Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

placed the countries under its own rule on a wartime

basis.

Japanese leaders had hoped that their lightning strike

at American bases would destroy the U.S. Pacific fleet and

persuade President Franklin D. Roosevelt to accept Japanese

domination of the P acific. But J apan had miscalculated.

The attack on Pearl Harbor galvanized American opinion

and won broad support for Roosevelt’s war policy. The

U nited States now joined with European nations and Na-

tionalist China in a combined effort to defeat Japan and

end its hegemony in the P acific. Believing that American

inv olv ement in the Pacific would render the U nited States

ineffective in the European theater of war, Hitler declared

war on the United States four days after P earl Harbor.

The Turning Point of the War, 1942--1943

The entry of the United States into the war created a

coalition (the Grand Alliance) that ultimately defeated the

Axis Powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan). To overcome

mutual suspicions, the three major Allies, Britain, the

United States, and the Soviet Union, agreed to stress

military operations while ignoring political differences.

At the beginning of 1943, the Allies also agreed to fight

until the Axis Powers surrendered unconditionally, which

had the effect of cementing the Grand Alliance by making

it nearly impossible for Hitler to divide his foes.

Defeat, however, was far from Hitler’ s mind at the

beginning of 1942. As Japanese forces advanced into the

P acific after crippling the American naval fleet at P earl

Harbor, Hitler continued the war in Europe against Britain

and the Soviet Union. Until the fall of 1942, it appeared

that the Germans might still prevail on the battlefield.

Reinfor c ements in North Africa enabled the Afrika K orps

under General Erwin Rommel to break through the British

defenses in Egypt and advance toward Alexandria. In the

spring of 1942, a renewed German offensive in the Soviet

U nion led to the capture of the entire Crimea. But by the

fall of 1942, the war had turned against the Germans.

In North Africa, British forces had stopped Rommel’s

troops at El Alamein in the summer of 1942 and then forc ed

them back across the desert. In November 1942, British and

American forces invaded French North Africa and forced

the German and Italian troops to surrender in May 1943.

On the Eastern Front, the turning point of the war occurred

at Stalingrad. After the capture of the Crimea, Hitler de-

cided that Stalingrad, a major industrial center on the

Volga, should be taken next. Between November 1942 and

February 1943, German troops were stopped, then en-

circled, and finally forced to surrender on February 2, 1943

(see the box on p. 628). The entire German Sixth Army of

300,000 men was lost. By February 1943, German forces in

the Soviet Union were back to their positions of June 1942.

The tide of battle in the Far East also turned dramat-

ically in 1942. In the Battle of the Coral Sea on May 7--8,

1942, American naval forces stopped the Japanese advance.

On J une 4, at the Battle of Midway Island, American planes

destro yed all four of the attacking Japanese aircraft carriers

and established American naval superiority in the Pacific.

By the fall of 1942, Allied forces were beginning to gather

for offensive operations: into South China from Burma,

through the East Indies by a process of ‘‘island hopping’’ by

troops commanded by the U .S. general Douglas Mac-

Arthur , and across the P acific with a combination of U .S.

Army, Marine, and Navy attacks on Japanese-held islands.

After a series of bitter engagements in the waters of the

Solomon Islands from A ugust to Nov ember 1942, Japanese

fortunes began to fade.

The Last Years of the War

By the beginning of 1943, the tide of battle had turned

against Germany, Italy, and Japan. After the Axis forces had

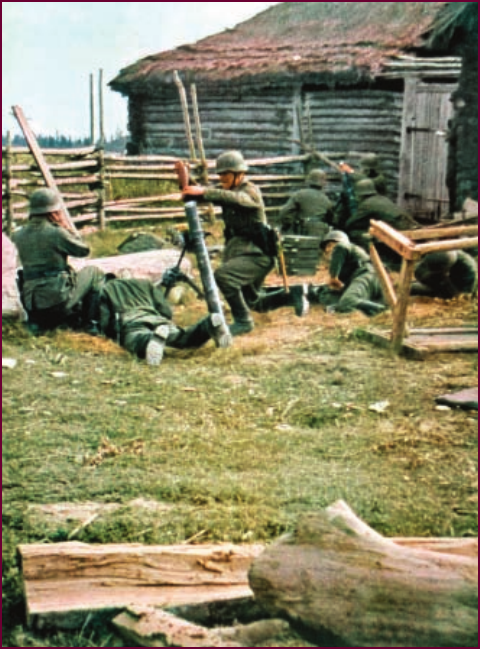

German Troops in the S oviet Union. At first, the German attack

on the Soviet Union was enormously successful, leading one German

general to remark in his diary, ‘‘It is probably no overstatement to say

that the Russian campaign has been won in the space of two weeks.’’ This

picture shows German troops firing on Soviet positions.

c

Artmedia/HIP/The Image Works

626 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

surrendered in Tunisia on May 13, 1943, the Allies crossed

the Mediterranean and carried the war to Italy. After taking

Sicily, Allied troops began the invasion of mainland Italy in

September. In the meantime, after the ouster and arrest of

Benito M ussolini, a new Italian government offered to

surrender to Allied forces. But Mussolini was liberated by

the Germans in a daring raid and then set up as the head of

a puppet German state in northern Italy while German

troops moved in and occupied much of Italy. The new

defensive lines established by the Germans in the hills

south of Rome were so effective that the Allied advance up

the Italian peninsula was a painstaking affair accompanied

by heavy casualties. Rome did not fall to the Allies until

J une 4, 1944. By that time, the Italian war had assumed a

secondary role anywa y as the Allies opened their long-

awaited ‘‘second front ’’ in western Europe.

