Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

481

Carolina admitted that he did not expect an organized disturbance, although he

coupled this denial with a request that federal troops “be vigilant and watchful

keeping the negroes in perfect order and arresting every one of them who may be

turbulent or drunk.”

54

Warnings from Southern whites became more frantic as the holidays neared.

The sheriff of St. Helena Parish, on the Louisiana-Mississippi state line, claimed

in a Christmas Eve telegram to have “information from white & black persons that

the negro troops at Baton Rouge intend to come out to the country for insurrection-

ary purposes on Christmas.” The commanding ofcer of the 47th USCI, at the state

capital, dismissed the report as having “no shadow of foundation.” In the end, the

season passed quietly throughout the South.

55

Although the rumors of insurrection arose from white peoples’ generations-old

fear of slave rebellions as much as from the novel sights of black men in uniform

patrolling towns and former slaves associating freely, some white observers had

predicted an uprising when black Southerners’ hopes of land redistribution col-

lapsed after the war. In fact, expectations of free land were as widespread among

black Southerners as fears of an uprising were among whites. Andrew Johnson

himself, in a speech to black Tennesseans during the presidential campaign of

1864, had hinted at postwar conscation of large estates and their division among

“loyal, industrious farmers.” In early September 1865, during the days between the

muster-out of the 55th Massachusetts at Charleston, South Carolina, and its voy-

age to Boston for nal payment and discharge, Capt. Charles C. Soule, at his com-

manding ofcer’s insistence, sent a letter to General Howard that addressed the

subject. During that brief period, when the regiment was out of service but ofcers

and men had not entirely become civilians, Soule and his colonel thought that “one

or two subjects may be addressed, upon which an ofcer in the army could hardly

touch with propriety.” Among these was black Carolinians’ idea “that all the land

is to be partitioned out to them in January.” “In this belief they have been encour-

aged by some of the colored troops,” Soule told Howard. “Even if justice is had in

the division of the crops [between laborers and landowners], which cannot in every

case be expected, they will be disappointed and dissatised at . . . getting none of

the stock or other property upon the farms. There is a discontented and riotous feel-

ing among them, which must culminate at some time or other, and this feeling is

not directed against their former masters alone, but also, in some instances, against

the United States forces.” Early that summer, when ofcers of the 55th Massachu-

setts and other regiments had visited plantations near Orangeburg to impress on the

freedpeople the necessity for labor contracts with their former masters, “the idea

. . . gained universal currency among the negroes, . . . that these envoys were not

54

Col F. M. Crandal to Maj Gen J. P. Hawkins, 30 Oct 1865 (H–300–DL–1865), Entry 1757, pt.

1, RG 393, NA; Maj A. T. Reeve to Maj Gen C. B. Fisk, 23 Dec 1865 (F–231–MDT–1865), Entry

926, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; 2d Lt J. G. Hort to Capt H. James, 30 Nov 1865, NA Microlm Pub M1909,

Rcds of the Field Ofces for the State of North Carolina, BRFAL, roll 35; Col [sic] E. Whittlesey to

Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 8 Dec 1865, NA M752, roll 23; Orr to Sickles, 13 Dec 1865 (“be vigilant”);

Hahn et al., Land and Labor, pp. 131–33 (North Carolina), 834–40 (Arkansas); Gad Heuman, “The

Killing Time”: The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press,

1994).

55

J. W. Dodd to Capt E. R. Ames, 24 Dec 1865 (D–191–DL–1865), and Col H. Scoeld to

“Lieut Wood,” 26 Dec 1865 (L–885–DL–1865), both in Entry 1757, pt. 1, RG 393, NA.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

482

United States ofcers, but planters in disguise,” trying “to cajole them into ‘signing

away their freedom.’”

56

Some observers attributed the freedpeople’s faith in imminent land redistribu-

tion to tales spread by black soldiers, but Soule blamed “Sherman’s men,” who

had traversed the Carolinas early in the year. When white ofcers brought dif-

ferent news, he wrote, black residents refused to believe “so unpalatable an an-

nouncement,” so the regiment sent parties of “intelligent and judicious” enlisted

men instead to set up camps, transmit information, and preserve order throughout

the Orangeburg District. “The system worked much better than anticipated,” Soule

told Howard. By November, the 35th USCI had fteen enlisted men “visiting plan-

tations” more than ninety miles east of Orangeburg, the commanding ofcer wrote.

