Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

South Texas, 1864–1867

451

ists evacuated Bagdad and Matamoros. In the course of the summer, the Liberals

nally gained control of all of northern Mexico.

68

The expulsion of the Imperialists by no means resulted in a reign of law and

order. The new governor of Tamaulipas imposed a policy of forced “loans” and

conscation that hurt the leading merchants of Matamoros, many of whom were

United States citizens who had favored the Imperialists and had grown rich trad-

ing in cotton and arms on behalf of the Confederacy. The president of Mexico,

Benito Juárez, himself disowned the governor’s actions. Another local strongman

proclaimed himself governor, but before he could march on Matamoros, other par-

ties there overthrew the incumbent, who escaped across the river to Brownsville.

Juárez detested the new regime in Matamoros as much as he had the old one, and

in November Escobedo led an army of thirty-ve hundred men toward the city.

69

With a battle imminent, the merchants of Matamoros looked for means of stav-

ing off the new governor’s defeat until they could collect debts amounting to some

$600,000 that he had accrued during his three months in ofce. The merchants found

their means in Col. Thomas D. Sedgwick, of the 114th USCI, who commanded the

post at Brownsville. The merchants convinced Sedgwick that the governor’s troops

might riot and pillage the town. No doubt remembering the days of disorder at Bag-

dad in January, the colonel agreed to send a small force across the river. Although

he wrote to Sheridan on 22 November, telling him of his plan, his letter could barely

have reached Sheridan’s desk in New Orleans by the time he acted.

70

The black infantry companies in the Brownsville garrison were responsible for a

military pontoon bridge that they had brought from Virginia. On the night of 24 No-

vember, two companies of the 19th and 114th USCIs crossed the Rio Grande in boats

and secured a site on the Mexican bank. The next day, they assembled the structure

of boats and planks and 118 ofcers and men of the 4th U.S. Cavalry clattered across

it to occupy Matamoros. The black infantrymen guarded the south end of the bridge

and a ferry landing two miles from the city while a battery of the 1st U.S. Artillery

positioned its guns at the north end of the bridge. No longer responsible for patrolling

the town themselves, the defenders of Matamoros were able to repel a Liberal attack

on 27 November, inicting some one thousand casualties on Escobedo’s force.

71

Weeks earlier, Sheridan had warned Sedgwick that the United States pursued a

course of strict neutrality in Mexico’s quarrels but contradicted himself somewhat

by emphasizing that the policy was in force especially “against the adherents of the

imperial buccaneer representing the so-called Imperial Government.” When Sheri-

dan learned that Sedgwick had acceded to the request of the Imperialist sympathizers

of Matamoros, he ordered him to withdraw United States troops across the river at

68

Maj Gen P. H. Sheridan to Lt Gen U. S. Grant, 7 May 1866 (“The Liberals”), NA Microlm

Pub M1635, Headquarters of the Army, LS, roll 94; Thompson, Cortina, pp. 175–81 (“Canales

outlaws,” pp. 175–76).

69

“Occupation of Mexican Territory,” 39th Cong., 2d sess., H. Ex. Doc. 8 (serial 1,287), p. 3;

Thompson, Cortina, pp. 181–85.

70

Col T. D. Sedgwick to Maj Gen P. H. Sheridan, 22 Nov 1866, and Maj Gen P. H. Sheridan

to Gen U. S. Grant, 27 Nov 1866, both in Andrew Johnson Papers, Library of Congress; “Mexico,”

39th Cong., 2d sess., H. Ex. Doc. 17 (serial 1,288), p. 177; Thompson, Cortina, pp. 185–86.

71

NA M594, roll 216, 114th USCI; NA M617, roll 152, Fort Brown, Nov 1866; “Present Condition

of Mexico,” 39th Cong., 2d sess, H. Ex. Doc. 76 (serial 1,292), pp. 550–52, 554; Thompson, Cortina,

pp. 186–88.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

452

once. Sedgwick complied. The day he withdrew his troops, Escobedo and the self-

proclaimed governor entered negotiations. On 1 December, the Liberal army took

possession of Matamoros, peacefully and for the nal time. A few days later, Sheri-

dan took ship for the mouth of the Rio Grande. Once there, he relieved Sedgwick of

command and placed him in arrest. Nevertheless, the general was hardly displeased

with the result of “this unauthorized and harmless intervention,” as he called it in a

letter to Grant’s chief of staff. He released Sedgwick from arrest in January.

72

While all these events were taking place, the muster-out of volunteer regiments

continued. The 10th and 62d USCIs left Texas in the spring of 1866, the ofcers

and men of both regiments traveling north for nal payment and discharge. That

fall, the 7th, 9th, and 36th USCIs followed them. The 19th, 38th, and 116th USCIs

left Texas in January 1867, the 19th sailing for Maryland, the 38th for Virginia, and

the 116th for Kentucky. By that time, the War Department had undertaken a new

project. On 28 July 1866, in an act that determined the size of the Army’s post-

war establishment, Congress for the rst time authorized all-black regiments for

peacetime service. Two of these, the 9th Cavalry and the 39th U.S. Infantry, were

recruiting in New Orleans, the port where the men of the 116th USCI landed on

their way home to Kentucky.

