Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

421

Springeld, Illinois. On 16 April, one of Grant’s aides sent a telegram to Ord in

Richmond: “Please send . . . immediately one of the best regiments of colored

troops you have, to attend the funeral ceremonies. . . . One that has seen service

should be selected.” Weitzel’s choice was the 22d USCI, a regiment raised in Phila-

delphia that had taken part in the previous year’s ghting around Petersburg and

Richmond. “We felt highly complimented,” Assistant Surgeon James O. Moore

told his wife, “to be among the rst organized troops to march thru Richmond &

now . . . to participate in the funeral obsequies of the President.”

98

The regiment embarked before dawn on 18 April and reached Washington at

about noon the next day. Marching north from the wharf as all the church bells in

the city tolled and cannon red every sixty seconds, the 22d USCI met the funeral

procession at Seventh Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, making its way east from

the White House to the Capitol. “Halted[,] wheeled into col[umn],” one ofcer of

the regiment noted, “and became the head of [the] procession. After funeral [the]

men were quartered at Soldiers’ Rest. Ofcers at Hotels.” A Washington newspa-

per commented that the troops “appeared to be under the very best discipline, and

displayed admirable skill in their various exercises.”

99

Three days later, they boarded a boat for Charles County, Maryland, to join

the hunt for the president’s assassin. Surgeon Moore surmised that they had been

sent because the men of the regiment “would be more likely [than white troops] to

get information from the colored population.” Ofcers and men spent the next four

days splashing through swamps until, on 26 April, news reached them of the assas-

98

OR, ser. 1, vol. 46, pt. 3, pp. 797 (quotation), 816; J. O. Moore to My Dearest Lizzie, 20 Apr

1865, J. O. Moore Papers, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

99

NA M594, roll 8, 22d USCI; (Washington) Daily National Intelligencer, 20 April 1865.

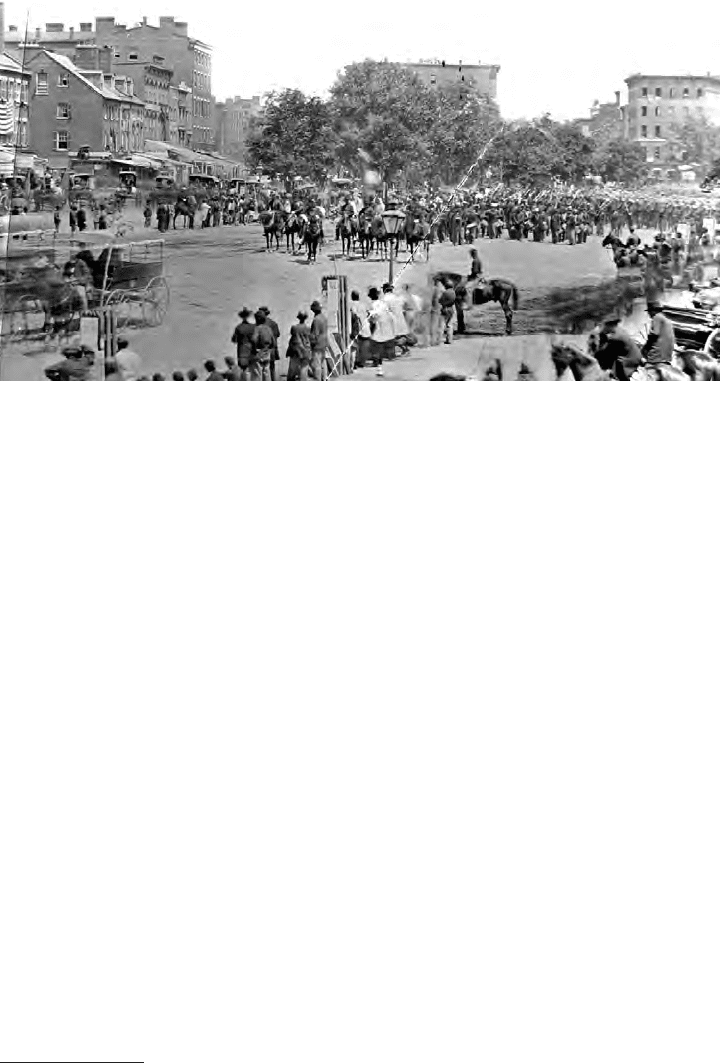

Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., spring 1865

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

422

sin’s death. They returned to their landing place on the Potomac and waited there

until late May, when they took ship again for City Point, Virginia.

