Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

401

medicine, and other supplies—that entered the Confederacy between Novem-

ber 1863 and October 1864.

50

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles had long urged an expedition to re-

duce Fort Fisher and capture Wilmington. By mid-September, Grant had ac-

ceded to the idea, but attacks on Richmond and Petersburg remained upper-

most in his mind. Days after the second attack failed in late October, General

Butler was under orders for New York City with more than six thousand troops

to keep order there during the presidential election. When he returned, Colonel

Pierson’s prediction about the weather had come true: “Roads nearly impass-

able,” Butler wrote to Grant, who had himself gone north for a few days.

51

As the troops waited for the roads to dry, it became time to implement an

administrative change that had been under consideration for months. A few

weeks after the IX Corps defeat at the Petersburg Crater that summer, Butler

had suggested to Grant that Ferrero’s division and its nine black regiments

should transfer from Meade’s Army of the Potomac to his own Army of the

James. “From all that I can hear the colored troops . . . have been very much

demoralized by loss of ofcers and by their repulse of [July] 30th,” he wrote,

adding the next day: “If they could be sent to me, . . . they might be recruited up

and got into condition.” Grant replied that at that time every one of his soldiers

was occupied, either holding the trenches or preparing an offensive move. Not

until mid-November did he consider the pace of events slow enough to make

the change.

52

The reorganization turned out to be more profound than the movement of

nine regiments from Meade’s army to Butler’s authorized on 25 November.

Eight days later came an order discontinuing the X and XVIII Corps. The white

infantry divisions of those commands would constitute the XXIV Corps; the

three black divisions, the XXV Corps. At the head of the XXV Corps was Maj.

Gen. Godfrey Weitzel, the same ofcer who had asked Butler to remove black

troops from his command in Louisiana more than two years earlier. Whether

it was because of the hard campaigning that black soldiers had done since his

complaint or because of his accession to a second star and with it command of

a corps rather than the brigade that he had led in Louisiana, Weitzel voiced no

qualms when he took command of the largest organization of black soldiers in

the war (Table 2).

53

One of the regiments that joined Butler’s command was the 30th USCI.

“General Meade had agreed with Gen Butler to trade us off for white troops,”

Colonel Bates wrote. “I am glad of it for I have always thought the colored

troops ought to be placed together, and under Butler there is no doubt but that

50

Robert M. Browning Jr., From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading

Squadron During the Civil War (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1993), pp. 220, 228–29,

266–68; McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, pp. 380–82.

51

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 364–65; vol. 42, pt. 3, pp. 492, 503–04, 517, 638, 669 (quotation).

John G. Barrett, The Civil War in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

1963), pp. 262–63.

52

OR, ser. 1, vol. 42, pt. 2, pp. 323 (“From all”), 349 (“If they”), 350, and pt. 3, p. 619.

53

OR, ser. 1, vol. 42, pt. 3, pp. 702, 791. For Weitzel in Louisiana, see Chapter 3, above; his 1862

letter to Butler is in OR, ser. 1, 15: 171–72.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

402

they will have credit for all they do.” A major general leading an entire corps

of black soldiers could keep them from being assigned chores that would fall to

civilian employees of the Quartermaster Department. A commander of a single

black regiment in an otherwise all-white brigade could offer his men no such

protection.

54

While the troops were moving to new camps and becoming acquainted,

Grant wrote to Butler, urging the importance of the move against Wilmington.

