Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Virginia, May–October 1864

361

their way forward. It was “almost impossible to see anything,” the commander of the

right-hand division later testied. By the time the two divisions advanced as far as the

crater, nearby Confederates had recovered from the shock of the explosion and were

ring on their attackers. On the left of the Union advance, General Willcox’s division

occupied about one hundred fty yards of Confederate trench, a task that would have

fallen to a single regiment of one of Ferrero’s brigades if Burnside had been allowed to

carry out his original plan. As matters stood, most of the gap that the explosion left in

the Confederate line was “lled up with troops, all huddled together in the crater itself,

and unable to move under the concentrated re of the enemy, no other troops could be

got in.”

52

Meanwhile, on the Union right, General Potter managed to keep enough control of

his men to organize an attack on Confederates who were ring at his division; but as he

was about to launch it, a message came from Burnside, ordering him to move forward

at once and take the crest. Earlier, one of Ledlie’s heavy artillery regiments had gone

one hundred fty yards in that direction but had to fall back under re from the undam-

aged Confederate lines on either side of the crater. Rather than attack the Confederates

who threatened the Union position, Potter obediently moved his men forward. A few

dozen nearly reached the crest, but found themselves without support and came back.

53

Although most ofcers’ reports did not mention specic times between the ex-

plosion of the mine and the order to withdraw, which arrived about midday, Burnside

probably ordered Potter to advance about 6:00 a.m. or not long afterward. At 5:40,

nearly an hour after the blast, Meade’s chief of staff had sent Burnside a message,

saying that he understood that Ledlie’s men were “halting . . . where the mine ex-

ploded,” and that Burnside should push “all [his] troops . . . forward to the crest at

once.” Again at six, Meade himself ordered Burnside to “push your men forward at

all hazards (white and black) and don’t lose time . . . but rush for the crest.” Meade’s

insistence on frequent information became so great that at 7:30 he asked, “Do you

mean to say your ofcers and men will not obey your orders to advance? . . . I wish to

know the truth and desire an immediate answer.” Burnside replied about ve minutes

later that it was “very hard to advance to the crest. I have never in any report said

anything different from what I conceived to be the truth. Were it not insubordinate I

would say that the latter remark of your note was unofcerlike and ungentlemanly.”

54

By the time the generals began to quarrel, Ferrero’s division of the IX Corps

had been waiting for hours for the word to advance. The night before, the men of

the 19th USCI “laid down after making all needful preparations,” Captain Rickard

wrote the next day. They expected to move toward the front trenches well before

dawn, he continued, “but did not till sunrise when I was aroused from my slumbers

by the most terrible cannonading I have ever heard.” The division approached the

old front line in time to receive an order from Burnside to advance, bypass the

crater, and capture the crest beyond it. Ferrero did not like what he had been able

to learn about the confusion ahead and protested that troops in front of his were

52

Report of the Joint Committee, 2: 78 (“lled up”), 87 (“almost impossible”). On the weather,

see Krick, Civil War Weather, pp. 133–34; Fleetwood Diary, esp. 24 Jul 1864; Army and Navy

Journal, 6 August 1864.

53

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 541, 547–48, 554.

54

Ibid., pp. 140 (“halting . . . where”), 141 (“push your”), 142 (“Do you mean”), 143 (“very hard”).

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

362

blocking the way. His division, just behind the second brigade of Willcox’s, halted

close by Surgeon Smith’s aid station. Smith later testied that it took three orders

from Burnside to set Ferrero’s troops in motion. Having sent his division forward,

Ferrero lingered near the aid station with General Ledlie. “I deemed it more neces-

sary that I should see that they all went in than that I should go in myself,” he told

the court of inquiry.

55

Not until after 8:00 a.m. were Ferrero’s two brigades able at last to move into the

open. Col. Henry G. Thomas’ report said that the delay lasted half an hour, although

he later testied that it was an hour and a half. Emerging from the Union trenches,

Thomas’ brigade, some twenty-four hundred men of the 19th, 23d, 28th, 29th, and

31st USCIs, headed left; that of Col. Joshua K. Sigfried, made up of the 27th, 30th,

39th, and 43d, about two thousand strong, went right. The 23d and 43d had completed

organization only the month before; the 28th, 29th, and 31st went into battle with only

six companies each, all that their recruiters had been able to ll so far. As the men

attempted to pass the crater, the same daunting disorder faced each brigade. Colonel

Sigfried saw “living, wounded, dead, and dying crowded so thickly that it was very dif-

cult to make a passage way through.” Captain Rickard and the 19th USCI

advanced double quick over the breast works exposed to a galling re & made towards

the [crater.] I never expected to reach it men were falling all around me but I was not

touched. Got into the Crater caused by the explosion & an awful sight it was lled

55

Ibid., pp. 93 (quotation), 102–04, 118–19; Report of the Joint Committee, pp. 108–09; J. H.

