Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

it enacted a land reform program that redefined the do-

main lands as the private property of the tillers while

compensating the previous owner with government

bonds. One reason for the new policy was that the gov-

ernment needed operating revenues. To remedy the

problem, the Meiji leaders added a new agriculture tax,

which was set at an annual rate of 3 percent of the esti-

mated value of the land. The new tax proved to be a

lucrative and dependable source of income for the gov-

ernment, but it was onerous for the farmers, who had

previously paid a fixed percentage of their harvest to the

landowner. As a result, in bad years, many taxpaying

peasants were unable to pay their taxes and were forced to

sell their lands to wealthy neighbors. Eventually, the

government reduced the tax to 2.5 percent of the land

value. Still, by the end of the century, about 40 percent of

all farmers were tenants.

With its budget needs secured, the government

turned to the promotion of industry with the basic ob-

jective of guaranteeing Japan’s survival against the chal-

lenge of Western imperialism. Building on the small but

growing industrial economy that already existed under

the Tokugawa, the Meiji reformers provided a massive

stimulus to Japan’s industrial revolution.

The government provided financial subsidies

to needy industries, training, foreign ad-

visers, improved transport and communi-

cations, and a universal educational system

emphasizing applied science. In contrast to

China, Japan was able to achieve results with

minimum reliance on foreign capital.

During the late Meiji era, Japan’s in-

dustrial sector began to grow. Besides tea

and silk, other key industries were weaponry,

shipbuilding, and sake (fermented rice

wine). From the start, the distinctive feature

of the Meiji model was the intimate rela-

tionship between government and private

business in terms of operations and regu-

lations. Once an individual enterprise or

industry was on its feet (or, sometimes,

when it had ceased to make a profit), it was

turned over entirely to private ownership,

although the government often continued to

play some role even after its direct involve-

ment in management was terminated. One

historian has explained the process:

[The Meiji government] pioneered many in-

dustrial fields and sponsored the development

of others, attempting to cajole businessmen

into new and risky kinds of endeavor, helping

assemble the necessary capital, forcing weak

companies to merge into stronger units, and

providing private entrepreneurs with aid and privileges of a

sort that would be corrupt favoritism today. All this was in

keeping with Tokugawa traditions that business operated

under the tolerance and patronage of government. Some of

the political leaders even played a dual role in politics and

business.

4

From the workers’ perspective, the Meiji reforms had

a less attractive side. As we have seen, the new land tax

provided the funds to subsidize the growth of the in-

dustrial sector, but it imposed severe hardships on the

rural population, many of whom abandoned their farms

and fled to the cities, where they provided an abundant

source of cheap labor for Japanese industry. As in Europe

during the early decades of the Industrial Revolution,

workers toiled for long hours in the coal mines and textile

mills, often under horrendous conditions. Reportedly,

coal miners employed on a small island in Nagasaki

Harbor worked naked in temperatures up to 130 degrees

Fahrenheit. If they tried to escape, they were shot.

Building a Modern Social Structure By the late To-

kugawa era, the rigidly hierarchical social order was

showing signs of disintegration. Rich merchants were

The Emperor Inspect s Hi s Domain. A crucial challenge for the Japanese government

during the Meiji era was to provide for the food needs of the country by increasing the

productivity of agricultural workers. In this painting, Emperor Meiji inspects farmers planting

rice seedlings in a flooded field. The practice of showing the imperial face in public was an

innovation introduced by Emperor Meiji that earned him the affection of his subjects.

Collection Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Tokyo, Japan/

c

Art Resource, NY

556 CHAPTER 22 SHADOWS OVER THE PACIFIC: EAST ASIA UNDER CHALLENGE

buying their way into the ranks of the samurai, and

Japanese of all classes were beginning to abandon their

rice fields and move into the growing cities. Nevertheless,

community and hierarchy still formed the basis of Japa-

nese society. The lives of all Japanese were determined by

their membership in various social organizations---the

family, the village, and their social class. Membership in a

particular social class determined a person’s occupation

and social relationships with others. Women in particular

were constrained by the ‘‘three obediences’’ imposed on

their gender: child to father, wife to husband, and widow

to son. Husbands could easily obtain a divorce, but wives

could not (one regulation allegedly decreed that a hus-

band could divorce his spouse if she drank too much tea

or talked too much). Marriages were arranged, and the

average age at marriage for females was sixteen years.

Females did not share inheritance rights with males, and

few received any education outside the family.

The Meiji reformers destroyed much of the tradi-

tional social system in Japan. With the abolition of he-

reditary rights in 1871, the legal restrictions of the past

were brought to an end with a single stroke. Special

privileges for the aristocracy were abolished, as were the

legal restrictions on the eta, the traditional slave class

(numbering about 400,000 in the 1870s). Another key

focus of the reformers was the army. The Sat-Cho re-

formers had been struck by the weakness of the Japanese

forces in clashes with Western powers and embarked on a

major program to create a military force that could

compete in the modern world. The old feudal army based

on the traditional warrior class was abolished, and an

imperial army based on universal conscription was

formed in 1871.

Education also underwent major changes. The Meiji

leaders recognized the need for universal education in-

cluding technical subjects, and after a few years of ex-

perimenting, they adopted the American model of a

three-tiered system culminating in a series of universities

and specialized institutes. In the meantime, they sent

bright students to study abroad and brought foreign

scholars to Japan to teach in the new schools, where

much of the content was inspired by Western models. In

another break with tradition, women for the first time

were given an opportunity to get an education.

Western influence was evident elsewhere as well.

Western fashions became the rage in elite circles, and the

ministers of the first Meiji government were known as the

‘‘dancing cabinet’’ because of their addiction to Western-

style ballroom dancing. Young people, increasingly ex-

posed to Western culture and values, began to imitate the

clothing styles, eating habits, and social practices of their

European and American counterparts. They even took up

American sports when baseball was introduced.

Traditional Values and Women’s Rights The self-

proclaimed transformation of Japan into a ‘‘modern so-

ciety,’’ however, by no means detached the country en-

tirely from its traditional moorings. Although an

educational order in 1872 increased the percentage of

Japanese women exposed to public education, con-

servatives soon began to impose restrictions and bring

about a return to more traditional social relationships.