The squad reported to regimental headquarters at Georgetown on Saturdays, re-

ceived instructions for the coming week, and set off again on its rounds.

57

Sherman’s soldiers could not have been solely responsible for the idea of a

massive redistribution of farmland, of course. The belief was widespread across

the South. A more plausible source was the conversation of slaveholders them-

selves, as they urged each other to greater wartime effort with assertions that Yan-

kee abolitionists were hell-bent on freeing their slaves and dividing the plantations

among them. Overhearing a rant like this, house servants carried the news to the

slave quarters, where it gained wide circulation. This was the explanation that Gen-

eral Saxton, who had longer experience with freedpeople than anyone in the Army,

offered to General Howard.

58

Desire for land ownership was universal among rural black Southerners. “They

ask ‘what is the value of freedom if one has nothing to go on?’ That is to say, if

property in some shape or other is not to be given us, we might as well be slaves,”

Chaplain Thomas Smith of the 53d USCI reported from Jackson, Mississippi.

“Nearly all of them have heard, that at Christmas, Government is going to take the

planters’ lands and other property . . . and give it to the colored people,” the chap-

lain continued. As a result, few freedmen were willing to sign a labor contract for

the coming year. The South Carolina Sea Islands formed part of the coastal tract

that General Sherman had reserved for black settlement in January 1865. Nearly

a year later, white landowners with presidential pardons were returning to reclaim

their plantations. “The [freedmen] are exceedingly anxious to buy or lease land,

rather than to hire themselves to their former owners. They . . . will gladly pay any

56

Capt C. C. Soule to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, [8 Sep 1865], NA M752, roll 17; Johnson Papers,

7: 251 (“loyal, industrious”); Hahn et al., Land and Labor, pp. 814–16, 856; Eugene D. Genovese,

Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Pantheon Books, 1974), pp. 588–89,

592–96. The 35th USCI detailed three ofcers as a “Special Commission for Making Contracts.”

35th USCI, SO 40, 20 Jun 1865, 35th USCI, Regimental Books, RG 94, NA.

57

Soule to Howard, [8 Sep 1865]. General Howard’s brother also thought the freedmen’s ideas

of land redistribution came from Sherman’s army. Brig Gen C. H. Howard to Maj Gen R. Saxton, 17

Nov 1865, and Maj A. J. Willard to Maj W. H. Smith, 13 Nov 1865 (quotation), both in NA M869,

roll 34; Maj A. J. Willard to Capt G. W. Hooker, 19 Nov 1865, Entry 4112, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Hahn

et al., Land and Labor, p. 381; Foner, Reconstruction, p. 68.

58

Maj Gen R. Saxton to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 6 Dec 1865, NA M752, roll 24. A letter from

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton assigned Saxton to manage plantations on the South Carolina

Sea Islands in April 1862. OR, ser. 3, 2: 27–28. See also Steven Hahn, A Nation Under Our Feet:

Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration (Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 2003), pp. 130–31.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

483

reasonable or unreasonable price for it,” Brig. Gen. James C. Beecher reported

from Edisto Island, “but if they must give up the land they will do it peaceably. A

large number . . . will go to the main land preferring to hire out there” rather than

work for their former masters, “if they must hire out at all.” Capt. William L. Cadle

of the 6th USCA reported in December that freedmen in southern Mississippi were

“still hopeful that something will turn up about Christmas that will be to their in-

terest.” Yet Christmas came and went without realizing the hopes or fears of either

black or white Southerners, and in January freedmen began making contracts to

work during the coming year.

59

With incidents of assault and murder occurring every day and rumors of an

impending uprising by freedmen circulating widely, it is not surprising that tales of

other conspiracies reached federal ofcers. In September, the general commanding

at Mobile reported hearing from the governor of Alabama and the Freedmen’s Bu-

reau assistant commissioner for the state that white men north of the city were lur-

ing freedmen to the Florida coast with promises of work, then taking them aboard

ship to Cuba, where slavery still thrived, and selling them to sugar planters. The

general’s report resulted in months of investigation by ofcers of the 34th and 82d

USCIs, who reported no evidence of any “cargo of negroes” going to Cuba. The

Cuban slave ships proved to be as insubstantial as the freedmen’s uprising.