100

While the 22d USCI camped by the Potomac, arguments ew along the James

about the future of the XXV Corps. Maj. Gen. George L. Hartsuff, commanding

at Petersburg, complained to Weitzel on 13 May about the conduct of Weitzel’s

men, especially “destruction of buildings and . . . exciting the colored people to

acts of outrage against the persons and property of white citizens. Colored soldiers

. . . [have] straggled about advising negroes not to work on the farms,” and offer-

ing to arm the former slaves. Weitzel replied that the destruction was the work of

“black and white cavalry, which . . . did not belong to my corps,” or of “convicts

in soldiers’ clothing” who had been freed by retreating Confederates during the

evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond. He enclosed a telegram in which Ord

had told him: “I do not consider the behavior of the colored corps . . . to be bad,

considering the novelty of their position and the fact that most of their company of-

cers had come from positions where they were unaccustomed to command” and

that occupation duty offered “perhaps the rst great temptation to which [the] men

were exposed. In the city of Richmond their conduct is spoken of as very good.”

101

That was not what Ord had said to Halleck three weeks earlier, when Halleck

succeeded him in command of the Department of Virginia. On 29 April, Halleck

had told Grant about Ord’s poor opinion of Weitzel’s troops, adding the next day:

“On further consultation with . . . Ord, I am more fully convinced of the policy of

the withdrawal of the [XXV] Corps from Virginia. Their conduct recently has been

even worse than I supposed yesterday.” General Meade agreed, telling Grant that

his troops, “hearing of marauders, . . . succeeded in capturing a camp with several

wagons loaded with plunder. The party consisted of negroes, mostly belonging

to this army.” Even though white cavalry commanders had received warnings to

“use great care that no depredations are committed” and Ord himself had removed

Col. Charles Francis Adams Jr. from command of the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry

(Colored) for letting his men “straggle and maraud,” even though ofcers of the

22d USCI, riding in the country near Richmond, had met a group of cavalrymen

(race unspecied, therefore probably white) looting a house and had driven them

off; still blame settled on the men of the XXV Corps. The recent gang rape and

court-martial did nothing to dispel it.

102

Throughout the war, Halleck had favored sweeping solutions and peremptory

orders. In the fall of 1861, rather than deal with escaped slaves and the claims of

their supposed owners in Missouri, he had issued an order that barred commanding

ofcers from admitting any black people to military posts. When he arrived in Vir-

ginia in the spring of 1865, his plan for getting crops planted and preventing fam-

ine later in the year was to prevent recently freed black people from moving to the

cities, forcing them to work on the land. With the war over and black men admitted

to the Army, the quickest way for him to dispose of complaints about their miscon-

100

NA M594, roll 8, 22d USCI; J. O. Moore to My Dearest Lizzie, 23 Apr 1865, Moore Papers.

101

OR, ser. 1, vol. 46, pt. 1, pp. 1148 (Hartsuff), 1160–61 (Weitzel, Ord).

102

Ibid., pt. 3, pp. 811 (Meade), 1016 (Halleck). Asst Adj Gen to Col E. V. Sumner, 16 Apr 1865

(“use great care”), Entry 6977, 3d Div, XXIV Corps, LS, pt. 2, RG 393, NA; J. O. Moore to My

Dearest Lizzie, 9 Apr 1865, Moore Papers; Worthington C. Ford, ed., A Cycle of Adams Letters, 2

vols. (Boston: Houghton Mifin, 1920), 1: 267 (“straggle and maraud”).

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

423

duct was to remove them from his department. On 18 May, after consultation with

Halleck, Grant ordered Weitzel to prepare his command to take ship for Texas.

103

By that time, hundreds of thousands of soldiers of every rank, black and white,

were eager to get out of uniform. Some ofcers, who found themselves better off

in the Army than they had ever been in civilian life, wanted to remain. “You had

better approve applications to resign when there is no great advantage in retaining

the ofcer,” Ord told Weitzel in early May, “as we can get rst rate men now from

the white troops being mustered out. I have already had applications of ofcers . . .

highly recommended to transfer to Colored Corps—and there is nothing gained by

retaining discontented ofcers.”

