R

RA

RA

R

R

RA

A

A

A

A

JOR

D

D

D

D

DAN

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

EGYPT

PAL

PAL

AL

EST

EST

EST

I

IN

INE

NE

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

LE

LEB

EB

EB

B

B

A

ANO

ANO

A

A

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

B

B

B

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

S

A

U

D

I

ARABIA

KUW

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

AIT

A

A

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

A

A

A

A

0 250 5

0

0

0

00

00

00

0

0

0

0

0

00

0

Mil

Mil

i

il

il

il

il

i

il

i

i

il

i

l

es

0

00

00

00

0

00

0

00

0

00

il

il

il

il

il

i

il

i

l

i

l

0

25

0

5

00

750

750

750

750

750

750

750

750

7

750

750

50

750

750

50

75

750

750

75

K

K

K

Ki

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

lom

ete

rs

0

7

7

7

7

7

7

7

7

7

750

750

750

750

50

750

750

7

750

7

50

0

0

0

0

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

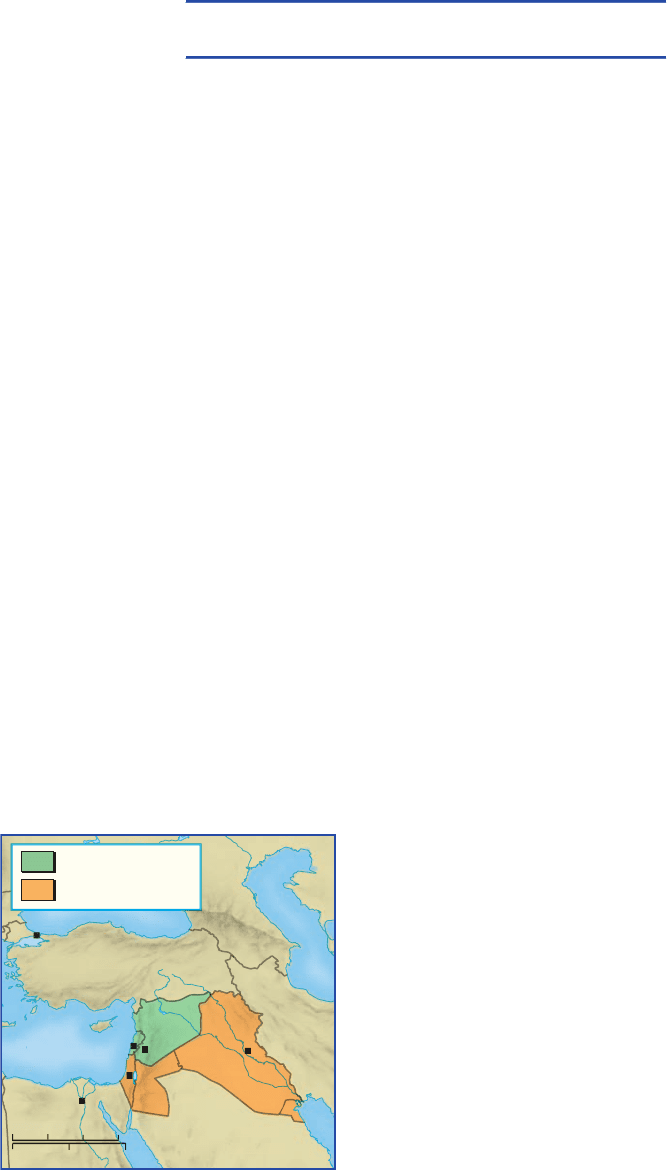

French mandates

British mandates

The Mi ddle East in 1919

580 CHAPTER 23 THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY CRISIS: WAR AND REVOLUTION

reparations in kind by operating and using the Ruhr

mines and factories.

Both Germany and France suffered from the French

occupation of the Ruhr. The German government

adopted a policy of passive resistance to French occupa-

tion that was largely financed by printing more paper

money. This only intensified the inflationary pressures

that had already begun in Germany by the end of the war.

The German mark became worthless, and economic di-

saster fueled political upheavals. All the nations, including

France, were happy to cooperate with the American

suggestion for a new conference of experts to reassess the

reparations problem.