Rickard to Dear Sister, 31 Jul 1864, Rickard Letters.

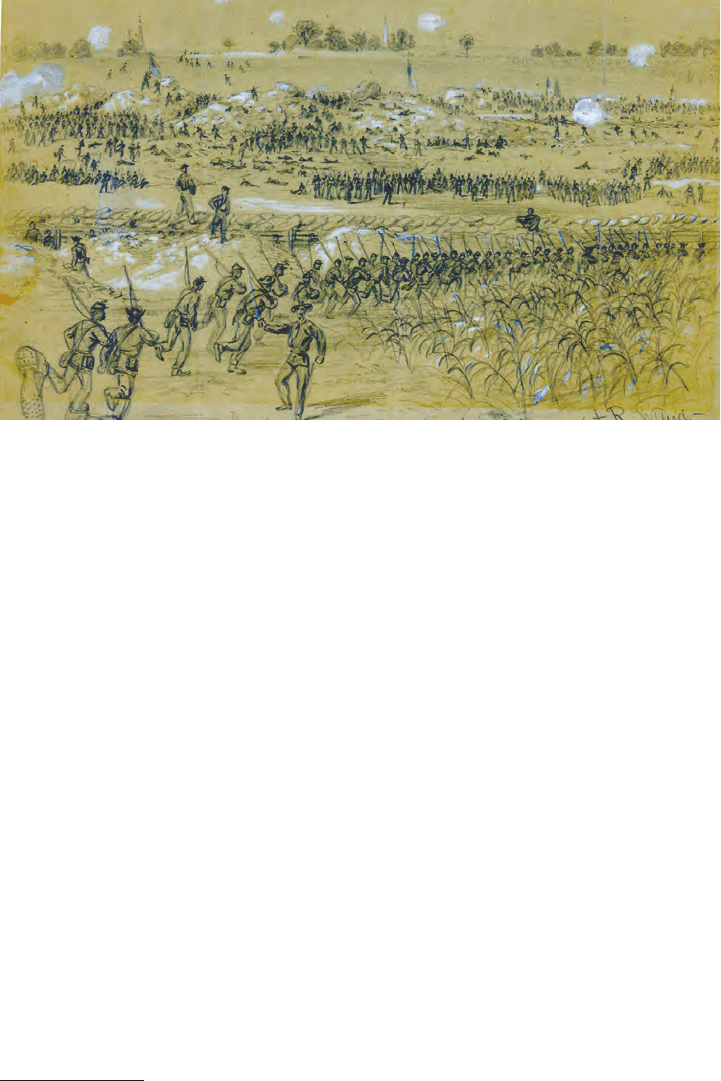

Alfred R. Waud captured the confusion that prevailed among the Union attackers by the

time the black soldiers of the IX Corps (in the foreground) joined the battle.

Virginia, May–October 1864

363

with dead rebels dead union soldiers white & black wounded too of every description

& soldiers both white & black clambering through . . . over the shrieking wounded.

One staff ofcer in Sigfried’s brigade claimed that only Colonel Bates’ 30th USCI

maintained a semblance of order on its way forward through the crater.

56

This disorganization began to tell when ofcers tried to assemble their

troops for an attack on the crest, which still remained in Confederate hands.

Afterward, Ferrero told investigators that his men “went in without hesitation,

moved right straight forward, passed through the crater that was lled with

troops, and all but one regiment of my division passed beyond the crater.” Two

questions later, though, he had to admit that he was not present, but “at no time

[was] farther [away] than eighty or ninety yards.” If he remained in or behind

the Union front trench, from which his men attacked, he would have been at

least one hundred fty yards from the crater, for the miners’ tunnel was more

than ve hundred ten feet long. Ferrero’s remarks also contradict the testimony

of the ofcer who had been in the crater and claimed that only the 30th USCI

moved through it without much confusion.

