Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The last state in which the Union recruited black troops was Kentucky. Stretch-

ing from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River, Kentucky touches

the boundaries of seven other states. Two of these, Tennessee and Virginia, had

joined the Confederacy; two others, Missouri and West Virginia, maintained slav-

ery but stayed in the Union; and three—Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio—were free

states. Kentucky’s neighbors, therefore, reached from Norfolk, Virginia, to St. Jo-

seph, Missouri; from Chattanooga to Chicago; from Cleveland to Memphis. North

or South, whichever side held Kentucky could strike at its opponent from several

different directions. For good reason then, Abraham Lincoln told a condant dur-

ing the rst autumn of the war: “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to

lose the whole game.”

1

The federal census of 1860 counted 38,645 slaveholding Kentuckians in the

state’s white population of 919,517. Their human property amounted to 225,483

persons. Slaves—and nearly all black Kentuckians were enslaved—accounted for

20 percent of the state’s population. Most of them lived in the fertile western and

central parts of the state, where production of grains, hemp, livestock, and tobacco

made their employment protable.

2

The sheer number of slaveholding whites in Kentucky—more than in any

other state but Virginia and Georgia—imposed extreme caution on Union poli-

cymakers during the early months of the war. The governor refused to answer

Lincoln’s call for militia in the spring of 1861, and the legislature declared

the state’s neutrality. Only in September, after a Confederate army fortied

Columbus, Kentucky, which commanded navigation on the Mississippi, did

federal troops cross the Ohio River and occupy towns at the mouths of the

Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers. Seven months later, they had moved up

both rivers, occupied Nashville, and beaten back attacking Confederates at

Pittsburg Landing, near the Mississippi state line. In October 1862, some of

1

William L. Miller, President Lincoln: The Duty of a Statesman (New York: Knopf, 2008), p.

110.

2

U.S. Census Bureau, Population of the United States in 1860 (Washington, D.C.: Government

Printing Ofce, 1864), p. 181, and Agriculture of the United States in 1860 (Washington, D.C.:

Government Printing Ofce, 1864), p. 229; Sam B. Hilliard, Atlas of Antebellum Southern

Agriculture (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1984), pp. 34, 36–38, 49–50, 52, 54, 59,

61–62, 66–67, 73–77.

Kentucky, North Carolina

and Virginia, 1864–1865

Chapter 12

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

382

the same troops ended the last major invasion of Kentucky when they defeated

a Confederate force at Perryville. Although mounted raiders remained active

until the end of the war, never again did they pose a signicant threat to Union

occupation of the state.

3

When federal troops abandoned their advanced posts in northern Alabama

during the fall of 1862 and hurried north to intercept the invasion of Kentucky,

they brought with them thousands of black refugees from slavery in parts of

the South that the Union could no longer hold. White Kentuckians leaped at

the chance to reenslave the new arrivals. Local authorities arrested those who

strayed too far from the protection offered by Northern soldiers, who by this

time in the war often practiced emancipation, even though they might disagree

with it in theory. In Kentucky, black people without passes faced jail and the

auction block. By April 1863, the military Department of the Ohio, which ad-

ministered all but the westernmost part of the state, had to issue an order on

3

Ira Berlin et al., eds., The Destruction of Slavery (New York: Cambridge University Press,

1985), p. 493; Richard M. McMurry, The Fourth Battle of Winchester: Toward a New Civil War

Paradigm (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2002), pp. 93–96; James M. McPherson, Battle

Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 516–22.