In August 1924, an international commission pro-

duced a new plan for reparations. The Dawes Plan,

named after the American banker who chaired the

commission, reduced the reparations and stabilized Ger-

many’s payments on the basis of its ability to pay. The

Dawes Plan also granted an initial $200 million loan for

German recovery, which opened the door to heavy

American investments in Europe that helped create a new

era of European prosperity between 1924 and 1929.

With prosperity came a new age of European di-

plomacy. A spirit of cooperation was fostered by the

foreign ministers of Germany and France, Gustav Stre-

semann and Aristide Briand, who concluded the Treaty of

Locarno in 1925. This guaranteed Germany’s new western

borders with France and Belgium. Although Germany’s

new eastern borders with Poland were conspicuously

absent from the agreement, the Locarno

pact was viewed by many as the begin-

ning of a new era of European peace.

The spirit of Locarno was based on

little real substance, however. Germany

lacked the military p ower to alter its

western borders even if it wanted to. And

the issue of disarmament soon proved

that even the spirit of Locarno could not

bring nations to cut back on their

weapons. Germany, of course, had been

disarmed with the expectation that other

states would do likewise. N umerous dis-

armament confer enc es, however, failed to

achieve anything substantial as states

were unwilling to trust their security to

any one but their own military forces.

The Great Depression

Almost as devastating as the two world

wars in the first half of the twentieth

century was the economic collapse that

ravaged the world in the 1930s. Two events set the stage

for the Great Depression: a downturn in domestic eco-

nomic activities and an international financial crisis

precipitated by the collapse of the American stock market

in 1929.

Already in the mid-1920s, prices for agricultural

goods were beginning to decline rapidly due to over-

production of basic commodities, such as wheat. In ad-

dition to domestic economic troubles, much of the

European prosperity between 1924 and 1929 had been

built on American bank loans to Germany. The crash of

the U.S. stock market in October 1929 led panicky

American investors to withdraw many of their funds from

Germany and other European markets. The withdrawal of

funds seriously weakened the banks of Germany and

other central European states. By 1931, trade was slowing

down, industrialists were cutting back production, and

unemployment was increasing as the effects of interna-

tional bank failures had a devastating impact on domestic

economies.

Economic depression was by no means a new phe-

nomenon in European history, but the depth of the

economic downturn after 1929 fully justifies the label

Great Depression. During 1932, the worst year of the

depression, one British worker in four was unemployed;

in Germany, six million people, 40 percent of the labor

force, were out of work. The unemployed and homeless

filled the streets of the cities of the advanced industrial

countries (see the box on p. 582).

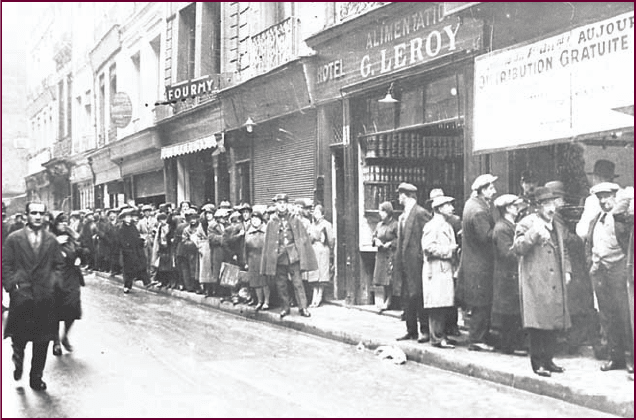

Great Dep ression: Bread Lines in Paris. The Great Depression devastated the European

economy and had serious political repercussions. Because of its more balanced economy, France

did not feel the effects of the depression as quickly as other European countries. By 1931, however,

even France was experiencing lines of unemployed people at free-food centers.

c

Roger Viollet/Getty Images

AN UNCERTAIN PEACE 581

Gove rnments seemed powerless to deal with the crisis.

The classic liberal remedy for depression, a deflationary

policy of balanced budgets, which invol ved cutting costs by

lowering wages and raising tariffs to exclude other c oun-

tries’ goods from home markets, only serv ed to worsen the

economic crisis and cause even greater mass discontent.

