Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The need for industrial labor also led Latin American

countries to encourage immigration from Europe. Between

1880 and 1914, three million Europeans, primarily Italians

and Spaniards, settled in Argentina. More than 100,000

Europeans, mostly Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish, ar-

rived in Brazil each year between 1891 and 1900.

As in Europe and the United States, industrialization

led to urbanization, evident in both the emergence of new

cities and the rapid growth of old ones. By 1900 Buenos

Aires (the ‘‘Paris’’ of South America) had 750,000 in-

habitants, and by 1914 it had two million---a fourth of

Argentina’s population.

Political Change in Latin America

Latin America also experienced a political transformation

after 1870. Large landowners began to take a more direct

interest in national politics and even in governing. In

Argentina and Chile, for example, landholding elites

controlled the governments, and although they produced

constitutions similar to those of the United States and

European nations, they ensured their power by regulating

voting rights.

In some countries, large landowners supported dic-

tators to ensure the interests of the ruling elite. Porfirio

Dı

´

az, who ruled Mexico from 1876 to 1910, created a

conservative, centralized government with the support of

the army, foreign capitalists, large landowners, and the

Catholic church. Nevertheless, there were forces for

change in Mexico that led to revolution in 1910.

During Dı

´

az’s dictatorial reign, 95 percent of the

rural population owned no land at all, while about one

thousand families owned almost all of Mexico. When a

liberal landowner, Francisco Madero, forced Dı

´

az from

power, he opened the door to a wider revolution. Ma-

dero’s ineffectiveness created a demand for agrarian re-

form led by Emiliano Zapata, who aroused the masses of

landless peasants and began to seize the estates of the

wealthy landholders. Between 1910 and 1920, the revo-

lution caused untold destruction to the Mexican econ-

omy. Finally, in 1917 a new constitution established a

strong presidency, implemented land reform policies,

placed limits on foreign investors, and set an agenda for

social welfare for workers.

By this time, a new power had begun to wi eld its

influence over Latin America. By 1900, t he United

States, which had begun to emerge as a great world

power, began to interfere in the affairs of its southern

nei ghbors. As a result of the Spanish-America n War

(1898), Cuba became a U.S. protectorate, and Puerto

Rico was annexed outright to the United States.

American investment s in Latin America soon followed;

so did American resolve to protect these investments.

Between 1898 and 1934, American military forces were

sent to Cuba, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicara-

gua, Panama, Colombia, Haiti, and the Dominican

Republic to protect American interests. At the same

time, the United States became the chief foreign investor

in Latin America.

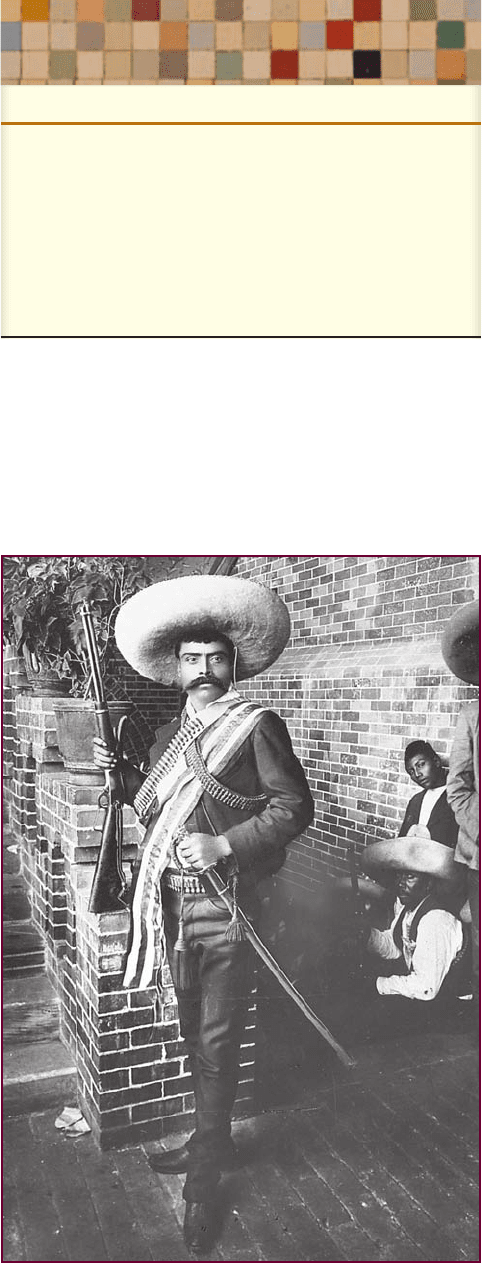

Emiliano Zapata. The inability of Francisco Madero to carry out far-

reaching reforms led to a more radical upheaval in the Mexican countryside.

Emiliano Zapata led a band of Indians in a revolt against the large

landowners of southern Mexico and issued his own demands for land reform.

CHRONOLOGY

Latin America

Revolt in Mexico 1810

Bolı

´

varandSanMartı

´

n free most of South America 1810--1824

Augustı

´

n de Iturbide becomes emperor of Mexico 1821

Brazil gains independence from Portugal 1822

Monroe Doctrine 1823

Rule of Porfirio Dı

´

az in Mexico 1876--1910

Mexican Revolution begins 1910

c

Snark/Art Resource, NY

496 CHAPTER 20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

The North American Neighbors:

The United States and Canada

Q

Focus Questions: What role did nationalism and

liberalism play in the United States and Canada

between 1800 and 1870? What economic, social, and

political trends were evident in the United States and

Canada between 1870 and 1914?

Colonial Latin America had distinctive features that dif-

fered from those found in the North American colonies.

The North American colonies were a part of the British

Empire, and although they gained their freedom from the

British at different times, both the United States and

Canada emerged as independent and prosperous nations

whose political systems owed much to British political

thought. In the nineteenth century, both the United States

and Canada faced difficult obstacles in achieving national

unity.

The Growth of the United States

The U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1789, committed the

United States to two of the major influences of the first

half of the nineteenth century, liberalism and nationalism.