57

The brigade commanders told a grimmer story. Brig. Gen. John F. Har-

tranft of Willcox’s division said that Ferrero’s men “passed to the front just

as well as any troops; but they were certainly not in very good condition . . . ,

because in passing through the crater they got confused; their regimental and

company organization was completely gone.” In Sigfried’s brigade, the only

regiment that managed to close with the enemy was the 43d USCI, which took

one Confederate battle ag from the enemy and recaptured colors that had been

lost earlier in the day by a white regiment of the IX Corps. Sigfried recorded

that the 43d returned with “a number” of prisoners, despite the men’s earlier

vows to “Remember Fort Pillow!” On the left, Thomas tried to order a charge,

but the 31st USCI had just lost its three ranking ofcers and only about fty of

the men responded: “the re was so hot that half the few [men] who came out

of the works were shot,” he reported. Thomas then spent some time trying to

separate men of the 28th and 29th USCIs from the armed mob in the crater and

form them into a coherent body. Just as he was about to accomplish this, he re-

ceived a message from Ferrero, whom he had not seen since leaving the Union

front trench: “Colonels Sigfried and Thomas . . . : If you have not already done

so, you will immediately proceed to take the crest in your front.” Accordingly,

some one hundred fty or two hundred men of the 23d, 28th, and 29th USCIs

moved forward about fty yards until they met “a heavy charging column of

the enemy” of perhaps twice their strength “and after a struggle [were] driven

back over our rie pits. At this moment a panic commenced,” Thomas report-

ed. “The black and white troops came pouring back together.” Many of them

crowded into the crater. Sigfried’s brigade held on “until pushed back by the

56

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 105, 586, 590, 596 (“living, wounded”), 598; Rickard to Dear

Sister, 31 Jul 1864. Brigade strengths based on gures for IX Corps, 30 June and 31 July 1864, in

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 2, p. 542, and pt. 3, p. 78; Field Return, 20 Jun 1864, and Casualty List, 30 Jul

1864, both in Entry 5122, 4th Div, IX Corps, LS, pt. 2, RG 393, NA.

57

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, p. 93.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

364

mass of troops, black and white, who rushed back upon it, . . . until the en-

emy occupied the works to its left and the opposite side of the intrenchments,

when, becoming exposed to a terric ank re, losing in numbers rapidly and

in danger of being cut off, [the brigade] fell back behind the line . . . where it

originally started from.”

58

That left hundreds of men still in the crater. These included about one

hundred ofcers and men of the 19th USCI, still a disciplined force, who strug-

gled into the crater, Thomas said, “and remained there for hours, expending all

their own ammunition and all they could take from the cartridge boxes of the

wounded and dead men that lay thick together in the bottom of this pit.” Capt.

Theodore Gregg, commanding one of the veteran regiments in Potter’s divi-

sion, was present for the aftermath of Thomas’ unsuccessful charge. “A major

of one of the negro regiments placed his colors on the crest of the crater, and

the negro troops opened a heavy re on the rebels,” he reported.

In a few moments, the rebel force . . . dashed into the pits among us, where a

desperate hand-to-hand conict ensued, both parties using their bayonets and

clubbing their muskets. . . . During this brief contest the negroes in the crater

kept up a heavy re of musketry on the advancing enemy, compelling them to

take shelter. Many of our men being killed and wounded, and the enemy press-

ing us hard, we were compelled to fall back into the crater in order to save our

little band, while the negroes kept up a heavy re on the rebels outside. . . .

[Brig. Gen. William F.] Bartlett and one of his aides-de-camp . . . did every-

thing in their power to rally the troops on inside the crater, but found it to be

impossible, as the men were completely worn out and famished for water. He

succeeded in rallying some twenty-ve or thirty negroes, who behaved nobly,

keeping up a continual re. . . . The suffering for want of water was terrible.

Many of the negroes volunteered to go for water with their canteens. A great

part of them were shot in the head while attempting to get over the works; a few,

more fortunate than others, succeeded in running the gauntlet and returned with

water to the great relief of their suffering comrades.

As occurred throughout the IX Corps that day, the behavior of the men in Fer-

rero’s division varied from panicked to heroic.