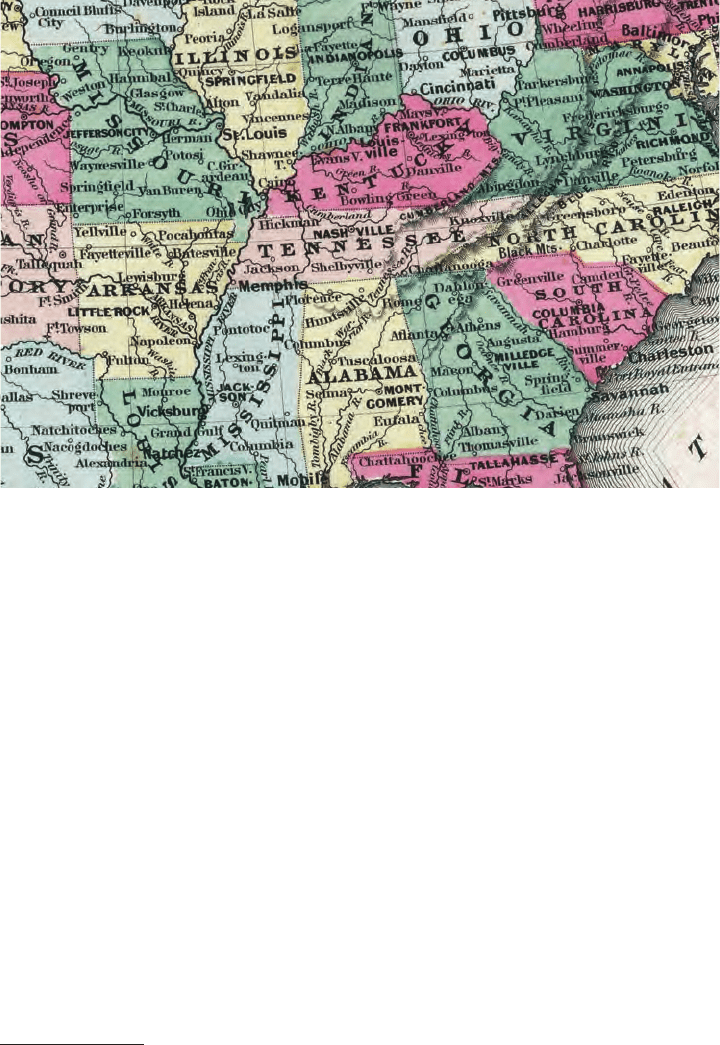

An 1859 map shows the central position of Kentucky between two future Confederate

states, Tennessee and Virginia, and four that remained in the Union, Ohio, Indiana,

Illinois, and Missouri. Lincoln is reputed (but not proven) to have quipped, “I hope to

have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.”

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

383

the subject and act to stop the abuse. Having found and freed for a second time

perhaps as many as a thousand of these former slaves, military authorities put

the adults among them to work, the men laboring on construction projects and

the women in army hospitals.

4

By early 1864, with a few dozen black regiments having already taken the eld

in other parts of the South, black Kentuckians’ contribution to the Union war effort

was still restricted to the role of civilian laborers, repairing roads between federal

garrisons in the state or laying track for the Louisville and Nashville Railroad.

Black men who wanted to enlist rst had to escape from bondage and then make

their way to the western tip of Kentucky, which lay in the Department of the Ten-

nessee, or leave the state altogether. More than two thousand of them went south to

Tennessee for that purpose. Others crossed the Ohio River to Northern states where

the War Department was also raising black regiments.

5

In the course of a trip to organize Colored Troops west of the Appalachians,

Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas had stopped for a few days in January at

Frankfort to confer with leading politicians. “My presence at the State capital

was the occasion of quite an excitement among all classes, male and female,”

he told Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, “the opinion being fully expressed

that I could only be there to take their negroes from them and put arms in their

hands.” Thomas suggested that since the state’s black men were enlisting in other

states and being credited toward the draft quotas of those states, Kentucky might

be well advised to raise a few black regiments of its own. The people he talked

to did not care for that idea but appeared less agitated by the end of his visit, he

told Stanton.

6

The Enrollment Act of 24 February 1864 changed everything. An amend-

ment to the act that had instituted conscription one year earlier, it specied that

male slaves, even those of loyal masters, for the rst time became eligible for the

draft. Opposition ared at once in Kentucky, even though the act did not propose

to take any slaves unless a state failed to meet its quota of white volunteers.

The most notorious display of disaffection came on 10 March, when Col. Frank

Wolford of the 1st Kentucky Cavalry addressed an audience that had gathered to

present him with an award for service to the Union cause, urging “the duty of the

people of Kentucky to resist” the measure. Two weeks later, Wolford received a

dishonorable discharge without a trial. The governor likewise advised forcible

resistance to the registration of slaves for the draft. He was about to issue a proc-

lamation to that effect but relented after an all-night conference with Brig. Gen.