A strong force for national unity came from the Supreme

Court while John Marshall (1755--1835) was chief justice

from 1801 to 1835. Marshall made the Supreme Court

into an important national institution by asserting the

right of the Court to overrule an act of Congress if the

Court found it to be in violation of the Constitution.

Under Marshall, the Supreme Court contributed further

to establishing the supremacy of the national government

by curbing the actions of state courts and legislatures.

The election of Andrew Jackson (1767--1845) as

president in 1828 opened a new era in American politics,

the era of mass democracy. The electorate was expanded

by dropping property qualifications; by the 1830s, suf-

frage had been extended to almost all adult white males.

During the period from 1815 to 1850, the traditional

liberal belief in the improvement of human beings was

also given concrete expression through the establishment

of detention schools for juvenile delinquents and new

penal institutions, both motivated by the liberal belief

that the right kind of environment would rehabilitate

wayward individuals.

Slavery and the Coming of War By the mid-nineteenth

century , American national unity was increasingly threat-

ened by the issue of slavery. Both North and South had

grown dramatically during the first half of the nineteenth

century, but in different ways. The cotton economy and

social structure of the South were based on the exploita-

tion of enslaved black Africans and their descendants.

Although the importation of new slaves had been barred

in 1808, there were four million slaves in the South by

1860---four times the number sixty years earlier. The cot-

ton economy depended on plantation-based slavery, and

the South was determined to maintain them. In the

North, many people feared the spread of slavery into

western territories.

As polarization over the issue of slavery intensified,

compromise became less feasible. When Abraham Lin-

coln, the man who had said in a speech in Illinois in 1858

that ‘‘this government cannot endure permanently half

slave and half free,’’ was elected president in November

1860, the die was cast. Lincoln, the Republicans’ second

presidential candidate, carried only 2 of the 1,109 coun-

ties in the South; the Republican Party was not even on

the ballot in ten southern states. On December 20, 1860, a

South Carolina convention voted to repeal the state’s

ratification of the U.S. Constitution. In February 1861, six

more southern states did the same, and a rival nation, the

Confederate States of America, was formed. In April,

fighting erupted between North and South.

The Civil War The American Civil War (1861--1865)

was an extraordinarily bloody struggle, a foretaste of the

total war to come in the twentieth century. More than

600,000 soldiers died, either in battle or from deadly in-

fectious diseases spawned by filthy camp conditions.

Over a period of four years, the Union states of the

North mobilized their superior assets and gradually wore

down the Confederate forces of the South. As the war

dragged on, it had the effect of radicalizing public

opinion in the North. What began as a war to save the

Union became a war against slavery. On January 1, 1863,

Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, declaring

most of the nation’s slaves ‘‘forever free’’ (see the box on

p. 483 in Chapter 19). An increasingly effective Union

blockade of the ports of the South, combined with a

shortage of fighting men, made the Confederate cause

desperate by the end of 1864. The final push of Union

troops under General Ulysses S. Grant forced General

Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army to surrender on April

9, 1865. Although problems lay ahead, the Union victory

reunited the country and confirmed that the United

States would thereafter again be ‘‘one nation, indivisible.’’

The Rise of the United States

Four years of bloody civil war had restored American

national unity. The old South had been destroyed; one-

fifth of its adult white male population had been killed,

and four million black slaves had been freed. For a while

THE NORTH AMERICAN NEIGHBOR S:THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA 497

at least, a program of radical change in the South was

attempted. Slavery was formally abolished by the Thir-

teenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1865, and the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments extended citi-

zenship to blacks and gave black men the right to vote.

Radical Reconstruction in the early 1870s tried to create a

new South based on the principle of the equality of black

and white people, but the changes were soon mostly

undone. Militia organizations, such as the Ku Klux Klan,

used violence to discourage blacks from voting. A new

system of sharecropping made blacks once again eco-

nomically dependent on white landowners. New state

laws made it nearly impossible for blacks to exercise their

right to vote. By the end of the 1870s, supporters of white

supremacy were back in power everywhere in the South.

Prosperity and Progressivism Between 1860 and 1914,

the United States made the shift from an agrarian to a

mighty industrial nation. American heavy industry stood

unchallenged in 1900. In that year, the Carnegie Steel

Company alone produced more steel than Great Britain’s

entire steel industry. Industrialization also led to urban-

ization. Whereas 20 percent of Americans lived in cities in

1860, more than 40 percent did in 1900.

The United States had become the world’s richest

nation and greatest industrial power. Yet serious ques-

tions remained about the quality of American life.

In 1890, the richest 9 percent of

Americans owned an incredible

71 percent of all the wealth. La-

bor unrest over unsafe working

conditions, strict work discipline,

and periodic cycles of devastating

unemployment led workers to

organize. By the turn of the

century, one national organiza-

tion, the American Federation of

Labor, emerged as labor’s domi-

nant voice. Its lack of real power,

however, was reflected in its

membership figures. In 1900, it

included only 8.4 percent of the

American industrial labor force.

During the so-called Pro-

gressive Era after 1900, reform

swept the United States. State

governments enacted laws that

governed hours, wages, and

working conditions, especially

for women and children. The

realization that stat e laws were

ineffective in dealing w ith na-

tionwide problems, however, led

to a Progressive movement at the national level. The

Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act

provided for a limited degree of federal regulation of

industrial practices. The presidency of Woodrow Wilson

(1913--1921) witnessed the enactment of a graduated

federal income tax and the establishment of the Federal

Reserve System, whic h perm itt ed the national govern-

ment to play a role in important economic decisions

formerly made by bankers. Like European nations, the

United States was slowly adopting policies that broad-

ened the functions of the state.

The United States as a World Power At the end of the

nineteenth century, the United States began to expand

abroad. The Samoan Islands in the Pacific became the

first important American colony; the Hawaiian Islands

were next. By 1887, American settlers had gained control

of the sugar industry on the Hawaiian Islands. As more

Americans settled in Hawaii, they sought political power.

When Queen Liliuokalani tried to strengthen the mon-

archy in order to keep the islands for the native peoples,

the U.S. government sent Marines to ‘‘protect’’ American

lives. The queen was deposed, and Hawaii was annexed by

the United States in 1898.