This in turn led to serious political repercussions. Increased

government activity in the economy was one reaction.

Another effect was a renewed interest in Marxist doctrines.

Hadn’t Marx predicted that capitalism would destroy itself

through overproduction? Communism took on new

popularity, especially with workers and intellectuals.

Finally, the Great Depression increased the attractiveness

of facile dictatorial solutions, especially from a new

movement known as fascism. Everywhere, democracy

seemed on the defensive in the 1930s.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION:UNEMPLOYED AND HOMELESS IN GERMANY

In 1932, Germany had six million unemployed

workers, many of them wandering aimlessly about

the country, begging for food and seeking shelter

in city lodging houses for the homeless. The Great

Depression was an important factor in the rise to power of

Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. This selection presents a description

of the unemployed homeless in 1932.

Heinrich Hauser, ‘‘With Germany’s Unempl oyed’’

An almost unbroken chain of homeless men extends the whole

length of the great Hamburg-Berlin highway. ... All the highways

in Germany over which I have traveled this year presented the

same aspect. ...

Most of the hikers paid no attention to me. They walked

separately or in small groups, with their eyes on the ground. And

they had the queer, stumbling gait of barefooted people, for their

shoes were slung over their shoulders. Some of them were guild

members---carpenters ...milkmen ...and bricklayers ...but they

were in a minority. Far more numerous were those whom one could

assign to no special profession or craft---unskilled young people, for

the most part, who had been unable to find a place for themselves

in any city or town in Germany, and who had never had a job and

never expected to have one. There was something else that had

never been seen before---whole families that had piled all their goods

into baby carriages and wheelbarrows that they were pushing along

as they plodded forward in dumb despair. It was a whole nation on

the march.

I saw them---and this was the strongest impression that the year

1932 left with me---I saw them, gathered into groups of fifty or a

hundred men, attacking fields of potatoes. I saw them digging up the

potatoes and throwing them into sacks while the farmer who owned

the field watched them in despair and the local policeman looked on

gloomily from the distance. I saw them staggering toward the lights

of the city as night fell, with their sacks on their backs. What did it

remind me of? Of the War, of the worst periods of starvation in

1917 and 1918, but even then people paid for the potatoes. ...

I saw that the individual can know what is happening only by

personal experience. I know what it is to be a tramp. I know what

cold and hunger are. ... But there are two things that I have only

recently experienced---begging and spending the night in a municipal

lodging house.

I entered the huge Berlin municipal lodging house in a north-

ern quarter of the city. ...

Distribution of spoons, distribution of enameled-ware bowls

with the words ‘‘Propert y of the City of Berlin’’ written on their

sides. Then the meal itself. A big kettle is carried in. Men with yel-

low smocks have brought it in, and men wi th yellow smocks ladle

out the food. These men, too, are homeless and they have been ex-

pressly picked by the establishment and given free food and lodging

and a little pocket money in exchange for their work about the

house.

Where have I seen this kind of food distribution before? In a

prison that I once helped to guard in the winter of 1919 during the

German civil war. There was the same hunger then, the same trem-

bling, anxious expectation of rations. Now the men are standing in

a long row, dressed in their plain nightshirts that reach to the

ground, and the noise of their shuffling feet is like the noise of big

wild animals walking up and down the stone floor of their cages be-

fore feeding time. The men lean far over the kettle so that the warm

steam from the food envelops them, and they hold out their bowls

as if begging and whisper to the attendant, ‘‘Give me a real helping.

Give me a little more.’’ A piece of bread is handed out with every

bowl.

My next recollection is sitting at table in another room on a

crowded bench that is like a seat in a fourth-class railway carriage.

Hundreds of hungry mouths make an enormous noise eating their

food. The men sit bent over their food like animals who feel that

someone is going to take it away from them. They hold their bowl

with their left arm partway around it, so that nobody can take it

away, and they also protect it with their other elbow and with their

head and mouth, while they move the spoon as fast as they can

between their mouth and the bowl.

