Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

representative assembly (l egislature) elected by qualified

voters. Thus, many liberals believed in a constitutional

monarchy or constitutional state with limi ts on the

powers of government to prevent despotism and in

written constitutions that would guarantee these rights.

Liberals were not democrats, however. They thought

that the right to vote and hold office should be open

only to men of proper ty. As a political philosophy, lib-

erali sm was adopted by middle-class men, espec ially

industrial middle-class men, who favored voting ri ghts

for themselves so that th ey could share power with the

landowning classes.

Nationalism was an even more powerful ideology for

change in the nineteenth century. Nationalism arose out

of an awareness of being part of a community that has

common institutions, traditions, language, and customs.

This community is called a nation, and the primary po-

litical loyalty of individuals would be to the nation. Na-

tionalism did not become a popular force for change until

the French Revolution. From then on, nationalists came

to believe that each nationality should have its own

government. Thus, the Germans, who were not united,

wanted national unity in a German nation-state with one

central government. Subject peoples, such as the Hun-

garians, wanted the right to establish their own autonomy

rather than be subject to a German minority in the

multinational Austrian Empire.

Nationalism, then, was a threat to the existing po-

litical order. A united Germany, for example, would upset

the balance of power established at Vienna in 1815.

Conservatives feared such change and tried hard to re-

press nationalism. The conservative order dominated

much of Europe after 1815, but the forces of liberalism

and nationalism, first generated by the French Revolu-

tion, continued to grow as that second great revolution,

the Industrial Revolution, expanded and brought in new

groups of people who wanted change. In 1848, these

forces for change erupted.

Nap

ap

ap

p

p

p

p

ap

p

p

p

les

les

le

les

les

le

les

les

les

le

es

es

p

p

p

p

p

les

le

les

les

es

les

M

osco

w

S

aint Petersburg

W

arsa

w

Ber

lin

r

li

rli

Ver

Ver

Ver

V

Ver

Ver

Ver

Ver

Ver

Ver

er

on

n

na

n

na

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

Ver

Ver

Ve

Ver

Ver

Ver

Ver

e

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

a

a

Vienna

Vienn

Laibach

ai

ai

L

L

L

Lon

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

don

L

L

L

L

L

L

P

aris

Bud

a

M

ad

ri

d

L

y

o

ns

s

ns

ns

ns

s

s

ns

s

s

s

s

s

Rom

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

m

m

m

m

m

e

e

e

Lis

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

b

b

b

bon

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

B

B

B

a

a

l

l

l

e

e

a

a

r

r

i

i

i

c

c

I

I

I

s

s

I

I

I

I

l

l

l

a

a

n

n

d

d

d

s

d

d

Cor

C

Cor

Cor

Cor

Cor

Cor

Cor

Cor

Cor

Cor

C

r

Cor

C

Cor

r

Cor

C

C

C

sic

ic

a

a

Cor

C

CorCor

r

Cor

C

Cor

Cor

C

Cor

r

Cor

C

r

Cor

Cor

C

C

Cre

Cr

C

Cre

Cr

Cre

C

CreCre

C

Cre

Cr

C

Cr

Cr

C

te

te

te

te

te

te

te

te

t

te

te

e

e

Cre

Cre

Cre

Cr

C

CrCr

Cr

Cre

C

te

te

te

te

te

te

te

te

t

e

e

Cyp

Cyp

Cyp

Cyp

Cyp

yp

Cyp

Cyp

Cy

Cyp

C

Cy

rus

us

us

us

rus

us

s

u

us

us

s

u

ru

u

Cyp

Cyp

Cyp

Cyp

Cyp

Cyp

Cyp

Cy

Cyp

rus

us

us

rus

rus

u

us

us

P

y

P

r

e

r

n

e

e

s

T

a

T

T

u

r

u

r

r

s

M

t

M

M

s

t

t

.

A

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

Elb

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

a

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

Me

M

M

M

diterranea

n

M

M

S

ea

Atla

n

tic

O

cea

n

Nort

h

Sea

Black Se

a

B

a

l

t

l

i

tt

c

S

e

a

R

R

h

h

i

n

n

n

n

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

R

.

E

E

b

r

b

b

o

r

r

R

R

R

.

.

P

o

D

a

a

n

n

u

u

b

e

R

R

.

D

n

i

e

p

e

e

r

R

.

D

n

i

e

s

t

e

t

t

r

R

.

D

a

n

u

n

n

b

e

b

R

.

D

o

n

o

R

.

P

PO

POR

OR

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

TUG

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

AL

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

S

PAIN

F

RAN

C

E

GR

R

RE

RE

RE

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

AT

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

RR

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

B

B

BRI

BRI

BRI

BRI

I

B

B

B

BRI

I

I

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

TAI

I

I

I

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

I

I

I

I

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

B

BRI

BRI

BRI

BRI

I

BRI

BRI

B

B

B

B

D

DE

E

EN

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

MAR

MAR

A

MAR

MAR

AR

A

A

AR

A

A

MAR

MAR

MAR

A

A

MAR

A

MAR

R

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

MA

MAR

MAR

A

A

A

A

A

MA

MA

MA

A

M

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

M

A

A

A

A

A

NET

N

N

H.

N

N

N

N

N

S

S

W

SW

W

SW

S

SW

SW

SW

SWI

SW

I

SW

I

I

I

S

SW

W

S

S

TZ

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z.

Z

Z

TZ

TZ

T

Z

Z

Z

T

TZ

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z.

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z.

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

TZ

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

WI

I

I

I

I

I

TZ

TZ

TZ

Z

TZ

T

TZ

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

WITZ

P

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

UU

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

S

S

I

I

I

A

A

A

LOM

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

B

B

B

B

BAR

B

B

BAR

BAR

BAR

BAR

AR

BAR

R

BA

R

BAR

R

A

R

B

R

BAR

BAR

AR

AR

BAR

R

B

R

R

AR

R

AR

B

AR

AR

AR

BAR

AR

BAR

A

AR

A

R

A

A

A

A

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

Y

Y

DY

Y

D

Y

Y

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

BAR

BAR

BAR

BAR

BAR

AR

R

R

BAR

R

AR

R

R

AR

AR

AR

AR

R

R

BAR

R

R

AR

R

AR

BAR

R

AR

AR

AR

R

BAR

AR

BAR

B

AR

A

R

A

A

A

B

B

B

B

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

DY

DY

DY

Y

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DY

DYDY

D

DY

DY

DY

Y

DY

Y

Y

Y

VEN

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

ETIA

V

V

V

V

PA

A

A

AR

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

MA

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

P

MA

MA

MA

MA

MA

A

MA

M

MA

A

MA

MA

A

A

MA

A

A

A

A

MA

A

A

A

A

A

AR

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

AR

A

A

A

R

M

M

M

M

M

M

MA

MA

MA

A

A

A

M

M

M

MA

MOD

MOD

MOD

MOD

MOD

MOD

O

OD

OD

D

D

D

D

D

D

OD

OD

O

O

D

D

D

D

O

MOD

MOD

MOD

MOD

O

O

MOD

D

O

OD

O

OD

O

OD

MO

D

O

D

O

O

O

O

O

E

E

E

E

ENA

ENA

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

NA

NA

NA

E

E

E

NA

NA

NA

E

E

NA

NA

E

E

NA

E

A

A

E

NA

A

NA

NA

E

E

NA

NA

A

NA

NA

A

A

NA

A

NA

NA

NA

NA

N

NA

N

N

M

M

M

M

M

M

A

MOD

MOD

MOD

MOD

MOD

OD

OD

O

O

O

D

MOD

OD

OD

O

O

D

O

O

MOD

O

MOD

O

OD

D

O

O

O

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

M

M

M

M

M

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

E

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

TUSTUS

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

CA

CA

C

C

C

C

A

CAN

CA

AN

AN

AN

N

N

N

N

N

CA

C

C

C

CA

N

N

A

CA

A

N

C

A

N

CA

C

CA

A

N

N

N

C

C

C

N

N

C

C

A

N

C

N

N

N

N

C

N

N

N

N

A

N

A

A

N

A

A

N

N

N

A

Y

T

T

T

T

T

T

CA

A

A

C

A

CA

CA

CA

A

A

A

A

CA

A

A

A

CA

A

CA

A

C

CA

A

A

C

C

CA

C

C

CA

ACA

C

C

A

C

C

CA

C

A

CA

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

KIN

N

N

N

N

N

N

KIN

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

O

O

GD

O

O

GD

GDO

GD

DO

O

O

O

O

DO

O

DO

D

M O

M O

M O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

M O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

M O

O

O

O

O

O

O

M O

M O

M O

O

O

O

O

O

O

MO

MO

M O

MO

MO

M

O

M

M

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

O

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

O

GDO

DO

GD

GDO

GD

DO

O

O

O

M O

M O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

M O

O

O

O

O

M O

O

O

O

M O

M O

O

O

O

O

MO

O

MO

MO

M O

MO

MO

M O

M

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

SA

SA

A

A

SAR

R

SA

SA

SA

A

A

A

A

SA

SA

SA

R

S

A

A

DIN

DIN

IN

DI

IA

IA

IA

SA

A

A

A

A

A

SA

SA

SA

A

SA

(

(

(

(PI

(PI

(

(P

(

(

(

(

(

PI

E

ED

EDM

ON

NT

T

T

)