73

Before the Civil War, the Army’s responsibilities had amounted for the most

part to maintaining the country’s coastal defenses and keeping the peace in the West.

With the occupation of the South added to these tasks, Congress in July 1866 au-

thorized a sixty-regiment peacetime force. Two cavalry and four infantry regiments

72

Maj Gen P. H. Sheridan to Col T. D. Sedgwick, 23 Oct 1866 (quotation) (f/w G–204–AUS–

1866), NA M1635, roll 94; “Mexico,” pp. 3–5 (quotation); Thompson, Cortina, pp. 188–89.

73

ORVF, 8: 176, 179–80, 190, 207, 209, 235, 297.

The pontoon bridge at Brownsville

South Texas, 1864–1867

453

were to be “composed of colored men.” Sheridan was to organize one regiment of

each branch in the Division of the Gulf, both of them headquartered at or near New

Orleans. A War Department order offered immediate discharges to men of volunteer

regiments who intended to join the regulars, and one hundred thirty men of the 116th

availed themselves of it. The vast majority of them went directly into the 39th U.S.

Infantry. In cities from New Orleans to Boston, about twenty-ve hundred veterans

of the U.S. Colored Troops joined the six black regular regiments in 1866 and 1867,

contributing more than 40 percent of the total number of recruits and providing most

of the noncommissioned ofcers. Two companies of the 9th U.S. Cavalry arrived at

Brownsville in April 1867, just four months before the 117th USCI, the last regiment

of the U.S. Colored Troops in Texas, mustered out. In July, companies of the 41st

U.S. Infantry, another of the new black regular regiments, relieved companies of the

117th at Fort McIntosh and Ringgold Barracks.

74

Throughout the rst few months of 1867, the Imperialist cause in Mexico con-

tinued to collapse. Sheridan thought that Maximilian might embark for Europe as

his foreign troops withdrew from Mexico, but the emperor decided to make a stand

at Querétaro, some one hundred thirty miles northwest of Mexico City. Besieged

there for more than two months, he surrendered in mid-May. A ring squad shot

him on 19 June. A few days later, the garrison of Brownsville was able to see re-

works and hear the sounds of celebration in Matamoros.

75

Within six weeks, the 117th USCI mustered out and its ofcers and men took

ship for Kentucky to receive nal payment and discharges. Since that spring, the

117th had been the last volunteer regiment in Texas. Its duties on the Rio Grande

seemed far removed from the cause for which its ofcers and men had joined the

Army, but Sheridan was convinced that the successful suppression of the Confed-

eracy and the Liberal victory in Mexico ran parallel to each other. “While we were

struggling for a republican existence against organized rebellion,” he wrote in his

report of November 1866,

the Emperor of the French undertook the bold expedition to subvert the Repub-

lic of Mexico. . . . The effect of the presence of our troops in Texas and on the

Rio Grande . . . on the destiny of imperialism was great . . . , so much so, that

. . . had a demand been made for the withdrawal of the Imperial troops, on the

ground that the invasion of Mexico was part of the rebellion, it would have been

granted and the miseries of that country for the last year avoided.

While ofcers and men of the black regiments openly favored the Liberal party

in the struggle for control of Mexico, they managed to avoid direct involvement

in all but a few episodes. Nevertheless, their presence on the north bank of the

Rio Grande inuenced the calculations of Napoleon III when he announced the

74

116th USCI, Entry 57, Muster Rolls of Volunteer Organizations, RG 94, NA. NA M617,

roll 155, Post of Brownsville, April 1867; roll 681, Fort McIntosh, Jul 1867; roll 1020, Ringgold

Barracks, Jul 1867. William A. Dobak and Thomas D. Phillips, The Black Regulars, 1866–1898

(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001), pp. xii–xv, 1–2, 13, 24.

75

Maj Gen P. H. Sheridan to Maj Gen J. A. Rawlins, 4 Jan 1867 (G–7–AUS–1867), NA M1635,

roll 98; Thompson, Cortina, pp. 189–92.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

454

withdrawal of French troops from Mexico. In that sense, it helped to hasten the

end of the conict there.

76

Mustered-out regiments of black soldiers sailed from Texas for Philadelphia,

Baltimore, or Louisville, where ofcers and men received their nal pay and dis-

charges. As the veterans reached home, they found life there changed because of

their efforts during the war. For many former enlisted men, the most dramatic

change was in their status, and that of their families’, from slave to free. This was

especially true in the states of the former Confederacy that came under military

occupation. While some black regiments stood guard on the Rio Grande, others

served in posts across the defeated South, assisting the federal attempt to impose a

new regime of freedom.

76

OR, ser. 1, vol. 48, pt. 1, p. 300 (quotation); Krause, Mexico, pp. 177–86; Vanderwood,

“Betterment for Whom?” pp. 386–91.

