Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Revolution. A better quality of iron came into

being in the 1780s when Henry Cort devel-

ope d a system called puddling, in which coke,

derived from coal, was used t o burn away

imp urities in pig iron (crude iron) and pro-

duce an iron of high quality. A boom then

ensued in the British iron industry. By 1852,

Bri tain produced almost 3 million tons of iron

annually, more than the rest of the world

combined.

The new high-quality wrought iron was in

turn used to build new machines and ultimately

new industries. In 1804, Richard Trevithick

pioneered the first steam-powered locomotive

on an industrial rail line in southern Wales. It

pulled 10 tons of ore and seventy people at

5 miles per hour. Better locomotives soon fol-

lowed. Engines built by George Stephenson and

his son proved superior, and it was Stephenson’s

Rocket that was used on the first public railway

line, which opened in 1830, extending 32 miles

from Liverpool to Manchester. Rocket sped

along at 16 miles per hour. Within twenty years,

locomotives were traveling at 50 miles per hour.

By 1840, Britain had almost 6,000 miles of

railroads.

The railroad was an important contributor

to the success and maturing of the Industrial

Revolution. Railway construction created new

job opportunities, especially for farm laborers

and peasants who had long been accustomed to

finding work outside their local villages. Per-

haps most important, the proliferation of a

cheaper and faster means of transportation had

a ripple effect on the growth of the industrial

economy. As the prices of goods fell, markets

grew larger; increased sales meant more facto-

ries and more machinery, thereby reinforcing

the self-sustaining aspect of the Industrial

Revolution, a fundamental break with the tra-

ditional European economy. Continuous, self-

sustaining economic growth came to be ac-

cepted as a fundamental characteristic of the

new economy.

The Industrial Factory Another visible sym-

bol of the Industrial Revolution was the factory

(see the comparative illustration at the right).

From its beginning, the factory created a new

labor system. Factory owners wanted to use their new

machines constantly. Workers were therefore obliged to

work regular hours and in shifts to keep the machines

producing at a steady rate. Early factory workers,

however, came from rural areas, where they were used to

a different pace of life. Peasant farmers worked hard,

especially at harvest time, but they were also used to

periods of inactivity.