60

While the military occupation of the South wore on through the fall of 1865,

Northerners turned increasingly worried eyes on political developments in the re-

gion. On 20 November, the new, popularly elected governor of Mississippi told the

state legislature: “Under the pressure of Federal bayonets, . . . the people of Mis-

sissippi have abolished the institution of slavery. . . . The negro is free, whether we

like it or not. . . . To be free, however, does not make him a citizen, or entitle him

to political or social equality with the white man.” He then recommended several

laws intended “for the protection and security . . . of the freedmen . . . against evils

that may arise from their sudden emancipation.” One law would declare the testi-

mony of black witnesses admissible in court; another would establish a state mili-

tia; a third law or set of laws would “encourage” black workers “to enter in some

pursuit of industry . . . and then, with an iron will and the strong hand of power,

take hold of the idler and the vagrant and force [them] to some protable employ-

ment.” By passing these laws, the governor assured the legislators, “we may secure

the withdrawal of the Federal troops.”

61

As news of this and other developments in the South appeared in Northern

newspapers, discharged Union veterans of both political parties and their families

began to join Radical Republicans and abolitionists in wondering whether their

four years of striving and sacrice had been in vain. “Has the South any statesmen

59

Chaplain T. Smith to Capt J. H. Weber, 3 Nov 1865 (M–82), NA M752, roll 22; Brig Gen J. C.

Beecher to Capt T. D. Hodges, 2 Dec 1865, Entry 4112, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Capt W. L. Cadle to Maj

G. D. Reynolds, 10 Dec 1865, NA M1907, roll 32.

60

Maj Gen C. R. Woods to Brig Gen W. D. Whipple, 20 Sep 1865 (A–455–MDT–1865), Entry

926, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Maj Gen J. J. Foster to Col G. L. Hartsuff, 6 Mar 1866 (G–186–AGO–1866)

(quotation), and 1st Lt D. M. Hammond to 1st Lt J. M. J. Sanno, 18 Feb 1866, both in NA M619, roll

473; Capt G. H. Maynard to Maj Gen J. G. Foster, 25 Apr 1866 (f/w G–295–AGO–1866), NA M619,

roll 474.

61

Governor’s message quoted in New York Times, 3 December 1865; Foner, Reconstruction,

pp. 224–25.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

484

still living?” an editorialist at the Republican New York Tribune wondered. Af-

ter citing alarming developments in Mississippi, Florida, and South Carolina, the

writer concluded that other Southern states would enact similar laws in an effort to

be rid of federal troops. “The incessant and general outcry against Negro Soldiers

forebodes this. . . . The Government is now pressed by the ex-Rebels to disband

its Black soldiers forthwith. It is doing so as fast as it can. But what is to become

of these soldiers? Many if not most of them dare not return to the homes they left

to enter the Union service. They know they would be hunted down and killed by

their badly reconstructed White neighbors.” These white neighbors, a Philadelphia

Inquirer editorial said, were “slow to learn. Our Southern brethren evidently need

much instruction. . . . They have suffered some humiliation, but it is evident that

they will be required to endure much more before they can understand exactly

the situation which they occupy.” Even the New York Times, a staunch supporter

of President Johnson and his policies, called results of the recent elections in the

South “unsatisfactory.”

62

The Times pronounced its judgment as members of the Thirty-ninth Congress

gathered in Washington. All of the representatives and one-third of the senators

had been elected the previous year, during the last autumn of the war. All came

from states that had stayed in the Union. They numbered 176 Republicans, 49

Democrats, and 22 Unionists from the border states and Tennessee. Since it is the

prerogative of Congress to review the credentials of its members, the rst order of

business was to decide whether to seat the twenty senators and fty-six representa-

tives recently elected in the ten occupied states. One of Georgia’s senate choices

was Alexander H. Stephens, who eight months earlier had been vice president of

the Confederacy; ten of the other prospective members had served as generals in

the Confederate Army. On the rst day of the session, Thaddeus Stevens, the lead-

ing Radical Republican in the House, moved that seating the Southerners be post-

poned until a joint committee had investigated “the condition of the States which

formed the so-called Confederate States of America, and report[ed] whether they,

or any of them are entitled to be represented in either house of Congress.” The legal

basis for the inquiry was the constitutional guarantee to each state of a republican

form of government. That Southern voters had elected so many candidates who

had played prominent parts in the rebellion proved to many Republicans that all

was not yet well in that part of the country.

63

The House approved Stevens’ motion by a vote of 133 to 36, with 13 absten-

tions; as did the Senate, 33 to 11. A committee of six senators and nine representa-

tives began examining witnesses in January and continued into May. It questioned

Union and Confederate leaders, among them Robert E. Lee and Alexander H.