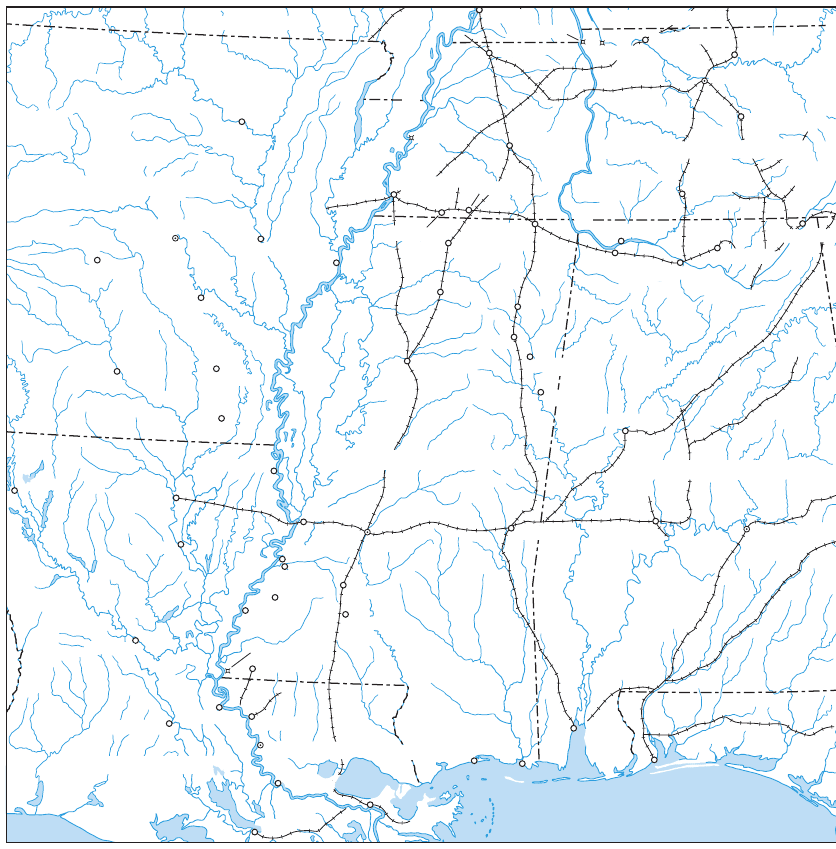

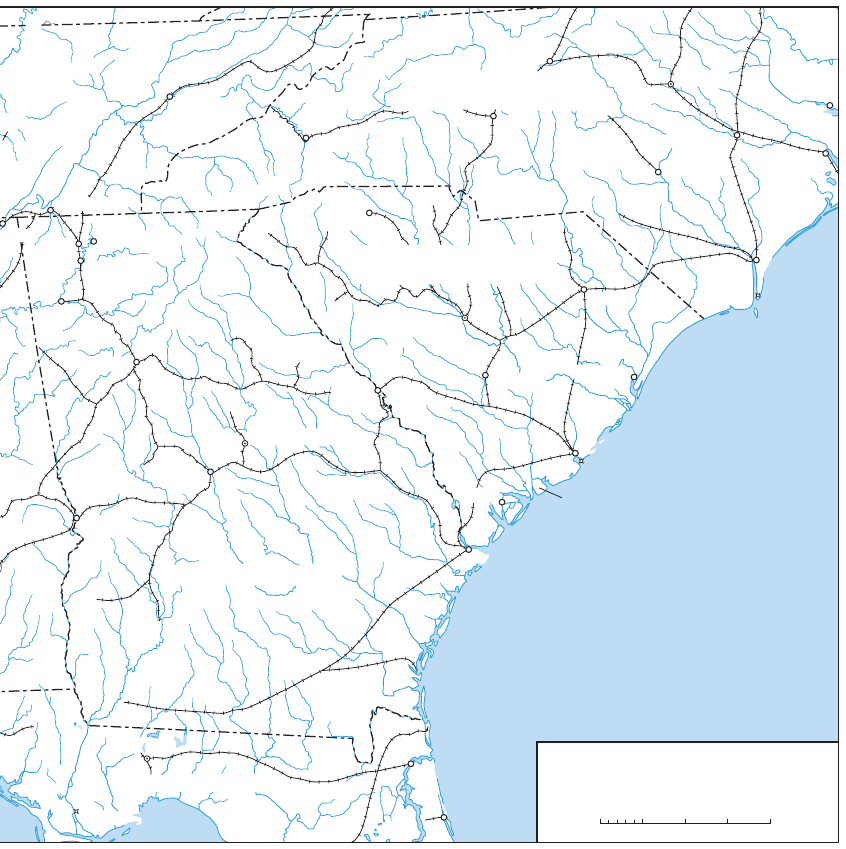

The business of Reconstruction began before the federal government had

settled on a policy of Emancipation or organized a single regiment of black sol-

diers. The chief concern at rst was to create stable, loyal governments in states

that had left the Union. Efforts to install such governments began early in 1862,

not long after Nashville became the rst capital of a seceded state to fall to a fed-

eral army. On 4 March, Andrew Johnson, who had remained in the U.S. Senate

when Tennessee seceded, received an appointment as brigadier general of U.S.