(

(

(P

(

(

(

(

(

(

(

KIN

IN

N

GDO

GDO

DO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

D

DO

GDO

M O

MO

MO

M O

M O

MO

M O

M OM O

M O

M O

MO

F

GDO

GDO

GDO

DO

GDO

GDO

GDO

GDO

M O

M O

MO

M O

M O

M O

M O

MO

M

TH

THE

THE

E

TW

TW

TW

TW

TW

T

TW

TW

TW

TW

TW

T

O

O

O

TW

TW

TW

W

TW

TW

TW

TW

SICSIC

SIC

IC

SIC

SIC

SIC

SIC

SIC

SIC

SIC

ILIILI

IL

IL

IL

IL

IL

IL

IL

L

IL

IL

E

E

ES

ES

SIC

IC

C

SIC

C

C

SIC

C

C

I

I

I

I

I

I

IL

IL

L

L

IL

IL

IL

IL

O

TTOMAN

E

MPIRE

A

U

S

S

T

R

T

T

I

RR

A

N

E

M

E

E

P

MM

I

PP

R

II

E

E

RR

RUSSIAN EMPIRE

PI

IA

KIN

GDO

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

M O

F

F

G

G

G

G

G

G

NOR

NOR

NOR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

NOR

R

WA

W

WA

WA

WAY

WAY

W

WA

W

W

A

A

A

AN

A

A

A

A

A

D S

WED

ED

ED

ED

ED

ED

ED

ED

ED

D

D

E

E

E

EN

EN

N

E

E

N

A

A

A

A

A

A

WED

E

WED

ED

ED

ED

D

D

E

E

E

E

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

WA

WA

WA

WA

W

W

A

A

GER

GER

GER

GER

GER

ER

E

R

ER

E

G

ER

E

ER

ER

ER

R

E

G

MAN

IC

R

ER

ER

ER

ER

R

R

ER

ERER

R

ER

ER

ER

ER

ER

R

E

E

M

G

GG

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

C

CON

FED

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

ERA

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

TIO

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

E

E

E

E

E

C

C

PAP

P

P

P

A

A

A

AL

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

L

A

P

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

P

A

A

A

A

P

A

TE

TE

E

TES

TES

S

TE

TE

TE

T

TE

E

TE

TE

TE

TE

TE

STA

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

T

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

A

SA

SA

SAX

SA

SA

SAX

SAX

SA

X

X

X

SA

SA

AX

SAX

SAX

AX

SAX

SAX

SAX

AX

X

X

SA

A

SAX

X

X

SA

SA

X

S

S

SA

A

SA

SAX

S

A

S

S

S

ONY

ON

ON

ON

O

ON

ON

O

ON

ON

ON

ON

O

O

O

ON

O

O

O

ON

ON

O

ON

ON

ON

O

X

X

X

X

X

X

A

X

AX

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

O

ON

O

ON

ON

O

ON

ON

ON

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

ON

O

SA

SA

SA

SA

S

SA

A

A

S

S

SA

SA

SA

SA

A

SA

S

SA

S

KINGDO

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

O

OF

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

POL

OL

OL

OL

O

OL

OL

OL

OL

OL

OL

L

O

OL

O

OL

L

O

O

O

L

L

O

O

O

O

AND

D

D

D

AND

D

D

D

AND

AND

D

N

N

N

N

ND

AND

N

N

ND

AND

AND

AN

N

N

ND

AN

D

AND

N

N

ND

AND

ND

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

D

N

N

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

0

25

250

50

0

5

0

0

0

00

00 00

00

0

00

0

0

00

0

0

0

M

M

M

M

Mil

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

es

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

0

0

00

00

0

00

00

0

00

0

250

5

00

7

7

50

50

0

0

0

0

0

Kil

Ki

Ki

K

Kil

K

Kil

Kil

Kil

Kil

Kil

Ki

Kil

K

Ki

Kil

Kil

K

Kil

Kil

Kil

K

Kil

Kil

Ki

K

Ki

K

K

ome

o

o

ter

s

s

Ki

Ki

Ki

Ki

Ki

Ki

Ki

Ki

Ki

K

K

Ki

Kil

Kil

KilKilKil

Kil

Kil

K

K

Kil

Kil

Ki

i

oo

o

o

s

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

0

0

0

0

0

0

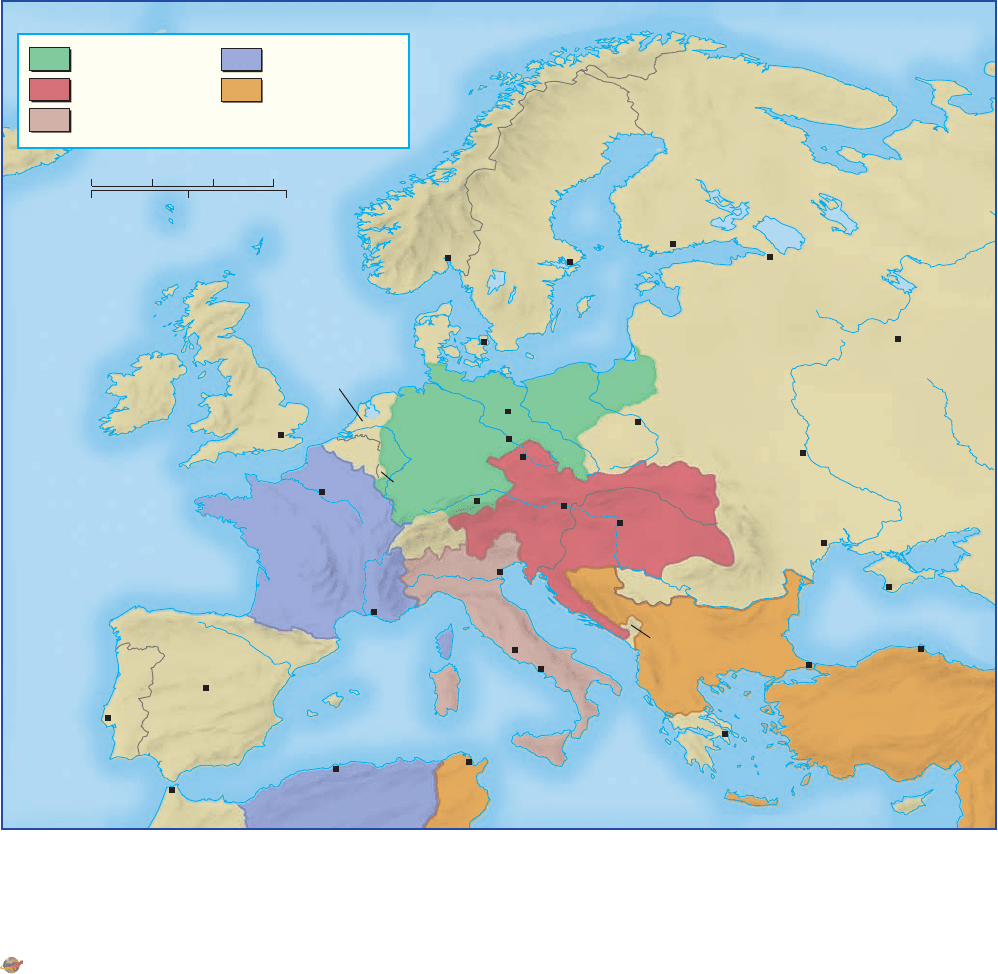

Boundary of the Germanic Confederation

Prussia

Austrian Empire

Kingdom of Sardinia

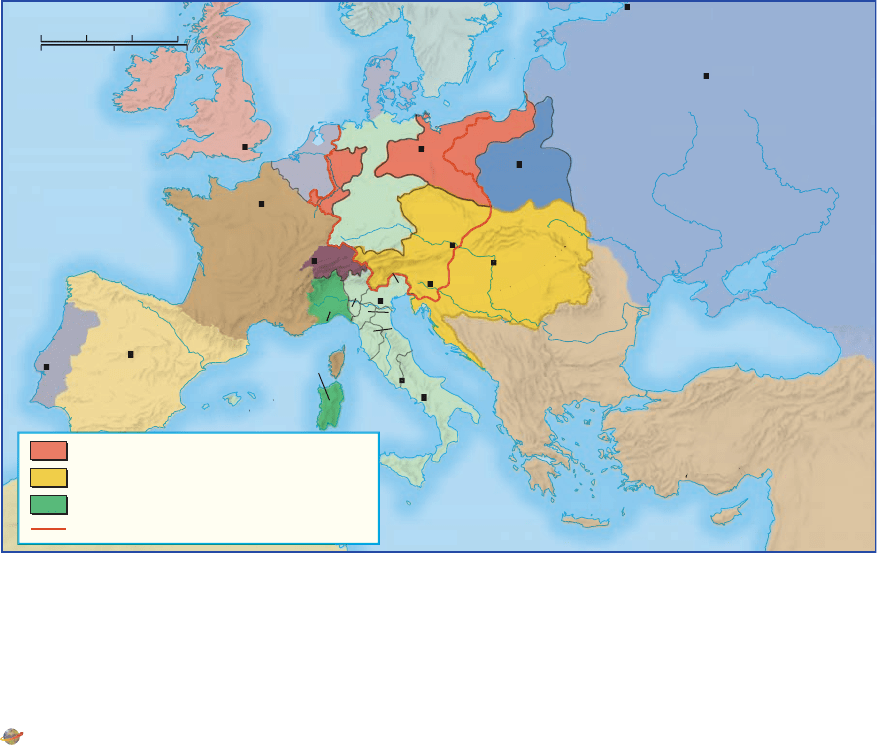

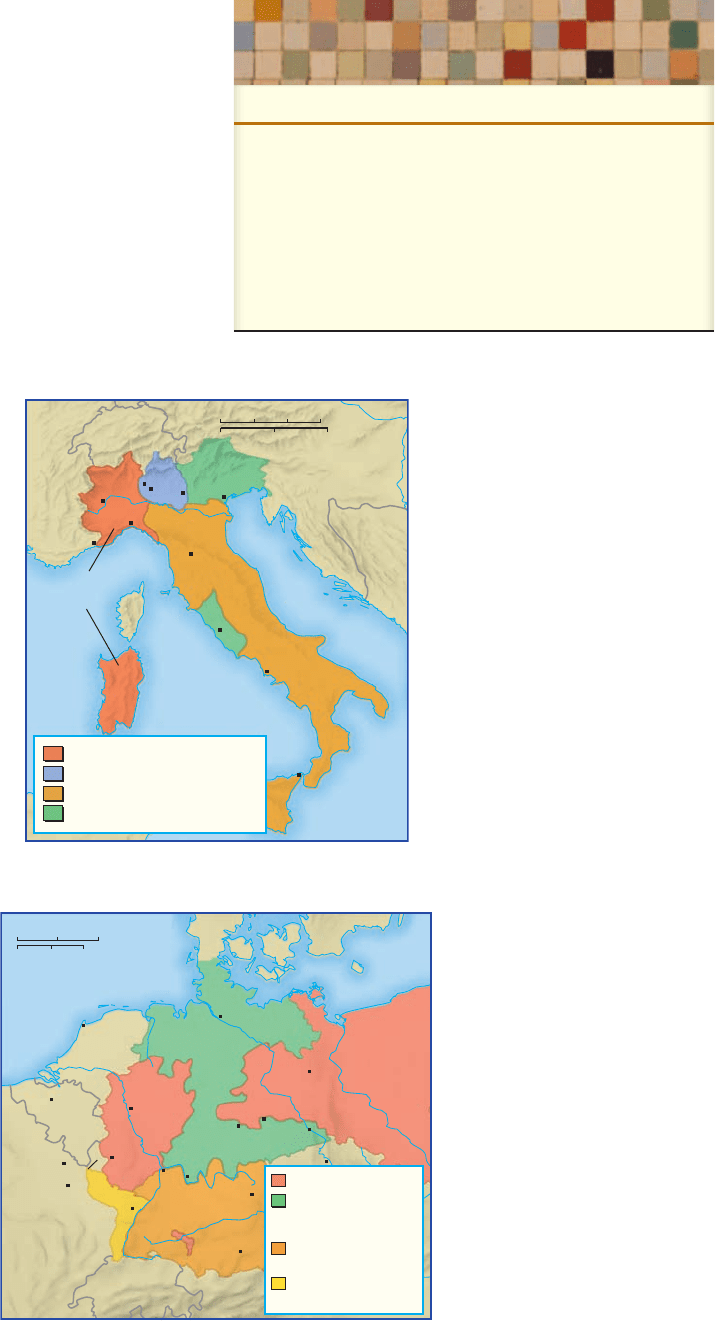

MAP 19.2 Europe After the Congress of Vienna, 1815. The Congress of Vienna

imposed order on Europe based on the principles of monarchical government and a balance

of powe r. Monarchs were restored in France, Spain, and other states recently under

Napoleon’s control, and much territory changed hands, often at the expense of small and

weak states.

Q

How did Europe ’s major powers manipulate territory to decrease the probability that

France could again threaten the Continent’s stability?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www .c engage.c om/hist ory/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

476 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

The Revolutions of 1848

Rev olution in France was the spark for revolution in other

countries. Beginning in 1846, a sever e industrial and ag-

ricultural depression in France brought untold hardship to

the lower middle class, work ers, and peasants, while the

government ’s persistent refusal to lower the property

qualification for voting angered the disenfranchised

members of the middle class. When the government of

King Louis-Philippe (1830--1848) refused to make changes,

