Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

NAPOLEON AND PSYCHOLOGICAL WARFARE

In 1796, at the age of twenty-seven, Napoleon Bona-

parte was given command of the French army in Italy,

where he won a series of stunning victories. His use of

speed, deception, and surprise to overwhelm his oppo-

nents is well known. In this selection from a proclamation to his troops

in Italy, Napoleon also appea rs as a master of psychological warfare.

Napoleon Bonaparte, Proclamation to French Troops

in Italy (April 26, 1796)

Soldiers:

In a fortnight you have won six victories, taken twenty-one standards

[flags of military units], fifty-five pieces of artillery, several strong posi-

tions, and conquered the richest part of Piedmont [in northern Italy]; you

have captured 15,000 prisoners and killed or wounded more than 10,000

men. ... You have won battles without cannon, crossed rivers without

bridges, made forced marches without shoes, camped without brandy

and often without bread. Soldiers of liberty, only republican troops

could have endured what you have endured. Soldiers, you have our

thanks! The grateful Patrie [nation] will owe its prosperity to you. ...

The two armies which but recently attacked you with audacity

are fleeing before you in terror; the wicked men who laughed at

your misery and rejoiced at the thought of the triumphs of your

enemies are confounded and trembling.

But, soldiers, as yet you have done nothing compared with

what remains to be done. ... Undoubtedly the greatest obstacles

have been overcome; but you still have battles to fight, cities to cap-

ture, rivers to cross. Is there one among you whose courage is abat-

ing? No. ... All of you are consumed with a desire to extend the

glory of the French people; all of you long to humiliate those arro-

gant kings who dare to contemplate placing us in fetters; all of you

desire to dictate a glorious peace, one which will indemnify the

Patrie for the immense sacrifices it has made; all of you wish to be

able to say with pride as you return to your villages, ‘‘I was with the

victorious army of Italy!’’

Q

What themes did Napoleon use to play on the emotions of

his troops and inspire them to greater efforts? Do you think

Napoleon believed these words? Why or why not?