Under the direction of the American general Dwight

D. Eisenhower (1890--1969), the Allies landed five assault

A

A

A

l

l

l

l

e

e

e

u

u

u

t

t

t

i

i

a

a

n

n

I

I

I

s

s

s

l

l

l

l

a

a

a

n

n

n

d

d

d

s

s

A

LA

S

K

A

M

MAN

N

N

N

N

N

M

M

N

CHU

KUO

M

(MA

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

NCH

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

URI

A)

)

)

A)

)

K

Ka

Ka

a

am

a

a

cha

a

a

a

a

a

a

tk

tka

tka

tk

tk

tk

t

a

a

a

a

a

tk

tk

tk

tk

t

a

a

a

a

IW

IWO

I

JIMA

O

O

O

O

O

MID

MID

WAY

W

HAW

HA

H

A

II

A

N

IS

IS

SL

I

AND

S

G

GU

GUA

UA

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

DAL

DA

CANAL

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

DA

TIN

IAN

A

OK

O

KI

KI

NAW

A

K

O

OK

OK

WA

W

A

WA

W

W

AW

W

W

AW

AW

ATT

TT

U

U

TU

S

o

l

omo

n

Isl

Isl

Is

I

and

a

s

Mar

ar

sha

h

sha

ll

ll

ll

I

Isl

Isl

and

and

s

s

s

S

S

Sa

ai

p

an

Gua

m

Gua

Bon

B

in Islands

in

n

n

i

in

Mariana Is

l

an

ds

Kur

Kur

ur

ile

ile

ile

Is

Is

lan

lan

n

d

d

ds

ds

land

Ryu

Ryu

yu

R

R

k

ku

ku

Isl

and

nd

d

d

s

s

s

R

R

R

R

Car

oli

li

n

ne

ne

e

Isl

Isl

Isl

Is

and

an

a

s

Sa

Sak

Sa

Sa

Sa

Sak

Sa

h

ha

hal

in

Sa

Sa

Sa

Sa

Sa

Paci

f

ic

O

cea

n

I

n

d

ia

n

O

cea

n

Cora

l

S

e

a

SO

VIET

U

NI

ON

IND

D

D

D

D

IA

D

D

D

D

D

BUR

MA

MA

MA

A

A

MA

A

MA

MA

BU

BUR

A

A

U

THA

THA

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

TH

A

A

A

I

I

I

ILA

I

I

I

ND

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

D

ND

D

FRE

N

N

NCH

H

NCH

H

N

H

N

H

N

N

H

N

N

N

N

H

H

H

N

H

N

N

N

H

H

H

N

N

H

H

H

H

N

NC

N

N

NC

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

NC

NC

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

FRE

FRE

CH

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

IN

INA

A

A

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

IN

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

IND

I

I

I

I

OC

DOC

A

U

S

TRALI

A

PH

P

H

PHI

PHI

I

H

H

PH

H

H

PH

PH

H

H

P

P

L

LIP

PIN

E

PH

P

H

PH

H

H

PH

H

PH

PH

H

H

P

P

P

P

SL

ISL

ISL

L

ISL

ISL

ISL

SL

IS

ISL

ISL

ISL

S

ISL

ISL

IS

ISL

SL

S

ISL

L

IS

IS

ISL

IS

S

ISL

ISL

L

S

S

IS

S

I

S

A

AND

A

A

S

ISL

IS

IS

IS

IS

IS

IS

I

IS

S

S

IS

IS

S

S

IS

IS

S

S

S

ISL

IS

IS

IS

S

IS

IS

I

IS

I

IS

I

I

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

KOR

KOR

OR

KOR

KOR

KO

KOR

KOR

KOR

KOR

R

KOR

KO

KOR

R

KOR

R

OR

O

KO

OR

O

KO

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

EA

EA

A

A

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

KOR

KOR

KOR

KO

R

KOR

KOR

OR

KOR

KOR

KO

R

R

KOR

OR

K

KO

KO

KO

KO

K

KO

O

O

O

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

MONGOLIA

C

HINA

CANADA

J

JAP

JAP

P

P

P

P

AP

P

AP

AP

P

P

AP

P

P

P

A

P

A

A

A

A

A

AN

AN

N

N

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

AP

P

AP

AP

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

MAL

A

A

A

AL

AL

AL

L

L

MAL

A

A

A

M

A

L

A

L

L

A

L

A

A

A

A

A

AY

YA

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

AL

A

A

A

AL

AL

AL

AL

L

A

A

L

L

A

L

L

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

ALAY

AL

L

L

L

L

L

A

AYA

L

L

L

L

L

ALAY

B

BOR

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

NEO

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

D

D

D

D

U

U

U

U

T

T

T

C

C

C

C

H

H

H

H

E

E

E

A

A

S

S

T

T

I

I

I

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

E

E

E

E

S

S

S

T

To

Tok

ky

ky

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

o

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

Naga

aga

ga

saki

i

saki

i

ki

ki

i

ki

ki

k

i

ki

k

ki

ki

k

i

k

k

ki

ki

k

s

i

ki

i

i

ki

i

i

ki

ki

ki

ki

ki

ki

i

ki

ki

ki

ki

ki

k

ki

ki

ki

i

i

ki

i

i

k

i

Hi

iro

Hi

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

Hi

i

sh

him

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

a

a

a

a

a

a

Hi

ir

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

Hi

i

sh

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

a

a

a

a

a

a

Chun

gkin

in

n

n

n

n

n

in

g

in

N

an

ji

n

g

Sing

in

Sin

S

S

Sin

Sin

Sing

in

Sin

Sing

S

S

Si

Sing

Sin

Sin

S

n

Sin

S

i

Sin

Sing

S

i

ng

Sin

i

apor

or

or

or

r

or

r

r

r

r

or

or

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

e

e

e

e

e

e

or

o

o

o

o

Si

S

S

S

Si

S

S

S

Si

Si

Si

S

Si

S

S

Si

S

S

S

S

Si

i

S

i

i

i

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

e

e

e

e

or

or

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

ng

ng

ng

n

n

ng

n

ng

ng

n

g

g

g

or

or

r

r

or

or

r

or

r

r

or

r

r

or

r

r

r

r

r

e

e

e

e

e

e

Hon

Hon

n

Hon

H

Hong

n

H

Hon

H

H

Hon

H

n

Hong

Hon

Hon

Hon

H

H

H

H

Hon

Hon

n

n

Hon

Hong

n

H

H

Hon

Hon

Hon

n

Hon

Hon

H

H

H

on

Kon

Kong

K

K

Kong

K

ong

K

K

K

K

K

Pea

Pear

ar

l

l

l

Harb

or

or

r

Anchorage

0

5

00 1,000 Miles

0 500 1

,00

0 1

,50

0 Kilo

m

me

et

et

e

e

ers

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

Allied powers and areas

under Allied control

Japanese Empire, 1937

