Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

enslavement of millions in order to create an Aryan racial

empire. The Japanese, fueled by extreme nationalist ide-

als, also pursued dreams of empire in Asia that led to

mass murder and untold devastation. Fighting the Axis

Powers in World War II required the mobilization of

millions of ordinary men and women in the Allied

countries who struggled to preserve a different way of life.

As Winston Churchill once put it, ‘‘War is horrible, but

slavery is worse.’’

The Costs of World War II

The costs of World War II were enormous. At least 21

million soldiers died. Civilian deaths were even greater

and are now estimated at around 40 million. Of these,

more than 28 million were Ru ssian and Chinese. The

Soviet Union experienced the greatest losses: 10 million

soldiers and 19 million civilians. In 1945, millions of

people around the world faced s tarvation: in Europe,

100 million people depended on food relief of some

kind.

Millions of people had also been uprooted by the

wa r and became ‘‘displaced persons.’’ Europe alone may

have had 30 million displaced persons, many of whom

found it hard to return home. In Asia, millions of

Japanese were returned from the former Japanese em-

pire to Japan, while thousands of Korean f orced laborers

ret urned to Korea.

Everywhere cities lay in ruins. In Europe, the physical

devastation was especially bad in eastern and southeastern

Europe as well as in the cities of western and central

Europe. In Asia, China had experienced extensive devas-

tation from eight years of conflict. So too had the

Philippines, while large sections of the major cities in

Japan had been destroyed in air raids. The total monetary

cost of the war has been estimated at $4 trillion.

COMPARATIVE ILLUSTRATION

The Bom bing o f Civilia ns— East and West. World War II was the most

destructive war in world history, not only for frontline soldiers but for civilians at

home as well. The most devastating bombing of civilians came near the end of

World War II when the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At the left is a view of Hiroshima after the bombing that shows the

incredible devastation produced by the atomic bomb. The picture at the right shows a street in

Clydebank, near Glasgow in Scotland, the day after the city was bombed by the Germans in

March 1941. Only 7 of the city’s 12,000 houses were left undamaged; 35,000 of the 47,000

inhabitants became homeless overnight.

Q

What was the rationale for bombing civilian populations? Did such bombing achieve

its goal?

c

J.R. Eyeman/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

c

Keyston/Getty Images

636 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

The economies of most belligerents, with the exception of

the United States, were left on the brink of disaster.

The Allied War Conferences

Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill, the leaders of the Big

Three of t he Grand Alliance, met at Tehran, the capital

of Iran, in November 1943 to decide the future course

of the war. Stalin and Roosevelt argued successfully for

an American-British invasion of the Continent through

France, which they scheduled for the spring of 1944.

This meant that Soviet and British-American forces

would meet in defeated Germany along a north-south

dividing line and that Soviet forces would liberate

eastern Europe . The Allies also agreed to a partition of

postwar Germany.

Ams

ter

r

er

e

r

e

e

r

da

dam

a

a

dam

da

am

a

a

a

erdam

ms

te

e

e

e

e

e

Brusse

ls

ls

ls

ls

ls

ls

ls

s

ls

s

ls

M

ila

n

B

ern

Munich

Mun

Be

l

gra

de

Tir

Tir

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

Tir

ana

an

an

an

an

an

a

an

an

an

n

a

ir

r

r

r

ir

r

r

r

r

r

n

an

an

an

an

an

an

an

a

S

o

fi

a

Bucha

r

est

Ist

It

Ist

anb

b

anb

anb

l

ul

ul

ul

Bu

d

apest

Vie

i

e

i

i

i

ie

nna

ie

ie

V

V

V

P

ra

g

ue

War

saw

w

B

rest

G

Gda

Gda

nsk

nsk

k

nsk

(Da

a

a

nzi

i

nzi

nzi

nzi

i

i

i

i

nzi

nzi

zi

n

n

nzi

nzi

i

i

nzi

i

i

n

i

n

i

i

nzi

zi

zi

n

n

z

g)g)

g

g

)

g)

g

g

g

g

g)

g)

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

an

nzi

nzi

zi

i

i

i

zi

nzi

nzi

nzi

i

i

i

nz

nzi

nzi

i

i

i

zi

z

g)

g

g)

g)

g)

g)

g

g

g

)

)

g

g

g

C

C

C

C

C

Cop

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

enh

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

ag

ag

g

ageage

ag

ag

g

a

a

a

a

a

a

n

n

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

ag

ag

ag

age

ag

ag

a

a

a

n

Oslo

lo

St

to

Sto

Sto

Sto

Sto

t

Sto

Sto

Sto

St

Sto

t

St

ck

ckh

kh

kh

ol

olm

St

to

Sto

Sto

Sto

t

to

Sto

Sto

S

Helsi

n

ki

L

enin

g

ra

d

Rome

R

Bre

men

B

Ber

lin

n

n

n

n

n

n

B

B

B

B

Ath

Ath

Ath

At

A

Ath

Ath

Ath

Ath

Ath

At

A

A

t

A

t

t

h

h

ens

ens

ens

ens

ens

ens

ens

ens

ens

e

ens

s

e

Ath

Ath

Ath

Ath

Ath

At

Ath

Ath

Ath

A

t

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

Cor

r

s

sic

sic

ic

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

a

a

a

a

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

a

(Fr

Fr

r

.)