The last week of November brought news, via Augusta and Savannah news-

papers, that the Confederate General Braxton Bragg had left Wilmington to

oppose Sherman’s march through Georgia. Bragg had taken with him “most of

54

D. Bates to Father, 20 Nov 1864, Bates Letters.

Table 2—XXV Corps Order of Battle, 3 December 1864

XXV Corps (Maj. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel)

1st Division (Brig. Gen. Charles J. Paine)

1st Brigade (Bvt. Brig. Gen. Delavan Bates)—1st, 27th, and 30th USCIs

2d Brigade (Col. John W. Ames)—4th, 6th, and 39th USCIs

3d Brigade (Col. Elias Wright)—5th, 10th, 37th, and 107th USCIs

2d Division (Brig. Gen. William Birney)

1st Brigade (Bvt. Brig. Gen. Charles S. Russell)—7th, 109th, 116th, and 117th USCIs

2d Brigade (Col. Ulysses Doubleday)—8th, 45th (six companies), and 127th USCIs

3d Brigade (Col. Henry C. Ward)—28th, 29th, and 31st USCIs

3d Division (Brig. Gen. Edward A. Wild)

1st Brigade (Bvt. Brig. Gen. Alonzo G. Draper)—22d, 36th, 38th, and 118th USCIs

2d Brigade (Col. Edward Martindale)—29th Connecticut; 9th and 41st USCIs

3d Brigade (Brig. Gen. Henry G. Thomas)—19th, 23d, and 43d USCIs

USCC = United States Colored Cavalry; USCI = United States Colored Infantry.

Note: The 2d USCC was in the corps but not assigned to a brigade; the ten artillery batter-

ies in the XXV Corps were white. Companies of the 1st USCC and Battery B, 2d U.S. Colored

Artillery, were at Newport News, Norfolk, Portsmouth, and posts along the James River.

Source: The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Ofcial Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1880–

1901), ser. 1, vol. 42, pt. 3, pp. 791, 1126–29 (hereafter cited as OR).

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

403

the troops” in garrison there, Grant told Butler. Four days later, he expressed

“great anxiety to see the Wilmington expedition off.”

55

One element remained to be added to the campaign: Butler himself decided to

go along. In January 1865, he testied before the Joint Committee on the Conduct of

the War that he did not trust Weitzel because of his youth. The 29-year-old West Point

graduate had led brigades and divisions in the eld for two years; Butler had spent

half of that period at home, between his administrative commands in Louisiana and

Virginia, awaiting assignment. Although Butler’s attempt to direct the work of another

eld commander, Maj. Gen. William F. Smith, on the James River earlier that year had

ended badly, Grant approved the arrangement and Butler accompanied the expedition to

Wilmington. Grant testied later that he had “never dreamed of [Butler’s] going” until

the expedition was under way; he had merely transmitted orders to Weitzel through But-

ler as the senior general commanding the geographical department where the younger

man was to operate.