Japanese conquests, 1937–1944

Japanese satellite areas, 1941

Farthest Japanese advance

Allied offensives, 1942–1945

Japanese offensives, 1942–1945

Main bombing routes

Naval battles

World War II: Asia and the Pacific

MAP 25.2 Wo rld War II in Asia and the Pacific. In 1937, Japan invaded northern China,

beginning its effort to create a ‘‘Great East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.’’ Further expansion led

the United States to end iron and oil sales to Japan. Deciding that war with the United States

was inevitable, Japan engineered a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

Q

Wh y was control of the islands in the western P acific of great importance both to the

Japanese and to the Allies?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www.cengage.com/history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

WORLD WAR II 627

divisions on the beaches of Normandy on June 6 in his-

tory’s greatest naval invasion. An initially indecisive

German response enabled the Allied forces to establish a

beachhead. Within three months, they had landed two

million men and a half-million vehicles that pushed in-

land and broke through German defensive lines.

After the breakout, Allied troops moved south and

east and liberated Paris by the end of August. By March

1945, they had crossed the Rhine River and advanced

deep into Germany. At the end of April 1945, Allied ar-

mies in northern Germany moved toward the Elbe River,

where they finally linked up with the Soviets. The Soviets

had come a long way since the Battle of Stalingrad in

1943. In the summer of 1943, German forces were

soundly defeated by the Soviets at the Battle of Kursk

(July 5--12), the greatest tank battle of World War II.

Soviet forces now began a relentless advance westward.

The Soviets had reoccupied Ukraine by the end of 1943

and lifted the siege of Leningrad and moved into the

Baltic states by the beginning of 1944. Advancing along a

northern front, Soviet troops occupied Warsaw in Janu-

ary 1945 and entered Berlin in April. Meanwhile, Soviet

troops along a southern front swept through Hungary,

Romania, and Bulgaria.

In January 1945, Hitler had moved into a bunker 55

feet under Berlin to direct the final stages of the war. In

his final political testament, Hitler, consistent to the end

in his rabid anti-Semitism, blamed the Jews for the war.

Hitler committed suicide on April 30, two days after

Mussolini had been shot by partisan Italian forces.

AGERMAN SOLDIER AT STALINGRAD

The Soviet victory at Stalingrad was a major turning

point in World War II. This excerpt comes from the

diary of a German soldier who fought and died in

the Battle of Stalingrad. His dreams of victory and

a return home with medals were soon dashed by the realities

of Soviet resistance.

Diary of a German Soldier

Today, after we’d had a bath, the company commander told us that if

our future operations are as successful, we’ll soon reach the Volga,

take Stalingrad, and then the war will inevitably soon be over. Perhaps

we’ll be home by Christmas.

July 29. The company commander says the Russian troops are

completely broken, and cannot hold out any longer. To reach the

Volga and take Stalingrad is not so difficult for us. The F

€

uhrer knows

where the Russians’ weak point is. Victory is not far away. ...

August 10. The F€uhrer’s orders were read out to us. He expects

victor y of us. We are all convinced that they can’t stop us.

August 12. This morning outstanding soldiers were presented with

decorations. ... W ill I really go back to Elsa without a decoration?

I believe that for Stalingrad the F

€

uhrer will decorate even me. ...

September 4. We are being sent northward along the front to-

ward Stalingrad. We marched all night and by dawn had reached

Voroponovo Station. We can already see the smoking town. It’s a

happy thought that the end of the war is getting nearer. That’s what

everyone is saying. ...

September 8. Two days of nonstop fighting. The Russians are

defending themselves with insane stubbornness. Our regiment has

lost many men. ...

September 16. Our battalion, plus tanks, is attacking the [grain

storage] elevator, from which smoke is pouring---the grain in it is

burning; the Russians seem to have set light to it themselves. Barba-

rism. The battalion is suffering heavy losses. ...

October 10. The Russians are so close to us that our planes

cannot bomb them. We are preparing for a decisive attack. The

F

€

uhrer has ordered the whole of Stalingrad to be taken as rapidly as

possible. ...

October 22. Our regiment has failed to break into the factory.

We have lost many men; ever y time you move you have to jump

over bodies. ...

November 10. A letter from Elsa today. Everyone expects us

home for Christmas. In Germany everyone believes we already hold

Stalingrad. How wrong they are. If they could only see what Stalin-

grad has done to our army. ...

November 21. The Russians have gone over to the offensive

along the whole front. Fierce fighting is going on. So, there it is---the

Volga, victory, and soon home to our families! We shall obviously

be seeing them next in the other world.

November 29. We are encircled. It was announced this morning

that the F

€

uhrer has said: ‘‘The army can trust me to do everything

necessary to ensure supplies and rapidly break the encirclement.’’

December 3. We are on hunger rations and waiting for the res-

cue that the F

€

uhrer promised. ...

December 14. Everybody is racked with hunger. Frozen potatoes

are the best meal, but to get them out of the ice-covered ground

under fire from Russian bullets is not so easy. ...