opposition grew and finally overthrew the monarchy on

February 24, 1848. A group of moderate and radical re-

publicans established a provisional government and called

for the election by universal male suffrage of a ‘‘c onstituent

assembly’’ that would draw up a new constitution.

The new constitution, ratified on November 4, 1848,

established a republic (the Second Republic) with a single

legislature elected to three-year terms by universal male

suffrage and a president elected to a four-year term, also

by universal male suffrage. In the elections for the pres-

idency held in December 1848, Charles Louis Napoleon

Bonaparte, the nephew of the famous French ruler, won a

resounding victory.

News of the 1848 revolution in France led to up-

heaval in central Europe as well (see the box on p. 478).

The Vienna settlement in 1815 had recognized the exis-

tence of thirty-eight sovereign states (called the Germanic

Confederation) in what had once been the Holy Roman

Empire. Austria and Prussia were the two great powers in

terms of size and might; the other

states varied considerably. In 1848,

cries for change caused many German

rulers to promise constitutions, a free

press, jury trials, and other liberal re-

forms. In Prussia, King Frederick

William IV (1840--1861) agreed to es-

tablish a new constitution and work

for a united Germany.

The promise of unity rev erberated

throughout all the German states as

governments allowed elections by uni-

versal male suffrage for deputies to

an all-German parliament called the

Frankfurt Assembly . Its purpose was to

fulfill a liberal and nationalist dream---

the preparation of a constitution for a

new united Germany. But the Frankfurt

Assembly failed to achieve its goal. The

members had no real means of com-

pelling the German rulers to accept the

constitution they had drawn up. Ger-

man unification was not achieved; the

revolution had failed.

The Austrian Empire needed only the news of the

revolution in Paris to erupt in flames in Mar ch 1848. The

Austrian Empire was a multinational state, a collection

of at least eleven ethnically distinct peoples, including

Germans, Czechs, Magyars (H ungarians), Slovaks, Roma-

nians, Serbians, and Italians, who had pledged their loyalty

to the Habsburg emperor. The Germans, though only a

quarter of the population, were economically dominant

and pla yed a leading role in gov erning Austria. In March,

demonstrations in Buda, Prague, and Vienna led to the

dismissal of Metternich, the Austrian foreign minister and

the archsymbol of the conservativ e order, who fled abroad.

In Vienna, revolutionary forces took control of the capital

and demanded a liberal constitution. Hungary was given

its own legislature and a separate national army.

Austrian officials had made concessions to appease

the revolutionaries, but they were determined to rees-

tablish firm control. As in the German states, they were

increasingly encouraged by the divisions between radical

and moderate revolutionaries. By the end of October

1848, Austrian military forces had crushed the radical

rebels in Vienna, but it was only with the assistance of

a Russian army of 140,000 men that the Hungarian rev-

olution was finally put down in 1849. The revolutions in

the Austrian Empire had failed.

So did revolutions in Italy. The Congress of Vienna

had established nine states in Italy, including the Kingdom

of Sardinia in the north, ruled by the house of Savoy; the

Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Naples and Sicily); the Papal

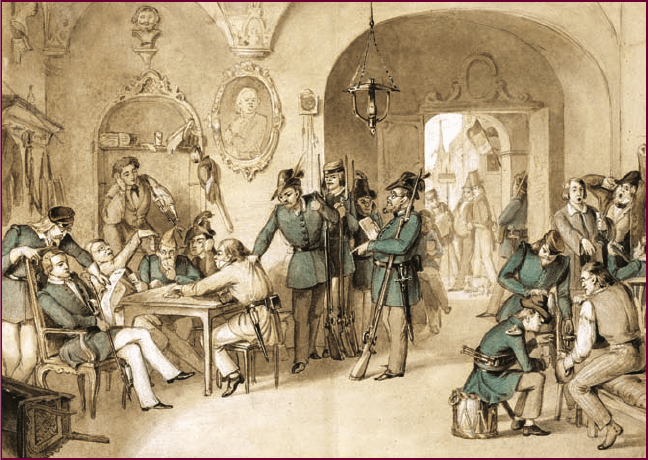

Austrian Students in the Revo lutionary Civi l G uard. In 1848, revolutionary fervor swept

the European continent and toppled governments in France, central Europe, and Italy. In the

Austrian Empire, students joined the revolutionary civil guard in taking control of Vienna and

forcing the Austrian emperor to call a constituent assembly to draft a liberal constitution.

c

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

REACTION AND REVOLUTION:THE GROWTH O F NATIONALISM 477

OPPOSING VIEWPOINTS

R

ESPONSE TO REVOLUTION:TWO PERSPECTIVES

Based on their po litical belie fs, European s

responded differently to the specter of revolution

that ha unte d Europe in the first ha lf of the n ine -

teenth cen tury. The first excerpt is taken from a

speech given by Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800–1859), a

historian and a member of t he British Parliamen t. Macaul ay

spoke in Parliament on behalf of the Reform Act of 1832,

which extended the right to vote to the industrial middle

classes of Britain. A revolution in France in 1830 that had

resulted in some gains for the uppe r bourgeoi sie had influ-

enced his belief that it was be tter to reform than to have

a political revolution.

