Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A New Age of Science

With the Industrial Revolution came a renewed interest in

basic scientific research. By the 1830s, new scientific

discoveries led to many practical benefits that caused

science to have an ever-greater impact on European life.

In biology, the Frenchman Louis Pasteur (1822--

1895) discovered the germ theory of disease, which had

enormous practical applications in the development of

modern scientific medical practices. In chemistry, the

Russian Dmitri Mendeleev (1834--1907) in the 1860s

classified all the material elements then known on the

basis of their atomic weights and provided the systematic

foundation for the periodic law.

The popularity of scientific and technological

achievement produced a widespread acceptance of the

scientific method as the only path to objective truth and

objective reality. This in turn undermined the faith of

many people in religious revelation. It is no accident that

the nineteenth century was an age of increasing secular-

ization, evident in the belief that truth was to be found in

the concrete material existence of human beings. No one

did more to create a picture of humans as material beings

that were simply part of the

natural world than Charles

Darwin.

In 1859, Charles Darwin

(1809--1882) published On

the Origin of Species by Means

of Natural Selection. The basic

idea of this book was that all

plants and animals had each

evolved over a long period of

time from earlier and simpler

forms of life, a principle

known as organic evolution.

In every species, he argued,

‘‘many more individuals of

each species are born than can

possibly survive.’’ This results

in a ‘‘struggle for existence.’’

Darwin believed that some

organisms were more adapt-

able to the environment than

others, a process that Darwin

called natural selection.

Those that were naturally se-

lected for survival (‘‘survival

of the fit’’) reproduced and

thrived. The unfit did not and

became extinct. The fit who

survived passed on small var-

iations that enhanced their

survival until, from Darwin’s point of view, a new and

separate species emerged. In The Descent of Man, pub-

lished in 1871, he argued for the animal origins of human

beings. Humans were not an exception to the rule gov-

erning other species.

Realism in Literature and Art

The name Realism was first employed in 1850 to describe

a new style of painting and soon spread to literature. The

literary Realists of the mid-nineteenth century rejected

Romanticism. They wanted to deal with ordinary char-

acters from actual life rather than Romantic heroes in

exotic settings.

The leading novelist of the 1850s and 1860s, the

Frenchman Gustave Flaubert (1821--1880), perfected the

Realist novel. His Madame Bovary (1857) was a

straightforward description of barren and sordid pro-

vincial life in France. Emma Bovary is trapped in a

marriage to a drab provincial doctor. Impelled by the

images of romantic love she has read about in novels, she

seeks the same thing for herself in adulterous love affairs

but is ultimately driven to suicide.

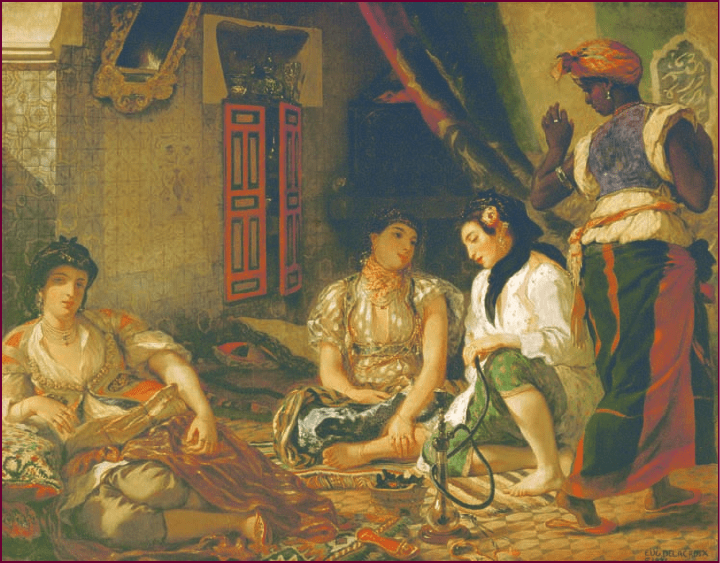

Eug

ene Delacroix, Women of A lgiers. A characteristic of Romanticism was its love of the exotic and

unfamiliar. In his Women of Algiers, Delacroix reflected this fascination with the exotic. In this portrayal of

harem concubines from North Africa, the clothes and jewelry of the women combine with their calm facial

expressions to create an atmosphere of peaceful sensuality. At the same time, Delacroix’s painting reflects his

preoccupation with light and color.

c

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

506 CHAPTER 20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

Realism also made inroads into the Latin American

literary scene by the second half of the nineteenth cen-

tury. There, Realist novelists focused on the injustices of

their society, evident in the work of Clorinda Matto de

Turner (1852--1909). Her Aves sin Nido (Birds without a

Nest) was a brutal revelation of the pitiful living con-

ditions of the Indians in Peru. She especially blamed the

Catholic church for much of their misery.