Stephens; less prominent Union generals, some of whom had commanded black

troops during the war; General Saxton, who had supervised freedmen’s affairs for

years in the Department of the South; the adjutant general, Brig. Gen. Lorenzo

Thomas, who had organized black regiments in the Mississippi Valley in 1863; and

62

New York Tribune, 24 November 1865; Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 November 1865; New York

Times, 2 December 1865.

63

Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction . . . (Washington, D.C.: Government

Printing Ofce, 1866), pp. iii, ix; Foner, Reconstruction, pp. 196, 225–26.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

485

lesser soldiers and civilians, in person and by letter. Among those testifying were

recently discharged ofcers who had served with black regiments in most parts

of the South. Some were still serving there as agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

64

Committee members wanted to know how the withdrawal of federal troops

would affect public order in the South. Two former ofcers of the 101st USCI

expressed their views. Robert W. Barnard, the regiment’s colonel, said that an old

Unionist resident had told him, “If you take away the military from Tennessee,

the buzzards can’t eat up the niggers as fast as we’ll kill ’em.” John H. Cochrane,

the lieutenant colonel, agreed that in parts of the state, freedmen, northerners, and

southern Unionists would be in danger if federal troops left. George O. Sanderson,

who had served with the 1st USCI as a lieutenant in North Carolina, said that

without supervision, planters would reduce farmworkers’ wages to less than thirty-

eight cents a day, “to make it worse for them . . . than before they were freed.” Poor

whites, Sanderson said, “feel bitter towards the free class. . . . They say that they

will drive them out of the country; they will not . . . live side by side with them.”

From Mississippi, Capt. James H. Mathews, of the 66th USCI, serving as a Bureau

agent, contributed a letter that told how one soldier from his regiment had been

assaulted and run out of town during a visit to his home. The commanding ofcer

of the 113th USCI wrote from Arkansas that “if the troops should be withdrawn,

. . . civil government would be too weak to protect society, and terror and confusion

would be the result.”

65

For the most part, the statements of these and other witnesses divided sharply

along lines drawn during the war, with Unionists demanding further military occu-

pation and former secessionists denying the need for it. The division was the same

as the one the committee noted in the recent state elections, which “had resulted,

almost universally, in the defeat of candidates who had been true to the Union, and

in the election of notorious and unpardoned rebels, men who could not take the

prescribed oath of ofce and who made no secret of their hostility to the govern-

ment and the people of the United States.” The committee found that the conven-

tions summoned by provisional governors had made only the most supercial at-

tempts to reconstitute state government before calling elections. “Hardly is the war

closed,” the committee reported, “before the people of these insurrectionary States

come forward and haughtily claim, as a right, the privilege of participating at once

in that government which they had for four years been ghting to overthrow.”

66

While the committee heard testimony and wrote its report, Congress became

increasingly estranged from the president. In February, Johnson vetoed a bill that

would have extended the existence of the Freedmen’s Bureau for another year,

until early 1867. An effort to override that veto failed, but the president’s con-

duct continued to alienate moderate Republicans, who made up the bulk of the

party’s membership in Congress. In April, they contributed to the majority neces-

sary to override Johnson’s veto of a civil rights bill that guaranteed freedpeople

64

Lee’s testimony is in Report of the Joint Committee, pt. 2, pp. 129–36; Stephens’, in pt. 3, pp.

158–66; Saxton’s, in pt. 2, pp. 216–31, and pt. 3, pp. 100–102; Thomas’, in pt. 4, pp. 140–44. House

and Senate votes on Stevens’ motion are in Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess., pp. 6, 30.

65

Report of the Joint Committee, pt. 1, p. 121 (“If you”); pt. 2, pp. 175 (“to make it”), 176 (“feel

bitter”); pt. 3, pp. 146–47, 170 (“if the troops”).

66

Report of the Joint Committee, pp. x (quotation), xvi (“Hardly is”).

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

486

“full and equal . . . security of person and property as is enjoyed by white citizens.”

Three months after that, two-thirds of both houses passed a second version of the

Freedmen’s Bureau bill hours after another veto. The president’s vetoes and his

intemperate speeches attacking opponents in Congress, coupled with the actions of

white Southerners, had driven the moderate Republicans to ally with the Radicals,

creating a veto-proof majority in both houses.