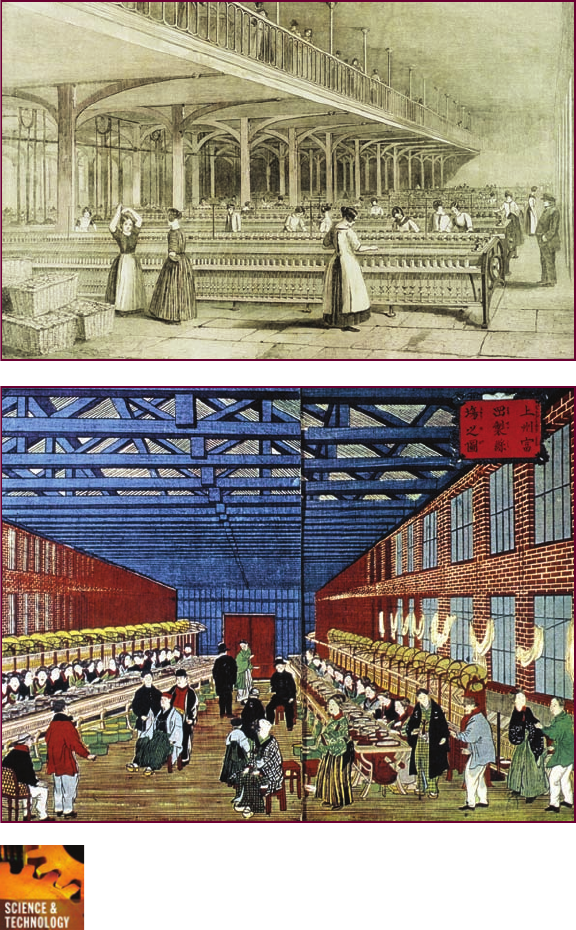

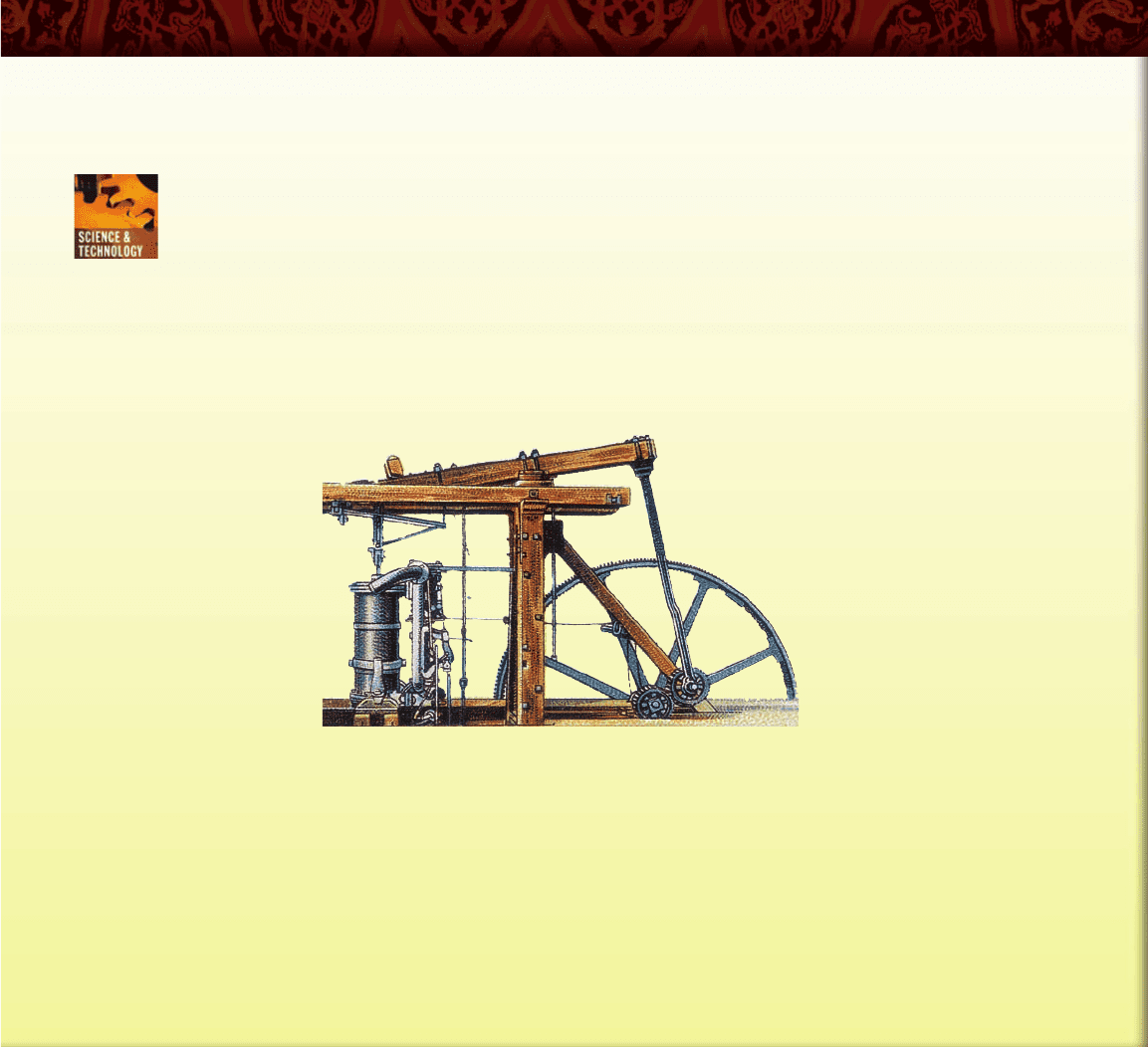

COMPARATIVE ILLUSTRATION

Textile F actories, West and East. The development of

the factory changed the relationship betwe en workers and

employers as workers had to adjust to a new system of

discipline that required them to work regular hours under close supervision.

At the top is an 1851 illustration that shows women working in a British

cotton factory. The factory system came later to the rest of the world than it

did in Britain. Shown at the bottom is one of the earliest industrial factories

in Japan, the Tomioka silk factory, built in the 1870s. Note that although

women are doing the work in both factories, the managers are men.

Q

What do you think were the major differences and similarities between

British and Japanese factories (see also the box on p. 470)?

c

CORBIS

c

The Art Archive/Laurie Platt Winfrey

466 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

Early factory owners therefore had to institute a

system of work discipline that required employees to

became accustomed to working regular hours and doing

the same work over and over. Of course, such work was

boring, and factory owners resorted to tough methods to

accomplish their goals. They issued minute and detailed

factory regulations. Adult workers were fined for a wide

variety of minor infractions, such as being a few minutes

late for work, and dismissed for more serious misdoings,

especially drunkenness, which set a bad example for

younger workers and also courted disaster in the midst of

dangerous machinery. Employers found that dismissals

and fines worked well for adult employees; in a time when

great population growth had produced large masses of

unskilled labor, dismissal meant disaster. Children were

less likely to understand the implications of dismissal, so

they were sometimes disciplined more directly---often by

beating. As the nineteenth century progressed, the second

and third generations of workers came to view a regular

workweek as a natural way of life.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Great Britain had

become the world’s first and richest industrial nation.

Britain was the ‘‘workshop, banker, and trader of the

world.’’ It produced one-half of the world’s coal and

manufactured goods; in 1850, its cotton industry alone

was equal in size to the industries of all other European

countries combined.

The Spread of Industrialization

From Great Britain, industrialization spread to the con-

tinental countries of Europe and the United States at

different times and speeds during the nineteenth century.

First to be industrialized on the Continent were Belgium,

France, and the German states. Their governments were

especially active in encouraging the development of in-

dustrialization by, among other things, setting up tech-

nical schools to train engineers and mechanics and

providing funds to build roads, canals, and railroads. By

1850, a network of iron rails had spread across Europe.

The Industrial Revolution also transformed the new

nation in North America, the United States. In 1800, six

out of every seven American workers were farmers, and

there were no cities with more than 100,000 people. By

1860, however, the population had sextupled to 30 mil-

lion people (larger than Great Britain), nine U.S. cities

had populations over 100,000, and only 50 percent of

American workers were farmers.

In sharp contrast to Britain, the United States was a

large country. Thousands of miles of roads and canals

were built linking east and west. The steamboat facilitated

transportation on the Great Lakes, Atlantic coastal waters,

and rivers. Most important in the development of

an American transportation system was the railroad.

Beginning with 100 miles in 1830, by 1860 there were

more than 27,000 miles of railroad track covering the

United States. This transportation revolution turned the

United States into a single massive market for the man-

ufactured goods of the Northeast, the early center of

American industrialization.

Limiting the Spread of Industrialization

to the Rest of the World

Before 1870, the industrialization that was transforming

western and central Europe and the United States did not

extend in any significant way to the rest of the world

(see the comparative essay ‘‘The Industrial Revolution’’ on

p. 468). Even in eastern Europe, industrialization lagged

far behind. Russia, for example, was still largely rural and

agricultural, ruled by an autocratic regime that preferred

to keep the peasants in serfdom.

In other parts of the world where they had established

control (see Chapter 21), newly industrialized European

states pursued a deliberate policy of preventing the growth

of mechanized industry. The experience of India is a good

example. In the eighteenth century, India had become one

of the world’s greatest exporters of cotton cloth produced

by hand labor. In the first half of the nineteenth century,

much of India fell under the control of the British East

India Company. With British control came inexpensive

British factory-produced textiles, and soon thousands of

Indian spinners and handloom weavers were unemployed.

British policy encouraged Indians to export their raw

materials while buying British-made goods.

The Social Impact of the Industrial Revolution

Ev entually, the Industrial R evolution revolutionized the

social life of Eur ope and the world. This change was already

evident in the first half of the nineteenth century in the

growth of cities and the emergence of new social classes.

Population Growth and Urbanization Population in-

creases had already begun in the eighteenth century, but

they became dramatic in the nineteenth century. In 1750,

the total European population stood at an estimated

140 million; by 1850, it had almost doubled to 266 mil-

lion. The key to the expansion of population was the

decline in death rates throughout Europe. Wars and

major epidemic diseases, such as plague and smallpox,

became less frequent, which led to a drop in the number

of deaths. Thanks to the increase in the food supply, more

people were better fed and more resistant to disease.

Throughout Europe, cities and towns grew dra-

matically in the first half of the nineteenth century, a

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION AND ITS IMPACT 467

phenomenon related to industrialization. By 1850,

especially in Great Britain and Belgium, cities were rap-

idly becoming home to many industries. With the steam

engine, factory owners could locate their manufacturing

plants in urban centers where they had ready access to

transportation facilities and large numbers of new ar-

rivals from the country looking for work.

In 1800, Great Britain had one major city, London,

with a population of one million, and six cities with

populations between 50,000 and 100,000. Fifty years later,

London’s population had swelled to 2,363,000, and there

were nine cities with populations over 100,000 and

eighteen cities with populations between 50,000 and

100,000. More than 50 percent of the British population

lived in towns and cities by 1850. Urban populations also

grew on the Continent, but less dramatically.