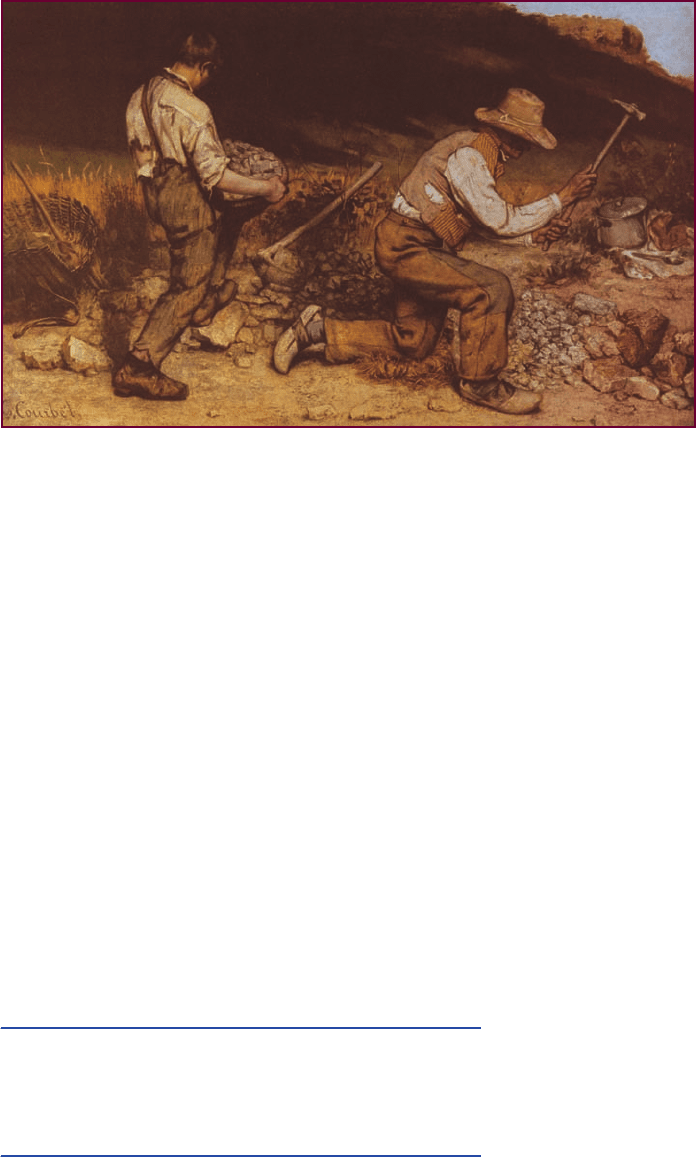

In art, too, Realism became dominant after 1850.

Gustave Courbet (1819--1877), the most famous artist of

the Realist school, reveled in realistic portrayals of every-

day life. His subjects were factory workers, peasants, and

the wives of saloonkeepers. ‘‘I have never seen either angels

or goddesses, so I am not interested in painting them,’’ he

exclaimed. One of his famous works, The Stonebreakers,

painted in 1849, shows two road workers engaged in the

deadening work of breaking stones to build a road.

Toward the Modern

Consciousness: Intellectual

and Cultural Developments

Q

Focus Question: What intellectual and cultural

developments in the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries ‘‘opened the way to a modern

consciousness,’’ and how did this consciousness differ

from earlier worldviews?

Before 1914, many people in the Western world contin-

ued to believe in the values and ideals that had been

generated by the Scientific Revolution and the Enlight-

enment. The idea that human beings could improve

themselves and achieve a better society seemed to be

proved by a rising standard of living, urban comforts, and

mass education. It was easy to think that the human mind

could make sense of the universe. Between 1870 and 1914,

though, radically new ideas challenged these optimistic

views and opened the way to a modern consciousness.

A New Physics

Science was one of the chief pillars underlying the opti-

mistic and rationalistic view of the world that many

Westerners shared in the nineteenth century. Supposedly

based on hard facts and cold reason, science offered a

certainty of belief in the orderliness of nature. The new

physics dramatically altered that perspective.

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, West-

erners adhered to the mechanical conception of the uni-

verse postulated by the classic physics of Isaac Newton.

In this perspective, the universe was viewed as a giant

machine in which time, space, and matter were objective

realities that existed independently of the observers.

Matter was thought to be composed of indivisible and

solid material bodies called atoms.

Albert Einstein (1879--1955), a German-born patent

officer working in Switzerland, questioned this view of the

universe. In 1905, Einstein published his special theory of

relativity, which stated that space and time are not absolute

but relative to the observer. Neither space nor time had an

existence independent of human experienc e. As Einstein

later explained simply to a journalist: ‘‘It was formerly

believed that if all material things disappeared out of the

universe, time and space would be left. Accor ding to the

relativity theory, however, time and space disappear

Gustave Cou rbet, The

Stonebreakers. Realism, largely

developed by French painters, aimed at a

lifelike portrayal of the daily activities of

ordinary people. Gustave Courbet was the

most famous of the Realist artists. As is

evident in The Stonebreakers, he sought to

portray things as they really appear. He

shows an old road builder and his young

assistant in their tattered clothes,

engrossed in their dreary work of breaking

stones to construct a road.

c

Oskar Reinhart Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library

TOWAR D T HE MODERN CONSCIOUSNESS:INTELLECTUAL AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS 507

together with the things.’’

7

Einstein concluded that matter

was nothing but another form of energy. His epochal

formula E = mc

2

---stating that each particle of matter is

equivalent to its mass times the square of the velocity of

light---was the key theory explaining the vast energies

contained within the atom. It led to the atomic age.

Sigmund Freud and the Emergence

of Psychoanalysis

At the turn of the twentieth centur y, Viennese physician

Sigmund Freud (1856--1939) advanced a series of the-

ories that undermined optimism about the rational

nature of the human mind. Freud’s thought, like the

new physics, added to the uncertainties of the age. His

major ideas were published in 1900 in The Interpreta-

tion of Dreams.

According to Freud, human behavior was strongly

determined by the unconscious, by past experiences and

internal forces of which people were largely oblivious.