56

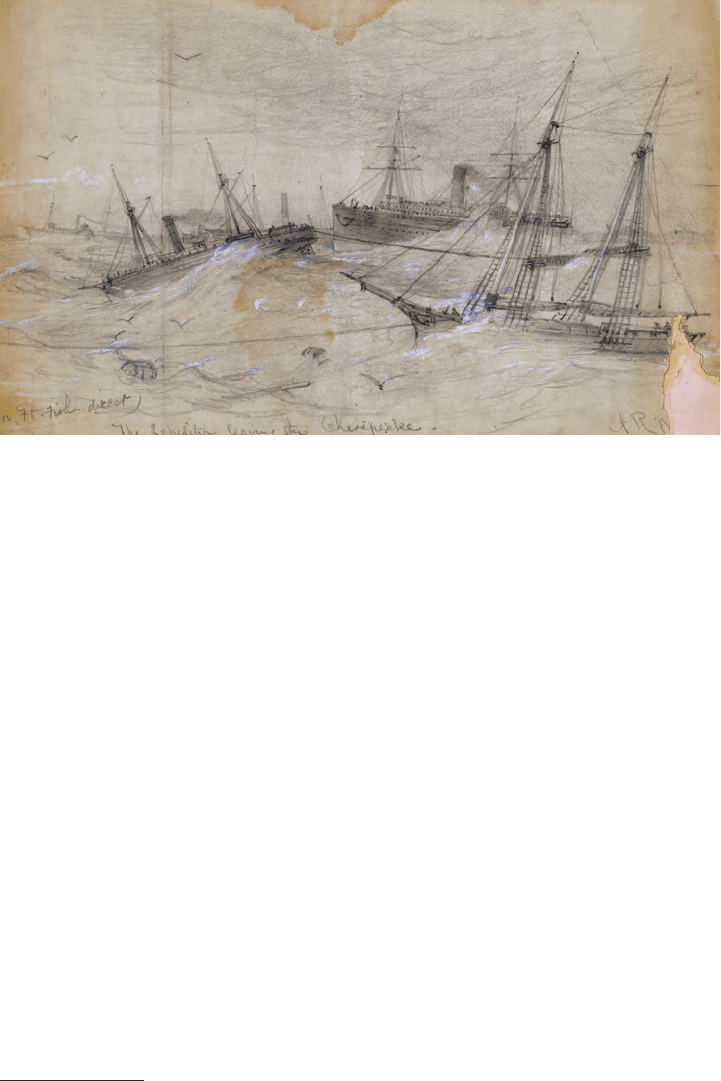

Although Butler and the senior naval ofcer in the region, Rear Adm. David D.

Porter, had grown to detest each other during their service in Louisiana two years earlier,

both men saw the end of the war approaching and wanted to nish their roles in it with a

resounding victory. Butler directed Weitzel to tell General Paine of the XXV Corps and

one division commander from the XXIV Corps to “select their best men” for a force of

6,500 infantry, 50 cavalry, and 2 batteries of artillery. For Paine’s all-black division, this

meant leaving behind 25 percent of its strength, the least t of its one hundred sixty of-

cers and forty-one hundred men. While their leaders tried to complete arrangements, the

chosen troops boarded transports at Bermuda Hundred on 8 December. The next day,

they oated downstream to Fort Monroe, where they waited. By 14 December, when the

expedition nally steamed south, knowledge of its destination had spread throughout

the eet. “The other vessels . . . with their designating lights of blue and white ash-

ing and dancing with the modulations of the waves, formed a beautiful scene,” 1st Lt.

Joseph J. Scroggs of the 5th USCI observed. “Plenty of pitch but not sick,” Sergeant

Major Fleetwood recorded in his diary. He, Scroggs, and about thirty-two hundred other

members of Paine’s division stayed aboard ship for the next eleven days.

57

The troops waited at sea while Butler, the amateur general, carried out a pet scheme.

He planned to destroy Fort Fisher with an enormous explosive charge, seventy-ve times

the size of the one used at Petersburg in July. Instead of tunneling under the Confeder-

ate works, he hoped to use a condemned vessel to oat three hundred tons of powder

within half a mile of the fort. After the explosion, his troops would walk into the ruins

and accept the surrender of any survivors. As it turned out, the charge failed to detonate

properly on 23 December and did no damage to Fort Fisher. Grant afterward derided

the idea, referring to it as “the gunpowder plot,” after the failed seventeenth-century

55

OR, ser. 1, vol. 42, pt. 3, pp. 760 (“most of the”), 799 (“great anxiety”).

56

Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, 9 vols. (Wilmington, N.C.:

Broadfoot Publishing, 1998) [1863–1865], 5: 11, 52 (quotation).

57

OR, ser. 1, vol. 42, pt. 3, p. 837 (“select their”); 3d Div, XVIII Corps, Field Return, 4 Dec 1864,

Entry 1659, pt. 2, RG 393, NA; J. J. Scroggs Diary, 8 and 14 (quotation) Dec 1864, MHI; Fleetwood Diary;

Chester G. Hearn, Admiral David Dixon Porter (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1996), pp. 116–17, 274;

Hans L. Trefousse, Ben Butler: The South Called Him Beast! (New York: Twayne, 1957), pp. 124, 170.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

404

conspiracy to blow up the English parliament. He told congressional investigators that

he approved the idea only because the Navy seemed to be interested in it, too.

58

At last, on Christmas Day, Butler’s expedition put a small landing force ashore.

Men of both divisions took part. “Co. ‘H’ [of the 5th USCI] was ordered into the launch-

es,” Scroggs wrote.