The dramatic growth of cities in the first half of the

nineteenth century produced miserable living conditions

for many of the inhabitants. Located in the center of most

industrial towns were the row houses of the industrial

workers. Rooms were not large and were frequently

overcrowded, as a government report of 1838 in Britain

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

T

HE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Why some societies were able to embark on the

road to industrialization during the nineteenth cen-

tury and others were not has long been debated.

Some historians have found an answer in the cul-

tural characteristics of individual societies, such as the Protes-

tant work ethic in parts of Europe or the tradition of social

discipline and class hierarchy in Japan. Others have placed

more emphasis on practical reasons. To the historian Peter

Stearns, for example, the availability of capital, natural re-

sources, a network of trade relations, and navigable rivers all

helped stimulate industrial

growth in nineteenth-century

Britain. By contrast, the lack

of an urban market for agri-

cultural goods (which reduced

landowners’ incentives to in-

troduce mechanized farming)

is sometimes cited as a rea-

son for China’s failure to set

out on its own path toward

industrialization.

To some observers, the ability

of western European countries

to exploit the wealth and

resources of their co lonies in

Asia, Africa, and Latin America

was crucial to their success in achieving industrial prowess.

In their v iew, the Age o f Exploration led to the creation of a

new ‘‘world s ystem’’ characterized by the emergence o f globa l

trade networks, propelled by the rising force of European capital-

ism in pursuit of precious metals, markets, and cheap raw

materials.

These views are not mutually exclusive. In his recent book The

Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern

World Economy, Kenneth Pomeranz argued that coal resources and

access to the cheap raw materials of the Americas were both assets

for Great Britain as it became the first to enter the industrial age.

Clearly, there is no single answer to this controversy. Whatever

the case, the advent of the industrial age had a number of lasting

consequences for the world at large. On the one hand, the material

wealth of the nations that successfully passed through the process

increased significantly. In many cases, the creation of advanced in-

dustrial societies strengthened democratic institutions and led to a

higher standard of living for the majority of the population. It also

helped reduce class barriers and bring about the emancipation of

women from many of the legal

and social restrictions that had

characterized the previous era.

On the other hand, not all

the consequences of the Indus-

trial Revolution were beneficial.

In the industrializing societies

themselves, rapid economic

change often led to widening

disparities in the distribution of

wealth and a sense of rootless-

ness and alienation among

much of the population. Al-

though some societies were able

to manage these problems with

a degree of success, others expe-

rienced a breakdown of social

values and widespread political instability. In the meantime, the

transformation of Europe into a giant factory sucking up raw mate-

rials and spewing manufactured goods out to the entire world had a

wrenching impact on traditional societies whose own economic, so-

cial, and cultural foundations were forever changed by absorption

into the new world order.

Q

What were the positive and negative consequences

of the Industrial Revolution?

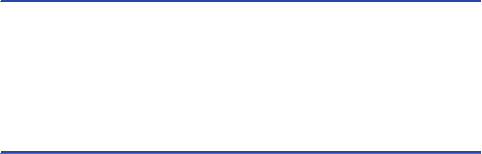

The Steam Engine. Pictured here is an early steam engine developed

by James Watt. The steam engine revolutionized the production of cotton

goods and helped usher in the factory system.

c

Oxford Science Archive/HIP/Art Resource, NY

468 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

revealed: ‘‘There were 63 families where there were at least

five persons to one bed; and there were some in which

even six were packed in one bed, lying at the top and

bottom---children and adults.’’

1

Sanitary conditions in these towns were appalling;

sewers and open drains were common on city streets: ‘‘In

the centre of this street is a gutter, into which the refuse

of animal and vegetable matters of all kinds, the dirty

water from the washing of clothes and of the houses, are

all poured, and there they stagnate and putrefy.’’

2

Unable

to deal with human excrement, cities in the early in-

dustrial era smelled horrible and were extraordinarily

unhealthy.

New Social Classes: The Industrial Middle Class The

rise of industrial capitalism produced a new middle-class

group. The bourgeoisie or middle class was not new; it

had existed since the emergence of cities in the Middle

Ages. Originally, the bourgeois was a burgher or town

dweller, active as a merchant, official, artisan, lawyer, or

man of letters. As wealthy townspeople bought land, the

original meaning of the word bourgeois became lost, and

the term came to include people involved in commerce,

industry, and banking as well as professionals such as

teachers, physicians, and government officials.

The new industrial middle class was made up of the

people who constructed the factories, purchased the

machines, and figured out where the markets were (see

the box on p. 470). Their qualities included resourceful-

ness, single-mindedness, resolution, initiative, vision,

ambition, and often, of course, greed. As Jedediah Strutt,

a cotton manufacturer said, ‘‘Getting of money ...is the

main business of the life of men.’’

Members of the industrial middle class sought to re-

duce the barriers between themselves and the landed elite,

while at the same time trying to separate themselves from

the laboring classes below them. The working class was

actually a mixture of different groups in the first half of the

nineteenth century, but in the course of the nineteenth

century, factory workers would form an industrial prole-

tariat that constituted a majority of the working class.

New Social Classes: The Industrial Working Class

Early industrial workers faced wretched working con-

ditions. Work shifts ranged from twelve to sixteen hours a

day, six days a week, with a half hour for lunch and

dinner. There was no security of employment and no

minimum wage. The worst conditions were in the cotton

mills, where temperatures were especially debilitating.

One report noted that ‘‘in the cotton-spinning work, these

creatures are kept, fourteen hours in each day, locked up,

summer and winter, in a heat of from eighty to eighty-

four degrees.’’ Mills were dirty, dusty, and unhealthy.

Conditions in the coal mines were also harsh. Al-

though steam-powered engines were used to lift coal from

the mines to the top, inside the mines, men still bore the

burden of digging the coal out while horses, mules,

women, and children hauled coal carts on rails to the lift.

Dangerous conditions, including cave-ins, explosions,

and gas fumes, were a way of life. The cramped conditions

in the mines---tunnels were often only 3 or 4 feet high---

and their constant dampness led to deformed bodies and

ruined lungs.

Both children and women worked in large numbers

in early factories and mines. Children had been an im-

portant part of the family economy in preindustrial times,

working in the fields or carding and spinning wool at

home. In the Industrial Revolution, however, child labor

was exploited more than ever. The owners of cotton

factories found child labor very helpful. Children had a

particular delicate touch as spinners of cotton. Their

smaller size made it easier for them to move under ma-

chines to gather loose cotton. Moreover, children were

more easily trained to do factory work. Above all, chil-

dren represented a cheap supply of labor. In 1821, about

half of the British population was under twenty years of

age. Hence children made up an abundant supply of la-

bor, and they were paid only about one-sixth to one-third

of what a man was paid. In the cotton factories in 1838,

children under eighteen made up 29 percent of the total

workforce; children as young as seven worked twelve to

fifteen hours per day, six days a week, in cotton mills.