Q

Why did Hauser compare the scene he describes from 1932

with the experiences of 1917 and 1918? Why did he compare

the hungry men to animals?

582 CHAPTER 23 THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY CRISIS: WAR AND REVOLUTION

The Democratic States

After World War I, Great Britain went through a period

of se rious economic difficulties. During the war, Britain

had lost many of the markets for its industrial products,

especially to the United States and Japan. The postwar

decli ne of such staple industries as coal, steel, and tex-

tiles led to a rise in unemploymen t, which reached the

two million mark in 1921. But Britain soon rebounded

and from 19 25 to 1929 experienced an era of renewed

prosperity.

By 1929, however, Britain faced the growing effects

of the Great Depression. A na tional government ( a co-

alition of Liberals and Conservatives) claimed credit for

bringing Britai n out of the worst stages of the depres-

sion, primarily by using the traditional policies of bal-

anced budgets and protective tariffs. British politicians

had largely ignored the new ideas of a Cambridge

economist, John Maynard Keynes (1883--1946), who

published his General Theory of Employment, Interest

and Money in 1936. He condemn ed the traditional view

that in a f ree economy, depressions should be left to

work themselves out. Keynes argued t hat unemployment

stemmed not from overproduction but from a decline in

demand and m aintained that demand could be in-

creased by putti ng people back to work building high-

ways and public structures, even if governments had to

go into debt to pay for these work s, a concept known as

defi cit spending.

After the defeat of Germany, France had become the

strongest power on the European continent, but between

1921 and 1926, no French government seemed capable of

solving the country’s financial problems. Like other

European countries, though, France did experience a

period of relative prosperity between 1926 and 1929.

Because it had a more balanced economy than other

nations, France did not begin to feel the full effects of

the Great Depression until 1932. Then economic in-

sta bility soon ha d political repercussions. During a

nin etee n-month period in 1932 and 1933, six different

cabinets were formed as France faced political chaos.

Finally, in June 1936, a coalition of leftist parties---

Communists, Socialists, and Radicals---formed a new

government, the Popular Front, but its po licies failed

to solve th e problems of the depression. By 1938, the

French were experiencing a serious decli ne of confi-

den ce in the ir political system.

After the imperial Germany of William II had come

to an end in 1918 with Germany’s defeat in World War I, a

German democratic state known as the Weimar Republic

was established. From its beginnings, the Weimar Re-

public was plagued by a series of problems. The republic

had no truly outstanding political leaders and faced se-

rious economic difficulties. Germany experienced run-

away inflation in 1922 and 1923; widows, orphans, the

retired elderly, army officers, teachers, civil servants, and

others who lived on fixed incomes all watched their

monthly stipends become worthless and their lifetime

savings disappear. Their economic losses increasingly

pushed the middle class to the rightist parties that were

hostile to the republic. To make matters worse, after a

period of prosperity from 1924 to 1929, Germany faced

the Great Depression. Unemployment increased to

3 million in March 1930 and 4.4 million by December of

the same year. The depression paved the way for the rise

of extremist parties .

After Germany, no Western nation was more af-

fected by the Great Depression than the United States.

By 1932, U.S. industrial production fell to 50 percent of

what it had been in 1929. By 1933, there were 15 mil-

lion unemployed. Under these circumstances, the

Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882--1945) was

able to win a landslide electoral v ictor y in 1932. He and

his advisers pursued a policy of active government in-

tervention in the economy that came to be known as

the New Deal. Economic intervention included a

stepped-up program of public works, such as the

Works Progress Administration (WPA), which was es-

tablished in 1935 and employed between two and three

million people who worked at building bridges, roads,

post offices, and airports. In 1935, the Social Security

Act created a system of old-age pensions and unem-

ployment insurance.

The New Deal provided some social reform mea-

sures, but it did not solve the unemployment problems of

the Great Depression. In May 1937, during what was

considered a period of full recovery, American unem-

ployment still stood at seven million.

Socialism in Soviet Russia

The civil war in Russia had taken an enormous toll of life.