We landed amid a shower of bullets from the enemy concealed in the bushes skirting

the shore, deployed and advanced, a few well directed shots scattering the Johnnies like

chaff. In the meantime the White troops had landed farther down the beach and a small

party of 60 rebs had surrendered to them. . . . [Brig. Gen. N. Martin] Curtis was about

making an assault on the main works when he received Butler’s order to fall back. The

fort was weakly defended and could have easily been taken but the order had to be

obeyed and we all fell back to the beach. . . . We were all on board the transports again

shortly after dark and heading seaward.

Sergeant Major Fleetwood spent the afternoon between the transports and the shore.

“Got three companies off and ordered back,” he entered in his diary. “Got a drenching

in the surf coming off.” The eet steamed north to the James River and deposited the

58

Report of the Joint Committee, 5: 51 (quotation); Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape

Fear, pp. 288–89; Longacre, Army of Amateurs, p. 237.

Union transports in a heavy sea, en route to attack Wilmington, North Carolina. “Plenty

of pitch but not sick,” Sgt. Maj. Christian A. Fleetwood wrote in his diary.

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

405

troops there during the last week of the year. “Probably we will be permitted to hibernate

unmolested the remainder of the winter,” Lieutenant Scroggs wrote. “Hope so.”

59

In defense of his decision to withdraw the troops despite specic instructions to

establish a permanent beachhead at Fort Fisher, Butler pleaded that he had sought to

avoid a repetition of the horrendous repulses of Union assaults on Port Hudson and Fort

Wagner eighteen months earlier. The president relieved him on 7 January 1865. With the

election won and another four years in ofce to look forward to, Lincoln had no further

need to conciliate Butler or to tolerate any more of his attempts at military leadership.

Maj. Gen. Edward O. C. Ord, former commander of the XXIV Corps, replaced Butler

as head of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina the next day. Maj. Gen. Alfred

H. Terry, previously a division commander, had already assumed responsibility for the

expedition to Fort Fisher.

60

Paine’s division boarded ships again on 5 January for what Captain Carter of the

staff told his wife was apt to be “another wild goose chase to Wilmington. . . . [S]

omebody is bound to get hurt this time for I don’t suppose that this expedition will be

given up if the last man should perish. . . . The season of the year and the character of the

coast where we are to operate . . . make me very uneasy for the result.” As it turned out,

the division suffered no casualties in the landing and fteen during the six days after.

61

The troops disembarked on 13 January. Paine’s division headed west across the

peninsula while the white troops and a force of marines and sailors turned south toward

the fort. The 5th and 37th USCIs led the way from the landing beach to the banks of the

Cape Fear River. There they began to dig a defensive line, using “bayonets, tin plates,

cups, boards & whatever would hold sand and rock,” wrote Capt. Henry H. Brown, pro-

moted from the adjutancy of the 29th Connecticut to lead a company in the 1st USCI,

“and in less than an hour a strong breast work [was] thrown up.” A relieving force of

some six thousand Confederates faced Paine’s division on 15 January during the assault

on Fort Fisher; but to the chagrin of its leaders, General Bragg, in overall command

of the defense of Wilmington, refused to order an all-out attack. “The pickets of my

division held their ground resolutely,” Paine reported. By evening Fort Fisher was in

Union hands. The attackers had taken more than two thousand prisoners and one hun-

dred sixty-nine cannon at a cost of six hundred fty-nine killed, wounded, and missing.

62

Sergeant Major Fleetwood wandered through the fort a few days later and viewed

the results of the seven-hour naval bombardment that had preceded the nal assault.

“Scarcely a square foot of ground without some fragment of unexploded shell,” he

told his father:

Heavy guns bursted, others knocked to pieces as though made of pipeclay, heavy gun

carriages knocked to splinters and dead bodies of rebels lying as they fell with wounds

horrible enough to sicken the beholder, some with half of their heads off, others cut

59

Scroggs Diary, 25 (“Co. ‘H’”) and 31 Dec 1864 (“Probably we”); Fleetwood Diary, 25

(quotation) and 28 Dec 1864; Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear, pp. 290–91; Longacre,

Army of Amateurs, pp. 249–53.