The second excerpt is taken from the Reminiscences of

Carl Schurz (1829–1906). Like many liberals and nationalists

in Germany, Schurz received the news of the February Revolu-

tion of 1848 in France with much excitement and great expecta-

tions for revolutionary change in the German states. After the

failure of the German revolution, Schurz made his way to the

United States and eventually became a U.S. senator.

Thomas Babington Macaulay,

Speech of March 2, 1831

My hon[orable] friend the member of the University of Oxford tells

us that, if we pass this law, England will soon be a Republic. The re-

formed House of Commons will, according to him, before it has sat

ten years, depose the King, and expel the Lords from their House.

Sir, if my hon[orable] friend could prove this, he would have suc-

ceeded in bringing an argument for democracy infinitely stronger

than any that is to be found in the works of [Thomas] Paine. His

proposition is, in fact, this---that our monarchical and aristocratical

institutions have no hold on the public mind of England; that these

institutions are regarded with aversion by a decided majority of the

middle class. ... Now, sir, if I were convinced that the great body of

the middle class in England look with aversion on monarchy and ar-

istocracy, I should be forced, much against my will, to come to this

conclusion, that monarchical and aristocratical institutions are un-

suited to this country. Monarchy and aristocracy, valuable and useful

as I think them, are still valuable and useful as means, and not as

ends. The end of government is the happiness of the people; and I

do not conceive that, in a country like this, the happiness of the

people can be promoted by a form of government in which the

middle classes place no confidence, and which exists only because

the middle classes have no organ by which to make their sentiments

known. But, sir, I am fully convinced that the middle classes sin-

cerely wish to uphold the royal prerogatives, and the constitutional

rights of the Peers. ...

But let us know our interest and our duty better. Turn where

we may---within, around---the voice of great events is proclaiming to

us, ‘‘Reform, that you may preserve.’’ Now, therefore, while every-

thing at home and abroad forebodes ruin to those who persist in a

hopeless struggle against the spirit of the age; now, ...take counsel,

not of prejudice, not of party spirit ...but of history, of reason,

of the ages which are past, of the signs of this most portentous

time. ... Save property divided against itself. Save the multitude,

endangered by their own ungovernable passions. Save the aristoc-

racy, endangered by its own unpopular power. Save the greatest, and

fairest, and most highly civilized communit y that ever existed, from

calamities which may in a few days sweep away all the rich heritage

of so many ages of wisdom and glory. The danger is terrible. The

time is short. If this Bill should be rejected, I pray to God that

none of those who concur in rejecting it may ever remember their

votes with unavailing regret, amidst the wreck of laws, the confusion

of ranks, the spoliation of property, and the dissolution of social

order.

Carl Schurz, Reminiscences

One morning, toward the end of February, 1848, I sat quietly in my

attic-chamber, working hard at my tragedy of ‘‘Ulrich von Hutten’’

[a sixteenth-century German knight], when suddenly a friend rushed

breathlessly into the room, exclaiming: ‘‘What, you sitting here! Do

you not know what has happened?’’

‘‘No; what?’’

‘‘The French have driven away Louis Philippe and proclaimed

the republic.’’

I threw down my pen---and that was the end of ‘‘Ulrich von

Hutten.’’ I never touched the manuscript again. We tore down the

stairs, into the street, to the market-square, the accustomed meeting-

place for all the student societies after their midday dinner. Although

it was still forenoon, the market was already crowded with young

men talking excitedly. There was no shouting, no noise, only agitated

conversation. What did we want there? This probably no one knew.

But since the French had driven away Louis Philippe and proclaimed

the republic, something of course must happen here, too. ...

The next morning there were the usual lectures to be attended.

But how profitless! The voice of the professor sounded like a monot-

onous drone coming from far away. What he had to say did not

seem to concern us. The pen that should have taken notes remained

idle. At last we closed with a sigh the notebook and went away, im-

pelled by a feeling that now we had something more important to

do---to devote ourselves to the affairs of the fatherland. And this we

did by seeking as quickly as possible again the company of our friends,

in order to discuss what had happened and what was to come.

(continued)

478 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

States; a handful of small duchies; and the important

northern provinces of Lombardy and Venetia, which were

now part of the Austrian Empire. Italy was largely under

Austrian domination, but a new movement for Italian

unity known as Young Italy led to initially successful re-

volts in 1848. By 1849, however, the Austrians had rees-

tablished complete control over Lombardy and Venetia,

and the old order also prevailed in the rest of Italy.

Throughout Eur ope in 1848--1849, moderate, middle-

class liberals and radical workers soon divided over their

aims, and the failure of the revolutionaries to stay united

soon led to the reestablishment of authoritarian regimes.

In other parts of the Western world, rev olutions took

somewhat different directions (see Chapter 20).

Nationalism in the Balkans: The Ottoman

Empire and the Eastern Question

The Ottoman Empire had long been in control of much of

the Balkans in southeastern Europe. By the beginning

of the nineteenth century, however, the Ottoman Empire

was in decline, and authority over its outlying territories

in the Balkans waned. As a result, European governments,

especially those of Russia and Austria, began to take an

active interest in the disintegration of the empire, which

they called the ‘‘sick man of Europe.’’

When the Russians invaded the Ottoman provinces

of Moldavia and Wallachia, the Ottoman Turks declared

war on Russia on October 4, 1853. In the following year,

on March 28, Great Britain and France, fearful of Russian

gains, declared war on Russia. The Crimean War, as the

conflict came to be called, was poorly planned and poorly

fought. Heavy losses caused the Russians to sue for peace.

By the Treaty of Paris, signed in March 1856, Russia

agreed to allow Moldavia and Wallachia to be placed

under the protection of all the great powers.

The Crimean War destroyed the Concert of Europe.

Austria and Russia, the two chief powers maintaining the

status quo in the first half of the nineteenth century, were

now enemies because of Austria’s unwillingness to sup-

port Russia in the war. Russia, defeated and humiliated by

the obvious failure of its armies, withdrew from European

affairs for the next two decades. Great Britain, disillu-

sioned by its role in the war, also pulled back from

continental affairs. Austria, paying the price for its neu-

trality, was now without friends among the great powers.

This new international situation opened the door for the

unification of Italy and Germany.

National Unification and the

National State, 1848--1871

Q

Focus Question: W hat actions did Cavour and Bismarck

take to bring about unification in Italy and Germany,

respectively, and what role did war play in their efforts?

The revolutions of 1848 had failed, but within twenty-five

years, many of the goals sought by liberals and nation-

alists during the first half of the nineteenth century were

achieved. Italy and Germany became nations, and many

European states were led by constitutional monarchs.

The Unification of Italy

The Italians were the first people to benefit from the

breakdown of the Concert of Europe. In 1850, A ustria was

In these conversations, excited as they were, certain ideas and catch-

words worked themselves to the surface, which expressed more or

less the feelings of the people. Now had arrived in Germany the day

for the establishment of ‘‘German Unity,’’ and the founding of a

great, powerful national German Empire. In the first line the convo-

cation of a national parliament. Then the demands for civil rights

and liberties, free speech, free press, the right of free assembly, equal-

ity before the law, a freely elected representation of the people with

legislative power, responsibility of ministers, self-government of the

communes, the right of the people to carr y arms, the formation of a

civic guard with elective officers, and so on---in short, that which was

called a ‘‘constitutional form of government on a broad democratic

basis.’’ Republican ideas were at first only sparingly expressed. But

the word democracy was soon on all tongues, and many, too, thought

it a matter of course that if the princes should try to withhold from

the people the rights and liberties demanded, force would take the

place of mere petition. Of course the regeneration of the fatherland

must, if possible, be accomplished by peaceable means. ... Like

many of my friends, I was dominated by the feeling that at last the

great opportunity had arrived for giving to the German people the

liberty which was their birthright and to the German fatherland its

unity and greatness, and that it was now the first duty of every

German to do and to sacrifice everything for this sacred object.

Q

What arguments did Macaulay use to support the Reform

Bill of 1832? Was he correct? Why or why not? Why was Carl

Schurz so excited when he heard the news about the revolution

in France? Do you think being a university student helps explain

his reaction? Why or why not? What differences do you see in

the approaches of these two writers? What do these selections

tell you about the development of politics in the German states

and Britain in the nineteenth century?