104

Unlike an ofcer, an enlisted men could not submit a resignation on the

chance that it would be accepted. Sixty-three ofcers managed to resign from

regiments of the XXV Corps between 9 April, when Lee surrendered, and 25

May, when the rst transports sailed for Texas, but all enlisted men except those

declared unt by a surgeon were obliged to wait for their discharges until their

regiments mustered out of service. In 1864, when thousands of white soldiers

who had volunteered in 1861 refused to reenlist for another three years, entire

regiments disappeared from the Union Army. The white volunteers of 1862

would be ready for discharge in the fall of 1865; but since nationwide recruit-

ing of black soldiers had only begun early in 1863, even the longest-serving

veteran among them had nearly a year of his enlistment left by the spring of

1865, if the government should decide to retain his regiment. Other black regi-

ments, raised in 1864, might continue to serve well into 1867. That the troops’

obligation was completely legal did nothing to improve their mood.

105

Black soldiers worried especially about their families. The white regiments

of 1861 and 1862 had recruited and organized locally, and local committees

made arrangements to help sustain their dependents. West of the Appalachians

and in Union beachheads along the Atlantic coast, many black soldiers’ fami-

lies lived in contraband camps maintained by the federal government. About

half of the soldiers in the XXV Corps, though, came either from the free states

or from unseceded Maryland, where such institutions did not exist. Even the

equalization of pay for black and white soldiers in 1864 was only of small help,

for six or eight months might pass between paymasters’ visits. The 114th USCI

saw no pay from 1 September 1864 until 20 April 1865. Irregular pay damaged

the morale of black and white soldiers alike, in all parts of the South. General

Ord suggested that soldiers’ wives could be appointed laundresses in their hus-

bands’ companies, for each company in the Army was entitled to several laun-

dresses, paid by deductions from the men’s pay. Laundresses could accompany

their husbands to Texas, the government bearing the expense of their travel,

103

OR, ser. 1, 8: 370; vol. 46, pt. 1, pp. 1005–06, 1168–69, 1172–73.

104

Maj Gen E. O. C. Ord to Maj Gen G. Weitzel, Entry 5046, Dept of Virginia and Army of the

James, LS, pt. 1, RG 393, NA.

105

The number of resignations was calculated by consulting records of the 1st and 2d USCCs;

7th, 8th, 9th, 19th, 22d, 23d, 29th, 31st, 36th, 38th, 41st, 43d, 45th, 109th, 114th, 115th, 116th, 117th,

118th, and 127th USCIs; 5th Massachusetts Cavalry; and 29th Connecticut Infantry in Ofcial Army

Register of the Volunteer Force of the United States Army, 8 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Adjutant

General’s Ofce, 1867), vol. 8.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

424

which it would not do for ofcers’ wives. Although this solution might work

for soldiers whose wives were already close by, it clearly would not help those

whose families were in Maryland or the North.

106

When the order to prepare for a move reached the troops, rumors bur-

geoned. Early in 1863, when the 1st South Carolina Volunteers received orders

for Florida, stories circulated that the men would be sold into Cuban slavery to

raise money for the war. This time, rumor had it that the men of the XXV Corps

would go south to pick cotton until the war was paid for. Ofcers assured their

men that it was not so, but many remained suspicious. Nevertheless, few de-

serted before boarding the transports, and only a handful of incidents occurred

that amounted to mutiny.

107

Embarkation began on 25 May and ended at noon on 7 June, when the

transport with General Weitzel and his staff aboard weighed anchor. Unlike the

responsibilities that faced the Union force in most of the occupied South, those

of the XXV Corps in southern Texas had less to do with the reestablishment

of civil government and protection of the rights of new black United States

citizens than with international diplomacy and simple law enforcement. During

the war, the regiments that belonged to the corps had spent periods that varied

from four months to eighteen months in Virginia, the least typical theater of

operations in the South. Before they mustered out, they would serve for similar

periods in the most unusual region of the postwar occupation—the Rio Grande

border with Mexico.

106

Maj Gen E. O. C. Ord to Brig Gen G. H. Gordon, 12 May 1865, Entry 5046, pt. 2, RG 393,

NA. For the 114th USCI, see W. Goodale to Dear Children, 20 Apr 1865, W. Goodale Papers,

Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston; Berlin et al., Black Military Experience, pp. 656–61;

Wiley, Life of Billy Yank, pp. 49, 291–92. Miller, Black Civil War Soldiers of Illinois, pp. 153–54,

offers a good, brief summary of morale in the XXV Corps in May 1865.

107

OR, ser. 1, vol. 46, pt. 3, p. 1262; Berlin et al., Black Military Experience, pp. 723–27;

Glatthaar, Forged in Battle, p. 219; Miller, Black Civil War Soldiers of Illinois, p. 153. For the rumor

about black soldiers being sold in Cuba, see Chapter 1, above.