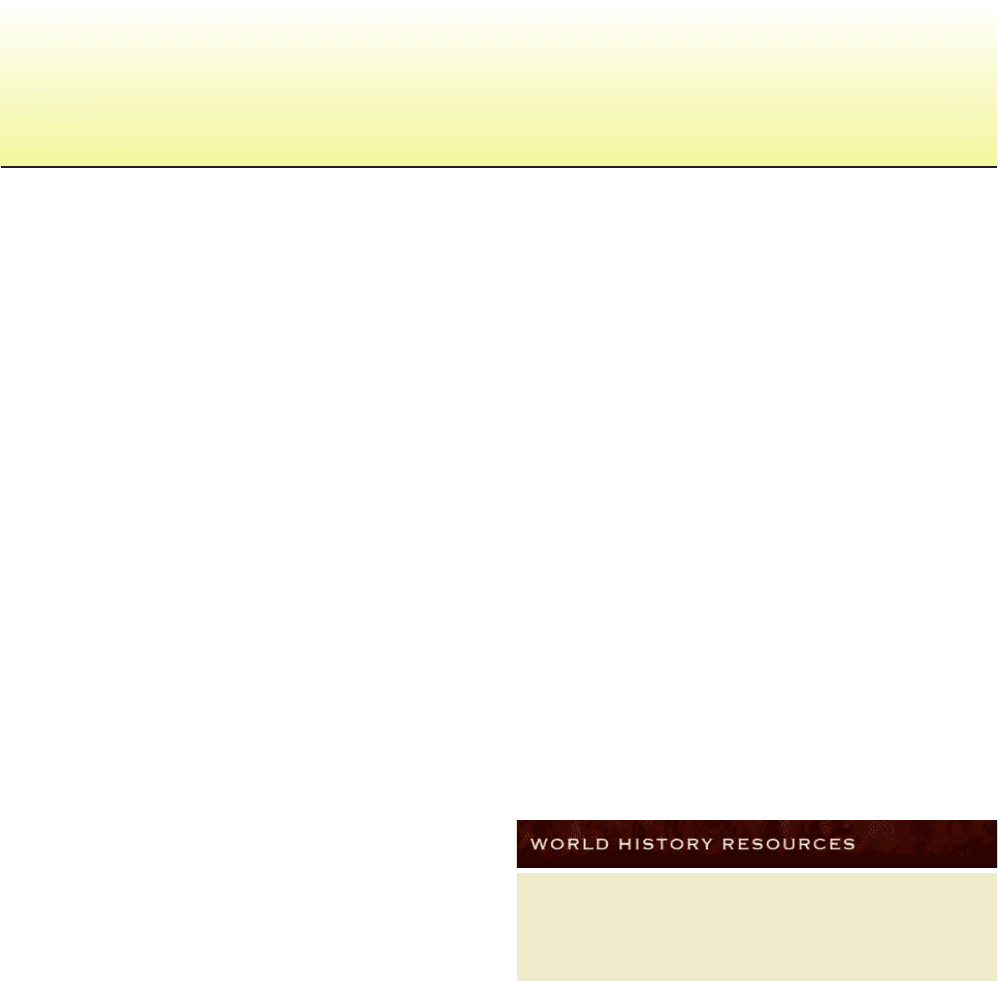

The Coronation of Napole on. In 1804, Napoleon restored monarchy to France when he became Emperor

Napoleon I. In the coronation scene painted by Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon is shown crowning his wife, the

empress Josephine, while the pope looks on. The painting shows Napoleon’s mother seated in the box in the

background, even though she was not at the ceremony.

c

R

eunion des Mus

ees Nationaux/Art Resource, NY

456 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

were now ‘‘less equal than men’’ in other ways as well.

When they married, their property came under the

control of their husbands.

Napoleon also developed a powerful, centralized

administrative machine and worked hard to develop a

bureaucracy of capable officials. Early on, the regime

showed that it cared little whether the expertise of offi-

cials had been acquired in royal or revolutionary bu-

reaucracies. Promotion, whether in civil or military

offices, was to be based not on rank or birth but on ability

only. This principle of a government career open to talent

was, of course, what many bourgeois had wanted before

the Revolution.

In his domestic policies, then, Napoleon both de-

stroyed and preserved a spects of the Revolution. Al-

though equality was preserved in the law code and the

opening of careers to talent, the creation of a new ar-

istocracy, th e strong protection accorded to property

rights, and the use of conscription for the military make

it clear that much equality had been lost. Liberty was

replaced by an initially benevolent despotism that grew

increasingly ar bitrary. Napoleon shut down sixty of

France’s seventy-three newspapers and insisted that all

manuscripts be subjected to government scrutiny before

they were published. Even the mail was opened by

government police.

Napoleon’s Empire

When Napoleon became consul in 1799, France was at

war with a second European coalition of Russia, Great

Britain, and Austria. Napoleon realized the need for a

pause and made a peace treaty in 1802. But in 1803 war

was renewed with Britain, which was soon joined by

Austria, Russia, and Prussia in the Third Coalition. In a

series of battles from 1805 to 1807, Napoleon’s Grand

Army defeated the Austrian, Prussian, and Russian ar-

mies, giving Napoleon the opportunity to create a new

European order.

The Grand Empire From 1807 to 1812, Napoleon was

the master of Europe. His Grand Empire was composed

of three major parts: the French Empire, dependent

states, and allied states (see Map 18.3). Dependent states

were kingdoms under the rule of Napoleon’s relatives;

these came to include Spain, the Netherlands, the king-

dom of Italy, the Swiss Republic, the Grand Duchy of

Warsaw, and the Confederation of the Rhine (a union of

all German states except Austria and Prussia). Allied

states were those defeated by Napoleon and forced to join

his struggle against Britain; these included Prussia, Aus-

tria, Russia, and Sweden.