59

Meade heard from an ofcer in a signal tower that two brigades of infantry

were on their way to reinforce the Confederate defenders and sent a message

at 9:30 to tell Burnside to withdraw the troops if he thought they could accom-

plish nothing more. Fifteen minutes later, the suggestion became an order, al-

though Meade left it to Burnside’s discretion whether to begin the withdrawal

at once or wait till dark. General Bartlett of Ledlie’s division replied at 12:40

p.m. from the crater, where he was the ranking ofcer: “It will be impossible

to withdraw these men, who are a rabble without ofcers, before dark, and

not even then in good order.” Most of the men on the spot did not take time to

58

Ibid., pp. 102 (“passed to”), 105 (“Colonels Sigfried”), 106–07, 596 (“a number”), 597 (“until

pushed”), 598 (“the re,” “a heavy”), 599 (“and after”).

59

Ibid., pp. 554–55 (“A major”), 599 (“and remained”).

Virginia, May–October 1864

365

consult their watches frequently, but Captain Gregg noted that it was 2:00 p.m.

when he left the crater to rejoin the hundred men of his regiment who had been

left behind some nine hours earlier to provide covering re for the advance.

Not long after that, Confederates swept into the crater, killing or capturing all

the Union soldiers who remained.

60

Casualties, as always, were hard to determine exactly. Ferrero’s division

suffered some thirteen hundred, about 38 percent of the thirty-ve hundred ca-

sualties in the IX Corps that day. Almost one-third of the black casualties were

dead, some of them under conditions similar to the killing of wounded and

surrendered men at Fort Pillow nearly four months earlier. The difference this

time was that three Confederate soldiers from different regiments, in private

letters written days after the battle, mentioned the men of Ferrero’s division

shouting “No quarter!” and “Remember Fort Pillow!” The war was becoming

as bloodthirsty as Lieutenant Verplanck had feared that spring. Still, Confeder-

ate deserters two days after the battle told Union ofcers that they had seen two

hundred or two hundred fty black prisoners of war at work for the Confeder-

ates, cleaning up the battleeld and unearthing for proper burial corpses that

had been buried by the explosion of the mine. In October, Confederate authori-

60

Ibid., p. 556, and pt. 3, pp. 661–64 (quotation, p. 663).

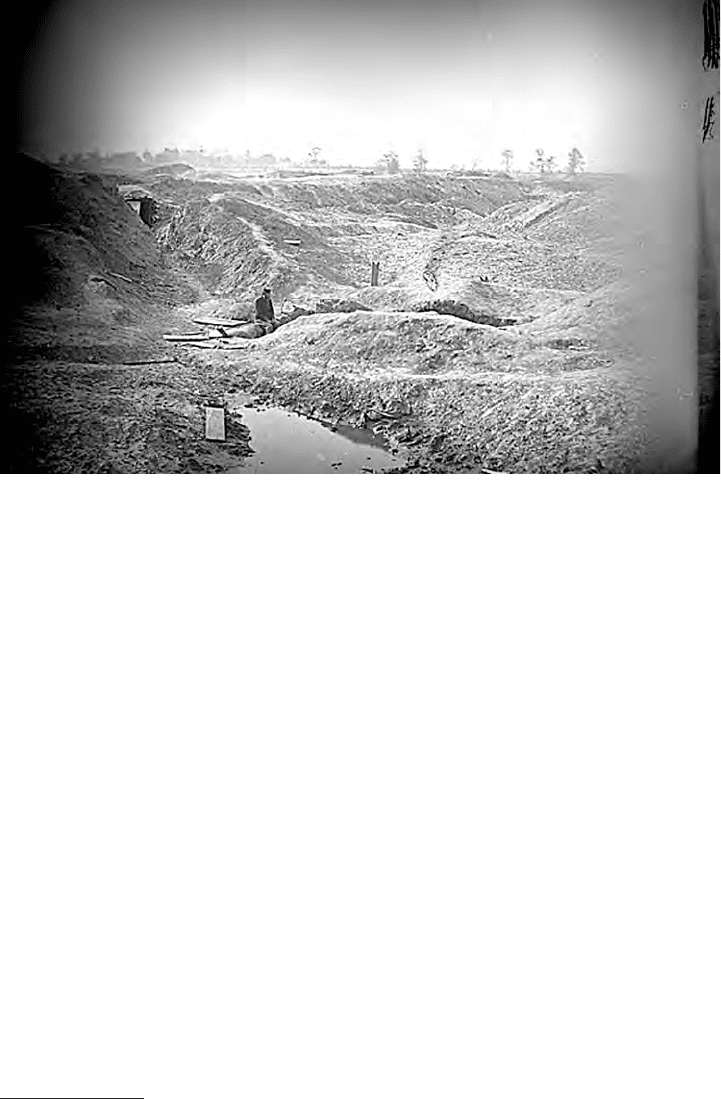

The crater, not long after Union troops entered Petersburg in April 1865

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

366

ties in Richmond reported that a total of 216 black Union soldiers had passed

through the city’s prisons.