(continued)

NATIONAL UNIFICATION AND THE NATIONAL STATE, 1848--1871 479

still the dominant power on the Italian peninsula. After

the failure of the revolution of 1848--1849, more and more

Italians looked to the northern Italian state of Piedmont,

ruled by the royal house of Savoy, as their best hope to

achieve the unification of Italy. It was, however , doubtful

that the little state could provide the leadership needed to

unify Italy until King Victor Emmanuel II (1849--1878;

1861--1878 as king of Italy) named Count Camillo di

Cavour (1810--1861) prime minister in 1852.

As prime minister, Cavour pursued a policy of eco-

nomic expansion that increased government revenues and

enabled Piedmont to equip a large army. Cavour, allied

with the French emperor,

Louis Napoleon, defeated the

Austrians and gained control

of Lombardy. Cavour’s success

caused nationalists in some

northern Italian states (Parma,

Modena, and Tuscany) to

overthrow their governments

and join Piedmont.

Meanwhile, in southern

Italy, Giuseppe Garibaldi

(1807--1882), a dedicated Ital-

ian patriot, raised an army of a

thousand volunteers called Red

Shirts because of the color of

their uniforms. Garibaldi’s

forces swept through Sicily and

then crossed over to the

mainland and began a victori-

ous march up the Italian pen-

insula. Naples, and with it the

Kingdom of the Two Sicilies,

fell in early September in 1860.

Ever the patriot, Garibaldi

chose to turn over his con-

quests to Cavour’s Piedmon-

tese forces. On March 17, 1861,

the new kingdom of Italy was

proclaimed under a centralized

government subordinated to

the control of Piedmont and

King Victor Emmanuel II of

the house of Savoy. The task of

unification was not yet com-

plete, however. Venetia in the

north was taken from Austria

in 1866. The Italian army an-

nexed the city of Rome on

September 20, 1870, and it

became the new capital of the

united Italian state.

The Unification

of Ger many

After the failure of the Frank-

furt Assembly to achieve Ger-

man unification in 1848--1849,

more and more Germans

looked to Prussia for leader-

ship in the cause of German

unification. Prussia had be-

come a strong, prosperous, and

authoritarian state, with the

Prussian king in firm control

of both the government and

the army. In 1862, King

W illiam I (1861--1888) ap-

pointed a new prime minister,

Count Otto von Bismarck

(1815--1898). Bismar ck has

often been portrayed as the

ultimate realist, the foremost

nineteenth-century practitioner

of Realpolitik---the ‘‘ politics of

reality.’’ He said, ‘‘Not by

speeches and majorities will the

great questions of the day be

decided---that was the mistak e

of 1848--1849---but by iron and

blood.’’

5

Opposition to his do-

mestic policy determined Bis-

marck on an active foreign

policy, which led to war and

German unification.

After defeating Denmark

with Austrian help in 1864 and

gaining control ov er the duch-

ies of Schleswig and Holstein,

Bismarck created friction with

the A ustrians and goaded them

into a war on J une 14, 1866.

Mediterranean

Sea

Adriatic Sea

P

o

R

.

M

A

R

C

H

E

S

U

M

B

R

I

A

Corsica

Sardinia

Sicily

SWITZERLAND

FRANCE

AUSTRIAN

EMPIRE

OTTOMAN

EMPIRE

KINGDOM

OF THE

TWO SICILIES

PAPAL

TUSCANY

MODENA

PIEDMONT

SAVOY

LOMBARDY

VENETIA

PARMA

ROMAGNA

STATES

Rome

Messina

Florence

Naples

Genoa

Magenta

Milan

Venice

Solferino

Nice

Turin

KINGDOM OF

PIEDMONT

0 100 200 Miles

0 100 200 300 Kilometers

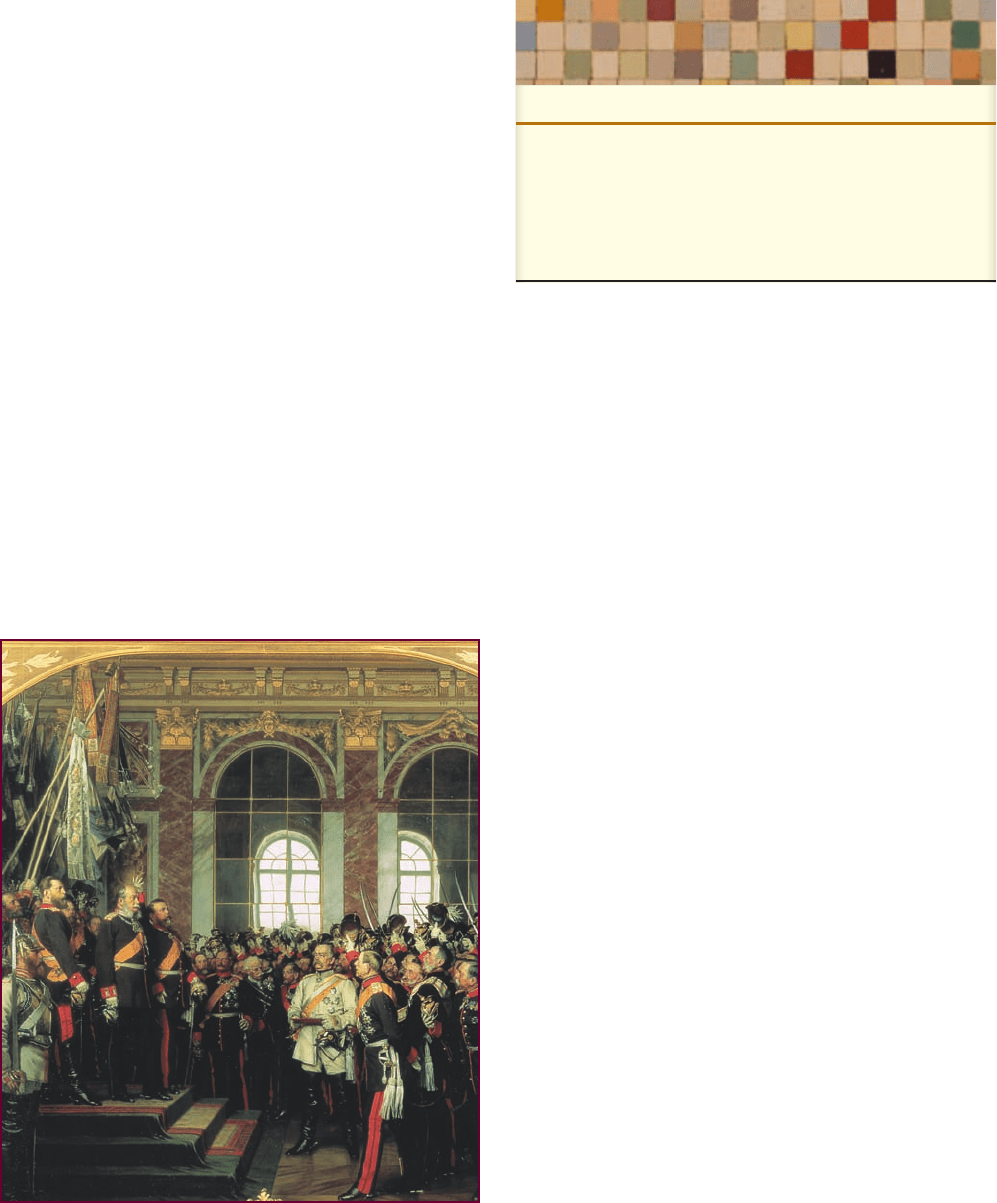

Kingdom of Piedmont, before 1859

To Kingdom of Piedmont, 1859

To Kingdom of Piedmont, 1860

To Kingdom of Italy, 1866, 1870

The Un ification of Italy

CHRONOLOGY

The Unification of Italy

Victor Emmanuel II 1849--1878

Count Cavour becomes prime minister

of Piedmont

1852

Garibaldi’s invasion of the Two Sicilies 1860

Kingdom of Italy is proclaimed March 17, 1861

Italy’s annexation of Venetia 1866

Italy’s annexation of Rome 1870

B

a

l

t

i

c

S

e

a

W

e

s

e

r

R

.

R

h

i

n

e

E

l

b

e

R

.

O

d

e

r

R

.

D

a

n

u

b

e

R

.

M

a

i

n

R.

R.

WÜRTTEMBERG

DENMARK

SWEDEN

NETHERLANDS

BELGIUM

FRANCE

SWITZERLAND

AUSTRIAN

EMPIRE

PRUSSIA

LUXEMBOURG

Hamburg

Amsterdam

Brussels

Sedan

Verdun

Strasbourg

Munich

Trier

Frankfurt

Cologne

Weimar

Leipzig

Dresden

Berlin

Vienna

Prague

Nuremberg

Mainz

ALSACE

LORRAINE

BADEN

HESSE-

CASSEL

WEST

PRUSSIA

SCHLESWIG

HOLSTEIN

OLDENBURG

HANOVER

MECKLENBURG

BAVARIA

HESSE-

DARMSTADT

0 50 100 Miles

0 100 200 Kilometers

Prussia, 1862

United in 1866–1867

with Prussia as North

German Confederation

South German

Confederation

Annexed in 1871 after

Franco-Prussian War

The Unificati on o f G ermany

480 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

Though the Austrians were barely defeated at K

€

oniggr

€

atz

on July 3, Prussia proceeded to organize the German

states north of the Main River into the North German

Confederation. The southern German states, largely

Catholic, remained independent but signed military

alliances with Prussia due to their fear of France, their

western neighbor.