60

OR, ser. 1, vol. 42, pt. 1, pp. 968, 972; vol. 46, pt. 2, pp. 46, 60, 71.

61

OR, ser. 1, vol. 46, pt. 1, p. 424; S. A. Carter to My own darling Em, 3 Jan 1865, Carter Papers;

Scroggs Diary, 5 Jan 1865.

62

OR, ser. 1, vol. 46, pt. 1, pp. 399, 405, 423, 424 (quotation), 431; H. H. Brown to Dear Mother,

17 Jan 1865, Brown Papers; Barrett, Civil War in North Carolina, pp. 272, 279–80.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

406

in two, disemboweled and every possible horrible wound that could be inicted. Oh

this terrible war! . . . Yet we must go ahead somehow, and we will. . . . Ten blockade

runners have already walked quietly into our hands much to their surprise and disgust.

The blockade is now effectual.

Captain Carter, like many others, had been too close to the action to grasp its sig-

nicance. He wrote to his wife: “We have today just rec[eive]d papers . . . containing

the ac[coun]ts and are just beginning to nd out what we have done here. . . . I can

hardly realize that we have achieved so much with so slight a loss.”

63

The day after Fort Fisher fell, the Confederates abandoned their other forts

near the mouth of the river and withdrew some ten miles north to Fort Ander-

son, on the west bank. The force that had failed to relieve the besieged garrison

entrenched on the opposite bank. Together, they outnumbered Terry’s army. The

Union force, for its part, sat still for three weeks. “Nothing but sand, thicket and

swamp,” Fleetwood complained: “Can’t dig two feet under the surface without

striking water.” The men soon exhausted the sweet potatoes and cornmeal that they

had captured at Fort Fisher and had to survive on the basic army ration of hardtack,

coffee, beans, and salt pork, “with a rarity occasionally of fresh beef” and sh

from the river, Captain Brown wrote. As late as the last week in January, no sutlers

63

OR, ser. 1, vol. 46, pt. 1, p. 398; C. A. Fleetwood to Dear Pap, 21 Jan 1865, Fleetwood Papers;

S. A. Carter to My own precious wifey, 22 Jan 1865, Carter Papers.

Fort Fisher

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

407

had followed the troops to sell supplements to the monotonous diet. Reinforce-

ments and a new general arrived in the second week of February: Maj. Gen. John

M. Schoeld and a division of the XXIII Corps. Fifty days earlier, they had been

pursuing Hood’s ruined army south from Nashville. Since then, they had traveled

by rail and river steamer to Annapolis and taken ship there for North Carolina.

With one division of his corps landed and two more on the way, Schoeld ordered

a move toward Wilmington.

64

Schoeld’s instructions from Grant were to seize the city; prepare a supply

base for Sherman’s army, which was marching north from Savannah; and advance

to Goldsborough and the railroad there—the original objective of Burnside’s expe-

dition three years earlier. On 10 February, after ordering four hundred thousand ra-

tions and twenty thousand pairs of shoes for Sherman’s men, Schoeld instructed

his own troops to begin their advance the next morning. Terry’s force was to move

against the Confederates east of the river. “It is not expected to gain possession of

the enemy’s works,” Schoeld explained. “Nevertheless, if the demonstration de-

velops such weakness at any point of the enemy’s line as to indicate that an attack

would be successful it will be made at once.” The troops “started out with the idea

of taking up a new line of works and ascertaining the position of the enemy,” Cap-

tain Carter told his wife. “We ascertained that without much difculty,” he added

drily, “drove the rascals out of their rie pits back into their main line of works and

immediately threw up breastworks, in some places within 300 yards of their main

line.” It was “quite a nasty little ght,” Carter wrote, and cost the division ninety-

two killed and wounded.