For Freud, human behavior was no longer truly rational

but rather instinctive or irrational. He argued that painful

and unsettling experiences were blotted from conscious

awareness but still continued to influence behavior since

they had become part of the unconscious (see the box

above). Repression began in childhood. Freud devised a

method, known as psychoanalysis, by which a psycho-

therapist and patient could probe deeply into the mem-

ory in order to retrace the chain of repression all the way

back to its childhood origins. By making the conscious

mind aware of the unconscious and its repressed con-

tents, the patient’s psychic conflict was resolved.

The Impact of Darwin:

Social Darwinism and Racism

In the second half of the nineteenth century, scientific

theories were sometimes wrongly applied to achieve other

ends. For example, Charles Darwin’s principle of organic

evolution was applied to the social order as social

FREUD AND THE CONCEPT OF REPRESSION

Freud’s psychoanalytical theories resulted from his

attempt to understand the world of the uncon-

scious. This excerpt is taken from a lecture given

in 1909 in which Freud describes how he arrived

at his theory of the role of repression.

Sigmund Freud, Five Lectures on Psychoanalysis

I did not abandon [the technique of encouraging patients to reveal

forgotten experiences], however, before the observations I made dur-

ing my use of it afforded me decisive evidence. I found confirmation

of the fact that the forgotten memories were not lost. They were in

the patient’s possession and were ready to emerge in association to

what was still known by him; but there was some force that pre-

vented them from becoming conscious and compelled them to re-

main unconscious. The existence of this force could be assumed

with certainty, since one became aware of an effort corresponding to

it if, in opposition to it, one tried to introduce the unconscious

memories into the patient’s consciousness. The force which was

maintaining the pathological condition became apparent in the form

of resistance on the part of the patient.

It was on this idea of resistance, then, that I based my view of

the course of psychical events in hysteria. In order to effect a recov-

ery, it had proved necessary to remove these resistances. Starting out

from the mechanism of cure, it now became possible to construct

quite definite ideas of the origin of the illness. The same forces

which, in the form of resistance, were now offering opposition to

the forgotten material’s being made conscious, must formerly have

brought about the forgetting and must have pushed the pathogenic

experiences in question out of consciousness. I gave the name of

‘‘repression’’ to this hypothetical process, and I considered that it

was proved by the undeniable existence of resistance.

The further question could then be raised as to what these

forces were and what the determinants were of the repression in

which we now recognized the pathogenic mechanism of hysteria. A

comparative study of the pathogenic situations which we had come

to know through the cathartic procedure made it possible to answer

this question. All these experiences had involved the emergence of a

wishful impulse which was in sharp contrast to the subject’s other

wishes and which proved incompatible with the ethical and aesthetic

standards of his personality. There had been a short conflict, and

the end of this internal struggle was that the idea which had

appeared before consciousness as the vehicle of this irreconcilable

wish fell a victim to repression, was pushed out of consciousness

with all its attached memories, and was forgotten. Thus, the incom-

patibility of the wish in question with the patient’s ego was the mo-

tive for the repression; the subject’s ethical and other standards were

the repressing forces. An acceptance of the incompatible wishful im-

pulse or a prolongation of the conflict would have produced a high

degree of unpleasure; this unpleasure was avoided by means of re-

pression, which was thus revealed as one of the devices serving to

protect the mental personality.

Q

According to Freud, how did he discover the existence of

repression? What function does repression perform?

508 CHAPTER 20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

Darwinism, the belief that societies were organisms that

evolved through time from a struggle with their envi-

ronment. Such ideas were used in a radical way by rabid

nationalists and racists. In their pursuit of national

greatness, extreme nationalists insisted that nations, too,

were engaged in a ‘‘struggle for existence’’ in which only

the fittest survived.

Anti-Semitism Anti-Semitism had a long history in

European civilization, but in the nineteenth century, as a

result of the ideals of the Enlightenment and the French

Revolution, Jews were increasingly granted legal equality

in many European countries. Many Jews now left the

ghetto and became assimilated into the cultures around

them. Many became successful as bankers, lawyers, sci-

entists, scholars, journalists, and stage performers.

These achievements represent only one side of the

picture, however. In Germany and Austria during the 1880s

and 1890s, conservatives founded right-wing anti-Jewish

parties that used anti-Semitism to win the votes of

traditional lower -middle-class groups who felt threatened

by the new economic forces of the times. The worst treat-

ment of Jews at the turn of the century, howev er, occurred in

eastern Eur ope, where 72 perc ent of the entire world Jewish

population lived. Russian Jews were forced to live in certain

regions of the country , and persecutions and pogroms were

widespread. Hundreds of thousands of J ews decided to

emigrate to escape

the persecution.

Man y Jews went

to the United States,

although some

mov ed to Palestine,

which soon became

the focus of a Jewish

nationalist move-

ment called Zionism.