Volunteers and assumed the post of military governor of that state. Later in the

war, other attempts to install Unionist state governments gave impetus to federal

military offensives in Florida and Louisiana (see Map 10).

1

As Union armies moved south, they met the black residents of each state. On

the Sea Islands of South Carolina, soldiers found slaves tending their own garden

plots on plantations from which white owners had ed. In other parts of the Con-

federacy, escaped slaves thronged the camps of the advancing troops or settled

in shantytowns on the outskirts of occupied cities. Whether black Southerners

waited for the liberators to arrive or rushed to meet them, Union soldiers saw the

former slaves as a problem that required food, shelter, and direction in perform-

ing useful labor. While putting to work the able-bodied residents of plantations

and camps and providing food and shelter for others, federal administrators also

had to decide what to do with the plantations of disloyal owners. Congress had

declared these lands forfeit to the federal government and provided for their sale

or lease in a series of laws enacted between August 1861 and July 1864. Often,

administrators used these plantations as settlement sites for former slaves, who

1

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Ofcial Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1880–1901),

ser. 1, 7: 424–33; vol. 10, pt. 2, p. 612 (hereafter cited as OR). Leroy P. Graf et al., eds., The

Papers of Andrew Johnson, 16 vols. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1967–2000), 5:

177, 182 (hereafter cited as Johnson Papers); Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unnished

Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), pp. 35–37, 43–50; Peter Maslowski,

Treason Must Be Made Odious: Military Occupation and Wartime Reconstruction in Nashville,

Tennessee, 1862– 65 (Millwood, N.Y.: KTO Press, 1978), pp. 19–20; Ted Tunnell, Crucible of

Reconstruction: War, Radicalism, and Race in Louisiana, 1862–1877 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana

State University Press, 1984), pp. 44–50.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