The defeat of Spain in the Spanish-American War in

1898 expanded the American empire to include Cuba,

Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. Although the

The D ead at Antie tam. National unity in the United States dissolved over the issue of slavery and led

to a bloody civil war that cost 600,000 American lives. This photograph shows the southern dead after the

Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. The invention of photography in the 1830s made it possible to

document the horrors of war in the most graphic manner.

c

Peter Newark Military Pictures/The Bridgeman Art Library

498 CHAPTER 20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

Filipinos appealed for independence, the Americans re-

fused to grant it. As President William McKinley said, the

United States had the duty ‘‘to educate the Filipinos and

uplift and Christianize them,’’ a remarkable statement in

view of the fact that most of them had been Roman

Catholics for centuries. It took three years and 60,000

troops to pacify the Philippines and establish U.S. control.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the United

States had an empire.

The Making of Canada

North of the United States, the process of nation building

was also making progress. Under the Treaty of Paris in

1763, Canada---or New France, as it was called---passed

into the hands of the British. By 1800, most Canadians

favored more autonomy, although the colonists disagreed

on the form this autonomy should take. Upper Canada

(now Ontario) was predominantly English speaking,

whereas Lower Canada (now Quebec) was dominated by

French Canadians.

In 1837, a number of Canadian groups rose in re-

bellion against British authority. Although the rebellions

were crushed by the following year, the British govern-

ment now began to seek ways to satisfy some of the Ca-

nadian demands. The U.S. Civil War proved to be a

turning point. Fearful of American designs on Canada

during the war, the British government finally capitulated

to Canadian demands. In 1867, Parliament established the

Dominion of Canada, with its own constitution. Canada

now possessed a parliamentary system and ruled itself,

although foreign affairs still remained under the control of

the British government.

Canada faced problems of national unity between

1870 and 1914. At the beginning of 1870, the Dominion of

Canada had only four provinces: Quebec, Ontario, Nova

Scotia, and New Brunswick. With the addition of two

more provinces in 1871---Manitoba and British Columbia---

the Dominion now extended from the Atlantic Ocean to

the Pacific. As the first prime minister, John Macdonald

(1815--1891) moved to strengthen Canadian unity. He

pushed for the construction of a transcontinental railroad,

which was completed in 1885 and

opened the western lands to indus-

trial and commercial development.

This also led to the incorporation of

two more provinces---Alberta and

Saskatchewan---in 1905 into the

Dominion of Canada.

R eal unity was difficult to

achieve, howev er, because of the dis-

trust between the English-speaking

majority and the Fr ench-speaking

Canadians, living primarily in Quebec. Wilfr ed Laurier,

who became the first French Canadian prime minister in

1896, was able to reconcile Canada’s two major groups and

resolv e the issue of separate schools for French Canadians.

During Laurier’ s administration, industrialization boomed,

especially the production of textiles, furniture, and rail wa y

equipment. Hundreds of thousands of immigrants, pri-

marily from central and eastern Europe, also flowed into

Canada. Many settled on lands in the west, thus helping

populate Canada’s vast territories.

The Emergence of Mass Society

Q

Focus Question: What is meant by the term mass

society, and what were its main characteristics?

While new states were developing in the Western Hemi-

sphere in the nineteenth century, a new kind of society---a

mass society---was emerging in Europe, especially in the

second half of the nineteenth century as a result of rapid

economic and social changes. For

the lower classes, mass society

brought voting rights, an improved

standard of living, and access to

education. At the same time, how-

ever, mass society also made possible

the development of organizations

that manipulated the populations

of the nation-states. To understand

this mass society, we need to exam-

ine some aspects of its structure.

CHRONOL OGY

The United States and Canada

United States

Election of Andrew Jackson 1828

Election of Abraham Lincoln and secession

of South Carolina

1860

Civil War 1861--1865

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation 1863

Surrender of Robert E. Lee’s

Confederate Army

April 9, 1865

Spanish-American War 1898

Presidency of Woodrow Wilson 1913--1921

Canada

Rebellions 1837--1838

Formation of the Dominion of Canada 1867

Transcontinental railroad 1885

Wilfred Laurier as prime minister 1896

Hudson

Bay

UNITED STATES

Northwest

Territories

British

Columbia

Quebec

Ontario

Nova

Scotia

New

Brunswick

Manitoba

Alberta

Saskatchewan

0

500 1,000 Miles

0 750 1,500 Kilometers

Canada, 1914

THE EMERGENCE OF MASS SOCIETY 499

The New Urban Environment

One of the most important consequences of industriali-

zation and the population explosion of the nineteenth

century was urbanization. In the course of the nineteenth

century, more and more people came to live in cities. In

1800, city dwellers constituted 40 percent of the popu-

lation in Britain, 25 percent in France and Germany, and

only 10 percent in eastern Europe. By 1914, urban resi-

dents had increased to 80 percent of the population in

Britain, 45 percent in France, 60 percent in Germany, and

30 percent in eastern Europe. The size of cities also ex-

panded dramatically, especially in industrialized coun-

tries. Between 1800 and 1900, London’s population grew

from 960,000 to 6.5 million and Berlin’s from 172,000 to

2.7 million.

Urban populations grew faster than the general

population primarily because of the vast migration from

rural areas to cities. But cities also grew faster in the

second half of the nineteenth century because health and

the conditions of life in them were improving as urban

reformers and city officials used new technology to

ameliorate the urban landscape. Following the reformers’

advice, city governments set up boards of health to im-

prove the quality of housing and instituted regulations

requiring all new buildings to have running water and

internal drainage systems.

Middle-class reformers also focused on the housing

needs of the working class. Overcro wded, disease-ridden

slums were seen as dangerous not only to physical health

but also to the political and moral health of the entire

nation. V. A. Huber, a German housing reformer , wrote in

1861: ‘‘Certainly it would not be too much to say that the

home is the communal embodiment of family life. Thus,

the purity of the dwelling is almost as important for the

family as is the cleanliness of the body for the individual.’’

5

To Huber, good housing was a prerequisite for stable family

life, and without stable family life, society would fall apart.