61

Three days after the attack, Grant asked that the War Department appoint a court

of inquiry “to examine into and report upon the facts and circumstances attending”

the operation. The court sat for seventeen days between 8 August and 8 September.

Maj. Gen. Wineld S. Hancock, commander of the II Corps; two divisional com-

manders in the Army of the Potomac; and the inspector general of the Army ques-

tioned thirty-two witnesses ranging in rank from Grant himself to 1st Lt. Albert A.

Shedd of the 43d USCI, a staff ofcer who had been present in the crater.

62

The generals at once began to prepare their excuses for the catastrophe. Meade,

in a sworn statement contradicted by routine messages he had sent to two corps

commanders weeks earlier, tried to justify his substitution of one of Burnside’s

white divisions for Ferrero’s to lead the attack. “Not that I had any reason to doubt

. . . the good qualities of the colored troops, but that . . . he should assault with his

best troops; not that I had any intention to insinuate that the colored troops were in-

ferior to his best troops, but that I understood that they had never been under re.”

Burnside referred to Ferrero’s division when he said “no raw troops could have

been expected to have behaved better,” but the remark certainly applied to many

other regiments in his corps as well. Ferrero told the court of inquiry that his men

were “raw, new troops, and had never been drilled two weeks from the day they

entered the service to that day.” Although Ferrero had not been close enough to

the battle to affect the result, he knew what training his men had and his statement

seems to agree with the unofcial remarks of Captain Rogall and Sergeant Mc-

Coslin. Reports of the colonels who led brigades, and who actually spent time with

the troops on 30 July, refer to “disorganized,” “more or less broken” troops retiring

in “confusion.” Senior ofcers exerted so little control that day that it was easy for

them, in their reports, to blame any troops other than their own for panicking and

running. This was especially so for the divisional commanders. Colonel Thomas

had seen Ferrero, Ledlie, and Willcox at the surgeons’ station as he led his brigade

forward that morning, which meant that Potter alone of the four generals had been

close enough to see the ghting.

63

The court found that most of the reasons for the failure fell under the heading

of improper leadership, whether in preparation of the troops, in prompt execution

of the plan, or in direct supervision at the scene of the operation. In its opinion,

the court declared that Burnside, Ferrero, Ledlie, Willcox, and one brigade com-

mander who had also been absent were “answerable” for the failure, although it

absolved them of “any disinclination . . . to heartily co-operate in the attack.” Only

Burnside, who was relieved of his command two weeks after the battle, suffered

61

Ibid., p. 248, gives a gure of 209 killed among 1,327 casualties in Ferrero’s division and

3,475 casualties for the entire IX Corps. Bryce A. Suderow, “The Battle of the Crater: The Civil

War’s Worst Massacre,” Civil War History 43 (1997): 219–24, revises the gure to 423 killed among

1,269 casualties in the division and also quotes the Confederate letters. For Lieutenant Verplanck,

see above, note 10. The Confederate deserters’ report is in OR, ser. 1, vol. 42, pt. 2, p. 5. Confederate

authorities’ report is in ser. 2, vol. 7, pp. 987–88.

62

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, p. 18 (“to examine”).

63

Ibid., pp. 46 (“Not that”), 93 (“raw, new”), 528 (“no raw”), 538 (“disorganized”), 542

(“confusion”), 567, 579 (“more or less”).

Virginia, May–October 1864

367

any adverse consequences for the defeat. Meade remained at the head of the Army

of the Potomac, which he led until the end of the war; Ledlie resigned in January

1865; Ferrero, Potter, and Willcox all received the brevet rank of major general at

different times for their roles in the Overland Campaign and the siege. Potter’s and

Willcox’s brevets were dated 1 August and had been in the works long before the

failed attack; that Ferrero’s did not come until December suggests that Grant still

retained some condence in his abilities.

64

Yet another investigation remained, called for by Congress and conducted

by the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Radical Republicans had

founded the committee in the fall of 1861 in response to early Union reversals.