By 1830, women and children made up two-thirds

of the cotton in dustry’s labor. After the Factory Act of

1833, however, the nu mber of children employed de-

clined, and th eir places were taken by women, who came

to dominate the labor forces of the early factories.

Women made up 50 pe rcent of the labor force in textile

(cotton and woolen) factories before 1870. They were

mostly unskilled laborers and were paid half or less of

what men received.

The Growth of Industrial

Prosperity

Q

Focus Questions: What was the Second Industrial

Revolution, and what effects did it have on economic

and social life? What were the main ideas of Karl

Marx, and what role did they play in politics and the

union movement in the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries?

After 1870, the Western world experienced a dynamic age

of material prosperity. The new industries, new sources

of energy, and new goods of the Second Industrial

THE GROWTH OF INDUSTRIAL PROSPERITY 469

Revolution led people to believe that their material

progress meant human progress.

New Products

The first major change in industrial development be-

tween 1870 and 1914 was the substitution of steel for

iron. New methods for shaping steel made it useful in

the construction of lighter, smaller, and faster machines

and engines, as well as railways, ships, and armaments.

In 1860, Great Britain, France, Germany, and Belgium

produced 125,000 tons of steel; by 1913, the total was

32 million tons.

Electricity was a major new form of energy that could

be easily converted into other forms of energy, such as

heat, light, and motion, and moved relatively effortlessly

through space by means of transmitting wires. In the

1870s, the first commercially practical generators of

electrical current were developed, and by 1910, hydro-

electric power stations and coal-fired steam-generating

plants enabled homes and factories in whole neighbor-

hoods to be tied into a single, common source of power.

INDUSTRIAL ATTITUDES IN BRITAIN AND JAPAN

In the nineteenth century, a new industrial middle

class in Great Britain took the lead in creating the

Industrial Revolution. Japan did not begin to indus-

trialize until after 1870 (see Chapter 22). There,

too, an industrial middle class emerged, although there were

also important differences in the attitudes of business leaders

in Britain and Japan. Some of these differences can be seen in

these documents. The first is an excerpt from Self-Help, abook

first published in 1859, by Samuel Smiles, who espoused the be-

lief that people succeed through ‘‘individual industry, energy, and

uprightness.’’ The two additional selections are by Shibuzawa

Eiichi, a Japanese industrialist who supervised textile factories.

Although his business career began in 1873, he did not write

his autobiography, the source of his first excerpt, until 1927.

Samuel Smiles, Self-Help

‘‘Heaven helps those who help themselves’’ is a well-worn maxim,

embodying in a small compass the results of vast human experience.

The spirit of self-help is the root of all genuine growth in the indi-

vidual; and, exhibited in the lives of many, it constitutes the true

source of national vigor and strength. Help from without is often

enfeebling in its effects, but help from within invariably invigorates.

Whatever is done for men or classes, to a certain extent takes away

the stimulus and necessity of doing for themselves; and where men

are subjected to overguidance and overgovernment, the inevitable

tendency is to render them comparatively helpless. ...

National progress is the sum of individual industry, energy, and

uprightness, as national decay is of individual idleness, selfishness,

and vice. ... If this view be correct, then it follows that the highest

patriotism and philanthrophy consist, not so much in altering laws

and modifying institutions as in helping and stimulating men to

elevate and improve themselves by their own free and independent

action as individuals. ...

Many popular books have been written for the purpose of com-

municating to the public the grand secret of making money. But

there is no secret whatever about it, as the proverbs of every nation

abundantly testify. ... ‘‘A penny saved is a penny gained.’’---

‘‘Diligence is the mother of good-luck.’’---‘‘No pains no gains.’’---‘‘No

sweat no sweet.’’---‘‘Sloth, the key of poverty.’’---‘‘Work, and thou

shalt have.’’---‘‘He who will not work, neither shall he eat.’’---‘‘The

world is his, who has patience and industry.’’

Shibuzawa Eiichi, Autobiography

I ... felt that it was necessary to raise the social standing of those who

engaged in commerce and industry. By way of setting an example, I

began studying and practicing the teachings of the Analects of Confu-

cius. It contains teachings first enunciated more than twenty-four hun-

dred years ago. Yet it supplies the ultimate in practical ethics for all of

us to follow in our daily living. It has many golden rules for business-

men. For example, there is a saying: ‘‘Wealth and respect are what

men desire, but unless a right way is followed, they cannot be

obtained; poverty and lowly position are what men despise, but unless

a right way is found, one cannot leave that status once reaching it.’’ It

shows very clearly how a businessman must act in this world.

Shibuzawa Eiichi on Progress

One must beware of the tendency of some to argue that it is through

individualism or egoism that the State and society can progress most

rapidly. They claim that under individualism, each individual competes

with the others, and progress results from this competition. But this is

to see merely the advantages and ignore the disadvantages, and I can-

not support such a theory . Society exists, and a State has been founded.

Although people desire to rise to positions of wealth and honor , the so-

cial order and the tranquility of the State will be disrupted if this is

done egoistically . Men should not do battle in competition with their

fellow men. Therefore, I believe that in order to get along together in

society and serve the State, we must by all means abandon this idea of

independence and self-reliance and reject egoism completely .

Q

What are the major similarities and differences between

the business attitudes of Samuel Smiles and Shibuzawa Eiichi?

How do you explain the differences?

470 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

Electricity spawned a number of inventions. The

lightbulb, developed independently by the American

Thomas Edison and the Briton Joseph Swan, permitted

homes and cities to be illuminated by electric lights. By

the 1880s, streetcars and subways powered by electricity

had appeared in major European cities. Electricity also

transformed the factory. Conveyor belts, cranes, ma-

chines, and machine tools could all be powered by elec-

tricity and located anywhere. Similarly, a revolution in

communications began when Alexander Graham Bell

invented the telephone in 1876 and Guglielmo Marconi

sent the first radio waves across the Atlantic in 1901.

The development of the internal combustion en-

gine, fired by oil an d gasoline, provided a new source of

powe r in transportation and gave rise to ocean liners as

well as to the airplane and the automobile. In 1900,

world product ion stood a t 9,000 cars, but a n Ameri can,

Henry Ford, revolutionized the automotive industry

with the mass production of the Model T. By 1916,

Ford’s factories were producing 735,000 cars a year. I n

1903, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, brothers Or v ille

and Wilbur Wrig ht made the first flight in a fixed-wing

airplane. In 1919, the first regular passenger air serv ice

was established.