For many Jews, Pal-

estine, the land of

ancient Israel, had

COMPARATIVE ILLUSTRATION

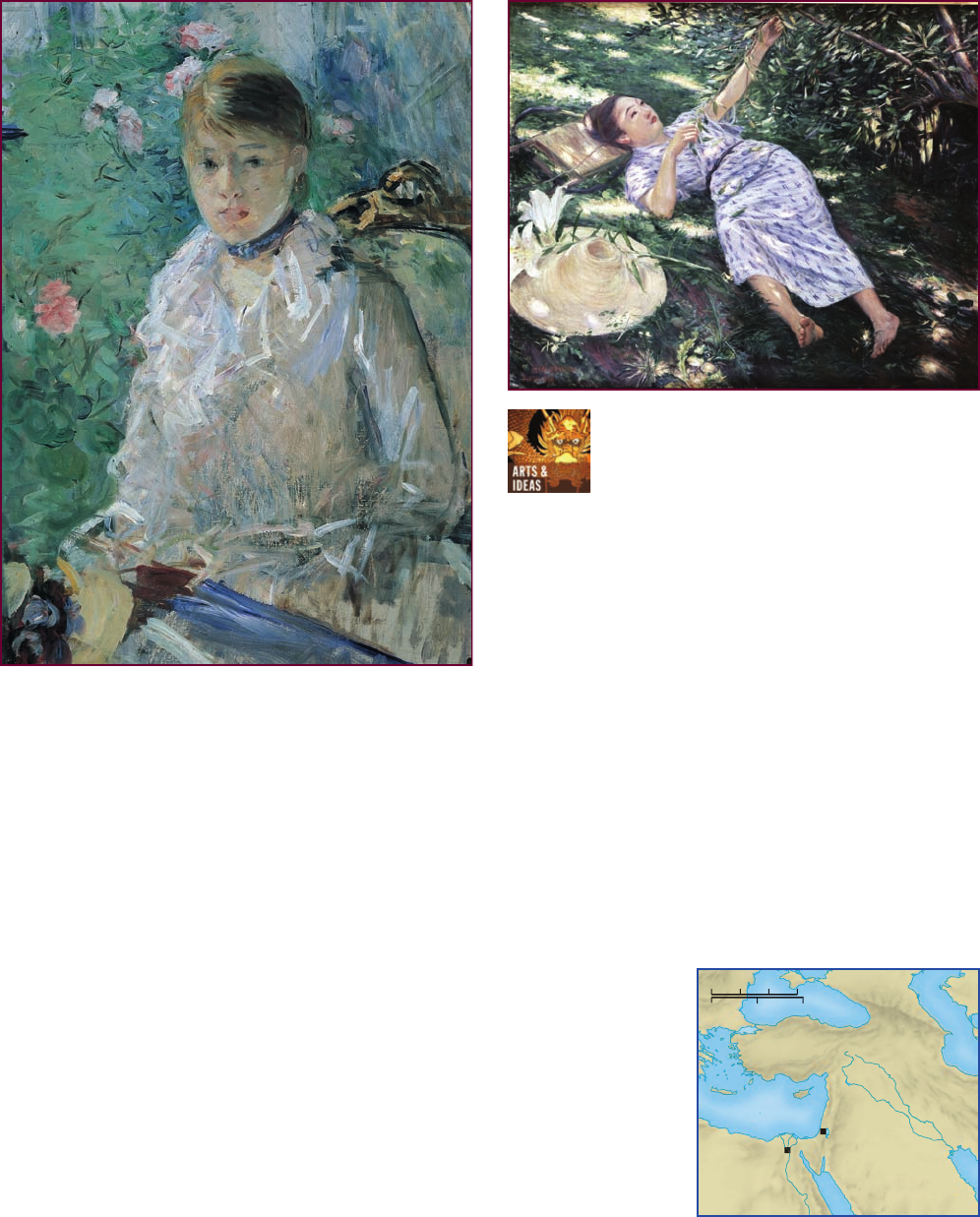

Painting— West and East. Berthe Morisot, the

first female painter to join the Impressionists,

developed her own unique style. Her gentle colors and

strong use of pastels are especially evident in Young Girl by the

Window, seen at the left. The French Impressionist style also spread

abroad. One of the most outstanding Japanese artists of the time

was Kuroda Seiki (1866–1924), who returned from nine years in

Paris to open a Western-style school of painting in Tokyo. Shown at

the right is his Under the Trees, an excellent example of the fusion

of contemporary French Impressionist painting with the Japanese

tradition of courtesan prints.

Q

What differences and similarities do you notice in these two

paintings?

c

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

c

Christie’s Images/SuperStock

A

r

ab

ia

n

Peninsula

M

e

M

M

d

i

t

e

r

r

a

r

r

n

e

a

n

S

e

a

Red

R

R

Sea

Cas

pia

n S

ea

Jer

Jer

Jer

er

usa

usa

usa

lem

l

lem

lem

C

air

o

EGY

PT

PT

PER

S

I

A

HEJA

Z

SYRIA

A

O

T

T

O

M

A

N

E

E

M

M

M

P

P

I

I

R

R

E

E

PALE

STINE

0

25

2

25

5

0

0

0

00500

500

500

50

50

0

0

500

5

0

0

0

0

Mi

Mi

Mi

M

l

les

les

500

50

500

50

500

500

500

500

0

0 2

50

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

5050

0

0

0

0

75

75 75

7

75

75

75

75

75

75

75

75

7

75

0K

0K

0 K

0 K

0K

0K

0K

0K

0K

0K

0K

0K

0K

0K

0K

0K

0

i

i

i

ilo

i

il

ii

i

i

i

i

i

i

met

ers

0

00

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

7757575

75

75

75

7

0K

0K

0 K

0K

0 K

0K

0 K

0K

0K

0

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

i

i

i

i

i

i

ii

i

0

5

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Palestine

TOWAR D T HE MODERN CONSCIOUSNESS:INTELLECTUAL AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS 509

long been the land of their dreams. Settlement in P alestine was

difficult, however, because it was then part of the Ottoman

Empire, which was opposed to Jewish immigration. Despite

the problems, the First Zionist Congress, which met in Swit-

zerland in 1897, proclaimed as its aim the creation of a ‘‘home

in Palestine secured by public la w’’ for the Jewish people. In

1900, around a thousand Jews migrated to Palestine, and the

trickle rose to about three thousand a year between 1904 and

1914, keeping the Zionist dream alive.