Traditional values were given a firm legal basis in the

Constitution of 1890, which restricted the franchise to

males and defined individual liberties as ‘‘subject to the

limitations imposed by law,’’ and by the Civil Code of

1898, which de-emphasized individual rights and essen-

tially placed women within the context of their role in the

family (see the box on p. 558).

By the end of the nineteenth century, however,

changes were under way as women began to play a crucial

role in their nation’s effort to modernize. Urged by their

parents to augment the family income, as well as by the

government to fulfill their patriotic duty, young girls were

sent en masse to work in textile mills. From 1894 to 1912,

women represented 60 percent of the Japanese labor

force. Thanks to them, by 1914, Japan was the world’s

leading exporter of silk and dominated cotton

manufacturing. If it had not been for the export revenues

earned from textile exports, Japan might not have been

able to develop its heavy industry and military prowess

without an infusion of foreign capital.

Japanese women received few rewards for their

contribution to the nation, however. In 1900, new regu-

lations prohibited women from joining political organi-

zations or attending public meetings. Beginning in 1905,

a group of independent-minded women petitioned the

Japanese parliament to rescind this restriction, but it was

not repealed until 1922.

Joining the Imperialist Club

Traditionally, Japan had not been an expansionist coun-

try. Now, however, the Japanese did not just imitate the

domestic policies of their Western mentors; they also

emulated the Western approach to foreign affairs. This is

perhaps not surprising. The Japanese regarded themselves

as particularly vulnerable in the world economic arena.

Their territory was small, lacking in resources, and

densely populated, and they had no natural outlet for

expansion. To observant Japanese, the lessons of history

were clear. Western nations had amassed wealth and

power not only because of their democratic systems and

high level of education but also because of their colonies.

The Japanese began their program of territorial ex-

pansion close to home (see Map 22.4). In 1874, after a

brief conflict with China, Japan was able to claim

ARICH COUNTRY AND A STRONG STATE:THE RIS E OF MODERN JAPAN 557

suzeraint y over the Ryukyu Islands, long tributary to the

Chinese Empire. Two years later, Japanese naval pressure

forced Korea to open three ports to Japanese commerce.

During the early decades of the nineteenth century,

Korea had followed Japan’s example and attempted to

isolate itself from outside contact except for periodic

tribute missions to China. Christian missionaries, mostly

Chinese or French, were vigorously persecuted. But

Korea ’s problems were basically internal. In the early 1860s,

a peasant revolt, inspired in part by the Taiping Rebellion

in China, caused considerable devastation before being

crushed in 1864. In succeeding years, the Yi dynasty

sought to strengthen the country by returning to tradi-

tional values and fending off outside intrusion, but rural

poverty and official corruption remained rampant. A U.S.

fleet, following the example of Commodore Perry in

Japan, sought to open the country in 1871 but was driven

off with considerable loss of life.

Korea’s most persistent suitor, however, was Japan,

which was determined to bring an end to Korea’s de-

pendency status with China and modernize it along

Japanese lines. In 1876, the two countries signed an

agreement opening three treaty ports to Japanese com-

merce in return for Japanese recognition of Korean in-

dependence. During the 1880s, Sino-Japanese rivalry over

Korea intensified. When a new peasant rebellion broke

out in Korea in 1894, China and Japan intervened on

opposite sides (see the box on p. 559). During the war, the

Japanese navy destroyed the Chinese fleet and seized

the Manchurian city of Port Arthur. In the Treaty of

THE RULES OF GOOD CITIZENSHIP IN JAPAN

After seizing power from the Tokugawa shogunate

in 1868, the new Japanese leaders turned their

attention to the creation of a new political system

that would bring the country into the modern world.

After exploring various systems in use in the West, a constitu-

tional commission decided to adopt the system used in imperial

Germany because of its paternalistic character. To promote

civic virtue and obedience among the citizenry, the government

then drafted an imperial rescript that was to be taught to every

schoolchild in the country. The rescript instructed all children to

obey their sovereign and place the interests of the community

and the state above their own personal desires.

Imperial Rescript on Education, 1890

Know ye, Our subjects:

Our Imperial Ancestors have founded Our Empire on a basis

broad and everlasting, and have deeply and firmly implanted v irtue.

Our subjects ever united in loyalty and filial piety have from

generation to generation illustrated the beauty thereof. This is the

glory of the fundamental character of Our Empire, and herein also

lies the source of Our education. Ye, Our subjects, be filial to your

parents, affectionate to your brothers and sisters, as husbands and

wives be harmonious, as friends true; bear yourselves in modesty

and moderation; extend your benevolence to all; pursue learning

and cultivate ar ts, and thereby develop intellectual faculties and per-

fect moral powers; furthermore, advance public good and promote

common interests; always respect the Constitution and observe the

laws; should emergency arise, offer yourselves to the State; and thus

guard and maintain the prosperity of Our Imperial Throne coeval

with heaven and earth. So shall ye not only be Our good and faith-

ful subjects, but render illustrious the best traditions of your

forefathers.

Q

What, according to this document, was the primary

purpose of education in Meiji Japan? How did these goals

compare with those in China and the West?

A

m

u

r

R

.

R

U

S

S

I

A

M

A

N

C

H

U

R

I

A

TAIWAN

(FORMOSA)

1895

KARAFUTO

1905

KOREA

1908

FUJIAN

SHANDONG

SAKHALIN

S

O

U

T

H

M

A

N

C

H

U

R

I

A

R

Y

U

K

Y

U

I

S

.

1

8

7

4

K

U

R

I

L

E

I

S

.