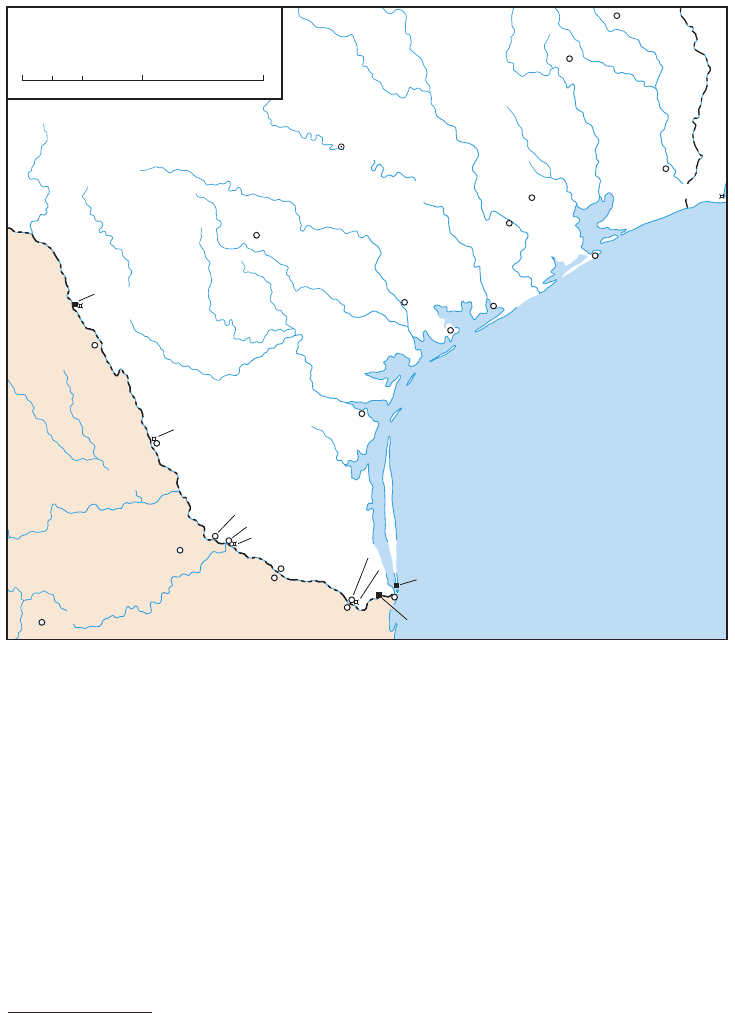

When the Republic of Texas joined the United States in 1845, its admission

to the union allowed President James K. Polk to move an American army into the

southern tip of the new state, past the Nueces River and all the way to the Rio

Grande. Since Mexico had disputed Texan claims to the region south of the Nueces

throughout the ten years since Texas had achieved its independence, Polk’s aggres-

sive maneuver plunged the United States and Mexico into war. The Treaty of Gua-

dalupe Hidalgo ended the conict ofcially in early 1848, xing the international

boundary and the southern edge of Texas on the Rio Grande (see Map 9).

1

Slaves in Texas were few along the international boundary but more numer-

ous farther north in river valleys where cotton and sugar cultivation made “the

institution” protable. These staple crops left the state by way of its main seaport,

Galveston, which also served as a landing place for thousands of immigrants each

year. Galveston and its inland neighbor Houston together numbered more than

twelve thousand residents, black and white, in 1860. Farther south, on Matagorda

Bay, lay the state’s second seaport, Indianola, with some eleven hundred inhabit-

ants. Only 357 of the state’s 182,921 black residents lived south of the Nueces

River in a semiarid land where range cattle outnumbered people by at least ten to

one. More than one-third of this region’s black residents were free, a sharp contrast

with the rest of Texas. Fifty-three free men and women and only seven slaves lived

in Brownsville, a border town some twenty miles up the Rio Grande from the Gulf

of Mexico.

2

Brownsville and other towns along the lower Rio Grande continued to grow

during the years after the Mexican War. As merchants and ranchers from the

United States arrived in the region, they wrested economic and political power

from native Spanish-speakers. This ethnic conict occasionally erupted in gunre,

as during the “Merchants War” of 1851, which concerned trade; the “Cart War”

of 1857, touched off by freight rates; and, most serious, the “Cortina War” of

1859, occasioned by ill will between Spanish-speaking Tejanos and the ascendant

1

K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War, 1846–1848 (New York: Macmillan, 1974), pp. 4–7, 11–12,

17–21, 28–29.