The Culture of Modernity

The revolution in physics and psychology was paralleled

by a revolution in literature and the arts. Before 1914,

writers and artists were rebelling against the traditional

literary and artistic styles that had dominated European

cultural life since the Renaissance. The changes that they

produced have since been called Modernism.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a group of

writers known as the Symbolists caused a literary revo-

lution. Primarily interested in writing poetry and strongly

influenced by the ideas of Freud, the Symbolists believed

that an objective knowledge of the world was impossible.

The external world was not real but only a collection of

symbols that reflected the true reality of the individual

human mind.

Theperiodfrom1870to1914wasoneofthemost

fertile in the history of art. By the late nineteenth century,

artists were seeking new forms of expression. The preamble

to modern painting can be found in Impressionism,

a movement that originated in France in the 1870s

when a group of artists rejected the studios and museums

and went out into the countryside to paint nature

directly.

An important Impressionist painter was Berthe M o-

risot (1841--1895), who believed that women had a special

vision that she described as ‘‘more delicate than that of

men.’’ She made use of lighter colors and flowing brush-

strok es (see the comparative illustration on p. 509). Near

the end of her life, she lamented the refusal of men to take

her work seriously: ‘‘I don ’t think there has ever been a

man who treated a woman as an equal, and that’s all I

would have asked, for I know I’m worth as much as they.’’

8

In the 1880s, a new movement known as Post-

Impressionism arose in France and soon spread to other

European countries. A famous Post-Impressionist was the

tortured and tragic figure Vincent van Gogh (1853--

1890). For van Gogh, art was a spiritual experience. He

was especially interested in color and believed that it

could act as its own form of language.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the belief

that the task of art was to represent ‘‘reality’’ had lost

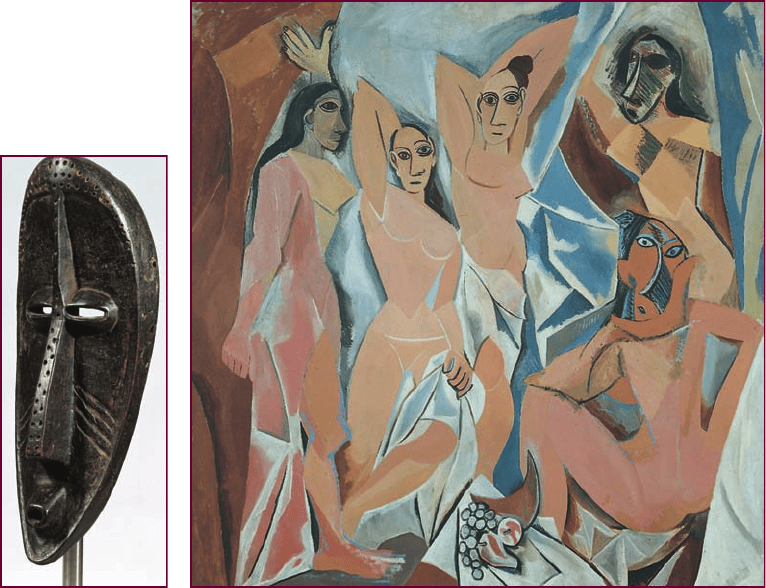

Pablo P icasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon .

Pablo Picasso, a major pioneer and activist of modern art,

experimented with a remarkable variety of modern styles. Les

Demoiselles d’Avignon was the first great example of Cubism,

which one art historian called ‘‘the first style of this [twentieth]

century to break radically with the past.’’ Geometrical shapes

replace traditional forms, forcing the viewer to re-create reality

in his or her own mind. The

head at the upper right of the

painting reflects Picasso’s

attraction to aspects of African

art, as is evident from the

mask included at the left.

c

2008 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Digital Image

c

The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by Scala/Art Resource, NY

c

Dr. Werner Muensterberger Collection/ The Bridgeman Art Library

510 CHAPTER 20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

much of its meaning. The growth of photography gave

artists one reas on to reject Realism. Invented in the

1830s, photography became popular and widespread

after 1888 when George Eastman created the first Kodak

camera for the mass market. What was the point of an

artist’s doing what the camera did better? Unlike the

camera, which could only mirror reality, artists could

create reality.

By 1905, one of the most important figures in

modern art was just beginning his career. Pablo Picasso

(1881--1973) was from Spain but settled in Paris in 1904.

Picasso was extremely flexible and painted in a

remarkable variety of styles. He was instrumental in the

development of a new style called Cubism that used

geometrical designs as visual stimuli to re-create reality in

the v iewer’s mind.

The modern artist’s flight from ‘‘visual reality’’

reached a high point in 1910 with the beginning of

abstract painting. A Russian who worked in Germany,

Vasily Kandinsky (1866--1944) was one of its founders.

Kandinsky sought to avoid representation altogether. He

believed that art should speak directly to the soul. To do

so, it must avoid any reference to visual reality and

concentrate on line and color.