1

8

7

5

J

A

P

A

N

Pacific

Ocean

Sea of Japan

(East Sea)

Straits of Tsushima

C

H

I

N

A

Qingdao

Changchun

Amoy

Port Arthur

Liaodong

Peninsula

Japan’s possessions at

the end of 1875

Territorial acquisitions,

1894–1914

Spheres of Japanese

influence in 1918

0 250 500 Miles

0 500 1,000 Kilometers

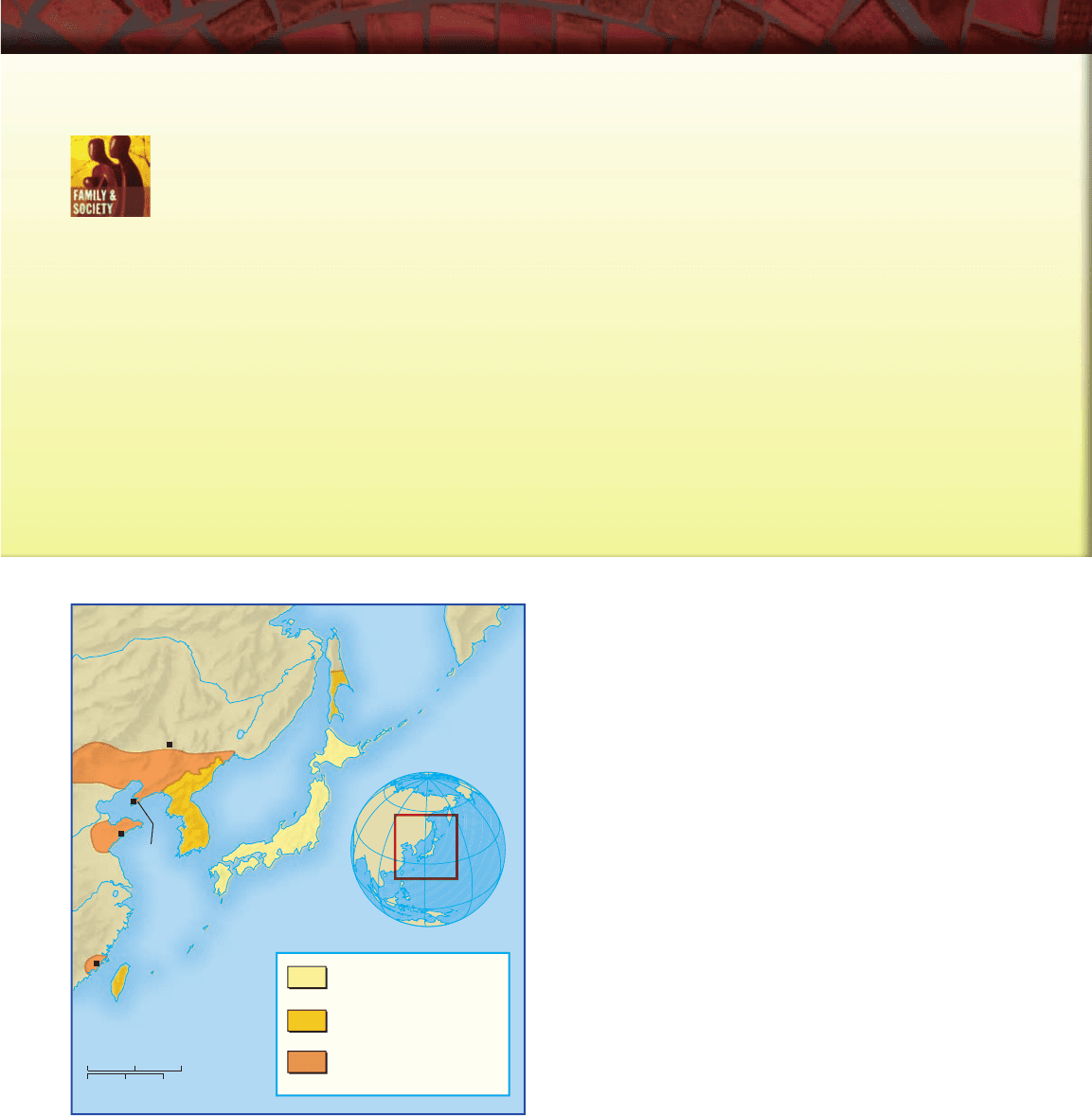

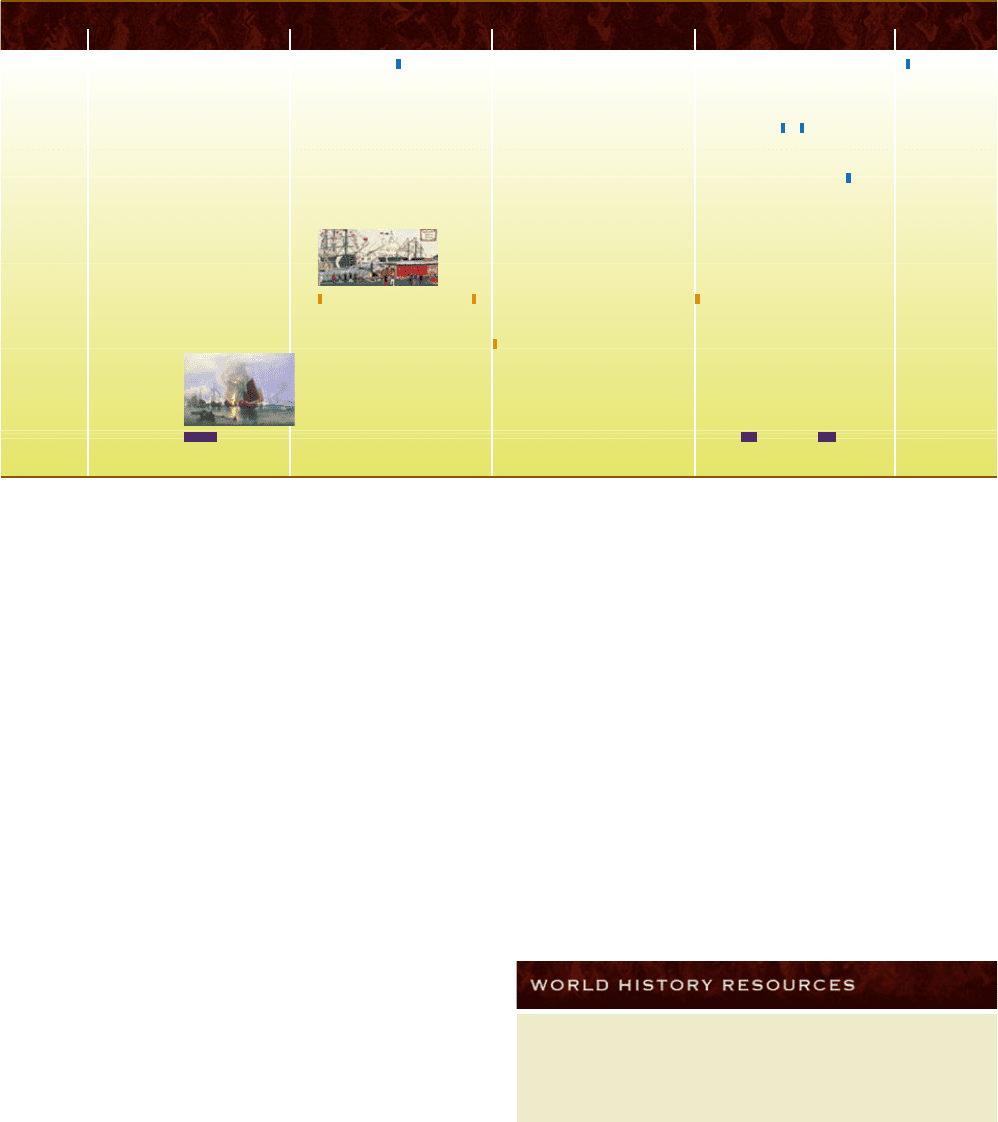

MAP 22.4 Japanese Oversea s Ex pansion During the

Meiji Era.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Japan

ventured beyond its home islands and became an imperialist

power. The extent of Japanese colonial expansion through

World War I is shown here.

Q

Which parts of imperial China came under Japanese

influence?

558 CHAPTER 22 SHADOWS OVER THE PACIFIC: EAST ASIA UNDER CHALLENGE

Shimonoseki, the Chinese were forced to recognize the

independence of Korea and cede Taiwan and the Liao-

dong peninsula with its strategic naval base at Port Arthur

to Japan.

Shortly thereafter, under pressure from the European

powers, the Japanese returned the Liaodong peninsula to

China, but in the early twentieth century, they went back

on the offensive. Rivalry with Russia over influence in

Korea led to increasingly strained relations between the

two countries. In 1904, Japan launched a surprise attack

on the Russian naval base at Port Arthur, which Russia

had taken from China in 1898. The Japanese armed forces

were weaker, but Russia faced difficult logistical problems

along its new Trans-Siberian Railway and severe political

instability at home. In 1905, after Japanese warships sank

almost the entire Russian fleet off the coast of Korea, the

Russians agreed to a humiliating peace, ceding the stra-

tegically located Liaodong peninsula back to Japan, as

well as southern Sakhalin and the Kurile Islands. Russia

also agreed to abandon its political and economic influ-

ence in Korea and southern Manchuria, which now came

increasingly under Japanese control. The Japanese victory

stunned the world, including the colonial peoples of

Southeast Asia, who now began to realize that the white

race was not necessarily invincible.

During the next few years, the Japanese consolidated

their position in northeastern Asia, annexing Korea in

1908 as an integral part of Japan. When the Koreans

OPPOSING VIEWPOINTS

T

WO VIEWS OF THE WORLD

During the nineteenth century, China’s hierarchical

way of looking at the outside world came under se-

vere challenge, not only from European countries

avid for new territories in Asia but also from the

rising power of Japan, which accepted the Western view that a

colonial empire was the key to national greatness. Japan’s first

objective was Korea, long a dependency of China, and in 1894,

the competition between China and Japan in the Korean penin-

sula led to war. The following declarations of war by the rulers

of the two countries are revealing. Note the Chinese use of the

derogatory term Wojen (‘‘dwarf people’’) in referring to the