Stephen G. Burbridge, who commanded the District of Kentucky. Meanwhile,

guerrillas continued to be active in many parts of the state, and in April raiders

4

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Ofcial Records of the Union and Confederate

Armies, 70 vols. in 128 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1880–1901), ser. 1, vol. 23,

pt. 2, p. 287 (hereafter cited as OR); Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The

End of Slavery in America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004), pp. 78–79; Ira Berlin et al., eds.,

The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor: The Upper South (New York: Cambridge University Press,

1993), pp. 628–30 (hereafter cited as WGFL: US).

5

OR, ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 2, p. 479; Ira Berlin et al., eds., The Black Military Experience (New

York: Cambridge University Press, 1982), pp. 191–92.

6

OR, ser. 3, 4: 60.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

384

led by Confederate Maj. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest penetrated as far north as Pa-

ducah, on the Ohio River, before returning south.

7

With so much controversy and turmoil, it is no wonder that the rst attempt

to enforce the February 1864 Enrollment Act in Kentucky failed. The next month,

more drafted men ignored or evaded the summons than answered it. General Bur-

bridge set to work to supply the decit. That he was a native Kentuckian and a slave-

holder typied Lincoln’s kid-glove approach to Kentucky, where three-quarters of

the Union troops in garrison belonged to regiments raised in the state. Despite his

local ties or any personal inclinations he may have had, Burbridge announced on

18 April that the War Department had named him superintendent of recruiting in

Kentucky and set forth the rules for enrolling black recruits: a slave could enlist

only with his owner’s consent; the owner would receive a certicate entitling him

to as much as four hundred dollars’ compensation for each slave enlisted. Once

sworn in, slaves would travel to a central depot at Louisville and from there “with

all possible dispatch” to “the nearest rendezvous or camp of instruction outside

of the State.” Burbridge repeated this provision in the last paragraph of the order.

Stanton called the repetition superuous but approved the rest of the order and di-

rected that Kentucky recruits go to Nashville, where Capt. Reuben D. Mussey was

organizing black regiments in the Department of the Cumberland.

8

In a state with Kentucky’s turbulent history during the previous three years,

the response of prospective black recruits to the federal initiative was quick and

enthusiastic. By the rst week in June, three hundred forty of them had reached

Mussey’s headquarters in Nashville, so many that he asked Stanton for authority

to increase the number of recruiters and to set up receiving centers in Kentucky

rather than ship recruits outside the state. A week later, Adjutant General Thomas

authorized the increase of recruiters and the establishment of eight camps, with

Camp Nelson, some twenty miles south of Lexington, receiving recruits from two

of the state’s nine congressional districts. Before the end of the month, General

Burbridge reported that ve regiments could be ready “in a very short time” if the

War Department would name the ofcers. According to Thomas, eighteen hundred

recruits had arrived at Louisville and Camp Nelson and awaited assignment to

regiments.

9

Many would-be volunteers headed for the nearest army camp without observ-

ing the legal requirement by obtaining their owners’ permission. Recruiting of-

cers accepted some of them, but those who could not pass the physical examination

and had to return home faced whippings and other physical punishment, including

mutilation. Moreover, the families of men who were able to convince recruiters to

accept them also found themselves facing ill treatment. Because of these “cruel-

7

OR, ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 3, pp. 88, 132–33, 146–47, 172–73, 418; ser. 3, 4: 132, 146, 174–75.

WGFL: US, p. 625; James W. Geary, We Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War (DeKalb:

Northern Illinois University Press, 1991), pp. 64, 130–31; Victor B. Howard, Black Liberation in

Kentucky: Emancipation and Freedom, 1862–1884 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky,

1983), pp. 57–62 (quotation, p. 58).

8

OR, ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 3, p. 572; ser. 3, 4: 132, 233–34 (quotations), 248–49. Howard, Black

Liberation in Kentucky, p. 63. An account of Mussey’s efforts in Tennessee is in Chapter 7, above.

9

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 2, p. 140 (quotation); ser. 3, 4: 423, 429–30, 460. Howard, Black

Liberation in Kentucky, pp. 65–67.