December 26. The horses have already been eaten. I would eat a

cat; they say its meat is also tasty. The soldiers look like corpses or

lunatics, looking for something to put in their mouths. They no

longer take cover from Russian shells; they haven’t the strength to

walk, run away, and hide. A curse on this war!

Q

What did this soldier believe about the F

€

uhrer? Why?

What was the source of his information? Why is the battle for

Stalingrad considered a major turning point in World War II?

628 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

On May 7, German commanders surrendered. The war in

Europe was over.

Allied war plans for Asia had originally called for a

massive military advance on the Japanese home islands

through China, making full use of the latent strength of

Chiang Kai-shek’s armed forces. By 1943, however, Pres-

ident Roosevelt had lost confidence in the ability of

Chiang Kai-shek’s government to play a positive role in

Allied operations and had turned to a ‘‘Pacific strategy’’

based on a gradual advance by U.S. military forces across

the Pacific Ocean. Beginning in 1943, American forces

had gone on the offensive and proceeded, slowly at times,

across the Pacific. The Americans took an increasing toll

of enemy resources, especially at sea and in the air. As

Allied military power drew inexorably closer to the main

Japanese islands in the first months of 1945, President

Harry Truman, who had succeeded to the presidency on

the death of Franklin Roosevelt in April, decided to use

atomic weapons to bring the war to an end without the

necessity of an Allied invasion of the Japanese homeland.

The first bomb was dropped on the city of Hiroshima on

August 6. Three days later, a second bomb was dropped

on Nagasaki. Japan surrendered unconditionally on

August 14. World War II was finally over.

The New Order

Q

Focus Question: What was the nature of the new

orders that Germany and Japan attempted to establish

in the territories they occupied?

The initial victories of the Germans and the Japanese had

given them the opportunity to restructure society in

Europe and Asia. Both followed policies of ruthless

domination of their subject peoples.

The New Order in Europe

In 1942, the Nazi empire stretched across continental

Europe from the English Channel in the west to the

outskirts of Moscow in the east. Nazi-occupied Europe

was largely organized in one of two ways. Some areas,

such as western Poland, were directly annexed by Nazi

Germany and made into German provinces. Most of

occupied Europe was administered by German military or

civilian officials, combined with different degrees of in-

direct control from collaborationist regimes.

Because the conquered lands in the east contained the

living space for German expansion and were, in Nazi eyes,

populated by racially inferior Slavic peoples, Nazi ad-

ministration there was considerably more ruthless. Soon

after the conquest of Poland, Heinrich Himmler, the

leader of the SS, was put in charge of German resettlement

plans in the east. Himmler’s task was to evacuate the in-

ferior Slavic peoples and replace them with Germans, a

policy first applied to the new German provinces created

from the lands of western Poland. One million Poles were

uprooted and dumped in southern Poland. Hundreds of

thousands of ethnic Germans (descendants of Germans

who had migrated years earlier from Germany to different

parts of southern and eastern Europe) were encouraged to

colonize the designated areas in Poland. By 1942, two

million ethnic Germans had been settled in Poland.

Labor shortages in Germany led to a policy of

ruthless mobilization of foreign labor for Germany. In

1942, a special office was created to recruit labor for

German farms and industries. By the summer of 1944,

seven million foreign workers were laboring in Germany

where they constituted 20 percent of the labor force. At

the same time, another seven million workers were sup-

plying forced labor in their own countries on farms, in

industries, and even in military camps. The brutality of

Germany’s recruitment policies often led more and more

people to resist the Nazi occupation forces.

The Holocaust

No aspect of the Nazi new order was more terrifying than

the deliberate attempt to exterminate the Jews of E urope.

CHRONOLOGY

The Course of World War II

Germany and the Soviet Union divide

Poland

September 28, 1939

Blitzkrieg against Denmark and Norway April 1940

Blitzkrieg against Belgium, Netherlands,

and France

May 1940

France surrenders June 22, 1940

Battle of Britain Fall 1940

Nazi seizure of Yugoslavia and Greece April 1941

Germany invades the Soviet Union June 22, 1941

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor December 7, 1941

Battle of the Coral Sea May 7--8, 1942

Battle of Midway Island June 4, 1942

Allied invasion of North Africa November 1942

German surrender at Stalingrad February 2, 1943

Axis forces surrender in North Africa May 1943

Battle of Kursk July 5--12, 1943

Invasion of mainland Italy September 1943

Allied invasion of France June 6, 1944

Hitler commits suicide April 30, 1945

Germany surrenders May 7, 1945

Atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima August 6, 1945

Japan surrenders August 14, 1945

T

HE NEW ORDER 629

Racial struggle was a key element in Hitler’s ideology and

meant to him a clearly defined conflict of opposites: the

Aryans, creators of human cultural development, against

the Jews, parasites who were trying to destroy the Aryans.

Himmler and the SS organization closely shared Hitler’s

racial ideology. The SS was given responsibility for what the

N azis called their Final Solution to the ‘‘Jewish problem’’---

annihilation of the Jews. After the defeat of Poland, the SS

ordered special strike forces (Einsatzgruppen) to round up

all P olish Jews and c oncentrate them in ghettos established

in a number of P olish cities.

In June 1941, the Einsatzgruppen were given new

responsibilities as mobile killing units. These SS death

squads followed the regular army’s advance into Russia.

Their job was to round up Jews in their villages, execute

them, and bury them in mass graves, often giant pits dug

by the victims themselves before they were shot. But the

constant killing led to morale problems among the SS

executioners. During a visit to Minsk in the Soviet Union,

Himmler tried to build morale by pointing out that he

‘‘would not like it if Germans did such a thing gladly. But

their conscience was in no way impaired, for they were

soldiers who had to carry out every order uncondition-

ally. He alone had responsibility before God and Hitler

for everything that was happening.’’