Japanese.

Declaration of War Against China

Korea is an independent state. She was first introduced into the

family of nations by the advice and guidance of Japan. It has, how-

ever, been China’s habit to designate Korea as her dependency, and

both openly and secretly to interfere with her domestic affairs. At

the time of the recent insurrection in Korea, China despatched

troops thither, alleging that her purpose was to afford a succor to

her dependent state. We, in virtue of the treaty concluded with

Korea in 1882, and looking to possible emergencies, caused a

military force to be sent to that country.

Wishing to procure for Korea freedom from the calamity of

perpetual disturbance, and thereby to maintain the peace of the East

in general, Japan invited China’s cooperation for the accomplish-

ment of the object. But China, advancing various pretexts, declined

Japan’s proposal. ... Such conduct on the part of China is not only

a direct injury to the rights and interests of this Empire, but also a

menace to the permanent peace and tranquility of the Orient. ... In

this situation, ...we find it impossible to avoid a formal declaration

of war against China.

Declaration of War Against Japan

Ko rea has been our tributary for the past two hundred odd years.

She has given us tribute all this time, which is a matter known to

the world. For the past dozen years or so Korea has been troubled

by repeated insurrections and we, in sympathy with our small trib-

utary, have as repea tedly sen t succor to her aid . ... This year an-

other rebellion was begun in Korea, and the King repeatedly asked

again for aid from us to put down the rebellion. We then ordered

Li Hung-chang to send troops to Korea; and they having barely

reached Yashan the rebels immediately scattered. But the Wojen,

wi thout any cause whatever, suddenly sent their troops to Korea,

and entered Seoul, the capital of Korea, reinforcing them con-

stantly until they have exceeded ten thousand men . In the mean-

time the Japanese forced the Korean king to change his system of

government, showing a disposition ever y way of bullying the

Ko reans. ...

As Japan has violated the treaties and not observed interna-

tional laws, and is now running rampant with her false and treach-

erous actions commencing hostilities herself, and laying herself open

to condemnation by the various powers at large, we therefore desire

to make it known to the world that we have always followed the

paths of philanthropy and perfect justice throughout the whole

complications, while the Wojen, on the other hand, have broken all

the laws of nations and treaties which it passes our patience to bear

with. Hence we commanded Li Hung-chang to give strict orders to

our various armies to hasten with all speed to root the Wojen out of

their lairs.

Q

Compare the worldviews of China and Japan at the end

of the nineteenth century as reflected in these two declarations.

Which point of view do you find more persuasive?