Prussia now dominated all of northern Germany, but

problems with France soon arose. Bismarck realized that

France would never be content with a strong German

state to its east because of the potential threat to French

security. Bismarck goaded the French into declaring war

on Prussia on July 15, 1870. The Prussian armies ad-

vanced into France, and at Sedan, on September 2, 1870,

they captured an entire French army and the French

emperor Napoleon III himself. Paris capitulated on

January 28, 1871. France had to give up the provinces of

Alsace and Lorraine to the new German state, a loss that

left the French burning for revenge.

Even before the war had ended, the southern

German states had agreed to enter the North German

Confederation. On January 18, 1871, in the Hall of

Mirrors in Louis XIV’s palace at Versailles, William I was

proclaimed kaiser (emperor) of th e Second Germa n

Empire (the first was the medieval Holy Roman Em-

pire). German unity had been achieved by the Prussian

monarchy and the Prussian army. The Prussian lead er-

ship of German unification meant the triumph of au-

thori tarian, militaristic values over liberal, constitutional

sentiments in th e development of the new German state.

With its industrial resources and military might, the new

state had become the strongest power on t he Continent.

A new European balance of power was at hand.

Nationalism and Reform: The European

National State at Mid-Century

Unlike nations on the Continent, Great Britain managed

to avoid the revolutionary upheavals of the first half of

the nineteenth century. In the early part of the century,

Great Britain was governed by the aristocratic landown-

ing classes that dominated both houses of Parliament. But

in 1832, to avoid turmoil like that on the Continent,

Parliament passed a reform bill that increased the number

of male voters, chiefly by adding members of the indus-

trial middle class. By allowing the industrial middle class

to join the landed interests in ruling Britain, Britain

avoided revolution in 1848.

In the 1850s and 1860s, the British liberal parlia-

mentary system made both social and political reforms

that enabled the country to remain stable. One of the

other reasons for Britain’s stability was its continuing

economic growth. After 1850, middle-class prosperity was

at last coupled with some improvements for the working

classes as real wages for laborers increased more than

25 percent between 1850 and 1870. The British sense of

national pride was well reflected in Queen Victoria

(1837--1901), whose sense of duty and moral respect-

ability reflected the attitudes of her age, which has ever

since been known as the Victorian Age.

Events in France after the revolution of 1848 moved

toward the restoration of monarchy. Four years after his

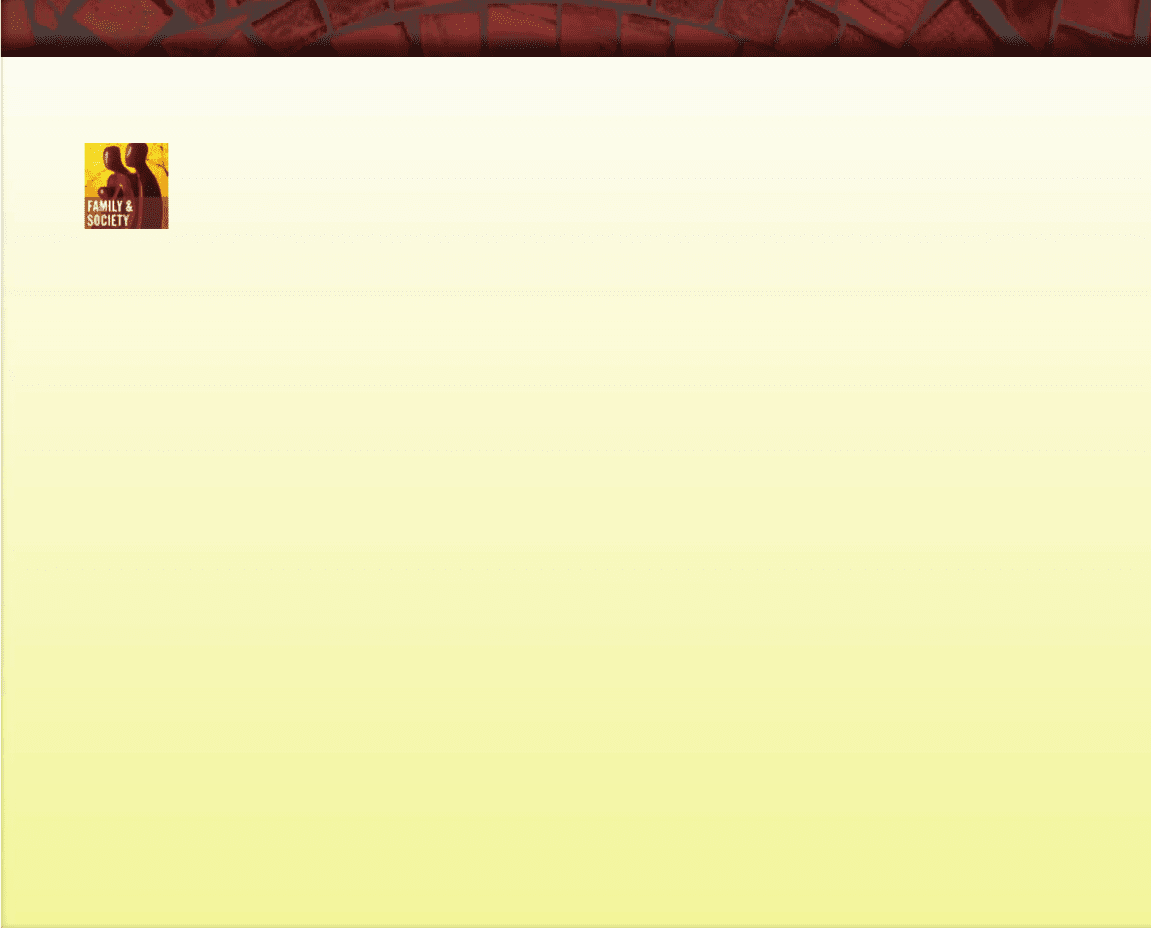

The Unification of Germa ny. Under Prussian leadership, a new

German empire was proclaimed on January 18, 1871, in the Hall of

Mirrors in the palace of Versailles. King William of Prussia became

Emperor William I of the Second German Empire. Otto von Bismarck, the

man who had been so instrumental in creating the new German state, is

shown here, resplendently attired in his white uniform, standing at the foot

of the throne.

CHRONOL OGY

The Unification of Germany

King William I of Prussia 1861--1888

Danish War 1864

Austro-Prussian War 1866

Franco-Prussian War 1870--1871

German Empire is proclaimed January 18, 1871

c

Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbestiz/Art Resource, NY

NATIONAL UNIFICATION AND THE NATIONAL STATE, 1848--1871 481

election as president, Louis Napoleon restored an au-

thoritarian empire. On December 2, 1852, Louis Napo-

leon assumed the title of Napoleon III (the first Napoleon

had abdicated in favor of his son, Napoleon II, on April 6,

1814). The Second Empire had begun.

The first f ive years of Napoleon III’s reign were a

spectacular success. He took many steps to expand in-

dustrial growth. Governm ent subsidies helped foster the

rapid construction of railroads as well as harbors, roads,

and canals. The majo r French railway lines were com-

pleted during Napoleon III’s reign, and iron production

tripled. In the midst of this economic expansion,

Napoleon III also underto ok a vast reconstruction of the

city of Paris. The medieval Paris of narrow streets and

old city walls was destroyed a nd replaced by a modern

Paris of broad boulevards, sp acious buildings, an un-

derground sewage system, a new public water supply,

and gaslights.

In the 1860s, as opposition to his rule began to

mount, Napoleon III began to liberalize his regime. He

gave the Legislative Corps more say in affairs of state,

including debate over the budget. Liberalization policies

worked initially; in a plebiscite in May 1870 on whether

to accept a new constitution that might have inaugurated

a parliamentary regime, the French people gave Napoleon

III a resounding victory. This triumph was short-lived,

however. War with Prussia in 1870 brought Napoleon

III’s ouster, and a republic was proclaimed.

Although nationalism was a major force in

nineteenth-century Europe, one of the region’s most

powerful states, the Austrian Empire, managed to

frustrate the desire of its numerous ethnic groups for

self-determination. After the Habsburgs had crushed

the revolutions of 1848--1849, they restored centralized,

autocratic government to the empire. But Austria’s

defeat at the hands of the Prussians in 1866 forced

the Austrians to deal with the fiercely nationalistic

Hungarians.