2

U.S. Census Bureau, Population of the United States in 1860 (Washington, D.C.: Government

Printing Ofce, 1864), pp. 484–87, and Agriculture of the United States in 1860 (Washington, D.C.:

Government Printing Ofce, 1864), pp. 140, 144, 148; Daniel D. Arreola, Tejano South Texas: A

Mexican American Cultural Province (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002), pp. 11–19.

South Texas, 1864–1867

Chapter 13

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

426

English-speaking Texans. Although this last outbreak, named for the landowner

Juan N. Cortina, involved only a few dozen men on each side, United States troops

had to quell the disturbance. Despite these violent episodes, Brownsville thrived

during the 1850s. By the end of the decade, its 2,347 residents made it the fth-

largest city in Texas.

3

On 2 February 1861, thirteen years to the day after diplomatic representatives

of the United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the state

of Texas adopted an ordinance of secession from the Union. First on its list of

grievances were Northern schemes to abolish “the institution known as negro slav-

ery.” With that, the Rio Grande became the Confederacy’s only land frontier with

3

Census Bureau, Population of the United States in 1860, pp. 486–87; Benjamin H. Johnson,

Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans into

Americans (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), pp. 10–25; David Montejano, Anglos and

Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987), pp. 26–33;

Jerry Thompson, Cortina: Defending the Mexican Name in Texas (College Station: Texas A&M

University Press, 2007), pp. 22–23, 35.

An 1859 map shows the central position of Kentucky between two future Confederate

states, Tennessee and Virginia, and four that remained in the Union, Ohio, Indiana,

Illinois, and Missouri. Lincoln is reputed (but not proven) to have quipped, “I hope to

have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.”

C

o

l

o

r

a

d

o

R

B

r

a

z

o

s

R

N

u

e

c

e

s

R

M

a

t

a

g

o

r

d

a

B

a

y

G

a

l

v

e

s

t

o

n

B

a

y

R

i

o

G

r

a

n

d

e

T

r

i

n

i

t

y

R

S

a

b

i

n

e

R

GULF OF MEXICO

Brazos Santiago

Palmetto Ranch

Eagle Pass

Isla del Padre

Fort Duncan

Fort McIntosh

Ringgold Barracks

Fort Brown

Fort Sabine

Victoria

Indianola

Matagorda

Trinity

Richmond

Nacogdoches

Reynosa

Edinburg

Roma

Mier

Rio Grande City

Laredo

Presidio del

Rio Grande

Monterey

Bagdad

San Antonio

Corpus Christi

Brownsville

Matamoros

Houston

Galveston

Beaumont

AUSTIN

TEXAS

MEXICO

LOUISIANA

SOUTH TEXAS

1864–1867

0

160804020

Miles

Map 9

South Texas, 1864–1867

427

a neutral country. Shipping boomed, with wagons carrying baled cotton across the

forbidding landscape of southern Texas to pay for munitions of war that entered

Mexican seaports. One merchant in England delivered forty-two hundred Eneld

ries for $24.20 each, for which he expected payment in cotton at thirty cents a

pound: in all, more than fteen tons of cotton. In the course of the war, as many as

three hundred fty thousand bales may have left the Confederacy by crossing the

Rio Grande. The Mexican town of Matamoros, opposite Brownsville, swelled to a

population of some forty thousand. Its seaport, Bagdad, also thrived.

4

A few weeks before Texas left the Union, rival Mexican parties known as Lib-

erals and Conservatives concluded a civil war of their own that had lasted for

more than two years. At issue was the constitution of 1857, a secular document fa-

vored by the Liberals that, among its other provisions, disestablished the Catholic

Church. Guerrilla warfare, massacres, and reprisals characterized the conict. By

the time the Liberals won, the country lay exhausted. An empty treasury caused

Benito Juárez, the new president, to suspend repayment of Mexico’s foreign loans.

This prompted the creditor nations, Britain, France, and Spain, to take direct ac-

tion. In December 1861, a naval eet from the three powers landed troops at Ve-

racruz and occupied the port. When Britain and Spain learned a few months later

that the French emperor, Napoleon III, intended to conquer the entire country and

install a puppet government, they withdrew their contingents. Lacking the legiti-

macy conferred by prominent allies, French troops nevertheless marched inland,

meeting erce resistance that blocked their path to Mexico City for a year and a

4

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Ofcial Records of the Union and Confederate

Armies, 70 vols. in 128 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1880–1901), ser. 4, 3: 569–

70, 572–74 (hereafter cited as OR); Ernest W. Winkler, ed., Journal of the Secession Convention

of Texas, 1861 (Austin: Texas Library and Historical Commission, 1912), pp. 61–66 (quotation, p.