ARICH COUNTRY AND A STRONG STATE:THE RIS E OF MODERN JAPAN 559

protested the seizure, Japanese reprisals resulted in

thousands of deaths. The United States was the first na-

tion to recognize the annexation in return for Tokyo’s

declaration of respect for U.S. authority in the Philip-

pines. In 1908, the United States recognized Japanese

interests in the region in return for Japanese acceptance of

the principles of the Open Door. But mutual suspicion

between the two countries was growing, sparked in part

by U.S. efforts to restrict immigration from all Asian

countries.

Japanese Culture in Transition

The wave of Western technology and ideas that entered

Japan in the second half of the nineteenth century

greatly altered the shape of traditional Japanese culture.

Literature in particular was affected as European models

eclipsed the repetitive and frivolous tales of the Toku-

gawa era. Dazzled by this ‘‘new’’ literature, Japanese

authors began translating and imitating t he imported

models. Experimenting with Western verse, Japanese

poets were at first influenced primarily by the British but

eventually adopted such French style s as Symbolism,

Dadaism, and Surrealism, although some traditional

poetry was still composed.

As the Japanese invited technicians, engineers, archi-

tects, and artists from Eur ope and the U nited States to

teach their ‘‘modern’’ skills to a generation of eager stu-

dents, the Meiji era became a time of massive consumption

of Western artistic techniques and styles. Japanese archi-

tects and artists created huge buildings of steel and re-

inforced concr ete adorned with Greek columns and

cupolas, oil paintings reflecting the European concern with

depth perc eption and shading, and bronze sculptures of

secular subjects.