Early efforts to attack the housing problem empha-

sized the middle-class, liberal belief in the power of pri-

vate enterprise. By the 1880s, as the number and size of

cities continued to mushroom, governments concluded

that private enterprise could not solve the housing crisis.

In 1890, a British law empowered local town councils to

construct cheap housing for the working classes. More

and more, governments were stepping into areas of ac-

tivity that they would not have touched earlier.

The Social Structure of Mass Society

At the top of European society stood a wealthy elite,

constituting but 5 percent of the population while con-

trolling between 30 and 40 percent of its wealth. In the

course of the nineteenth century, landed aristocrats had

joined with the most successful industrialists, bankers,

and merchants (the wealthy upper middle class) to form a

new elite. In many cases, marriage united the two groups.

Members of this elite, whether aristocratic or middle class

in background, assumed leadership roles in government

bureaucracies and military hierarchies.

The middle classes consisted of a variety of groups.

Below the upper middle class was a group that included

lawyers, doctors, and members of the civil service, as well

as business managers, engineers, architects, accountants,

and chemists benefiting from industrial expansion. Be-

neath this solid and comfortable middle group was a

lower middle class of small shopkeepers, traders, manu-

facturers, and prosperous peasants.

Standing between the lower middle class and the

lower classes were new groups of white-collar workers

who were the product of the Second Industrial Revolu-

tion. They were the salespeople, bookkeepers, bank tellers,

telephone operators, and secretaries. Though often paid

little more than skilled laborers, these white-collar

workers were committed to middle-class ideals of hard

work, Christian morality, and propriety.

Below the middle classes on the social scale were the

working classes, who constituted almost 80 percent of the

European population. Many of them were landholding

peasants, agricultural laborers, and sharecroppers, espe-

cially in eastern Europe. The urban working class in-

cluded skilled artisans in traditional trades, such as

cabinetmaking, printing, and jewelry making, and semi-

skilled laborers, such as carpenters, bricklayers, and many

factory workers. At the bottom of the urban working class

stood the largest group of workers, the unskilled laborers.

They included day laborers, who worked irregularly for

very low wages, and large numbers of domestic servants,

most of whom were women.

The Experiences of Women

In 1800, women were largely defined by family and

household roles. They remained legally inferior and

economically dependent. Women struggled to change

their status throughout the nineteenth century.

Marriage and the Family Many women in the nine-

teenth century aspired to the ideal of femininity popu-

larized by writers and poets. Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem

The Princess expressed it well:

Man for the field and woman for the hearth:

Man for the sword and for the needle she:

Man with the head and woman with the heart:

Man to command and woman to obey;

All else confusion.

500 CHAPTER 20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

This traditional characterization of the sexes, based on

gender-defined social roles, was virtually elevated to the

status of universal male and female attributes in the

nineteenth century. As the chief family wage earners, men

worked outside the home for pay, while women were left

with the care of the family, for which they were paid

nothing. For most women throughout most of the nine-

teenth century, marriage was viewed as the only honorable

and available career.

The most significant development in the modern

family was the decline in the number of offspring born to

the average woman. While some historians attribute in-

creased birth control to more widespread use of coitus

interruptus, or male withdrawal before ejaculation, others

have emphasized female control of family size through

abortion and even infanticide or abandonment. That a

change in attitude occurred was apparent in the devel-

opment of a movement to increase awareness of birth

control methods. Europe’s first birth control clinic

opened in Amsterdam in 1882.

The family was the central institution of middle-class

life. Men provided the family income while women fo-

cused on household and child care. The use of domestic

servants in many middle-class homes, made possible by

an abundant supply of cheap labor, reduced the amount

of time middle-class women had to spend on household

chores. At the same time, by reducing the number of

children in the family, mothers could devote more time to

child care and domestic leisure.

The middle-class family fostered an ideal of togeth-

erness. The Victorians devised the family Christmas with

its Yule log, Christmas tree, songs, and exchange of gifts.

In the United States, Fourth of July celebrations changed

from drunken revels to family picnics by the 1850s.

Women in working-class families were more accus-

tomed to hard work. Daughters in working-class families

were expected to work until they married; even after

marriage, they often did piecework at home to help

support the family. For the children of the working classes,

childhood was over by the age of nine or ten, when they

became apprentices or were employed at odd jobs.

Between 1890 and 1914, however, family patterns

among the working class began to change. High-paying

jobs in heavy industry and improvements in the standard

of living made it possible for working-class families to

depend on the income of husbands and the wages of

grown children. By the early twentieth century, some

working-class mothers could afford to stay at home,

follow ing the pattern of middle-class women.

The Movement for Women’s Rights Modern Euro-

pean feminism, or the movement for women’s rights, had

its beginnings during the French Revolution, when some

women advocated equality for women based on the

doctrine of natural rights. In the 1830s, a number of

women in the United States and Europe, who worked

together in several reform movements, argued for the

right of women to divorce and own property.

These early efforts were not overly successful;

women did not gain the right to their own

property until 1870 in Britain, 1900 in Germany,

and 1907 in France.

The fight for property rights was only a

beginning for the women ’s movement, however.

Some middle- and upper-middle-class women

gained access to higher education, and others

sought entry into occupations dominated by

men. The first to fall was teaching. As medical

training was largely closed to women, they

sought alternatives in the development of nurs-

ing. Nursing pioneers included the British nurse

Florence Nightingale, whose efforts during the

Crimean War (1854--1856), along with those of

Clara Barton in the American Civil War (1861--

1865), transformed nursing into a profession of

trained, middle-class ‘‘women in white.’’