)

.

)

Sar

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

d

d

din

d

din

n

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

ia

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

(I

I

I

It

It

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

.

)

)

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

U.S.

Zon

Zon

on

e

e

B

ritish Zone

Fren

ch

ch

ch

ch

Zo

n

e

Frenc

h

Zon

Zon

Z

Zo

Zo

Zone

Zone

Zo

o

o

Zone

U

.

S

.

Zo

n

e

U

.

S

.

British

h

Zone

Soviet

Zone

Zone

Soviet

Z

one

To U

SS

R

,

1940

T

o USSR

,

1940

T

o USSR,

1940

From Po

l

an

d,

1

940–1947

Fr

Fr

ro

rom

ro

Fr

r

Czechos

lova

a

a

a

a

kia,

Fro

a

1

940–1947

F

rom Romania,

1940

1940

1

1

19

1940

–1947

1940

Incorporated into

Poland

,

194

5

I

In

Inco

r

p

orate

d

i

nt

o

o

U

SSR

,

194

5

From

om

om

om

m

m

m

m

om

Finl

a

n

n

nd,

an

1940

–

1

1

195

1

1

1

6

–1

1947

9

19

4

6

1944

194

5

1

947

1948

1

9

4

9

1

9

47

DE

N

N

NM

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

ARK

M

M

MM

M

M

M

M

M

M

SO

VIE

T

U

NION

NO

RWA

Y

S

WEDEN

F

INL

A

N

D

EA

ST

GERMAN

Y

WE

ST

W

GERMAN

Y

R

ER

AUSTRI

A

A

A

TR

UST

A

HUNGARY

G

R

O

MANIA

BUL

G

ARI

A

YU

GOS

LAVI

A

AL

AL

AL

A

B

BA

A

A

N

N

N

N

NI

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

A

A

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

GREE

CE

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

ITALY

AL

SWITZERLAND

ZERLAND

BE

LG

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

IU

M

U

M

ELG

G

U

U

NE

TH

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

E

E

ER

E

E

E

E

E

E

LA

ND

S

AN

HE

NE

NE

NE

ES

TO

NIA

A

LATVIA

A

LITHUANIA

A

W

HIT

E

R

USS

I

A

U

KRAIN

E

BESS

AR

R

A

AB

A

A

A

A

A

IA

RA

PO

LAN

D

LUXEMB

OU

OU

OU

U

OU

OU

U

OU

U

U

RG

RG

OU

OU

OU

OU

U

OU

OU

OU

OU

OU

OU

OU

CR

R

CR

R

CR

R

CR

CR

R

CR

CR

R

R

C

C

IM

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

E

E

EA

EA

EAEA

EA

E

E

E

E

E

EA

CR

R

R

CR

CR

R

R

R

R

C

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

E

EA

EA

E

EA

EA

EA

E

E

TU

RKEY

Z

one

C

Z

E

C

H

O

S

L

O

V

A

K

I

A

B

lack

S

ea

Baltic

S

ea

M

editerranean Sea

D

a

D

D

n

u

b

e

b

b

R.

O

d

O

e

d

d

r

R

.

P

o

R

.

0

300

600

M

ile

e

s

s

0

300 600 900 Kilometer

s

F

rench

S

ector

British Sector

U

.

S

.