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

385

ties,” Burbridge was able to urge successfully, early in June, that recruiters be au-

thorized to accept any man who presented himself for enlistment. Those who were

not t for operations in the eld could perform garrison duty in an “invalid” regi-

ment composed of men with similar disabilities, like others in service elsewhere

in the South. The 63d and 64th United States Colored Infantries (USCIs) were

already guarding plantations along the Mississippi River, and the 42d and 100th

USCIs were performing guard and garrison duties at Chattanooga and Nashville.

10

Although the Army eventually set up camps to house soldiers’ dependents,

slaveholders’ abuse of the earliest recruits’ families slowed the pace of enlistment

during late spring. By summer, Burbridge found it necessary to send recruiting

parties through the state, as authorities in Tennessee had had to do a year earlier.

These groups faced active opposition. At Covington, across the Ohio River from

Cincinnati, the ofcer commanding the 117th USCI reported that a “small squad”

of his men led by a sergeant suffered one wounded and “several captured” in late

July. The next month, the size of recruiting parties had increased, by order, to no

fewer than fty men. An expedition through Shelby County, halfway between Lou-

isville and the state capital, required three hundred fty. Larger, well-armed parties

were better able to defend themselves against the “marauding Bands” mounted on

“eet Horses” that operated in most parts of Kentucky. Seventy men of the 108th

USCI routed a group of about sixty guerrillas northeast of Owensboro in mid-Au-

gust, wounding seven and capturing nine of them. Within three weeks, the ofcer

of the 118th USCI who commanded the garrison at Owensboro reported the mur-

der of three of his men by guerrillas. Despite such violent opposition, a recruiter

at Henderson, an Ohio River town some twenty-ve miles west of Owensboro,

reported enlisting “from forty to sixty men daily.” By mid-September, Adjutant

General Thomas was able to tell the secretary of war that fourteen thousand black

Kentuckians had joined the Army.

11

General Burbridge wanted to mount two of his new black regiments and use

them to hunt guerrillas. He spoke of this to Brig. Gen. Joseph Holt, the judge advo-

cate general, who happened to be in Louisville and sent an enthusiastic telegram to

the secretary of war: “These regiments, composed of men almost raised . . . on horse-

back, of uncompromising loyalty, and having an intimate knowledge of the topog-

raphy of the country, would prove a powerful instrumentality in ridding the state of

those guerrilla bands of robbers and murderers which now infest and oppress almost

every part of it.” After conferring with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, Stanton wrote back

to suggest that mounted infantry might prove a more versatile force than cavalry.

He approved Burbridge’s proposal to mount the troops on horses conscated from

disloyal owners. Despite Stanton’s suggestion, Burbridge went ahead and organized

10

OR, ser. 3, 4: 422 (quotations); Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion

(New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1959 [1908]), pp. 1731, 1733–34, 1738; Berlin et al., Black Military

Experience, pp. 193–96; Howard, Black Liberation in Kentucky, p. 64.

11

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, p. 492; ser. 3, 4: 733. Col L. G. Brown to Capt J. B. Dickson, 23 Jul

1864, 117th United States Colored Infantry (USCI); Lt Col J. H. Hammond to Col W. H. Revere, 30

Aug 1864, and 30 Aug 1864, both in 107th USCI; Capt J. L. Bullis to Maj Gen S. G. Burbridge, 17

Sep 1864 (quotations), 118th USCI; Capt J. C. Cowin to 1st Lt T. J. Neal, 17 Aug 1864, 108th USCI;

all in Entry 57C, Regimental Papers, Record Group (RG) 94, Rcds of the Adjutant General’s Ofce,

National Archives (NA).

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

386

two twelve-company regiments of cavalry, the 5th and 6th United States Colored

Cavalries (USCCs). Adjutant General Thomas saw several companies of the 5th at

Lexington in mid-September. “The men are all selected with reference to weight and

riding qualities,” he told Stanton. “This will make one of the very best regiments in

the service.”