New Patterns

Industrial production grew rapidly at this time because of

the greatly increased sales of manufactured goods. An

increase in real wages for workers after 1870, combined

with lower prices for manufactured goods because of

reduced transportation costs, made it easier for Euro-

peans to buy consumer products. In the cities, the first

department stores began to sell a whole new range of

consumer goods made possible by the development of the

steel and electrical industries. The desire to own sewing

machines, clocks, bicycles, electric lights, and typewriters

was rapidly generating a new consumer ethic that has

been a crucial part of the modern economy.

Not all nations benefited from the Second Industrial

Revolution. Between 1870 and 1914, Germany replaced

Great Britain as the industrial leader of Europe. Moreover,

by 1900, Europe was divided into two economic zones.

Great Britain, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Germany,

the western part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and

northern Italy constituted an advanced industrialized core

that had a high standard of living, decent systems of

transportation, and relatively healthy and educated peo-

ples (see Map 19.1). Another part of Europe, the backward

and little industrialized area to the south and east, con-

sisting of southern Italy, most of Austria-Hungary, Spain,

Portugal, the Balkan kingdoms, and Russia, was still

largely agricultural and relegated by the industrial coun-

tries to the function of providing food and raw materials.

Toward a World Economy

The economic developments of the late nineteenth cen-

tury, combined with the transportation revolution that

saw the growth of marine transport and railroads, fos-

tered a true world economy. By 1900, Europeans were

receiving beef and wool from Argentina and Australia,

coffee from Brazil, iron ore from Algeria, and sugar from

Java. European capital was also invested abroad to de-

velop railways, mines, electrical power plants, and banks.

Of course, foreign countries also provided markets for the

surplus manufactured goods of Europe. With its capital,

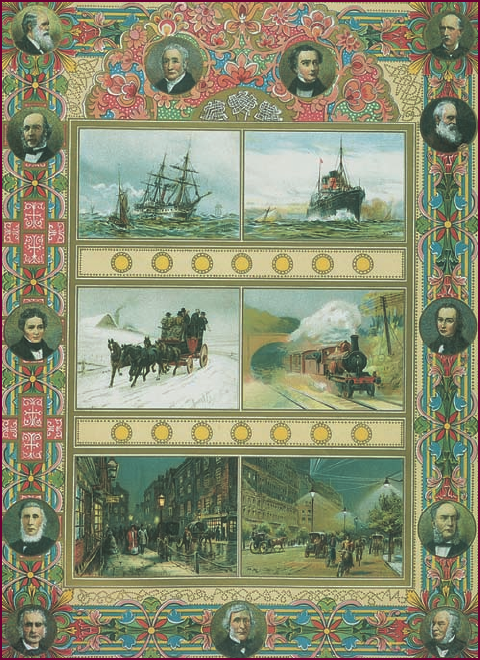

An Age of Progress. Between 1871 and 1914, the Second Industrial

Revolution led many Europeans to believe that they were living in an age

of progress when most human problems would be solved by scientific

achievements. This illustration is taken from a special issue of The

Illustrated London News celebrating the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria

in 1897. On the left are scenes from 1837, when Victoria came to the

British throne; on the right are scenes from 1897. The vivid contrast

underscored the magazine’s conclusion: ‘‘The most striking ...evidence of

progress during the reign is the ever increasing speed which the

discoveries of physical science have forced into everyday life. Steam and

electricity have conquered time and space to a greater extent during the

last sixty years than all the preceding six hundred years witnessed.’’

Photo courtesy of private collection

THE GROWTH OF INDUSTRIAL PROSPERITY 471

industries, and military might, Europe dominated the

world economy by the beginning of the twentieth century.

The Spread of Industrialization

After 1870, industrialization began to spread beyond

western and central Europe and North America. Especially

noticeable was its rapid development, fostered by gov-

ernments, in Russia and Japan. A surge of industriali-

zation began in Russia in the 1890s under the guiding

hand of Sergei Witte, the minister of finance. Witte

pushed the g overnment toward a program of ma ssive

railroad construction. By 1900, 35,000 miles of track

had been laid. Witte’s program also made possible the

D

n

i

e

p

e

e

e

r

r

e

R

R

.

A

t

l

an

t

t

i

i

c

c

O

cean

N

ort

h

S

e

a

B

B

a

a

ll

tt

ii

c

c

S

S

e

e

a

a

Bl

Bl

a

ac

k

S

e

a

E

b

b

b

b

b

r

o

R

R

R

.

S

S

e

S

i

n

e

R

.

D

D

D

D

D

a

n

u

b

e

R.