S

ector

S

o

vi

e

t

S

ector

EA

ST

BERLIN

E

A

S

T

G

ERMANY

E

A

S

T

G

ERMANY

P

ots

d

a

m

WE

ST

BERLIN

L

E

A

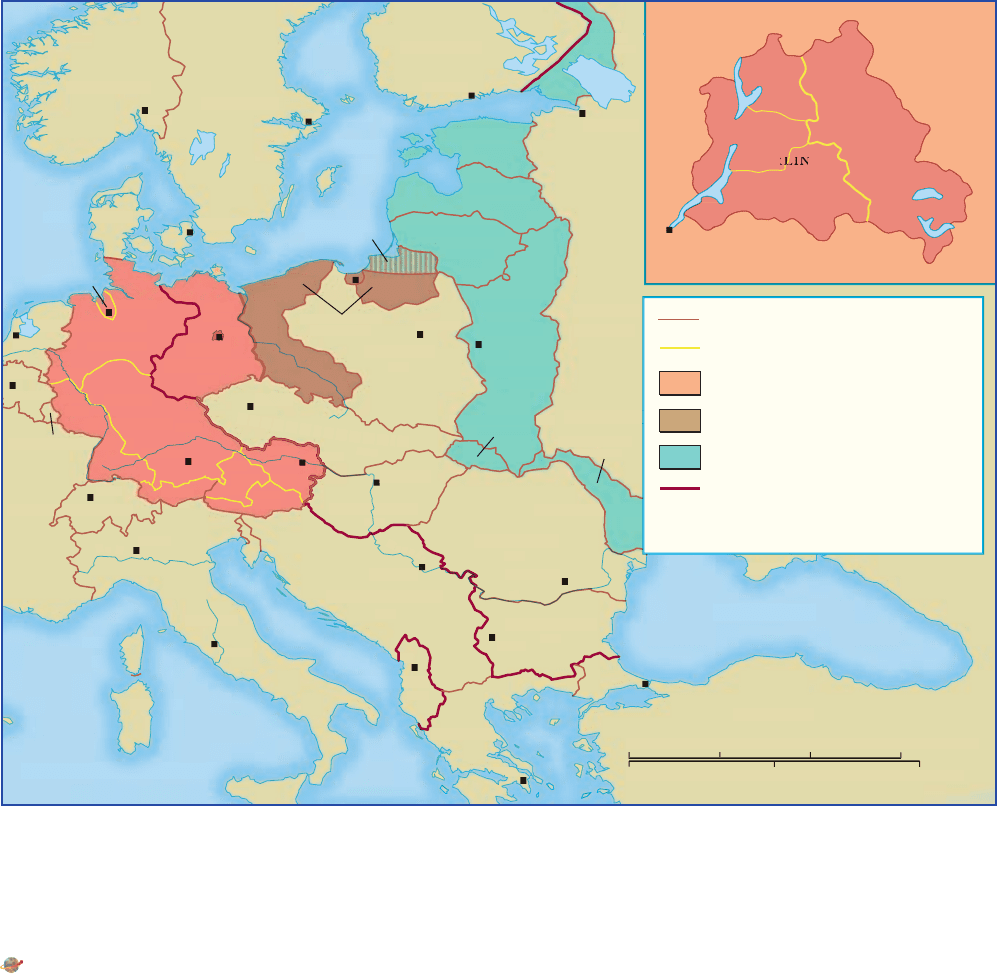

National boundaries in 1949

Allied sector boundaries

Allied occupation of Germany and

Austria, 1945–1955

Territory lost by Germany

Territory gained by Soviet Union

“Iron Curtain” after 1955

Year Communist control of

government was gained

1945

MAP 25.3 Territorial Changes in Europe After World War II. In the last months of World

War II, the Red Army occupied much of eastern Europe. Stalin sought pro-Soviet satellite

states in the region as a buffer against future invasions from western Europe, whereas Britain

and the United States wanted democratically elected governments. Soviet military control of the

territory settled the question.

Q

Which country gained the greatest territory at the expense of Germany?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www .cengage.com/history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

AFTERMATH OF THE WAR 637

By the time of the conference at Ya lta in southern

Russia in February 1945, the defeat of Germany was a

foregone conclusion. The Western powers now faced the

reality of 11 million Red Army soldier s ta king posses-

sion of large portions of Euro pe. Stalin, deeply suspi-

cious of the Western powers, desired a buffer to protect

the Soviet Union from possible future Western aggres-

sion but at the same time was eager t o obtain impor tant

resources and strategic military positions. Roosevelt

by this time was moving toward the idea of self-

determination for Europe. The Grand Alliance approved

the ‘‘Declaration on Liberated E ur ope.’’ This was a pledge

to assist liberated European nations in the creation of

‘‘democratic institutions of their own choice.’’ Liberated

countries were to hold free elections to determine their

political systems.

At Yalta, Roosevelt sought Russian military help

against Japan. Development of the atomic bomb was not

yet assured, and American military planners feared the

possible loss of as many as one million men in invading

the Japanese home islands. Roosevelt therefore agreed

to Stalin’s price for military assistance against Japan:

possession of Sakhalin and the Kurile Islands, as well as

railroad rights in Manchuria.

The creation of the United Nations was a major

American concern at Yalta. Roosevelt hoped to ensure the

participation of the Big Three in a postwar international

organization before difficult issues divided them into

hostile camps. After a number of compromises, both

Churchill and Stalin accepted Roosevelt’s plans for a

United Nations organization and set the first meeting for

San Francisco in April 1945.

The issues of Germany and eastern Europe were

treated less decisively. The Big Three reaffirme d that

Germany must surrender uncondi tionally and created

four occupation zones (see Map 25.3 on p. 637). A

compromise was a lso worked out in regard to Poland.

Stali n agreed to free elections in the future to determine

a new government. But the issue o f free elections

in eastern Europe caused a serious rift between the

Soviets and the Americans. The principle was that east-

ern European governments would be freely elected, but

they were also supposed to be pro-Russian. This attempt

to reconcile two irreconcilable goals was doomed to

failure, as soon became ev ident at the next conference of

the Big Three.