CONCLUSION

FROM THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY, much of the Western

Hemisphere was under the control of Great Britain, Spain, and

Portugal. But between 1776 and 1826, an age of revolution in the

Atlantic world led to the creation of the United States and nine new

nations in Latin America. Canada and other new nations in Latin

America followed in the course of the nineteenth century. This age

of revolution was an expression of the force of nationalism, which

had first emerged as a political ideology at the end of the eighteenth

century. Influential, too, were the ideas of the Enlightenment that

had made an impact on intellectuals and political leaders in both

North and South America.

The new nations that emerged in the Western Hemisphere did

not, however, develop without challenges to their national unity.

Latin American nations often found it difficult to establish stable

TIMELINE

1800

1830 1860 1890 1920

Bolívar and San Martín lead

Latin America’s independence movements

The Americas

The United States

and Canada

Europe

Election of Andrew Jackson

Romanticism

Brazil gains independence from Portugal

Rule of Porfirio Diaz in Mexico

Mexican Revolution begins

Formation of the Dominion of Canada

Spanish-American War

Presidency of

Woodrow Wilson

American Civil War

Realism

Impressionism

Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

Einstein’s special theory

of relativity

Beginning of

abstract painting

CONCLUSION 511

SUGGESTED READING

Latin America For general surveys of Latin American history,

see M. C. Eakin, The History of Latin America: Collision of Cultures

(New York, 2007); P. Bakewell, A History of Latin A merica (Oxford,

1997); and E. B. Burns and J. A. Charlip, Latin America: An

Interpretive History , 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J ., 2007). For a

brief history, see J. C. Chasteen, Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise

History of Latin America, 2nd ed. (New York, 2005). A standard work

on the wars for independence is J. L ynch, The Spanish American

Revolutions, 1808--1826, 2nd ed. (New York, 1986); but also see J. C.

Chasteen, Americanos: Latin America ’s Struggle for Independence

(Oxford, 2008). On the nineteenth century, see S. F. Voss, Latin

A merica in the Middle Period, 1750--1920 (W ilmington, Del., 2002).

The Mexican Revolution is covered in M. J. Gonzales, The Mexican

Revolution, 1910--1940 (Albuquerque, N.M., 2002).

The United States and Canada On the United States in the

first half of the nineteenth century, see D. W . Howe, What God Hath

Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815--1848 (Oxford,

2007). The definitive one-volume history of the American Civil War is

J. M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era in the

Oxford History of the United States series (New York, 2003). On the

second half of the nineteenth century, see L. Gould, America in the

Progressive Era, 1890--1914 (New York, 2001). For a general history

of Canada, see S. W. See, History of Canada (Westport, N.Y., 2001).

The Emergence of Mass Society in the West An interesting

work on aristocratic life is D. Cannadine, The Decline and Fall of

the British Aristocracy (New Haven, Conn., 1990). On the middle

classes, see P. Pilbeam, The Middle Classes in Europe, 1789--1914

(Basingstoke, England, 1990). On the working classes, see

L. Berlanstein, The Working People of Paris, 1871--1914

(Baltimore, 1984). The rise of feminism is examined in J. Rendall,

The Origins of Modern Feminism: Women in Britain, France and

the United States (London, 1985).

Romanticism and Realism For an introduction to the

intellectual changes of the nineteenth century, see O. Chadwick,

The Secularization of the European Mind in the Nineteenth

Century (Cambridge, 1975). On the ideas of the Romantics, see

M. Cranston, The Romantic Movement (Oxford, 1994). For an

introduction to the arts, see W. Vaughan, Romanticism and Art

(New York, 1994), and I. Ciseri, Romanticism, 1780--1860: The

Birth of a New Sensibility (New York, 2003). A detailed biography

of Darwin can be found in J. Bowlby, Charles Darwin: A

Biography (London, 1990). On Realism, J. Malpas, Realism

(Cambridge, 1997), is a good introduction.

Toward the Modern Consciousness: Intellectual and

Cultural Developments

Two well-regarded studies of Freud are

P. D. Kramer, Sigmund Freud: Inventor of the Modern Mind (New

York, 2006), and P. Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (New York,

1988). Modern anti-Semitism is covered in A. S. Lindemann,

Esau’s Tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews

(New York, 1997). Very valuable on modern art are G. Crepaldi,

The Impressionists (New York, 2002), and B. Denvir, Post-

Impressionism (New York, 1992).

republics and resorted to strong leaders who used military force to

govern. And although Latin American nations had achieved

political independence, they found themselves economically

dependent on Great Britain as well as their northern neighbor, the

United States. The North American states had problems with

national unity, too. The United States dissolved into four years of

bloody civil war before reconciling, and Canada achieved only

questionable unity owing to distrust between the English-speaking

majority and the French-speaking minority.

By the second half of the nineteenth century, much of the

Western world was experiencing a new mass society in which the

lower classes in particular benefited from the right to vote, a higher

standard of living, and new schools that provided them with some

education. New forms of mass transportation, combined with new

work patterns, enabled large numbers of people to enjoy weekend

trips to ‘‘amusement’’ parks and seaside resorts, as well as to

participate in new mass leisure activities.