The result was the negotiated Ausgleich,orCom-

promise, of 1867, which created the dual monarchy of

A ustria-H ungary. Each part of the empire now had its own

constitution, its own legislature, its own governmental

bureaucracy, and its own capital (Vienna for Austria and

Budapest for Hungary). Holding the two states together

were a single monarch---Francis Joseph (1848--1916) was

emperor of Austria and king of Hungary---and a common

army, foreign policy, and system of finances.

At the beginning of the nineteenth centur y, Russia

was overwhelmingly rural, agricultural, and autocratic.

The Russian imperial autocracy, based on soldiers, se-

cret police, and repression, had w ithstood the revolu-

tionary fervor of the first half of the nineteenth centur y.

Defeat in the Crimean War in 1856, however, led even

staunch conservatives to realize that Russia was falling

hopelessly behind the western European powers. Tsar

Alexander II (1855--1881) decided to make serious

reforms.

Serfdom was the most burdensome problem in tsarist

Russia. On March 3, 1861, Alexander issued his eman-

cipation edict (see the box on p. 483). Peasants were now

free to own property and marry as they chose. But the

system of land redistribution instituted after emancipa-

tion was not that favorable to them. The government

provided land for the peasants by purchasing it from the

landlords, but the landowners often chose to keep the

best lands. The Russian peasants soon found that they

had inadequate amounts of good arable land to support

themselves.

Nor were the peasants completely free. The state

compensated the landowners for the land given to the

peasants, but the peasants were expected to repay

the state in long-term installments. To ensure that the

payments were made, peasants were subjected to the

authority of their mir or v illage commune, which was

collectively responsible for the land payments to the

government. And since the village communes were

responsible for the payments, they were relucta nt to

allow peasants to leave their land. Emancipation, then,

led not to a free, landowning peasantry along the

Western model but to an unhappy, land-starved peas-

antry that largely followed the old ways of agricultural

production.

The European State, 1871--1914

Q

Focus Questions: What general political trends were

evident in the nations of western Europe in the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and to what

degree were those trends also apparent in the nations

of central and eastern Europe? How did the growth of

nationalism affect international affairs during the same

period?

Throughout much of Europe by 1870, the national state

had become the focus of people’s loyalties. Only in Russia,

eastern Europe, Austria-Hungary, and Ireland did na-

tional groups still struggle for independence.

Within the major European states, considerable

progress was made in achieving such liberal practices as

constitutions and parliaments, but it was largely in the

western European states that mass politics became a re-

ality. Reforms encouraged the expansion of political de-

mocracy through voting rights for men and the creation

482 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

of mass political parties. At the same time, however,

similar reforms were strongly resisted in parts of Europe

where the old political forces remained strong.

Western Europe: The Growth

of Political Democracy

By 1871, Great Britain had a functioning two-party par-

liamentary system. For the next fifty years, Liberals and

Conservatives alternated in power at regular intervals.

Both parties were dominated by a ruling class composed

of aristocratic landowners and upper-middle-class busi-

nesspeople. And both competed with each other in

passing laws that expanded the right to vote. By 1918, all

males over twenty-one and women over thirty could vote.

Political democracy was soon accompanied by social

welfare measures for the working class.

The growth of trade unions, which advocated more

radical change of the economic system, and the emer-

gence in 1900 of the Labour Party, which dedicated itself

to the interests of the workers, caused the Liberals, who

held the government from 1906 to 1914, to realize that

they would have to create a program of social welfare or

lose the support of the workers. Therefore, they voted for

a series of social reforms. The National Insurance Act of

1911 provided benefits for workers in case of sickness and

unemployment. Additional legislation provided a small

pension for those over seventy.

EMANCIPATION:SERFS AND SLAVES

Although overall their histories have been quite

different, Russia and the United States shared a

common feature in the 1860s. They were the only

states in the Western world that still had large

enslaved populations (the Russian serfs were virtually slaves).

The leaders of both countries issued emancipation proclama-

tions within two years of each other. The first excerpt is taken

from the imperial decree of March 3, 1861, which freed the

Russian serfs. The second excerpt is from Abraham Lincoln’s

Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863.

Alexander II’s Imperial Decree, March 3, 1861

By the grace of God, we, Alexander II, Emperor and Autocrat of all

the Russias, King of Poland, Grand Duke of Finland, etc., to all our

faithful subjects, make known:

Called by Divine Providence and by the sacred right of inheri-

tance to the throne of our ancestors, we took a vow in our inner-

most heart to respond to the mission which is intrusted to us as to

surround with our affection and our Imperial solicitude all our

faithful subjects of every rank and of every condition, from the war-

rior, who nobly bears arms for the defense of the country, to the

humble artisan devoted to the works of industry; from the official

in the career of the high offices of the State to the laborer whose

plough furrows the soil. ...

We thus came to the conviction that the work of a serious

improvement of the condition of the peasants was a sacred

inheritance b equeathe d to us by o ur ancestors, a mission which,

in the course of events, Divine Prov idence called upon us to

fulfill. ...

In virtue of the new dispositions above mentioned, the peasants

attached to the soil will be invested within a term fixed by the law

with all the rights of free cultivators. ...

At the same time, they are granted the right of purchasing their

close, and, with the consent of the proprietors, they may acquire in

full property the arable lands and other appurtenances which are

allotted to them as a permanent holding. By the acquisition in full

property of the quantity of land fixed, the peasants are free from

their obligations toward the proprietors for land thus purchased, and

they enter definitely into the condition of free peasant-landholders.

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation,

Januar y 1, 1863

Now therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States,

by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief of the

Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebel-

lion against the authority and government of the United States, and

as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing such rebellion,

do, on this 1st day of January,

A.D. 1863, and in accordance with my

purpose to do so, ...order and designate as the States and parts of

States wherein the people thereof, respectively, are this day in rebel-

lion against the United States the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, ...Mississippi, Alabama, Florida,

Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia. ...

And by virtue of the power for the purpose aforesaid, I do

order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said desig-

nated States and parts of States are, and henceforward shall be free;

and that the Executive Government of the United States, including

the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and main-

tain the freedom of said persons.

Q

What changes did Tsar Alexander II’s emancipation of the

serfs initiate in Russia? What effect did Lincoln’s Emancipation

Proclamation have on the southern ‘‘armed rebellion’’? What

reasons did each leader give for his action?

THE EUROPEAN STATE, 1871--1914 483

In France, the confusion that ensued after the col-

lapse of Louis Napoleon’s Second Empire finally ended in

1875 when an improvised constitution established a re-

publican form of government---the Third Republic---that

lasted sixty-five years. France’s parliamentary system was

weak, however, because the existence of a dozen political

parties forced the premier (or prime minister) to depend

on a coalition of parties to stay in power. The Third

Republic was notorious for its changes of government.

Nevertheless, by 1914, the French Third Republic com-

manded the loyalty of most French people.

Central and Eastern Europe:

Persistence of the Old Order

The constitution of the new imperial Germany begun by

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1871 provided for a

bicameral legislature. The lower house of the German

parliament, the Reichstag, was elected by universal male

suffrage, but it did not have ministerial responsibility.

Ministers of government, among whom the most im-

portant was the chancellor, were responsible to the em-

peror, not the parliament. The emperor also commanded

the armed forces and controlled foreign policy and the

government.

During the reign of Emperor William II (1888--

1918), the new imperial Germany begun by Bismarck

continued as an ‘‘authoritarian, conservative, military-

bureaucratic power state.’’ By the end of William’s reign,

Germany had become the strongest military and indus-

trial power on the Continent, but the rapid change had

also helped produce a society torn between moderniza-

tion and traditionalism. With the expansion of industry

and cities came demands for true democracy. Conserva-

tive forces, especially the landowning nobility and in-

dustrialists, two of the powerful ruling groups in imperial

Germany, tried to block the movement for democracy by

supporting William II’s activist foreign policy. Expansion

abroad, they believed, would divert people’s attention

from the yearning for democracy at home.

After the creation of the dual monarchy of Austria-

Hungary in 1867, the Austrian part received a constitu-

tion that theoretically established a parliamentary system.

In practice, however, Emperor Francis Joseph (1848--

1916) largely ignored parliament, ruling by decree when

parliament was not in session. The problem of the various

nationalities also remained troublesome. The German

minority that governed Austria felt increasingly threat-

ened by the Czechs, Poles, and other Slavic groups within

the empire. Their agitation in the parliament for auton-

omy led prime ministers after 1900 to ignore the parlia-

ment and rely increasingly on imperial decrees to govern.

In Russia, the assassination of Alexander II in 1881

convinced his son and successor, Alexander III (1881--

1894), that reform had been a mistake, and he lost no

time in persecuting both reformers and revolutionaries.

When Alexander III died, his weak son and successor,

Nicholas II (1894--1917), began his rule with his father’s

conviction that the absolute power of the tsars should be

preserved: ‘‘I shall maintain the principle of autocracy just

as firmly and unflinchingly as did my unforgettable

father.’’

6

But conditions were changing.

Industrialization progressed rapidly in Russia after

1890, and with industrialization came factories, an in-

dustrial working class, and the development of socialist

parties, including the Marxist Social Democratic Party

and the Social Revolutionaries. Although repression

forced both parties to go underground, the growing op-

position to the tsarist regime finally exploded into revo-

lution in 1905.