R

R

M

M

e

e

d

d

i

i

t

t

e

e

r

r

a

n

e

a

n

n

S

S

e

e

a

a

Cor

Cor

Cor

or

r

r

or

or

or

r

r

r

sic

c

c

c

c

c

c

a

a

or

or

or

r

or

or

r

c

c

c

c

c

c

Sar

Sar

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

din

ia

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

ar

ar

r

ar

a

r

a

a

aa

a

a

a

a

S

icil

y

B

B

B

a

a

l

l

l

l

e

e

e

a

a

a

r

r

i

i

i

c

c

c

I

I

I

s

s

s

I

I

I

I

l

l

l

a

a

a

l

l

n

n

d

d

d

s

s

d

d

d

R

GR

GR

GR

GR

R

R

GR

GR

R

R

R

EA

EA

E

E

EA

EA

EA

EA

EA

A

E

EA

T

T

T

GR

GR

GR

G

GR

G

G

G

GR

GR

E

E

E

E

E

R

GR

GR

R

R

R

G

EA

EA

EA

EA

EA

EA

A

GR

GR

GR

GR

GR

GR

GR

G

G

E

E

E

E

E

E

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

GG

G

G

G

G

G

G

GG

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

R

T

AI

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

N

N

N

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

BR

BR

BR

BR

I

I

IT

A

BR

A

TA

SPAIN

AI

SPA

PO

PO

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

RTUGAL

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

GA

O

R

L

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

IT

AL

Y

T

L

Y

T

A

T

FRAN

C

E

S

WITZERLAND

AN

AN

N

N

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

GERM

AN

Y

Y

Y

Y

GERM

AN

N

N

Y

Y

Y

N

Y

A

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

NE

NE

NE

E

TH

TH

TH

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

E

E

ER

ER

ER

E

ER

E

E

E

E

E

R

E

L

LA

LA

LA

LA

ND

S

ERLA

H

H

H

H

H

H

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

RL

RL

RL

R

ER

R

DS

DS

DS

BE

BE

B

LG

LG

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

IU

IU

IU

IU

IU

U

IU

I

I

IU

I

IU

U

U

U

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

IUM

LG

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

IU

IU

IU

IU

U

U

IU

U

U

IU

IU

IU

IU

U

M

M

M

M

M

IUM

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

U

M

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

A

A

USS

IA

IA

RU

U

A

A

RU

U

AU

ST

RI

A-

A

RIA

I

I

HU

NG

ARY

G

HU

Y

A

GR

GR

GR

GR

GR

GR

GR

R

GR

GR

GR

R

G

EE

EE

EE

EE

EE

EE

EE

EE

EE

EE

E

EE

E

CE

CE

CE

CE

CE

CE

CE

CE

CE

C

CE

C

CE

C

GR

GR

GR

GR

GR

GR

GR

G

EE

EE

EE

EE

EE

EE

E

C

C

CCC

C

C

C

CE

CE

CE

CE

CE

CE

E

N

ORWAY

SW

ED

EN

ED

E

M

AR

AR

AR

AR

AR

AR

AR

AR

R

R

R

A

K

K

K

AR

AR

AR

AR

AR

AR

R

A

K

K

K

A

A

A

D

DE

DE

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

D

E

N

N

NM

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

A

RR

R

R

E

E

E

E

E

E

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

R

R

R

R

R

R

K

K

AR

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

M

A

A

FINLAN

D

N

FI

N

Madrid

Mad

d

Md

d

d

d

d

B

B

B

B

B

Bar

Bar

B

B

B

ce

cel

cel

o

ona

ona

a

B

B

B

Ba

Ba

B

p

les

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

Nap

le

le

p

le

e

N

Bel

gra

de

Bel

gr

B

B

B

B

a

d

B

Mar

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

sei

sei

sei

sei

sei

sei

sei

sei

sei

se

s

l

lle

lle

e

s

s

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

sei

sei

sei

sei

sei

sei

sei

s

l

l

l

l

l

Ma

Mar

Toulouse

T

Sal

al

Sal

S

ern

rn

e

o

Lai

Lai

ai

ai

bac

bac

bac

bac

bac

h

aibac

L

c

c

c

c

c

L

L

i

moge

s

Nuremb

erg

erg

erg

g

be g

mb

erg

g

mberg

N

N

Bre

re

re

e

re

sla

s

s

u

res

B

S

aint

É

tienne

L

is

bo

n

Rom

e

R

e

Par

ar

ar

ar

i

i

is

i

i

aris

Pa

Pa

Pa

P

Par

Pa

a

a

ari

n

n

n

n

n

n

do

do

do

don

don

do

do

do

do

do

d

do

d

on

n

n

n

do

do

do

do

do

do

n

on

on

on

Lon

n

n

n

on

Lo

L

S

Sa

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

Sa

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

n

nt

n

nt

nt

n

nt

nt

n

nt

n

nt

nt

nt

t

t

nt

nt

t

nt

t

Pe

Pe

Pet

Pe

P

Pe

Pe

Pe

Pe

Pe

P

Pe

Pe

Pe

P

P

Pe

P

P

P

ersburg

S

Saint Pe

S

S

Sa

Sa

S

S

S

S

S

Sa

S

nt

nt

nt

n

nt

nt

nt

nt

Pe

Pe

P

Pe

Pe

Pe

Pe

P

Pe

Pe

P

Saint Pe

S

S

S

S

Moscow

oscow

w

w

Vie

nna

V

nn

Ber

l

l

lin

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

Be

lin

ll

Be

Sto

to

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

ckhckh

ckh

ckh

c

ckh

c

c

c

c

olm

olm

m

m

o

oo

o

o

o

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

o

o

o

o

o

o

c

c

c

c

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

S

Con

n

n

n

n

n

stasta

s

st

s

s

st

st

st

nti

i

nti

nop

nop

nop

le

le

n

n

n

n

n

n

st

s

st

st

st

st

0

0

250

50

0

500 M

ile

e

e

ss

0

0

0

2

2

2

2

50

50

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

00

00

0

750

750

750

Ki

Ki

Ki

lomlom

lom

e

et

te

e

r

rs

2

2

2

5

5

5

55

5

Steel

Engineering

Chemicals

Electrical industry

Railroad development

Lines completed by 1848

Area of main railroad

completed by1870

Other major lines

Oil production

Industrial concentration:

Cities

Areas

Low-grade coal

High-grade coal

Iron ore deposits

Petroleum deposits

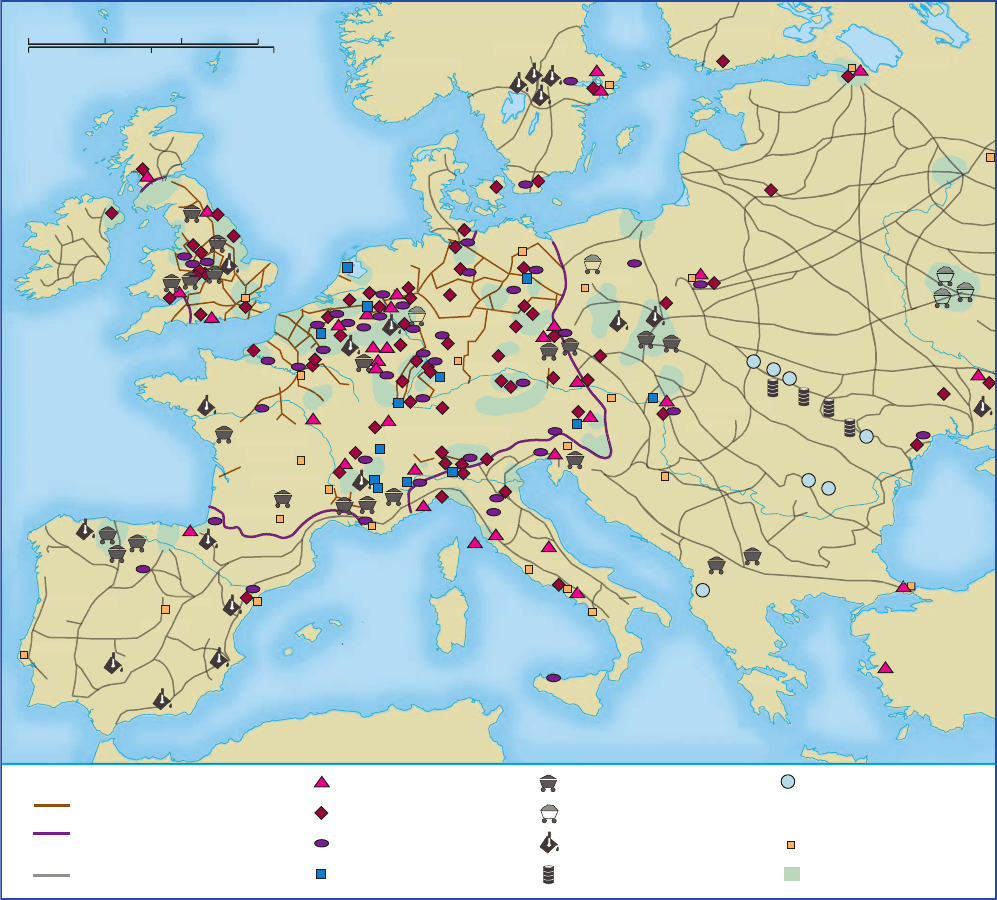

MAP 19.1 Th e I ndustrial Regions of Europ e at the End of the Ninete enth Century. By