Lenin had pursued a policy of war communism, but once

the war was over, peasants began to sabotage the program

by hoarding food. Added to this problem was drought,

which caused a famine between 1920 and 1922 that

claimed as many as five million lives. Industrial collapse

paralleled the agricultural disaster. By 1921, industrial

output was only 20 percent of its 1913 levels. Russia was

exhausted. A peasant banner proclaimed, ‘‘Down with

Lenin and horseflesh, Bring back the Tsar and pork.’’ As

Leon Trotsky said, ‘‘The country, and the government

with it, were at the very edge of the abyss.’’

6

AN UNCERTAIN PEACE 583

In March 1921, Lenin pulled Russia back from the

abyss by adopting his New Economic Policy (NEP), a

modified version of the old capitalist system. Peasants

were now allowed to sell their produce openly. Retail

stores as well as small industries that employed fewer than

twenty employees could now operate under private

ownership, although heavy industry, banking, and mines

remained in the hands of the government.

In 1922, Lenin and the Communists formally created

a new state called the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,

known as the USSR by its initials or the Soviet Union by

its shortened form. Already by that year, a revived market

and a good harvest had brought the famine to an end;

Soviet agricultural production climbed to 75 percent of

its prewar level.

Lenin’s death in 1924 inaugurated a struggle for

power among the seven members of the Politburo, the

institution that had become the leading organ of the

party. The Politburo was divided over the future direction

of Soviet Russia. The Left, led by Leon Trotsky, wanted to

end the NEP, launch Russia on the path of rapid indus-

trialization, and spread the revolution abroad. Another

group in the Politburo, called the Right, rejected the cause

of world revolution and wanted instead to concentrate on

constructing a socialist state in Russia. This group also

favored a continuation of Lenin’s NEP.

These ideological divisions were underscored by an

intense personal rivalry between Leon Trotsky and Joseph

Stalin (1879--1953). In 1924, Trotsky held the post of

commissar of war and was the leading spokesman for the

Left in the Politburo. Stalin was content to hold the dull

bureaucratic job of party general secretary while other

Politburo members held party positions that enabled them

to display their brilliant oratorical abilities. Stalin was

skillful in avoiding allegiance to either the Left or Right

factions in the Politburo. He was also a good organizer (his

fellow Bolsheviks called him ‘‘Comrade Index-Card’’) and

used his post as party general secretary to gain complete

control of the Communist Party. Trotsky was expelled

from the party in 1927. By 1929, Stalin had succeeded in

eliminating the Bolsheviks of the revolutionary era from

the Politburo and establishing a dictatorship.

In Pursuit of a New Reality:

Cultural and Intellectual Trends

Q

Focus Question: How did the cultural and intellectual

trends of the interwar years reflect the crises of those

years as well as the experience of World War I?

In the aftermath of the Great War, as they tried to

rebuild their l ives, Europeans wondered what ha d

gone w rong w ith Western civilization. For many, their

faith in progress had been shattered. The Great De-

pression on ly added to the despair lingering from

World War I.

The political and economic uncertainties were

paralleled by social innovations. The Great War had

served to break dow n many traditional middle-class

attitudes, especially toward sexuality. In the 1920s,

women’s physical appearance changed dramatically.

Short skirts, short hair, the use of cosmetics that were

once thought to be the preserve of prostitutes, and the

new practice of suntanning gave women a new image.

This change in physical appearance, which stressed

more exposure of a woman’s body, was also accompa-

nied by frank discussions of sexual matters. In 1926, the

Dutch physician Theodor van de Velde published Ideal

Marriage: Its Physiology and Technique, which became

an international best-seller. Van de Velde described fe-

male and male anatomy and glorified sexual pleasure in

marriage.

Nightmares and New Visions

Uncertainty also per vaded the cultural and intellectual

achievements of the interwar years. Postwar ar tistic

trends were largely a working out of the implications of

prewar developments. Abstract painting, for example,

became ever more popular (see the comparative essay

‘‘A Revolution in the A rts’’ on p. 585). In addition,

prewar fascination w ith the absurd and the unconscious

content of the mind seemed even more appropriate

after the nig htmare landscapes of World War I battle-

fronts. This gave rise to both the Dada movement and

Surrealism.