12

Although the 5th USCC was not completely mustered in by late September

1864, it was one of the rst of the new black regiments from Kentucky to go into

action. Earlier that month, some of General Burbridge’s white regiments “utterly

routed and dispersed” an unusually large band of guerrillas, estimated at more than

one hundred fty men, that had recently murdered “a squad of 8 or 10 colored

troops” near Ghent, halfway between Louisville and Cincinnati. With the threat of

irregular warfare somewhat abated, Burbridge turned his attention to a large salt-

works across the state line in southwestern Virginia. Saltville, the closest town, lay

near the tracks of the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad, the only line through

the mountains between Harpers Ferry and Chattanooga. It connected with other

roads that led east to Richmond and carried the saltworks’ product to the Confed-

erate Army of Northern Virginia. When word of this project reached Atlanta, Maj.

Gen. William T. Sherman scoffed, “I doubt the necessity your sending far into

Virginia to destroy the salt works, or any other material interest; we must destroy

their armies.” At that point in the war, Sherman’s Military Division of the Missis-

sippi included all the territory south of the Ohio River between the Appalachians

and the Mississippi River and stood two organizational levels above the District of

Kentucky. Nonetheless, Burbridge continued to plan his attack on Saltville.

13

On 20 September, a division that included nine regiments of Kentucky cavalry

and mounted infantry and one cavalry regiment each from Michigan and Ohio left

Mount Sterling, Kentucky. A four-day march brought it to Prestonburg, some nine-

ty miles to the southeast. There, a mixed force of some six hundred hastily armed

and mounted black recruits joined it. The new troops had just covered more than

one hundred miles from Camp Nelson. Col. James S. Brisbin, commanding ofcer

of the 5th USCC, called these men “a detachment” of his regiment, although an

ofcer of the 6th USCC led them and they included recruits of the 116th USCI as

well. On 27 September, the column continued toward Virginia. Brisbin complained

of the abuse that his men suffered from the overwhelmingly Kentuckian white

troops of the command, “petty outrages, such as . . . stealing their horses, . . . as

well as the jeers and taunts that they would not ght.”

14

As the federal column drew closer to its objective, it met some slight opposi-

tion from a small Confederate cavalry brigade. The troopers of the 5th USCC,

one Confederate wrote, were “the rst [black soldiers] we ever met.” The colonel

commanding the brigade with which the regiment marched mentioned only two

exchanges of shots, although General Burbridge claimed to have fought all the way

12

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 2, pp. 208 (“These regiments”), 231; ser. 3, 4: 733 (“The men”).

13

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 2, pp. 323 (“a squad”), 335, 341, 360 (“utterly routed”), 447 (“I

doubt”); NA Microlm Pub M594, Compiled Rcds Showing Svc of Mil Units in Volunteer Union

Organizations, roll 204, 5th United States Colored Cavalry (USCC).

14

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 553, 556–57 (quotations, pp. 556–57), and pt. 2, p. 436; NA M594,

roll 204, 5th USCC; George S. Burkhardt, Confederate Rage, Yankee Wrath: No Quarter in the

Civil War (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007), p. 194.

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

387

“from the Virginia line up to the salt works.” By 2 October, local militia and rein-

forcements brought by rail had increased the defenders’ numbers to about twenty-

eight hundred, more than half the strength of the attacking force. That morning,

the Union column approached the North Fork of the Holston River. Saltville lay

behind a range of hills on the south bank.

15

Seeing the Confederate position about halfway up the slope, the Union troops

moved forward that morning with the 5th USCC on the extreme left of the line.

The black recruits “behaved well for new troops,” the division commander wrote

afterward. By afternoon, Union attackers had occupied most of the enemy position

but soon found themselves with empty cartridge boxes. General Burbridge did not

explain his failure to provide enough ammunition for this, his pet project. As dark-

ness fell, the federal troopers withdrew as quietly as possible, leaving the saltworks

largely undamaged. They marched all night, putting as much distance as possible

between themselves and the enemy.

16

Just what happened after the battle is hard to determine. “Nearly all the

wounded were brought off, though we had not an ambulance in the command,”

Colonel Brisbin reported. “The negro soldiers preferred present suffering to being

murdered at the hands of a cruel enemy.” The chief medical ofcer, on the other

hand, claimed to be able to give only an estimate of casualties because four of the

surgeons who accompanied the expedition had stayed behind on the eld with the

wounded. What gures he was able to offer showed clearly that the 5th USCC and

the Michigan and Ohio regiments brigaded with it had the hardest ght, suffering

129 killed and wounded, more than two-thirds of the attacking force’s casualties.