By the 1840s and 1850s, the movement for

women’s rights had entered the political arena

with the call for equal political rights. Many

feminists believed that the right to vote was the

key to all other reforms to improve the position

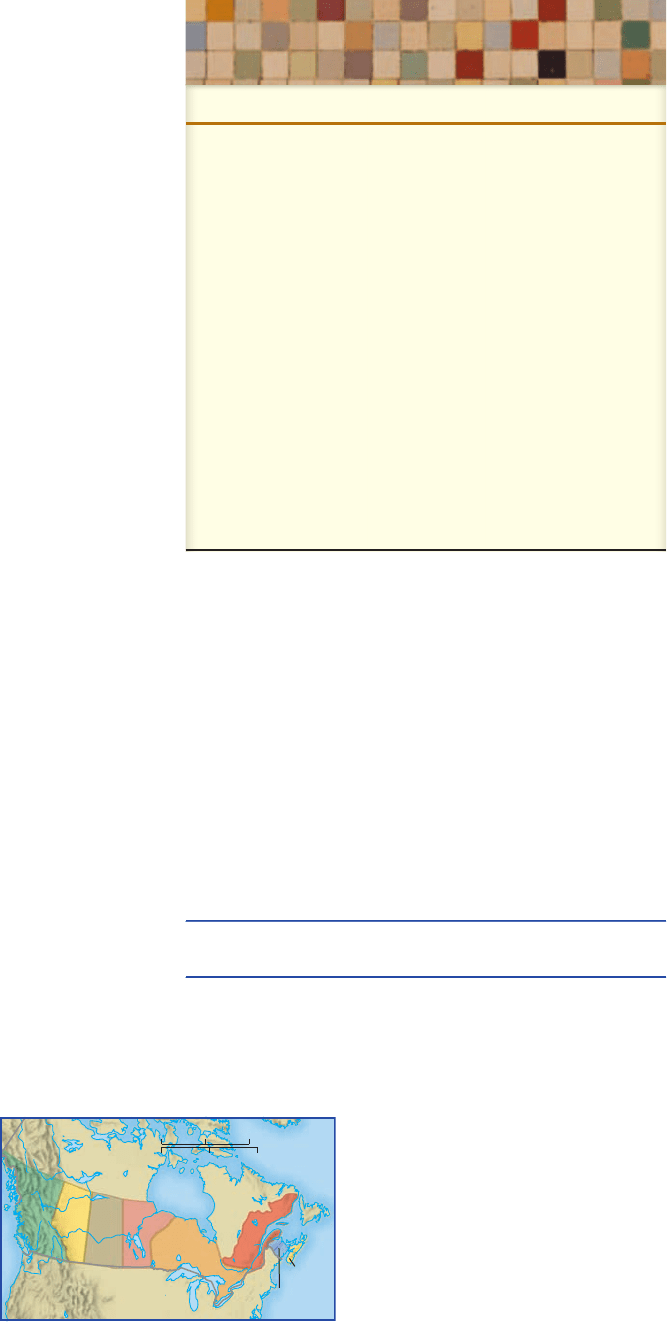

A Midd le-Class Famil y. Nineteenth-century middle-class moralists considered the

family the fundamental pillar of a healthy society. The family was a crucial institution in

middle-class life, and togetherness constituted one of the important ideals of the middle-

class family. This painting by William P. Frith, titled Many Happy Returns of the Day,

shows a family birthday celebration for a little girl in which grandparents, parents, and

children are taking part. The servant at the left holds the presents for the little girl.

c

Harrogate Museums and Art Gallery/The Bridgeman Art Library

THE EMERGENCE OF MASS SOCIETY 501

of women. Suffragists had one basic aim, the right of

women to full citizenship in the nation-state.

The British women’s movement was the most vocal

and active in Europe. Emmeline Pankhurst (1858--1928)

and her daughters, Christabel and Sylvia, founded the

Women’s Social and Political Union in 1903, which en-

rolled mostly middle- and upper-class women. Pank-

hurst’s organization realized the value of the media and

used unusual publicity stunts to call attention to its de-

mands. Derisively labeled ‘‘suffragettes’’ by male politi-

cians, they pelted government officials with eggs, chained

themselves to lampposts, smashed the windows of de-

partment stores on fashionable shopping streets, burned

railroad cars, and went on hunger strikes in jail.

Before World War I, the demands for women’s rights

were being hear d throughout Europe and the United

States, although only in Norway and some American states

did women receive the right to vote before 1914. It would

take the dramatic upheaval of World War I before male-

dominated governments capitulated on this basic issue. At

the same time, at the turn of the twentieth century, a

number of ‘‘new women ’’ became prominent. These

women rejected traditional feminine roles (see the bo x on

p. 503) and sought new freedom outside the household

and new roles other than those of wives and mothers.

Education in an Age of Mass Society

Education in the early nineteenth century was primarily for

the elite or the wealthier middle class, but between 1870 and

1914, most Western governments began to offer at least

primary education to both boys and girls between the ages of

six and twelve. States also assumed responsibility for better

training of teachers by establishing teacher-training schools.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, man y European

states, especially in northern and western Eur ope, were pro-

viding state-financed primary schools, salaried and trained

teachers, and free, compulsory elementary education.

Why did Western nations make this commitment to

mass education? One reason was industrialization. The

new firms of the Second Industrial Revolution demanded

skilled labor. Both boys and girls with an elementary

education had new possibilities of jobs beyond their vil-

lages or small towns, including white-collar jobs in rail-

ways and subways, post offices, banking and shipping

firms, teaching, and nursing. Mass education furnished

the trained workers industrialists needed.

The chief motive for mass education, however, was

political. The expansion of suffrage created the need for a

more educated electorate. Even more important, however,

mass compulsory education instilled patriotism and na-

tionalized the masses, providing an opportunity for even

greater national integration. As people lost their ties to

local regions and even to religion, nationalism supplied

a new faith (see the comparative essay ‘‘The Rise of

Nationalism’’ on p. 504).

Compulsory elementary education created a demand

for teachers, and most of them were women. Many men

viewed the teaching of children as an extension of wom-

en’s ‘‘natural role’’ as nurturers of children. Moreover, fe-

males were paid lower salaries, in itself a considerable

incentive for governments to encourage the establishment

of teacher-training institutes for women. The first female

colleges were really teacher-training schools. It was not

until the beginning of the twentieth century that women

were permitted to enter the male-dominated universities.

Leisure in an Age of Mass Society

With the Industrial Revolution came new forms of lei-

sure. Work and leisure became opposites as leisure came

to be viewed as what people do for fun after work. The

new leisure hours created by the industrial system---

evening hours after work, weekends, and later a week or

two in the summer---largely determined the contours of

the new mass leisure.