Within his empire, Napoleon sought acceptance of

certain revolutionary principles, including legal equality,

religious toleration, and economic freedom. In the inner

core and dependent states of his Grand Empire, Napoleon

tried to destroy the old order. Nobility and clergy ev-

erywhere in these states lost their special privileges. He

decreed equality of opportunity with offices open to

talent, equality before the law, and religious toleration.

This spread of French revolutionary principles was an

important factor in the development of liberal traditions

in these countries.

Napoleon hoped that his Grand Empire would last

for centuries, but it collapsed almost as rapidly as it had

been formed. As long as Britain ruled the waves, it was

not subject to military attack. Napoleon hoped to in-

vade Britain, but he could not overcome the British

navy’s decisive defeat of a combine d French-Spanish

fleet at Trafalgar in 1805. To defeat Britain, Napoleon

turned to his Continental System. An alliance put into

effect between 1806 and 1808, it attempted to prevent

British goods from reaching the European continent in

order to weaken Britain economically and destroy its

capacity to wage war. But the Continental System failed.

Allied states resented i t; some began to cheat and others

to resist.

Napoleon also encountered new sources of opposi-

tion. His conquests made the French hated oppressors

and aroused the patriotism of the conquered people. A

Spanish uprising against Napoleon’s rule, aided by British

support, kept a French force of 200,000 pinned down for

years.

The Fall of Napoleon The beginning of Napoleon’s

downfall came in 1812 with his invasion of Russia. The

refusal of the Russians to remain in the Continental

System left Napoleon with little choice. Although aware of

the risks in invading such a huge country, he also knew

that if the Russians were allowed to challenge the Con-

tinental System unopposed, others would soon follow

suit. In June 1812, he led his Grand Army of more than

600,000 men into Russia. Napoleon’s hopes for victory

depended on quickly defeating the Russian armies, but

the Russian forces retreated and refused to give battle,

torching their own villages and countryside to keep Na-

poleon’s army from finding food. When the Russians did

stop to fight at Borodino, Napoleon’s forces won an

indecisive and costly victory. When the remaining troops

of the Grand Army arrived in Moscow, they found the

city ablaze. Lacking food and supplies, Napoleon aban-

doned Moscow late in October and made a retreat across

Russia in terrible winter conditions. Only 40,000 of the

original 600,000 men managed to arrive back in Poland in

January 1813.

THE AGE OF NAPOLEON 457

This military disaster led other E uropean states to rise up

and attack the crippled French army. P aris was captured in

March 1814, and N apoleon was sent into exile on the island

of Elba, off the coast of Italy. Mean while, the Bourbon

monarch y was restored in the person of Louis XVIII, the

count of Pro venc e, brother of the executed king. (Louis XVII,

son of Louis XVI, had died in prison at age ten.) Napoleon,

bored on Elba, slipped back into France. When troops were

sent to capture him, Napoleon opened his coat and ad-

dressed them: ‘‘Soldiers of the 5th regiment, I am your

Emperor. ... If there is a man among you would kill his

Emperor, here I am!’’ No one fired a shot. Shouting ‘‘Vive

l’Empereur! Vive l’Empereur!’’ the troops went ov er to his side,

and N apoleon entered P aris in triumph on March 20, 1815.

The powers that had defeated him pledged once

more to fight him. Having decided to strike first at his

enemies, Napoleon raised yet another army and moved to

attack the allied forces stationed in what is now Belgium.

At Waterloo on June 18, Napoleon met a combined

British and Prussian army under the duke of Wellington

and suffered a bloody defeat. This time, the victorious

allies exiled him to Saint Helena, a small, forsaken island

in the South Atlantic, off the coast of Africa. Only Na-

poleon’s memory continued to haunt French political life.

Leipzig 1813

Borodino 1812

Friedland 1807

Eylau 1807

Austerlitz 1805

Auerstadt 1806

Jena 1806

Waterloo 1815

Ulm 1805

Trafalgar 1805

Corsica

Sardinia

Crete

Cyprus

Malta

P

y

r

e

n

e

e

s

A

l

p

s

T

a

u

r

u

s

M

t

s

.