6

Although it has been estimated that as many as one

million Jews were killed by the Einsatzgruppen, this ap-

proach to solving the Jewish problem was soon perceived

as inadequate. Instead, the Nazis opted for the systematic

annihilation of the European Jewish population in spe-

cially built death camps. Jews from countries occupied by

Germany (or sympathetic to Germany) were rounded up,

packed like cattle into freight trains, and shipped to

Poland, where six extermination centers were built to

dispose of them. The largest and most famous was

Auschwitz-Birkenau. Medical technicians chose Zyklon B

(the commercial name for hydrogen cyanide) as the most

effective gas for quickly killing large numbers of people in

gas chambers designed to look like ‘‘shower rooms’’ to

facilitate the cooperation of the victims. After gassing, the

corpses were burned in specially built crematoria.

The death camps were in operation by the spring of

1942; by the summer, Jews were also being shipped from

France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Even as the Allies

were making significant advances in 1944, Jews were

being shipped from Greece and Hungary. A harrowing

experience awaited the Jews when they arrived at one of

the six death camps. Rudolf H

€

oss, commandant at

Auschwitz-Birkenau, described it:

We had two SS doctors on duty at Auschwitz to examine the

incoming transports of prisoners. The prisoners would be

marched by one of the doctors who would make spot deci-

sions as they walked by. Those who were fit for work were

sent into the camp. Others were sent immediately to the ex-

termination plants. Children of tender years were invariably

exterminated since by reason of their youth they were unable

to work. ... At Auschwitz we endeavored to fool the victims

into thinking that they were to go through a delousing pro-

cess. Of course, frequently they realized our true intentions

and we sometimes had riots and difficulties due to that fact.

7

About 30 percent of the arrivals at Auschwitz were sent to

a labor camp; the remainder went to the gas chambers

(see the box on p. 633). After they had been gassed, the

bodies were burned in the crematoria. The victims’ goods

and even their bodies were used for economic gain.

Female hair was cut off, collected, and turned into cloth

The Ho locaust: Activities of t he Einsatzgruppen. The mobile

killing units known as the Einsatzgruppen were active during the first

phase of mass killings of the Holocaust. This picture shows the execution

of a Jew by a member of one of these SS killing squads. Onlookers include

members of the German army, the German Labor Service, and even

Hitler Youth. When it became apparent that this method of killing was

inefficient, it was replaced by the death camps.

Library of Congress (2391, folder 401)

630 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

or used to stuff mattresses. The Germans killed between

five and six million Jews, more than three million of them

in the death camps. Virtually 90 percent of the Jewish

populations of Poland, the Baltic countries, and Germany

were exterminated.

The Nazis were also responsible for another

Holocaust, the death by shooting, starvation, or over-

work of at least another 9 to 10 million people. Because

the Nazis considered the Gypsies of Europe a race con-

taining alien blood (like the Jews), they were systemati-

cally rounded up for extermination. About 40 percent of

Europe’s one million Gypsies were killed in the death

camps. The leading elements of the ‘‘subhuman’’ Slavic

peoples---the clergy, intelligentsia, civil leaders, judges,

and lawyers---were arrested and deliberately killed. Prob-

ably an additional four million Poles, Ukrainians, and

Byelorussians lost their lives as slave laborers for Nazi

Germany. Finally, at least three million Soviet prisoners of

war, and probably more, were killed in captivity.

The New Order in Asia

Once Japan’s takeover was completed, Japanese war policy

in the occupied areas in Asia became essentially defensive,

as Japan hoped to use its new possessions to meet

its needs for raw materials, such as tin, oil, and rubber,

as well as to serve as an outlet for Japanese manufactured

goods. To provide a structure for the arrangement,

Japanese leaders set up the Greater East Asia Co-

Prosperity Sphere as a self-sufficient community designed

to provide mutual benefits to the occupied areas and the

home country.

The Japanese conquest of Southeast Asia had been

accomplished under the slogan ‘‘Asia for the Asians.’’

Japanese officials in occupied territories quickly promised

that independent governments would be established un-

der Japanese tutelage. Such governments were eventually

established in Burma, the Dutch East Indies, Vietnam,

and the Philippines.

In fact, however, real power rested with the Japanese

military authorities in each territory, and the local Japa-

nese military command was directly subordinated to the

army general staff in Tokyo. The economic resources of

the colonies were exploited for the benefit of the Japanese

war machine, while natives were recruited to serve in local

military units or conscripted to work on public works

projects. In some cases, the people living in the occupied

areas were subjected to severe hardships. In Indochina,

for example, forced requisitions of rice by the local

Japanese authorities for shipment abroad created a food

shortage that caused the starvation of more than a million

Vietnamese in 1944 and 1945.

At first, many Southeast Asian nationalists took

Japanese promises at face value and agreed to cooperate

with their new masters. But as the exploitative nature of

Japanese occupation policies became clear, sentiment

turned against the new order. Japanese officials some-

times unwittingly provoked such attitudes by their arro-

gance and contempt for local customs.

Japanese military planners had little respect for their

subject peoples and viewed the Geneva Convention on

the laws of war as little more than a fabrication of

Western countries to tie the hands of their adversaries. In

conquering northern and central China, the Japanese

freely used poison gas and biological weapons, which

caused the deaths of millions of Chinese citizens. The

Japanese occupation of the onetime Chinese capital of

Nanjing was especially brutal. In the notorious ‘‘Nanjing

Incident,’’ they spent several days killing, raping, and

looting the local population.