New technology created novel experiences for leisure,

such as the Ferris wheel at amusement parks, while the

subways and streetcars of the 1880s meant that even the

working classes were no longer dependent on neighbor-

hood facilities but could make their way to athletic

games, amusement parks, and dance halls. Railroads

could take people to the beaches on weekends.

By the late nineteenth century, team sports had also

developed into another important form of mass leisure.

Unlike the old rural games, they were no longer chaotic

and spontaneous activities but became strictly organized

with sets of rules and officials to enforce them. These

rules were the products of organized athletic groups, such

as the English Football Association (1863) and the

American Bowling Congress (1895). The development of

urban transportation systems made possible the con-

struction of stadiums where thousands could attend,

making mass spectator sports into a big business.

Cultural Life: Romanticism and

Realism in the Western World

Q

Focus Question: What were the main characteristics of

Romanticism and Realism?

At the end of the eighteenth century, a new intellectual

movement known as Romanticism emerged to challenge

the ideas of the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment

stressed reason as the chief means for discovering truth.

502 CHAPTER 20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

OPPOSING VIEWPOINTS

A

DVICE TO WOMEN:TWO V IEWS

Industrialization had a strong impact on middle-

class women as strict gender-based social roles

became the norm. Men worked outside the home

to support the family, while women provided for

the needs of their children and husband at home. In the first

selection, Woman in Her Social and Domestic Character

(1842), Elizabeth Poole Sanford gives advice to middle-class

women on their proper role and behavior.

Although a majority of women probably followed the

nineteenth-century middle-class ideal, an increasing number of

women fought for women’s rights. The second selection is

taken from the third act of Henrik Ibsen’s 1879 play A Doll’s

House, in which the character Nora Helmer declares her inde-

pendence from her husband’s control.

Elizabeth Poole Sanford, Woman in Her Social

and Domestic Character

The changes w rought by Time are many. ...

It is thus that the sentiment for woman has undergone a

change. The romantic passion which once almost deified her is on

the decline; and it is by intrinsic qualities that she must now inspire

respect. She is no longer the queen of song and the star of chivalry.

But if there is less of enthusiasm entertained for her, the sentiment

is more rational, and, perhaps, equally sincere; for it is in relation to

happiness that she is chiefly appreciated.

And in this respect it is, we must confess, that she is most use-

ful and most important. Domestic life is the chief source of her

influence; and the greatest debt society can owe to her is domestic

comfort. ... A woman may make a man’s home delightful, and may

thus increase his motives for virtuous exertion. She may refine and

tranquilize his mind---may turn away his anger or allay his grief. Her

smile may be the happy influence to gladden his heart, and to dis-

perse the cloud that gathers on his brow. And in proportion to her

endeavors to make those around her happy, she will be esteemed

and loved. She w ill secure by her excellence that interest and that re-

gard which she might formerly claim as the privilege of her sex, and

will really merit the deference which was then conceded to her as a

matter of course. ...

Nothing is so likely to conciliate the affections of the other sex

as a feeling that woman looks to them for support and guidance. In

proportion as men are themselves superior, they are accessible to

this appeal. On the contrary, they never feel interested in one who

seems disposed rather to offer than to ask assistance. There is, in-

deed, something unfeminine in independence. It is contrary to

nature, and therefore it offends. We do not like to see a woman

affecting tremors, but still less do we like to see her acting the ama-

zon. A really sensible woman feels her dependence. She does what

she can; but she is conscious of inferiority, and therefore grateful

for support. She knows that she is the weaker vessel, and that as

such she should receive honor. In this view, her weakness is an

attraction, not a blemish.

Henrik Ibsen, A Doll’s House

NORA: Yes, it’s true, Torvald. When I was living at home with Father,

he told me his opinions and mine were the same. If I had dif-

ferent opinions, I said nothing about them, because he would not

have liked it. He used to call me his doll-child and played with

me as I played with my dolls. Then I came to live in your house.

H

ELMER: What a way to speak of our marriage!

N

ORA (Undisturbed): I mean that I passed from Father’s hands into

yours. You arranged everything to your taste and I got the same

tastes as you; or pretended to---I don’t know which---both, per-

haps; sometimes one, sometimes the other. When I look back on

it now, I seem to have been living here like a beggar, on handouts.

I lived by performing tricks for you, Torvald. ... I must stand

quite alone if I am ever to know myself and my surroundings;

so I cannot stay with you.

H

ELMER: You are mad! I shall not allow it! I forbid it!

N

ORA: It’s no use your forbidding me anything now. I shall take with

me only what belongs to me; from you I will accept nothing,

either now or later. ...

H

ELMER: Forsake your home, your husband, your children! And you

don’t consider what the world will say.

N

ORA: I can’t pay attention to that. I only know that I must do it.

H

ELMER: This is monstrous! Can you forsake your holiest duties?

N

ORA: What do you consider my holiest duties?

H

ELMER: Need I tell you that? Your duties to your husband and

children.

N

ORA: I have other duties equally sacred.

H

ELMER: Impossible! What do you mean?

N

ORA: My duties toward myself.

H

ELMER: Before all else you are a wife and a mother.

N

ORA: That I no longer believe. Before all else I believe I am a human

being just as much as you are---or at least that I should try to

become one. I know that most people agree w ith you, Torvald,

and that they say so in books. But I can no longer be satisfied

with what most people say and what is in books. I must think

things out for myself and try to get clear about them.

Q

According to Elizabeth Sanford, what is the proper role of

women? What forces in nineteenth-century European society

merged to shape Sanford’s understanding of ‘‘proper’’ gender

roles? In Ibsen’s play, what challenges does Nora Helmer make

to Sanford’s view of the proper role and behavior of wives?

Why is her husband so shocked? Why did Ibsen title this play

A Doll’s House?

CULTURAL LIFE:ROMANTICISM AND REALISM IN THE WESTERN WORLD 503

Although the Romantics by no means disparaged reason,

they tried to balance its use by stressing the importance of

feeling, emotion, and imagination as sources of knowing.