Atlantic

Ocean

Black Sea

North

Sea

Mediterranean Sea

B

a

l

t

i

c

S

e

a

B

a

l

e

a

r

i

c

I

s

l

a

n

d

s

Marseilles

Berlin

Moscow

Smolensk

Tilsit

Danzig

Kiev

Pressburg

Zürich

Copenhagen

London

Brussels

Paris

Milan

Genoa

Rome

Elba

Madrid

Lisbon

Vienna

Cairo

Warsaw

FRENCH

EMPIRE

RUSSIAN

EMPIRE

AUSTRIAN

EMPIRE

OTTOMAN

EMPIRE

KINGDOM

OF SICILY

KINGDOM

OF NAPLES

KINGDOM

OF

ITALY

EGYPT

SPAIN

PORTUGAL

GREAT

BRITAIN

NORWAY

SWEDEN

DENMARK

SAXONY

PRUSSIA

ILLYRIAN

PROVINCES

SWITZERLAND

GRAND DUCHY

OF WARSAW

CONFEDERATION OF

THE RHINE

E

b

r

o

R

.

R

h

i

n

e

R

.

P

o

R

.

D

a

n

u

b

e

R

.

D

n

i

e

p

e

r

R

.

D

n

i

e

s

t

e

r

R.

0 250 500 Miles

0 250 500 750 Kilometers

French Empire

Under French control

Allied to France

Napoleon’s route, 1812

Battle site

MAP 18.3 Napoleon’s Grand Empire. Napoleon’s Grand Army won a series of victories

against Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia that gave the French emperor full or partial control

over much of Europe by 1807.

Q

On the Continent, what was the overall relationship between distance from France and

degree of Fr ench control, and how can you account for this?

458 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

CONCLUSION

THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION was a major turning point in

modern civilization. With a new conception of the universe came a

new conception of humankind and the belief that by using reason

alone people could understand and dominate the world of nature.

In combination with the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, the

Scientific Revolution gave the West an intellectual boost that

contributed to the increased confidence of Western civilization.

Europeans---with their strong governments, prosperous economies,

and strengthened military forces---began to dominate other parts of

the world, leading to a growing belief in the superiority of their

civilization.

Everywhere in Europe at the beginning of the eighteenth

century, the old order remained strong. Monarchs sought to enlarge

their bureaucracies to raise taxes to support the large standing

armies that had originated in the seventeenth century. The existence

of five great powers, with two of them (France and Great Britain)

embattled in the East and in the Western Hemisphere, ushered in a

new scale of conflict; the Seven Years’ War can legitimately be

viewed as the first world war. Throughout Europe, increased

demands for taxes to support these conflicts led to attacks on the

privileged orders and a desire for change not met by the ruling

monarchs. The inability of that old order to deal meaningfully with

this desire for change led to a revolutionary outburst at the end of

the eighteenth century that brought the old order to an end.

The revolutionary era of the late eighteenth century was a time

of dramatic political transformations. Revolutionary upheavals,

beginning in North America and continuing in France, spurred

movements for political liberty and equality. The documents

promulgated by these revolutions, the Declaration of Independence

and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, embodied

the fundamental ideas of the Enlightenment and created a liberal

political agenda based on a belief in popular sovereignty---the

people as the source of political power---and the principles of liberty

and equality. Liberty meant, in theory, freedom from arbitrary

power as well as the freedom to think, write, and worship as one

chose. Equality meant equality in rights and equality of opportunity

based on talent rather than wealth or status at birth. In practice,

equality remained limited; property owners had greater opportu-

nities for voting and office holding, and women were still not

treated as the equals of men.