The Potsdam conference of July 1945 began under

a cloud of mistrust. Roosevelt had died on April 12 and

had been succeeded as president by Harr y Truman. At

Potsdam, Truman demanded free elections throughout

eastern Euro pe. Stalin responded, ‘‘A freely elected

government in any of these East European countries

would be anti-Soviet, and that we cannot allow.’’

10

After a bitterly foug ht and devastating war, Stalin

sought absolute military security. To him, it could be

gained only by the presence of Communist states in

eastern Europe. Free elections might result in govern-

ments hostile to the Soviets. By the middle of 1945,

only an invasion by Western force s could undo devel-

opments in eastern Europe, and few people favored

such a policy.

As the war slowly receded into the past, the reality of

conflicting ideologies reappeared (see the comparative

essay on p. 634). Many in the West interpreted Soviet

policy as part of a worldwide Communist conspiracy.

The Soviets, for their part, viewed Western---especially

American---policy as nothing less than global capitalist

expansionism or, in Leninist terms, economic imperial-

ism. In March 1946, in a speech to an American audience,

former British prime minister Winston Churchill de-

clared that ‘‘an iron curtain’’ had ‘‘descended across the

continent,’’ dividing Germany and Europe into two hos-

tile camps. Stalin branded Churchill’s speech a ‘‘call to

war with the Soviet Union.’’ Only months after the

world’s most devastating conflict had ended, the world

seemed once again to be bitterly divided.

CONCLUSION

WORLD WAR II was the most devastating total war in human

history. Germany, Italy, and Japan had been utterly defeated. Perhaps

as many as 60 million people---combatants and civilians---had been

killed in only six years. In Asia and Europe, cities had been reduced to

rubble, and millions of people faced starvation as once fertile lands

stood neglected or wasted.

What were the underlying causes of the war? One direct cause was

the effort by two rising powers, Germany and Japan, to make up for

their relatively late arrival on the scene to carve out global empires. Key

elements in both countries had resented the agreements reached after

the end of World War I, which divided the world in a manner favorable

to their rivals, and hoped to overturn them at the earliest opportunity.

In Germany and Japan, the legacy of a past marked by a strong military

tradition still wielded strong influence over the political system and the

mindset of the entire population. It is no surprise that under the

impact of the Great Depression, which had severe effects in both

countries, militant forces determined to enhance national wealth and

power soon overwhelmed fragile democratic institutions.

Whatever the causes of World War II, the consequences were

soon evident. European hegemony over the world was at an end, and

638 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

SUGGESTED READING

The Dictatorial Regimes For a general study of fascism,

see S. G. Payne, A History of Fascism (Madison, Wis., 1996), and

R. O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism (New York, 2004). The best

biography of Mussolini is R. J. B. Bosworth, Mussolini (London,

2002). On Fascist Italy, see R. J. B. Bosworth, Mussolini’s Italy: Life

Under the Fascist Dictatorship (New York, 2006).

Two brief but sound surveys of Nazi Germany are J. J.

Spielvogel, Hitler and Nazi Germany: A History, 5th ed. (Upper

Saddle River, N.J., 2005), and W. Benz, A Concise History of the

Third Reich, trans T. Dunlap (Berkeley, Calif., 2006). The best

biography of Hitler is I. Kershaw, Hitler, 1889--1936: Hubris (New

York, 1999), and Hitler: Nemesis (New York, 2000). On the rise of

the Nazis to power, see R. J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich

(New York, 2004), and The Third Reich in Power, 1933--1939 (New

York, 2005).

The collectivization of agriculture in the Soviet Union

is examined in S. Fitzpatrick, Stalin’s Peasants: Resistance and

Survival in the Russian Village After Collectivization (New York,

1995). Industrialization is covered in H. Kuromiya, Stalin’s

Industrial Revolution: Politics and Workers, 1928--1932 (New York,

1988). On Stalin himself, see R. Service, Stalin: A Biography

(Cambridge, Mass., 2006), and R. W. Thurston, Life and Terror

in Stalin’s Russia, 1934--1941 (New Haven, Conn., 1996).

The Path to War On the causes of World War II, see

A. J. Crozier, Causes of the Second World War (Oxford, 1997).

two new superpowers had emerged on the fringes of Western

civilization to take its place. Even before the last battles had been

fought, the United States and the Soviet Union had arrived at

different visions of the postwar world, and their differences soon led

to the new and potentially even more devastating conflict known as

the Cold War. And even though Europeans seemed merely pawns in

the struggle between the two superpowers, they managed to stage a

remarkable recovery of their own civilization. In Asia, defeated Japan

made a miraculous economic recovery, while the era of European

domination finally came to an end.