Fifty-three men in the 5th USCC constituted more than half the total of missing for

the entire division. This gure probably reected the troops’ inexperience, since

some of those missing found their way back to the regiment later in the war.

17

Confederates certainly murdered some of the wounded they found after the

battle, even invading their own hospitals to do it. Kentucky guerrillas who joined

forces temporarily with the defenders of Saltville committed a number of these

acts; their leader, a notorious gure named Champ Ferguson, shot several wounded

soldiers, black and white, including a Unionist Kentucky ofcer. A spirit of rage

against Unionist Southerners, whom General Forrest called “renegade[s]” and

“Tories,” moved Confederate Kentuckians at Saltville, as it had Forrest’s troopers

at Fort Pillow nearly six months earlier. Viewed by the Confederates as merely

rebellious slaves, black soldiers were an equally inviting target. One of the Union

surgeons who stayed behind with the wounded mentioned that seven black soldiers

were murdered in Confederate hospitals. Left on the eld, other wounded also died,

but their number is uncertain. The day after the ght, a Confederate ofcer noted

in his diary, “Great numbers of them were killed yesterday and today,” although it

is not clear whether he based this remark on hearsay, the sound of indiscriminate

ring after the battle, or personal observation. Another Confederate’s reminiscence

15

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, p. 552 (“from the”); Thomas D. Mays, “The Battle of Saltville,”

in Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era, ed. John David Smith

(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), pp. 200–226 (“the rst,” p. 210).

16

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 552–53, 556 (quotation).

17

Ibid., pp. 553–54, 557 (“Nearly all”); Mays, “Battle of Saltville,” p. 218.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

388

of a wounded trooper nimble enough to dodge, so that it took two shots to kill him,

is at odds with Colonel Brisbin’s insistence that every man who was able to move

by himself accompanied the Union retreat.

18

Saltville was the largest expedition that black troops from Kentucky took

part in west of the Appalachians. From October 1864 to the end of the war,

military activity in the state took the form of constant patrols and infrequent but

sometimes fatal clashes with guerrillas. The two cavalry and four heavy artil-

lery regiments raised in Kentucky did not leave the state; most of the seventeen

infantry regiments did.

19

When Burbridge returned to his headquarters at Lexington on 9 October, he

found Adjutant General Thomas there making arrangements to move some of the

new black regiments to Virginia. At Covington and Louisville, ofcers and men

of these regiments boarded steamboats for travel to one of the West Virginia river

ports, Wheeling or Parkersburg. From there, they moved to Baltimore by rail.

The last leg of the journey was again by water, down the Chesapeake Bay to Fort

Monroe and City Point. Five organizations from Kentucky—the 107th, 109th,

116th, 117th, and 118th USCIs—were in Virginia by the end of the month. The

Union’s ability at this stage of the war to raise ve regiments in as many months

and ship them hundreds of miles to where it meant to use them was a vivid dis-

play of its superiority to the Confederacy in men and machinery. Although black

soldiers in the eld, nationwide, did not number as many as ninety thousand until

January 1865, their presence in the trenches of Virginia, along railroads west of

the Appalachians, and at Mississippi River garrisons was a powerful inuence on

the outcome of the war.

20

The new arrivals found themselves assigned to General Butler’s Army of the

James. Lt. Col. John Pierson of the 109th USCI found this a pleasant change from

Kentucky. “The Colored Troops are as much thought of here by the white soldiers

and ofcers as any men in this Department and treated as well,” he told his daugh-

ter, “and all that I have seen seems glad to see us come and the white Regiments are

anxious to have us Brigaded with them they say the Darkies are Bully fellows to

ght and all the predjudice seems to be gone Ofcers of colored men are as much

thought of as any.” Some old hands in the Army of the James took a more critical

view. “Those . . . new regiments are perfect donkeys,” 2d Lt. Joseph M. Califf of

the 7th USCI wrote in his diary just one day after Pierson addressed his daughter,

“not only with regard to picket [duty] but almost every thing else military.”

21

There can be no doubt that the men of the Kentucky regiments arrived in Vir-

ginia with little grasp of a soldier’s duties; they had few ofcers to instruct them.