Four months after the Petersburg mine disaster, committee members traveled by

boat from Washington to the Union base at City Point to gather testimony. A large

part of their nal report consisted of reprinting the proceedings of the Army’s

own court of inquiry, but the committee’s conclusion held General Meade alone

responsible for “the disastrous result.” Republicans had been nding fault with

Meade ever since his failure, as they saw it, to launch a vigorous pursuit of

the retreating Confederate army after the battle of Gettysburg. The committee’s

conclusion was to be expected but, as with the earlier court of inquiry, it had no

practical result.

65

No one canvassed the opinions of General Hinks’ ofcers and men about

what their less-experienced comrades in Ferrero’s division had done. Sergeant

Major Fleetwood expressed disgust in his usual terse way: “Col[ore]d Div of 9th

Corps charged or attempted [to,] broke and run!” In the 5th USCI, Lieutenant

Grabill dismissed the entire operation as “a splendid zzle.” Colonel Shurtleff

worried “that the blame will be laid upon the colored division of Burnside’s

corps. The truth is that the hardest part of the programme was assigned to them

though they are comparatively inexperienced, many of them never before under

re. They went farther to the front than any white troops and were not routed

until one brigade of white troops had rst been driven back in panic.” Members

of Hinks’ divisional staff were well informed, or claimed to be; Captain Carter

knew that the mine contained four tons of powder, and Lieutenant Verplanck

blamed the 112th New York specically for causing the panic. Verplanck went

on: “I saw many cases of bad management or rather want of interest on the part

of division commanders in the 9th Corps. I know not if [it] was cowardice but

they were not to be seen in the front where their brigades were ghting. . . . I

believe faithfully that if corps & division commanders . . . had done their duty

that day we would have gained a great victory.” Disappointment in the result of

the operation mingled with dread that the failure would cast all black soldiers in

a bad light. Lieutenant Grabill wrote: “The selection of troops for the most dif-

cult part was most blunderous. Ferrero’s Colored Division, undisciplined, raw

and unused to ghting were chosen to accomplish what should be expected only

64

Ibid., p. 129 (quotation). The entire record of the court is on pp. 42–163. Generals’ records

in Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army, 2 vols.

(Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1903), 1: 417, 622, 802, 1038.

65

Report of the Joint Committee, 2: 11 (quotation); Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder: The

Committee on the Conduct of the War (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998), pp. 18–19, 24,

187–92.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

368

of the best of veterans. . . . Of course the Copperhead press will now make a great

blow about ‘nigger troops’ in the Abolition War.”

66

After a four-hour truce on the morning of 1 August to allow Union troops to

bury their dead and remove their wounded, who had lain in the open for two nights

and a day, the siege resumed its routine. In the 5th USCI, Lieutenant Grabill called

it “easier times than we used to have. Now we are in the trenches but about half

the time and our fatigue work is not so great as it used to be.” He noted that the

Confederates no longer tended to waste their ammunition, but that with the enemy

lines “in plain sight . . . two or three hundred yards in our front,” movement in the

open was dangerous.

67

Sniper re presented a threat throughout the day. Men in the trenches saw

sharpshooters “loang about,” as one ofcer put it, with special sights on their

ries, “peeping through the loop holes & watching for a shot.” One of them ap-

66

S. A. Carter to My own darling Emily, 31 Jul 1864; Fleetwood Diary, 30 Jul 1864; E. F.

Grabill to My Own Loved One, 1 Aug 1864, Grabill Papers; G. W. Shurtleff to My darling Girl, 1

Aug 1864, Shurtleff Papers; R. N. Verplanck to Dear Mother, 1 Aug 1864, Verplanck Letters.

67

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 3, p. 821; E. F. Grabill to My own dear Anna, 12 Aug 1864, Grabill Papers.