Chapter 14

M

i

s

s

i

s

s

i

p

p

i

R

B

i

g

B

l

a

c

k

R

T

e

n

n

e

s

s

e

e

R

T

e

n

n

e

s

s

e

e

R

C

u

m

b

e

r

l

a

n

d

R

P

e

a

r

l

R

T

i

m

b

i

g

b

y

R

B

l

a

c

k

W

a

r

r

i

o

r

R

F

l

i

n

t

R

A

p

p

a

l

a

c

h

i

c

o

l

a

R

C

o

o

s

a

R

F

l

i

n

t

R

M

o

b

i

l

e

R

A

l

a

b

a

m

a

R

O

u

a

c

h

i

t

a

R

A

r

k

a

n

s

a

s

R

R

e

d

R

S

a

b

i

n

e

R

Y

a

z

o

o

R

W

h

i

t

e

R

R

o

a

n

o

k

e

R

S

a

v

a

n

n

a

h

R

Cape Fear

Edisto Island

Fort Henry

Fort Donelson

Fort Pillow

Fort Adams

Fort Gadsden

Fort Fisher

Fort Sumter

Columbus

Clarksville

Gallatin

Murfr

eesborough

Pulaski

Bridgeport

Jackson

La Grange

Union City

La Fayette

Batesville

Oxford

Meridian

Corinth

Tuscaloosa

Rome

Resaca

Asheville

Spartanburg

Salisbury

Florence

Georgetown

Orangeburg

Beaufort

Greensboro

Goldsborough

Washington

Dalton

Spring Place

Decatur

Okolona

Tupelo

Grenada

Pascagoula

Pensacola

Helena

Duvall’s Blu

Lake Providence

Monroe

Shreveport

Columbia

Port Gibson

Brookhaven

Hazlehurst

Fayette

Woodville

Port Hudson

Morganza

Donaldsonville

Mississippi City

Brashear

Washington

Alexandria

Grand Gulf

Camden

Monticello

Pine Blu

Hot Springs

Hamburg

Knoxville

Fayetteville

Wilmington

Charleston

Augusta

Savannah

Chattanooga

Atlanta

Macon

Jacksonville

St. Augustine

Columbus

Selma

Mobile

Holly Springs

Memphis

Huntsville

Florence

Tuscumbia

Columbus

Aberdeen

Vicksburg

New Orleans

Natchez

New Berne

MONT

GOMERY

TALLAHASSEE

BATON ROUGE

JACKSON

NASHVILLE

RALEIGH

COLUMBIA

MILLEDGEVILLE

LITTLE ROCK

MISSOURI

GEORGIA

FLORIDA

KENTUCKY

VIRGINIA

TENNESSEE

NORTH

CAROLINA

SOUTH

CAROLINA

ALABAMA

LOUISIANA

MISSISSIPPI

ARKANSAS

TEXAS

RECONSTRUCTION

1865–1867

0

100755025

Miles

Map 10

M

i

s

s

i

s

s

i

p

p

i

R

B

i

g

B

l

a

c

k

R

T

e

n

n

e

s

s

e

e

R

T

e

n

n

e

s

s

e

e

R

C

u

m

b

e

r

l

a

n

d

R

P

e

a

r

l

R

T

i

m

b

i

g

b

y

R

B

l

a

c

k

W

a

r

r

i

o

r

R

F

l

i

n

t

R

A

p

p

a

l

a

c

h

i

c

o

l

a

R

C

o

o

s

a

R

F

l

i

n

t

R

M

o

b

i

l

e

R

A

l

a

b

a

m

a

R

O

u

a

c

h

i

t

a

R

A

r

k

a

n

s

a

s

R

R

e

d

R

S

a

b

i

n

e

R

Y

a

z

o

o

R

W

h

i

t

e

R

R

o

a

n

o

k

e

R

S

a

v

a

n

n

a

h

R

Cape Fear

Edisto Island

Fort Henry

Fort Donelson

Fort Pillow

Fort Adams

Fort Gadsden

Fort Fisher

Fort Sumter

Columbus

Clarksville

Gallatin

Murfreesborough

Pulaski

Bridgepor

t

Jackson

La Grange

Union City

La Fayette

Batesville

Oxford

Meridian

Corinth

Tuscaloosa

Rome

Resaca

Asheville

Spartanburg

Salisbury

Florence

Georgetown

Orangeburg

Beaufort

Greensboro

Goldsborough

Washington

Dalton

Spring Place

Decatur

Okolona

Tupelo

Grenada

Pascagoula

Pensacola

Helena

Duvall’s Blu

Lake Providence

Monroe

Shreveport

Columbia

Port Gibson

Brookhaven

Hazlehurst

Fayette

Woodville

Port Hudson

Morganza

Donaldsonville

Mississippi City

Brashear

Washington

Alexandria

Grand Gulf

Camden

Monticello

Pine Blu

Hot Springs

Hamburg

Knoxville

Fayetteville

Wilmington

Charleston

Augusta

Savannah

Chattanooga

Atlanta

Macon

Jacksonville

St. Augustine

Columbus

Selma

Mobile

Holly Springs

Memphis

Huntsville

Florence

Tuscumbia

Columbus

Aberdeen

Vicksburg

New Orleans

Natchez

New Berne

MONTGOMER

Y

TALLAHASSEE

BATON ROUGE

JACKSON

NASHVILLE

RALEIGH

COLUMBIA

MILLEDGEVILLE

LITTLE ROCK

MISSOURI

GEORGIA

FLORIDA

KENTUCKY

VIRGINIA

TENNESSEE

NORTH

CAROLINA

SOUTH

CAROLINA

ALABAMA

LOUISIANA

MISSISSIPPI

ARKANSAS

TEXAS

RECONSTRUCTION

1865–1867

0

100755025

Miles

M

i

s

s

i

s

s

i

p

p

i

R

B

i

g

B

l

a

c

k

R

T

e

n

n

e

s

s

e

e

R

T

e

n

n

e

s

s

e

e

R

C

u

m

b

e

r

l

a

n

d

R

P

e

a

r

l

R

T

i

m

b

i

g

b

y

R

B

l

a

c

k

W

a

r

r

i

o

r

R

F

l

i

n

t

R

A

p

p

a

l

a

c

h

i

c

o

l

a

R

C

o

o

s

a

R

F

l

i

n

t

R

M

o

b

i

l

e

R

A

l

a

b

a

m

a

R

O

u

a

c

h

i

t

a

R

A

r

k

a

n

s

a

s

R

R

e

d

R

S

a

b

i

n

e

R

Y

a

z

o

o

R

W

h

i

t

e

R

R

o

a

n

o

k

e

R

S

a

v

a

n

n

a

h

R

Cape Fear

Edisto Island

Fort Henry

Fort Donelson

Fort Pillow

Fort Adams

Fort Gadsden

Fort Fisher

Fort Sumter

Columbus

Clarksville

Gallatin

Murfreesborough