Japanese soldiers also treated Koreans savagely. Al-

most 800,000 Koreans were sent overseas, most of them as

forced laborers, to Japan. Tens of thousands of women

from Korea and the Philippines were forced to be

‘‘comfort women’’ (prostitutes) for Japanese troops. In

construction projects to help their war effort, the Japanese

also made extensive use of labor forces composed of

both prisoners of war and local peoples. In building the

Burma-Thailand railway in 1943, for example, the

Japanese used 61,000 Australian, British, and Dutch

prisoners of war and almost 300,000 workers from

Burma, Malaya, Thailand, and the Dutch East Indies. By

the time the railway was completed, 12,000 Allied pris-

oners of war and 90,000 native workers had died as a

result of the inadequate diet and appalling work con-

ditions in an unhealthy climate.

The Home Front

Q

Focus Question: What were conditions like on the

home front for the major belligerents in World War II?

World War II was even more of a total war than World War I.

Fighting was much more widespread and cover ed most of

the world. The number of civilians killed was far higher.

Mobilizing the People: Three Examples

The initial defeats of the Soviet Union led to drastic

emergency mobilization measures that affected the civil-

ian population. Leningrad, for example, experienced nine

hundred days of siege, during which its inhabitants became

so desperate for food that they ate dogs, cats, and mice.

THE HOME FRO NT 631

As the German army made its rapid advance into Soviet

territory, the factories in the western part of the Soviet

Union were dismantled and shipped to the interior---to

the Urals, western Siberia, and the Volga region. Machines

were set down on the bare earth, and walls went up

around them as workers began their work.

Stalin calle d the widespread military and industrial

mobilization of the nation a ‘‘battle of machines,’’ and

the Soviets won, producing 78,000 tanks and 98,000

artillery pieces. In 1943, fully 55 percent of Soviet na-

tional income wen t for war mat

eriel, compared to 15

percent in 1940 (see the comparative essay ‘‘Paths to

Modernization’’ on p. 634).

Soviet women played a major role in the war effort.

Women and girls were enlisted for work in industries,

mines, and railroads. Overall the number of women

FILM & HISTORY

E

UROPA,EUROPA (1990)

Directed by Agnieszka Holland, Europa, Europa (known as Hitler-

junge Salomon [Hitler Youth Salomon] in Germany) is the harrow-

ing story of one Jewish boy’s escape from the horrors of Nazi

persecution. It is based on the memoirs of Salomon Perel, a German

Jew of Polish background who survived by pretending to be a pure

Aryan. The film begins in 1938 during Kristallnacht when the family

of Solly (Perel’s nickname) is attacked in their hometown of Peine,

Germany. Solly’s sister is killed, and the family moves back to

Poland. When the Nazis invade Poland, Solly (Marco Hofschneider)

and his brother are sent east, but the brothers become separated and

Solly is placed in a Soviet orphanage in Grodno in the eastern part

of Poland occupied by the Soviets.

For two years, Solly becomes a dedicated Communist youth,

but when the Germans invade in 1941, he falls into their hands and

quickly assumes a new identity in order to survive. He becomes

Josef ‘‘Jupp’’ Peters, supposedly the son of German parents from

Latvia. Fluent in both Russian and German, Solly/Jupp becomes a

translator for the German forces. After an unintended act of bra-

vado, he is rewarded by being sent to a Hitler Youth school where

he lives in fear of being exposed as a Jew because of his circumcised

penis. He manages to survive the downfall of Nazi Germany and at

the end of the war makes his way with his brother, who has also

survived, to Palestine. Throughout much of the movie, Solly/Jupp

lives in constant fear that his true identity as a Jew will be recog-

nized, but his luck, charm, and resourcefulness enable him to sur-

vive a series of extraordinary events.

Although there is no way of knowing if each detail of this

movie is historically accurate (and some are clearly inaccurate, such

as a bombing run by a plane that was not developed until after the

war), overall the story has the ring of truth. The fanaticism of both

the Soviet and the Nazi officials who indoctrinate young people

seems real. The scene in the Hitler Youth school on how to identify

a Jew is realistic, even when it is made ironic by the instructor’s

choice of Solly/Jupp to demonstrate the characteristics of a true

Aryan. The movie also realistically portrays the fearful world in

which Jews had to live under the Nazis before the war and the hor-

rible conditions of the Jewish ghettos in Polish cities during the war.

The film shows how people had to fight for their survival in a world

of ideological madness, when Jews were killed simply for being Jews.

The attitudes of the German soldiers also seem real. Many are

shown following orders and killing Jews based on the beliefs in

which they have been indoctrinated. But the movie also portrays

some German soldiers whose humanity did not allow them to kill

Jews. One homosexual soldier discovers that Solly/Jupp is a Jew

when he tries---unsuccessfully---to have sex with him. The soldier

then becomes the boy’s protector until he himself is killed in battle.

Many movies have been made about the horrible experiences of

Jews during World War II, but this one is quite different from most

of them. It might never have been made except for the fact that Salo-

mon Perel, who was told by his brother not to tell his story because

no one would believe it, was inspired to write his memoirs after a

1985 reunion with his former Hitler Youth group leader. This pas-

sionate and intelligent film is ultimately a result of that encounter.

Salomon Perel/Josef Peters (Marco Hofschneider) as a Hitler

Youth member

Les Films Du Losange/CCC Filmkunst/The Kobal Collection

632 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

working in industry increased almost 60 percent. Soviet

women were also expected to dig antitank ditches

and work as air raid wardens. In addition, the Soviet

Union was the only country in World War II to use

women as combatants. Soviet women functioned as

snipers and as crews in bomber squadrons.

In August 1914, Germans had enthusiastically

cheered their soldiers marching off to war; in September

1939, the streets were quiet. Many Germans were apa-

thetic or, even worse for the Nazi regime, had a fore-

boding of disaster. Hitler was very aware of the

importance of the home front. He believed that the col-

lapse of the home front in World War I had caused

Germany’s defeat. To avoid a repetition of that experience,

he adopted economic policies that may indeed have cost

Germany the war.