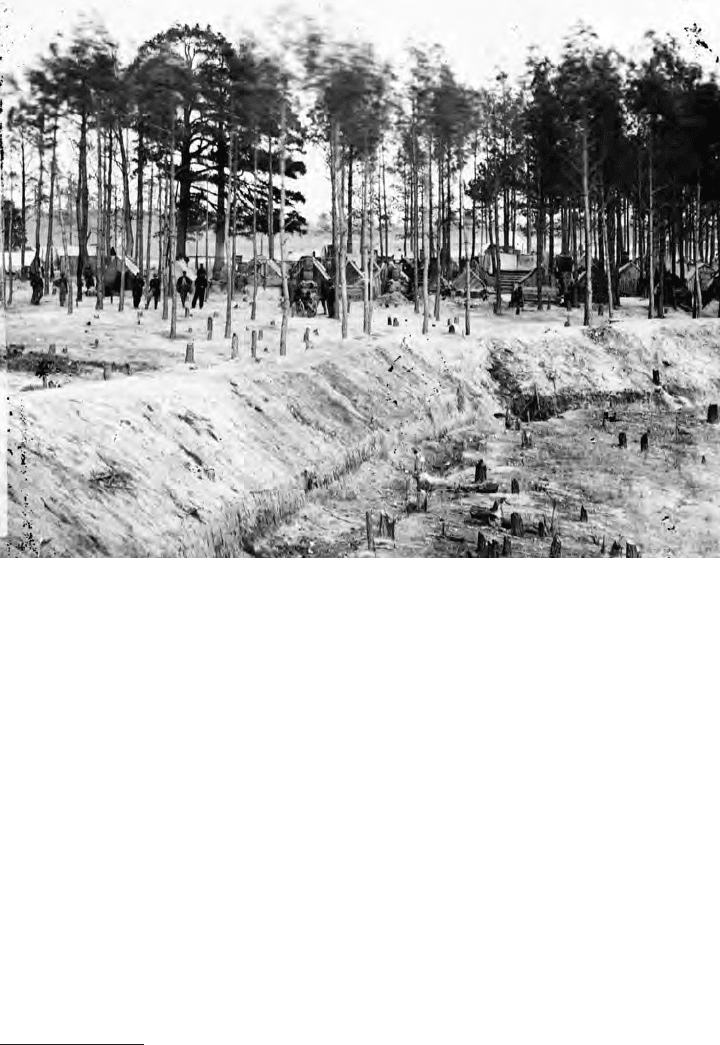

Behind the trenches, trees supplied both shelter and rewood. Stumps surround the camp

of a black regiment from Ohio—either the 5th U.S. Colored Infantry or the 27th—during

the siege of Petersburg.

Virginia, May–October 1864

369

proached the ofcer “with a careless lounging gait” and asked, “Isn’t there a cuss

with a black hat over here who bothers you a good deal?” “Yes he killed one of my

men this morning,” the ofcer replied. “Well said the sharpshooter I’ll watch for

him. He laid himself down by the loop hole & in ten minutes,” the ofcer wrote, “I

saw him slowly lift up[,] sight across his rie & re we were not troubled any more

by the man with the black hat. . . . I get four or ve good shots most every day he

said as he lounged away.”

68

Not far away, Assistant Surgeon Merrill of the 22d USCI found himself in a

relatively quiet part of the line. “There is nothing stirring here,” he wrote. “We have

a tacit truce on our front—neither party disturbs the other.” From a hill behind the

Union position, Merrill had “a fair view of the rebel lines for a mile or more . . .

and we . . . can see both sides enjoying themselves during the day time. . . . There

is a melon patch between them, it is said, and both parties visit it at night. Water

melons are one of the greatest luxuries we have here now.”

69

Other men besides melon hunters crossed from one side to the other. De-

sertion plagued the Army of Northern Virginia after three months of continual

ghting, a period of action that had no parallel in the war. Some dispirited Con-

federates merely turned toward home; others headed for the trenches opposite,

where Union ofcers interrogated them and, if they took an oath and were will-

ing to perform civilian work for the North, sent them to Washington, D.C., or

even as far as Philadelphia. By mid-August, General Lee thought the problem

so grave that he mentioned it to the Confederate secretary of war. During the

two weeks before Lee wrote to the secretary, at least sixty-ve of his soldiers

crossed to the Union lines. “Deserters came in on our Picket line the last two

nights,” wrote Capt. Edward W. Bacon of the 29th Connecticut (Colored), “&

were quite terried when they found they had thrown themselves into the hands

of the avenging negro.”

70

Union ofcers learned from these deserters that Lee had dispersed his army

somewhat, detaching at least two divisions for service elsewhere while the rest

held the trenches. Seeing an opportunity, Grant decided to send the II and X

Corps to threaten Richmond. This would, he thought, cause Lee to withdraw

troops either from the Shenandoah Valley or the trenches south of the James

River to strengthen the defenses of the Confederate capital. A decision to draw

reinforcements from south of the James, Grant told Meade, might “lead to al-

most the entire abandonment of Petersburg.”