the end of th e nineteenth century, the Second Industrial Revolution—in steelmaking, electricity,

petroleum, and chemicals—had spurred substantial economic growth and prosperity in western

and central Europe; it also sparked economic and political competition between Great Britain

and Germany.

Q

What correlation, if any, was there between industrial growth and political developments

in the nineteenth century?

472 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

rapid growth of a modern steel and coal industry,

making Russia by 1900 the fourth-largest producer of

steel, behind the United States, Germany, and Great

Britain. At the same time, Russia was also turning out

half of the world’s oil production.

In Japan, the imperial government took the lead in

promoting industry (see Chapter 22). The government

financed industries, built railroads, brought foreign ex-

perts to train Japanese employees in new industrial

techniques, and instituted a universal educational system

based on applied science. By the end of the nineteenth

century, Japan had developed key industries in tea, silk,

armaments, and shipbuilding.

Women and Work: New Job Opportunities

During the course of the nineteenth century, working-

class organizations upheld the belief that women should

remain at home to bear and nurture children and not be

allowed in the industrial workforce. Working-class men

argued that keeping women out of industrial work would

ensure the moral and physical well-being of families. In

reality, however, when their husbands were unemployed,

women had to do low-wage work at home or labor part-

time in sweatshops to support their families.

The Second Industrial Revolution opened the door to

new jobs for women. The development of larger industrial

plants and the expansion of government services created a

large number of service and white-collar jobs. The in-

creased demand for white-collar workers at relatively low

wages coupled with a shortage of male workers led em-

ployers to hire women. Big businesses and retail shops

needed clerks, typists, secretaries, file clerks, and sales-

clerks. The expansion of government services opened

opportunities for women to be secretaries and telephone

operators and to take jobs in health care and social ser-

vices. Compulsory education necessitated more teachers,

and the development of modern hospital services opened

the way for an increase in nurses.

Organizing the Working Classes

The desire to improve their working and living conditions

led many industrial workers to form socialist political

parties and socialist trade unions. These emerged after

1870, but the theory that made them possible had been

developed more than two decades earlier in the work of

Karl Marx. Marxism made its first appearance on the eve

of the revolutions of 1848 with the publication of a short

treatise titled The Communist Manifesto, written by two

Germans, Karl Marx (1818--1883) and Friedrich Engels

(1820--1895).

Marxist Theory Marx and Engels began their treatise

with the statement that ‘‘the history of all hitherto ex-

isting society is the history of class struggles.’’ Throughout

history, then, oppressor and oppressed have ‘‘stood in

constant opposition to one another.’’

3

One group of

people---the oppressors---owned the means of production

and thus had the power to control government and so-

ciety. Indeed, government itself was but an instrument of

the ruling class. The other group, which depended on the

owners of the means of production, were the oppressed.

The class struggle continued in the industrialized

societies of Marx’s day. According to Marx, ‘‘Society as a

whole is more and more splitting up into two great

hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each

other: Bourgeoisie and Proletariat.’’ Marx predicted that

the struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat

would finally break into open revolution, ‘‘where the

violent overthrow of the bourgeoisie lays the foundation

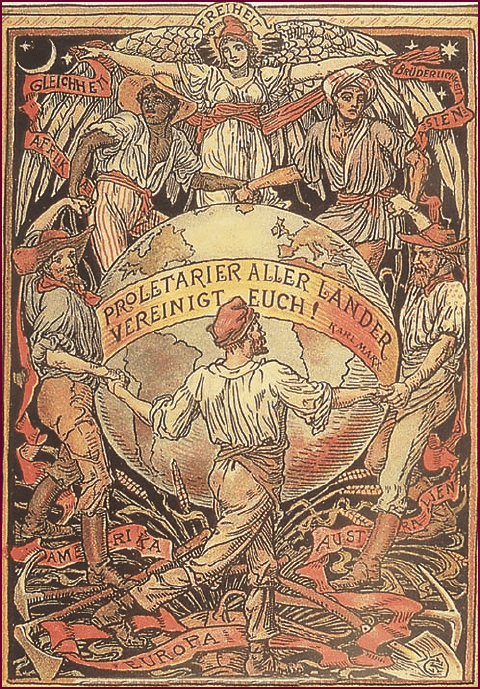

‘‘ Proletar ians of the World, Unite.’’ To improve their working

and living conditions, many industrial workers, inspired by the ideas of

Karl Marx, joined working-class or socialist parties. Pictured here is a

socialist-sponsored poster that proclaims in German the closing words of

The Communist Manifesto: ‘‘Proletarians of the World, Unite!’’

Photo courtesy of private collection

THE GROWTH OF INDUSTRIAL PROSPERITY 473

for the sway of the proletariat.’’ Hence the fall of the

bourgeoisie ‘‘and the victory of the proletariat are equally

inevitable.’’

4

For a while, the proletariat would form a

dictatorship in order to organize the means of produc-

tion, but the end result would be a classless society, since

classes themselves arose from the economic differences

that would have been abolished. The state---itself an in-

strument of the bourgeois interests---would wither away

(see the box above).

Socialist Parties In time, Marx’s ideas were picked up

by working-class leaders who formed socialist parties.

M ost important was the German Social Democratic Party

(SPD), which emerged in 1875 and espoused revolutionary

Marxist rhetoric while organizing itself as a mass political

party competing in elections for the Reichstag (the lower

house of parliament). Once in the Reichstag, SPD delegates

worked to achieve legislation to improve the condition of

the working class. When it received four million v otes in

the 1912 elections, the SPD became the largest single party

in Germany.