TIMELINE

1600

1650 1700 1750 1800 1850

Reign of Frederick the Great

Reign of Terror

in France

Storming of the Bastille

Seven Years’ War

Napoleon becomes emperor

American Declaration of Independence

Galileo, The Starry Messenger

Work of Sor Juana

Inéz de la Cruz

Work of Watteau Reform program

of Joseph II

Battle of Waterloo

Rousseau, The Social Contract

Work of Isaac Newton

Diderot,

Encyclopedia

CONCLUSION 459

SUGGESTED READING

Intellectual Revolution in the West Two general surveys of

the Scientific Revolution are J. R. Jacob, The Scientific Revolution:

Aspirations and Achievements, 1500--1700 (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.,

1998), and J. Henry, The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of

Modern Science, 2nd ed. (New York, 2002). Good introductions to

the Enlightenment can be found in U. Im Hof, The Enlightenment

(Oxford, 1994), and D. Outram, The Enlightenment, 2nd ed.

(Cambridge, 2005). See also the beautifully illustrated work by

D. Outram, Panorama of the Enlightenment (Los Angeles, 2006),

and M. Fitzpatrick et al., The Enlightenment World (New York,

2004). On the social history of the Enlightenment, see T. Munck,

The Enlightenment: A Comparative Social History, 1721--1794

(London, 2000). On women in the eighteenth century, see M. E.

Wiesner-Hanks, Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe

(Cambridge, 2000). On culture, see E. Gesine and J. F. Walther,

Rococo (New York, 2007).

The Social Order On the European nobility in the eighteenth

century, see J. Dewald, The European Nobility, 1400--1800, 2nd ed.

(Cambridge, 2004). On European cities, see J. de Vries, European

Urbanization, 1500--1800 (Cambridge, Mass., 1984).

Colonial Empires For a brief survey of Latin America, see

E. B. Burns and J. A. Charlip, Latin America: An Interpretive

History, 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J., 2007). A more detailed

work on colonial Latin American history is J. Lockhardt and

S. B. Schwartz, Early Latin America: A History of Colonial

Spanish America and Brazil (New York, 1983). A history of the

revolutionary era in America can be found in S. Conway, The

War of American Independence, 1775--1783 (New York, 1995).

Enlightened Absolutism and Global Conflict On

enlightened absolutism, see D. Beales, Enlightenment and Reform

in Eighteenth-Century Europe (New York, 2005). Good biographies

of some of Europe’s monarchs include G. MacDonough, Frederick

the Great (New York, 2001); I. De Madariaga, Catherine the Great:

A Short History (New Haven, Conn., 1990); and T. C. W. Blanning,

Joseph II (New York, 1994).

The French Revolution A well-written, up-to-date

introduction to the French Revolution can be found in W. Doyle,

The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 2nd ed. (Oxford,

2003). On the entire revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, see

O. Connelly, The French Revolution and Napoleonic Era, 3rd ed.

(Fort Worth, Tex., 2000). On the radical stage of the French

Revolution, see D. Andress, The Terror: The Merciless War for

Freedom in Revolutionary France (New York, 2005), and R. R.

Palmer, Twelve Who Ruled (Princeton, N.J., 1965), a classic. On the

role of women in revolutionary France, see O. Hufton, Women and

the Limits of Citizenship in the French Revolution (Toronto, 1992).

The Age of Napoleon The best biography of Napoleon is

S. Englund, Napoleon: A Political Life (New York, 2004). Also

valuable are G. J. Ellis, Napoleon (New York, 1997); M. Lyons,

Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution

(New York, 1994); and the massive biographies by F. J. McLynn,

Napoleon: A Biography (London, 1997), and A. Schom, Napoleon

Bonaparte (New York, 1997).

The French Revolution set in motion a modern revolutionary

concept. No one had foreseen or consciously planned the upheaval

that began in 1789, but thereafter, radicals and revolutionaries knew

that mass uprisings by the common people could overthrow

unwanted elitist governments. For these people, the French

Revolution became a symbol of hope; for those who feared such

changes, it became a symbol of dread. The French Revolution

became the classic political and social model for revolution. At the

same time, the liberal and national political ideals created by the

Revolution dominated the political landscape for well over a

century. A new era had begun, and the world would never be the

same.