71

The twelve thousand ofcers and men of General Hancock’s II Corps took

two days to withdraw from the trenches around Petersburg, board transport

vessels at City Point, and disembark at Deep Bottom, on the north bank of the

James. Maj. Gen. David B. Birney postponed the advance of his X Corps, a

68

L. L. Weld to My dearest Mother, 29 Aug 1864, L. L. Weld Papers, YU.

69

C. G. G. Merrill to Dear Father, 21 Aug 1864 (“There is”) and C. G. G. Merrill [no salutation],

28 Aug 1864 (“a fair view”), both in Merrill Papers.

70

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 3, p. 693; vol. 42, pt. 2, pp. 4–5, 17, 28, 40–42, 53–54, 66, 76, 78, 84–85,

96–97, 103, 113–15, 125–28, 141–42, 1175–76. E. W. Bacon to Dear Kate, 26 Sep 1864, E. W. Bacon

Papers, AAS; J. Tracy Power, Lee’s Miserables: Life in the Army of Northern Virginia from the

Wilderness to Appomattox (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), pp. 128, 182–83.

71

OR, ser. 1, vol. 42, pt. 2, pp. 112, 114–15, 123, 136, 141 (quotation), 167.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

370

force nearly as large as Hancock’s, to wait for the new arrivals. The sun had

been up for hours on 14 August by the time the troops of the II Corps all got

ashore. Six days of inconclusive ghting followed, with the Union army failing

to gain the advantage it sought.

72

A recent addition to the X Corps was a brigade of black regiments withdrawn

from the Department of the South and led by the corps commander’s older broth-

er, Brig. Gen. William Birney. The 7th, 8th, and 9th USCIs, along with the 29th

Connecticut (Colored), had arrived at Deep Bottom on 13 August. These regi-

ments would be the nucleus of an all-black division like those that were already

serving in the IX and XVIII Corps. During the next few days, the brigade took

part in an advance and repelled a Confederate counterattack. The 7th USCI “saw

very little ghting” the morning after its arrival, Capt. Lewis L. Weld wrote:

We were kept in reserve . . . & lay in the wood seeing the dead & wounded

brought back through our lines. . . . About 3 [p.m.] or perhaps a little later the

7th was ordered to charge and take a line of Rebel rie pits. . . . We formed in

line of battle & moved across the open corn eld in our front . . . , charged the

works with a yell & took them in splendid style, so those who saw it say. My

company is the extreme left company of the line & I was too busy to see much

beside the work before me. The re was very hot. . . . The Regt however did

itself great credit both ofcers & men.

The next day, the brigade “did nothing but march & lie still waiting for

developments.” On 16 August, an “all day ght” was “very wearisome but our

Regt was at no time under very severe re. . . . About noon we were moved over

on the right to charge a line of works there but after we had arrived we found

the charge already made but partially unsuccessful[;] the lines had been taken

but had to be abandoned. We lay nearly all night in a dense wood, all the latter

part of the afternoon & early evening being under a re not severe but annoying

& not being able to return it.”

73

Skirmishers on both sides continued to exchange shots the next day. “Every

few minutes,” Weld wrote, “a bullet comes whistling over our heads.” During

ve days’ ghting, Birney’s brigade lost 136 ofcers and men killed, wounded,

and missing. Such casualties must have seemed light to those men of the 8th

USCI who had survived the defeat at Olustee in February, when the loss of

their regiment alone amounted to 343 killed, wounded, and missing. After a

failed Confederate attack on 18 August, Birney reported to Hancock: “The

colored troops behaved handsomely and are in ne spirits.”

74

The mid-August operation of Birney’s brigade was the rst to be covered

by another new arrival along the James, the reporter Thomas M. Chester. His

employer, the Philadelphia Press, had overcome enough of its past indiffer-

72

Ibid., pt. 1, pp. 39, 119–20, 216, 249, 677.

73

NA M594, roll 206, 7th, 8th, and 9th USCIs; roll 208, 29th Conn. L. L. Weld to My dearest

Mother, 17 Aug 1864, Weld Papers.

74

OR, ser. 1, vol. 35, pt. 1, p. 312; vol. 42, pt. 1, pp. 120, 219, 678 (quotation), 779–80. Weld to

My dearest Mother, 17 Aug 1864.