Pulaski

Bridgeport

Jackson

La Grange

Union City

La Fayette

Batesville

Oxford

Meridian

Corinth

Tuscaloosa

Rome

Resaca

Asheville

Spartanburg

Salisbury

Florence

Georgetown

Orangeburg

Beaufort

Greensboro

Goldsborough

Washington

Dalton

Spring Place

Decatur

Okolona

Tupelo

Grenada

Pascagoula

Pensacola

Helena

Duvall’s Blu

Lake Providence

Monroe

Shreveport

Columbia

Port Gibson

Brookhaven

Hazlehurst

Fayette

Woodville

Port Hudson

Morganza

Donaldsonville

Mississippi City

Brashear

Washington

Alexandria

Grand Gulf

Camden

Monticello

Pine Blu

Hot Springs

Hamburg

Knoxville

Fayetteville

Wilmington

Charleston

Augusta

Savannah

Chattanooga

Atlanta

Macon

Jacksonville

St. Augustine

Columbus

Selma

Mobile

Holly Springs

Memphis

Huntsville

Florence

Tuscumbia

Columbus

Aberdeen

Vicksburg

New Orleans

Natchez

New Berne

MONTGOMERY

TALLAHASSEE

BATON ROUGE

JACKSON

NASHVILLE

RALEIGH

COLUMBIA

MILLEDGEVILLE

LITTLE ROCK

MISSOURI

GEORGIA

FLORIDA

KENTUCKY

VIRGINIA

TENNESSEE

NORTH

CAROLINA

SOUTH

CAROLINA

ALABAMA

LOUISIANA

MISSISSIPPI

ARKANSAS

TEXAS

RECONSTRUCTION

1865–1867

0

100755025

Miles

M

i

s

s

i

s

s

i

p

p

i

R

B

i

g

B

l

a

c

k

R

T

e

n

n

e

s

s

e

e

R

T

e

n

n

e

s

s

e

e

R

C

u

m

b

e

r

l

a

n

d

R

P

e

a

r

l

R

T

i

m

b

i

g

b

y

R

B

l

a

c

k

W

a

r

r

i

o

r

R

F

l

i

n

t

R

A

p

p

a

l

a

c

h

i

c

o

l

a

R

C

o

o

s

a

R

F

l

i

n

t

R

M

o

b

i

l

e

R

A

l

a

b

a

m

a

R

O

u

a

c

h

i

t

a

R

A

r

k

a

n

s

a

s

R

R

e

d

R

S

a

b

i

n

e

R

Y

a

z

o

o

R

W

h

i

t

e

R

R

o

a

n

o

k

e

R

S

a

v

a

n

n

a

h

R

Cape Fear

Edisto Island

Fort Henry

Fort Donelson

Fort Pillow

Fort Adams

Fort Gadsden

Fort Fisher

Fort Sumter

Columbus

Clarksville

Gallatin

Murfreesborough

Pulaski

Bridgepor

t

Jackson

La Grange

Union City

La Fayette

Batesville

Oxford

Meridian

Corinth

Tuscaloosa

Rome

Resaca

Asheville

Spartanburg

Salisbury

Florence

Georgetown

Orangeburg

Beaufort

Greensboro

Goldsborough

Washington

Dalton

Spring Place

Decatur

Okolona

Tupelo

Grenada

Pascagoula

Pensacola

Helena

Duvall’s Blu

Lake Providence

Monroe

Shreveport

Columbia

Port Gibson

Brookhaven

Hazlehurst

Fayette

Woodville

Port Hudson

Morganza

Donaldsonville

Mississippi City

Brashear

Washington

Alexandria

Grand Gulf

Camden

Monticello

Pine Blu

Hot Springs

Hamburg

Knoxville

Fayetteville

Wilmington

Charleston

Augusta

Savannah

Chattanooga

Atlanta

Macon

Jacksonville

St. Augustine

Columbus

Selma

Mobile

Holly Springs

Memphis

Huntsville

Florence

Tuscumbia

Columbus

Aberdeen

Vicksburg

New Orleans

Natchez

New Berne

MONTGOMER

Y

TALLAHASSEE

BATON ROUGE

JACKSON

NASHVILLE

RALEIGH

COLUMBIA

MILLEDGEVILLE

LITTLE ROCK

MISSOURI

GEORGIA

FLORIDA

KENTUCKY

VIRGINIA

TENNESSEE

NORTH

CAROLINA

SOUTH

CAROLINA

ALABAMA

LOUISIANA

MISSISSIPPI

ARKANSAS

TEXAS

RECONSTRUCTION

1865–1867

0

100755025

Miles

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

458

grew food for themselves as well as staple crops, chiey cotton, that helped pay

for the Union war effort.

To govern the freedpeople and the land on which they lived, and to provide for

thousands of white Unionist refugees forced from their homes, Congress passed and

President Lincoln signed on 3 March 1865 an act that established the Bureau of Ref-

ugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, a title soon shortened in popular usage to

the Freedmen’s Bureau. Deliberations on the bill had extended through two sessions

of Congress. Introduced in December 1863 to establish a “Bureau of Emancipation,”

its provisions grew during the next fourteen months to include responsibility both for

destitute white Unionists in the South and for plantations that had fallen to the federal

government for nonpayment of taxes, or through abandonment by a disloyal owner, or

because the owner was a civil or military ofcer of one of the seceded states or of the

Confederacy itself. In the end, legislators felt so condent that revenues from manage-

ment of abandoned and forfeited lands would sufce to fund the new agency that they

failed to appropriate any money for its operations and its agents’ salaries. This lack of

budget meant that the Bureau had to be staffed by Army ofcers who were already on

the federal payroll. The new agency itself became part of the War Department.