65

The men of Paine’s division stayed in their new position across the river from

Fort Anderson, about twelve miles downstream from Wilmington, until the morn-

ing of 19 February, when they learned that the Confederate trenches opposite them

had emptied during the night. They moved forward that afternoon in cautious pur-

suit, meeting no resistance. The next morning, they began to exchange shots with

the enemy. About 3:00 p.m., they set eyes on the defenses of Wilmington, “an

earth-work well manned and showing artillery,” Paine reported. He ordered the 5th

USCI forward to reconnoiter.

66

Lieutenant Scroggs told the story somewhat differently. “Moved forward at

noon (the 5th still on the skirmish line),” he recorded in his diary, “and soon found

the enemys rear guard. Drove them before us until 3 P.M. when they fell behind a

strong line of works and refused to be driven further. Gen. Terry ordered the 5th to

charge the works and we done it, but were not able to take works manned by 4500

troops and mounted with six pcs. of artillery. . . . I suppose it was fun for Terry but

not for us.” The regiment lost fty-three ofcers and men killed and wounded.

67

Meanwhile, Union divisions on the other side of the river waded through a

swamp on the Confederates’ ank and routed them, continuing the pursuit the next

day. On the night of 21 February, Bragg’s remaining troops set re to the ships, bales

64

OR, ser. 1, vol. 46, pt. 2, p. 74; vol. 47, pt. 1, p. 909. Fleetwood to Dear Pap, 21 Jan 1865; H. H.

Brown to Dear Mother, 29 Jan 1865, Brown Papers; Barrett, Civil War in North Carolina, pp. 280–81.

65

OR, ser. 1, vol. 47, pt. 1, p. 925, and pt. 2, p. 384 (quotation); S. A. Carter to My own darling

Emily, 12 Feb 1865, Carter Papers.

66

OR, ser. 1, vol. 47, pt. 1, p. 925.

67

Ibid.; Scroggs Diary, 20 Feb 1865.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

408

of cotton, and military supplies that remained in Wilmington and evacuated the city.

As Paine’s division marched in the next morning, the city’s black residents rushed

to greet them. “Men and women, old and young, were running through the streets,

shouting and praising God,” Commissary Sergeant Norman B. Sterrett of the 39th

USCI wrote to the Christian Recorder. “We could then truly see what we had been

ghting for.” Captain Brown noticed “very few white people . . . as we came through

but the contrabands lled the streets & welcomed us by shouts of joy. ‘We’re free!

We’re free!’ ‘The chain is broke!’ &c. ‘This is my boy now’ said one old man as he

held his child by the hand.” The troops did not stop in the city, but pushed on an-

other ten miles before dark, securing a bridgehead on the Wilmington and Weldon

Railroad across the Northeast Branch of the Cape Fear River. There they waited for

supplies to reach Wilmington and for General Schoeld to gather a train of wagons

to move them inland.

68

The occupation of Wilmington presented Army ofcers, especially those of the

U.S. Colored Troops, with new opportunities and difculties. As occurred everywhere

in the South, the arrival of a Union Army attracted thousands of black residents from

the surrounding country. In February, the Subsistence Department issued rations to

7,521 black adults and 1,079 children at six sites along the North Carolina coast. Two

days after federal troops entered the city, the ofcer commanding the 6th USCI asked

permission to enlist one hundred twenty men to bring his regiment up to strength.

General Terry approved the request, and the regimental chaplain, one captain, and ve

enlisted men began recruiting. New men from North Carolina would provide useful

local knowledge for a newly arrived regiment that hailed from Philadelphia.

69

Less helpful was General Terry’s suggestion a few weeks later that he could

organize three new regiments among the black refugees gathered at Wilmington.

Union authorities were unprepared for the inux, as they so often were through-

out the war and in every part of the South. “They are pressing upon us severely,

exhausting our resources and threatening pestilence,” the district commander

complained. Terry proposed to use the refugees to strengthen Paine’s division,

which contained only ten regiments. Unfortunately for his plan, high-ranking

Union generals had known since 1862 that organizing new regiments was an

inefcient way to use recruits and that it was far better to put the new men in

existing regiments and let them learn by example from their comrades. Besides,

at this stage of the war, the last thing the Union army wanted was large masses of

untrained men who did not know their ofcers and whose ofcers did not know

them. Nothing came of Terry’s suggestion.