By the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the

twentieth century, a brilliant minority of intellectuals had created a

modern consciousness in the West that questioned most Europeans’

optimistic faith in reason, the rational structure of nature, and the

certainty of progress. This cultural revolution also produced anxiety

and created a degree of uncertainty that paralleled the anxiety and

uncertainty generated by the European national rivalries that had

grown stronger as a result of imperialistic expansion. At the same

time, the Western condescending treatment of non-Western

peoples, which we w ill examine in the next two chapters, caused

educated, non-Western elites in these colonies to initiate move-

ments for national independence. Before these movements could be

successful, however, the power that Europeans had achieved

through their mass armies and technological superiority had to be

weakened. The Europeans soon inadvertently accomplished this

task for their colonial subjects by demolishing their own civilization

on the battlegrounds of World War I.

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

512 CHAPTER 20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

513

CHAPTER 21

THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

The Spread of Colonial Rule

Q

What were the causes of the new imperialism of the

nineteenth century, and how did it differ from European

expansion in earlier periods?

The Colonial System

Q

What ty pes of administrative systems did the various

colonial powers establish in their colonies, and how

did these systems reflect the general philosophy of

colonialism?

India Under the British Raj

Q

What were some of the major consequences of British

rule in India, and how did they affect the Indian people?

Colonial Regimes in Southeast Asia

Q

Which Western countries were most active in seeking

colonial possessions in Southeast Asia, and what were

their motives in doing so?

Empire Building in Africa

Q

What facto rs were behind the ‘‘scramble for Africa,’’ and

what impact did it have on the continent?

The Emergence of Anticolonialism

Q

How did the subject peoples respond to colonialism,

and what role did nationalism play in their response?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

What were the consequences of the new imperialism

of the nineteenth century for the colonies and the

colonial powers? How do you feel the imperialist

countries should be evaluated in terms of their moti ves

and stated objectives?

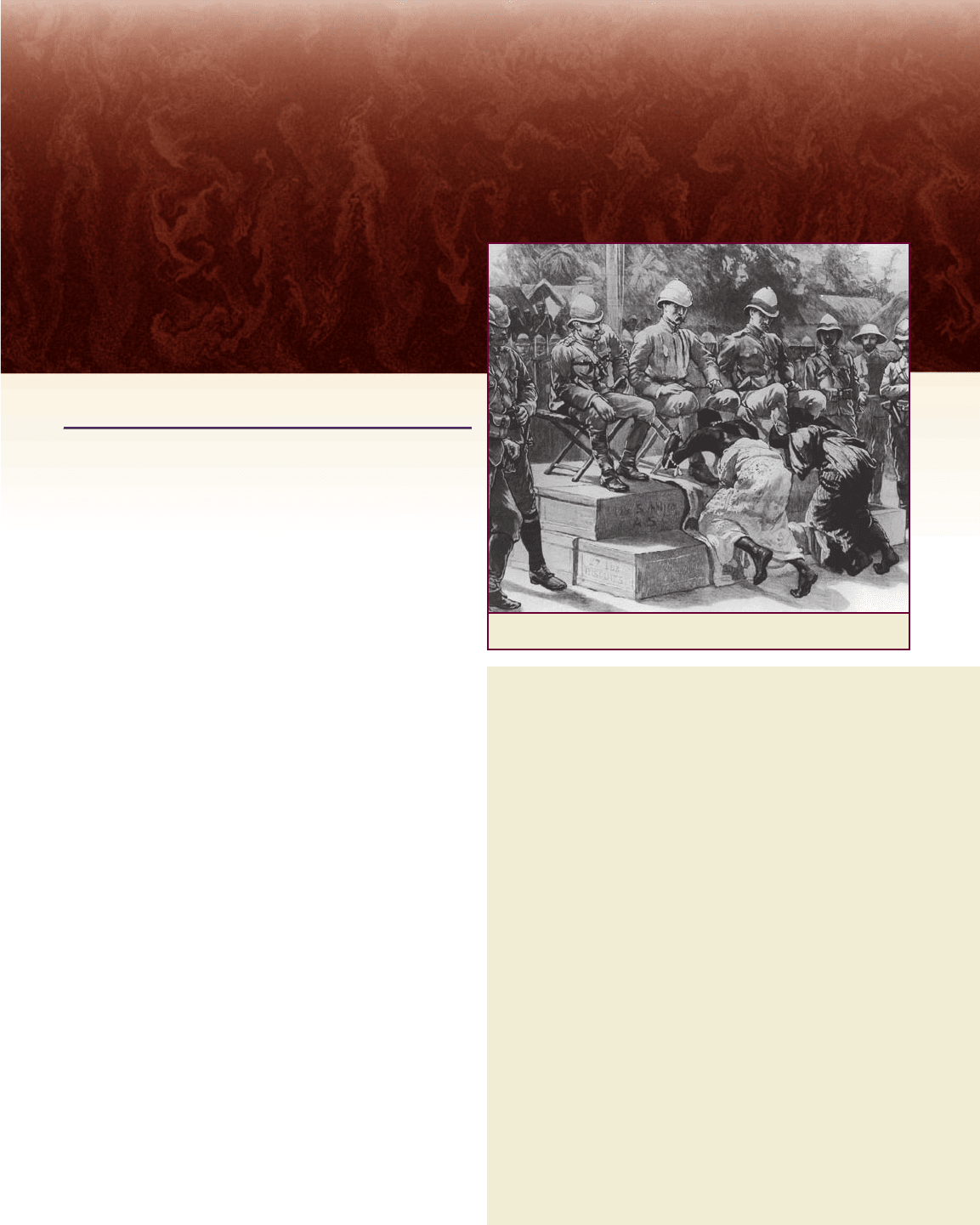

Revere the conquering heroes: Establishing British rule in Africa

c

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

514

IN 1877, THE YOUNG British empire builder Cecil Rhodes

drew up his last will and testament. He bequeathed his fortune,

achieved as a diamond magnate in South Africa, to two of his close

friends and acquaintances. He also instructed them to use the inher-

itance to form a secret society with the aim of bringing about ‘‘the

extension of British rule throughout the world, the perfecting of a

system of emigration from the United Kingdom ...especially the

occupation by British settlers of the entire continent of Africa, the

Holy Land, the valley of the Euphrates, the Islands of Cyprus and

Candia [Crete], the whole of South America. ... The ultimate recov-

ery of the United States of America as an integral part of the British

Empire ...then finally the foundation of so great a power as to

hereafter render wars impossible and promote the best interests of

humanity.’’