67

As Congress and the president sparred in Washington, a dwindling number

of black regiments undertook an even greater share of occupation duties. On

11 December, the War Department issued an order to muster out all remain-

ing white volunteer regiments in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi, leaving

an occupying force of about seven thousand U.S. Colored Troops and white

regulars. Later that month, the Freedmen’s Bureau assistant commissioner for

Georgia, Brig. Gen. Davis Tillson, wrote to General Howard requesting direct

command of the remaining troops in the state, since “their duties will consist

almost wholly in aiding ofcers of the bureau.” In January, after the last white

volunteers had left, Tillson reported that Bureau ofcers in more than seven

67

Bentley, History of the Freedmen’s Bureau, pp. 115–20, 133–35; Foner, Reconstruction, pp.

243–51; Trefousse, Andrew Johnson, pp. 240–53. Text of the Civil Rights Bill is in McPherson,

Political History, pp. 78–80 (quotation, p. 78).

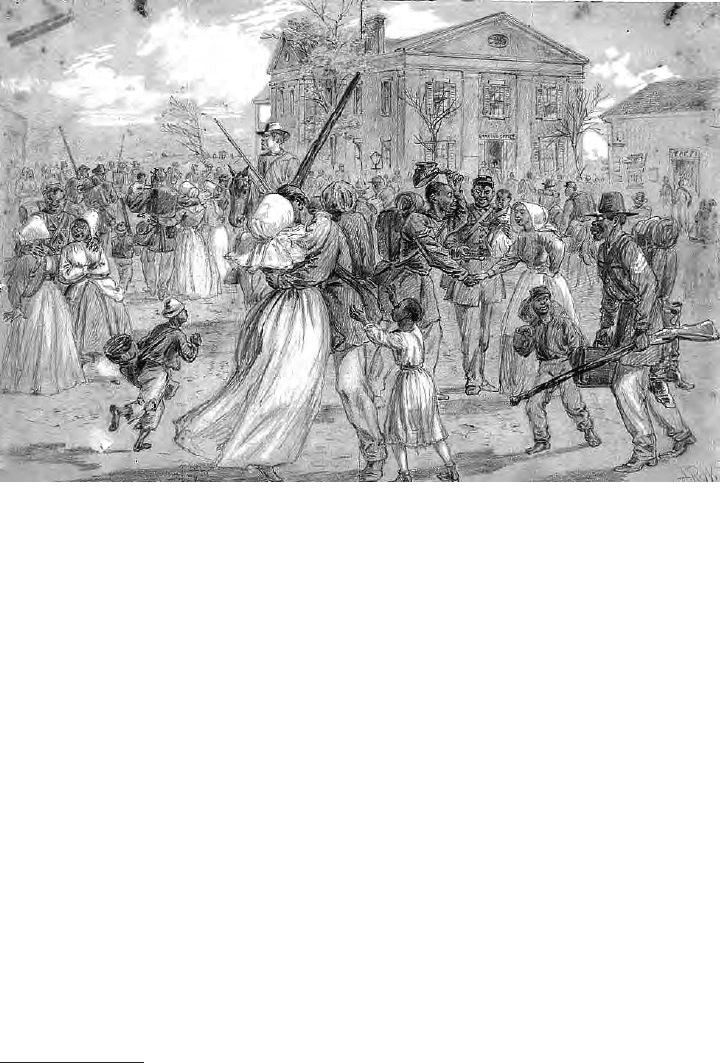

Black veterans were as eager to get out of uniform as most American soldiers have been

at the end of every war. Alfred R. Waud recorded this scene in Little Rock, where the

113th U.S. Colored Infantry mustered out in April 1866.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

487

towns sorely missed “the presence of at least a few troops,” and that agents

were “powerless without them.” “In almost every case, . . . the withdrawal of

troops has been followed by outrages upon the freed people,” he wrote. “A

large number of troops is not required, but . . . unless small garrisons are kept

at many points, most unfortunate results will certainly follow.” Tillson was

right: reports of murders in Georgia during 1866, although sketchy, indicate

a sevenfold increase after the 103d USCI mustered out in April, leaving only

eight companies of regular infantry in the state. A report from South Carolina

shows a similar, although less pronounced, trend after June, when the muster-

out of white volunteers there left the 128th USCI, thirteen companies of regu-

lar infantry, and two companies of regular cavalry as the occupying force in

the state. Although South Carolina was smaller than Georgia, its garrisons in-

cluded nearly 25 percent more federal troops. While white peace ofcers were

reluctant to arrest white murderers of black people and white juries refused

to convict them, the increase of reported murders in both states after troop

withdrawals suggests that even an occupation force of infantry served as some

deterrent to racial violence.