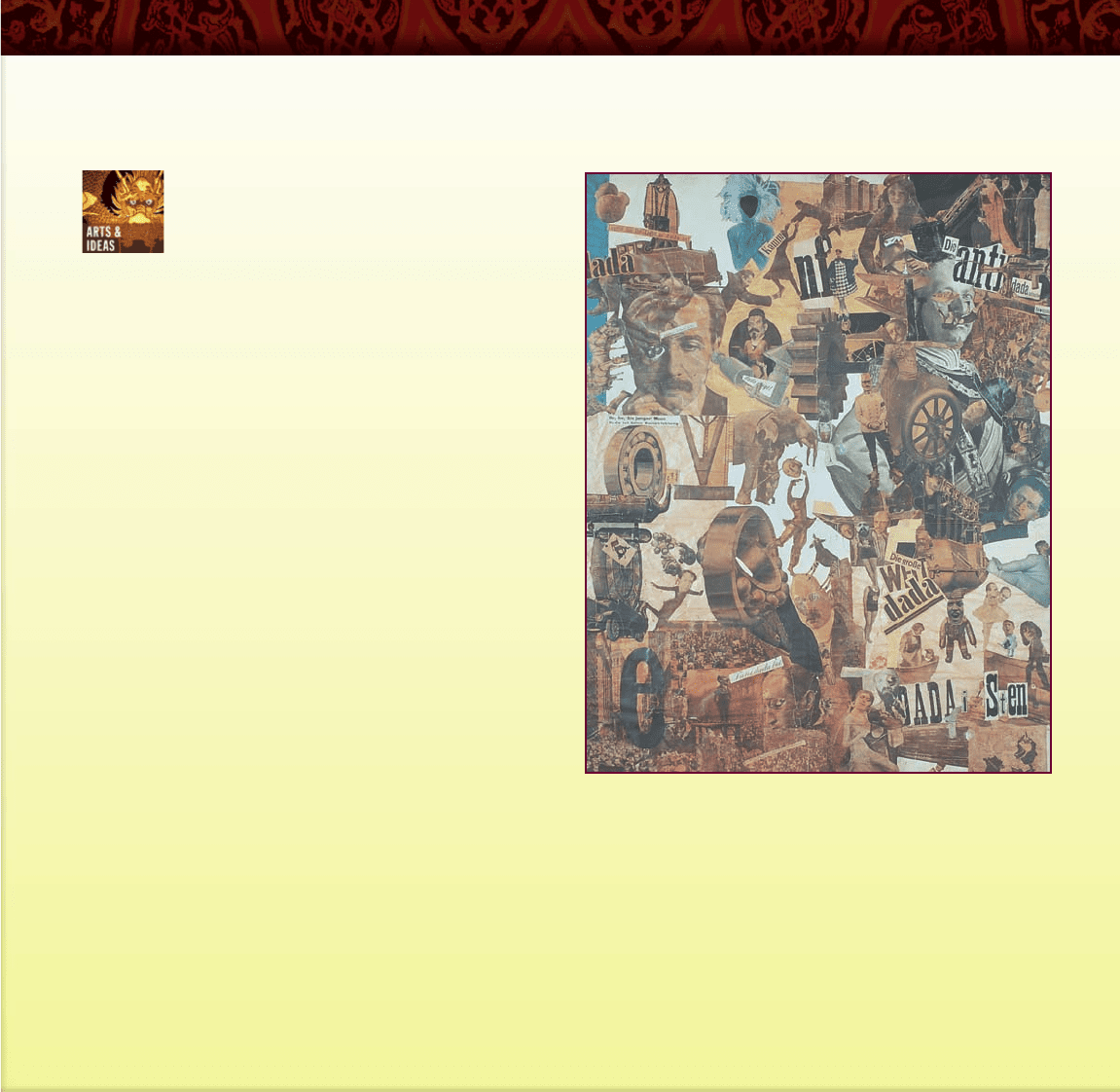

Dadaism enshrined the purposelessness of life; re-

volted by the insanity of life, the Dadaists tried to give it

expression by creating ‘‘anti-art.’’ The 1918 Berlin Dada

Manifesto maintained that ‘‘Dada is the international

expression of our times, the great rebellion of artistic

movements.’’ Many Dadaists assembled pieces of junk

(wire, string, rags, scraps of newspaper, nails, washers)

into collages, believing that they were transforming the

refuse of their culture into art. In the hands of Hannah

Ho

¨

ch (1889--1978), Dada became an instrument to

comment on women’s roles in the new mass culture (see

the illustration on p. 585).