TIMELINE

1925

1930 1935 1940 1945

Europe

Asia

Mussolini creates Fascist

dictatorship in Italy

Stalin’s first

five-year plan begins

Japanese attack

on Pearl Harbor

Conferences

at Yalta and

Potsdam

The Holocaust

Japanese takeover of Manchuria

Kristallnacht

Atomic bomb

dropped on

Hiroshima

Hitler and Nazis come

to power in Germany

Fall of France German defeat

at Stalingrad

Japanese create Ministry

for Great East Asia

CONCLUSION 639

On the origins of the war in the Pacific, see A. Iriye, The Origins of

the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific (London, 1987).

World War II General works on World War II include the

comprehensive study by G. Weinberg, A World at Arms: A Global

History of World War II, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, 2005), and

J . Campbell, TheExperienceofWorldWarII(New York, 1989). For

briefer histories, see J. Plowright, Causes, Course, and Outcomes of

World War II (New York, 2007), and M. J. L yon, Wor ld War II: A

Short History, 4th ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J., 2004).

The Holocaust Excellent studies of the Holocaust include

R. Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, rev. ed., 3 vols.

(New York, 1985); S. Fried

€

ander, The Years of Extermination: Nazi

Germany and the Jews, 1939--1945 (New York, 2007); and L. Yahil,

The Holocaust (New York, 1990). For brief studies, see J. Fischel,

The Holocaust (Westpor t, Conn., 1998), and D. Dwork and R. J.

van Pelt, Holocaust: A History (New York, 2002).

The Home Front On the home front in Germany, see

M. Kitchen, Nazi Germany at War (New York, 1995). The Soviet

Union during the war is examined in M . Harrison, Sov iet

Planning in Peace and War, 1938--1945 (Cambridge, 1985). The

Japanese home front is examined in T. R. H. Havens, The Valley

of Darkness: The Japanese Peo ple and World War Two (New

York, 1978).

On the Allied bombing campaign against Germany, see

R. Neillands, The Bomber War: The Allied Air Offensive Against

Nazi Germany (New York, 2005), and J. Friedrich, The Fire: The

Bombing of Germany, trans. A. Brown (New York, 2006). On the use

of the atomic bomb in Japan, see M. Gordin, Five Days in August:

How World War II Became a Nuclear War (Princeton, N.J., 2006).

Emergence of the Cold War On the emergence of the Cold

War, see L. Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (New York,

2005); J. W. Langdon, A Hard and Bitter Peace: A Global History

of the Cold War (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1995); and J. Smith, The

Cold War, 1945--1991 (Oxford, 1998).

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

640 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

641

PART

V

T

OWARD A

G

LOBAL

C

IVILIZATION

?

T

HE

W

ORLD

S

INCE

1945

26 EAST AND WEST IN THE GRIP

OF THE

COLD WAR

27 BRAVE NEW WORLD:COMMUNISM

ON

TRIAL

28 EUROPE AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE

SINCE 1945

29 CHALLENGES OF NATION BUILDING

IN

AFRICA AND THE MIDDLE EAST

30 TOWARD THE PACIFIC CENTURY?

EPILOGUE: AGLO BAL CIVILIZATION

AS WORLD WAR II came to an end, the survivors of that bloody

struggle could afford to face the future with a cautious optimism.

Europeans might hope that the bitter rivalry that had marked relations

among the Western powers would finally be put to an end and that the

wartime alliance of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet

Union could be maintained into the postwar era.

More than sixty years later, these hopes have been only partly

realized. In the decades following the war, the Western capitalist

nations managed to recover from the economic depressio n that had led

into World War II and advanced to a level of economic prosperity never

seen be fore. The bloody con flicts that had erupted among European

nations during the first half of the twentiet h century ca me to an end,

and Ge rmany and Japan were fully integrated into the world

community.

At the same time, the prospects for a stable, peaceful world and an

end to balance-of-power politics were hampered by the emergence of a

grueling and sometimes tense ideological struggle between the socialist

and capitalist camps, a competition headed by the only remaining great

powers, the Soviet Union and the United States.

In the shadow of this rivalry, the Western European states made a

remarkable economic reco v ery and reached untold levels of prosperity. In

Eastern Europe, Soviet domination, both politically and economically,

seemed so complete that many doubted it could ever be undone. But

communism had never developed deep roots in Eastern Europe, and in

the late 1980s, when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev indicated that his

government would no longer pursue military intervention, Eastern

European states acted quickly to establish their freedom and adopt new

economic structures based on Western models.

Outside the West, the peoples of Africa and Asia had their own

reasons for optimism as World War II came to a close. In the Atlantic

Charter, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill had set forth a joint

declaration of their peace aims calling for the self-determination of all

peoples and self-government and sovereign rights for all nations that had

been deprived of them.

As it turned out, some colonial powers were reluctant to divest

themselves of their colonies. Still, World War II had severely undermined

the stability of the colonial order, and by the end of the 1940s, most

colonies in Asia had received their independence. Africa followed a decade

or two later.