2

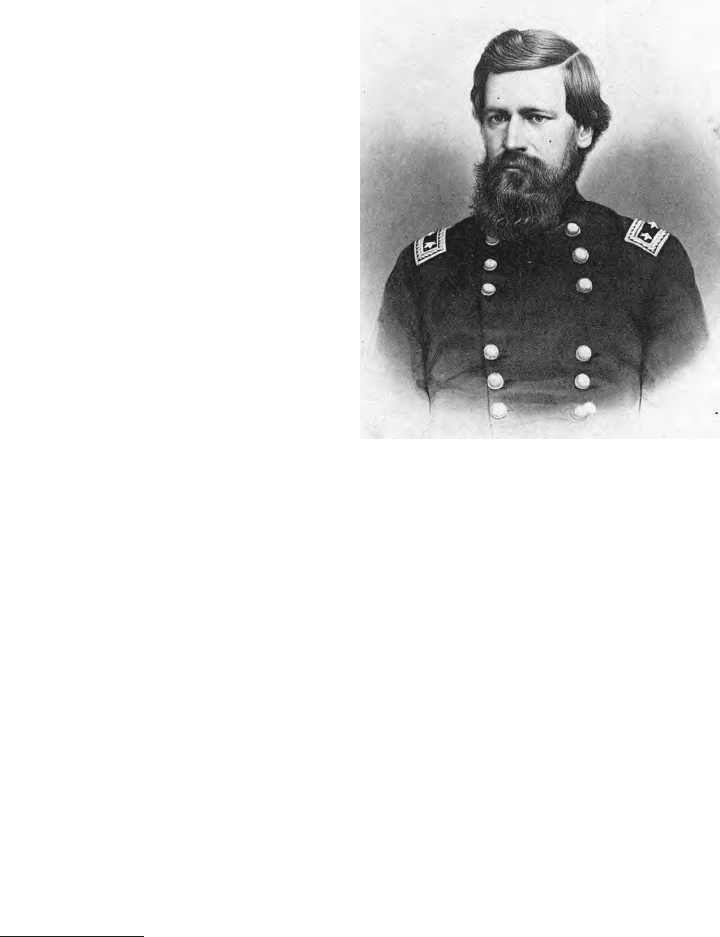

At the Bureau’s head was a commissioner, Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, who

had led the Army of the Tennessee on its march through Georgia and the Carolinas

during the last months of the war. “I hardly know whether to congratulate you or

not,” Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman wrote when he learned of his subordinate’s

appointment, “but . . . I cannot imagine that matters that may involve the future of

4,000,000 of souls could be put in more charitable and more conscientious hands.”

Assistant commissioners reporting to Howard in Washington would be in charge

of the Bureau’s affairs in the states. Local administration would be in the hands of

eld agents, each one responsible for several counties. Most of these agents were

ofcers of the Veteran Reserve Corps, an organization of wounded soldiers t for

light duty, or of the U.S. Colored Troops.

3

As paroled Confederate soldiers returned home in the spring of 1865, one hundred

thousand ofcers and men of the Army’s black regiments occupied dozens of camps

scattered from Key West, Florida, to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The largest body of

troops was the XXV Corps, twenty-nine regiments of cavalry, infantry, and heavy artil-

lery and one battery of light artillery, aboard ships bound for Texas, leaving no black

regiments in Virginia. The next-largest command numbered 21 regiments, with compa-

nies of 3 others, in Louisiana and 21 regiments and 3 batteries in Tennessee. Mississip-

pi played unwilling host to 12 regiments and several companies of another, as well as

2 batteries; North Carolina, to 10 regiments; Kentucky and South Carolina, to 9 each;

Arkansas, to 8 regiments and companies of 2 others, as well as 2 batteries; Florida,

to 6 regiments; and Alabama and Georgia, to 4 regiments each. A little farther north,

the 123d United States Colored Infantry (USCI), recently raised in Kentucky, guarded

2

George R. Bentley, A History of the Freedmen’s Bureau (New York: Octagon Books, 1974

[1944]), pp. 36–49; Steven Hahn et al., eds., Land and Labor, 1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press, 2008), pp. 17–19. The text of the Freedmen’s Bureau Act appears in OR, ser. 3, vol.

5, pp. 19–20; the two Conscation Acts (August 1861 and July 1862), the Direct Tax Act (June 1862),

and subsequent acts implementing them are in U.S. Statutes at Large 12: 319, 422–26, 589–92; 13:

320–21, 375–78.

3

OR, ser. 1, vol. 47, pt. 3, p. 515 (quotation); Hahn et al., Land and Labor, pp. 19–20.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

459

the quartermaster depot at Jefferson-

ville, Indiana, and the 24th USCI, a

Philadelphia regiment, monitored the

repatriation of Confederate prisoners

of war at Point Lookout, Maryland,

while guarding public property there.

4

Wherever soldiers were sta-

tioned, safeguarding government

buildings and supplies was an im-

portant part of their duties, for

nineteenth-century Americans were

quick to appropriate for themselves

whatever might be described as

public, whether movable goods or

real estate. As a result, soldiers in

many black regiments spent most

of their time as sentinels during

the months after the Confederate

surrender. Men of the 59th USCI,

veterans of Brice’s Crossroads and

Tupelo in the summer of 1864,

stood watch over the navy yard at

Memphis ten months later. The 81st

USCI, a regiment that evoked favor-

able comment from both generals

and inspectors, guarded warehouses, ordnance depots, and government ofces at

eighteen sites in and near New Orleans. The Freedmen’s Bureau headquarters in

Washington became the responsibility of the 107th USCI, one of the last volunteer

regiments, black or white, to muster out. Along with surplus ordnance stored at

several of the forts that ringed the capital, the 107th also guarded Freedmen’s Vil-

lage, which stood across the Potomac on the Virginia estate of Confederate Gener-

al Robert E. Lee. Apart from sentry duty at settlements of displaced former slaves

and the informal off-duty relations of enlisted men with nearby residents during

the months before mustering out, these regiments had little to do with enforcing

federal Reconstruction policies.