Cultural exchange also went the other way as Jap-

anese arts and crafts, porcelains, text iles, fans, f olding

screens, and woodblock prints became the vogue in

Europe and North America. Japanese art influenced

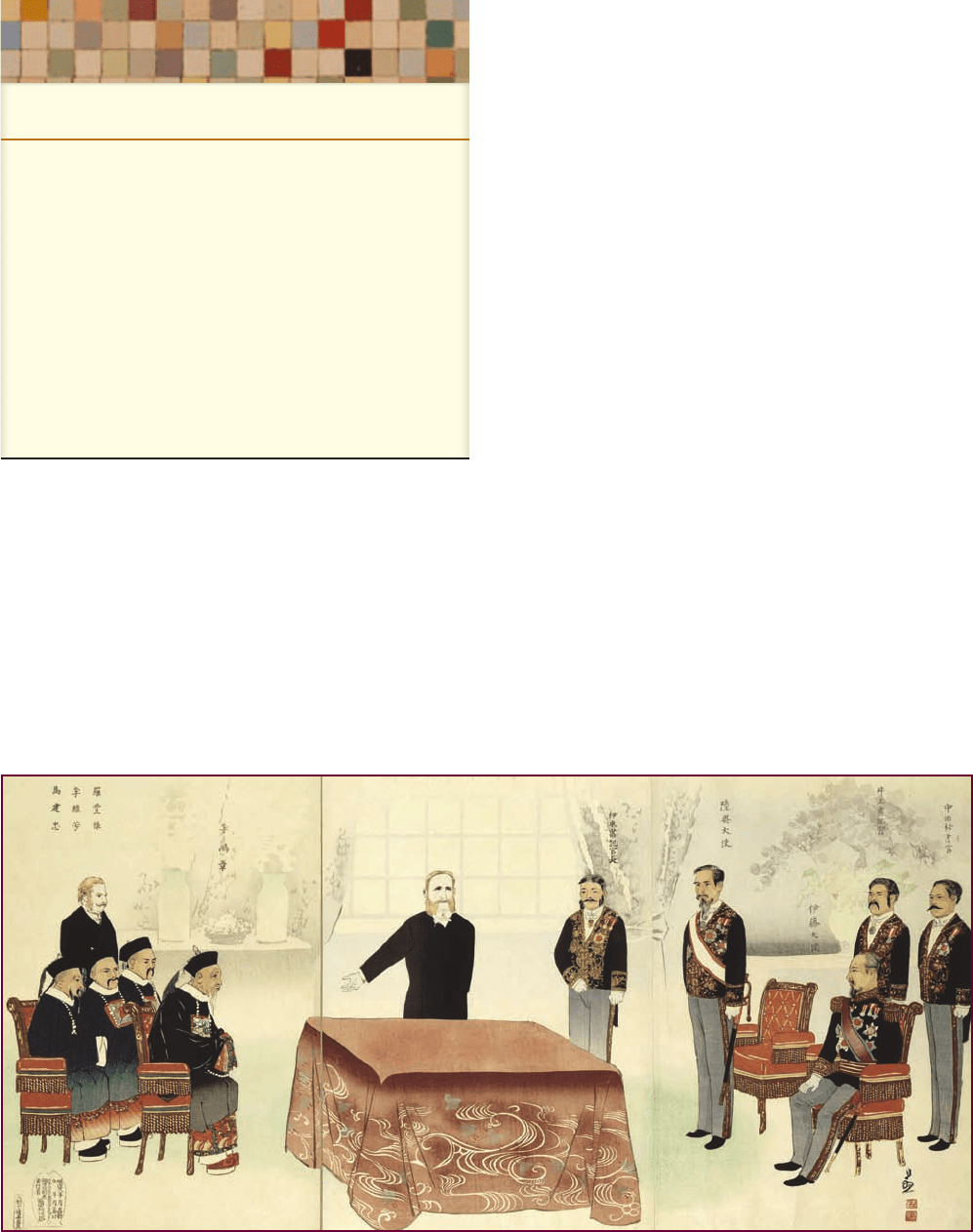

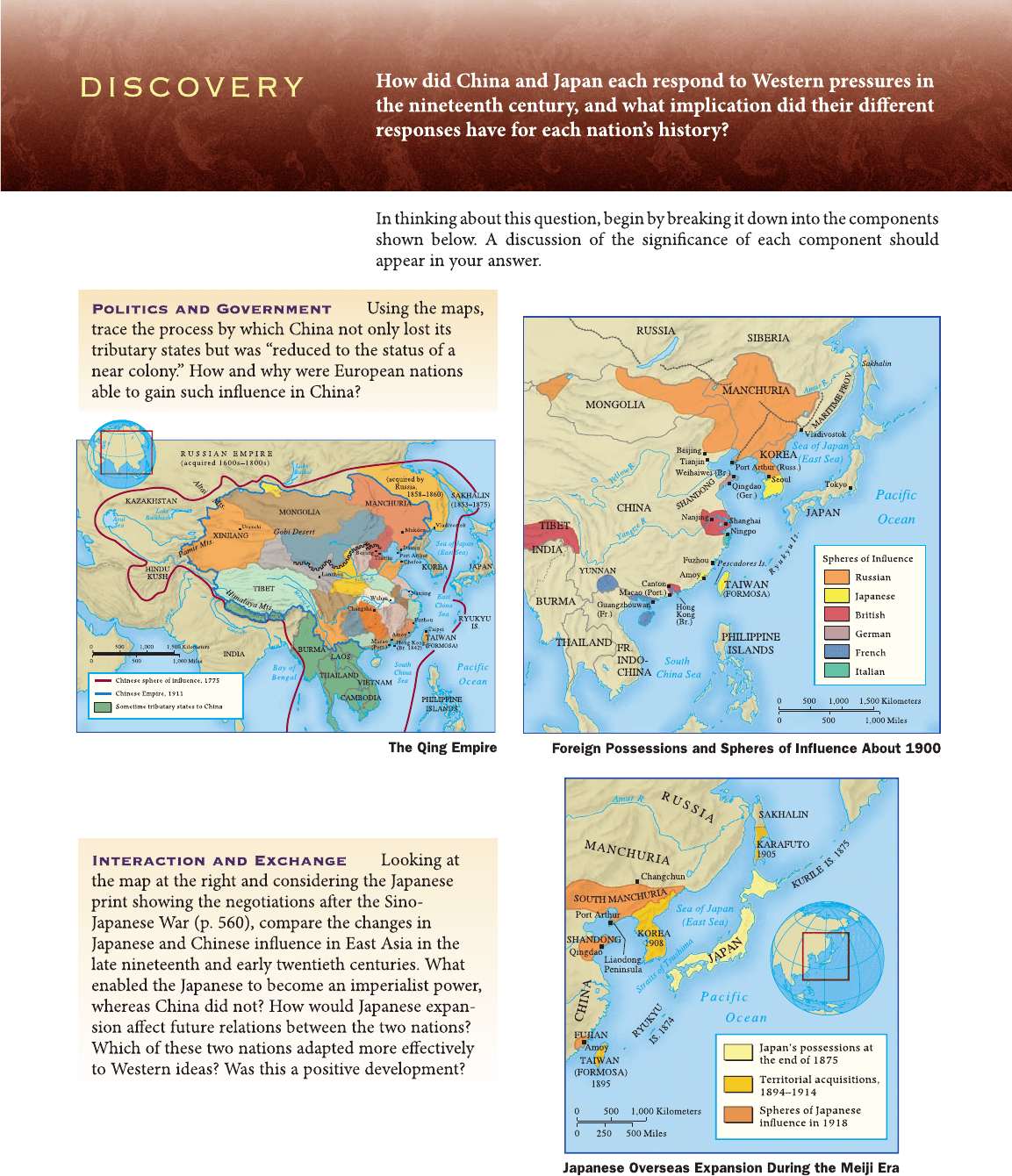

Total Humiliati on. Whereas China had persevered in hiding behind the grandeur of its past, Japan had

embraced the West, modernizing itself politically, militarily, and culturally. China’s humiliation at the hands of

its newly imperialist neighbor is evident in this scene, where the differences in dress and body posture of the

officials negotiating the treaty after the war reflect China’s disastrous defeat by the Japanese in 1895.

CHRONOL OGY

JapanandKoreaintheEra

of Imperialism

Commodore Perry arrives in Tokyo Bay 1853

Townsend Harris Treaty 1858

Fall of Tokugawa shogunate 1868

U.S. fleet fails to open Korea 1871

Feudal titles abolished in Japan 1871

Japanese imperial army formed 1871

Meiji Constitution adopted 1890

Imperial Rescript on Education 1890

Treaty of Shimonoseki awards Taiwan to Japan 1895

Russo-Japanese War 1904--1905

Korea annexed by Japan 1908

c

R

eunion des Mus

ees Nationaux/Art Resource, NY

560 CHAPTER 22 SHADOWS OVER THE PACIFIC: EAST ASIA UNDER CHALLENGE

We stern painters such as Vincent van Gogh, Edgar

Degas, and James Whistler, who experimented with

flatter compositional perspectives and unusual poses.

Japanese gardens, w ith their exquisite attention to the

positioning of rocks and falling water, also became es-

pecially popular.

After the initial period of mass absorption of

Weste rn art, a nati onal reaction occurred at the end of

the nineteenth century as many artists returned to pre-

Meiji techniques. In 1889, the Tokyo School of Fine Arts

(today the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and

Music) was founded to promote traditional Japanese a rt.

Over the next several decades, Japanese art underwent a

dynamic resurgence, reflec ting the na tion’s emergence as

a prosperous and powerful state. While some Japanese

artists attempted to synthesize nati ve and foreign tech-

niques, others retu rned to past artistic tra ditions for

inspiration.

The Meiji Restoration:

A Revolution from Above

Japan’s transformation from a feudal, agrarian society

to an industrializing, technologically advanced societ y

in little more than half a

century has frequently been

described by outside

observers (if not by the Jap-

anese themselves) in almost

miraculous terms. Some his-

torians have questioned this

characterization, pointing

out that the achievements of

the Meiji leaders were spotty.

In Japan’s Emergence as a

Modern State, the Canadian

historian E. H. Norman

lamented that the Meiji Res-

toration was an ‘‘incomplete

revol ution’’ because it had

not ended the economic and

social inequities of feudal

society or enabled the com-

monpeopletoparticipate

fully in the governing pro-

cess. Although the genro were

enlightened in many respects,

they were also despotic and

elitist, and the distribution of

wealth remained as unequal

as it had been under the old

system.