To maintain the morale of the home front during

the first two years of the war, Hitler refused to cut

production of consumer goods or increas e the

production of armaments. After German defeats on the

Russian front and the American entry into the war,

however, th e situati on changed. Early in 1942, Hitler

finally ordered a massive increase in armaments pro-

duction and the siz e of the army. Hitler’s architect, Al-

bert Speer, was made minister for armaments and

munitions in 1942. By eliminating waste and rational-

izing procedures. Spee r was able to triple the production

of armaments bet ween 1942 and 1943, desp ite the in-

tense Allied air raids. Speer’s urgent plea for a total

mobilization of resources for the war effort went un-

heeded, however. Hitler, fearful of civilian morale

problems that would undermine the home front, ref used

any dramati c cuts in t he production of consumer goods.

A total mobilization of the economy was not im-

plemented until 1944, but by that time, it was too late.

The war produced a reversal in Nazi attitudes toward

women. Nazi resistance to female employment declined

as the war progressed and more and more men were

THE HOLOCAUST:THE CAMP COMMANDANT AND THE C AMP VICTIMS

The systematic annihilation of millions of men,

women, and children in extermination camps

makes the Holocaust one of the most horrifying

events in history. The first document is taken from

an account by Rudolf H

€

oss, commandant of the extermination

camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. In the second document, a French

doctor explains what happened at one of the crematoria de-

scribed by H

€

oss.

Commandant H

€

oss Describes the Equipment

The two large crematoria, Nos. I and II, were built during the winter

of 1942--43. ... Each ...could cremate c. 2,000 corpses within

twenty-four hours. ... Crematoria I and II both had underground

undressing and gassing rooms which could be completely ventilated.

The corpses were brought up to the ovens on the floor above by lift.

The gas chambers could hold c. 3,000 people.

The firm of Topf had calculated that the two smaller cremato-

ria, III and IV, would each be able to cremate 1,500 corpses within

twenty-four hours. However, owing to the wartime shortage of

materials, the builders were obliged to economize, and so the

undressing rooms and gassing rooms were built above ground and

the ovens were of a less solid construction. But it soon became ap-

parent that the flimsy construction of these two four-retort ovens

was not up to the demands made on it. No. III ceased operating al-

together after a short time and later was no longer used. No. IV had

to be repeatedly shut down since after a short period in operation

of 4--6 weeks, the ovens and chimneys had burnt out. The victims

of the gassing were mainly burnt in pits behind crematorium IV.

The largest number of people gassed and cremated within

twenty-four hours was somewhat over 9,000.

A French Doctor Describes the Victims

It is mid-day, when a long line of women, children, and old people

enter the yard. The senior official in charge ...climbs on a bench to

tell them that they are going to have a bath and that afterward they

will get a drink of hot coffee. They all undress in the yard. ... The

doors are opened and an indescribable jostling begins. The first peo-

ple to enter the gas chamber begin to draw back. They sense the

death which awaits them. The SS men put an end to this pushing

and shoving wi th blows from their rifle butts beating the heads of

the horrified women who are desperately hugging their children.

The massive oak double doors are shut. For two endless minutes

one can hear banging on the walls and screams which are no longer

human. And then---not a sound. Five minutes later the doors are

opened. The corpses, squashed together and distorted, fall out like a

waterfall. ... The bodies, which are still warm, pass through the

hands of the hairdresser, who cuts their hair, and the dentist, who

pulls out their gold teeth. ... One more transport has just been pro-

cessed through No. IV crematorium.

Q

What ‘‘equipment’’ does H

€

oss describe? What process

does the French doctor describe? Is there any sympathy for the

victims in either account? Why or why not? How could such a

horrifying process have been allowed to occur? Who was held

responsible after the war? Was this sufficient?

THE HOME FRO NT 633

called up for military service. Nazi magazines now pro-

claimed, ‘‘We see the woman as the eternal mother of our

people, but also as the working and fighting comrade of

the man.’’

8

But the number of women working in in-

dustry, agriculture, commerce, and domestic service in-

creased only slightly. The total number of employed

women in September 1944 was 14.9 million, compared

with 14.6 million in May 1939. Many women, especially

those of the middle class, resisted regular employment,

particularly in factories.

Wartime Japan was a highly mobilized society. To

guarantee its control over all national resources, the gov-

ernment set up a planning board to control prices, wages,

the utilization of labor, and the allocation of resources.

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

P

ATHS TO MODERNIZATION

To the casual observer, the most important feature

of the first half of the twentieth century was the

rise of a virulent form of competitive nationalism

that began in Europe and ultimately descended

into the cauldron of two destructive world wars. Behind the

scenes, however, the leading countries were also engaging in

another form of competition over the most effective path to

modernization.

The traditional approach, fostered by an independent urban mer-

chant class, had been adopted by Great Britain, France, and the

United States and led to the emergence of democratic societies on

the capitalist model. A second approach, adopted in the late nine-

teenth century by imperial Germany and Meiji Japan, was carried

out by traditional elites in the absence of a strong independent

bourgeois class. They relied on strong government intervention to

promote the growth of national wealth and power and led ultimately

to the formation of fascist and militarist regimes during the depres-

sion years of the early 1930s.

The third approach, selected by Vladimir Lenin after the

Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, was designed to carry out an indus-

trial revolution without going through an intermediate capitalist

stage. Guided by the Communist Party in the almost total absence

of an urban middle class, this approach envisaged the creation of an

advanced industrial society by destroying the concept of private

property. Although Lenin’s plans ultimately called for the ‘‘withering

of the state,’’ the party adopted totalitarian methods to eliminate en-

emies of the revolution and carry out the changes needed to create a

future classless utopia.