General Thomas lled the regiments destined for Virginia with recruits and reas-

18

OR, ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 1, pp. 607 (“renegade[s]”), 610 (“Tories”); vol. 39, pt. 1, p. 554. Mays,

“Battle of Saltville,” pp. 212 (“Great numbers”), 214–16.

19

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 857–58, 876; vol. 45, pt. 1, p. 876; vol. 49, pt. 1, pp. 9, 49. NA

M594, roll 204, 6th USCC; roll 212, 72d USCI; roll 217, 121st USCI.

20

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 3, pp. 157, 200, 219. Monthly mean strength of “Colored Troops in the

United States Army” from The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 2 vols. in 6

(Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1870–1888), vol. 1, pt. 1, pp. 664–65, 684–85, 704–05.

21

J. Pierson to Dear Daugter [sic], 30 Oct 1864, J. Pierson Letters, Clements Library, University

of Michigan, Ann Arbor; J. M. Califf Diary, 31 Oct 1864, Historians les, U.S. Army Center of

Military History (CMH).

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia, 1864–1865

389

signed to them a few ofcers from regiments that were to stay in Kentucky a while

longer. He could do nothing, though, about ofcers who failed, for whatever rea-

son, to report at all. All ve of the ten-company regiments from Kentucky arrived

in Virginia lacking at least one-fourth of the captains and lieutenants that each

required to reach full strength.

22

Maj. Edward W. Bacon joined the 117th USCI in January 1865. Two months

later, he observed “considerable improvement in the command, but much remains

to be done before it reaches even tolerable prociency.” Sickness had reduced the

regiment’s strength to below the minimum number necessary to muster in new of-

cers to drill the men and see to their food, clothing, and shelter. The 118th USCI

needed twenty-one to make up its complement. Absence of instruction and disci-

pline would handicap the Kentucky regiments throughout their service.

23

Lack of ofcers was common, too, in older regiments that had been in the eld

for months. By early fall, Lieutenant Califf himself was one of only eleven ofcers

on duty with his regiment. An ofcer in the 45th USCI wrote at the end of October:

During the last six weeks the company has neither marched nor drilled except a

small squad each day, being the number relieved from guard. At 7 1/2 o’clock

a.m. each day the line is formed for fatigue duty and the men (all except the

sick & a guard) . . . work until 5 o’clock P.M. There are so few ofcers . . . that

each has to take his turn on fatigue about every third day. The amount of labor

required of the command and the lack of ofcers to give the necessary supervi-

sion, has rendered the company less efcient . . . than any well-wisher of our

cause would hope.

24

Ofcers throughout the army were aware of the problem. When Maj. Lewis L.

Weld brought six companies of the 41st USCI from Philadelphia to Virginia in Oc-

tober, he reported to General Butler, who was surprised to learn of the regiment’s

arrival. Butler had requested that ve companies of the 45th USCI, detached at

Washington, D.C., be sent to join their regiment. “You see, Major,” Butler said, “I

didn’t ask for you at all. . . . I suppose your men are perfectly green.” “Perfectly

so, sir,” Weld replied. “Well, I’ll give you a chance to drill,” Butler said. “Send the

major to Deep Bottom,” he told an aide, “with orders to . . . put him on no duty

that can be helped & let him alone till further orders. . . . By the way, Major, teach

your men carefully the loadings & rings.” “Certainly, General, but had I not bet-

ter teach them how to make a right face rst?” “Yes, yes, that is the rst essential,”

Butler agreed, “but don’t forget the other.” Weld took his regiment to Deep Bot-

tom on the James River, a place he knew well from his time as a captain in the 7th

22

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 3, p. 219; Brig Gen L. Thomas to Col P. T. Swaine, 6 Oct 1864, 117th

USCI, and Col O. A. Bartholomew to “Captain,” 3 Nov 1864, 109th USCI, both in Entry 57C, RG

94, NA; Edward A. Miller Jr., The Black Civil War Soldiers of Illinois: The Story of the Twenty-

ninth U.S. Colored Infantry (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998), p. 114.