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

460 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

461

PART

IV

M

ODERN

P

ATTERNS

OF

W

ORLD

H

ISTORY

(1800--1945)

19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION:

I

NDUSTRIALIZATION AND NATIONALISM

IN THE

NINETEENTH CENTURY

20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY

AND

CULTURE IN THE WEST

21 THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

22 SHADOWS OVER THE PACIFIC:

E

AST ASIA UNDER CHALLENGE

23 THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTIETH-

C

ENTURY CRISIS:WAR AND REVOLUTION

24 NATIONALISM,REVOLUTION, AND

DICTATORSHIP:ASIA, THE MIDDLE EAST,

AND LATIN AMERICA FROM 1919 TO

1939

25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS:WORLD WAR II

THE PERIOD OF WORLD HISTORY from 1800 to 1945 was

characterized by three major developments: the growth of indus-

trialization, Western domination of the world, and the rise of

nationalism. The three developments were, of course, interconnected.

The Industrial Revolution became one of the major forces of change in

the nineteenth century as it led Western civilization into the industrial

era that has characterized the modern world. Beginning in Britain, it

spread to the Continent and the Western Hemisphere in the course of

the nineteenth century. At the same time, the Industrial Revolution

created the technological means, including new weapons, by which the

West achieved domination of much of the rest of the world by the end

of the nineteenth century. Moreover, the existence of competitive

European nation-states after 1870 was undoubtedly a major determi-

nant in leading European states to embark on their intense scramble for

overseas territory.

The advent of the industrial age had a number of lasting con-

sequences for the world at large. On the one hand, the material wealth

of the nations that successfully passed through the process increased

significantly. In many cases, the creation of advanced industrial soci-

eties strengthened democratic institutions and led to a higher standard

of living for the majority of the population. On the other hand, not all

the consequences of the Industrial Revolution were beneficial. In the

industrializing societies themselves, rapid economic change often led to

widening disparities in the distribution of wealth and, with the decline

in pervasiveness of religious belief, a sense of rootlessness and alien-

ation among much of the population.

A second development that had a major impact on the era was the

rise of nationalism. Like the Industrial Revolution, the idea of

nationalism originated in eighteenth-century Europe, where it was a

product of the secularization of the age and the experience of the

French revolutionary and Napoleonic eras. Although the concept

provided the basis for a new sense of community and the rise of the

modern nation-state, it also gave birth to ethnic tensions and hatreds

that resulted in bitter disputes and civil strife and contributed to the

competition that eventually erupted into world war.

Industrialization and the rise of national consciousness also

transformed the nature of war itself. New weapons of mass destruction

created the potential for a new kind of warfare that reached beyond the

battlefield into the very heartland of the enemy’s territory, while the

462

concept of nationalism transformed war from the sport of kings to a

matter of national honor and commitment. Since the French Revolu-

tion, governments had relied on mass conscription to defend the

national cause, while their engines of destruction reached far into

enemy territory to destroy the industrial base and undermine the will

to fight. This trend was amply demonstrated in the two world wars of

the twentieth century.

In the end, then, industrial power and the driving force of na-

tionalism, the very factors that had created the conditions for European

global dominance, contained the seeds for the decline of that domi-

nance. These seeds germinated during the 1930s, when the Great

Depression sharpened international competition and mutual antago-

nism, and then sprouted in the ensuing conflict, which for the first time

spanned the entire globe. By the time World War II came to an end, the

once powerful countries of Europe were exhausted, leaving the door

ajar for the emergence of two new global superpowers, the United

States and the Soviet Union, and for the collapse of the Europeans’

colonial empires.

Europeans had begun to explore the world in the fifteenth cen-

tury, but even as late as 1870, they had not yet completely penetrated

North America, South America, Australia, or most of Africa. In Asia

and Africa, with few exceptions, the Western presence was limited to

trading posts. Between 1870 and 1914, Western civilization expanded

into the rest of the Americas and Australia, while the bulk of Africa and

Asia was divided into European colonies or spheres of influence. Two

major events explain this remarkable expansion: the migration of many

Europeans to other parts of the world due to population growth and

the revival of imperialism, which was made possible by the West’s

technological advances. Beginning in the 1880s, European states began

an intense scramble for overseas territory. This revival of imperialism---

the ‘‘new imperialism,’’ some have called it---led Europeans to carve up

Asia and Africa.