Broadly speaking, the leaders of these newly liberated countries set

forth three goals at the outset of independence. They wanted to throw off

the shackles of Western economic domination and ensure material

prosperity for all of their citizens. They wanted to introduce new po-

litical institutions that would enhance the right of self-determination of

their peoples. And they wanted to develop a sense of common nation-

hood within the population and establish secure territorial boundaries.

Most opted to follow a capitalist or a moderately socialist path toward

economic development. In a few cases---most notably in China and

Vietnam---revolutionary leaders opted for the Communist mode of

development.

Regardless of the path chosen, the results were often disappointing.

Much of Africa and Asia remained economically dependent on the

642

advanced industrial nations. Some societies faced severe problems of

urban and rural poverty.

What had happened to tarnish the bright dream of economic

affluence? During the late 1950s and early 1960s, one school of thought

was dominant among scholars and government officials in the United

States. Known as modernization theory, this school took the view that the

problems faced by the newly independent countries were a consequence of

the difficult transition from a traditional to a modern society. Moderni-

zation theorists were convinced that agrarian countries were destined to

follow the path of the West toward the creation of modern industrial

societies but would need time as well as substantial amounts of economic

and technological assistance from the West to complete the journey.

Ev entually, modernization theory began to come under attack from a

new generation of younger scholars. In their view, the responsibility for

continued economic underdevelopment in the developing world lay not

with the countries themselves but with their continued domination by the

ex-colonial powers. In this view, known as dependency theory, the coun-

tries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America were the victims of the international

marketplac e, which charged high pric es for the manufactured goods of the

West while dooming preindustrial countries to low prices for their own raw

material exports. Efforts by such countries to build up their own industrial

sectors and mov e into the stage of self-sustaining growth were hampered by

foreign control---through European- and American-owned corporations---

over many of their resources. To end this ‘‘neocolonial’’ relationship, the

dependency theory advocates argued, developing societies should reduce

their economic ties with the West and practice a policy of economic self-

reliance, thereby taking control over their own destinies.

Leaders of African and Asian countries also encountered problems

creating new political cultures responsive to the needs of their citizens.

At first, most accepted the concept of democracy as the defining theme

of that culture. Within a decade, however, democratic systems through-

out the developing world were replaced by military dictatorships or one-

party governments that redefined the concept of democracy to fit their

own preferences. It was clear that the difficulties in building democratic

political institutions in developing societies had been underestimated.

The problem of establishing a common national identity has in

some ways been the most daunting of all the challenges facing the new

nations of Asia and Africa. Many of these new states were a composite of a

wide variety of ethnic, religious, and linguistic groups who found it dif-

ficult to agree on common symbols of nationalism. Problems of estab-

lishing an official language and delineating territorial boundaries left over

from the colonial era created difficulties in many countries. Internal

conflicts spawned by deep-rooted historical and ethnic hatreds have

proliferated throughout the world, leading to a vast new movement of

people across state boundaries equal to any that has occurred since the

great population migrations of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The introduction of Western cultural values and customs has also had

a destabilizing effect in many areas. Although such ideas are welcomed by

some groups, they are firmly resisted by others. Where Western influence

has the effect of undermining traditional customs and religious beliefs, it

often provokes violent hostility and sparks tension and even conflict within

individual societies. Mu ch of the anger recently directed at the United States

in M uslim countries has undoubtedly been generated by such feelings.

Nonetheless, social and political attitudes are changing rapidly in

many Asian and African countries as new economic circumstances have

led to a more secular worldview, a decline in traditional hierarchical

relations, and a more open attitude toward sexual practices. In part, these

changes have been a consequence of the influence of Western music,

movies, and television. But they are also a product of the growth of an

affluent middle class in many societies of Asia and Africa.

Today we live not only in a world economy but in a world society,

where a revolution in the Middle East can cause a rise in the price of oil in

the United States and a change in social behavior in Malaysia and Indo-

nesia, where the collapse of an empire in Asia can send shock wav es as far

as Hanoi and Havana, and where a terrorist attack in New York City or

London can disrupt financial markets around the world.

c William J. Duiker

TOWAR D A GLO B AL CIVILIZATION?THE WORLD SINCE 1945 643

CHAPTER 26

EAST AND WEST IN THE GRIP OF THE COLD WAR

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

The Collapse of the Grand Alliance

Q

Why were the United States and the Soviet Union

suspicious of each other after World War II, and what

events between 1945 and 1949 heightened the tensions

between the two nations?

Cold War in Asia

Q

How and why did Mao Zedong and the Communists

come to power in China, and what were the Cold War

implications of their triumph?

From Confrontation to Coexistence

Q

What events led to the era of coexistence in the 1960s,

and to what degree did each side contribute to the

reduction in international tensions?

An Era of Equivalence

Q

Why did the Cold War briefly flare up again in the

1980s, and why did it come to a definitive end at the end

of the decade?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

How have historians answered the question of whether

the United States or the Soviet Union bears the

primary responsibility for the Cold War, and what

evidence can be presented on each side of the issue?