1

Preposterous as such ideas sound today, they serve as a graphic

reminder of the hubris that characterized the worldview of Rhodes

and many of his contemporaries during the age of imperialism, as

well as the complex union of moral concern and vaulting ambition

that motivated their actions on the world stage.

Through their efforts, Western colonialism spread throughout

much of the non-Western world during the nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries. Spurred by the demands of the Industrial

The Spread of Colonial Rule

Q

Focus Question: What were the causes of the new

imperialism of the nineteenth century, and how did it

differ from European expansion in earlier periods?

In the nineteenth century, a new phase of Western ex-

pansion into Asia and Africa began. Whereas European

aims in the East before 1800 could be summed up in

Vasco da Gama’s famous phrase ‘‘Christians and spices,’’

now a new relationship took shape as European nations

began to view Asian and African societies as sources of

industrial raw materials and as markets for Western

manufactured goods. No longer were Western gold and

silver exchanged for cloves, pepper, tea, silk, and porce-

lain. Now the prodigious output of European factories

was sent to Africa and Asia in return for oil, tin, rubber,

and the other resources needed to fuel the Western

industrial machine.

The Motives

The reason for this change, of course, was the Industrial

Revolution. Now industrializing countries in the West

needed vital raw materials that were not available at home,

as well as a reliable market for the goods produced in their

factories. The latter factor became increasingly crucial as

producers began to disco v er that their home markets

could not always absorb domestic output and that they

had to export their manufactures to make a profit.

As Western economic expansion into Asia and Africa

gathered strength during the nineteenth century, it be-

came fashionable to call the process imperialism. Al-

though the term imperialism has many meanings, in this

instance it referred to the efforts of capitalist states in the

West to seize markets, cheap raw materials, and lucrative

avenues for investment in the countries beyond Western

civilization. In this interpretation, the primary motives

behind the Western expansion were economic. Promoters

of this view maintained that modern imperialism was a

direct consequence of the modern industrial economy.

As in the earlier phase of Western expansion, how-

ever, the issue was not simply an economic one. Eco-

nomic concerns were inevitably tinged with political

overtones and with questions of national grandeur and

moral purpose as well. In the minds of nineteenth-

century Europeans, economic wealth, national status, and

political power went hand in hand with the possession of

a colonial empire. To global strategists, colonies brought

tangible benefits in the world of balance-of-power politics

as well as economic profits, and many nations became

involved in the pursuit of colonies as much to gain

advantage over their rivals as to acquire territory for its

own sake.

The relationship between colonialism and national

survival was expressed directly in a speech by the French

politician Jules Ferry in 1885. A policy of ‘‘containment or

abstinence,’’ he warned, would set France on ‘‘the broad

road to decadence’’ and initiate its decline into a ‘‘third-

or fourth-rate power.’’ British imperialists, convinced by

the theory of social Darwinism that in the struggle be-

tween nations, only the fit are victorious and survive,

agreed. As the British professor of mathematics Karl

Pearson argued in 1900, ‘‘The path of progress is strewn

with the wrecks of nations; traces are everywhere to be

seen of the [slaughtered remains] of inferior races. ... Ye t

these dead people are, in very truth, the stepping stones

on which mankind has arisen to the higher intellectual

and deeper emotional life of today.’’

2

For some, colonialism had a moral purpose, whether

to promote Christianity or to build a better world. The

British colonial official Henry Curzon declared that the

British Empire ‘‘was under Providence, the greatest in-

strument for good that the world has seen.’’ To Cecil

Rhodes, the most famous empire builder of his day, the

extraction of material wealth from the colonies was only a

secondary matter. ‘‘My ruling purpose,’’ he remarked, ‘‘is

the extension of the British Empire.’’

3

That British Em-

pire, on which, as the saying went, ‘‘the sun never set,’’

was the envy of its rivals and was viewed as the primary

source of British global dominance during the second half

of the nineteenth century.

The Tactics

With the change in European motives for colonization

came a corresponding shift in tactics. Earlier, when their

economic interests were more limited, European states

had generally been satisfied to deal with existing inde-

pendent states rather than attempting to establish direct

control over vast territories. There had been exceptions

where state power at the local level was at the point of

collapse (as in India), where European economic interests

were especially intense (as in Latin America and the East

THE SPREAD OF COLONIAL RULE 515

Revolution, a few powerful Western states---notably, Great Britain,

France, Germany, Russia, and the United States---competed ava-

riciously for consumer markets and raw materials for their expand-

ing economies. By the end of the nineteenth century, virtually all of

the traditional societies in Asia and Africa were under direct or indi-

rect colonial rule. As the new century began, the Western imprint on

Asian and African societies, for better or for worse, appeared to be a

permanent feature of the political and cultural landscape.