5

These criticisms are persuasive, although they could

also be applied to most other societies going through the

early stages of industrialization. In any event, from an

economic perspective, the Meiji Restoration was certainly

one of the great success stories of modern times. Not only

did the Meiji leaders put Japan firmly on the path to

economic and political development, but they also

managed to remove the unequal treaty provisions that

had been imposed at mid-century. Japanese achievements

are especially impressive when compared with the diffi-

culties experienced by China, which was not only unable

to realize significant changes in its traditional society but

had not even reached a consensus on the need for doing

so. Japan’s achievements more closely resemble those of

Europe, but whereas the West needed a century and a half

to achieve a significant level of industrial development,

the Japanese realized it in forty years.

One of the distinctive features of Japan’s transition

from a traditional to a modern society during the Meiji

era was that it took place for the most part without

violence or the kind of social or political revolution that

occurred in so many other countries. The Meiji Resto-

ration, which began the process, has been called a ‘‘rev-

olution from above,’’ a comprehensive restructuring of

Japanese society by its own ruling group.

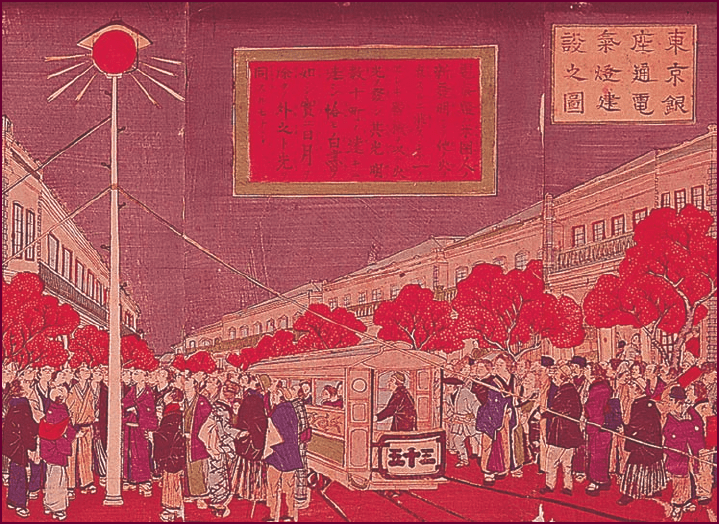

The Gin za in Downtown Tokyo. This 1877 woodblock print shows the Ginza, a major commercial

thoroughfare in downtown Tokyo, with modern brick buildings, rickshaws, and a horse-drawn streetcar. The

centerpiece and focus of public attention is a new electric streetlight. In combining traditional form with modern

content, this print symbolizes the unique ability of the Japanese to borrow ideas from abroad while preserving

much of the essence of their traditional culture.

c

Art Resource, NY

ARICH COUNTRY AND A STRONG STATE:THE RIS E OF MODERN JAPAN 561

Sources of Japanese Uniqueness The differences

between the Japanese response to the West and that of

China and many other nations in the region have sparked

considerable debate among students of comparative his-

tory, and a number of explanations have been offered.

Some have argued that Japan’s success was partly due to

good fortune. Lacking abundant natural resources, it was

exposed to less pressure from the West than many of its

neighbors. That argument is problematic, however, and

would probably not have been accepted by Japanese ob-

servers at the time. Nor does it explain why nations under

considerably less pressure, such as Laos and Nepal, did

not advance even more quickly. All in all, the luck hy-

pothesis is not very persuasive.

Some explanations have already been suggested in

this book. Japan’s unique geographic position in Asia was

certainly a factor. China, a continental nation with a

heterogeneous ethnic composition, was distinguished

from its neighbors by its Confucian culture. By contrast,

Japan was an island nation, ethnically and linguistically

homogeneous, and had never been conquered. Unlike the

Chinese or many other peoples in the region, the Japanese

had little to fear from cultural change in terms of its effect

on their national identity. If Confucian culture, with all

its accouterments, was what defined the Chinese gentle-

man, his Japanese counterpart, in the familiar image,

could discard his sword and kimono and don a modern

military uniform or a Western business suit and still feel

comfortable in both worlds.

Fusing East and West The final product was an

amalgam of old and new, native and foreign, forming a

new civilization that was still uniquely Japanese. There

were some undesirable consequences, however. Because

Meiji politics was essentially despotic, Japanese leaders

were able to fuse key t raditional elements such as the

warrior ethic and the concept of feudal loyalty with the

dynamics of modern industrial capitalism to create a

state totally dedicated to the possession of material

wealth and national power. This combination of kokutai

and capitalism was hig hly effective but explosive in its

international manifestation. Like modern Germany,

which also entered the industrial age directly from

feudalism, Japan eventually engaged in a pol icy of

repression at home and expansion abroad in order

to achieve its national objectives (see the comparative

essay ‘‘Paths to Modernization’’ on p. 634 in Chapter 25).

In Japan, as in Germany, it took defeat in war to dis-

connect the drive for national development from the

feudal ethic and bring about the transformation to

a pluralistic society dedicated to living in peace and

cooperation with its neighbors.

CONCLUSION

FEW AREAS OF THE WORLD resisted the Western incursion

as stubbornly and effectively as E ast Asia. Although military,

political, and economic pressure by the European powers was

relatively intense during this era, two of the main states in the area

were able to retain their independence (although China admittedly

was reduced to the status of a near colony during the first quarter

of the twentieth century) while the third---Korea---was temporarily

absorbed by one of its larger neighbors. Why the Chinese and the

Japanese were able to prevent a total political and military

takeover by foreign powers is an interesting question. One key

reason was that both had a long history as well-defined states with

a strong sense of national community and territorial cohesion.

Although China had frequently been conquered, it had retained its

sense of unique culture and identit y. Geography, too, was in its

favor. As a continental nation, China was able to sur vive partly

because of its sheer s ize. Japan possessed the advantage of an

island location.

Even more striking, however, is the different way in which the

two states attempted to deal with the challenge. While the Japanese

chose to face the problem in a pragmatic manner, borrowing

foreign ideas and institutions that appeared to be of value and at the

same time were not in conflict with traditional attitudes and

customs, China agonized over the issue for half a centur y while

conservative elements fought a desperate battle to retain a

maximum of the traditional heritage intact.