62); David G. Surdam, Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the American Civil War

(Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001), p. 178; Jerry Thompson and Lawrence T.

Jones III, Civil War and Revolution on the Rio Grande Frontier: A Narrative and Photographic

History (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 2004), p. 17; Stephen A. Townsend, The Yankee

Invasion of Texas (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2006), pp. 5–7.

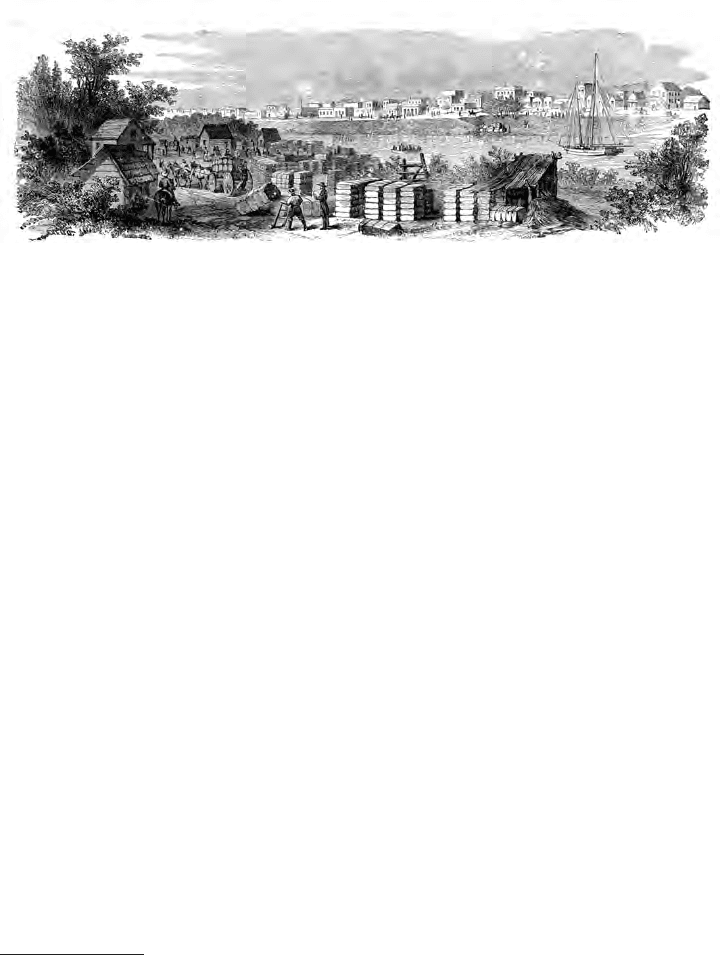

Brownsville, Texas, from across the Rio Grande. The bales of cotton stacked on the

Mexican shore indicate Brownsville’s economic importance to the Confederacy.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

428

half. Archduke Maximilian of Austria, a relative of Napoleon’s by marriage, ar-

rived in the spring of 1864 to ascend the throne as emperor of Mexico.

5

In order to forestall French occupation of the mouth of the Rio Grande and to

stop the trafc in military stores and cotton, the Union’s Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P.

Banks dispatched a force from the Department of the Gulf to seize the lower river

in the fall of 1863. On 6 November, federal troops raised the United States ag

over Brownsville for the rst time since March 1861. The few hundred Confeder-

ates in the region withdrew north of the Nueces River, or up the Rio Grande toward

Eagle Pass. As they moved upriver, the route of Southern cotton for export had to

shift westward more than three hundred miles, adding further expense to already

heavy freight costs. With two contending parties, Union and Confederate, on the

north side of the river and two, the Liberals (Juárez) and the Imperialists (Maximil-

ian), on the south, the lower Rio Grande soon attracted a class of men whose ethics

were elastic, often in the extreme.

6

Events far from the Rio Grande valley also had a decisive inuence on Union

operations there, the kind of effect that outlying military departments on both sides

of the conict felt throughout the war. The failure of General Banks’ Red River

Expedition in the spring of 1864 and the withdrawal that summer of the XIX Corps

from Louisiana to Virginia led to the abandonment of all but one of the federal

beachheads in Texas in order to reinforce garrisons along the Mississippi River.

Texas and its cotton were alluring targets for a Union expedition, but the agricul-

ture and commerce of a dozen loyal states, from western Pennsylvania to Kansas,

depended on federal control of the Mississippi.