5

The exact nature of those policies remained unclear as spring turned to sum-

mer. The Congress that had been elected in 1864 was not scheduled to convene

until December 1865, leaving the initiative to President Andrew Johnson. A Demo-

4

Mean strength of black troops in May 1865 was 98,316; in June, 105,009. The Medical and

Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 2 vols. in 6 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing

Ofce, 1870–1888), 1: 685. Troop stations, 30 Jun 1865, in National Archives (NA) Microlm Pub

M594, Compiled Rcds Showing Svc of Mil Units in Volunteer Union Organizations, rolls 204–17.

This count differs slightly from that provided by the map in Noah A. Trudeau, Like Men of War:

Black Troops in the Civil War, 1862–1865 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1998), p. 457, which portrays the

stations in May.

5

Capt C. P. Brown to Col I. G. Kappner, 29 Aug 1865, 59th United States Colored Infantry

(USCI); Maj W. Hoffman to Lt Col B. Gaskill, 11 Jun 1865, and Capt H. K. Smithwick to Capt B. B.

Campbell, 14 Aug 1865, both in 81st USCI; Dept of Washington, Special Orders (SO) 196, 18 Oct

Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, Commissioner

of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and

Abandoned Lands from 1865 to 1872

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

460

crat from the mountains of eastern Tennessee and wartime military governor of

the state, Johnson had seemed a good choice for Lincoln’s running mate on the

National Union ticket, a Republican Party surrogate, the previous year. When the

nominating convention met in June 1864, Northern newspapers had been printing

long casualty lists from Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Virginia Campaign for a month

and Sherman’s attempt to seize Atlanta was still far from achieving a result. The

administration needed every vote it could get, so the Tennessean replaced Vice

President Hannibal Hamlin, a Republican from Maine, on the ticket. The election

of Lincoln and Johnson and Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865 put Johnson in

a position to reconstruct the conquered South by himself, without congressional

interference, for nearly eight months.

6

The new president embodied an observation expressed by many federal of-

cers during the war and after, that a staunch Southern Unionist was not neces-

sarily an abolitionist, or even well intentioned toward black people. Having risen

from poverty himself, Johnson as an elected ofcial represented the interests of

the white residents of the poorest section of his state. As a candidate for the vice

presidency in October 1864, he had told an audience of black Tennesseans, “I will

indeed be your Moses, and lead you through the Red Sea of war and bondage, to

a fairer future of liberty and peace.” Yet nearly sixteen months later—ten of them

spent as president following Lincoln’s assassination—after meeting a delegation

headed by the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, he told his secretary, “I know

that d——d Douglass; he’s just like any nigger, and he would sooner cut a white

man’s throat as not.” In the fall of 1865, a captain of the 40th USCI serving as

Freedmen’s Bureau agent at Knoxville reported his inability to accomplish much

among “a people so hostile to the negroe as are the East Tennesseans.” The new

president was true to the type.

7

Johnson’s rst weeks in ofce confused onlookers. Late in April, he disowned

the too-lenient surrender agreement General Sherman had offered to Confederate

troops in North Carolina and sent Grant south to impose more stringent terms.

Southerners, black and white, awaited the president’s next move with anxiety.

Then, on 29 May, Johnson issued an amnesty proclamation and announced a plan

to install state governments throughout the former Confederacy. The amnesty

terms were generous, exempting only certain categories of persons, among them

the Confederacy’s highest-ranking ofcials, civil and military ofcers of the fed-

eral government who had embraced the Confederate cause, and owners of more

than twenty thousand dollars’ worth of property. Such persons could apply to the

president for individual pardon. In a second proclamation that day, Johnson ap-

pointed a provisional governor for North Carolina, whose duty it would be to sum-

mon a convention to draft a new state constitution that would repudiate secession

1866, 107th USCI; all in Entry 57C, Regimental Papers, Record Group (RG) 94, NA. On the 59th

USCI at Brice’s Crossroads and Tupelo, see above, Chapter 7; on the reputation of the 81st USCI,

see above, Chapter 13.

6

Foner, Reconstruction, pp. 43–45, 176–84, 228.

7

David W. Bowen, Andrew Johnson and the Negro (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press,

1989), pp. 6 (“I know”), 51, 81 (“I will”); Capt D. Boyd to Capt W. T. Clarke, 5 Oct 1865 (B–136),

NA Microlm Pub T142, Selected Rcds of the Tennessee Field Ofce of the Bureau of Refugees,

Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (BRFAL), roll 25.