The Characteristics of Romanticism

Many Romantics had a passionate interest in the past. They

revived medieval Gothic architecture and left European

countrysides adorned with pseudo-medieval castles and

cities bedecked with grandiose neo-Gothic cathedrals, city

halls, and parliamentary buildings. Literature, too, reflected

this historical consciousness. The novels of Walter Scott

(1771--1832) became European best-sellers in the first half

of the nineteenth century. One of the most popular was

Ivanhoe, in which Scott tried to evoke the clash between

Saxon and Norman knights in medieval England.

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

T

HE RISE OF NATIONALISM

Like the Industrial Revolution, the concept of na-

tionalism originated in eighteenth-century Europe,

where it was the product of a variety of factors, in-

cluding the spread of printing and the replacement

of Latin with vernacular languages, the secularization of the

age, and the experience of the French revolutionary and Napo-

leonic eras. The French were the first to show what a nation in

arms could accomplish, but peoples conquered by Napoleon

soon created their own national

armies. At the beginning of the nine-

teenth century, peoples who had pre-

viously focused their identity on a

locality or a region, on loyalty to a

monarch or to a particular religious

faith, now shifted their political alle-

giance to the idea of a nation, based

on ethnic, linguistic, or cultural fac-

tors. The idea of the nation had ex-

plosive consequences: by the end of

the first two decades of the twentieth

century, the world’s three largest

multiethnic states—imperial Russia,

Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman

Empire—had all given way to a num-

ber of individual nation-states.

The idea of establishing political bound-

aries on the basis of ethnicity, language,

or culture had a broad appeal through-

out Western civilization, but it had un-

intended consequences. Although the

concept provided the basis for a new

sense of community that was tied to

liberal thought in the first half of the

nineteenth century, it also gave birth to ethnic tensions and hatred

in the second half of the century that resulted in bitter disputes and

contributed to the competition between nation-states that eventually

erupted into world war. Governments, following the lead of the rad-

ical government in Paris during the French Revolution, took full

advantage of the rise of a strong national consciousness and trans-

formed war into a demonstration of national honor and commit-

ment. Universal schooling enabled states to arouse patriotic

enthusiasm and create national unity. Most soldiers who joyfully

went to war in 1914 were convinced that their nation’s cause

was just.

But if the concept of nationalism was initially the product of

conditions in modern Europe, it soon spread to other parts of the

world. Although a few societies, such

as Vietnam, had already developed a

strong sense of national identity, most

of the peoples in Asia and Africa lived

in multiethnic and multireligious

communities and were not yet ripe

for the spirit of nationalism. As we

shall see, the first attempts to resist

European colonial rule were thus

often based on religious or ethnic

identity, rather than on the concept of

denied nationhood. But the imperial-

ist powers, which at first benefited

from the lack of political cohesion

among their colonial subjects, eventu-

ally reaped what they had sowed. As

the colonial peoples became familiar

with Western concepts of democracy

and self-determination, they too

began to manifest a sense of common

purpose that helped knit together the

different elements in their societies to

oppose colonial regimes and create

the conditions for the emergence of

future nations. For good or ill, the

concept of nationalism had now

achieved global proportions. We shall explore such issues, and their

consequences, in greater detail in the chapters that follow.

Q

What is nationalism? How did it arise, and what impact did it

have on the history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries?