What was the overall economic effect of imperialism on the

subject peoples? For most of the population in colonial areas, Western

domination was rarely beneficial and often destructive. Although a

limited number of merchants, large landowners, and traditional he-

reditary elites undoubtedly prospered under the umbrella of the ex-

panding imperialistic economic order, the majority of colonial peoples,

urban and rural alike, probably suffered considerable hardship as a

result of the policies adopted by their foreign rulers.

Some historians point out, however, that for all the inequities of

the colonial system, there was a positive side to the experience as well.

The expansion of markets and the beginnings of a modern transpor-

tation and communications network, while bringing few immediate

benefits to the colonial peoples, offered considerable promise for future

economic growth. At the same time, colonial peoples soon learned the

power of nationalism, and in the twentieth century, nationalism would

become a powerful force in the rest of the world as nationalist revo-

lutions moved through Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Moreover, the

exhaustive struggles of two world wars sapped the power of the Eu-

ropean states, and the colonial powers no longer had the energy or the

wealth to maintain their colonial empires after World War II.

c Art Media, Victoria and Albert Museum, London/HIP/The Image Works

MODERN PATTERNS OF W ORLD HISTORY (1800--1945) 463

CHAPTER 19

THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION: INDUSTRIALIZATION

AND NATIONALISM IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

The Industrial Revolution and Its Impact

Q

What were the basic features of the new industrial

system created by the Industrial Revolution, and what

effects did the new system have on urban life, social

classes, family life, and standards of living?

The Growth of Industrial Prosperity

Q

What was the Second Industrial Revolution, and what

effects did it have on economic and social life? What

were the main ideas of Karl Marx, and what role did

they play in politics and the union movement in the

late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries?

Reaction and Revolution: The Growth of Nationalism

Q

What were the major ideas associated with

conservatism, liberalism, and nationalism, and what

role did each ideology play in Europe between 1800

and 1850? What were the causes of the revolutions of

1848, and why did these revolutions fail?

National Unification and the National State, 1848--1871

Q

What actions did Cavour and Bismarck take to bring

about unification in Italy and Germany, respectively,

and what role did war play in their efforts?

The European State, 1871--1914

Q

What general political trends were evident in the nations

of western Europe in the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries, and to what degree were those

trends also apparent in the nations of central and

eastern Europe? How did the growth of nationalism

affect international affairs during the same period?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

In what ways was the development of industrialization

related to the growth of nationalism?

A meeting of the Congress of Vienna

c

Scala/Art Resource, NY

464

IN SEPTEMBER 1814, hundreds of foreigners began to con-

verge on Vienna, the capital city of the Austrian Empire. Many were

members of European royalty---kings, archdukes, princes, and their

wives---accompanied by their diplomatic advisers and scores of ser-

vants. Their congenial host was the Austrian emperor, Francis I, who

never tired of regaling Vienna’s guests with concerts, glittering balls,

sumptuous feasts, and innumerable hunting parties. One participant

remembered, ‘‘Eating, fireworks, public illuminations. For eight or

ten days, I haven’t been able to work at all. What a life!’’ Of course,

not every waking hour was spent in pleasure during this gathering

of notables, known to history as the Congress of Vienna. The guests

were also representatives of all the states that had fought Napoleon,

and their real business was to arrange a final peace settlement after

almost a decade of war. On June 8, 1815, they finally completed

their task.

The forces of upheaval unleashed during the French revolution-

ary and Napoleonic wars were temporarily quieted in 1815 as rulers

sought to restore stability by reestablishing much of the old order to

a Europe ravaged by war. But the Western world had been changed,

and it would not readily go back to the old system. New ideologies

of change, especially liberalism and nationalism, products of the up-

heaval initiated in France, had become too powerful to be contained.