70

By 8 March, Sherman’s army was in North Carolina. He wrote to Terry in

Wilmington, saying that he would reach Fayetteville in three days and asking

for bread, sugar, and coffee. Terry sent as much as he could load in a shallow-

68

OR, ser. 1, vol. 47, pt. 1, pp. 911, 925, and pt. 2, pp. 559, 593–94, 619, 635–36, 654, 672, 683,

693–94; Christian Recorder, 1 April 1865; H. H. Brown to Dear Parents, 27 Feb 1865, Brown Papers.

69

Maj A. S. Boernstein to Capt A. N. Buckman, 24 Feb 1865 (B–42–DNC–1865), and

Endorsement, Capt W. L. Palmer, 15 Mar 1865, on Surgeon D. W. Hand to Maj J. A. Campbell, 7

Mar 1865 (H–65–DNC–1865), both in Entry 3290, Dept of North Carolina and Army of the Ohio,

LR, pt. 1, Geographical Divs and Depts, RG 393, NA.

70

OR, ser. 1, vol. 47, pt. 2, pp. 625, 978 (quotation); Maj Gen A. H. Terry to Lt Col J. A.

Campbell, 13 Mar 1865 (T–33–DNC–1865), Entry 3290, pt. 1, RG 393, NA. On leading Union

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

409

draft steamer up the Cape Fear River and prepared to march to meet Sherman at

Goldsborough. Paine’s division moved north, guarding what wagons Terry had

been able to collect and a mobile pontoon bridge that was necessary to cross

rain-swollen streams. Black residents along the route were no less enthusiastic

than those of Wilmington had been. “Some would clap their hands and say, ‘The

Yankees have come! The Yankees have come!’” Chaplain Henry M. Turner of the

1st USCI told readers of the Christian Recorder. “Others would say, ‘Are you

the Yankees?’ Upon our replying in the afrmative, they would roll their white

eyeballs up to heaven, and, in the most pathetic strain, would say, ‘Oh, Jesus,

you have answered my prayer at last! Thankee, thankee, Jesus.’ . . . Others would

commence venting their revengeful desires by telling of their hardships and the

cruelty of their owners, and wanting us to revenge them immediately.”

71

Occasionally, the tales of cruelty that slaves told soldiers had the desired effect.

Terry warned Paine of reports that “a portion of your command is burning buildings

and destroying property. . . . [W]hile proper foraging is not prohibited, . . . wanton

destruction cannot be permitted, and you will please take measures to put a stop to it

immediately.” Within a week of Terry’s letter, Chaplain Turner conrmed the charges

unofcially for readers of the Christian Recorder, relating an incident on the march

through North Carolina:

There was one infamous old rebel who . . . owned three hundred slaves, and

treated them like brutes. . . . Seeing his splendid mansion standing near the

road, our boys made for it, and soon learned that he had just released a colored

woman from irons, which had been kept on her for several days. Upon hearing

of this and sundry other overt acts of cruelty . . . , the boys grew incensed, and

they utterly destroyed every thing on the place. . . . With an axe they shattered

his piano, bureaus, side-boards, tore his nest carpet to pieces, and gave what

they did not destroy to his slaves—and on his speaking rather saucily to one

of the boys, he was sent headlong to the oor by a blow across the mouth. . . .

I heard afterward that the white soldiers burned his houses to the ground; but

whether they did so or not, I cannot say. But this much I do know—that I have

seen numbers of the nest houses turned into ashes.