68

At the beginning of 1866, some sixty-ve thousand black soldiers were

still in service, representing slightly more than 53 percent of the remaining

Civil War volunteers. Two months later, after more white regiments mustered

out, the number of black troops had shrunk to fewer than forty thousand, but

their proportion of the force had grown to nearly 60 percent. By early summer,

only 17,320 black volunteers remained, constituting nearly three-quarters of

the men still in service who had volunteered “for three years or the war.” Shar-

ing their duties were companies of the Regular Army—more than 70 percent

of the regular infantry force, one regiment of cavalry, and one of artillery—but

some eighteen thousand regulars could hardly compensate for the mustering

out of nearly one hundred thousand volunteers, white and black, during the rst

six months of the year.

69

Despite pleas and protests from commanding ofcers and Freedmen’s Bureau

agents, troop numbers in the South continued to dwindle. General Beecher asked

for a company of his old regiment, the 35th USCI, to escort him while he settled

labor contracts near the South Carolina coast that winter. In Kentucky and Ten-

nessee, the assistant commissioner for those states told General Howard, troops

had become so scarce by spring that they “could do but little else than guard the

government property and garrison the chief cities.” The Bureau agent at Hamburg,

Arkansas, an ofcer of the 5th USCC, had to abandon his station until “troops suf-

cient to protect him from personal violence” could be sent there. In the southwest

corner of the state, a former ofcer of the 113th USCI acting as a Bureau agent

feared an armed conict. “The most direct cause is the colored troops stationed

here—the feeling is very bitter, and I daily look for a conict,” he reported. “It is

68

OR, ser. 3, 5: 13; “Freedmen’s Bureau,” p. 315 (“their duties”), p. 328 (“the presence”); Rpts

of Persons Murdered, Dists of Atlanta, Brunswick, Columbus, Grifn, Macon, Marietta, Rome,

Savannah, Thomasville, Entry 642, Georgia: Rpts of Murders and Outrages, RG 105, Rcds of the

BRFAL, NA; Rpt of Outrages, NA M869, roll 34.

69

OR, ser. 3, 5: 138–39, 932, 973; Army and Navy Journal, 28 July 1866.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

488

strongly threatened, and . . . the troops would all be killed . . . if I sent them out

to make any arrest. There are but 13 of them not enough to enforce respect to the

authority of the U.S. nor defend themselves if the conict comes. . . . Either white

troops should be sent here or enough colored ones to enable them to enforce order

& protect themselves.”

70

The effectiveness of the occupying force continued to decline through the

winter. Freedmen’s Bureau agents in Kentucky and Arkansas needed military

escorts to make arrests for murder and theft, and could not get them. Where

black infantry regiments were available, ofcers had requests of their own.

Post commanders at Grenada, Mississippi, and Baton Rouge asked for horses

enough to mount a few infantrymen. Without an escort, the commanding of-

cer of the 84th USCI explained, it was dangerous for a federal ofcial to travel

more than eight or ten miles outside the state capital of Louisiana. The Bu-

reau’s assistant commissioner for Arkansas asked the department commander

to send a company of cavalry to Hamburg, which he said was “controlled by

unsubdued rebels.” In the northern part of the state, an ofcer and two enlisted

men of the 113th USCI, the only mounted force available, tried to arrest a man

for assaulting a Bureau agent. They followed the assailant to his home, where

he shot at them and, since his three pursuers were not enough to cover all sides

of the house, rode off in the night. The Bureau agent at Duvall’s Bluff, an of-

cer of the same regiment, concluded that it was “almost impossible . . . to

enforce the regulations of the Bureau without troops.” Nevertheless, the War

Department continued to disband the volunteer force. Forty-one more black

regiments mustered out during the winter.

71

Events in Georgia during the rst postwar fall and winter illustrate the sort

of relations that prevailed between white planters, black farmworkers, de-

ant former Confederates, Freedmen’s Bureau agents, and soldiers in the ever-

dwindling occupation force. Maj. William Gray of the 1st USCA was a Bureau

inspector in the state. In counties northwest of Augusta, he found:

Many of the farmers have not yet settled with, and say they do not intend to pay,

the freed people for their last year’s work. The ignorance of the freed people

has been taken advantage of . . . , and many of the white people have coerced

them into making contracts at from $2 to $4 and $6 per month—stating that, if

they did not . . . go to work after New Year, they would all be taken away, sent

70

Brig Gen J. C. Beecher to Lt M. N. Rice, 9 Jan 1866 (f/w D–26), NA M752, roll 20; Maj Gen

C. B. Fisk to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 30 Apr 1866 (F–30–MDT–1866) (“could do”), Entry 926, pt. 1,

RG 393, NA; Capt E. G. Barker to Brig Gen J. W. Sprague, 28 Apr 1866 (S–66–DA–1866) (“troops

sufcient”), and A. W. Ballard to Col D. H. Williams, 30 Apr 1866 (B–10 [Sup] DA–1866) (“The

most”), Entry 269, pt. 1, RG 393, NA.