23

E. W. Bacon to Dear Kate, 9 Mar 1864, E. W. Bacon Papers, American Antiquarian Society

(AAS), Worcester, Mass.; Col A. A. Rand to Capt I. R. Sealy, 24 Oct 1864, 118th USCI, Entry 57C,

RG 94, NA. Bacon was appointed major in the 117th USCI on 5 January 1865; he had been a captain

in the 29th Connecticut and is mentioned in that grade later in this chapter.

24

NA M594, roll 210, 45th USCI; Califf Diary, 17 Oct 1864.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

390

USCI. His divisional commander, Brig. Gen. William Birney, “promise[d] that I

shall not be put into the eld until I have had time to organize & drill somewhat,”

Weld told his mother, “several weeks at least.” Two more companies of the 41st

joined later in the year, but the last two did not arrive until February. Only then was

the regiment up to strength.

25

Butler was not alone in wanting his men prepared for battle. The 127th USCI

also reached Virginia in October and at once took up fatigue duty at Deep Bot-

tom. General Birney, to whose division the regiment belonged, asked for it to be

relieved from this duty and sent to him. “The regiment is new, and the men have

not yet been drilled in the ‘loadings and rings,’” he wrote. “If it is the intention

to have them take an active part in the present campaign, it is absolutely necessary

that opportunity be afforded for drilling and disciplining them. . . . I would prefer

not to put this regiment under re, until the men are taught how to load and re,

and have attained some prociency in drill.” Both the 127th USCI and Weld’s

41st came from Camp William Penn, and the ofcers and men probably had heard

of the disaster that resulted when another untried Philadelphia regiment, the 8th

USCI, went into action at Olustee, Florida, that February.

26

When General Butler told his aide that Weld’s newly arrived troops should be

“put . . . on no duty that can be helped,” he was probably referring to the Dutch

Gap Canal, an excavation that occupied labor details from at least seven black

regiments in the Army of the James during the late summer and fall of 1864. Five

hundred feet long, the canal cut across a neck of land formed by one of the many

bends in the river. Its purpose was to afford passage for U.S. Navy gunboats past

a stretch where the water at low tide was only eight feet deep, half as much as the

draft of the vessels required, and where the re of Confederate batteries could

reach them. Such a canal, Union generals hoped, would also allow them to move

troops more quickly by water than the Confederates could by land.

27

Butler tried to begin his project with a call on 6 August for twelve hundred

volunteers “to do laborious digging[,] to work 7 1/2 hours a day for not more than

twenty days.” Two shifts would labor all the daylight hours. Volunteers would re-

ceive eight cents an hour, an amount that would nearly double a private’s monthly

pay, and an eight-ounce ration of whiskey daily or its cash equivalent. Company

commanders were to read the order to their men at two consecutive daily parades,

25

OR, ser. 1, vol. 42, pt. 2, p. 1044. Lt Col L. Wagner to Maj C. W. Foster, 10 Oct 1864

(W–811–CT–1864); 21 Oct 1864 (W–848–CT–1864); 7 Dec 1864 (W–950–CT–1864); all in Entry

360, Colored Troops Div, Letters Received (LR), RG 94, NA. NA M594, roll 209, 41st USCI; L.

L. Weld to My dearest Mother, 17 Oct 1864 (quotations), L. L. Weld Papers, Yale University, New

Haven, Conn.

26

Brig Gen W. Birney to 1st Lt W. P. Shreve, 8 Oct 1864, Entry 7035, 3d Div, X Corps, Letters

Sent (LS), pt. 2, Polyonymous Successions of Cmds, RG 393, Rcds of U.S. Army Continental Cmds,

NA.

27

OR, ser. 1, vol. 42, pt. 1, p. 657. NA M594, roll 206, 4th and 6th USCIs; roll 208, 22d

USCI; roll 216, 118th USCI; roll 217, 127th USCI. Weld to My dearest Mother, 17 Oct 1864

(quotation); Ofcial Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 30

vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1894–1922), ser. 1, 10: 345 (hereafter cited

as ORN); Dyer, Compendium, pp. 1724, 1727, 1730, 1739; Benjamin F. Butler, Autobiography

and Personal Reminiscences of Major-General Benj. F. Butler (Boston: A. M. Thayer, 1892), pp.

743–44; John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, 30 vols. to date (Carbondale and

Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967– ), 12: 446.