The defeat of the Russians by the Japanese in 1904--

1905 encouraged antigovernment groups to rebel against

the tsarist regime. Nicholas II granted civil liberties and

created a legislative assembly, the Duma, elected directly

by a broad franchise. But real constitutional monarchy

proved short-lived. By 1907, the tsar had curtailed the

power of the Duma and relied again on the army and

bureaucracy to rule Russia.

International Rivalries and the Winds of War

Bismarck had realized in 1871 that the emergence of a

unified Germany as the most powerful state on the

CHRONOLOGY

The National State, 1870--1914

Great Britain

Formation of Labour Party 1900

National Insurance Act 1911

France

Republican constitution (Third Republic) 1875

Germany

Bismarck as chancellor 1871--1890

Emperor William II 1888--1918

Austria-Hungary

Emperor Francis Joseph 1848--1916

Russia

Tsar Alexander III 1881--1894

Tsar Nicholas II 1894--1917

Russo-Japanese War 1904--1905

Revolution 1905

484 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

Continent (see Map 19.3) had upset the balance of power

established at Vienna in 1815. Fearful of a possible anti-

German alliance between France and Russia, and possibly

even Austria, Bismarck made a defensive alliance with

Austria in 1879. Three years later, this German-Austrian

alliance was enlarged with the entrance of Italy, angry

with the French over conflicting colonial ambitions in

North Africa. The Triple Alliance of 1882---Germany,

Austria-Hungary, and Italy---committed the three powers

to a defensive alliance against France. At the same time,

Bismarck maintained a separate treaty with Russia.

When Emperor William II cashiered Bismarck in

1890 and took over direction of Germany’s foreign policy,

he embarked on an activist foreign policy dedicated to

enhancing German power by finding, as he put it, Ger-

many’s rightful ‘‘place in the sun.’’ One of his changes in

Bismarck’s foreign policy was to drop the treaty with

Russia, which he viewed as being at odds with Germany’s

Cyprus

Crete

Sicily

Sardinia

Corsica

Black Sea

Atlantic

Ocean

Arctic Ocean

FINLAND

GREECE

MOROCCO

ALGERIA

TUNISIA

ITALY

SPAIN

PORTUGAL

FRANCE

GREAT

BRITAIN

BELGIUM

NETHERLANDS

LUXEMBOURG

SWITZERLAND

AUSTRIA

HUNGARY

ROMANIA

SERBIA

BULGARIA

BOSNIA

HERZ.

MONTENEGRO

ALBANIA

M

A

C

E

D

O

N

I

A

CROATIA -

SLOVENIA

B

E

S

S

A

R

A

B

I

A

CRIMEA

RUSSIAN

EMPIRE

OTTOMAN EMPIRE

Athens

Naples

Rome

Venice

Tunis

Algiers

Tangier

Lisbon

Madrid

Marseilles

Paris

Munich

London

Saint Petersburg

Moscow

Kiev

Odessa

Sinope

Constantinople

Budapest

Sevastopol

R

h

i

n

e

R

.

V

o

l

g

a

R

.

P

o

R

.

E

b

r

o

R

.

A

l

p

s

T

a

u

r

u

s

M

t

s

.

B

a

l

e

a

r

i

c

I

s

l

a

n

d

s

P

y

r

e

n

e

e

s

Mediterranean Sea

North

Sea

Baltic

Sea

POLAND

DENMARK

NORWAY

and

SWEDEN

AUSTRIA-

HUNGARY

Kristiania

Stockholm

Helsingfors

Prague

Warsaw

Dresden

Berlin

Copenhagen

E

l

b

e

R

.

Vienna

O

d

e

r

R

.

D

a

n

u

b

e

R

.

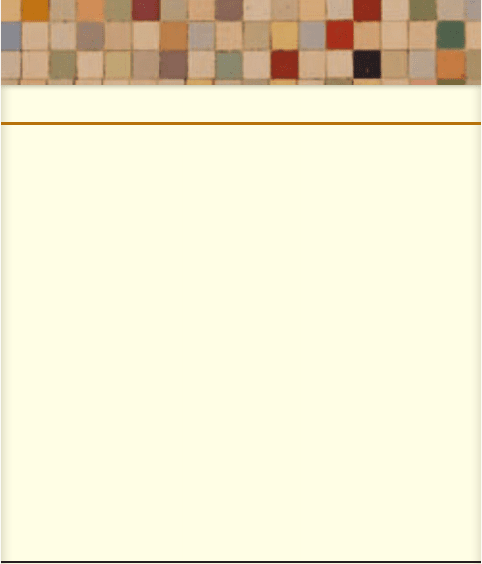

German Empire

Austria-Hungary

Italy

France

Ottoman Empire

0 250 500 Miles

0 250 500 750 Kilometers

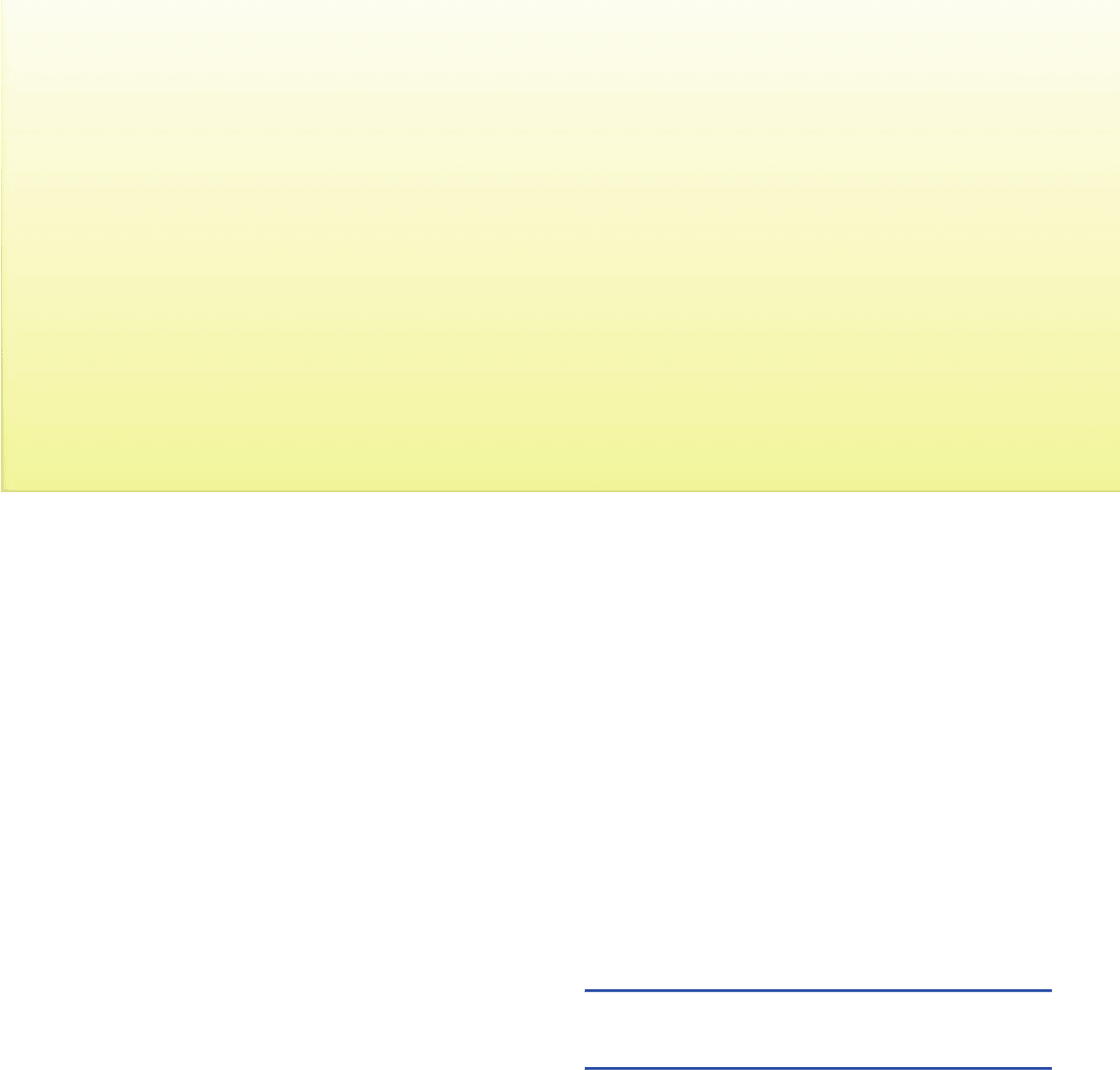

MAP 19.3 Europe in 1871. German unification in 1871 upset the balance of power

established at Vienna in 1815 and eventually led to a realignment of European alliances.

By 1907, Europe was divided into two opposing camps: the Triple Entente of Great Britain,

Russia, and France and the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy.

Q

How was German y affected by the formation of the Triple Entente?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www .cengage.com/ history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

THE EUROPEAN STATE, 1871--1914 485