Turner and other observers claimed that black soldiers learned burning and

looting from Sherman’s men, but most of the soldiers in Paine’s force had been

born and raised in slave states. Of the division’s regiments, the 1st USCI came

from Washington, D.C.; the 4th, 30th, and 39th from Maryland; the 10th from

Virginia; the 37th from North Carolina and Virginia; and the 107th from Ken-

tucky. Only the 5th, 6th, and 27th had been raised in the free states, and many

of the men in them had grown up in slavery. The advance into rebel territory

that had remained unscathed by the war—unlike the often fought-over part of

generals’ attitudes toward new regiments, see Maj Gen W. T. Sherman to Maj Gen U. S. Grant, 2

Jun 1863, in OR, ser. 1, vol. 24, pt. 3, pp. 372–73; Grant to the President, 19 Jun 1863, in OR, ser. 3,

3: 386; Maj Gen H. W. Halleck to Grant, 14 Jul 1863, in OR, ser. 3, 3: 487.

71

OR, ser. 1, vol. 47, pt. 2, pp. 735, 791, 819, 839–42; Christian Recorder, 15 April 1865.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

410

Virginia where they had served earlier—gave them, at last, a chance to exact

retribution.

72

Col. Giles W. Shurtleff, an Ohio abolitionist, tried to keep order in the 5th

USCI. “The plundering and pillaging have been fearful,” he told his wife.

The country is full of “foragers.” They have stripped everything from the people.

. . . Now I am not at all sure but the people merit this and it is perhaps the just

retribution of the Almighty. Still I believe it is cruel and wicked on the part of our

army. I have prevented this sort of action in my own regiment, and have gained the

ill will of many ofcers and men in doing so. While on the march, the men in the

regiments next to ours would break from the ranks and rush into houses and strip

them of every particle of provision. . . . I detailed men—placed them under an of-

cer and sent them to plantations away from the road with instructions to leave all

that was necessary for the subsistence of families. In this way I obtained all that

was necessary for my men and injured no one while I maintained the discipline

of my regiment.

Shurtleff was proud of his attempt to keep foraging from degenerating into robbery

and arson.

73

Late on 21 March, Paine’s division reached the Neuse River at Cox’s Bridge,

some ten miles west of Goldsborough. One brigade crossed the river that night and

entrenched; a second followed the next day. The XIV and XX Corps, half of Sher-

man’s army, came up the road from Fayetteville and crossed on the pontoon bridge

that Paine’s division had brought from Wilmington. Paine’s men had caught sight

of Sherman’s cavalry and foragers before, but not so large a body of infantry. It was

“a sight equally novel to both” forces, Turner wrote.

We all desired to see Sherman’s men, and they were anxious to see colored

soldiers. . . . [T]hey were not passing long before our boys thronged each side

of the road. There they had a full view of Sherman’s celebrated army. Soldiers

without shoes, ragged and dirty, came by thousands. Bronzed faces and tangled

hair were so common, that it was hard to tell if some were white. . . . Some of

their generals looked worse than our second lieutenants.

74

During the previous three days, Sherman’s men had driven General Joseph E.

Johnston’s Confederates back from Bentonville. The road to Goldsborough and

the railroad nally lay open. On 23 March, Sherman issued a congratulatory order

to his army, promising “rest and all the supplies that can be brought from the rich

granaries and store-houses of our magnicent country.” Active military operations

72

OR, ser. 1, vol. 47, pt. 2, pp. 625, 966 (Terry quotation); Christian Recorder, 15 April 1865.

For opinions of Sherman’s army, see Barrett, Civil War in North Carolina, pp. 293–300, 344–48;

Mark L. Bradley, This Astounding Close: The Road to Bennett Place (Chapel Hill: University of

North Carolina Press, 2000), pp. 26–28. On members of free-state regiments who were born in

slavery, see Paradis, Strike the Blow for Freedom, p. 112.

73

G. W. Shurtleff to My darling little Wife, 29 Mar 1864, G. W. Shurtleff Papers, OC.

74

OR, ser. 1, vol. 47, pt. 1, p. 925. NA M594, roll 205, 1st USCI; roll 206, 6th USCI; roll 208,

30th USCI; roll 209, 37th USCI; roll 215, 107th USCI. Christian Recorder, 15 April 1865.