7

As Union troops withdrew from the Texas coast, a Confederate force reentered

Brownsville on 30 July, once again affording cotton shipments a short but still

arduous route to Mexico. Only the federal post at Brazos Santiago, near the mouth

of the Rio Grande, remained. It was a secure position on an island, approachable

from the mainland by only one route. In the fall of 1864, four regiments constituted

the garrison: the 91st Illinois and the 62d, 87th, and 95th United States Colored

Infantries (USCIs). The 62d had begun its existence as the 1st Missouri Colored

Infantry, organized near St. Louis in December 1863. The 87th and 95th USCIs

were Louisiana regiments, raised in and around New Orleans as part of General

Banks’ Corps d’Afrique.

8

At the beginning of November 1864, a new commanding general arrived at

Brazos Santiago: Brig. Gen. William A. Pile, who had helped Adjutant General

Lorenzo Thomas recruit black troops, including the 1st Missouri Colored Infantry,

5

Enrique Krause, Mexico: Biography of Power: A History of Modern Mexico, 1810–1996 (New

York: HarperCollins, 1997), pp. 169–74; Paul Vanderwood, “Betterment for Whom? The Reform

Period, 1855–1875,” pp. 371–96 in The Oxford History of Mexico, eds. Michael C. Meyer and

William H. Beezley (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), especially pp. 375–83.

6

Surdam, Northern Naval Superiority, p. 177; Townsend, Yankee Invasion of Texas, pp. 14–19;

Ronnie C. Tyler, “Cotton on the Border, 1861–1865,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 73 (1970):

461–63. Examples of rascality on both sides of the border in early 1864 are in OR, ser. 1, vol. 34, pt.

2, pp. 8–10, 216–17.

7

Stephen A. Dupree, Planting the Union Flag in Texas: The Campaigns of Major General

Nathaniel P. Banks in the West (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2008), pp. 6–7.

8

OR, ser. 1, vol. 41, pt. 1, pp. 185–86, and pt. 4, pp. 266–67, 366; Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium

of the War of the Rebellion (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1959 [1908]), pp. 1718–19, 1733, 1736–37.

South Texas, 1864–1867

429

a year earlier. Pile found conditions at Brazos Santiago far from satisfactory and

blamed his predecessor in command, the colonel of the 91st Illinois. The previous

ordnance ofcer, Pile reported, had been “inefcient and negligent. In this he took

pattern from the Comdg Ofcer of these Forces. The whole command except the

62d USCI (just arrived) being without discipline . . . and performing their duties

very inefciently.” The garrison lacked a shallow-draft boat for travel along the

coast; its horses were “broken down and diseased,” left behind by the expedition

that had seized the island a year earlier; hospital patients lay in tents that were often

blown down and shredded by squalls from the Gulf of Mexico; the commissary

ofcer sold Army beef to civilians; the quartermaster provided passage to New

Orleans on government steamers for civilians who paid in gold. Pile set to work at

once to clean house.

9

He ought to have known better than to expect that any supplies he requested,

such as lumber to build a windbreak for the hospital tents, would come at once to

a backwater outpost like Brazos Santiago. After a month on the island, Pile asked

for another infantry regiment to replace the 91st Illinois and additions of cavalry

and heavy artillery to his command. “If I had 500 cavalry I could inict material

damage” on the Confederates at Brownsville, he wrote to Department of the Gulf

headquarters in New Orleans. “Is it desired that I do anything on the mainland? I

would like to take a command to Brownsville, if it is the intention of the military

authorities to occupy this coast; if not, I desire to be transferred to another com-

mand.” Pile’s letter passed on to even higher headquarters, the Military Division

of West Mississippi. There, Maj. Gen. Edward R. S. Canby remarked that “the

rst duty of an ofcer is to do the best he can with the means at his command, and

not to ask to be relieved because his superior ofcers may nd it impracticable or

inexpedient to increase his resources.”

10

Despite Canby’s rebuke, Pile received a few things he had asked for. On 26

November, in one of the consolidations that befell understrength Louisiana regi-

ments, the enlisted men of the 95th merged with those of the 87th. The new orga-

nization at rst received the number 81, until word arrived that there was already a

regiment of that number. Since the consolidation had left the number 87 vacant, the

new regiment became the 87th USCI (New). Slow communications and conicting

regional authorities ensured that such confusion occurred repeatedly throughout

the war. The decision to discharge nearly three-quarters of the ofcers of the old

87th and 95th, retaining only fourteen of the forty-eight, seemed to conrm Pile’s

assessment of their aptitude. Late in December, the 91st Illinois left Brazos San-

tiago for New Orleans, trading places with the 34th Indiana.