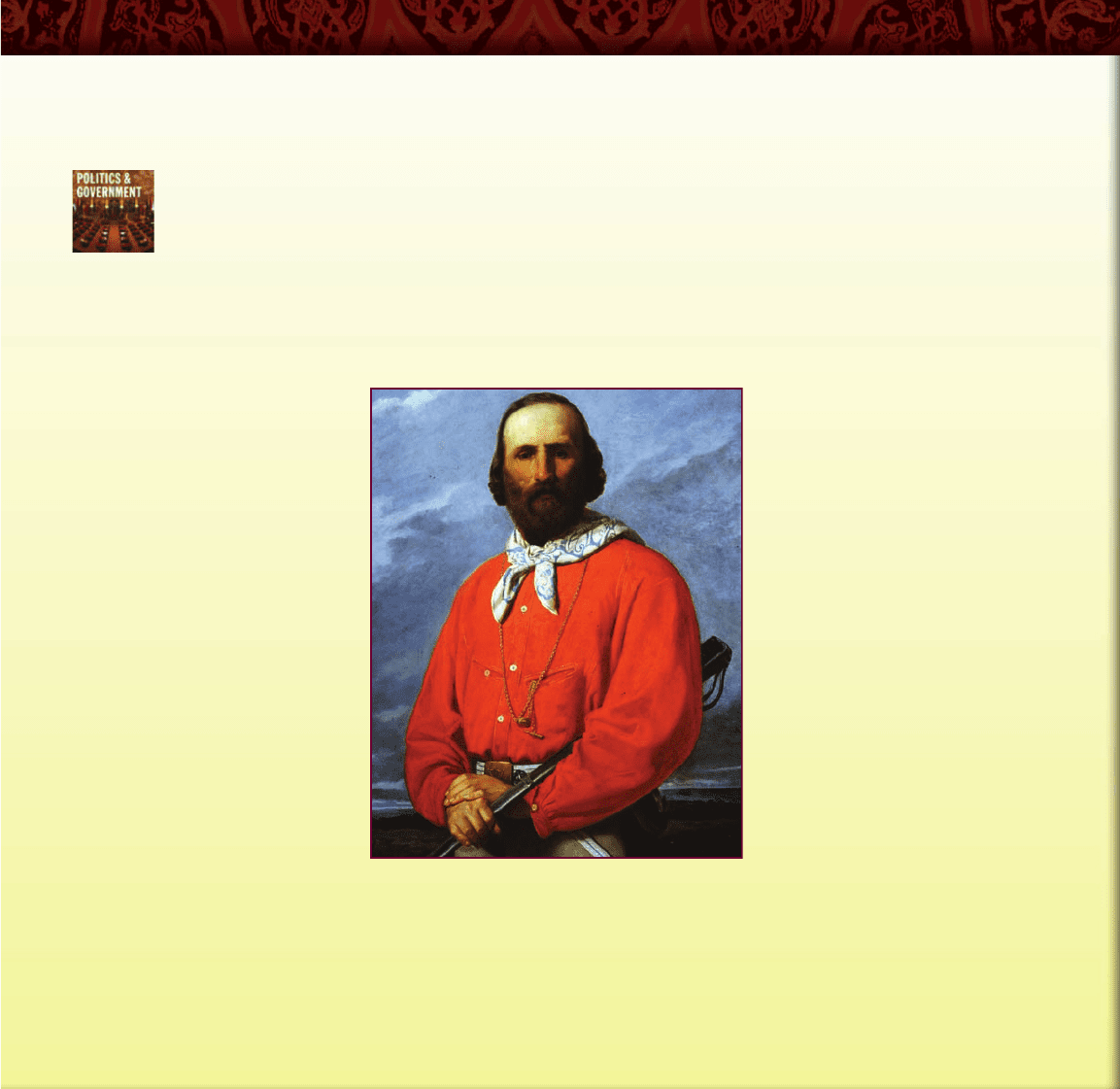

Garibaldi. Giuseppe Garibaldi was a dedicated patriot and

an outstanding example of the Italian nation alism that led

to the unification of Italy by 1870.

c

The Art Archive/Museo Civico, Modigliana, Italy/Alfredo Dagli Orti

504 CHAPTER 20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

Many Romantics had a deep attraction to the exotic

and unfamiliar. In an exaggerated form, this preoccupa-

tion gave rise to so-called Gothic literature, chillingly

evident in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Edgar Allan

Poe’s short stories of horror (see the box above). Some

Romantics even brought the unusual into their own lives

by experimenting with cocaine, opium, and hashish in an

attempt to find extraordinary experiences through drug-

induced altered states of consciousness.

To the Romantics, poetry was the direct expression of

the soul and therefore ranked above all other literary

forms. Romantic poetry gave full expression to one of the

most important characteristics of Romanticism: love of

nature, especially evident in the poetry of William

Wordsworth (1770--1850). His experience of nature was

almost mystical as he claimed to receive ‘‘authentic tidings

of invisible things’’:

One impulse from a vernal wood

May teach you more of man,

Of Moral Evil and of good,

Than all the sages can.

6

Romantics believed that nature served as a mirror into

which humans could look to learn about themselves.

Like the literary arts, the visual arts were also deeply

affected by Romanticism. To Romantic artists, all artistic

expression was a reflection of the artist’s inner feelings; a

painting should mirror the artist’s vision of the world and

be the instrument of his own imagination.

Eug

ene Delacroix (1798--1863) was one of the most

famous French exponents of the Romantic school of

painting. Delacroix visited North Africa in 1832 and was

strongly impressed by its vibrant colors and the brilliant

dress of the people. His paintings came to exhibit two

primary characteristics, a fascination with the exotic and a

passion for color. Both are apparent in his Women of Al-

giers. In Delacroix, theatricality and movement combined

with a daring use of color. Many of his works reflect his

own belief that ‘‘a painting should be a feast to the eye.’’

GOTHIC LITERATURE:EDGAR ALLAN POE

American writers and poets made significant contri-

butions to the movement of Romanticism. Although

Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) was influenced by

the German Romantic school of mystery and hor-

ror, many literary historians give him the credit for pioneering

the modern short story. This selection from the conclusion of

‘‘The Fall of the House of Usher’’ gives a feeling for the nature

of so-called Gothic literature.

Edgar Allan Poe, ‘‘The Fall of the House of Usher’’

No sooner had these syllables passed my lips, than---as if a shield of

brass had indeed, at the moment, fallen heavily upon a floor of

silver---I became aware of a distinct, hollow, metallic, and clan-

gorous, yet apparently muffled, reverberation. Completely unnerved,

I leaped to my feet; but the measured rocking movement of Usher

was undisturbed. I rushed to the chair in which he sat. His eyes

were bent fixedly before him, and throughout his whole counte-

nance there reigned a stony rigidity. But, as I placed my hand upon

his shoulder, there came a strong shudder over his whole person; a

sickly smile quivered about his lips; and I saw that he spoke in a

low, hurried, and gibbering murmur, as if unconscious of my pres-

ence. Bending closely over him, I at length drank in the hideous

import of his words.

‘‘Not hear it?---yes, I hear it, and have heard it. Long-long-long-

many minutes, many hours, many days, have I heard it---yet I dared

not---oh, pity me, miserable wretch that I am!---I dared not---I dared

not speak! We have put her living in the tomb! Said I not that my

senses were acute? I now tell you that I heard her first feeble move-

ments in the hollow coffin. I heard them---many, many days ago---yet

I dared not---I dared not speak! And now---to-night--- ...the rending

of her coffin, and the grating of the iron hinges of her prison, and

her struggles within the coppered archway of the vault! Oh whither

shall I fly? Will she not be here anon? Is she not hurrying to upbraid

me for my haste? Have I not heard her footstep on the stair?

Do I not distinguish that heavy and horrible beating of her heart?

MADMAN!’’---here he sprang furiously to his feet, and shrieked out

his syllables, as if in the effort he were giving up his soul---‘‘MADMAN!

I TELL YOU THAT SHE NOW STANDS WITHOUT THE DOOR!’’

As if in the superhuman energy of his utterance there had been

found the potency of a spell, the huge antique panels to which the

speaker pointed threw slowly back, upon the instant, their ponder-

ous and ebony jaws. It was the work of the rushing gust---but then

without those doors there DID stand the lofty and enshrouded fig-

ure of the lady Madeline of Usher. There was blood upon her white

robes, and the evidence of some bitter struggle upon every portion

of her emaciated frame. For a moment she remained trembling and

reeling to and fro upon the threshold, then, with a low moaning

cry, fell heavily inward upon the person of her brother, and in her

violent and now final death-agonies, bore him to the floor a corpse,

and a victim to the terrors he had anticipated.

Q

What were the aesthetic aims of Gothic literature? How did

it come to be called ‘‘Gothic’’? How did its values relate to

those of the Romantic movement as a whole?

CULTURAL LIFE:ROMANTICISM AND REALISM IN THE WESTERN WORLD 505