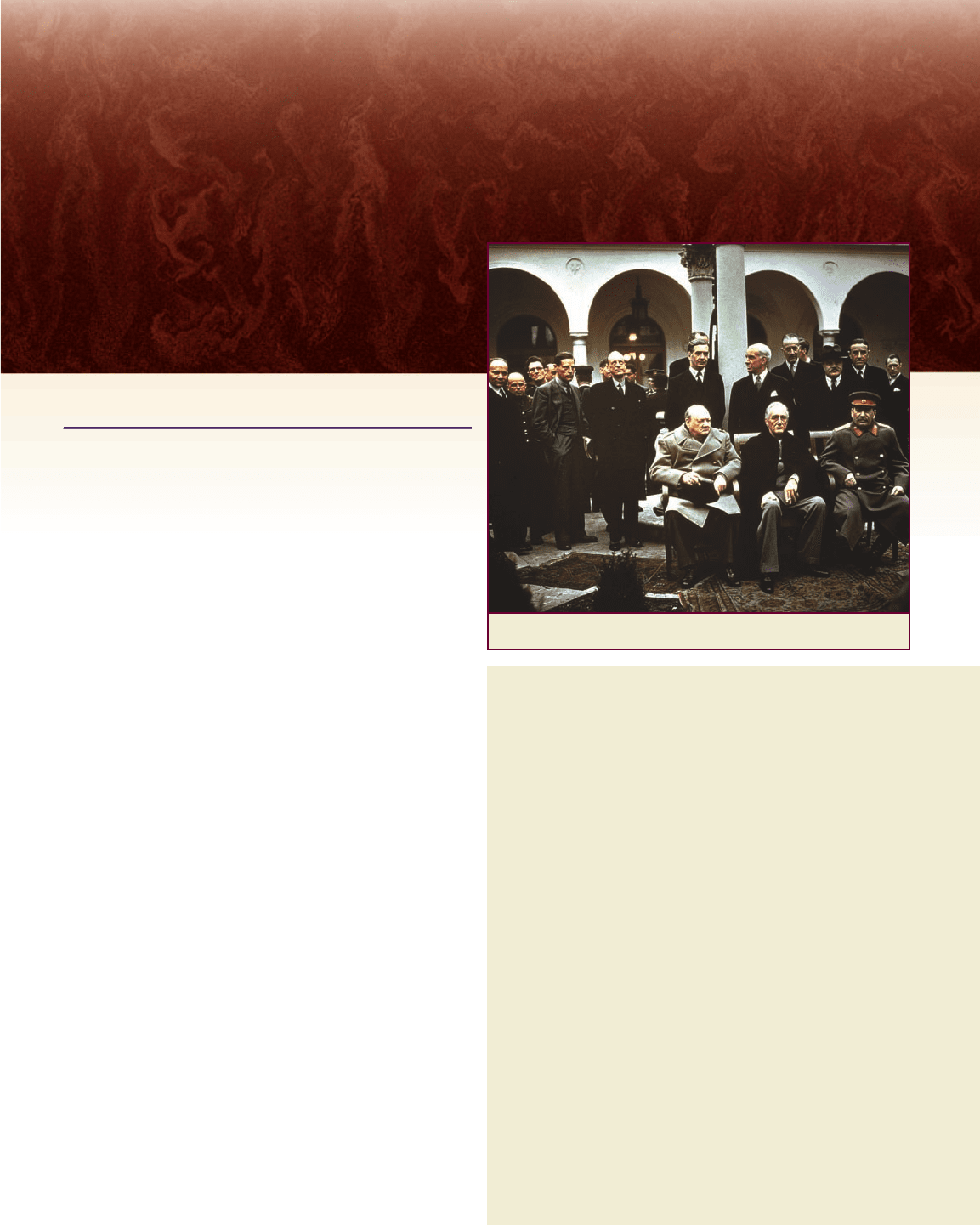

Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin at Yalta

c

The Art Archive/Imperial War Museum, London, UK

644

‘‘OUR MEETING HERE in the Crimea has reaffirmed our com-

mon determination to maintain and strengthen in the peace to

come that unity of purpose and of action which has made victory

possible and certain for the United Nations in this war. We believe

that this is a sacred obligation which our Governments owe to our

peoples and to all the peoples of the world.’’

1

With these ringing words, drafted at the Yalta Conference in

February 1945, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Soviet leader

Joseph Stalin, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

affirmed their common hope that the Grand Alliance that had been

victorious in World War II could be sustained into the postwar era.

Only through continuing and growing cooperation and understand-

ing among the three Allies, the statement asserted, could a secure

and lasting peace be realized that, in the words of the Atlantic Char-

ter, would ‘‘afford assurance that all the men in all the lands may

live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.’’