Perhaps more important as an ar tistic movement

was Surrealism, which soug ht a reality beyond the

material, sensible world and found it in the world of the

unconscious through the por trayal of fantasies, dreams,

or nightmares. The Spaniard Salvador Dal

ı (1904--

1989) became the high priest of Surrealism and in his

584 CHAPTER 23 THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY CRISIS: WAR AND REVOLUTION

mature phase became a master of representational

Surrealism. Dal

ı portrayed recognizable objects entirely

divorce d from their normal context. By placing objects

into unrecognizable relationships, Dal

ı c reated a dis-

turbing world in which the irrational had become

tangible.

Probing the Unconscious

Interest in the unconscious, evident in Surrealism, was

also apparent in the development of new literary tech-

niques that emerged in the 1920s. One of its most apparent

manifestations was in the ‘‘stream of consciousness’’

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

AR

EVOLUTION IN THE ARTS

The period between 1880 and 1930 witnessed a

revolution in the arts throughout Western civiliza-

tion. Fueled in part by developments in physics

and psychology, artists and writers rebelled against

the traditional belief that the task of art was to represent

‘‘reality’’ and experimented with innovative new techniques in

order to approach reality from a totally fresh perspective.

From Impressionism and Expressionism to Cubism, abstract art,

Dadaism, and Surrealism, painters seemed intoxicated with the belief

that their canvases would help reveal the radically changing world.

Especially after the cataclysm of World War I, which shattered the

image of a rational society, artists soug ht an absolute freedom of ex-

pression, confident that art could redefine humanity in the midst of

chaos. Other arts soon followed their lead: James Joyce turned prose

on its head by focusing on his characters’ innermost thoughts, and

Arnold Scho

¨

nberg created atonal music by using a scale composed

of twelve notes independent of any tonal key.

This revolutionary spirit is exemplified by Pablo Picasso’s can-

vas Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, painted in 1907 (see the illustration

on p. 510). Picasso used geometrical designs to create a new reality

and appropriated other cultural resources, including African masks,

in his effor t to revitalize Western art.

Another example of the revolutionary approach to art was the

decision by the French artist Marcel Duchamp to enter a porcelain

urinal in a 1917 art exhibit held in New York City. By signing it and

giving it the title ‘‘Fountain,’’ Duchamp proclaimed that he had

transformed the urinal into a work of art. His ‘‘ready-mades’’ (as

such art would henceforth be labeled) declared that art was whatever

the artist proclaimed as art.

Such intentionally irreverent acts demystified the nearly sacred

reverence that had traditionally been attached to works of ar t.

Essentially, Duchamp and others cla imed that anything under the

sun could be selected as a work of ar t because the mental choice

itself equaled the a ct of artistic creation. Therefore, a rt need not be

a manua l construct; it need only be a mental conceptualization.

This lib erating concept opened the floodgates of the ar t world,

allowing the new century to swim in this free-flowing, explorator y

torrent.

Q

How was the revolution in the arts between 1880 and 1930

related to the political, economic, and social developments of

the same period?

Hannah Ho

¨

ch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the

Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany. Hannah

Ho

¨

ch, a prominent figure in the postwar Dada movement, used

photomontage to create images that reflected on women’s issues. In Cut

with the Kitchen Knife, she combined pictures of German political leaders

with sports stars, Dada artists, and scenes from urban life. One major

theme emerged: the confrontation between the anti-Dada world of German

political leaders and the Dada world of revolutionary ideals. Ho

¨

ch

associated women with Dada and the new world.

c

2008 Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY

IN PURSUIT OF A NEW REALITY:CULTURAL AND IN TELLECTUAL TRENDS 585