How did these various approaches contribute to the series of

crises that afflicted the world during the first half of the twentieth

century? The democratic-capitalist approach proved to be a consid-

erable success in an economic sense, leading to the creation of ad-

vanced economies that could produce manufactured goods at a rate

never seen before. Societies just beginning to undergo their own

industrial revolutions tried to imitate the success of the capitalist

nations by carrying out their own ‘‘revolutions from above’’ in

Germany and Japan. But the Great Depression and competition over

resources and markets soon led to an intense rivalry between the

established capitalist states and their ambitious late arrivals, a rivalry

that ultimately erupted into global conflict.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, imperial Russia

appeared ready to launch its own bid to join the ranks of the indus-

trialized nations. But that effort was derailed by its entry into World

War I, and before that conflict had come to an end, the Bolsheviks

were in power. Isolated from the capitalist marketplace by mutual

consent, the Soviet Union was able to avoid being dragged into the

Great Depression but, despite Stalin’s efforts, was unsuccessful in

staying out of the ‘‘battle of imperialists’’ that followed at the end of

the 1930s. As World War II came to an end, the stage was set for a

battle of the victors---the United States and the Soviet Union---over

political and ideological supremacy.

Q

What were the three major paths to modernization in the

first half of the twentieth century, and why did they lead to

conflict?

The Soviet Path to Modernization. One aspect of the Soviet effort

to create an advanced industrial society was to collectivize agriculture,

which included a rapid mechanization of food production. Seen here are

peasants watching a new tractor at work.

c

Bettmann/CORBIS

634 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

Traditional habits of obedience and hierarchy, buttressed

by the concept of imperial divinity, were emphasized to

encourage citizens to sacrifice their resources, and some-

times their lives, for the national cause. The system cul-

minated in the final years of the war, when young Japanese

were encouraged to volunteer en masse to serve as pilots

in the suicide missions (known as kamikaze, ‘‘divine

wind’’) against U.S. battleships.

Women’s rights too were to be sacrificed to the

greater national cause. Already by 1937, Japanese women

were being exhorted to fulfill their patriotic duty by

bearing more children and by espousing the slogans of the

Greater Japanese Women’s Association. Japan was ex-

tremely reluctant to mobilize women on behalf of the war

effort, however. General Hideki Tojo, prime minister

from 1941 to 1944, opposed female employment, arguing

that ‘‘the weakening of the family system would be the

weakening of the nation. ... We are able to do our duties

only because we have wives and mothers at home.’’

9

Female employment increased during the war, but only in

areas where women traditionally worked, such as the

textile industry and farming. Instead of using women to

meet labor shortages, the Japanese government brought

in Korean and Chinese laborers.

The Frontline Civilians:

The Bombing of Cities

Bombing was used in World War II against a variety of

targets, including military targets, enemy troops, and

civilian populations. The bombing of civilians made

World War II as devastating for civilians as for frontline

soldiers. A small number of bombing raids in the last year

of World War I had given rise to the argument that public

outcry over the bombing of civilian populations would be

an effective way to coerce governments into making peace.

Consequently, European air forces began to develop long-

range bombers in the 1930s.

The first sustained use of civilian bombing contra-

dicted the theory. Beginning in early September 1940, the

German Luftwaffe subjected London and many other

British cities and towns to nightly air raids, making the

Blitz (as the British called the German air raids) a na-

tional experience. Londoners took the first heavy blows

but kept up their morale, setting the standard for the rest

of the British population (see the comparative illustration

on p. 636).

The British failed to learn from their own experi-

ence, however; Prime Minister Winston Churchill and

his adv isers believed that destroy ing German commu-

nities would break civ ilian morale and bring v ictory.

Major bombing raids began in 1942. On May 31, 1942,

Cologne became the first German city to be subjected to

an attack by a thousand bombers. Bombing raids added

an element of terror to circumstances a lready made

difficult by growing shortages of food, clothing, and

fuel. Germans especially feared incendiar y bombs,

which ignited firestorms that swept destructive paths

through the cities. The ferocious bombing of Dresden

from February 13 to 1 5, 1945, set off a f irestorm that

mayhavekilledasmanyas35,000inhabitantsand

refugees.

Germany suffered enormously from the Allied

bombi ng ra ids. Millions of buildings were destroyed,

and possibly half a million civilians died from the raids.

Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that Allied bombi ng

sapped the morale of the German people. Instead

Germans, whether pro-Nazi or anti-Nazi, fought on

stubbornly, often driven simply by a desire to live. Nor

did the bo mbing destroy Germany’s industrial ca pacit y.

The Allied strategic bo mbing survey revealed t hat the

production of war mat

eriel actually increased between

1942 and 1944.

In Japan, the bombing of civilians reached a hor-

rendous new level with the use of the first atomic bomb.

Attacks on Japanese cities by the new American B-29

Superfortresses, the biggest bombers of the war, had be-

gun on November 24, 1944. By the summer of 1945,

many of Japan’s industries had been destroyed, along w ith

one-fourth of its dwellings. After the Japanese govern-

ment decreed the mobilization of all people between the

ages of thirteen and sixty into the so-called People’s

Volunteer Corps, President Truman and his advisers de-

cided that Japanese fanaticism might mean a million

American casualties, and Truman decided to drop the

newly developed atomic bomb on Hiroshima and

Nagasaki. The destruction was incredible. Of 76,000

buildings near the hypocenter of the explosion in Hi-

roshima, 70,000 were flattened, and 140,000 of the city’s

400,000 inhabitants had died by the end of 1945. Over the

next five years, another 50,000 perished from the effects

of radiation. The dropping of the atomic bomb on

Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, announced the dawn of the

nuclear age.

Aftermath of the War

Q

Focus Questions: What were the costs of World War II?

How did the Allies’ visions of the postwar differ , and

how did these differences contribute to the emergence

of the Cold War?

World War II was the most destructive war in history.

Much had been at stake. Nazi Germany followed a

worldview based on racial extermination and the

AFTERMATH OF THE WAR 635