11

Pile got another of his wishes in February 1865, when he received orders to

join General Canby’s expedition against Mobile. Arriving in New Orleans, he re-

quested the assignment of two regiments to the expedition: the 81st USCI, which

9

OR, ser. 1, vol. 41, pt. 4, pp. 448–49, 676 (“broken down”); Brig Gen W. A. Pile to Maj G. B.

Drake, 28 Nov 1864 (“inefcient and”), Entry 5515, Mil Div of West Mississippi, Letters Received

(LR), pt. 1, Geographical Divs and Depts, Record Group (RG) 393, Rcds of U.S. Army Continental

Cmds, National Archives (NA).

10

OR, ser. 1, vol. 41, pt. 4, pp. 767–68.

11

Dyer, Compendium, pp. 1085, 1133, 1737; Ofcial Army Register of the Volunteer Force of

the United States Army, 8 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Adjutant General’s Ofce, 1867), 8: 267–68, 276

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

430

he had recently inspected at Port Hudson and thought was “perhaps the best col-

ored regiment in this department,” and the 62d USCI at Brazos Santiago, “also a

well drilled and disciplined regiment and well tted for eld service.” He asked

that they be sent “if necessary, in the place of other regiments not in so good condi-

tion, and that one of [them] be assigned to my brigade.” Such praise came not from

a politician or newspaper correspondent, nor from a politically appointed major

general at the head of a geographical department, but from a brigadier seeking to

improve his own command with troops whose performance could make or mar

his reputation and perhaps even cost him his life. This time, authorities refused to

grant even part of Pile’s request. The two regiments he asked for remained at their

stations in Louisiana and Texas while Pile and his brigade set off for Mobile on the

last major campaign of the war.

12

The 62d USCI spent the winter on Brazos Santiago. Its commanding ofcer,

Lt. Col. David Branson, took measures to maintain and improve regimental disci-

pline and morale. He admonished “several ofcers” of the regiment for hitting the

men with their sts or the at of a sword. “An ofcer is not t to command who

cannot control his temper sufciently to avoid the habitual application of blows

to enforce obedience,” he wrote. “Men will not obey as promptly an ofcer who

adopts the systems of the slave driver to maintain authority as they will him who

punishes by a system consistent with . . . the spirit of the age.” Branson allowed

that “generally, the men who have received such punishment have been of the

meanest type of soldiers; lazy, dirty & inefcient.” Still, he insisted, “such treat-

ment will not produce reform in them, while it has an injurious effect on all good

men, from its resemblance to their former treatment while slaves.” By mid-April,

Branson reported the regiment “in a good state of discipline [and] in excellent

health,” while having “attained an unusual degree of efciency in Battalion Drill

and in the Bayonet Exercise.” He asked for 437 recruits to augment the 543 men

that remained of the 1,050 who had entered the ranks of the regiment during its

sixteen months of service. Eighty-six of the missing men had died of disease be-

fore they left Missouri. More than two hundred lay buried at Port Hudson and Mor-

ganza, Louisiana, where the health of the regiment had suffered severely. Scores

more had died elsewhere in the state.

13

In April 1865, news of the Confederate surrender in Virginia traveled by tele-

graph, reaching St. Louis within twenty-four hours. Separated from the telegraph

by miles of enemy-held territory, soldiers at Union beachheads on the Gulf of

Mexico received that news, and word of the surrender in North Carolina, a week

or more later. While Confederate generals in Alabama made similar arrangements,

those west of the Mississippi River considered their situation. Maj. Gen. John B.

(hereafter cited as ORVF). For the organization, consolidation, and disbandment of Corps d’Afrique

regiments, see Chapters 3 and 4, above.

12

OR, ser. 1, vol. 48, pt. 1, pp. 846, 964 (quotations).

13

62d United States Colored Infantry (USCI), General Orders (GO) 36, 9 Nov 1864; Lt Col D.

Branson to Adj Gen, USA, 20 Apr 1865; Company Descriptive Books; all in 62d USCI, Regimental

Books, RG 94, Rcds of the Adjutant General’s Ofce (AGO), NA. NA Microlm Pub M594,

Compiled Rcds Showing Svc of Mil Units in Volunteer Union Organizations, roll 212, 62d USCI;

Ira Berlin et al., eds., The Black Military Experience (New York: Cambridge University Press,

1982), pp. 513–14; Margaret Humphreys, Intensely Human: The Health of the Black Soldier in the

American Civil War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), pp. 116–17.