Socialist parties also emerged in other European

states. In 1889, leaders of the various socialist parties

formed the Second International, an association of

national socialist groups that would fight against capi-

talism worldwide. (The First International had failed in

1872.) The Second International took some coordinated

actions---May Day (May 1), for example, was made an

THE CLASSLESS SOCIETY

In The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and

Friedrich Engels projected that the end product

of the struggle between the bourgeoisie and the

proletariat would be the creation of a classless

society. In this selection, they discuss the steps by which that

classless society would be reached.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels,

The Communist Manifesto

We have seen ..., that the first step in the revolution by the working

class is to raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class. ...

The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degrees,

all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralize all instruments of pro-

duction in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organized

as the ruling class; and to increase the total of productive forces as

rapidly as possible.

Of course, in the beginning, this cannot be effected except by

means of despotic inroads on the rights of property, and on the

conditions of bourgeois production; by means of measures, there-

fore, which appear economically insufficient and untenable, but

which, in the course of the movement, outstrip themselves, necessi-

tate further inroads upon the old social order, and are unavoidable

as a means of entirely revolutionizing the mode of production.

These measures will of course be different in different countries.

Nevertheless, in the most advanced countries, the following will

be pretty generally applicable:

1. Abolition of property in land and application of all rents

of land to public purposes.

2. A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.

3. Abolition of all right of inheritance. ...

5. Centralization of credit in the hands of the St ate, by means

of a national bank w ith State capital and an exclusive

monopoly.

6. Centralization of the means of communication and transport

in the hands of the State.

7. Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by

the State. ...

8. Equal liability of all to labor. Establishment of industrial

armies, especially for agriculture.

9. Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries;

gradual abolition of the distinction between town and country,

by a more equable distribution of the population over the

country.

10. Free education for all children in public schools. Abolition of

children’s factory labor in its present form. ...

When, in the course of development, class distinctions have

disappeared, and all production has been concentrated in the whole

nation, the public power will lose its political character. Political

power, properly so called, is merely the organized power of one class

for oppressing another. If the proletariat during its contest w ith the

bourgeoisie is compelled, by the force of circumstances, to organize

itself as a class, if, by means of a revolution, it makes itself the rul-

ing class, and, as such, sweeps away by force the old conditions of

production, then it will, along with these conditions, have swept

away the conditions for the existence of class antagonisms and of

classes generally, and will thereby have abolished its own supremacy

as a class.

In place of the old bourgeois society, w ith its classes and

class antagonisms, we shall have an association, in which the free

development of each is the condition for the free development

of all.

Q

How did Marx and Engels define the proletariat? The

bourgeoisie? Why did Marxists come to believe that this

distinction was paramount for understanding history? For

shaping the future?

474 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

international labor holiday---but differences often wreaked

havoc at the organization’s congresses.

Marxist parties divided over the issue of revisionism.

Pure Marxists believed in the imminent collapse of cap-

italism and the need for socialist ownership of the means

of production. But others, called revisionists, rejected

revolutionary socialism and argued that workers must

organize mass political parties and work together with

other progressive elements to gain reform. Evolution by

democratic means, not revolution, would achieve the

desired goal of socialism.

Another force working for evolutionary rather than

revolutionary socialism was the development of trade

unions. In Great Britain, unions won the right to strike in

the 1870s. Soon after, the masses of workers in factories

were organized into trade unions so that they could use

the instrument of the strike. By 1900, there were two

million workers in British trade unions; by 1914, there

were almost four million union members. Trade unions

in the rest of Europe had varying degrees of success, but

by the outbreak of World War I, they had made consid-

erable progress in bettering both the living and the

working conditions of workers.

Reaction and Revolution:

The Growth of Nationalism

Q

Focus Questions: What were the major ideas

associated with conservatism, liberalism, and

nationalism, and what role did each ideology play in

Europe between 1800 and 1850? What were the causes

of the revolutions of 1848, and why did these

revolutions fail?

Industrialization was a major force for change in the

nineteenth century as it led the West into the machine-

dependent modern world. Another major force for

change was nationalism, which transformed the political

map of Europe in the nineteenth century.

The Conservative Order

After the defeat of Napoleon, European rulers moved to

restore much of the old order. This was the goal of the

great powers---Great Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia---

when they met at the Congress of Vienna in September

1814 to arrange a final peace settlement after the Napo-

leonic wars. The leader of the congress was the Austrian

foreign minister, Prince Klemens von Metternich (1773--

1859), who claimed that he was guided at Vienna by the

principle of legitimacy. To reestablish peace and stability

in Europe, he considered it necessary to restore the le-

gitimate monarchs who would preserve traditional in-

stitutions. This had already been done in France with the

restoration of the Bourbon monarchy and in a number of

other states, but it did not stop the great powers from

grabbing territory, often from the smaller, weaker states

(see Map 19.2).

The peace arrangements of 1815 were but the begin-

ning of a conservative reaction determined to contain the

liberal and nationalist for ces unleashed by the French

Re volution. Metternich and his kind were representativ es of

the ideology known as conservatism. Most conservatives

favored obedience to political authority, believed that or-

ganized religion was crucial to social order, hated revolu-

tionary upheavals, and were unwilling to acc ept either the

liberal demands for civil liberties and representativ e gov-

ernments or the nationalistic aspirations generated by the

French revolutionary era. After 1815, the political philos-

ophy of conservatism was supported by hereditary mon-

archs, government bureaucracies, landowning aristocracies,

and revived churches, both Protestant and Catholic. The

conservative forces were dominant after 1815.

One method used by the great powers to maintain the

new status quo they had constructed was the Concert of

Europe, according to which Great Britain, Russia, Prussia,

and Austria (and later France) agreed to meet periodically

in conferences to take steps that would maintain the peace

in Europe. Eventually, the great powers adopted a

principle of intervention, asserting that they had the right

to send armies into countries where there were revolutions

to restore legitimate monarchs to their thrones.

Forces for Change

Between 1815 and 1830, conservative gov ernments

throughout Europe worked to maintain the old order. But,

powerful forces for change---liberalism and nationalism---

were also at work. Liberalism owed much to the En-

lightenment of the eighteenth century and the American

and Fr ench Revolutions at the end of that century; it was

based on the idea that people should be as free from re-

straint as possible.

Liberals came to hold a common set of political

beliefs. Chief am ong them was the protection of civil

liberties, or the basic rights of all people, which included

equality before the law; freedom of assembly, speech,

and the press; and freedom from arbitrary arrest. All of

these freedoms should be guaranteed by a written doc-

ument, such as the American Bill of Rights. In add ition

to religious toleration for all, most liberals advocate d

separation of church and state. Liberals also deman ded

the right of peaceful opposition to the government in

and out of parliament and the making of laws by a

REACTION AND REVOLUTION:THE GROWTH O F NATIONALISM 475