Roosevelt hoped that the decisions reached at Yalta would pro-

vide the basis for a stable peace in the postwar era. Allied occupa-

tion forces---American, British, and French in the west and Soviet in

the east---were to bring about the end of Axis administration and to

organize the free election of democratic governments throughout

The Collapse of the Grand Alliance

Q

Focus Question: Why were the United States and the

Soviet Union suspicious of each other after World

War II, and what events between 1945 and 1949

heightened the tensions between the two nations?

The problems started in Europe. At the end of the war,

Soviet military forces occupied all of Eastern Europe and

the Balkans (except Greece, Albania, and Yugoslavia),

while U.S. and other Allied forces secured the western part

of the Continent. Roosevelt had assumed that free elec-

tions, administered promptly by ‘‘democratic and peace-

loving forces,’’ would lead to democratic governments

responsive to the local population. But it soon became

clear that the Soviet Union interpreted the Yalta agreement

differently. When Soviet occupation authorities began

forming a new Polish government, Stalin refused to accept

the Polish government-in-exile---headquartered in London

during the war and composed primarily of landed aris-

tocrats who harbored a deep distrust of the Soviet

Union---and instead set up a government composed of

Communists who had spent the war in Moscow. Roosevelt

complained to Stalin but eventually agreed to a compro-

mise whereby two members of the London government

were included in the new Communist regime. A week

later, Roosevelt was dead of a cerebral hemorrhage,

emboldening Stalin to do pretty much as he pleased.

Soviet Domination of Eastern Europe

Similar developments took place in all of the states oc-

cupied by Soviet troops. Coalitions of all political parties

(except fascist or right-wing parties) were formed to run

the government, but within a year or two, the Communist

Party in each coalition had assumed the lion’s share of

power. It was then a short step to the establishment of

one-party Communist governments. Between 1945 and

1947, Communist governments became firmly en-

trenched in East Germany, Bulgaria, Romania, Poland,

and Hungary. In Czechoslovakia, with its strong tradition

of democratic institutions, the Communists did not

achieve their goals until 1948. After the Czech elections of

1946, the Communist Party shared control of the gov-

ernment with the non-Communist parties. When it ap-

peared that the latter might win new elections early in

1948, the Communists seized control of the government

on February 25. All other parties were dissolved, and the

Communist leader Klement Gottwald became the new

president of Czechoslovakia.

Yugoslavia was a notable exception to the pattern of

Soviet dominance in Eastern Europe. The Communist

Party there had led resistance to the Nazis during the war

and easily assumed power when the war ended. Josip Broz,

known as Tito (1892--1980), the leader of the Communist

resistance movement, appeared to be a loyal Stalinist. After

the war, however, he moved to establish an independent

Communist state. Stalin hoped to take contr ol of Yugo-

slavia, but Tito refused to capitulate to Stalin’s demands

and gained the support of the people (and some sympathy

in the West) by portraying the struggle as one of Yugoslav

national freedom. In 1958, the Yugoslav party congress

asserted that Yugoslav Communists did not see themselves

as deviating from communism, only from Stalinism.

They considered their more decentralized system, in which

workers managed themselves and local communes

exercised some political power, closer to the Marxist-

Leninist ideal.

To Stalin (who had once boasted, ‘‘I w ill shake my

little finger, and there will be no more Tito’’), the cre-

ation of pliant pro-Soviet regimes throughout Eastern

Europe may simply have repres ented his interpretation

of the Yalta peace agreement and a reward for sacrifices

suffered durin g the war, satisfyin g Moscow’s aspirations

for a buffer zone against the capitalist West. If the Soviet

leader had any i ntention of promoting future Com-

munist revolutions in Western Europe---and there is

some indication that he did---such developments would

have to await the appearance of a new capitalist crisis a

decade or more into the future. As Stalin undoubtedly

recalled, Lenin had always maintained that revolutions

come in waves.

Descent of the Iron Curtain

To the United States, however, the Soviet takeover of

Eastern Europe represented an ominous development

that threatened Roosevelt’s vision of a durable peace.

Public suspicion of Soviet intentions grew rapidly,

THE COLLAPSE OF THE GRAND ALLIANCE 645

Europe. To foster mutual trust and an end to the suspicions that

had marked relations between the capitalist world and the Soviet

Union prior to the war, Roosevelt tried to reassure Stalin that Mos-

cow’s legitimate territorial aspirations and genuine security needs

would be adequately met in a durable peace settlement.

It was not to be. Within months after the German surrender,

the mutual trust among the Allies---if it had ever truly existed---rap-

idly disintegrated, and the dream of a stable peace was replaced by

the specter of a potential nuclear holocaust. The United Nations,

envisioned by its founders as a mechanism for adjudicating interna-

tional disputes, became mired in partisan bickering. As the Cold

War between Moscow and Washington intensified, Europe was di-

vided into two armed camps, while the two superpowers, glaring at

each other across a deep ideological divide, held the survival of the

entire world in their hands.