This chapter has discussed some of the possible reasons

for those d ifferences. In retrospect, it is difficult to avoid the

conclusion that the Japanese approach was the more effective

one. Whereas the Meiji leaders were able to set in motion an

orderly transition from a traditional to an advanced society, in

China the old system collapsed in disorder, leaving chaotic

conditions that were still not rectified a generation later. China

would pay a heavy price for its failure to respond coherently to

the challenge.

But the Japanese ‘‘revolution from above’’ was by no means an

unalloyed success. Ambitious efforts by Japanese leaders to carve

out a share in the spoils of empire led to escalating conflict with

China as well as with rival Western powers and in the early 1940s to

global war. We will deal with that issue in Chapter 25. Meanwhile, in

Europe, a combination of old rivalries and the effects of the

Industrial Revolution were leading to a bitter regional conflict that

eventually engulfed the entire world.

562 CHAPTER 22 SHADOWS OVER THE PACIFIC: EAST ASIA UNDER CHALLENGE

SUGGESTED READING

China For a general overview of modern Chinese histor y, see

I. C. Y. Hsu, The Rise of Modern China, 6th ed. (Oxford, 2000).

Also see J. Spence’s stimulating work The Search for Modern China

(New York, 1990).

On the Taiping Rebellion, J. Spence, God’s Chinese Son: The

Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan (New York, 1996), has

become a classic. Social issues are dealt with in E. S. Rawski, The Last

Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions (Berkeley ,

Calif., 1998). On the Manchus’ attitude toward modernization, see

D. Pong, Shen Pao-chen and China’ s Modernization in the

Nineteenth Century (New York, 1994). For a series of stimulating

essays on various aspects of China’s transition to modernity, see

Wenhsin Yeh, ed., Becoming Chinese: Passages to Modernity and

Beyond (Berkeley, Calif., 2000).

Sun Yat-sen’s career is explored in M. C. Berg

ere, Sun Yat-sen,

trans. J. Lloyd (Stanford, Calif., 2000). S. Seagraves’s Dragon Lady:

The Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China (New York, 1992)

is a revisionist treatment of Empress Dowager Cixi. On the Boxer

Rebellion, the definitive work is J. Esherick, The Origins of the Boxer

Uprising (Berkeley, Calif., 1987). Also see D. Preston, The Boxer

Rebellion: The Dramatic Story of China’s War on Foreigners That

Shook the World in the Summer of 1900 (Berkeley, Calif., 2001).

Japan The Meiji period of modern Japan is covered in M. B.

Jansen, ed., The Emergence of Meiji Japan (Cambridge, 1995).

Also see D. Keene, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World,

1852--1912 (New York, 2000). See also C. Gluck, Japan’s Modern

Myths: Ideology in the Late Meiji Period (Princeton, N.J., 1985).

On the economy, see R. Smethurst, Agricultural Development and

Tenancy Disputes in Japan, 1870--1940 (Princeton, N.J., 1986), and

M. Hane, Peasants, Rebels, and Outcastes: The Underside of

Modern Japan (New York, 1982). To understand the role of the

samurai in the Meiji Revolution, see E. Ikegami, The Taming of the

Samurai: Honorific Individualism and the Making of Modern

Japan (Cambridge, 1995).

On the international scene, W. Lafeber, The Clash: U.S.-

Japanese Relations Throughout History (New York, 1997), is slow

reading but a good source of information. Also see M. Peattie and

R. Myers, The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895--1945 (Princeton,

N.J., 1984). The best introduction to Japanese art is P. Mason,

History of Japanese Art (New York, 1993). See also J. S. Baker’s

concise Japanese Art (London, 1984).

TIMELINE

1830

1850 1870 1890 1910

China

Japan

Collapse of Tokugawa shogunate

Opium War Russo-Japanese War

Meiji Constitution adopted

Abolition of

feudalism in Japan

Manchus suppress

Taiping Rebellion

Sun Yat-sen’s forces

overthrow Manchu dynasty

One Hundred

Days reform

Boxer Rebellion

Sino-Japanese War

Commodore Perry

arrives in Tokyo Bay

Abolition of civil

service examination

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

CONCLUSION 563

564

CHAPTER 23

THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY

CRISIS: WAR AND REVOLUTION

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

The Road to World War I

Q

What were the long-range and immediate causes

of World War I?

The Great War

Q

Why did the course of World War I turn out to be

so different from what the belligerents had expected?

How did World War I affect the belligerents’

governmental and political institutions, economic

affairs, and social life?

Crisis in Russia and the End of the War

Q

What were the causes of the Russian Revolution of

1917, and why did the Bolsheviks prevail in the civil

war and gain control of Russia?

An Uncertain Peace

Q

What problems did Europe and the United States face

in the 1920s?

In Pursuit of a New Reality :

Cultural and Intellectual Trends

Q

How did the cultural and intellectual trends of the

interwar years reflect the crises of those years as well

as the experience of World War I?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

What conclusions can you draw about the impact of

World War I on European political institutions and

social structures?

British troops wait for the signal to attack.

ON JULY 1, 1916, BRITISH and French infantry forces

attacked German defensive lines along a 25-mile front near the

Somme River in France. Each soldier carried almost 70 pounds of

equipment, making it ‘‘impossible to move much quicker than a

slow walk.’’ German machine guns soon opened fire: ‘‘We were able

to see our comrades move forward in an attempt to cross No-Man’s

Land, only to be mown down like meadow grass,’’ recalled one

British soldier. ‘‘I felt sick at the sight of this carnage and remember

weeping.’’ In one day, more than 21,000 British soldiers died. After

six months of fighting, the British had advanced 5 miles; one million

British, French, and German soldiers had been killed or wounded.

Philip Gibbs, an English war correspondent, described what

he saw in the German trenches that the British forces overran:

‘‘Victory! ...Some of the German dead were young boys, too young

to be killed for old men’s crimes, and others might have been old or

young. One could not tell because they had no faces, and were just

masses of raw flesh in rags of uniforms. Legs and arms lay separate

without any bodies thereabout.’’

World War I (1914--1918) was the defining event of the twentieth

century. Overwhelmed by the size of its battles, the extent of its

casualties, and its impact on all facets of life, contemporaries

referred to it simply as the ‘‘Great War.’’ The Great War was all the

565

c

Archives Charmet/The Bridgeman Art Library