The Industrial Revolution

and Its Impact

Q

Focus Question: What were the basic features of the

new industrial system created by the Industrial

Revolution, and what effects did the new system have

on urban life, social classes, family life, and standards

of living?

Dur ing the Industrial Revolution, Europe shifted from

an economy based on agriculture and handicrafts to an

economy based on manufacturin g by machines and

automated factories. The Industrial Revolution trig-

gered an enormous leap in industrial production that

relied largely on coal and steam, which replaced wind

and water as new sources of energy an d power to drive

laborsaving machines. In turn, these machines called for

new ways of organizing human labor to maximize the

benefits and profits from the new machines. As factories

replaced shop and home workrooms, larg e num bers of

people moved from the countryside to the cities to work

in the new factories. The creation of a wealthy industrial

middle class and a hug e industrial working class (or

proletariat) substantially transformed traditional social

relationships.

The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain

The Industrial Revolution began in Britain in the 1780s.

Improvements in agricultural practices in the eighteenth

century led to a significant increase in food production.

British agriculture could now feed more people at lower

prices with less labor; even ordinary British families did

not have to use most of their income to buy food, giving

them the wherewithal to purchase manufactured goods.

At the same time, rapid population growth in the second

half of the eighteenth century provided a pool of surplus

labor for the new factories of the emerging British

industry.

A crucial factor in Britain’s successf ul industriali-

zation was the ability to produce cheaply the articles in

greatest demand. The traditional methods of cottage

industry could not keep up w ith the growing demand

for cotton clothes throughout Britain and its vast co-

lonial empire. Faced with this problem, Bri tish cloth

manufacturer s sought and accep ted t he new methods o f

manufacturing that a series of inventions p rovided.

In so doing, these indiv iduals ignited the Industrial

Revolution.

Changes in Textile Production The invention of the

flying shuttle enabled weavers to weave faster on a loom,

thereby doubling their output. This created shortages of

yarn until James Hargreaves’s spinning jenny, perfected by

1768, allowed spinners to produce yarn in greater quan-

tities. Edmund Cartwright’s loom, powered by water and

invented in 1787, allowed the weaving of cloth to catch

up with the spinning of yarn. It was now more efficient to

bring workers to the machines and organize their labor

collectively in factories located next to rivers and streams,

the sources of power for these early machines.

The invention of the steam engine pushed the cotton

industry to even greater heights of productivity. In the

1760s, a Scottish engineer, James Watt (1736--1819), built

an engine powered by steam that could pump water from

mines three times as quickly as previous engines. In 1782,

Watt developed a rotary engine that could turn a shaft

and thus drive machinery. Steam power could now be

applied to spinning and weaving cotton, and before long,

cotton mills using steam engines were multiplying across

Britain. Fired by coal, these steam engines could be

located anywhere.

The boost given to cotton textile production by these

technological changes was readily apparent. In 1760,

Britain had imported 2.5 million pounds of raw cotton,

which was farmed out to cottage industries. In 1787, the

British imported 22 million pounds of cotton; most of it

was spun on machines, some powered by water in large

mills. By 1840, some 366 million pounds of cotton---now

Britain’s most important product in value---were being

imported. By this time, British cotton goods were sold

everywhere in the world.

Other Technological Changes The British iron indus-

try was also radically transformed during the Industrial

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION AND ITS IMPACT 465

The forces of change called forth revolts that periodically shook the

West and culminated in a spate of revolutions in 1848. Some of the

revolutions and revolutionaries were successful; most were not. And

yet by 1870, many of the goals sought by the li berals and national-

ists during the first half of the nineteenth century seemed to have

been achieved. National unity became a reality in Italy and Ger-

many, and many Western states develo ped parliamentary features.

Between 1870 and 1914, these newly constituted states experienced

a time of great tension. Europeans engaged in a race for colonies

that intensified existing antagonisms among the European states,

while the creation of huge cons cript armies and enormous military

establishments served to heighten tensions among the major

powers.

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, an-

other revolution---an industrial one---transformed the economic and

social structure of Europe and spawned the industrial era that has

characterized modern world history.