71

2d Lt R. W. Thing to 2d Lt J. T. Alden, 8 Jan 1866 (T–121), NA T142, roll 27; W. G. Bond to

Maj Gen C. B. Fisk, 23 Jan 1866 (B–26), NA T142, roll 28; Maj E. Boedicker to 1st Lt J. K. Wood,

12 Jan 1866 (B–26–DL–1866), Entry 1757, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Capt S. Marvin to Col M. P. Bestow,

10 Feb 1866 (S–25–DM–1866), Entry 2433, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Brig Gen J. W. Sprague to Maj Gen

J. J. Reynolds, 17 Jan 1866 (“controlled by”), NA M979, roll 1; Capt E. P. Gillpatrick to Maj J. M.

Bowler, 16 Jan 1866, NA M979, roll 6; 1st Lt W. S. McCullough to Capt D. H. Williams, 31 Jan 1866

(“almost impossible”), NA M979, roll 23.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

489

to Cuba, and sold into slavery. I spoke of this to the white people, and they did

not deny it.

Cheating farmworkers and lying to them were widespread practices in the

postwar South, but the Georgia planters, being unfamiliar with a free labor system,

had not reckoned on differences in the availability of labor, both within the state

and in the region as a whole. That fall, General Tillson foresaw great suffering in

the months to come and promised “immediate and vigorous efforts to provide all

freed people . . . with opportunities for labor where fair compensation and kind

treatment will be secured to them. This is the only practicable and comprehensive

plan of providing for their necessities.” By winter, recruiters from Arkansas, Mis-

sissippi, and Missouri had arrived in the state, offering twenty and even twenty-ve

dollars a month to workers who were willing to migrate.

72

By the rst week in December 1865, several hundred freedmen and their fami-

lies had signed up to work on plantations in Arkansas and Tennessee, but in a few

weeks, the ow slowed to a trickle. Farmworkers were “afraid, and justly so,” Ma-

jor Gray reported, “that, if they attempt to leave, they will be in danger of bodily

injury.” Among the agents of fear were bands of self-styled “regulators” that had

operated for months in the northeastern part of the state. Their members were “not

mere outlaws but sons of wealthy and inuential families,” Tillson told General

Howard. “They openly declare that no negro shall live upon land owned or rented

by himself, but that he shall live with some white man or leave the country.” West

of Augusta, farmworkers told another Freedmen’s Bureau ofcer in January 1866

“that the white people would not allow them to leave,” and local planters asserted

“that they have always had their labor and they intend to have it now and at their

own price.”

73

White Georgians threatened Freedmen’s Bureau ofcers as well as black farm-

hands. Before leaving Augusta on an inspection tour in January, Gray received

warning from a Bureau agent “that it would be unsafe for me to go . . . without pro-

tection and I found on my arrival . . . that this was a necessary precaution. . . . I felt

myself unsafe during my entire stay.” Arthur T. Reeve, former major of the 88th

USCI, met the inspector en route. Reeve’s regiment had been consolidated with the

3d USCA at Memphis a month earlier. He was no longer in the Army, but instead

72

Maj W. Gray to Maj Gen D. Tillson, 31 Jan 1866 (“many of”), NA Microlm Pub M798,

Rcds of the Asst Commissioner for the State of Georgia, BRFAL, roll 27; “Freedmen’s Bureau,”

39th Cong., 1st sess., H. Ex. Doc. 70, p. 57 (“immediate and”); Maj W. Gray to W. M. Haslett, 22

Jan 1866, NA M798, roll 1; Cimbala, Under the Guardianship, p. 148. For instances of cheating

farmworkers, see Roberta S. Alexander, North Carolina Faces the Freedman: Race Relations

During Presidential Reconstruction, 1865–67 (Durham: Duke University Press, 1985), pp. 101–02;

James T. Currie, Enclave: Vicksburg and Her Plantations (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi,

1980), p. 156; Robert T. McKenzie, One South or Many? Plantation Belt and Upcountry in Civil

War–Era Tennessee (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 127–28; C. Peter Ripley,

Slaves and Freedmen in Civil War Louisiana (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press,

1976), p. 196; Zuczek, State of Rebellion, p. 29.

73

Maj W. Gray to Lt Col G. Curkendall, 6 Dec 1865, and Maj W. Gray to Capt P. Slaughter, 6

Dec 1865, both in NA M798, roll 1; W. F. Avent to Brig Gen D. Tillson, 8 Dec 1865, NA M798, roll

24; Maj W. Gray to Brig Gen D. Tillson, 30 Jan 1866 (“afraid, and”), NA M798, roll 27; Capt G. H.

Pratt to Brig Gen D. Tillson, 1 Feb 1866, NA M798, roll 28 (“that the white”); Tillson to Howard,

28 Nov 1865 (“regulators”).

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

490

was acting as a labor recruiter for planters in western Tennessee. Traveling himself

with an escort of two white soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 16th U.S. Infantry, he

agreed with Gray’s assertion, telling General Tillson that the inspector met with

“undisguised disrespect and was at one period . . . in danger of mob violence.”

74

Gray ventured some ninety miles west of Augusta in March, accompanied by

ten soldiers from the same regular battalion that had provided Reeve’s escort in

January. The purpose of this trip was to inspect labor contracts for fair wages and

other terms of employment and to spread the word that if wages were too low

in central Georgia, there were “abundant opportunities” for men to earn fteen

dollars a month, and women twelve, in the southwestern counties. The day after

Gray arrived at the rst county seat on his itinerary, he reported, some of the black

residents told him “that a number of the [white] citizens intended to notify me that

I should have a certain time in which to leave, and that if I did not . . . I should be

mobbed.” When crowds of farmhands gathered to have their contracts inspected,

white employers grew alarmed and threatened Reeve, who was hiring laborers

along with several other recruiters. Overhearing the threats, Gray marshaled his

tiny escort and spoke to “several of the leading citizens,” telling them, “‘Look here

Gentlemen . . . you can’t intimidate me. . . . If my little garrison of Ten men is not

strong enough, I shall get more troops, and let me tell you, that you are bidding fair

to have your Town garrisoned by a Battalion of Colored troops for the remainder

of the year.’ [T]his latter remark worked like a charm.” The threat averted immedi-

ate violence, but Reeve and the other labor recruiters asked for and received the

protection of Gray’s escort on the next leg of their journey.

75

Although Gray’s threat of “a Battalion of Colored troops” had the desired ef-

fect, it was transparent bluster. The Army had been withdrawing troops from Geor-

gia steadily since the previous summer, as it had done throughout the South. In

August 1865, the occupying force in Georgia had been twenty-one white volunteer

infantry regiments; four recently raised black infantry regiments, the 103d USCI

complete and the other three still organizing; one regiment of regular cavalry, and

one battery of regular artillery. These formed the garrisons of nine towns, scattered

in all parts of the state. By the end of the year, their number had dwindled to ve

volunteer infantry regiments, including the 103d USCI, and a newly arrived eight-

company battalion of regular infantry. These amounted to a total of 3,758 ofcers

and men posted at Atlanta, Augusta, Macon, and Savannah, leaving large tracts of

the state without a nearby garrison. In April 1866, the last volunteers mustered out,

leaving the all-white 1st Battalion, 16th U.S. Infantry—four hundred ten ofcers

and men scattered at six towns and Fort Pulaski, at the mouth of the Savannah Riv-

er—to police the entire state, an area of nearly fty-eight thousand square miles.

76

As more black regiments mustered out during the rst half of the year, white

residents of several Southern cities attacked the freedpeople in their midst. The

worst of these occurrences, and the only one that involved an appreciable number

74

Gray to Tillson, 30 Jan 1866; A. T. Reeve to Brig Gen D. Tillson, 31 Jan 1866, NA M798,

roll 28.

75

Maj W. Gray to Brig Gen D. Tillson, 14 Mar 1866, NA M798, roll 27.

76

Maj Gen J. B. Steedman to Maj Gen W. D. Whipple, 8 Aug 1865, and Maj Gen C. R. Woods to

“General,” 2 May 1866, Entry 1708, Dept of Georgia, LS, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Maj Gen C. R. Woods